Comparisons of Viral Etiology and Outcomes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Undergoing Liver Resection between Taiwan and Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Differences in Age and Gender According to Viral Etiology of HCC

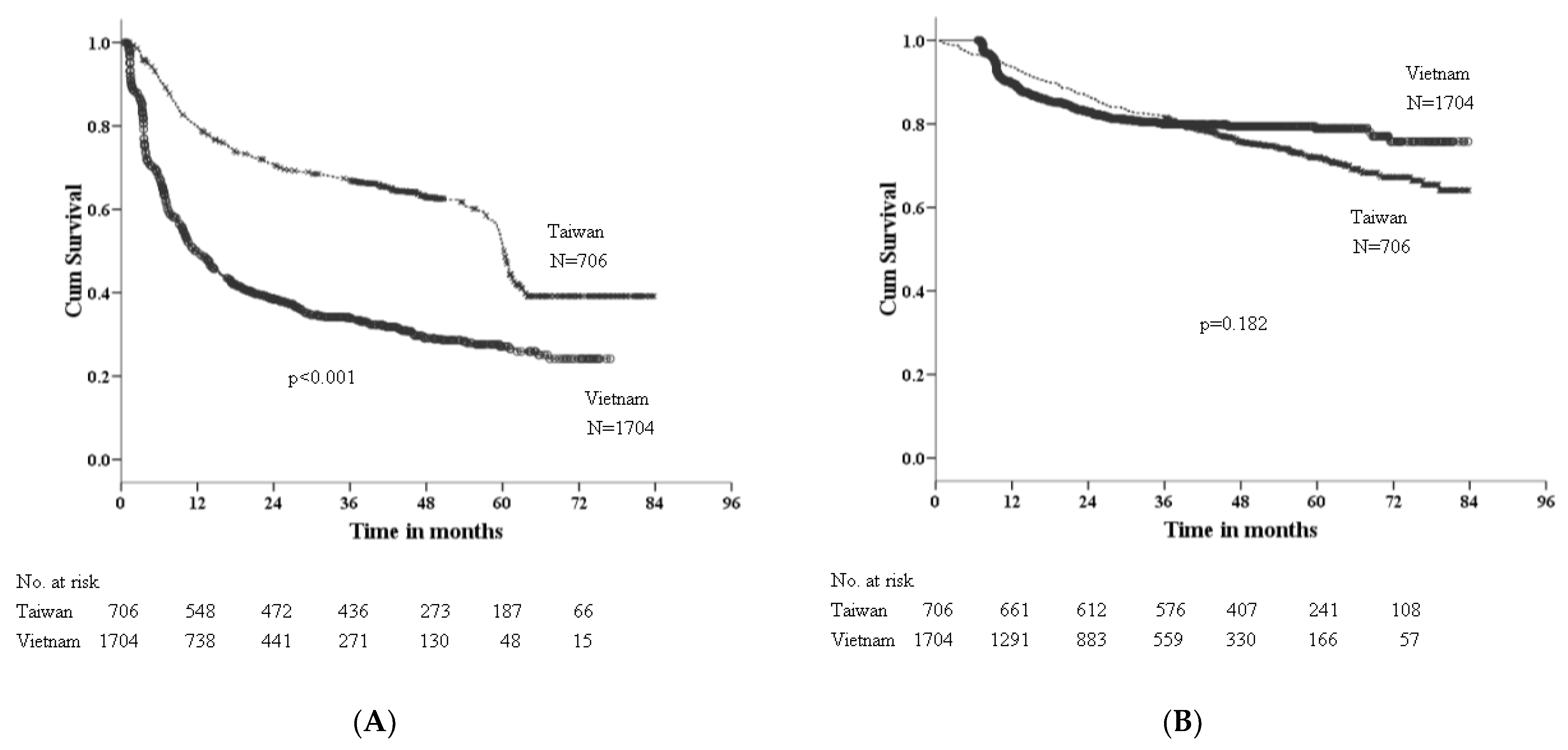

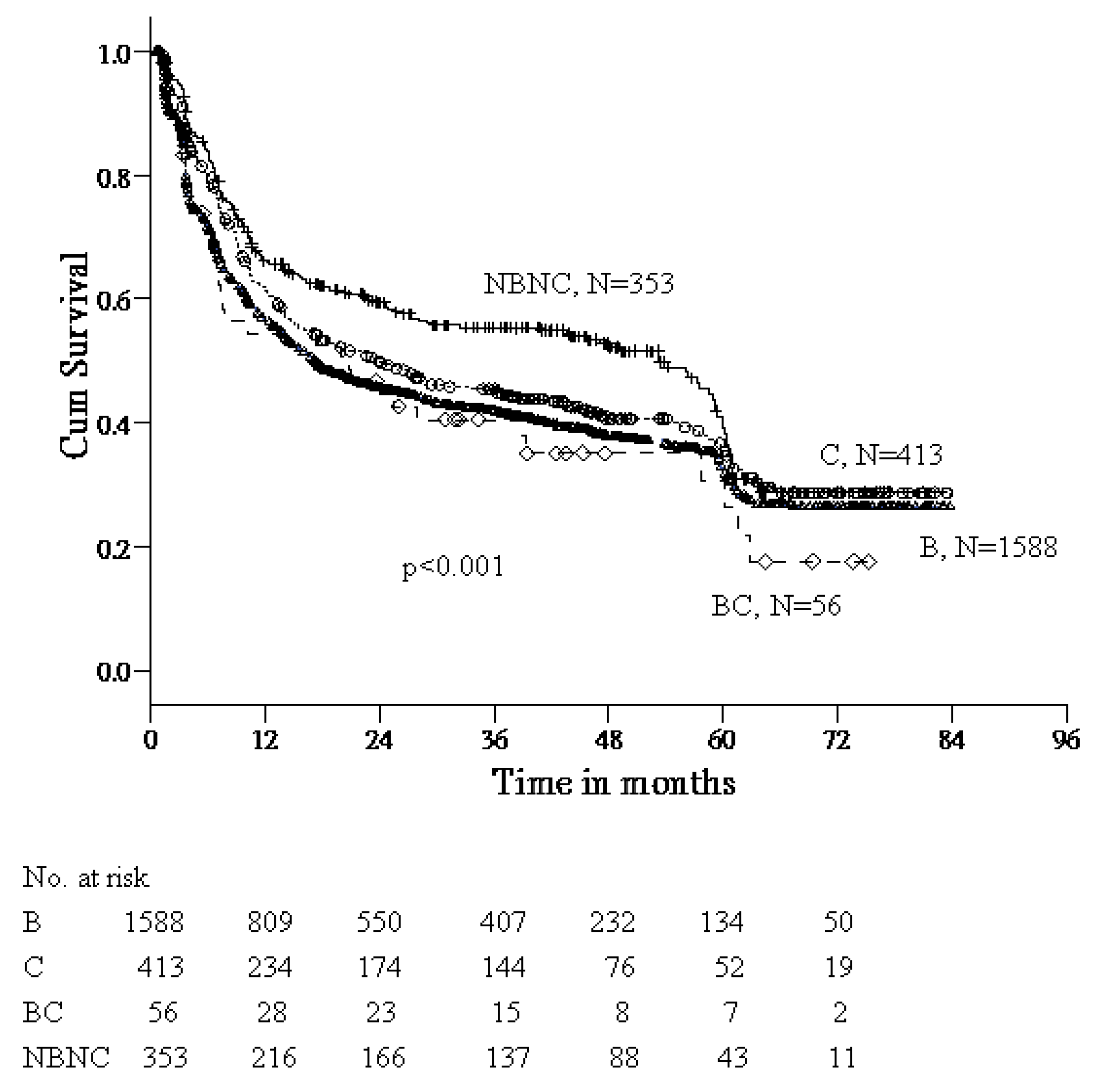

3.3. Factors Associated with RFS

3.4. Factors Associated with OS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Llovet, J.M.; Kelley, R.K.; Villanueva, A.; Singal, A.G.; Pikarsky, E.; Roayaie, S.; Lencioni, R.; Koike, K.; Zucman-Rossi, J.; Finn, R.S. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2021, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: Easloffice@easloffice.eu; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 182–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGlynn, K.A.; Petrick, J.L.; El-Serag, H.B. Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology 2021, 73, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, F.P.; Zanetto, A.; Pinto, E.; Battistella, S.; Penzo, B.; Burra, P.; Farinati, F. Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Viral Hepatitis: Where Do We Stand? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetto, A.; Shalaby, S.; Gambato, M.; Germani, G.; Senzolo, M.; Bizzaro, D.; Russo, F.P.; Burra, P. New Indications for Liver. Transplantation. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anstee, Q.M.; Reeves, H.L.; Kotsiliti, E.; Govaere, O.; Heikenwalder, M. From NASH to HCC: Current concepts and future challenges. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.D.; Hainaut, P.; Gores, G.J.; Amadou, A.; Plymoth, A.; Roberts, L.R. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: Trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.X.; Seto, W.K.; Lai, C.L.; Yuen, M.F. Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Asia-Pacific Region. Gut Liver 2016, 10, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereno, L.; Mesquita, F.; Kato, M.; Jacka, D.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, T.N. Epidemiology, responses, and way forward: The silent epidemic of viral hepatitis and HIV coinfection in Vietnam. J. Int. Assoc. Physicians AIDS Care 2012, 11, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Law, M.G.; Dore, G.J. An enormous hepatitis B virus related liver disease burden projected in Vietnam by 2025. Liver Int. 2008, 28, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omata, M.; Cheng, A.L.; Kokudo, N.; Kudo, M.; Lee, J.M.; Jia, J.; Tateishi, R.; Han, K.H.; Chawla, Y.K.; Shiina, S.; et al. Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: A 2017 update. Hepatol. Int. 2017, 11, 317–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Changchien, C.S.; Chen, C.L.; Yen, Y.H.; Wang, J.H.; Hu, T.H.; Lee, C.M.; Wang, C.C.; Cheng, Y.F.; Huang, Y.J.; Lin, C.Y.; et al. Analysis of 6381 hepatocellular carcinoma patients in southern Taiwan: Prognostic features, treatment outcome, and survival. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 43, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.N.; Su, W.W.; Yang, S.S.; Chang, T.T.; Cheng, K.S.; Wu, J.C.; Lin, H.H.; Wu, S.S.; Lee, C.M.; Changchien, C.S.; et al. Secular trends and geographic variations of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 119, 1946–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen-Dinh, S.H.; Do, A.; Pham, T.N.D.; Dao, D.Y.; Nguy, T.N.; Chen, M.S., Jr. High burden of hepatocellular carcinoma and viral hepatitis in Southern and Central Vietnam: Experience of a large tertiary referral center, 2010 to 2016. World J. Hepatol. 2018, 10, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag, H.B. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordier, S.; Le, T.B.; Verger, P.; Bard, D.; Le, C.D.; Larouze, B.; Dazza, M.C.; Hoang, T.Q.; Abenhaim, L. Viral infections and chemical exposures as risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in Vietnam. Int. J. Cancer 1993, 55, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Lindahl, J.; Nguyen, V.H.; Khong, N.V.; Nghia, V.B.; Xuan, H.N.; Grace, D. An investigation into aflatoxin M1 in slaughtered fattening pigs and awareness of aflatoxins in Vietnam. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.T.; Liang, X.M.; Liang, G.L.; Tang, S.T.; Huo, R.R.; Ma, L.; Xiang, B.B.; et al. Analysis of Clinicopathological Characteristics and Prognosis of Young Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Hepatectomy. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2020, 8, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, S.; Kamiyama, T.; Orimo, T.; Nagatsu, A.; Asahi, Y.; Sakamoto, Y.; Kamachi, H.; Taketomi, A. Prognoses, outcomes, and clinicopathological characteristics of very elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent hepatectomy. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 18, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cescon, M.; Cucchetti, A.; Grazi, G.L.; Ferrero, A.; Viganò, L.; Ercolani, G.; Ravaioli, M.; Zanello, M.; Andreone, P.; Capussotti, L.; et al. Role of hepatitis B virus infection in the prognosis after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: A Western dual-center experience. Arch. Surg. 2009, 144, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tanase, A.M.; Dumitrascu, T.; Dima, S.; Grigorie, R.; Marchio, A.; Pineau, P.; Popescu, I. Influence of hepatitis viruses on clinicopathological profiles and long-term outcome in patients undergoing surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2014, 13, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.D.; Liang, L.; Li, C.; Wu, H.; Wang, H.; Liang, Y.J.; Zhou, Y.H.; Gu, W.M.; Fan, X.P.; Zhang, W.G.; et al. Long-Term Surgical Outcomes of Liver Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With HBV and HCV Co-Infection: A Multicenter Observational Study. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 700228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granito, A.; Muratori, L.; Lalanne, C.; Quarneti, C.; Ferri, S.; Guidi, M.; Lenzi, M.; Muratori, P. Hepatocellular carcinoma in viral and autoimmune liver diseases: Role of CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in the immune microenvironment. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 2994–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabibbo, G.; Petta, S.; Barbàra, M.; Missale, G.; Virdone, R.; Caturelli, E.; Piscaglia, F.; Morisco, F.; Colecchia, A.; Farinati, F.; et al. A meta-analysis of single HCV-untreated arm of studies evaluating outcomes after curative treatments of HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2017, 37, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garuti, F.; Neri, A.; Avanzato, F.; Gramenzi, A.; Rampoldi, D.; Rucci, P.; Farinati, F.; Giannini, E.G.; Piscaglia, F.; Rapaccini, G.L.; et al. The changing scenario of hepatocellular carcinoma in Italy: An update. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Taiwan | Vietnam | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 706 | 1704 | |||

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 548 | (77.6) | 1433 | (84.1) | |

| Female | 158 | (22.4) | 271 | (15.9) | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||

| <60 | 289 | (40.9) | 1064 | (62.4) | |

| ≥60 | 417 | (59.1) | 640 | (37.6) | |

| Mean (SD) | 60.9 | (11.0) | 54.6 | (12.3) | |

| Viral hepatitis | <0.001 | ||||

| HBV | 342 | (48.4) | 1246 | (73.1) | |

| HCV | 197 | (27.9) | 216 | (12.7) | |

| HBV/HCV | 20 | (2.8) | 36 | (2.1) | |

| Non HBV/HCV | 147 | (20.8) | 206 | (12.1) | |

| Alpha-fetoprotein (ng/mL) | <0.001 | ||||

| <400 | 567 | (80.3) | 931 | (54.6) | |

| ≥400 | 138 | (19.7) | 773 | (45.4) | |

| Mean (SD) | 4653 | (30,824) | 13,093 | (54,535) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | <0.001 | ||||

| <5 | 469 | (66.4) | 394 | (23.1) | |

| ≥5 | 237 | (33.6) | 1310 | (76.9) | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.9 | (3.8) | 7.2 | (3.7) | |

| Tumor number | <0.001 | ||||

| Single | 487 | (72.7) | 1457 | (85.5) | |

| Multiple | 183 | (27.3) | 247 | (14.5) | |

| Macrovascular invasion | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 644 | (96.1) | 1532 | (90.0) | |

| Yes | 26 | (3.9) | 172 | (10.0) | |

| Extrahepatic metastasis | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 663 | (99.0) | 1644 | (96.5) | |

| Yes | 7 | (1.0) | 60 | (3.5) | |

| HBV | HCV | B + C | NBNC | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taiwan | |||||

| Case no. | 342 | 197 | 20 | 147 | |

| Age (years) * | 57.5 ± 11.3 acf | 65.3 ± 8.3 ad | 59.5 ± 9.1 d | 63.1 ± 11.4 ch | <0.001 |

| Gender (M/F) | 287/55 (5.2) a | 126/71 (1.8) aeg | 17/3 (5.7) | 118/29 (4.1) e | <0.001 |

| Vietnam | |||||

| Case no. | 1246 | 216 | 36 | 206 | |

| Age (years) * | 52.0 ± 11.8 acf | 65.2 ± 7.5 ad | 56.8 ± 13.1 d | 59.0 ± 11.8 ch | <0.001 |

| Gender (M/F) | 1057/189 (5.6) | 175/41 (4.3) g | 33/3 (11) | 168/38 (4.4) | 0.206 |

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | aHR (95% CI) * | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Taiwan | Reference | Reference | ||

| Vietnam | 2.44 (2.15–2.77) | 2.06 (1.79–2.37) | ||

| Sex | 0.015 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||

| Male | 1.38 (1.20–1.60) | 1.37 (1.17–1.59) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.003 | |||

| <60 | Reference | |||

| ≥60 | 0.86 (0.77–0.95) | |||

| HBsAg | <0.001 | |||

| Positive | 1.26 (1.12–1.41) | |||

| Negative | Reference | |||

| Anti-HCV | 0.509 | |||

| Positive | 0.96 (0.84–1.09) | |||

| Negative | Reference | |||

| Alpha-fetoprotein (ng/mL) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| <400 | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥400 | 1.82 (1.63–2.02) | 1.44 (1.29–1.61) | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| <5 | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥5 | 1.98 (1.76–2.22) | 1.37 (1.21–1.55) | ||

| Tumor number | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Single | Reference | Reference | ||

| Multiple | 1.37 (1.20–1.56) | 1.45 (1.27–1.67) | ||

| Macrovascular invasion | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.82 (2.38–3.33) | 2.17 (1.83–2.57) | ||

| Extrahepatic metastasis | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.85 (2.17–3.75) | 2.20 (1.67–2.90) |

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | aHR (95% CI) * | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | 0.182 | |||

| Taiwan | Reference | |||

| Vietnam | 0.88 (0.73–1.06) | |||

| Sex | 0.015 | 0.012 | ||

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||

| Male | 1.37 (1.06–1.76) | 1.39 (1.08–1.81) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.652 | |||

| <60 | Reference | |||

| ≥60 | 1.04 (0.87–1.25) | |||

| HBsAg | 0.847 | |||

| Positive | 0.98 (0.81–1.18) | |||

| Negative | Reference | |||

| Anti-HCV | 0.711 | |||

| Positive | 0.96 (0.77–1.20) | |||

| Negative | Reference | |||

| Alpha-fetoprotein (ng/mL) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| <400 | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥400 | 1.87 (1.56–2.24) | 1.60 (1.32–1.93) | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| <5 | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥5 | 1.72 (1.41–2.10) | 1.40 (1.14–1.72) | ||

| Tumor number | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Single | Reference | Reference | ||

| Multiple | 2.08 (1.69–2.56) | 1.79 (1.45–2.17) | ||

| Macrovascular invasion | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 3.79 (2.96–4.84) | 2.81 (2.18–3.62) | ||

| Extrahepatic metastasis | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 3.62 (2.45–5.35) | 2.70 (1.82–4.01) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen-Dinh, S.-H.; Li, W.-F.; Liu, Y.-W.; Wang, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Wang, J.-H.; Hung, C.-H. Comparisons of Viral Etiology and Outcomes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Undergoing Liver Resection between Taiwan and Vietnam. Viruses 2022, 14, 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14112571

Nguyen-Dinh S-H, Li W-F, Liu Y-W, Wang C-C, Chen Y-H, Wang J-H, Hung C-H. Comparisons of Viral Etiology and Outcomes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Undergoing Liver Resection between Taiwan and Vietnam. Viruses. 2022; 14(11):2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14112571

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen-Dinh, Song-Huy, Wei-Feng Li, Yueh-Wei Liu, Chih-Chi Wang, Yen-Hao Chen, Jing-Houng Wang, and Chao-Hung Hung. 2022. "Comparisons of Viral Etiology and Outcomes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Undergoing Liver Resection between Taiwan and Vietnam" Viruses 14, no. 11: 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14112571

APA StyleNguyen-Dinh, S.-H., Li, W.-F., Liu, Y.-W., Wang, C.-C., Chen, Y.-H., Wang, J.-H., & Hung, C.-H. (2022). Comparisons of Viral Etiology and Outcomes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Undergoing Liver Resection between Taiwan and Vietnam. Viruses, 14(11), 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14112571