Determinants of Retroviral Integration and Implications for Gene Therapeutic MLV—Based Vectors and for a Cure for HIV-1 Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

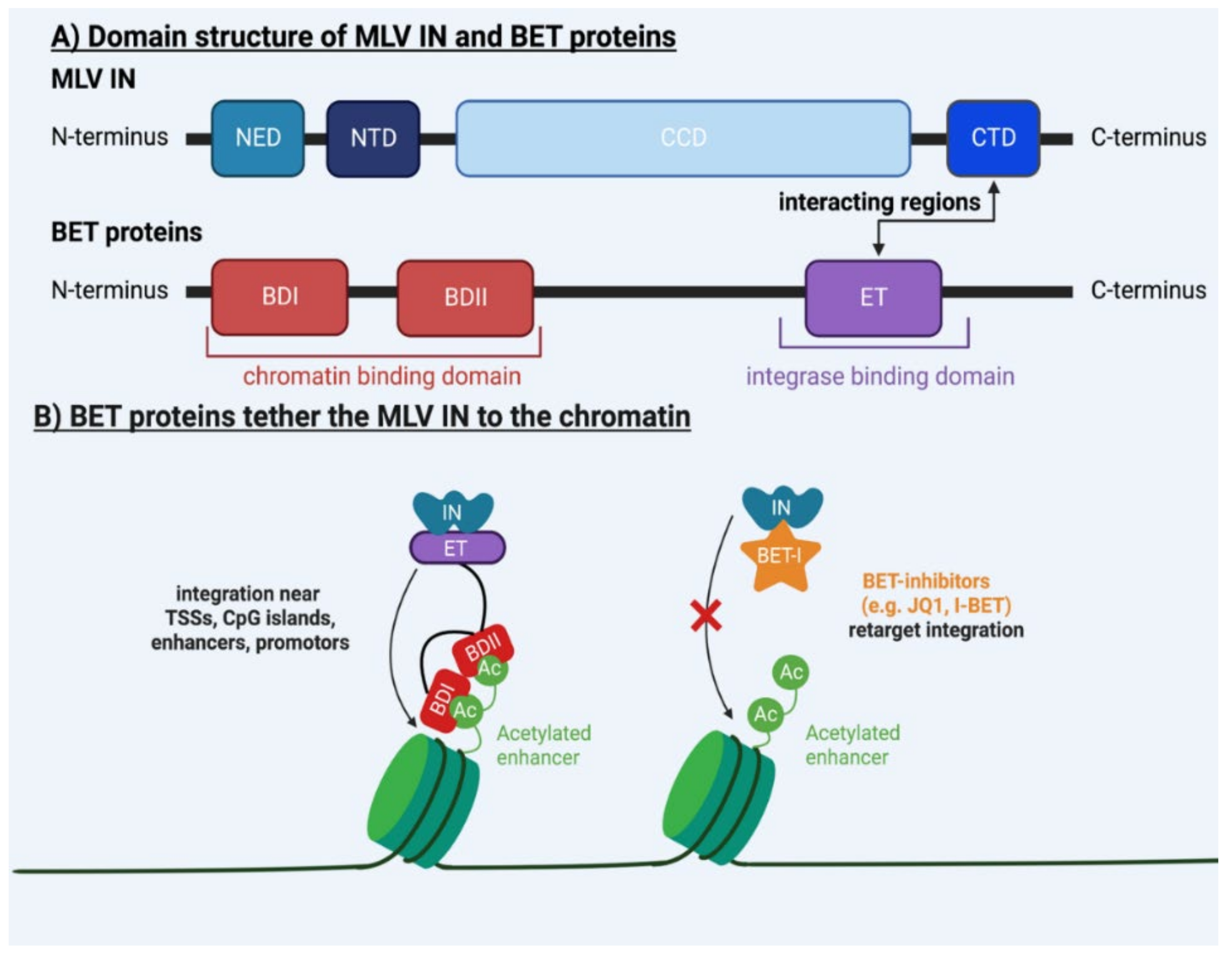

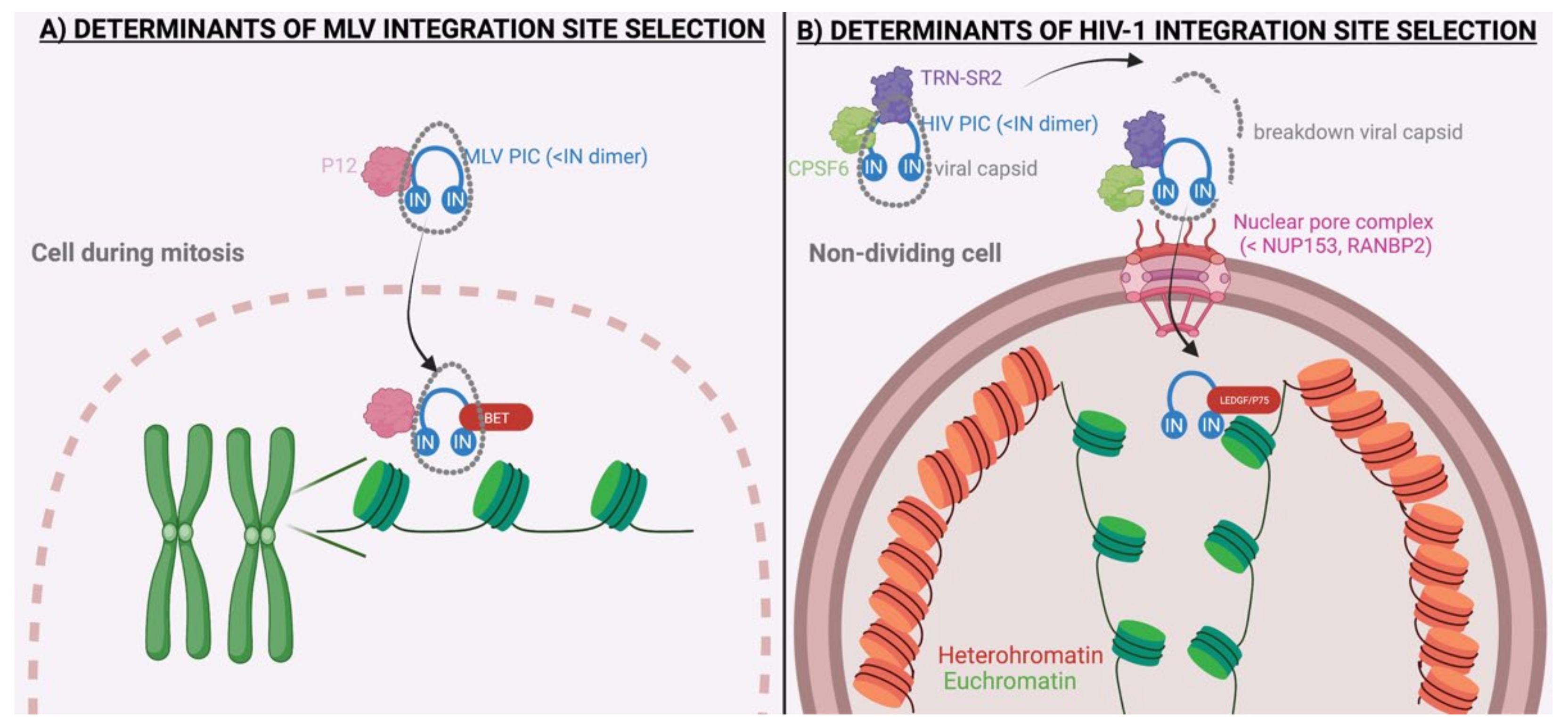

2. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying MLV Integration

3. Determinants of Integration Site Selection by Other Retroviruses

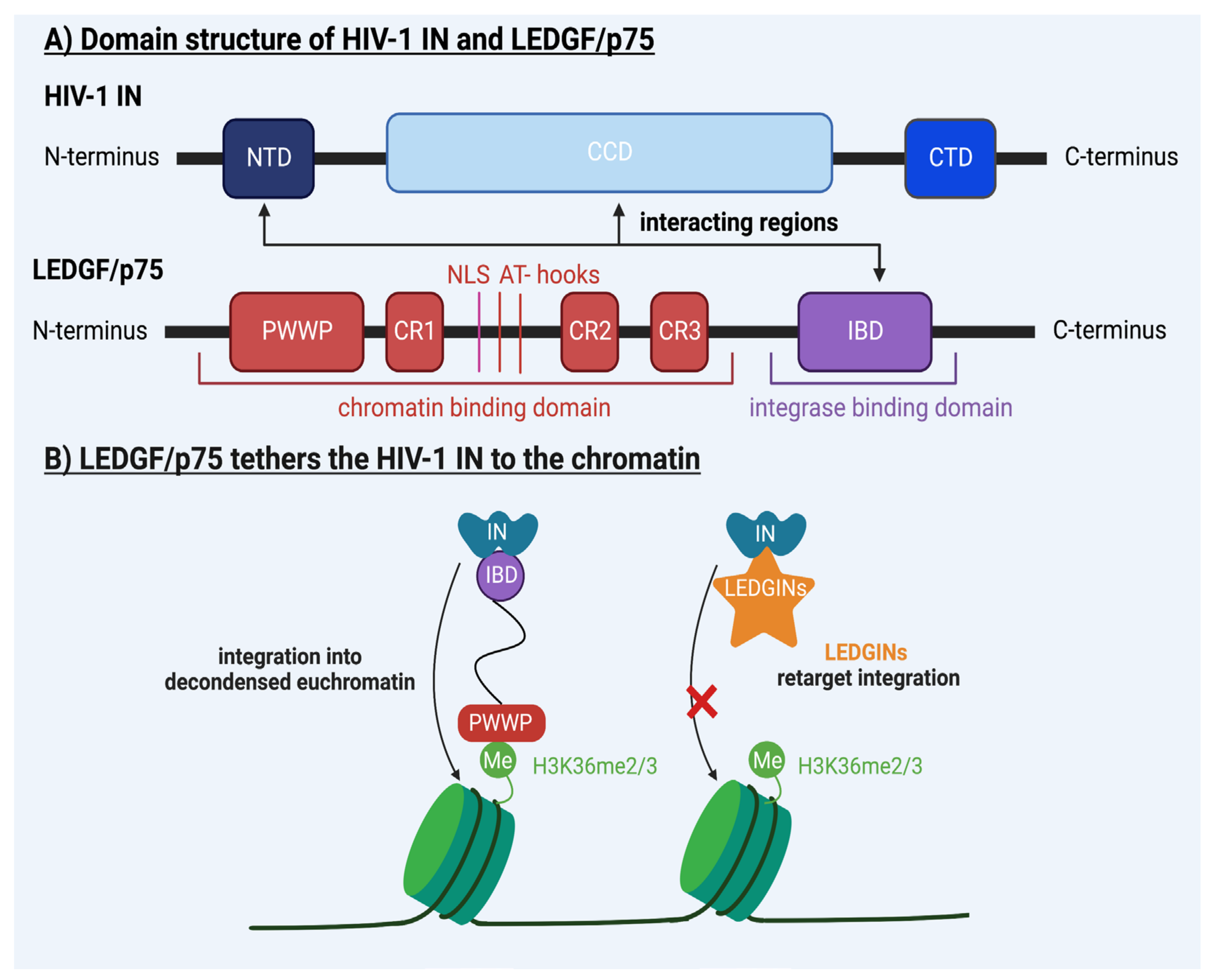

4. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying HIV-1 Integration

5. Integration Site Selection of Other Lentiviruses

6. Medical Applications of Retroviral Integration Site Selection

6.1. Safer Viral Vectors for Gene Therapy

6.2. Towards a Cure for HIV-1 Infection

6.3. Optimizing Oncovirotherapy

7. Retroviral Integration Sites Matter

8. Perspectives and Open Research Questions

8.1. Safer Viral Vectors for Gene Therapy

8.2. Towards an HIV-1 Cure

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Greenwood, A.D.; Ishida, Y.; O’Brien, S.P.; Roca, A.L.; Eiden, M.V. Transmission, Evolution, and Endogenization: Lessons Learned from Recent Retroviral Invasions. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2018, 82, e00044-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisole, S.; Saïb, A. Early Steps of Retrovirus Replicative Cycle. Retrovirology 2004, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos, D.O.; Li, M.; Craigie, R.; Lyumkis, D. Retroviral Integrase: Structure, Mechanism, and Inhibition. Enzymes 2022, 50, 249–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherepanov, P.; Maertens, G.N.; Hare, S. Structural Insights into the Retroviral DNA Integration Apparatus. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2011, 21, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, S.D.; Leipzig, J.; Shinn, P.; Ecker, J.R.; Bushman, F.D. Integration Targeting by Avian Sarcoma–Leukosis Virus and Human Immunodeficiency Virus in the Chicken Genome. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 12035–12044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiani, A.; Suerth, J.D.; Gandolfi, F.; Rizzi, E.; Severgnini, M.; De Bellis, G.; Schambach, A.; Mavilio, F. Genome–Wide Analysis of Alpharetroviral Integration in Human Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells. Genes 2014, 5, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.S.; Beitzel, B.F.; Schroder, A.R.W.; Shinn, P.; Chen, H.; Berry, C.C.; Ecker, J.R.; Bushman, F.D. Retroviral DNA Integration: ASLV, HIV, and MLV Show Distinct Target Site Preferences. PLoS Biol. 2004, 2, e234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, T.L.; Skalka, A.M.; Hanafusa, H. Integration of Rous Sarcoma Virus DNA into Chicken Embryo Fibroblasts: No Preferred Proviral Acceptor Site in the DNA of Clones of Singly Infected Transformed Chicken Cells. J. Virol. 1981, 40, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faschinger, A.; Rouault, F.; Sollner, J.; Lukas, A.; Salmons, B.; Günzburg, W.H.; Indik, S. Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus Integration Site Selection in Human and Mouse Genomes. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 1360–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantoulas, C.J.; Indik, S. Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus–Based Vector Transduces Non–Dividing Cells, Enters the Nucleus via a TNPO3–Independent Pathway and Integrates in a Less Biased Fashion than Other Retroviruses. Retrovirology 2014, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, J.; Akhtar, W.; Badhai, J.; Rust, A.G.; Rad, R.; Hilkens, J.; Berns, A.; van Lohuizen, M.; Wessels, L.F.A.; de Ridder, J. Chromatin Landscapes of Retroviral and Transposon Integration Profiles. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Crise, B.; Burgess, S.M. Transcription Start Regions in the Human Genome Are Favored Targets for MLV Integration. Science 2003, 300, 1749–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derse, D.; Crise, B.; Li, Y.; Princler, G.; Lum, N.; Stewart, C.; McGrath, C.F.; Hughes, S.H.; Munroe, D.J.; Wu, X. Human T–Cell Leukemia Virus Type 1 Integration Target Sites in the Human Genome: Comparison with Those of Other Retroviruses. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 6731–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melamed, A.; Witkover, A.D.; Laydon, D.J.; Brown, R.; Ladell, K.; Miners, K.; Rowan, A.G.; Gormley, N.; Price, D.A.; Taylor, G.P.; et al. Clonality of HTLV-2 in Natural Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babii, A.V.; Arkhipova, A.L.; Kovalchuk, S.N. Identification of Novel Integration Sites for Bovine Leukemia Virus Proviral DNA in Cancer Driver Genes in Cattle with Persistent Lymphocytosis. Virus Res. 2022, 317, 198813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, H.; Yamada, T.; Suzuki, M.; Nakahara, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Sentsui, H. Bovine Leukemia Virus Integration Site Selection in Cattle That Develop Leukemia. Virus Res. 2011, 156, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couez, D.; Deschamps, J.; Kettmann, R.; Stephens, R.M.; Gilden, R.V.; Burny, A. Nucleotide Sequence Analysis of the Long Terminal Repeat of Integrated Bovine Leukemia Provirus DNA and of Adjacent Viral and Host Sequences. J. Virol. 1984, 49, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettmann, R.; Cleuter, Y.; Mammerickx, M.; Meunier-Rotival, M.; Bernardi, G.; Burny, A.; Chantrenne, H. Genomic Integration of Bovine Leukamia Provirus:Comparison of Persistent Lymphocytosis with Lymph Node Form of Enzootic Bovine Leukosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1980, 77, 2577–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettmann, R.; Deschamps, J.; Couez, D.; Claustriaux, J.J.; Palm, R.; Burny, A. Chromosome Integration Domain for Bovine Leukemia Provirus in Tumors. J. Virol. 1983, 47, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinn, P.; Chen, H.; Berry, C.; Ecker, J.R.; Bushman, F.; Jolla, L. HIV-1 Integration in the Human Genome Favors Active Genes and Local Hotspots. Cell 2002, 110, 521–529. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A.; Defechereux, P.; Verdin, E. The Site of HIV-1 Integration in the Human Genome Determines Basal Transcriptional Activity and Response to Tat Transactivation. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 1726–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vansant, G.; Chen, H.C.; Zorita, E.; Trejbalová, K.; Miklík, D.; Filion, G.; Debyser, Z. The Chromatin Landscape at the HIV-1 Provirus Integration Site Determines Viral Expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 7801–7817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, J.; De Wit, F.; Parveen, N.; Debyser, Z. Single–Cell Imaging Shows That the Transcriptional State of the HIV-1 Provirus and Its Reactivation Potential Depend on the Integration Site. mBio 2022, 4, e0000722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crise, B.; Li, Y.; Yuan, C.; Morcock, D.R.; Whitby, D.; Munroe, D.J.; Arthur, L.O.; Wu, X. Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Integration Preference Is Similar to That of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 12199–12204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Moressi, C.J.; Scheetz, T.E.; Xie, L.; Tran, D.T.; Casavant, T.L.; Ak, P.; Benham, C.J.; Davidson, B.L.; McCray, P.B. Integration Site Choice of a Feline Immunodeficiency Virus Vector. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 8820–8823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocum, J.D.; Linde, I.; Rae, D.T.; Collins, C.P.; Matern, L.K.; Trobridge, G.D. Retargeted Foamy Virus Vectors Integrate Less Frequently Near Proto–Oncogenes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trobridge, G.D.; Miller, D.G.; Jacobs, M.A.; Allen, J.M.; Kiem, H.P.; Kaul, R.; Russell, D.W. Foamy Virus Vector Integration Sites in Normal Human Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 1498–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrenberghs, D.; Zurnic, I.; De Wit, F.; Acke, A.; Dirix, L.; Cereseto, A.; Debyser, Z.; Hendrix, J. Post–Mitotic BET–Induced Reshaping of Integrase Quaternary Structure Supports Wild–Type MLV Integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 1195–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rijck, J.; de Kogel, C.; Demeulemeester, J.; Vets, S.; El Ashkar, S.; Malani, N.; Bushman, F.D.; Landuyt, B.; Husson, S.J.; Busschots, K.; et al. The BET Family of Proteins Targets Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Integration near Transcription Start Sites. Cell Rep. 2013, 5, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Larue, R.C.; Plumb, M.R.; Malani, N.; Male, F.; Slaughter, A.; Kessl, J.J.; Shkriabai, N.; Coward, E.; Aiyer, S.S.; et al. BET Proteins Promote Efficient Murine Leukemia Virus Integration at Transcription Start Sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 12036–12041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.S.; Maetzig, T.; Maertens, G.N.; Sharif, A.; Rothe, M.; Weidner–Glunde, M.; Galla, M.; Schambach, A.; Cherepanov, P.; Schulz, T.F. Bromo– and Extraterminal Domain Chromatin Regulators Serve as Cofactors for Murine Leukemia Virus Integration. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 12721–12736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studamire, B.; Goff, S.P. Host Proteins Interacting with the Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Integrase: Multiple Transcriptional Regulators and Chromatin Binding Factors. Retrovirology 2008, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafave, M.C.; Varshney, G.K.; Gildea, D.E.; Wolfsberg, T.G.; Baxevanis, A.D.; Burgess, S.M. MLV Integration Site Selection Is Driven by Strong Enhancers and Active Promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 4257–4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ravin, S.S.; Su, L.; Theobald, N.; Choi, U.; Macpherson, J.L.; Poidinger, M.; Symonds, G.; Pond, S.M.; Ferris, A.L.; Hughes, S.H.; et al. Enhancers Are Major Targets for Murine Leukemia Virus Vector Integration. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4504–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debyser, Z.; Vansant, G.; Bruggemans, A.; Janssens, J.; Christ, F. Insight in HIV Integration Site Selection Provides a Block–and–Lock Strategy for a Functional Cure of HIV Infection. Viruses 2019, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherepanov, P.; Maertens, G.; Proost, P.; Devreese, B.; Van Beeumen, J.; Engelborghs, Y.; De Clercq, E.; Debyser, Z. HIV-1 Integrase Forms Stable Tetramers and Associates with LEDGF/P75 Protein in Human Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llano, M.; Vanegas, M.; Fregoso, O.; Saenz, D.; Chung, S.; Peretz, M.; Poeschla, E.M. LEDGF/P75 Determines Cellular Trafficking of Diverse Lentiviral but Not Murine Oncoretroviral Integrase Proteins and Is a Component of Functional Lentiviral Preintegration Complexes. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 9524–9537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsbers, R.; Ronen, K.; Vets, S.; Malani, N.; De Rijck, J.; McNeely, M.; Bushman, F.D.; Debyser, Z. LEDGF Hybrids Efficiently Retarget Lentiviral Integration into Heterochromatin. Mol. Ther. 2010, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, A.M.; Saenz, D.T.; Morrison, J.H.; Garcia–Rivera, J.A.; Peretz, M.; Llano, M.; Poeschla, E.M. LEDGF/P75 Proteins with Alternative Chromatin Tethers Are Functional HIV-1 Cofactors. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuffi, A.; Llano, M.; Poeschla, E.; Hoffmann, C.; Leipzig, J.; Shinn, P.; Ecker, J.R.; Bushman, F. A Role for LEDGF/P75 in Targeting HIV DNA Integration. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 1287–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, H.M.; Ronen, K.; Berry, C.; Llano, M.; Sutherland, H.; Saenz, D.; Bickmore, W.; Poeschla, E.; Bushman, F.D. Role of PSIP 1/LEDGF/P75 in Lentiviral Infectivity and Integration Targeting. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shun, M.C.; Raghavendra, N.K.; Vandegraaff, N.; Daigle, J.E.; Hughes, S.; Kellam, P.; Cherepanov, P.; Engelman, A. LEDGF/P75 Functions Downstream from Preintegration Complex Formation to Effect Gene–Specific HIV-1 Integration. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoder, K.E.; Rabe, A.J.; Fishel, R.; Larue, R.C. Strategies for Targeting Retroviral Integration for Safer Gene Therapy: Advances and Challenges. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, J.; Bruggemans, A.; Christ, F.; Debyser, Z. Towards a Functional Cure of HIV-1: Insight Into the Chromatin Landscape of the Provirus. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 636642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvaratskhelia, M.; Sharma, A.; Larue, R.C.; Serrao, E.; Engelman, A. Molecular Mechanisms of Retroviral Integration Site Selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 10209–10225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanaguru, M.; Bishop, K.N. Gammaretroviruses Tether to Mitotic Chromatin by Directly Binding Nucleosomal Histone Proteins. Microb. Cell 2018, 5, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elis, E.; Ehrlich, M.; Prizan–Ravid, A.; Laham-Karam, N.; Bacharach, E. P12 Tethers the Murine Leukemia Virus Pre–Integration Complex to Mitotic Chromosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1003103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanaguru, M.; Barry, D.J.; Benton, D.J.; O’Reilly, N.J.; Bishop, K.N. Murine Leukemia Virus P12 Tethers the Capsid–Containing Pre–Integration Complex to Chromatin by Binding Directly to Host Nucleosomes in Mitosis. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesbats, P.; Serrao, E.; Maskell, D.P.; Pye, V.E.; O’Reilly, N.; Lindemann, D.; Engelman, A.N.; Cherepanov, P. Structural Basis for Spumavirus GAG Tethering to Chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 5509–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W.M.; Brzezinski, J.D.; Aiyer, S.; Malani, N.; Gyuricza, M.; Bushman, F.D.; Roth, M.J. Viral DNA Tethering Domains Complement Replication–Defective Mutations in the P12 Protein of MuLV Gag. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9487–9492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyer, S.; Swapna, G.V.T.; Malani, N.; Aramini, J.M.; Schneider, W.M.; Plumb, M.R.; Ghanem, M.; Larue, R.C.; Sharma, A.; Studamire, B.; et al. Altering Murine Leukemia Virus Integration through Disruption of the Integrase and BET Protein Family Interaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 5917–5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acke, A.; Van Belle, S.; Louis, B.; Vitale, R.; Rocha, S.; Voet, T.; Debyser, Z.; Hofkens, J. Expansion Microscopy Allows High Resolution Single Cell Analysis of Epigenetic Readers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, B.L.; Larue, R.C.; Yuan, C.; Hess, S.; Kvaratskhelia, M.; Foster, M.P. Structure of the Brd4 et Domain Bound to a C–Terminal Motif from γ–Retroviral Integrases Reveals a Conserved Mechanism of Interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2086–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Ashkar, S.; Van Looveren, D.; Schenk, F.; Vranckx, L.S.; Demeulemeester, J.; De Rijck, J.; Debyser, Z.; Modlich, U.; Gijsbers, R. Engineering Next–Generation BET–Independent MLV Vectors for Safer Gene Therapy. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2017, 7, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nombela, I.; Michiels, M.; Van Looveren, D.; Marcelis, L.; el Ashkar, S.; Van Belle, S.; Bruggemans, A.; Tousseyn, T.; Schwaller, J.; Christ, F.; et al. BET–Independent Murine Leukemia Virus Integration Is Retargeted In Vivo and Selects Distinct Genomic Elements for Lymphomagenesis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyola, L.; Achuthan, V.; Gilroy, K.; Borland, G.; Kilbey, A.; MacKay, N.; Bell, M.; Hay, J.; Aiyer, S.; Fingerman, D.; et al. Disrupting MLV Integrase:BET Protein Interaction Biases Integration into Quiescent Chromatin and Delays but Does Not Eliminate Tumor Activation in a MYC/Runx2 Mouse Model. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1008154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ashkar, S.; De Rijck, J.; Demeulemeester, J.; Vets, S.; Madlala, P.; Cermakova, K.; Debyser, Z.; Gijsbers, R. BET–Independent MLV–Based Vectors Target Away from Promoters and Regulatory Elements. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2014, 3, e179-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyer, S.; Rossi, P.; Malani, N.; Schneider, W.M.; Chandar, A.; Bushman, F.D.; Montelione, G.T.; Roth, M.J. Structural and Sequencing Analysis of Local Target DNA Recognition by MLV Integrase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 5647–5663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinski, M.K.; Yamashita, M.; Emerman, M.; Ciuffi, A.; Marshall, H.; Crawford, G.; Collins, F.; Shinn, P.; Leipzig, J.; Hannenhalli, S.; et al. Retroviral DNA Integration: Viral and Cellular Determinants of Target–Site Selection. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocwieja, K.E.; Brady, T.L.; Ronen, K.; Huegel, A.; Roth, S.L.; Schaller, T.; James, L.C.; Towers, G.J.; Young, J.A.T.; Chanda, S.K.; et al. HIV Integration Targeting: A Pathway Involving Transportin–3 and the Nuclear Pore Protein RanBP2. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1001313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nunzio, F.; Frickeb, T.; Miccioc, A.; Valle-Casusob, J.C.; Perezb, P.; Souquea, P.; Rizzid, E.; Severgninid, M.; Mavilioc, F.; Charneaua, P.; et al. Nup153 and Nup98 Bind the HIV-1 Core and Contribute to the Early Steps of HIV-1 Replication. Virology 2013, 440, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelek, M.; Casartelli, N.; Pellin, D.; Rizzi, E.; Souque, P.; Severgnini, M.; Di Serio, C.; Fricke, T.; Diaz–Griffero, F.; Zimmer, C.; et al. Chromatin Organization at the Nuclear Pore Favours HIV Replication. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaller, T.; Ocwieja, K.E.; Rasaiyaah, J.; Price, A.J.; Brady, T.L.; Roth, S.L.; Hué, S.; Fletcher, A.J.; Lee, K.E.; KewalRamani, V.N.; et al. HIV-1 Capsid–Cyclophilin Interactions Determine Nuclear Import Pathway, Integration Targeting and Replication Efficiency. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millner, L.M.; Linder, M.W.; Direct, R.V.J. Visualization of HIV-1 Replication Intermediates Shows That Viral Capsid and CPSF6 Modulate HIV-1 Intra–Nuclear Invasion and Integration. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 1717–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achuthan, V.; Perreira, J.M.; Sowd, G.A.; Puray-Chavez, M.; Mcdougall, W.M.; Paulucci-Holthauzen, A.; Wu, X.; Fadel, H.J.; Eric, M.; Multani, A.S.; et al. Capsid–CPSF6 Interaction Licenses Nuclear HIV-1 Trafficking to Sites of Viral DNA Integration Vasudevan. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 24, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheedi, S.; Shun, M.C.; Serrao, E.; Sowd, G.A.; Qian, J.; Hao, C.; Dasgupta, T.; Engelman, A.N.; Skowronski, J. The Cleavage and Polyadenylation Specificity Factor 6 (CPSF6) Subunit of the Capsid–Recruited Pre–Messenger RNA Cleavage Factor I (CFIm) Complex Mediates HIV-1 Integration into Genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 11809–11819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowd, G.A.; Serrao, E.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Fadel, H.J.; Poeschla, E.M.; Engelman, A.N. A Critical Role for Alternative Polyadenylation Factor CPSF6 in Targeting HIV-1 Integration to Transcriptionally Active Chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E1054–E1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, M.; Hendrix, J.; Busschots, K.; Boons, E.; Deleersnijder, A.; Gerard, M.; Christ, F.; Debyser, Z. In Vitro DNA Tethering of HIV-1 Integrase by the Transcriptional Coactivator LEDGF/P75. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 410, 811–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, F.; Shaw, S.; Demeulemeester, J.; Desimmie, B.A.; Marchan, A.; Butler, S.; Smets, W.; Chaltin, P.; Westby, M.; Debyser, Z.; et al. Small–Molecule Inhibitors of the LEDGF/P75 Binding Site of Integrase Block HIV Replication and Modulate Integrase Multimerization. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 4365–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokken, J.; De Rijck, J.; Christ, F.; Debyser, Z. Protein–Protein and Protein–Chromatin Interactions of LEDGF/P75 as Novel Drug Targets. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2017, 24, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llano, M.; Vanegas, M.; Hutchins, N.; Thompson, D.; Delgado, S.; Poeschla, E.M. Identification and Characterization of the Chromatin–Binding Domains of the HIV-1 Integrase Interactor LEDGF/P75. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 360, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherepanov, P.; Devroe, E.; Silver, P.A.; Engelman, A. Identification of an Evolutionarily Conserved Domain in Human Lens Epithelium–Derived Growth Factor/Transcriptional Co–Activator P75 (LEDGF/P75) That Binds HIV-1 Integrase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 48883–48892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llano, M.; Delgado, S.; Vanegas, M.; Poeschla, E.M. Lens Epithelium–Derived Growth Factor/P75 Prevents Proteasomal Degradation of HIV-1 Integrase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 55570–55577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Jurado, K.A.; Wu, X.; Shun, M.C.; Li, X.; Ferris, A.L.; Smith, S.J.; Patel, P.A.; Fuchs, J.R.; Cherepanov, P.; et al. HRP2 Determines the Efficiency and Specificity of HIV-1 Integration in LEDGF/P75 Knockout Cells but Does Not Contribute to the Antiviral Activity of a Potent LEDGF/P75–Binding Site Integrase Inhibitor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 11518–11530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debyser, Z.; Christ, F.; De Rijck, J.; Gijsbers, R. Host Factors for Retroviral Integration Site Selection. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Bao, J.; Yan, H.; Xie, L.; Qin, W.; Ning, H.; Huang, S.; Cheng, J.; Zhi, R.; Li, Z.; et al. Competition between PAF1 and MLL1/COMPASS Confers the Opposing Function of LEDGF/P75 in HIV Latency and Proviral Reactivation. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranckx, L.S.; Demeulemeester, J.; Saleh, S.; Boll, A.; Vansant, G.; Schrijvers, R.; Weydert, C.; Battivelli, E.; Verdin, E.; Cereseto, A.; et al. LEDGIN–Mediated Inhibition of Integrase–LEDGF/P75 Interaction Reduces Reactivation of Residual Latent HIV. eBioMedicine 2016, 8, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turlure, F.; Maertens, G.; Rahman, S.; Cherepanov, P.; Engelman, A. A Tripartite DNA–Binding Element, Comprised of the Nuclear Localization Signal and Two AT–Hook Motifs, Mediates the Association of LEDGF/P75 with Chromatin in Vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 1653–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranckx, L.S.; Demeulemeester, J.; Debyser, Z.; Gijsbers, R. Towards a Safer, More Randomized Lentiviral Vector Integration Profile Exploring Artificial LEDGF Chimeras. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, F.; Voet, A.; Marchand, A.; Nicolet, S.; Desimmie, B.A.; Marchand, D.; Bardiot, D.; Van der Veken, N.J.; Van Remoortel, B.; Strelkov, S.V.; et al. Rational Design of Small–Molecule Inhibitors of the LEDGF/P75–Integrase Interaction and HIV Replication. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, F.; Debyser, Z. The LEDGF/P75 Integrase Interaction, a Novel Target for Anti–HIV Therapy. Virology 2013, 435, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandekerckhove, L.; Christ, F.; Van Maele, B.; De Rijck, J.; Gijsbers, R.; Van den Haute, C.; Witvrouw, M.; Debyser, Z. Transient and Stable Knockdown of the Integrase Cofactor LEDGF/P75 Reveals Its Role in the Replication Cycle of Human Immunodeficiency Virus. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 1886–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rijck, J.; Vandekerckhove, L.; Gijsbers, R.; Hombrouck, A.; Hendrix, J.; Vercammen, J.; Engelborghs, Y.; Christ, F.; Debyser, Z. Overexpression of the Lens Epithelium–Derived Growth Factor/P75 Integrase Binding Domain Inhibits Human Immunodeficiency Virus Replication. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 11498–11509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiang, M.; Jones, G.S.; Niedziela–Majka, A.; Kan, E.; Lansdon, E.B.; Huang, W.; Hung, M.; Samuel, D.; Novikov, N.; Xu, Y.; et al. New Class of HIV-1 Integrase (IN) Inhibitors with a Dual Mode of Action. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 21189–21203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desimmie, B.A.; Schrijvers, R.; Demeulemeester, J.; Borrenberghs, D.; Weydert, C.; Thys, W.; Vets, S.; Van Remoortel, B.; Hofkens, J.; De Rijck, J.; et al. LEDGINs Inhibit Late Stage HIV-1 Replication by Modulating Integrase Multimerization in the Virions. Retrovirology 2013, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessl, J.J.; Li, M.; Ignatov, M.; Shkriabai, N.; Eidahl, J.O.; Feng, L.; Musier–Forsyth, K.; Craigie, R.; Kvaratskhelia, M. FRET Analysis Reveals Distinct Conformations of in Tetramers in the Presence of Viral DNA or LEDGF/P75. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 9009–9022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansant, G.; Vranckx, L.S.; Zurnic, I.; Van Looveren, D.; Van De Velde, P.; Nobles, C.; Gijsbers, R.; Christ, F.; Debyser, Z. Impact of LEDGIN Treatment during Virus Production on Residual HIV-1 Transcription. Retrovirology 2019, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzman, M.; Sudol, M. Mapping Domains of Retroviral Integrase Responsible for Viral DNA Specificity and Target Site Selection by Analysis of Chimeras between Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 and Visna Virus Integrases. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 5687–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzman, M.; Sudol, M.; Pufnock, J.S.; Zeto, S.; Skinner, L.M. Mapping Target Site Selection for the Non–Specific Nuclease Activities of Retroviral Integrase. Virus Res. 2000, 66, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzman, M.; Sudol, M. Mapping Viral DNA Specificity to the Central Region of Integrase by Using Functional Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1/Visna Virus Chimeric Proteins. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 1744–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.L.; Skinner, L.M.; Sudol, M.; Katzman, M. Use of Patient–Derived Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Integrases To Identify a Protein Residue That Affects Target Site Selection. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 7756–7762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demeulemeester, J.; Vets, S.; Schrijvers, R.; Madlala, P.; De Maeyer, M.; De Rijck, J.; Ndung, U.T.; Debyser, Z.; Gijsbers, R. HIV-1 Integrase Variants Retarget Viral Integration and Are Associated with Disease Progression in a Chronic Infection Cohort. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 16, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapaillerie, D.; Lelandais, B.; Mauro, E.; Lagadec, F.; Tumiotto, C.; Miskey, C.; Ferran, G.; Kuschner, N.; Calmels, C.; Métifiot, M.; et al. Modulation of the Intrinsic Chromatin Binding Property of HIV-1 Integrase by LEDGF/P75. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 11241–11256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benleulmi, M.S.; Matysiak, J.; Robert, X.; Miskey, C.; Mauro, E.; Lapaillerie, D.; Lesbats, P.; Chaignepain, S.; Henriquez, D.R.; Calmels, C.; et al. Modulation of the Functional Association between the HIV-1 Intasome and the Nucleosome by Histone Amino–Terminal Tails. Retrovirology 2017, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodi, P.J.; Ernst, J.A.; Kuszewski, J.; Hickman, A.B.; Engelman, A.; Craigie, R.; Clore, G.M.; Gronenborn, A.M. Solution Structure of the DNA Binding Domain of HIV-1 Integras. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 9826–9833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, R.; Wang, G.G. Tudor: A Versatile Family of Histone Methylation “readers” Histone Modification and Its “Reader” Proteins in Gene Regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2013, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Yao, X. Posttranslational Modifications of HIV-1 Integrase by Various Cellular Proteins during Viral Replication. Viruses 2013, 5, 1787–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winans, S.; Yu, H.J.; de los Santos, K.; Wang, G.Z.; KewalRamani, V.N.; Goff, S.P. A Point Mutation in HIV-1 Integrase Redirects Proviral Integration into Centromeric Repeats. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, J.; Lesbats, P.; Mauro, E.; Lapaillerie, D.; Dupuy, J.W.; Lopez, A.P.; Benleulmi, M.S.; Calmels, C.; Andreola, M.L.; Ruff, M.; et al. Modulation of Chromatin Structure by the FACT Histone Chaperone Complex Regulates HIV-1 Integration. Retrovirology 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winans, S.; Larue, R.C.; Abraham, C.M.; Shkriabai, N.; Skopp, A.; Winkler, D.; Kvaratskhelia, M.; Beemon, K.L. The FACT Complex Promotes Avian Leukosis Virus DNA Integration Shelby. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00082-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, D.D.; Muthurajan, U.M.; Hieb, A.R.; Luger, K. Histone Chaperone FACT Coordinates Nucleosome Interaction through Multiple Synergistic Binding Events. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 41883–41892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland, N.G.; Jenkins, N.A.; Cooper, G.M. Integration of Rous Sarcoma Virus DNA during Transfection. Cell 1981, 23, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, A.L.; Sudol, M.; Katzman, M. An Amino Acid in the Central Catalytic Domain of Three Retroviral Integrases That Affects Target Site Selection in Nonviral DNA. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 3838–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Pandey, K.K.; Bera, S.; Vora, A.C.; Grandgenett, D.P.; Aihara, H. A Possible Role for the Asymmetric C–Terminal Domain Dimer of Rous Sarcoma Virus Integrase in Viral DNA Binding. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, K.K.; Bera, S.; Shi, K.; Aihara, H.; Grandgenett, D.P. A C–Terminal “Tail” Region in the Rous Sarcoma Virus Integrase Provides High Plasticity of Functional Integrase Oligomerization during Intasome Assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 5018–5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, A.; Buttitta, F.; Miyazaki, S.; Gallahan, D.; Smith, G.H.; Callahan, R. Int–6, a Highly Conserved, Widely Expressed Gene, Is Mutated by Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus in Mammary Preneoplasia. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 1932–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanager, B. A Common Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus Integration Site in Chemically Induced Precancerous Mammary Hyperplasias. Virology 2011, 368, 2006–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lowther, W.; Wiley, K.; Smith, G.H.; Callahan, R. A New Common Integration Site, Int7, for the Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus in Mouse Mammary Tumors Identifies a Gene Whose Product Has Furin–Like and Thrombospondin–Like Sequences. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 10093–10096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed, A.; Fitzgerald, T.W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Birney, E.; Bangham, C.R.M. Selective Clonal Persistence of Human Retroviruses in Vivo: Radial Chromatin Organization, Integration Site, and Host Transcription. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, K.; Wu, X.; Taniguchi, Y.; Yasunaga, J.I.; Satou, Y.; Okayama, A.; Nosaka, K.; Matsuoka, M. Preferential Selection of Human T–Cell Leukemia Virus Type I Provirus Integration Sites in Leukemic versus Carrier States. Blood 2005, 106, 1048–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, I.; Mortreux, F.; Cavrois, M.; Leroy, A.; Gessain, A.; Wain–Hobson, S.; Wattel, E. Host Sequences Flanking the Human T–Cell Leukemia Virus Type 1 Provirus In Vivo. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 2305–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozawa, T.; Itoyama, T.; Sadamori, N.; Yamada, Y.; Hata, T.; Tomonaga, M.; Isobe, M. Rapid Isolation of Viral Integration Site Reveals Frequent Integration of HTLV-1 into Expressed Loci. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 49, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asquith, B.; Mosley, A.J.; Heaps, A.; Tanaka, Y.; Taylor, G.P.; McLean, A.R.; Bangham, C.R.M. Quantification of the Virus–Host Interaction in Human T Lymphotropic Virus I Infection. Retrovirology 2005, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanai, S.; Nitta, T.; Shoda, M.; Tanaka, M.; Iso, N.; Mizoguchi, I.; Yashiki, S.; Sonoda, S.; Hasegawa, Y.; Nagasawa, T.; et al. Integration of Human T–Cell Leukemia Virus Type 1 in Genes of Leukemia Cells of Patients with Adult T–Cell Leukemia. Cancer Sci. 2004, 95, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederer, H.A.; Laydon, D.J.; Melamed, A.; Elemans, M.; Asquith, B.; Matsuoka, M.; Bangham, C.R.M. HTLV-1 Proviral Integration Sites Differ between Asymptomatic Carriers and Patients with HAM/TSP. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meekings, K.N.; Leipzig, J.; Bushman, F.D.; Taylor, G.P.; Bangham, C.R.M. HTLV-1 Integration into Transcriptionally Active Genomic Regions Is Associated with Proviral Expression and with HAM/TSP. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, I.; Mortreux, F.; Gabet, A.S.; Jonsson, C.B.; Wattel, E. Basis of HTLV Type 1 Target Site Selection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2000, 16, 1653–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed, A.; Laydon, D.J.; Gillet, N.A.; Tanaka, Y.; Taylor, G.P.; Bangham, C.R.M. Genome–Wide Determinants of Proviral Targeting, Clonal Abundance and Expression in Natural HTLV-1 Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallin, A.J.; Maertens, G.N.; Bangham, C.R. Host Determinants of HTLV-1 Integration Site Preference. Retrovirology 2015, 12, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertens, G.N. B′–Protein Phosphatase A Is a Functional Binding Partner of Delta–Retroviral Integrase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasaka, T.; Oguma, K.; Sentsui, H. Distribution and Characteristics of Bovine Leukemia Virus Integration Sites in the Host Genome at Three Different Clinical Stages of Infection. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabi, A.S.; Jaffar, S.; Ariyoshi, K.; Blanchard, T.; Schim Van Der Loeff, M.; Awasana, A.A.; Corrah, T.; Sabally, S.; Sarge–Njie, R.; Cham–Jallow, F.; et al. Plasma Viral Load, CD4 Cell Percentage, HLA and Survival of HIV-1, HIV-2, and Dually Infected Gambian Patients. Aids 2003, 17, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyamweya, S.; Hegedus, A.; Jaye, A.; Rowland–Jones, S.; Flanagan, K.L.; Macallan, D.C. Comparing HIV-1 and HIV-2 Infection: Lessons for Viral Immunopathogenesis. Rev. Med. Virol. 2013, 23, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, N.; Aaby, P.; Tedder, R.; Whittle, H.; Jaffar, S.; Schim van der Loeff, M.; Ariyoshi, K.; Harding, E.; Tamba N’Gom, P.; Dias, F.; et al. Low Level Viremia and High CD4% Predict Normal Survival in a Cohort of HIV Type–2–Infected Villagers. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2002, 18, 1167–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacNeil, A.; Sankalé, J.-L.; Meloni, S.T.; Sarr, A.D.; Mboup, S.; Kanki, P. Genomic Sites of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 2 (HIV-2) Integration: Similarities to HIV-1 In Vitro and Possible Differences In Vivo. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 7316–7321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, S.; Vranckx, L.; Gijsbers, R.; Christ, F.; Debyser, Z. Insight into HIV-2 Latency May Disclose Strategies for a Cure for HIV-1 Infection. J. Virus Erad. 2017, 3, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, M.J.; Peña, Á.; Vallejo, F.G. A Genomic and Bioinformatics Analysis of the Integration of HIV in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2011, 27, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monse, H.; Laufs, S.; Kuate, S.; Zeller, W.J.; Fruehauf, S.; Überla, K. Viral Determinants of Integration Site Preferences of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus–Based Vectors. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 8145–8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busschots, K.; Vercammen, J.; Emiliani, S.; Benarous, R.; Engelborghs, Y.; Christ, F.; Debyser, Z. The Interaction of LEDGF/P75 with Integrase Is Lentivirus–Specific and Promotes DNA Binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 17841–17847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowrouzi, A.; Dittrich, M.; Klanke, C.; Heinkelein, M.; Rammling, M.; Dandekar, T.; von Kalle, C.; Rethwilm, A. Genome–Wide Mapping of Foamy Virus Vector Integrations into a Human Cell Line. J. Gen. Virol. 2006, 87, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, B.C.; Keyser, K.A.; Trobridge, G.D.; Peterson, L.J.; Miller, D.G.; Jacobs, M.; Kaul, R.; Kiem, H.P. Unique Integration Profiles in a Canine Model of Long–Term Repopulating Cells Transduced with Gammaretrovirus, Lentivirus, or Foamy Virus. Hum. Gene Ther. 2007, 18, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olszko, M.E.; Adair, J.E.; Linde, I.; Rae, D.T.; Trobridge, P.; Hocum, J.D.; Rawlings, D.J.; Kiem, H.P.; Trobridge, G.D. Foamy Viral Vector Integration Sites in SCID–Repopulating Cells after MGMTPK–Mediated in Vivo Selection. Gene Ther. 2015, 22, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesbats, P.; Parissi, V. Retroviral Integration Site Selection: A Running Gag? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 5, 569–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schwedler, U.; Kornbluth, R.S.; Trono, D. The Nuclear Localization Signal of the Matrix Protein of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Allows the Establishment of Infection in Macrophages and Quiescent T Lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 6992–6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinzinger, N.K.; Bukrinsky, M.I.; Haggerty, S.A.; Ragland, A.M.; Kewalramani, V.; Lee, M.A.; Gendelman, H.E.; Ratner, L.; Stevenson, M.; Emerman, M. The Vpr Protein of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Influences Nuclear Localization of Viral Nucleic Acids in Nondividing Host Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 7311–7315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouchier, R.A.; Malim, M.H. Nuclear Import of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type–1 Preintegration Complexes. Adv. Virus Res. 1999, 52, 275–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wight, D.J.; Boucherit, V.C.; Nader, M.; Allen, D.J.; Taylor, I.A.; Bishop, K.N. The Gammaretroviral P12 Protein Has Multiple Domains That Function during the Early Stages of Replication. Retrovirology 2012, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wight, D.J.; Boucherit, V.C.; Wanaguru, M.; Elis, E.; Hirst, E.M.A.; Li, W.; Ehrlich, M.; Bacharach, E.; Bishop, K.N. The N–Terminus of Murine Leukaemia Virus P12 Protein Is Required for Mature Core Stability. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, Y. The Bromodomain and Extra–Terminal Domain (BET) Family: Functional Anatomy of BET Paralogous Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Sowa, M.E.; Ottinger, M.; Smith, J.A.; Shi, Y.; Harper, J.W.; Howley, P.M. The Brd4 Extraterminal Domain Confers Transcription Activation Independent of PTEFb by Recruiting Multiple Proteins, Including NSD3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011, 31, 2641–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruyama, T.; Hiratsuka, T.; Yamada, N. Hotspots of MLV Integration in the Hematopoietic Tumor Genome. Oncogene 2017, 36, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowa, A.; Okeomab, C.M.; Lovsinc, N.; de las Herasd, M.; Taylore, T.H.; Peterlinc, B.M.; Rossb, S.R. Enhanced Replication and Pathogenesis of Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus in Mice Defective in the Murine APOBEC3 Gene. Virology 2009, 385, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNally, M.M.; Wahlin, K.J.; Canto–Soler, M.V. Endogenous Expression of ASLV Viral Proteins in Specific Pathogen Free Chicken Embryos: Relevance for the Developmental Biology Research Field. BMC Dev. Biol. 2010, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichhorn, P.J.A.; Creyghton, M.P.; Bernards, R. Protein Phosphatase A Regulatory Subunits and Cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2009, 1795, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanker, V.; Trincucci, G.; Heim, H.M.; Duong, H.T.F. Protein Phosphatase A Impairs IFNα–Induced Antiviral Activity against the Hepatitis C Virus through the Inhibition of STAT1 Tyrosine Phosphorylation. J. Viral Hepat. 2013, 20, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeulemeester, J.; De Rijck, J.; Gijsbers, R.; Debyser, Z. Retroviral Integration: Site Matters: Mechanisms and Consequences of Retroviral Integration Site Selection. BioEssays 2015, 37, 1202–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Craigie, R. The Road to Chromatin–Nuclear Entry of Retroviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rijck, J.; Vandekerckhove, L.; Christ, F.; Debyser, Z. Lentiviral Nuclear Import: A Complex Interplay between Virus and Host. BioEssays 2007, 29, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, R.; Zhou, Y.; Elleder, D.; Diamond, T.L.; Ghislain, M.C.; Irelan, J.T.; Chiang, C.; Tu, B.P.; Jesus, P.D.; De Lilley, E.; et al. Global Analysis of Host–Pathogen Interactions That Regulate Early Stage HIV-1 Replication. Cell 2009, 135, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, J.A. Identification of Host Proteins Required for HIV Infection through a Functional Genomic Screen. Pediatrics 2008, 122 (Suppl. 4), 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, C.L.; Prakobwanakit, S.; Mosessian, S.; Chow, S.A. Integrase Interacts with Nucleoporin NUP153 To Mediate the Nuclear Import of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 6522–6533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, J.; Machado, A.K.; Lyonnais, S.; Chamontin, C.; Gärtner, K.; Léger, T.; Henriquet, C.; Garcia, C.; Portilho, D.M.; Pugnière, M.; et al. Transportin–1 Binds to the HIV-1 Capsid via a Nuclear Localization Signal and Triggers Uncoating. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1840–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Lian, X.; Gao, C.; Sun, X.; Einkauf, K.B.; Chevalier, J.M.; Chen, S.M.Y.; Hua, S.; Rhee, B.; Chang, K.; et al. Distinct Viral Reservoirs in Individuals with Spontaneous Control of HIV-1. Nature 2020, 585, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marini, B.; Kertesz–Farkas, A.; Ali, H.; Lucic, B.; Lisek, K.; Manganaro, L.; Pongor, S.; Luzzati, R.; Recchia, A.; Mavilio, F.; et al. Nuclear Architecture Dictates HIV-1 Integration Site Selection. Nature 2015, 521, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruelas, D.S.; Greene, W.C. An Integrated Overview of HIV-1 Latency. Cell 2013, 155, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahabieh, M.S.; Battivelli, E.; Verdin, E. Understanding HIV Latency: The Road to an HIV Cure. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015, 66, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.C.; Marin, M.; Singh, P.K.; Achuthan, V.; Prellberg, M.J.; Palermino–Rowland, K.; Lan, S.; Tedbury, P.R.; Sarafianos, S.G.; Engelman, A.N.; et al. HIV-1 Replication Complexes Accumulate in Nuclear Speckles and Integrate into Speckle–Associated Genomic Domains. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensen, E.; Mueller, F.; Scoca, V.; Parmar, J.J.; Souque, P.; Zimmer, C.; Di Nunzio, F. Clustering and Reverse Transcription of HIV-1 Genomes in Nuclear Niches of Macrophages. EMBO J. 2021, 40, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucic, B.; Chen, H.C.; Kuzman, M.; Zorita, E.; Wegner, J.; Minneker, V.; Wang, W.; Fronza, R.; Laufs, S.; Schmidt, M.; et al. Spatially Clustered Loci with Multiple Enhancers Are Frequent Targets of HIV-1 Integration. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Shen, J. From Super–Enhancer Non–Coding RNA to Immune Checkpoint: Frameworks to Functions. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, R.; Sandelin, A. Determinants of Enhancer and Promoter Activities of Regulatory Elements. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 21, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinn, P.L.; Sauter, S.L.; McCray, P.B. Gene Therapy Progress and Prospects: Development of Improved Lentiviral and Retroviral Vectors–Design, Biosafety, and Production. Gene Ther. 2005, 12, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiuti, A.; Cassani, B.; Andolfi, G.; Mirolo, M.; Biasco, L.; Recchia, A.; Urbinati, F.; Valacca, C.; Scaramuzza, S.; Aker, M.; et al. Multilineage Hematopoietic Reconstitution without Clonal Selection in ADA–SCID Patients Treated with Stem Cell Gene Therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 2233–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordignon, C.; Roncarolo, M.G. Therapeutic Applications for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Gene Transfer. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranzani, M.; Annunziato, S.; Adams, D.J.; Montini, E. Cancer Gene Discovery: Exploiting Insertional Mutagenesis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2013, 11, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kool, J.; Berns, A. High–Throughput Insertional Mutagenesis Screens in Mice to Identify Oncogenic Networks. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Jenkins, N.A.; Copeland, N.G. Insertional Mutagenesis Identifies Genes That Promote the Immortalization of Primary Bone Marrow Progenitor Cells. Blood 2005, 106, 3932–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, M.G.; Schmidt, M.; Schwarzwaelder, K.; Stein, S.; Siler, U.; Koehl, U.; Glimm, H.; Kühlcke, K.; Schilz, A.; Kunkel, H.; et al. Correction of X–Linked Chronic Granulomatous Disease by Gene Therapy, Augmented by Insertional Activation of MDS1–EVI1, PRDM16 or SETBP1. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortex, P. LMO2–Associated Clonal T Cell Proliferation in Two Patients after Gene Therapy for SCOD–X1. Science 2003, 302, 1181–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina, S.; von Kalle, C.; Schmidt, M.; Le Deist, F.; Wulffraat, N.; McIntyre, E.; Radford, I.; Villeval, J.-L.; Fraser, C.C.; Cavazzana-Calvo, M.; et al. A Serious Adverse Event after Successful Gene Therapy for X–Linked Severe Combined Immunodeficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 255–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boztug, K.; Schmidt, M.; Schwarzer, A.; Banerjee, P.P.; Díez, I.A.; Dewey, R.A.; Böhm, M.; Nowrouzi, A.; Ball, C.R.; Glimm, H.; et al. Stem–Cell Gene Therapy for the Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, C.J.; Boztug, K.; Paruzynski, A.; Witzel, M.; Schwarzer, A.; Rothe, M.; Modlich, U.; Beier, R.; Göhring, G.; Steinemann, D.; et al. Gene Therapy for Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome–Long–Term Efficacy and Genotoxicity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, S.; Ott, M.G.; Schultze–Strasser, S.; Jauch, A.; Burwinkel, B.; Kinner, A.; Schmidt, M.; Krämer, A.; Schwäble, J.; Glimm, H.; et al. Genomic Instability and Myelodysplasia with Monosomy 7 Consequent to EVI1 Activation after Gene Therapy for Chronic Granulomatous Disease. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohn, D.B. Historical Perspective on the Current Renaissance for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Gene Therapy. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 2017, 31, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davé, U.P.; Jenkins, N.A.; Copeland, N.G. Gene Therapy Insertional Mutagenesis Insights. Science 2004, 303, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, N.-B.; Bottero, V.; Schmidt, M.C.; von Kalle, C.; Verma, I.M. Therapeutic Gene Causing Lymphoma. Nature 2006, 440, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.F.; von Ruden, T.; Kantoff, P.W.; Garber, C.; Seiberg, M.; Rüther, U.; Anderson, W.F.; Wagner, E.F.; Gilboa, E. Self–Inactivating Retroviral Vectors Designed for Transfer of Whole Genes into Mammalian Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 3194–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesana, D.; Ranzani, M.; Volpin, M.; Bartholomae, C.; Duros, C.; Artus, A.; Merella, S.; Benedicenti, F.; Sergi Sergi, L.; Sanvito, F.; et al. Uncovering and Dissecting the Genotoxicity of Self–Inactivating Lentiviral Vectors in Vivo. Mol. Ther. 2014, 22, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, J.A.; Ma, X.; Linders, B.; Wu, S.; Schambach, A.; Ohlemiller, K.K.; Kovacs, A.; Bigg, M.; He, L.; Tollefsen, D.M.; et al. A Self–Inactivating γ–Retroviral Vector Reduces Manifestations of Mucopolysaccharidosis i in Mice. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacein–Bey–Abina, S.; Pai, S.-Y.; Gaspar, H.B.; Armant, M.; Berry, C.C.; Blanche, S.; Bleesing, J.; Blondeau, J.; de Boer, H.; Buckland, K.F.; et al. A Modified γ–Retrovirus Vector for X–Linked Severe Combined Immunodeficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushman, F. Targeting Retroviral Integration? Science 1995, 267, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesana, D.; Sgualdino, J.; Rudilosso, L.; Merella, S.; Naldini, L.; Montini, E. Whole Transcriptome Characterization of Aberrant Splicing Events Induced by Lentiviral Vector Integrations. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavazzana–Calvo, M.; Payen, E.; Negre, O.; Wang, G.; Hehir, K.; Fusil, F.; Down, J.; Denaro, M.; Brady, T.; Westerman, K.; et al. Transfusion Independence and HMGA2 Activation after Gene Therapy of Human β–Thalassaemia. Nature 2010, 467, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suerth, J.D.; Maetzig, T.; Galla, M.; Baum, C.; Schambach, A. Self–Inactivating Alpharetroviral Vectors with a Split–Packaging Design. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 6626–6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudek, L.S.; Zimmermann, K.; Galla, M.; Meyer, J.; Kuehle, J.; Stamopoulou, A.; Brand, D.; Sandalcioglu, I.E.; Neyazi, B.; Moritz, T.; et al. Generation of an NFκB–Driven Alpharetroviral “All–in–One” Vector Construct as a Potent Tool for CAR NK Cell Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suerth, J.D.; Maetzig, T.; Brugman, M.H.; Heinz, N.; Appelt, J.U.; Kaufmann, K.B.; Schmidt, M.; Grez, M.; Modlich, U.; Baum, C.; et al. Alpharetroviral Self–Inactivating Vectors: Long–Term Transgene Expression in Murine Hematopoietic Cells and Low Genotoxicity. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labenski, V.; Suerth, J.D.; Barczak, E.; Heckl, D.; Levy, C.; Bernadin, O.; Charpentier, E.; Williams, D.A.; Fehse, B.; Verhoeyen, E.; et al. Alpharetroviral Self–Inactivating Vectors Produced by a Superinfection–Resistant Stable Packaging Cell Line Allow Genetic Modification of Primary Human T Lymphocytes. Biomaterials 2016, 97, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suerth, J.D.; Morgan, M.A.; Kloess, S.; Heckl, D.; Neudörfl, C.; Falk, C.S.; Koehl, U.; Schambach, A. Efficient Generation of Gene–Modified Human Natural Killer Cells via Alpharetroviral Vectors. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 94, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, J.; Hoseini, S.S.; Suerth, J.D.; Hoffmann, D.; Maluski, M.; Herbst, J.; Maul, H.; Ghosh, A.; Eiz–Vesper, B.; Yuan, Q.; et al. Generation of Genetically Engineered Precursor T–Cells from Human Umbilical Cord Blood Using an Optimized Alpharetroviral Vector Platform. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, Y.; Sens, J.; Lange, L.; Nassauer, L.; Klatt, D.; Hoffmann, D.; Kleppa, M.J.; Barbosa, P.V.; Keisker, M.; Steinberg, V.; et al. Improved Alpharetrovirus–Based Gag.MS2 Particles for Efficient and Transient Delivery of CRISPR–Cas9 into Target Cells. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2022, 27, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, K.B.; Brendel, C.; Suerth, J.D.; Mueller–Kuller, U.; Chen–Wichmann, L.; Schwäble, J.; Pahujani, S.; Kunkel, H.; Schambach, A.; Baum, C.; et al. Alpharetroviral Vector–Mediated Gene Therapy for X–CGD: Functional Correction and Lack of Aberrant Splicing. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 648–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, D.W.; Miller, A.D. Foamy Virus Vectors. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linial, M. Why Aren’t Foamy Viruses Pathogenic? Trends Microbiol. 2000, 8, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trobridge, G.; Josephson, N.; Vassilopoulos, G.; Mac, J.; Russell, D.W. Improved Foamy Virus Vectors with Minimal Viral Sequences. Mol. Ther. 2002, 6, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasimuzzaman, M.; Kim, Y.S.; Wang, Y.D.; Persons, D.A. High–Titer Foamy Virus Vector Transduction and Integration Sites of Human CD34+ Cell–Derived SCID–Repopulating Cells. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2014, 1, 14020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucali, J.R.; Ciccarone, T.; Kelley, V.; Park, J.; Johnson, C.M.; Mergia, A. Transduction of Umbilical Cord Blood CD34+ NOD/SCID–Repopulating Cells by Simian Foamy Virus Type 1 (SFV–1) Vector. Virology 2002, 302, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajawat, Y.S.; Humbert, O.; Kiem, H.P. In–Vivo Gene Therapy with Foamy Virus Vectors. Viruses 2019, 11, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horino, S.; Uchiyama, T.; So, T.; Nagashima, H.; Sun, S.L.; Sato, M.; Asao, A.; Haji, Y.; Sasahara, Y.; Candotti, F.; et al. Gene Therapy Model of X–Linked Severe Combined Immunodeficiency Using a Modified Foamy Virus Vector. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.R.; Tuschong, L.M.; Calvo, K.R.; Shive, H.R.; Burkholder, T.H.; Karlsson, E.K.; West, R.R.; Russell, D.W.; Hickstein, D.D. Long–Term Follow–up of Foamy Viral Vector–Mediated Gene Therapy for Canine Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 964–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Sweeney, N.P.; Doreste, B.; Muntoni, F.; McClure, M.; Morgan, J. Restoration of Functional Full–Length Dystrophin after Intramuscular Transplantation of Foamy Virus–Transduced Myoblasts. Hum. Gene Ther. 2020, 31, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilopoulos, G.; Trobridge, G.; Josephson, N.C.; Russell, D.W. Gene Transfer into Murine Hematopoietic Stem Cells with Helper–Free Foamy Virus Vectors. Blood 2001, 98, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, D.L.; Everson, E.M.; Leap, D.J.; Hocum, J.D.; Wang, H.; Stamatoyannopoulos, G.; Trobridge, G.D. Evidence for the in Vivo Safety of Insulated Foamy Viral Vectors. Gene Ther. 2017, 24, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Everson, E.M.; Olzsko, M.E.; Leap, D.J.; Hocum, J.D.; Trobridge, G.D. A Comparison of Foamy and Lentiviral Vector Genotoxicity in SCID–Repopulating Cells Shows Foamy Vectors Are Less Prone to Clonal Dominance. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2016, 3, 16048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, M.A.; Arumugam, P.; Pillis, D.M.; Loberg, A.; Nasimuzzaman, M.; Lynn, D.; van der Loo, J.C.M.; Dexheimer, P.J.; Keddache, M.; Bauer, T.R.; et al. Foamy Virus Vector Carries a Strong Insulator in Its Long Terminal Repeat Which Reduces Its Genotoxic Potential. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01639-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eversona, E.M.; Hocuma, J.D.; Trobridge, G.D. Efficacy and Safety of a Clinically Relevant Foamy Vector Design in Human Hematopoietic Repopulating Cells. J. Gene Med. 2018, 20, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.; Kindler, V.; Ducrey, O.; Chapuis, B.; Zubler, R.H.; Trono, D. High–Level Transgene Expression in Human Hematopoietic Progenitors and Differentiated Blood Lineages after Transduction with Improved Lentiviral Vectors. Blood 2000, 96, 3392–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global HIV, Hepatitis and STIs. Available online: https://www.who.int/news–room/fact–sheets/detail/hiv–aids (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Castro-Gonzalez, S.; Colomer-Lluch, M.; Serra-Moreno, R. Barriers for HIV Cure: The Latent Reservoir. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2018, 34, 739–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volberding, P.A.; Deeks, S.G. Antiretroviral Therapy and Management of HIV Infection. Lancet 2010, 376, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, C.H.; Chevalier, P. Hospital economic burden of HIV and its complications in Belgium. In Proceedings of the 5th Belgium Research on AIDS and HIV Consortium (BREACH) Symposium, Charleroi, Belgium, 25 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva Feelixge, H.S.; Stone, D.; Pietz, H.L.; Roychoudhury, P.; Greninger, A.L.; Schiffer, J.T.; Aubert, M.; Jerome, K.R. Detection of Treatment–Resistant Infectious HIV after Genome–Directed Antiviral Endonuclease Therapy. Antiviral Res. 2016, 126, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harrigan, P.R.; Hogg, R.S.; Dong, W.W.Y.; Yip, B.; Wynhoven, B.; Woodward, J.; Brumme, C.J.; Brumme, Z.L.; Mo, T.; Alexander, C.S.; et al. Predictors of HIV Drug–Resistance Mutations in a Large Antiretroviral–Naive Cohort Initiating Triple Antiretroviral Therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 191, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meresse, M.; March, L.; Kouanfack, C.; Bonono, R.C.; Boyer, S.; Laborde-Balen, G.; Aghokeng, A.; Suzan–Monti, M.; Delaporte, E.; Spire, B.; et al. Patterns of Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy and HIV Drug Resistance over Time in the Stratall ANRS 12110/ESTHER Trial in Cameroon. HIV Med. 2014, 15, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodin, J.; Zanini, F.; Thebo, L.; Lanz, C.; Bratt, G.; Neher, R.A.; Albert, J. Establishment and Stability of the Latent HIV-1 DNA Reservoir. Elife 2016, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abner, E.; Jordan, A. HIV “Shock and Kill” Therapy: In Need of Revision. Antiviral Res. 2019, 166, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielle, X.; Morales, S.E.; Grineski, T.W.C. Strategies to Target Non–T Cell HIV Reservoirs. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2016, 176, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søgaard, O.S.; Graversen, M.E.; Leth, S.; Olesen, R.; Brinkmann, C.R.; Nissen, S.K.; Kjaer, A.S.; Schleimann, M.H.; Denton, P.W.; Hey–Cunningham, W.J.; et al. The Depsipeptide Romidepsin Reverses HIV-1 Latency In Vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archin, N.M.; Liberty, A.L.; Kashuba, A.D.; Choudhary, S.K.; Kuruc, J.D.; Crooks, A.M.; Parker, D.C.; Anderson, E.M.; Kearney, M.F.; Strain, M.C.; et al. Administration of Vorinostat Disrupts HIV-1 Latency in Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy. Nature 2012, 487, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matalon, S.; Rasmussen, T.A.; Dinarello, C.A. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors for Purging HIV-1 from the Latent Reservoir. Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Martinez, J.P.; Zorita, E.; Meyerhans, A.; Filion, G.J. Position Effects Influence HIV Latency Reversal. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battivelli, E.; Dahabieh, M.S.; Abdel–Mohsen, M.; Peter Svensson, J.; da Silva, I.T.; Cohn, L.B.; Gramatica, A.; Deeks, S.; Greene, W.; Pillai, S.K.; et al. Distinct Chromatin Functional States Correlate with HIV Latency Reversal in Infected Primary CD4+ T Cells. Elife 2018, 7, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moranguinho, I.; Valente, S.T. Block–and–Lock: New Horizons for a Cure for HIV-1. Viruses 2020, 12, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansant, G.; Bruggemans, A.; Janssens, J.; Debyser, Z. Block–and–Lock Strategies to Cure HIV Infection. Viruses 2020, 12, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, M.P.; Khoury, D.S.; Cromer, D.; Lewin, S.R.; Kelleher, A.D.; Kent, S.J. Functional Cure of HIV: The Scale of the Challenge. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousseau, G.; Valente, S.T. Didehydro–Cortistatin A: A New Player in HIV–Therapy? Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2016, 14, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mediouni, S.; Chinthalapudi, K.; Ekka, M.K.; Usui, I.; Jablonski, J.A.; Clementz, M.A.; Mousseau, G.; Nowak, J.; Macherla, V.R.; Beverage, J.N.; et al. Didehydro–Cortistatin a Inhibits HIV-1 by Specifically Binding to the Unstructured Basic Region of Tat. MBio 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean, M.J.; Hayashi, T.; Huang, H.; Brennan, J.; Simpson, S.; Purmal, A.; Gurova, K.; Keefer, M.C.; Kobie, J.J.; Santoso, N.G.; et al. Curaxin CBL0100 Blocks HIV-1 Replication and Reactivation through Inhibition of Viral Transcriptional Elongation. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, J.; Parveen, A.; Rozy, F.; Mitra, A.; Bal, C.; Mitra, D.; Sharon, A. Discovery of 2–Isoxazol–3–Yl–Acetamide Analogues as Heat Shock Protein 90 (HSP90) Inhibitors with Significant Anti–HIV Activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 183, 111699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, G.; Poesen, J.; Goossens, D. Novel Mechanisms to Inhibit HIV Reservoir Seeding Using Jak Inhibitors Christina. Manag. Soil Qual. Challenges Mod. Agric. 2009, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.E.; Calantone, N.; Lichon, D.; Hudson, H.; Clerc, I.; Campbell, E.M.; D’Aquila, R.T. MTOR Overcomes Multiple Metabolic Restrictions to Enable HIV-1 Reverse Transcription and Intracellular Transport. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlenstiel, C.L.; Symonds, G.; Kent, S.J.; Kelleher, A.D. Block and Lock HIV Cure Strategies to Control the Latent Reservoir. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einkauf, K.B.; Lee, G.Q.; Gao, C.; Sharaf, R.; Sun, X.; Hua, S.; Chen, S.M.Y.; Jiang, C.; Lian, X.; Chowdhury, F.Z.; et al. Intact HIV-1 Proviruses Accumulate at Distinct Chromosomal Positions during Prolonged Antiretroviral Therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Fact Sheet Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news–room/fact–sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Kaufman, H.L.; Kohlhapp, F.J.; Zloza, A. Oncolytic Viruses: A New Class of Immunotherapy Drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 642–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gu, X.; Yu, J.; Ge, S.; Fan, X. Oncolytic Virotherapy: From Bench to Bedside. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawler, S.E.; Speranza, M.C.; Cho, C.F.; Chiocca, E.A. Oncolytic Viruses in Cancer Treatment a Review. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, C.-K.; Kasahara, N. Replication–Competent Retrovirus Vectors for Cancer Gene Therapy Chien–Kuo. Front. Biosci. 2008, 13, 3083–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, S.; Takagi–Kimura, M.; Kasahara, N. Efficient Tumor Transduction and Antitumor Efficacy in Experimental Human Osteosarcoma Using Retroviral Replicating Vectors. Cancer Gene Ther. 2019, 26, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, Y.; Tamamoto, A.; Maeyama, Y.; Yamaoka, N.; Okamura, H.; Kasahara, N.; Kubo, S.; Angeles, L. Replication–Competent Retrovirus Vector–Mediated Prodrug Activator Gene Therapy in Experimental Models of Human Malignant Mesothelioma. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012, 18, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, O.D.; Logg, C.R.; Hiraoka, K.; Diago, O.; Burnett, R.; Inagaki, A.; Jolson, D.; Amundson, K.; Buckley, T.; Lohse, D.; et al. Design and Selection of Toca 511 for Clinical Use: Modified Retroviral Replicating Vector with Improved Stability and Gene Expression. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Cancer, G.; Bueren, J.A.; Energe, C.D.I.; Cavazzana, M.; Hospital, N.; Thrasher, A.; Health, C.; Madero, L.; Galy, A.; et al. Does Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Gene Therapy Safely Improve Outcome in Severe Early–Onset Fetal Growth Restriction? (EVERREST). Hum. Gene Ther. Clin. Dev. 2015, 26, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreadis, S.T.; Brott, D.; Fuller, A.O.; Palsson, B.O. Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus–Derived Retroviral Vectors Decay Intracellularly with a Half–Life in the Range of 5.5 to 7.5 Hours. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 7541–7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzik, K.M.; Nace, R.A.; Ikeda, Y.; Russell, S.J. Oncolytic Foamy Virus: Generation and Properties of a Nonpathogenic Replicating Retroviral Vector System That Targets Chronically Proliferating Cancer Cells. J. Virol. 2021, 95, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logg, C.R.; Robbins, J.M.; Jolly, D.J.; Gruber, H.E.; Kasahara, N. Retroviral replicating vectors in cancer. Methods Enzym. 2012, 507, 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzik, K.M.; Nace, R.A.; Ikeda, Y.; Russell, S.J. Evaluation of the Stability and Intratumoral Delivery of Foreign Transgenes Encoded by an Oncolytic Foamy Virus Vector. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022, 29, 1240–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzon, M.J.; Martin–Gayo, E.; Pereyra, F.; Ouyang, Z.; Sun, H.; Li, J.Z.; Piovoso, M.; Shaw, A.; Dalmau, J.; Zangger, N.; et al. Long–Term Antiretroviral Treatment Initiated at Primary HIV-1 Infection Affects the Size, Composition, and Decay Kinetics of the Reservoir of HIV-1 –Infected CD4 T Cells. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 10056–10065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, M.; Joseph, S.B.; Garrett, N.; Tyers, L.; Archin, N.; Council, O.D.; Matten, D.; Zhou, S.; Anthony, C.; Goonetilleke, N.; et al. The Replication–Competent HIV-1 Latent Reservoir Is Primarily Established Near the Time of Therapy Initiation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 11, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Host Factors and Viral Proteins Involved in Nuclear Import and/or MLV Integration Site Selection | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Host Factor | Viral Protein | Description | References |

| p12 | / | Tether of PIC to mitotic chromosomes | [46,47,48,49,50] |

| BET | / | BD binds viral IN, ET binds chromatin | [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] |

| / | IN | CCD and CTD bind target DNA | [30,51,53,58,59] |

| Host Factors and Viral Proteins Involved in Nuclear Import and/or HIV-1 Integration Site Selection | |||

| Host Factor | Viral Protein | Description | References |

| TRN–SR2 | / | Karyopherin involved in nuclear import | [60] |

| RanBP2 | / | Nuclear pore protein involved in Nuclear import | [60] |

| Nup153 | / | Karyopherin involved in nuclear import | [61,62] |

| CPSF6 | / | Nuclear import factor binding to HIV-1 capsid | [63,64,65,66,67] |

| LEDGF/p75 | / | IBD binds viral IN, PWWP domain binds H3K36me2/3 | [22,23,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,45,52,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87] |

| HRP2 | / | IBD binds viral IN, PWWP domain binds H3K36me2/3 | [74] |

| / | IN | CCD and CTD bind target DNA | [88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98] |

| Retroviral Integration Site Selection | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrovirus | Classification | Classification | Host Factor | Viral Protein | References |

| ASLV | ortho-retroverinae | alpharetrovirus | Unknown (FACT complex?) | / | [5,6,7,99,100,101] |

| RSV | alpharetrovirus | Unknown (FACT complex?) | IN | [8,102,103,104,105] | |

| MMTV | betaretrovirus | / | / | [9,10,11,106,107,108] | |

| MLV | gammaretrovirus | BET proteins | IN | see Table 1 | |

| HTLV-1 | deltaretrovirus | PP2A | / | [13,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120] | |

| HTLV-2 | deltaretrovirus | PP2A | / | [14,120] | |

| BLV | deltaretrovirus | PP2A | / | [15,16,17,18,19,121] | |

| HIV-1 | lentiretrovirus | LEDGF/p75 | IN | see Table 1 | |

| HIV-2 | Lentiretrovirus | LEDGF/p75 | / | [122,123,124,125,126,127] | |

| SIV | Lentiretrovirus | LEDGF/p75 | IN | [24,128,129] | |

| FIV | lentiretrovirus | LEDGF/p75 | / | [25,37] | |

| Humanfoamy virus | Spuma-retrovirinae | / | Gag | [26,27,49,130,131,132,133] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pellaers, E.; Bhat, A.; Christ, F.; Debyser, Z. Determinants of Retroviral Integration and Implications for Gene Therapeutic MLV—Based Vectors and for a Cure for HIV-1 Infection. Viruses 2023, 15, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15010032

Pellaers E, Bhat A, Christ F, Debyser Z. Determinants of Retroviral Integration and Implications for Gene Therapeutic MLV—Based Vectors and for a Cure for HIV-1 Infection. Viruses. 2023; 15(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15010032

Chicago/Turabian StylePellaers, Eline, Anayat Bhat, Frauke Christ, and Zeger Debyser. 2023. "Determinants of Retroviral Integration and Implications for Gene Therapeutic MLV—Based Vectors and for a Cure for HIV-1 Infection" Viruses 15, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15010032

APA StylePellaers, E., Bhat, A., Christ, F., & Debyser, Z. (2023). Determinants of Retroviral Integration and Implications for Gene Therapeutic MLV—Based Vectors and for a Cure for HIV-1 Infection. Viruses, 15(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15010032