Molecular Testing in Organ Biopsies and Perfusion Fluid Samples from Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Positive Donors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

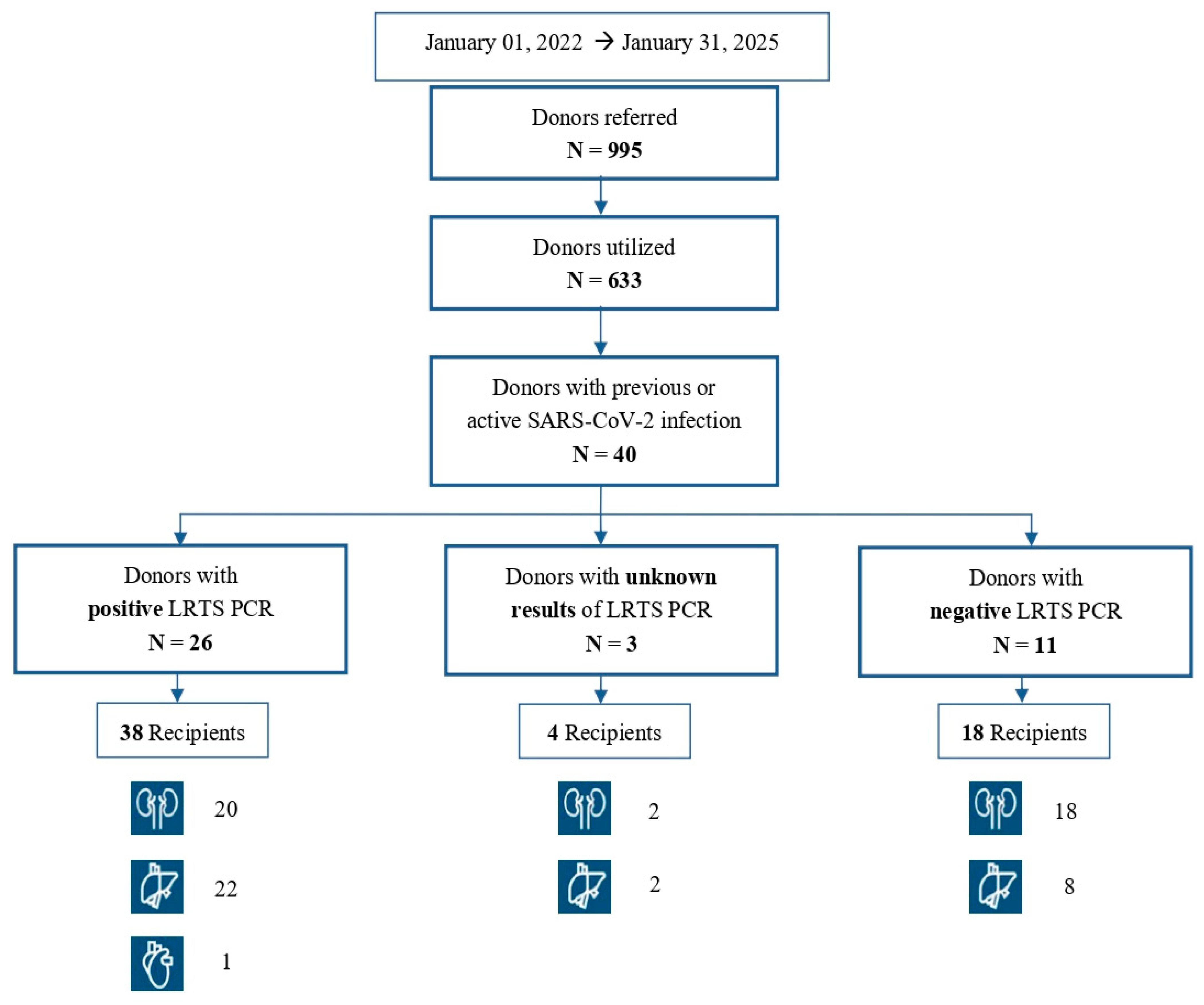

3.1. Donors

3.2. Recipients

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE2 | angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 |

| BAL | bronchoalveolar lavage |

| BAS | bronchoaspirate |

| CNT | National Transplant Centre (of Italy) |

| COVID-19 | coronavirus disease 2019 |

| Ct | cycle threshold |

| DBD | donation after brain death |

| DCD | donation after cardiac death |

| LRT | lower respiratory tract |

| NPS | nasopharyngeal swab |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| RBD | receptor-binding domain |

| RdRp | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase |

| SARS-CoV-2 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| sgRNAs | subgenomic RNAs |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19. 11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/transcripts/who-audio-emergencies-coronavirus-press-conference-full-and-final-11mar2020.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Gaussen, A.; Hornby, L.; Rockl, G.; O’Brien, S.; Delage, G.; Sapir-Pichhadze, R.; Drews, S.J.; Weiss, M.J.; Lewin, A. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Cells, Tissues, and Organs and the Risk of Transmission Through Transplantation. Transplantation 2021, 105, 1405–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Supply of Substances of Human Origin in the EU/EEA—First Update. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/COVID%2019-supply-substances-human-origin-first-update.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Kaul, D.R.; Valesano, A.L.; Petrie, J.G.; Sagana, R.; Lyu, D.; Lin, J.; Stoneman, E.; Smith, L.M.; Lephart, P.; Lauring, A.S. Donor to recipient transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by lung transplantation despite negative donor upper respiratory tract testing. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 2885–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.; Humar, A.; Keshavjee, S.; Cypel, M. A call to routinely test lower respiratory tract samples for SARS-CoV-2 in lung donors. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 2623–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, P.A.; Lombardini, L.; Donadio, R.; Peritore, D.; Feltrin, G. Perspective on donor-derived infections in Italy. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2024, 26 (Suppl. 1), e14398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peghin, M.; Grossi, P.A. COVID-19 positive donor for solid organ transplantation. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centro Nazionale Trapianti (CNT). Available online: https://www.trapianti.salute.gov.it/it/cnt-avviso/aggiornamento-delle-misure-di-prevenzione-della-trasmissione-dellinfezione-da-nuovo-12/ (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Romagnoli, R.; Gruttadauria, S.; Tisone, G.; Maria Ettorre, G.; De Carlis, L.; Martini, S.; Tandoi, F.; Trapani, S.; Saracco, M.; Luca, A.; et al. Liver transplantation from active COVID-19 donors: A lifesaving opportunity worth grasping? Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 3919–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taffertshofer, K.; Walter, M.; Mackeben, P.; Kraemer, J.; Potapov, S.; Jochum, S. Design and performance characteristics of the Elecsys anti-SARS-CoV-2 S assay. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1002576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, P.A.; Wolfe, C.; Peghin, M. Non-Standard Risk Donors and Risk of Donor-Derived Infections: From Evaluation to Therapeutic Management. Transpl. Int. 2024, 37, 12803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kute, V.B.; Fleetwood, V.A.; Meshram, H.S.; Guenette, A.; Lentine, K.L. Use of Organs from SARS-CoV-2 Infected Donors: Is It Safe? A Contemporary Review. Curr. Transplant. Rep. 2021, 8, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azhar, A.; Kleiboeker, S.; Khorsandi, S.; Duncan Kilpatrick, M.; Khan, A.; Gungor, A.; Molnar, M.Z.; Morales, M.; Levy, M.M.; Kamal, L.; et al. Detection of Transmissible Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 from Deceased Kidney Donors: Implications for Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2023, 107, e65–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infectious Disease Society of America; Association for Molecular Pathology. IDSA and AMP Joint Statement on the Use of SARS-CoV-2 PCR Cycle Threshold (Ct) Values for Clinical Decision-Making. Available online: https://www.idsociety.org/globalassets/idsa/public-health/covid-19/idsa-amp-statement.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Santos Bravo, M.; Berengua, C.; Marín, P.; Esteban, M.; Rodriguez, C.; del Cuerpo, M.; Miró, E.; Cuesta, G.; Mosquera, M.; Sánchez-Palomino, S.; et al. Viral Culture Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Subgenomic RNA Value as a Good Surrogate Marker of Infectivity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022, 60, e0160921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saharia, K.K.; Ramelli, S.C.; Stein, S.R.; Roder, A.E.; Kreitman, A.; Banakis, S.; Chung, J.-Y.; Burbelo, P.D.; Singh, M.; Reed, R.M.; et al. Successful lung transplantation using an allograft from a COVID-19-recovered donor: A potential role for subgenomic RNA to guide organ utilization. Am. J. Transplant. 2023, 23, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, S.; Saracco, M.; Cocchis, D.; Pittaluga, F.; Lavezzo, B.; Barisone, F.; Chiusa, L.; Amoroso, A.; Cardillo, M.; Grossi, P.A.; et al. Favorable experience of transplant strategy including liver grafts from COVID-19 donors: One-year follow-up results. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2023, 25, e14126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jashari, R.; Van Esbroeck, M.; Vanhaebost, J.; Micalessi, I.; Kerschen, A.; Mastrobuoni, S. The risk of transmission of the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) with human heart valve transplantation: Evaluation of cardio-vascular tissues from two consecutive heart donors with asymptomatic COVID-19. Cell Tissue Bank. 2021, 22, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitrock, J.N.; Carter, M.M.; Price, A.D.; Delman, A.M.; Pratt, C.G.; Wang, J.; Sharma, D.; Quillin, R.C.; Shah, S.A. Novel Study of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in Post-Reperfusion Liver Biopsies after Transplantation Using COVID-19-Positive Donor Allografts. Transplantology 2024, 5, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmo, A.; Gardiner, D.; Ushiro-Lumb, I.; Ravanan, R.; Forsythe, J.L.R. The Global Impact of COVID-19 on Solid Organ Transplantation: Two Years Into a Pandemic. Transplantation 2022, 106, 1312–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peghin, M.; Graziano, E.; De Martino, M.; Balsamo, M.L.; Isola, M.; López-Fraga, M.; Cardillo, M.; Feltrin, G.; González, B.D.-G.; Grossi, P.A.; et al. Acceptance of Organs from Deceased Donors with Resolved or Active SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Survey from the Council of Europe. Transpl. Int. 2024, 37, 13705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic. WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Supply of Substances of Human Origin in the EU/EEA—Third Update. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Supply-SoHO-COVID-19-third-update-august2023.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

| DONORS (N = 40) | |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (min–max) | 63 (20–85) |

| Male sex [n (%)] | 27 (67.5%) |

| Type of donor [n (%)] | |

| DBD | 32 (80%) |

| DCD | 8 (20%) |

| Cause of death [n (%)] | |

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 21 (52.5%) |

| Stroke/Post-anoxicencephalopathy | 11 (27.5%) |

| Polytrauma/Head Trauma | 7 (17.5%) |

| Hypoglycemic coma | 1 (2.5%) |

| LRTS SARS-CoV-2 PCR at organ procurement [n (%)] | |

| Positive | 26 (65%) |

| Negative | 11 (27.5%) |

| Not available | 3 (7.5%) |

| Cycle threshold (Ct) | |

| >30 | 10 |

| <30 | 12 |

| Not available | 4 |

| RECIPIENTS (N = 60) | |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (min–max) | 57 (21–74) |

| Male sex [n (%)] | 47 (78%) |

| Underlying liver disease | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 13 |

| Laënnec’s cirrhosis | 7 |

| Cryptogenic cirrhosis | 3 |

| Biliary cirrhosis | 1 |

| Drug-induced cirrhosis | 1 |

| Posthepatitic cirrhosis | 2 |

| Polycystic liver disease | 1 |

| Dysmetabolic liver disease | 1 |

| Previous graft rejection | 1 |

| Underlying kidney disease | |

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | 4 |

| IgA nephropathy | 4 |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 4 |

| Chronic renal failure | 4 |

| Renal hypoplasia | 3 |

| Lupus nephritis | 2 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 3 |

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 1 |

| Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | 1 |

| Renal carcinoma | 1 |

| Chronic pyelonephritis | 1 |

| Underlying heart disease | |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 1 |

| Transplant type [n (%)] | |

| Liver | 32 (49%) |

| Kidney | 32 (49%) |

| Heart | 1 (2%) |

| Recipient serostatus at the time of transplant [n (%)] | |

| IgG+ | 32 (53%) |

| IgG− | 1 (2%) |

| Not known | 27 (45%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrisli, E.; Gabrielli, L.; De Cillia, C.; Liberatore, A.; Piccirilli, G.; Venturoli, S.; Balboni, A.; Borgatti, E.C.; Cantiani, A.; Manzoli, L.; et al. Molecular Testing in Organ Biopsies and Perfusion Fluid Samples from Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Positive Donors. Viruses 2025, 17, 1611. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121611

Petrisli E, Gabrielli L, De Cillia C, Liberatore A, Piccirilli G, Venturoli S, Balboni A, Borgatti EC, Cantiani A, Manzoli L, et al. Molecular Testing in Organ Biopsies and Perfusion Fluid Samples from Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Positive Donors. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1611. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121611

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrisli, Evangelia, Liliana Gabrielli, Carlo De Cillia, Andrea Liberatore, Giulia Piccirilli, Simona Venturoli, Alice Balboni, Eva Caterina Borgatti, Alessia Cantiani, Lamberto Manzoli, and et al. 2025. "Molecular Testing in Organ Biopsies and Perfusion Fluid Samples from Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Positive Donors" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1611. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121611

APA StylePetrisli, E., Gabrielli, L., De Cillia, C., Liberatore, A., Piccirilli, G., Venturoli, S., Balboni, A., Borgatti, E. C., Cantiani, A., Manzoli, L., Alvaro, N., & Lazzarotto, T. (2025). Molecular Testing in Organ Biopsies and Perfusion Fluid Samples from Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Positive Donors. Viruses, 17(12), 1611. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121611