Changes in Plant Diversity and Community Structure of Different Degraded Habitats Under Restoration in the Niba Mountain Corridor of Giant Panda National Park

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Plot Setting and Monitoring Indicators

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Plant Diversity

2.3.2. Animal Species Diversity

2.3.3. Plant Community Structure

3. Results

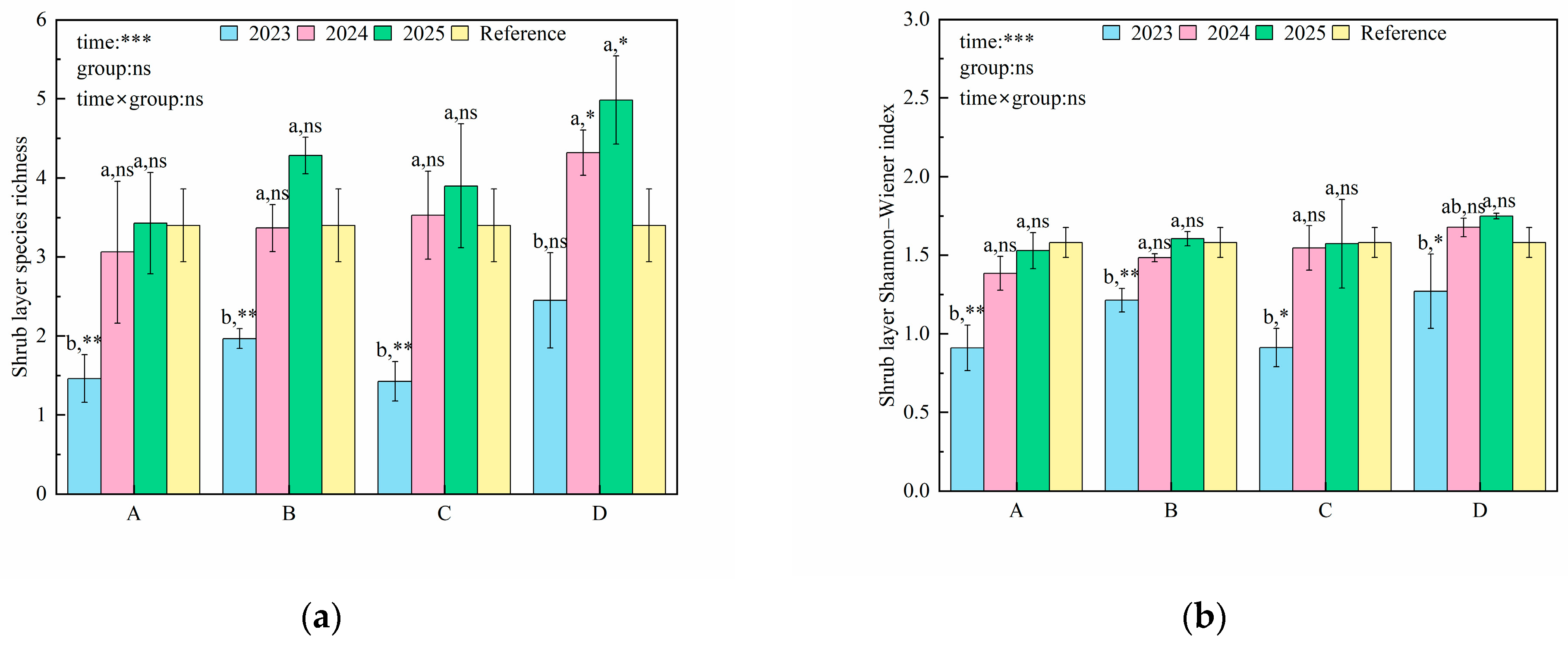

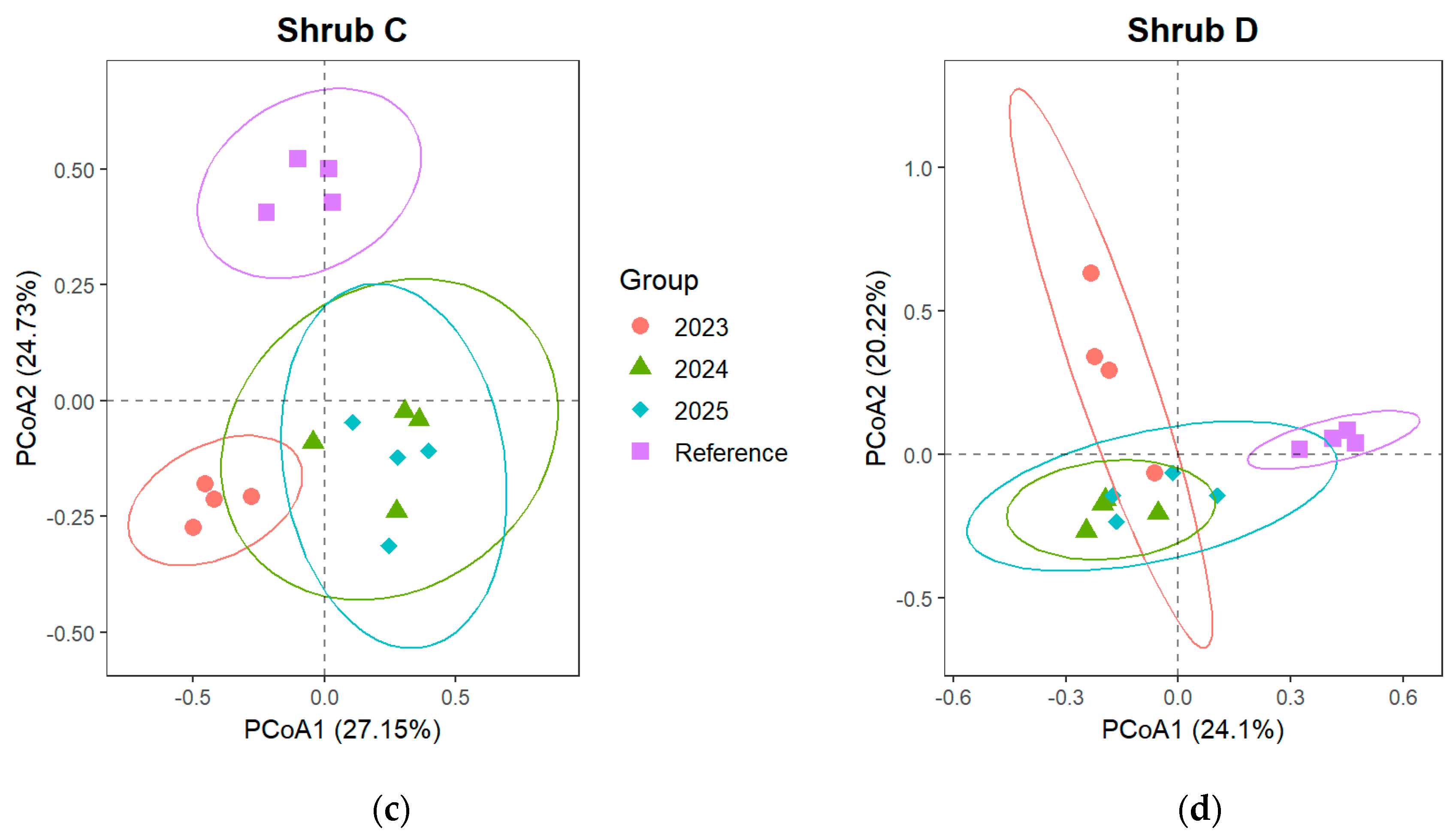

3.1. Changes in Plant Diversity

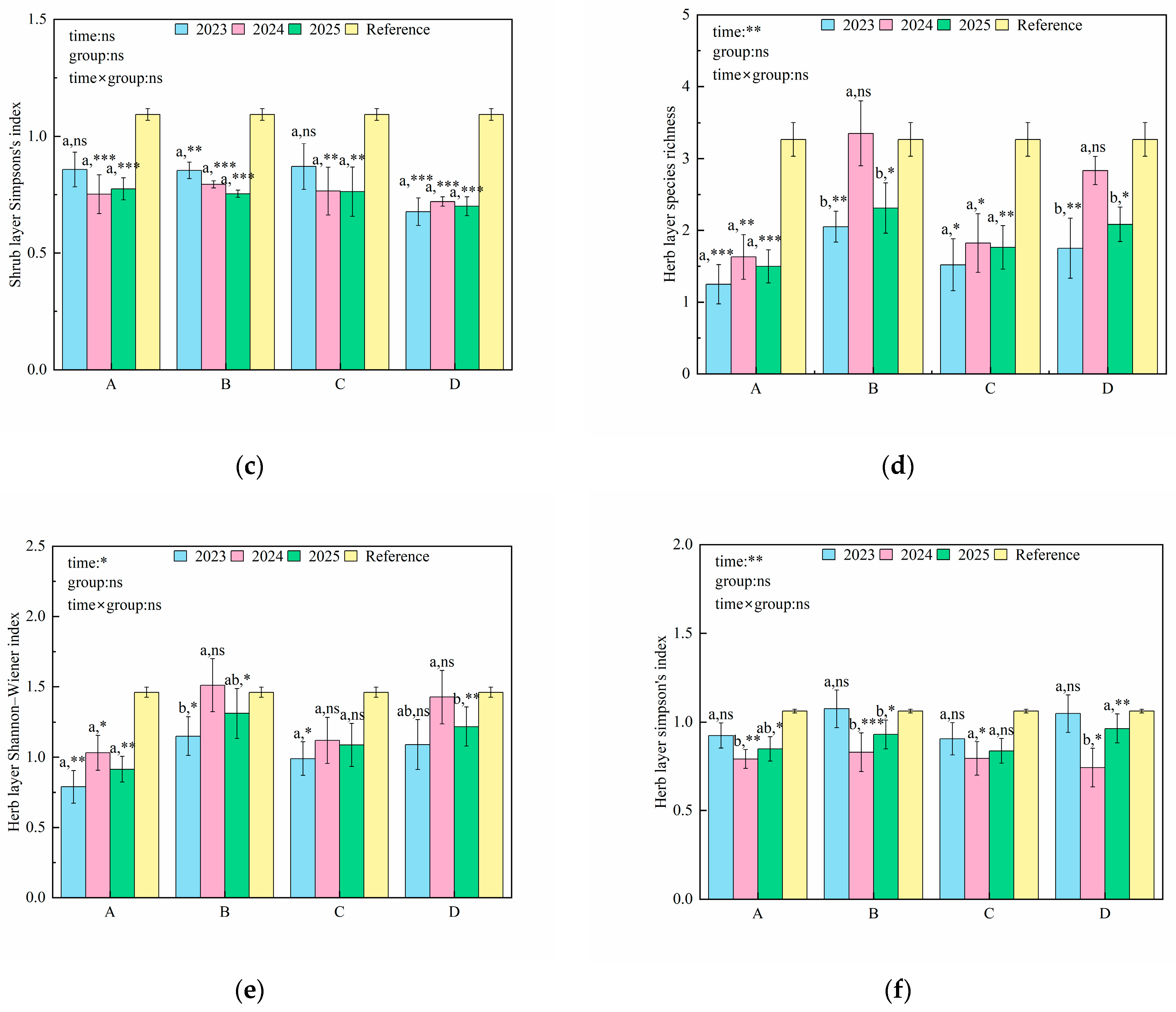

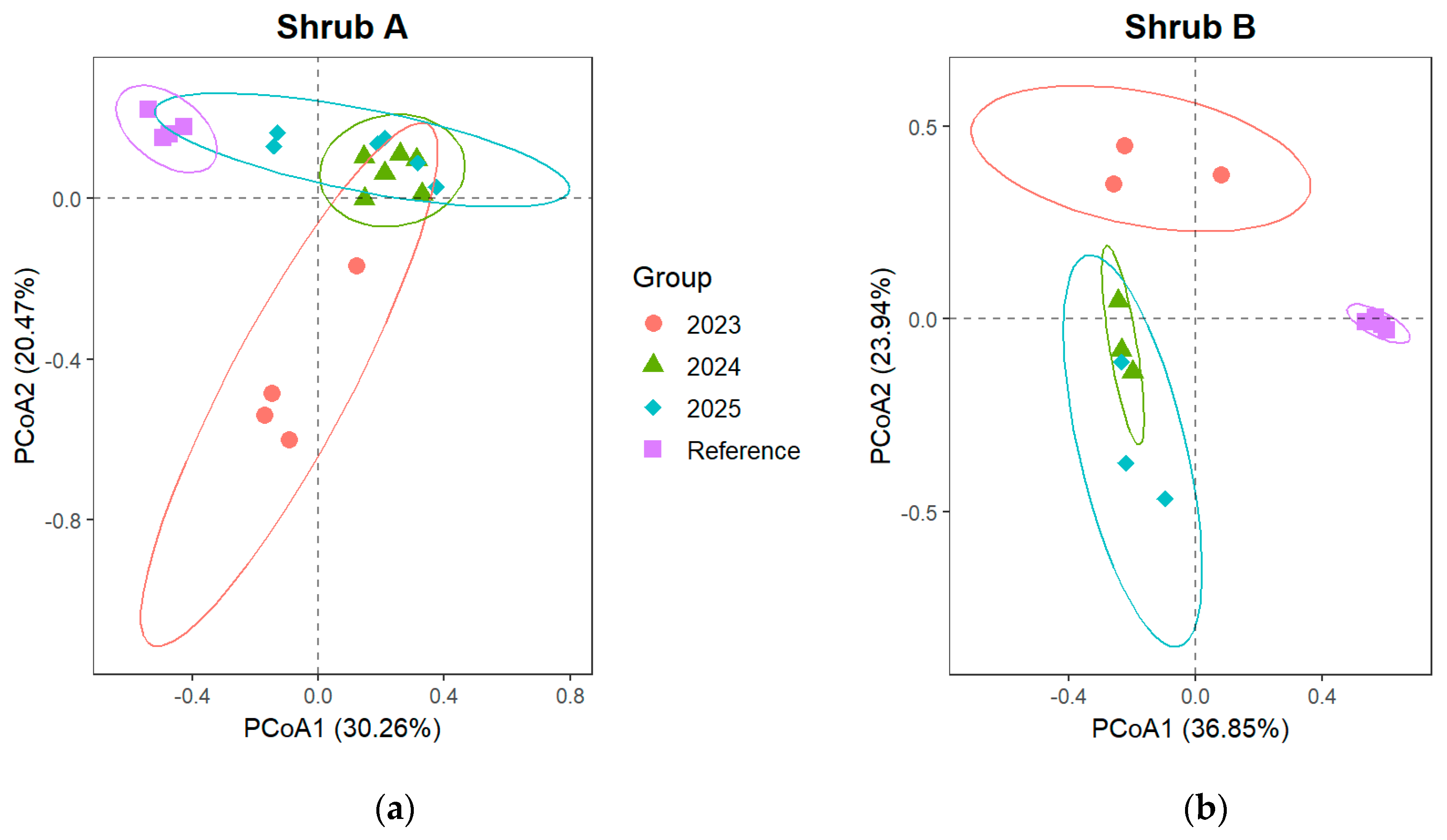

3.2. Changes in Plant Community Structure

3.2.1. Changes in Sorensen Index of Shrub and Herb Layer

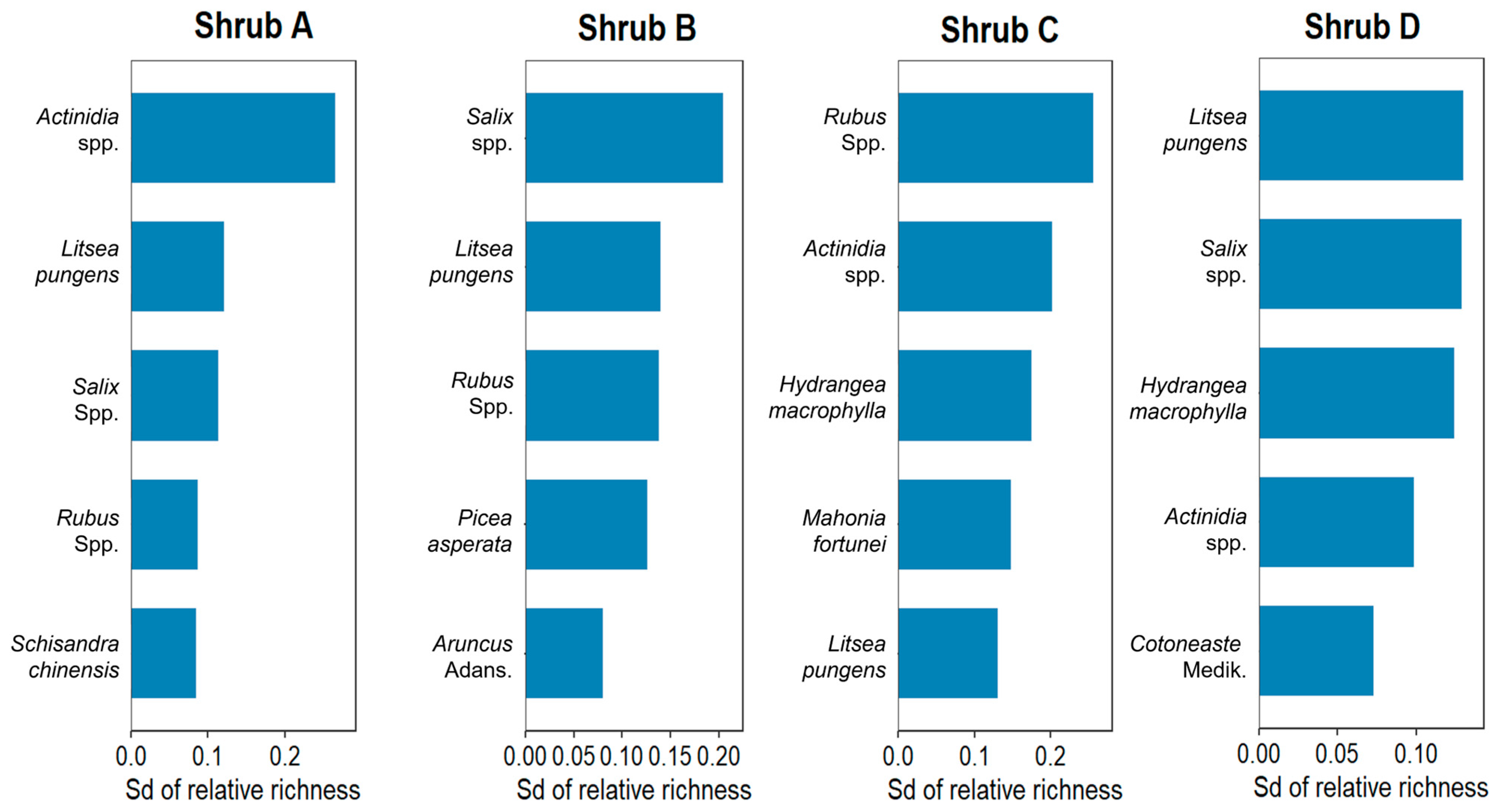

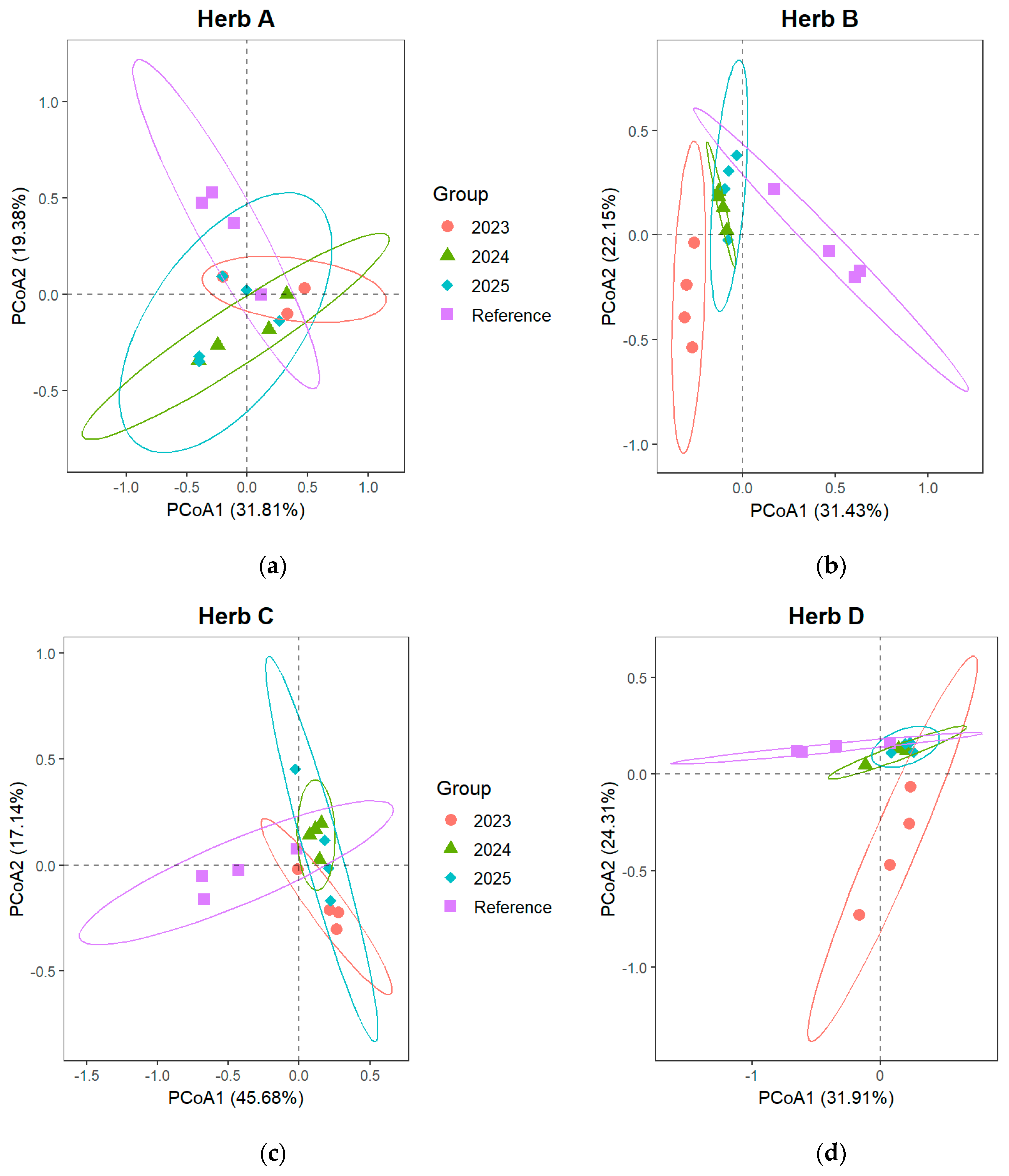

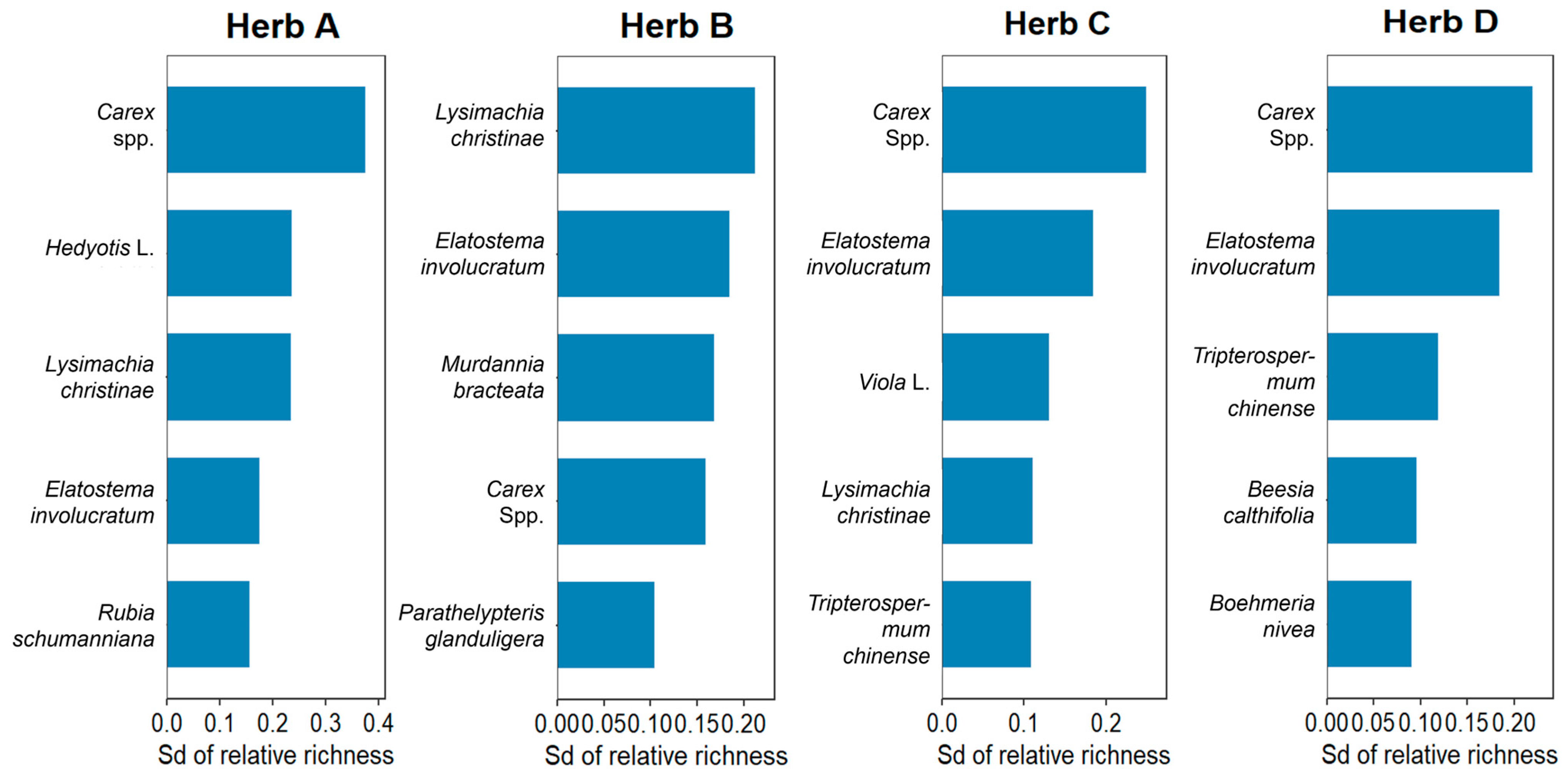

3.2.2. Changes in Community Composition of Shrub and Herb Layer

3.2.3. Changes in Bamboo Regeneration

3.3. Changes in Animal Relative Abundance Index

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Artificial Restoration on Species Diversity

4.2. Effects of Artificial Restoration on Plant Community Structure

4.3. Effect and Suggestions of Artificial Restoration on Degraded Habitat of Giant Panda

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Species | IUCN Red List | If endemic Species | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plants | Decaisnea insignis (Griff.) Hook. f. & Thomson | Endemic species | |

| Enkianthus quinqueflorus Lour. | Least concern | ||

| Rubia schumanniana E. Pritz. | Endemic species | ||

| Rubus setchuenensis Bureau & Franch. | Endemic species | ||

| Tripterospermum chinense (Migo) Harry Sm. | Endemic species | ||

| Animals | Asiatic black bear (Ursus thibetanus G. Cuvier, 1823) | Vulnerable | |

| Masked palm civet (Paguma larvata (C. E. H. Smith, 1827)) | Least concern | ||

| Tufted deer (Elaphodus cephalophus Milne-Edwards, 1872) | Vulnerable | ||

References

- Yuan, R.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Q. The impact of habitat loss and fragmentation on biodiversity in global protected areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 931, 173004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Yu, L.; Newbold, T.; Chen, X. Trends in habitat quality and habitat degradation in terrestrial protected areas. Conserv. Biol. 2025, 39, e14348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, J.M.; Blowes, S.A.; Knight, T.M.; Gerstner, K.; May, F. Ecosystem decay exacerbates biodiversity loss with habitat loss. Nature 2020, 584, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantham, H.S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T.D.; Jones, K.R.; Beyer, H.L.; Schuster, R.; Walston, J.; Ray, J.C.; Robinson, J.G.; Callow, M.; et al. Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Qin, W.; Fu, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Pan, H.; Chen, Z.; Dai, Q.; Yang, Z.; Gu, X.; et al. A conceptual framework for conserving giant panda habitat: Restoration and connectivity. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2025, 100, 2299–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messier, C.; Jürgen, B.; Sousa-Silva, R.; Auge, H.; Baeten, L.; Barsoum, N.; Bruelheide, H.; Caldwell, B.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Dhiedt, E. For the sake of resilience and multifunctionality, let’s diversify planted forests! Conserv. Lett. 2021, 15, e12829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.V.; Pimm, S.L. China’s endemic vertebrates sheltering under the protective umbrella of the giant panda. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Fourth National Giant Panda Survey Report. The Fourth National Giant Panda Survey Report; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2021; p. 269. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Swaisgood, R.R.; Zhang, S.; Nordstrom, L.A.; Wang, H.; Gu, X.; Hu, J.; Wei, F. Old-growth forest is what giant pandas really need. Biol. Lett. 2011, 7, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, N.; Dai, Q.; Ran, J.; Jiao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, C. A corridor design for the giant panda in the Niba Mountain of China. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2014, 20, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G. Habitat Restoration for Ailuropioda melanoleuce. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, R.; Lv, Y.; Lv, B.; Huang, X.; Liu, Q.; Li, D.; Ma, L. Factors influencing species diversity and comparison of indices of understory vegetation in secondary forests at various development stages in the mountains of northern Hebei, China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 11155–11170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Chen, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Chisholm, R.A.; He, F. Pioneer tree species accumulate higher neighbourhood diversity than late-successional species in a subtropical forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 531, 120740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, C.A. The value of animal behavior in evaluations of restoration success. Restor. Ecol. 2008, 16, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Chen, L.; Dong, Z.; Sun, D.; Li, B.; Wangle, X.; Chen, L. Community structure of macrobenthos and ecological health evaluation in the restoration area of the Yellow River Delta wetland. Biodiversity Sci. 2024, 32, 23303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, S.; Dong, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, W. An indicator system for effectiveness evaluation of ecological corridor restorationbased on landscape patterns and ecosystem services. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2023, 31, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Jiang, M.; Xie, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, P.; Qi, C.; Luo, C.; Li, J.; et al. The research on restoration priority assessment of damaged giant panda habitats based on multi-criteria decision analysis of AHP-OWA. Acta Theriol. Sin. 2024, 44, 395–410. Available online: https://www.mammal.cn/EN/10.16829/j.slxb.150878 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Qin, W.; Liu, J.; Song, X.; Pan, H.; Cheng, Y.; Fu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Yang, B. Study on the relationship between tree layer and understory Qiongzhuea multigemmia of forest community in giant panda habitat. Sichuan For. Sci. Technol. 2023, 44, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, J.F.; Kembel, S.W.; Lamb, E.G.; Keddy, P.A. Does phylogenetic relatedness influence the strength of competition among vascular plants? Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 10, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.H.; Strauss, S.Y. More closely related species are more ecologically similar in an experimental test. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaston, K.J.; Williams, P.H. Mapping the world’s species-the higher taxon approach. Biodivers. Lett. 1993, 1, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.-H.; Qiang, S.; Ma, B.; Wei, J.; Chen, J.; Wu, J.; Xie, T.; Shen, X. Influence of long-term rice-duck farming systems on the composition and diversity of weed. J. Plant Ecol. 2006, 30, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, S.J.; Cahill, J.F., Jr.; He, F.; Sólymos, P.; Boutin, S. Regional boreal biodiversity peaks at intermediate human disturbance. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tan, Z.; Wang, Y. Effects of moderate disturbance on species diversity of grassland under different illumination conditions. Sichuan For. Sci. Technol. 2019, 40, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.; Carpenter, S.; Foley, J.A.; Folke, C.; Walker, B. Catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Nature 2001, 413, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suding, K.N.; Gross, K.L.; Houseman, G.R. Alternative states and positive feedbacks in restoration ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holl, K.D.; Aide, T.M. When and where to actively restore ecosystems? For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 261, 1558–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.D.; D’Antonio, C.M. Gone but not forgotten? Invasive plants’ legacies on community and ecosystem properties. Invasive Plant Sci. Manage 2012, 5, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Z.; Tan, H.; Cao, B. Effects of thinning on species diversity and composition of understory herbs in a larch plantation. Chin. J. Ecol. 2006, 25, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Price, J.N.; Morgan, J.W. Woody plant encroachment reduces species richness of herb-rich woodlands in southern Australia. Austral. Ecol. 2008, 33, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, C.; Hao, M.; Choe, C.; He, H. Thinning can increase shrub diversity and decrease herb diversity by regulating light and soil environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 948648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pan, C.; Bao, T.; Ren, J.; Zhao, W. Effects of restoration of artificial sand-fixing vegetation on the diversity of reptiles and mammals in the middle reaches of the Heihe River Basin. J. Desert Res. 2024, 44, 167–177. Available online: http://www.desert.ac.cn/CN/lexeme/showArticleByLexeme.do?articleID=6432 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Derhé, M.A.; Murphy, H.T.; Preece, N.D.; Lawes, M.J.; Menéndez, R. Recovery of mammal diversity in tropical forests: A functional approach to measuring restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2018, 26, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Wei, W.; Zhou, H.; Hong, M.; Fu, M.; Song, X.; YU, J. Study on the activity rhythms of ungulates in Daxiangling Nature Reserve based on infrared camera trapping. Sichuan For. Sci. Technol. 2021, 42, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvreur, M.; Christiaen, B.; Verheyen, K.; Hermy, M. Large herbivores as mobile links between isolated nature reserves through adhesive seed dispersal. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2004, 7, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Cappelli, S.L.; Borer, E.T.; Tilman, D.; Seabloom, E.W. Consumers modulate effects of plant diversity on community stability. Ecol. Lett. 2025, 28, e70103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.W.; Spyreas, G. Convergence and divergence in plant community trajectories as a framework for monitoring wetland restoration progress. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 47, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Sun, T. Effects of vegetation restoration on the species composition and diversity of plantcommunities in the limestone mountains in northern Anhui Province. Pratac. Sci. 2020, 37, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, J.C. Nonperiodic grassland restoration management can promote native woody shrub encroachment. Restor. Ecol. 2022, 30, e13650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tölgyesi, C.; Török, P.; Kun, R.; Csathó, A.I.; Bátori, Z.; Erdős, L.; Vadász, C. Recovery of species richness lags behind functional recovery in restored grasslands. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charton, K.T.; Damschen, E.I. Grassland woody plant management rapidly changes woody vegetation persistence and abiotic habitat conditions but not herbaceous community composition. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 61, 2020–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricsfalusy, V.V.; Godfrey, A.; Chakma, K.; Stewart, A.; Danylyk, I.M. Evaluating the diversity, distribution patterns and habitat preferences of Carex species (Cyperaceae) in western Canada using geospatial analysis. Biodivers. Data J. 2025, 13, e144840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; He, D.; Shang, T.; Hu, L.; Xiong, K. A preliminary research on the after-earthquake succession of the vegetation in Longxi-Hongkou national nature reserve. Sichuan For. Sci. Technol. 2015, 36, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, C.H.; Woodbridge, M. Successional trajectories differ among post-harvest and mature cove and upland hardwood forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 596, 123091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toledo, R.M.; Pivello, V.R.; Vangansbeke, P.; Jakovac, C.; Verheyen, K.; Verdade, L.M.; de Lima, R.A.F. Reassembly dynamics of tropical secondary succession: Evidence from atlantic forests. J. Ecol. 2025, 113, 2106–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, D.C. Applying trait-based models to achieve functional targets for theory-driven ecological restoration. Ecol. Lett. 2014, 17, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denslow, J.S. Gap partitioning among tropical rainforest trees. Biotropica 1980, 12, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; He, X.; Liu, X. Analysis on quality situation after intermediate felling of Bashania fargesii, pandas’ staple bamboo in Fuping Nature Reserve in Shangxi. For. Inventory Plan. 2008, 33, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Zheng, X.; Liu, X.; Cai, X. Study on regeneration and effect of Bashania bamboo forest after strip thinning in Foping Nature Reserve, China. For. Grassl. Resour. Res. 2011, 3, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Degradation Type | Characteristics | Restoration Measures | Group | Quadrats Number | Prevailing Plant Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure plantation (with bamboo) | High canopy density Sparse bamboo | Increase light transmission Tending bamboo | A | 7 | Abies fabri, Picea asperata, Cryptomeria japonica var. sinensis Miquel |

| Pure plantation (without bamboo) | High canopy density Bamboo absence | Increase light transmission Replanting bamboo | B | 3 | Abies fabri, Picea asperata, Cryptomeria japonica var. sinensis |

| Secondary forests (with high density bamboo) | High bamboo density Arbor absence | Strip thinning Tending arbor | C | 4 | Qiongzhuea multigemmia, Actinidia spp. |

| Secondary forests (without bamboo) | Low bamboo coverage Canopy fragmentation | Cleaning lush shrubs Tending arbor | D | 3 | Actinidia spp. |

| Suitable habitats | Moderate canopy density Moderate bamboo | - | Reference | 3 | Mixed forests of coniferous and broad-leaved trees such as Abies fabri, Picea asperata, Acer, Rhododendron L. |

| Group | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.19 | 0.46 | 0.65 |

| B | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.46 |

| C | 0.21 | 0.61 | 0.65 |

| D | 0.42 | 0.63 | 0.67 |

| Group | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.34 |

| B | 0.09 | 0.30 | 0.37 |

| C | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.30 |

| D | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.40 |

| Number of Dead Bamboo | Number of Live Shoots | Number of Dead Shoots | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2024 | 2025 | |

| A | 1.02 (0.25) b | 0.61 (0.26) b | 2.28 (0.39) a | 1.16 (0.20) Ab | 1.76 (0.24) Ca | 0.64 (0.06) Bc | 0.79 (0.17) a | 0.61 (0.00) a |

| B | 0.61 (0.36) a | 0.61 (0.37) a | 0.98 (0.55) a | 1.23 (0.29) Ab | 4.91 (0.35) Aa | 0.97 (0.08) Ab | 1.31 (0.25) a | 0.61 (0.00) b |

| C | 0.61 (0.31) a | 1.28 (0.32) a | 1.27 (0.47) a | 1.39 (0.25) Ab | 3.23 (0.30) Ba | 0.61 (0.07) Bc | 0.78 (0.21) a | 0.61 (0.00) a |

| D | 0.61 (0.31) a | 0.61 (0.32) a | 1.05 (0.47) a | 0.83 (0.25) Ab | 3.37 (0.30) Ba | 0.61 (0.07) Bb | 0.88 (0.21) a | 0.61 (0.00) a |

| p | time: * | time: *** | time: ** | |||||

| group: ns | group: ** | group: ns | ||||||

| time * × group: ns | time × group: *** | time × group: ns | ||||||

| Month | May | Jun. | Jul. | Aug. | Sept. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infrared camera working day | 88 | 48 | 92 | 52 | 29 | 55 | 9 | 52 | 425 |

| Total number of valid photos | 3 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 32 |

| Month | Masked Palm Civet | Asiatic Black Bear | Tufted Deer | Wild Boar | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Valid Photos | RAI | Number of Valid Photos | RAI | Number of Valid Photos | RAI | Number of Valid Photos | RAI | |

| May | 1 | 1.14 | 1 | 1.14 | 1 | 1.14 | ||

| Jun. | 2 | 4.17 | 6 | 12.50 | ||||

| Jul. | 6 | 6.52 | ||||||

| Aug. | 6 | 11.54 | ||||||

| Sept. | 1 | 3.45 | 1 | 3.45 | ||||

| Oct. | 2 | 3.64 | ||||||

| Nov. | 2 | 22.22 | 1 | 11.11 | ||||

| Dec. | 2 | 3.85 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shen, Q.; Zhang, D.; Tang, M.; Li, P.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Fu, M.; Chen, Z.; Xiong, X.; Song, X.; et al. Changes in Plant Diversity and Community Structure of Different Degraded Habitats Under Restoration in the Niba Mountain Corridor of Giant Panda National Park. Forests 2026, 17, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010038

Shen Q, Zhang D, Tang M, Li P, Liu J, Jiang Y, Fu M, Chen Z, Xiong X, Song X, et al. Changes in Plant Diversity and Community Structure of Different Degraded Habitats Under Restoration in the Niba Mountain Corridor of Giant Panda National Park. Forests. 2026; 17(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Qian, Dongling Zhang, Ming Tang, Ping Li, Jingyi Liu, Yuzhou Jiang, Mingxia Fu, Zhangmin Chen, Xilin Xiong, Xinqiang Song, and et al. 2026. "Changes in Plant Diversity and Community Structure of Different Degraded Habitats Under Restoration in the Niba Mountain Corridor of Giant Panda National Park" Forests 17, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010038

APA StyleShen, Q., Zhang, D., Tang, M., Li, P., Liu, J., Jiang, Y., Fu, M., Chen, Z., Xiong, X., Song, X., & Yang, B. (2026). Changes in Plant Diversity and Community Structure of Different Degraded Habitats Under Restoration in the Niba Mountain Corridor of Giant Panda National Park. Forests, 17(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010038