Heterogeneity and Architecture of Pathological Prion Protein Assemblies: Time to Revisit the Molecular Basis of the Prion Replication Process?

Abstract

1. Introduction

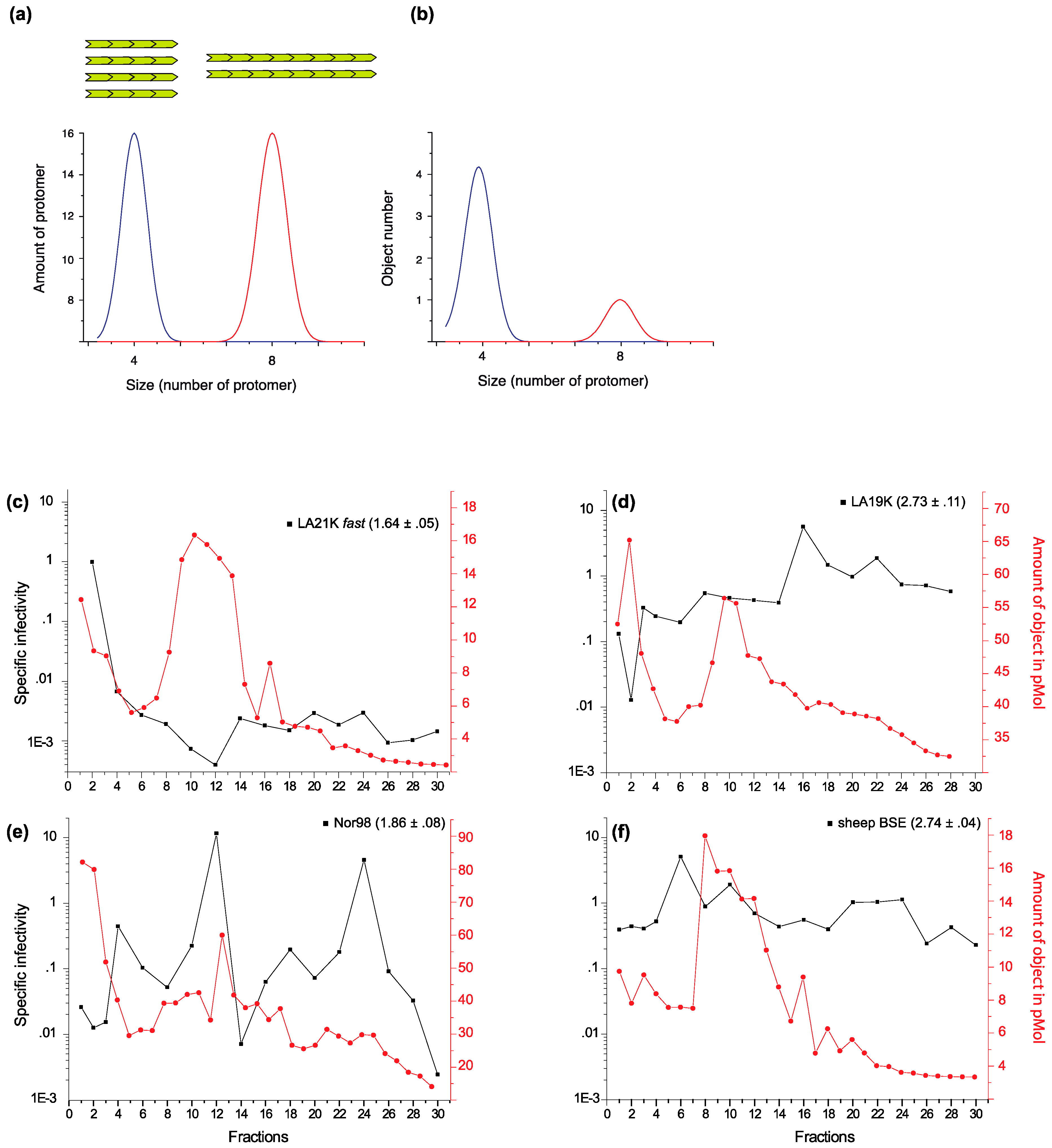

2. Strain-Dependent, Size-to-Infectivity Landscape of PrPSc Assemblies: Prions Are a Collection of Structurally Heterogeneous PrPSc Assemblies

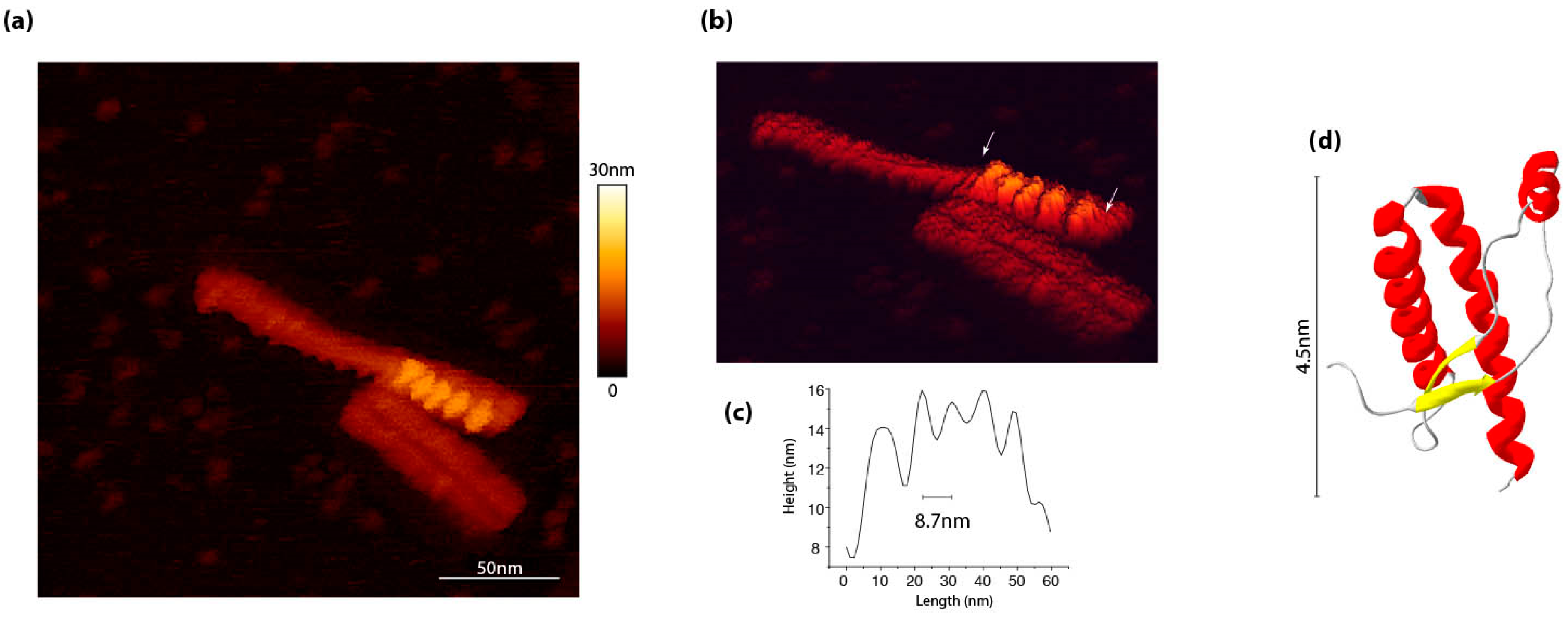

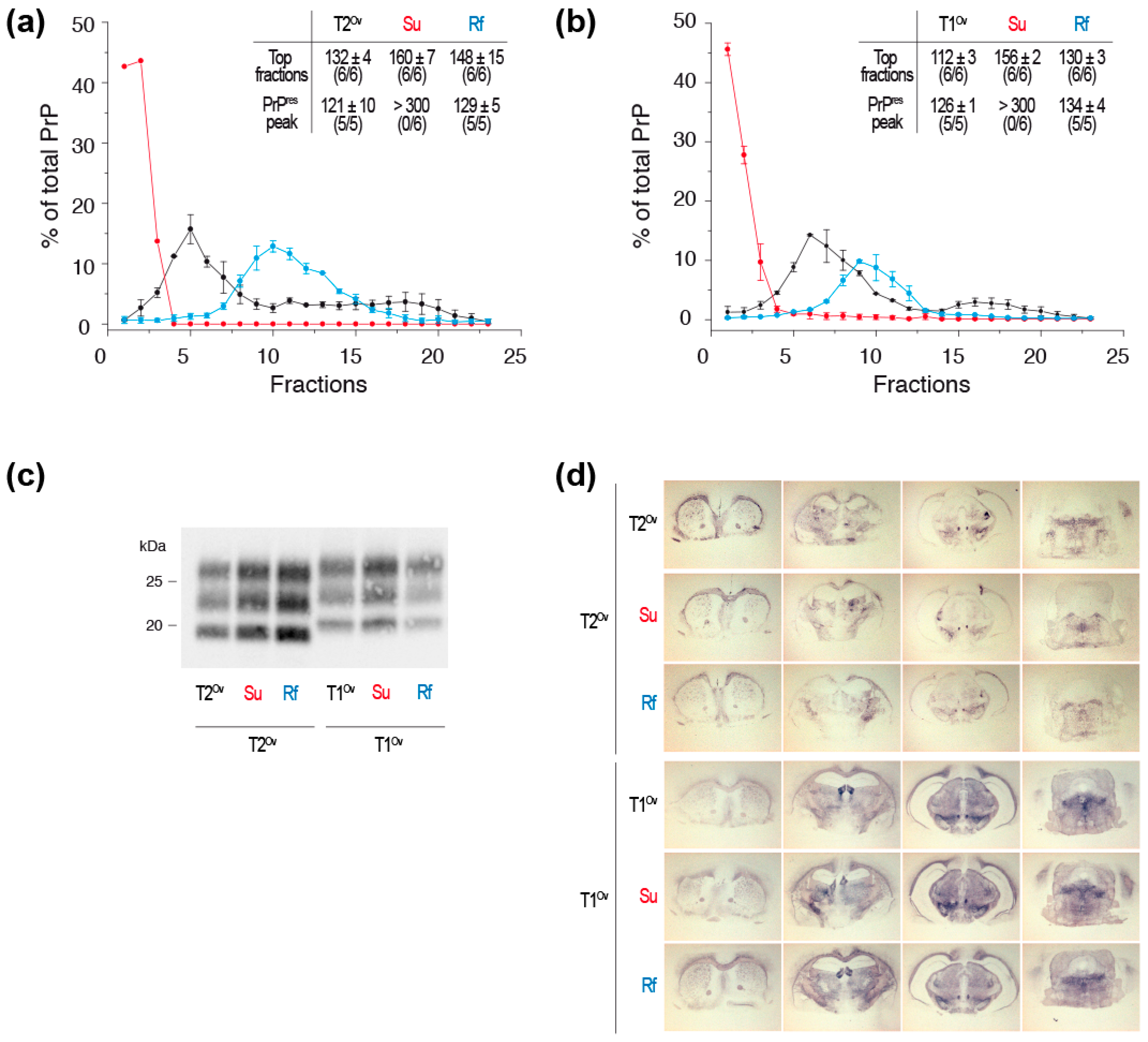

3. PrPSc Assemblies Are in a Constitutional Dynamic Equilibrium with Their Elementary Subunit

4. Time to Revisit the Molecular Basis of the Prion Replication Process?

4.1. Prion Replication Process

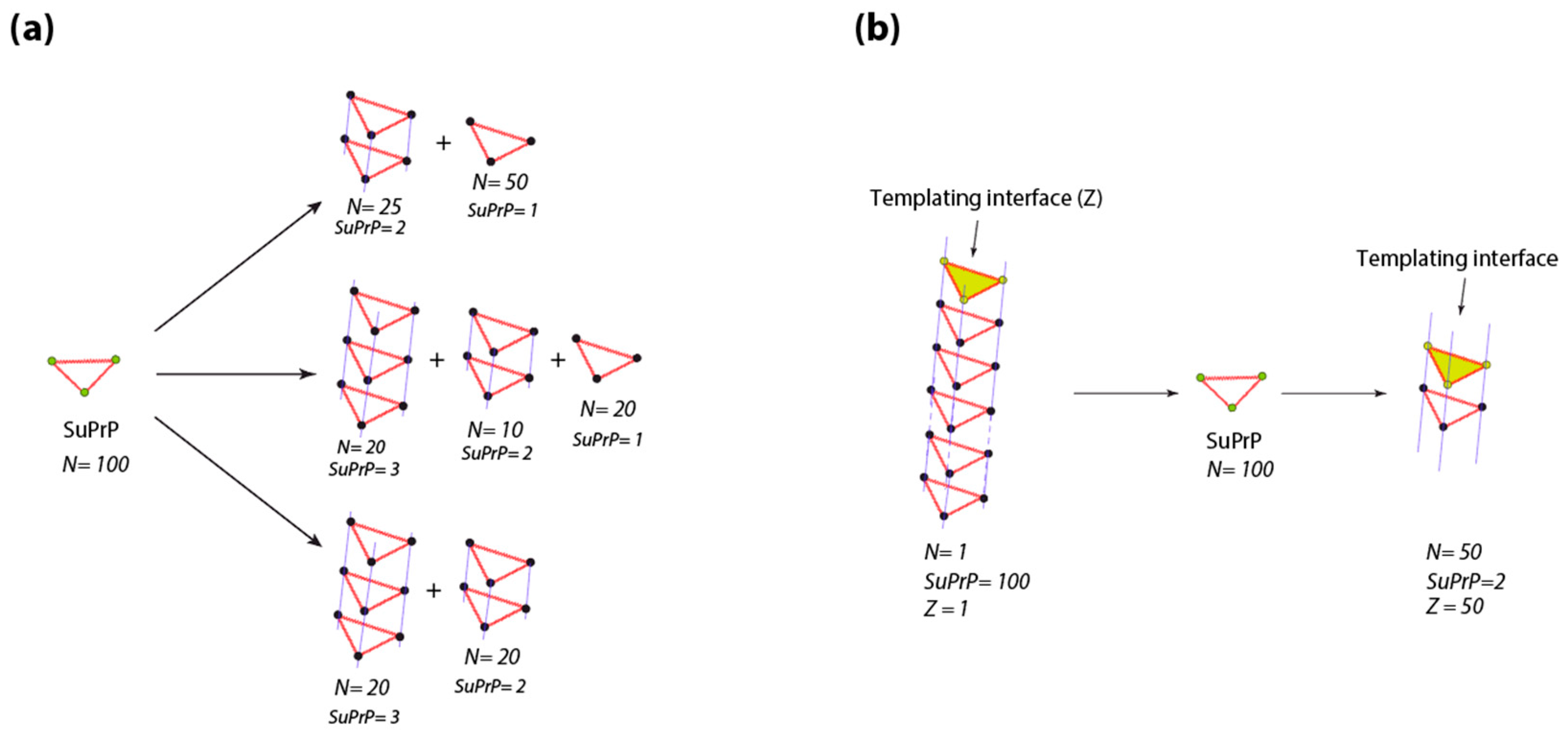

4.2. Prion Propagon

4.3. Prion Replication Process and Generation of PrPSc Assemblies Heterogeneity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collinge, J. Prion diseases of humans and animals: Their causes and molecular basis. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 24, 519–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prusiner, S.B. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science 1982, 216, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colby, D.W.; Prusiner, S.B. Prions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol. 2011, 3, a006833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beringue, V.; Vilotte, J.L.; Laude, H. Prion agent diversity and species barrier. Vet. Res. 2008, 39, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, M.E. Tse strain variation. Br. Med. Bull. 2003, 66, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinge, J.; Clarke, A.R. A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity. Science 2007, 318, 930–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissmann, C.; Li, J.; Mahal, S.P.; Browning, S. Prions on the move. EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapuis, J.; Moudjou, M.; Reine, F.; Herzog, L.; Jaumain, E.; Chapuis, C.; Quadrio, I.; Boulliat, J.; Perret-Liaudet, A.; Dron, M.; et al. Emergence of two prion subtypes in ovine prp transgenic mice infected with human mm2-cortical creutzfeldt-jakob disease prions. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2016, 4, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Dur, A.; Beringue, V.; Andreoletti, O.; Reine, F.; Lai, T.L.; Baron, T.; Bratberg, B.; Vilotte, J.L.; Sarradin, P.; Benestad, S.L.; et al. A newly identified type of scrapie agent can naturally infect sheep with resistant prp genotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16031–16036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angers, R.C.; Kang, H.E.; Napier, D.; Browning, S.; Seward, T.; Mathiason, C.; Balachandran, A.; McKenzie, D.; Castilla, J.; Soto, C.; et al. Prion strain mutation determined by prion protein conformational compatibility and primary structure. Science 2010, 328, 1154–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Browning, S.; Mahal, S.P.; Oelschlegel, A.M.; Weissmann, C. Darwinian evolution of prions in cell culture. Science 2010, 327, 869–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoneau, S.; Rezaei, H.; Sales, N.; Kaiser-Schulz, G.; Lefebvre-Roque, M.; Vidal, C.; Fournier, J.G.; Comte, J.; Wopfner, F.; Grosclaude, J.; et al. In vitro and in vivo neurotoxicity of prion protein oligomers. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3, e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg, M.K.; Al-Doujaily, H.; Sharps, B.; Clarke, A.R.; Collinge, J. Prion propagation and toxicity in vivo occur in two distinct mechanistic phases. Nature 2011, 470, 540–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg, M.K.; Al-Doujaily, H.; Sharps, B.; De Oliveira, M.W.; Schmidt, C.; Richard-Londt, A.; Lyall, S.; Linehan, J.M.; Brandner, S.; Wadsworth, J.D.; et al. Prion neuropathology follows the accumulation of alternate prion protein isoforms after infective titre has peaked. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eghiaian, F. Structuring the puzzle of prion propagation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2005, 15, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iadanza, M.G.; Jackson, M.P.; Hewitt, E.W.; Ranson, N.A.; Radford, S.E. A new era for understanding amyloid structures and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2018, 19, 755–773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wille, H.; Bian, W.; McDonald, M.; Kendall, A.; Colby, D.W.; Bloch, L.; Ollesch, J.; Borovinskiy, A.L.; Cohen, F.E.; Prusiner, S.B.; et al. Natural and synthetic prion structure from x-ray fiber diffraction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 16990–16995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakroun, N.; Prigent, S.; Dreiss, C.A.; Noinville, S.; Chapuis, C.; Fraternali, F.; Rezaei, H. The oligomerization properties of prion protein are restricted to the h2h3 domain. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 3222–3231. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, C.; Wenborn, A.; Gros, N.; Sells, J.; Joiner, S.; Hosszu, L.L.; Tattum, M.H.; Panico, S.; Clare, D.K.; Collinge, J.; et al. Ex vivo mammalian prions are formed of paired double helical prion protein fibrils. Open Biol. 2016, 6, 160035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Espinoza, R.; Soto, C. High-resolution structure of infectious prion protein: The final frontier. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012, 19, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.A.; Jiang, L.; Eisenberg, D.S. Toward the atomic structure of prp(sc). Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol. 2017, 9, a031336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wille, H.; Requena, J.R. The structure of prp(sc) prions. Pathogens 2018, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laferriere, F.; Tixador, P.; Moudjou, M.; Chapuis, J.; Sibille, P.; Herzog, L.; Reine, F.; Jaumain, E.; Laude, H.; Rezaei, H.; et al. Quaternary structure of pathological prion protein as a determining factor of strain-specific prion replication dynamics. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira, J.R.; Raymond, G.J.; Hughson, A.G.; Race, R.E.; Sim, V.L.; Hayes, S.F.; Caughey, B. The most infectious prion protein particles. Nature 2005, 437, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tixador, P.; Herzog, L.; Reine, F.; Jaumain, E.; Chapuis, J.; Le Dur, A.; Laude, H.; Beringue, V. The physical relationship between infectivity and prion protein aggregates is strain-dependent. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Haldiman, T.; Surewicz, K.; Cohen, Y.; Chen, W.; Blevins, J.; Sy, M.S.; Cohen, M.; Kong, Q.; Telling, G.C.; et al. Small protease sensitive oligomers of prp(sc) in distinct human prions determine conversion rate of prp(c). PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzaban, S.; Friedlander, G.; Schonberger, O.; Horonchik, L.; Yedidia, Y.; Shaked, G.; Gabizon, R.; Taraboulos, A. Protease-sensitive scrapie prion protein in aggregates of heterogeneous sizes. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 12868–12875. [Google Scholar]

- Bett, C.; Joshi-Barr, S.; Lucero, M.; Trejo, M.; Liberski, P.; Kelly, J.W.; Masliah, E.; Sigurdson, C.J. Biochemical properties of highly neuroinvasive prion strains. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bett, C.; Lawrence, J.; Kurt, T.D.; Orru, C.; Aguilar-Calvo, P.; Kincaid, A.E.; Surewicz, W.K.; Caughey, B.; Wu, C.; Sigurdson, C.J. Enhanced neuroinvasion by smaller, soluble prions. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2017, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajnani, G.; Silva, C.J.; Ramos, A.; Pastrana, M.A.; Onisko, B.C.; Erickson, M.L.; Antaki, E.M.; Dynin, I.; Vazquez-Fernandez, E.; Sigurdson, C.J.; et al. Pk-sensitive prp is infectious and shares basic structural features with pk-resistant prp. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastrana, M.A.; Sajnani, G.; Onisko, B.; Castilla, J.; Morales, R.; Soto, C.; Requena, J.R. Isolation and characterization of a proteinase k-sensitive prpsc fraction. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 15710–15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, T.; Li, R.; Kang, S.C.; Pastore, M.; Wong, B.S.; Ironside, J.; Gambetti, P.; Sy, M.S. Biochemical fingerprints of prion diseases: Scrapie prion protein in human prion diseases that share prion genotype and type. J. Neurochem. 2005, 92, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riesner, D.; Kellings, K.; Post, K.; Wille, H.; Serban, H.; Groth, D.; Baldwin, M.A.; Prusiner, S.B. Disruption of prion rods generates 10-nm spherical particles having high alpha-helical content and lacking scrapie infectivity. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 1714–1722. [Google Scholar]

- Alper, T.; Haig, D.A.; Clarke, M.C. The exceptionally small size of the scrapie agent. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1966, 22, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, E.J.; Farmer, F.; Caspary, E.A.; Joyce, G. Susceptibility of scrapie agent to ionizing radiation. Nature 1969, 222, 90–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latarjet, R.; Muel, B.; Haig, D.A.; Clarke, M.C.; Alper, T. Inactivation of the scrapie agent by near monochromatic ultraviolet light. Nature 1970, 227, 1341–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinger-Kawahara, C.G.; Kempner, E.; Groth, D.; Gabizon, R.; Prusiner, S.B. Scrapie prion liposomes and rods exhibit target sizes of 55,000 da. Virology 1988, 164, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronier, S.; Gros, N.; Tattum, M.H.; Jackson, G.S.; Clarke, A.R.; Collinge, J.; Wadsworth, J.D. Detection and characterization of proteinase k-sensitive disease-related prion protein with thermolysin. Biochem. J. 2008, 416, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, Y.; Kraineva, J.; Ravindra, R.; Lima, L.M.; Gomes, M.P.; Foguel, D.; Winter, R.; Silva, J.L. Hydration and packing effects on prion folding and beta-sheet conversion. High pressure spectroscopy and pressure perturbation calorimetry studies. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 32354–32359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, A.; Dodson, G.G.; Verma, C.S.; Zagari, A.; Fraternali, F. Prion and water: Tight and dynamical hydration sites have a key role in structural stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 7535–7540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.L.; Vieira, T.C.; Gomes, M.P.; Bom, A.P.; Lima, L.M.; Freitas, M.S.; Ishimaru, D.; Cordeiro, Y.; Foguel, D. Ligand binding and hydration in protein misfolding: Insights from studies of prion and p53 tumor suppressor proteins. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrent, J.; Lange, R.; Rezaei, H. The volumetric diversity of misfolded prion protein oligomers revealed by pressure dissociation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 20417–20426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimberlin, R.H.; Millson, G.C.; Hunter, G.D. An experimental examination of the scrapie agent in cell membrane mixtures. 3. Studies of the operational size. J. Comp. Pathol. 1971, 81, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siakotos, A.N.; Gajdusek, D.C.; Gibbs, C.J., Jr.; Traub, R.D.; Bucana, C. Partial purification of the scrapie agent from mouse brain by pressure disruption and zonal centrifugation in sucrose-sodium chloride gradients. Virology 1976, 70, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, T.G.; Marsh, R.F.; Hanson, R.P.; Semancik, J.S. Membrane-free scrapie activity. J. Virol. 1978, 25, 933–935. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morales, R.; Hu, P.P.; Duran-Aniotz, C.; Moda, F.; Diaz-Espinoza, R.; Chen, B.; Bravo-Alegria, J.; Makarava, N.; Baskakov, I.V.; Soto, C. Strain-dependent profile of misfolded prion protein aggregates. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, J.S. Self-replication and scrapie. Nature 1967, 215, 1043–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansbury, P.T., Jr.; Caughey, B. The chemistry of scrapie infection: Implications of the ‘ice 9’ metaphor. Chem. Biol. 1995, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Fernandez, E.; Vos, M.R.; Afanasyev, P.; Cebey, L.; Sevillano, A.M.; Vidal, E.; Rosa, I.; Renault, L.; Ramos, A.; Peters, P.J.; et al. The structural architecture of an infectious mammalian prion using electron cryomicroscopy. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweckstetter, M.; Requena, J.R.; Wille, H. Elucidating the structure of an infectious protein. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMarco, M.L.; Daggett, V. From conversion to aggregation: Protofibril formation of the prion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 2293–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenborn, A.; Terry, C.; Gros, N.; Joiner, S.; D’Castro, L.; Panico, S.; Sells, J.; Cronier, S.; Linehan, J.M.; Brandner, S.; et al. A novel and rapid method for obtaining high titre intact prion strains from mammalian brain. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igel-Egalon, A.; Moudjou, M.; Martin, D.; Busley, A.; Knapple, T.; Herzog, L.; Reine, F.; Lepejova, N.; Richard, C.A.; Beringue, V.; et al. Reversible unfolding of infectious prion assemblies reveals the existence of an oligomeric elementary brick. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, N.J.; Sonnichsen, F.D.; McHaourab, H.; Surewicz, W.K. Molecular architecture of human prion protein amyloid: A parallel, in-register beta-structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 18946–18951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groveman, B.R.; Dolan, M.A.; Taubner, L.M.; Kraus, A.; Wickner, R.B.; Caughey, B. Parallel in-register intermolecular beta-sheet architectures for prion-seeded prion protein (prp) amyloids. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 24129–24142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnovas, V.; Baron, G.S.; Offerdahl, D.K.; Raymond, G.J.; Caughey, B.; Surewicz, W.K. Structural organization of brain-derived mammalian prions examined by hydrogen-deuterium exchange. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011, 18, 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govaerts, C.; Wille, H.; Prusiner, S.B.; Cohen, F.E. Evidence for assembly of prions with left-handed beta-helices into trimers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 8342–8347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tycko, R.; Savtchenko, R.; Ostapchenko, V.G.; Makarava, N.; Baskakov, I.V. The alpha-helical c-terminal domain of full-length recombinant prp converts to an in-register parallel beta-sheet structure in prp fibrils: Evidence from solid state nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 9488–9497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudjou, M.; Chapuis, J.; Mekrouti, M.; Reine, F.; Herzog, L.; Sibille, P.; Laude, H.; Vilette, D.; Andreoletti, O.; Rezaei, H.; et al. Glycoform-independent prion conversion by highly efficient, cell-based, protein misfolding cyclic amplification. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudjou, M.; Sibille, P.; Fichet, G.; Reine, F.; Chapuis, J.; Herzog, L.; Jaumain, E.; Laferriere, F.; Richard, C.A.; Laude, H.; et al. Highly infectious prions generated by a single round of microplate-based protein misfolding cyclic amplification. MBio 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safar, J.G.; Kellings, K.; Serban, A.; Groth, D.; Cleaver, J.E.; Prusiner, S.B.; Riesner, D. Search for a prion-specific nucleic acid. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 10796–10806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langevin, C.; Andreoletti, O.; Le Dur, A.; Laude, H.; Beringue, V. Marked influence of the route of infection on prion strain apparent phenotype in a scrapie transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011, 41, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaoke, R.; Sakaguchi, S.; Atarashi, R.; Nishida, N.; Arima, K.; Shigematsu, K.; Katamine, S. Early appearance but lagged accumulation of detergent-insoluble prion protein in the brains of mice inoculated with a mouse-adapted creutzfeldt-jakob disease agent. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2000, 20, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, B.; Ness, F.; Tuite, M. Analysis of the generation and segregation of propagons: Entities that propagate the [psi+] prion in yeast. Genetics 2003, 165, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shorter, J.; Lindquist, S. Hsp104 catalyzes formation and elimination of self-replicating sup35 prion conformers. Science 2004, 304, 1793–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.R.; Douglass, A.; Vale, R.D.; Weissman, J.S. Mechanism of prion propagation: Amyloid growth occurs by monomer addition. PLoS Biol. 2004, 2, e321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, M.; Legname, G.; Altafini, C. Investigating the conformational stability of prion strains through a kinetic replication model. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Orgel, L.E. Prion replication and secondary nucleation. Chem. Biol. 1996, 3, 413–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, E.; Peretz, D.; Ball, H.; Sakurai, H.; Legname, G.; Serban, A.; Prusiner, S.B.; Burton, D.R.; Williamson, R.A. Immobilized prion protein undergoes spontaneous rearrangement to a conformation having features in common with the infectious form. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legname, G.; Nguyen, H.O.; Peretz, D.; Cohen, F.E.; DeArmond, S.J.; Prusiner, S.B. Continuum of prion protein structures enciphers a multitude of prion isolate-specified phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 19105–19110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Collins, S.R.; Toyama, B.H.; Weissman, J.S. The physical basis of how prion conformations determine strain phenotypes. Nature 2006, 442, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J.I.; Schutt, C.R.; Shikiya, R.A.; Aguzzi, A.; Kincaid, A.E.; Bartz, J.C. The strain-encoded relationship between prp replication, stability and processing in neurons is predictive of the incubation period of disease. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1001317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Montalban, N.; Makarava, N.; Savtchenko, R.; Baskakov, I.V. Relationship between conformational stability and amplification efficiency of prions. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 7933–7940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Calvo, P.; Bett, C.; Sevillano, A.M.; Kurt, T.D.; Lawrence, J.; Soldau, K.; Hammarstrom, P.; Nilsson, K.P.R.; Sigurdson, C.J. Generation of novel neuroinvasive prions following intravenous challenge. Brain Pathol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesebro, B.; Striebel, J.; Rangel, A.; Phillips, K.; Hughson, A.; Caughey, B.; Race, B. Early generation of new prpsc on blood vessels after brain microinjection of scrapie in mice. MBio 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorter, J.; Lindquist, S. Destruction or potentiation of different prions catalyzed by similar hsp104 remodeling activities. Mol. Cell 2006, 23, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beringue, V.; Herzog, L.; Jaumain, E.; Reine, F.; Sibille, P.; Le Dur, A.; Vilotte, J.L.; Laude, H. Facilitated cross-species transmission of prions in extraneural tissue. Science 2012, 335, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Dur, A.; Lai, T.L.; Stinnakre, M.G.; Laisne, A.; Chenais, N.; Rakotobe, S.; Passet, B.; Reine, F.; Soulier, S.; Herzog, L.; et al. Divergent prion strain evolution driven by prpc expression level in transgenic mice. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Iwasaki, Y.; Takao, M.; Saito, Y.; Iwaki, T.; Qi, Z.; Torimoto, R.; Shimazaki, T.; Munesue, Y.; Isoda, N.; et al. A novel combination of prion strain co-occurrence in patients with sporadic creutzfeldt-jakob disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, D.; Beringue, V.; Espinosa, J.C.; Andreoletti, O.; Jaumain, E.; Reine, F.; Herzog, L.; Gutierrez-Adan, A.; Pintado, B.; Laude, H.; et al. Sheep and goat bse propagate more efficiently than cattle bse in human prp transgenic mice. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1001319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, J.C.; Andreoletti, O.; Castilla, J.; Herva, M.E.; Morales, M.; Alamillo, E.; San-Segundo, F.D.; Lacroux, C.; Lugan, S.; Salguero, F.J.; et al. Sheep-passaged bovine spongiform encephalopathy agent exhibits altered pathobiological properties in bovine-prp transgenic mice. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plinston, C.; Hart, P.; Chong, A.; Hunter, N.; Foster, J.; Piccardo, P.; Manson, J.C.; Barron, R.M. Increased susceptibility of human-prp transgenic mice to bovine spongiform encephalopathy infection following passage in sheep. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nee, S. The evolutionary ecology of molecular replicators. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2016, 3, 160235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarava, N.; Baskakov, I.V. The evolution of transmissible prions: The role of deformed templating. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronier, S.; Beringue, V.; Bellon, A.; Peyrin, J.M.; Laude, H. Prion strain- and species-dependent effects of antiprion molecules in primary neuronal cultures. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 13794–13800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronier, S.; Laude, H.; Peyrin, J.M. Prions can infect primary cultured neurons and astrocytes and promote neuronal cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 12271–12276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeber, A.J.; Race, R.E.; Brandner, S.; Priola, S.A.; Sailer, A.; Bessen, R.A.; Mucke, L.; Manson, J.; Aguzzi, A.; Oldstone, M.B.; et al. Astrocyte-specific expression of hamster prion protein (prp) renders prp knockout mice susceptible to hamster scrapie. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 6057–6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Race, R.E.; Priola, S.A.; Bessen, R.A.; Ernst, D.; Dockter, J.; Rall, G.F.; Mucke, L.; Chesebro, B.; Oldstone, M.B. Neuron-specific expression of a hamster prion protein minigene in transgenic mice induces susceptibility to hamster scrapie agent. Neuron 1995, 15, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, C.E.; Kim, C.; Haldiman, T.; van der Merwe, J.; Lau, A.; Yang, J.; Grams, J.; Di Bari, M.A.; Nonno, R.; Telling, G.C.; et al. Prion disease tempo determined by host-dependent substrate reduction. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beringue, V.; Mallinson, G.; Kaisar, M.; Tayebi, M.; Sattar, Z.; Jackson, G.; Anstee, D.; Collinge, J.; Hawke, S. Regional heterogeneity of cellular prion protein isoforms in the mouse brain. Brain 2003, 126, 2065–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foliaki, S.T.; Lewis, V.; Islam, A.M.T.; Ellett, L.J.; Senesi, M.; Finkelstein, D.I.; Roberts, B.; Lawson, V.A.; Adlard, P.A.; Collins, S.J. Early existence and biochemical evolution characterise acutely synaptotoxic prpsc. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Igel-Egalon, A.; Bohl, J.; Moudjou, M.; Herzog, L.; Reine, F.; Rezaei, H.; Béringue, V. Heterogeneity and Architecture of Pathological Prion Protein Assemblies: Time to Revisit the Molecular Basis of the Prion Replication Process? Viruses 2019, 11, 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11050429

Igel-Egalon A, Bohl J, Moudjou M, Herzog L, Reine F, Rezaei H, Béringue V. Heterogeneity and Architecture of Pathological Prion Protein Assemblies: Time to Revisit the Molecular Basis of the Prion Replication Process? Viruses. 2019; 11(5):429. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11050429

Chicago/Turabian StyleIgel-Egalon, Angélique, Jan Bohl, Mohammed Moudjou, Laetitia Herzog, Fabienne Reine, Human Rezaei, and Vincent Béringue. 2019. "Heterogeneity and Architecture of Pathological Prion Protein Assemblies: Time to Revisit the Molecular Basis of the Prion Replication Process?" Viruses 11, no. 5: 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11050429

APA StyleIgel-Egalon, A., Bohl, J., Moudjou, M., Herzog, L., Reine, F., Rezaei, H., & Béringue, V. (2019). Heterogeneity and Architecture of Pathological Prion Protein Assemblies: Time to Revisit the Molecular Basis of the Prion Replication Process? Viruses, 11(5), 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11050429