Effects of PDADMAC Solution Pretreatment on Beech Wood—Waterborne Coating Interaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Wood Samples

2.2. Treatment of Wood Samples with PDADMAC Solutions

2.3. Surface Finishing of Untreated and Treated Wood Samples

2.4. Characterisation of the Wood Surface Pretreatment with PDADMAC Solution

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. FT-IR Analysis

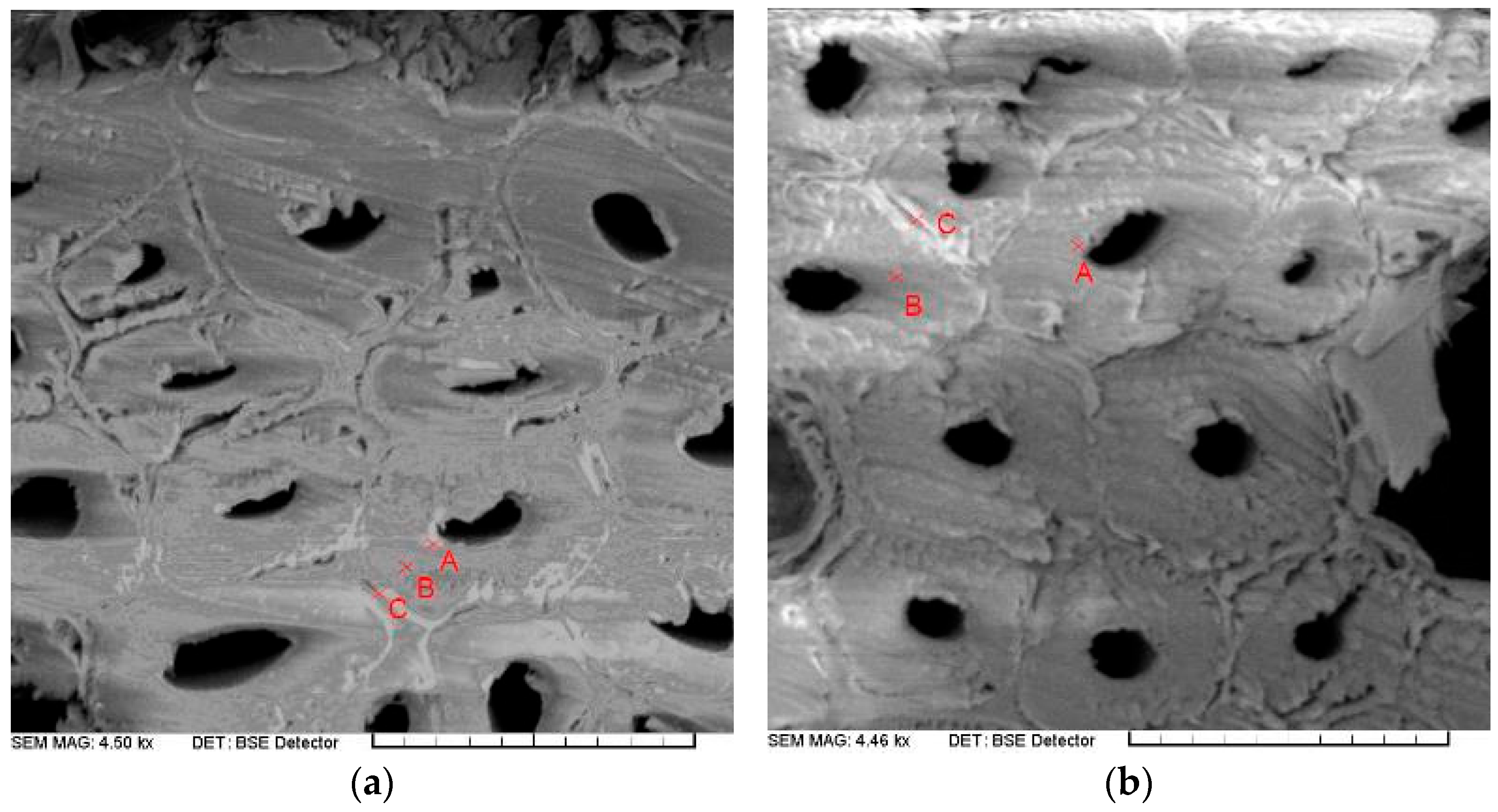

3.2. Penetration Depth of PDADMAC Solution

3.3. Surface Characterisation of the Treated Samples

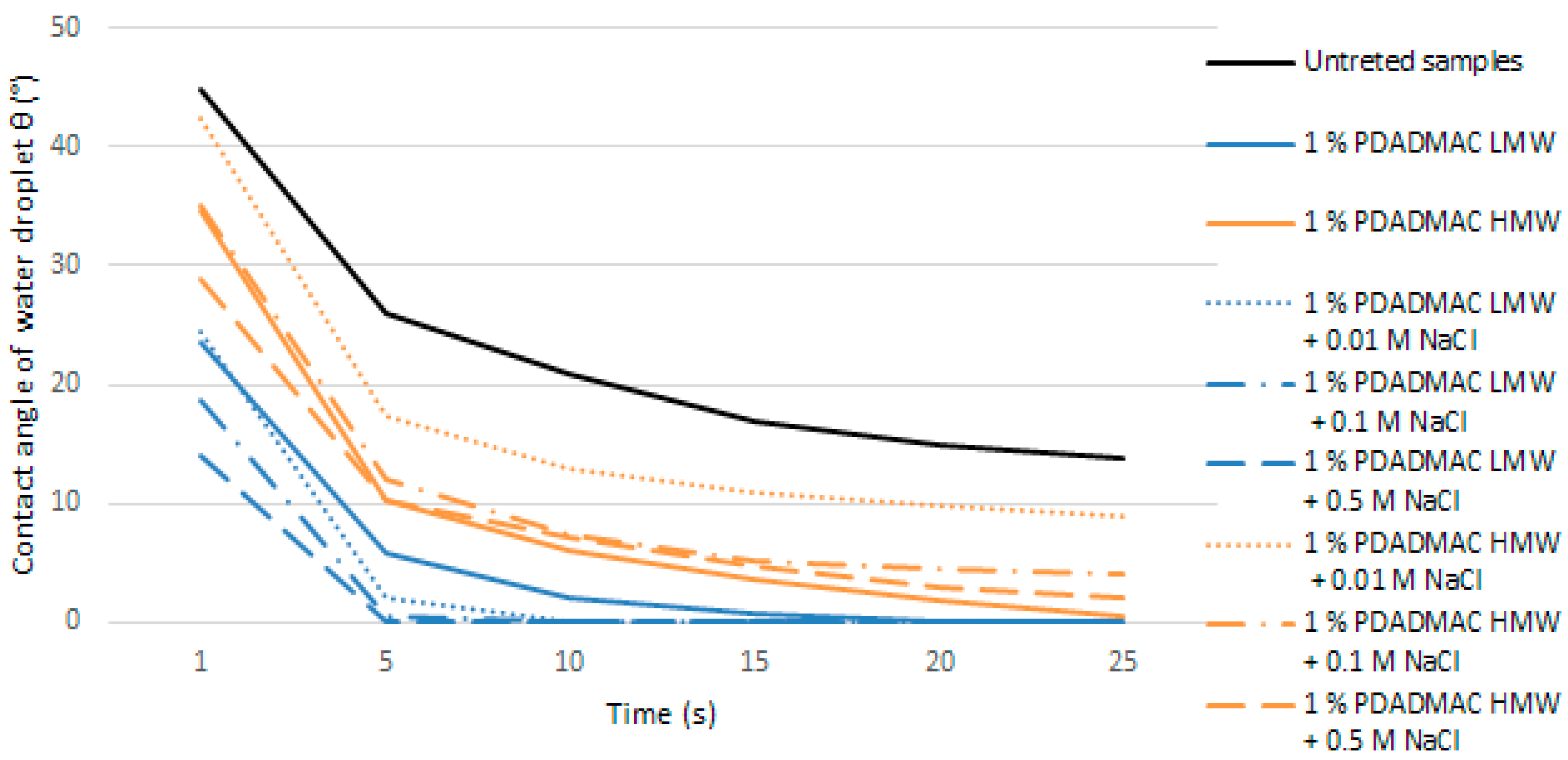

3.4. Wood Surface Energy

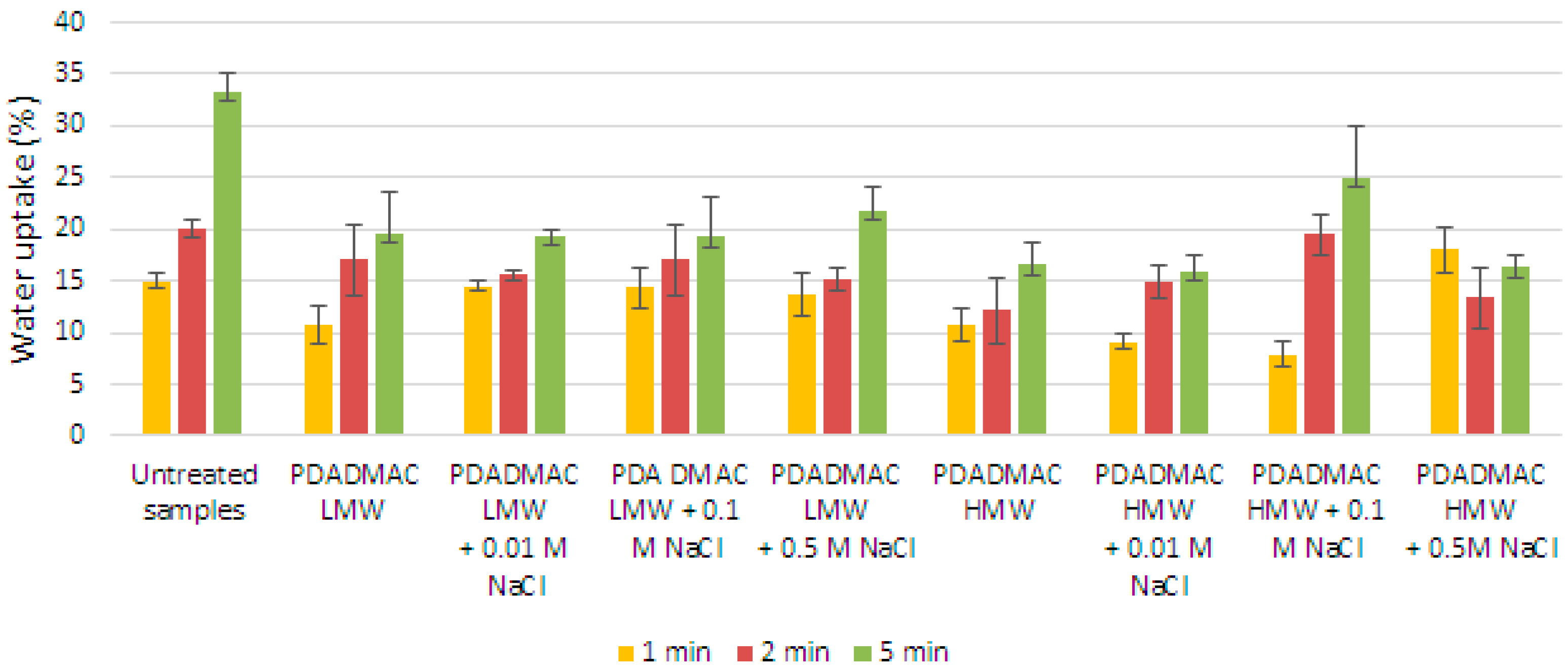

3.5. Water Absorption

3.6. Wood Surface Roughness After PDADMAC Treatment

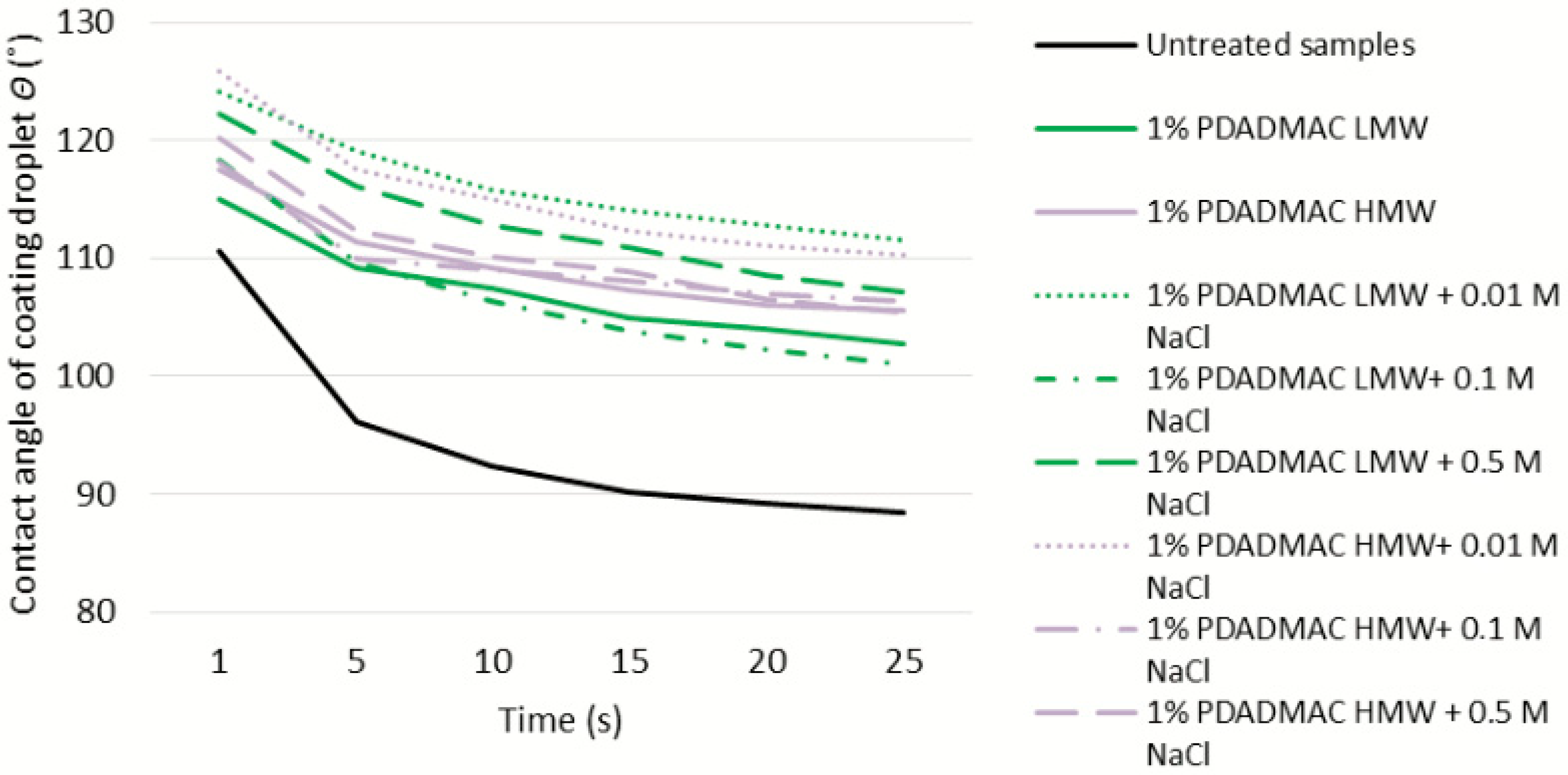

3.7. Dry Film Thickness of WTAC

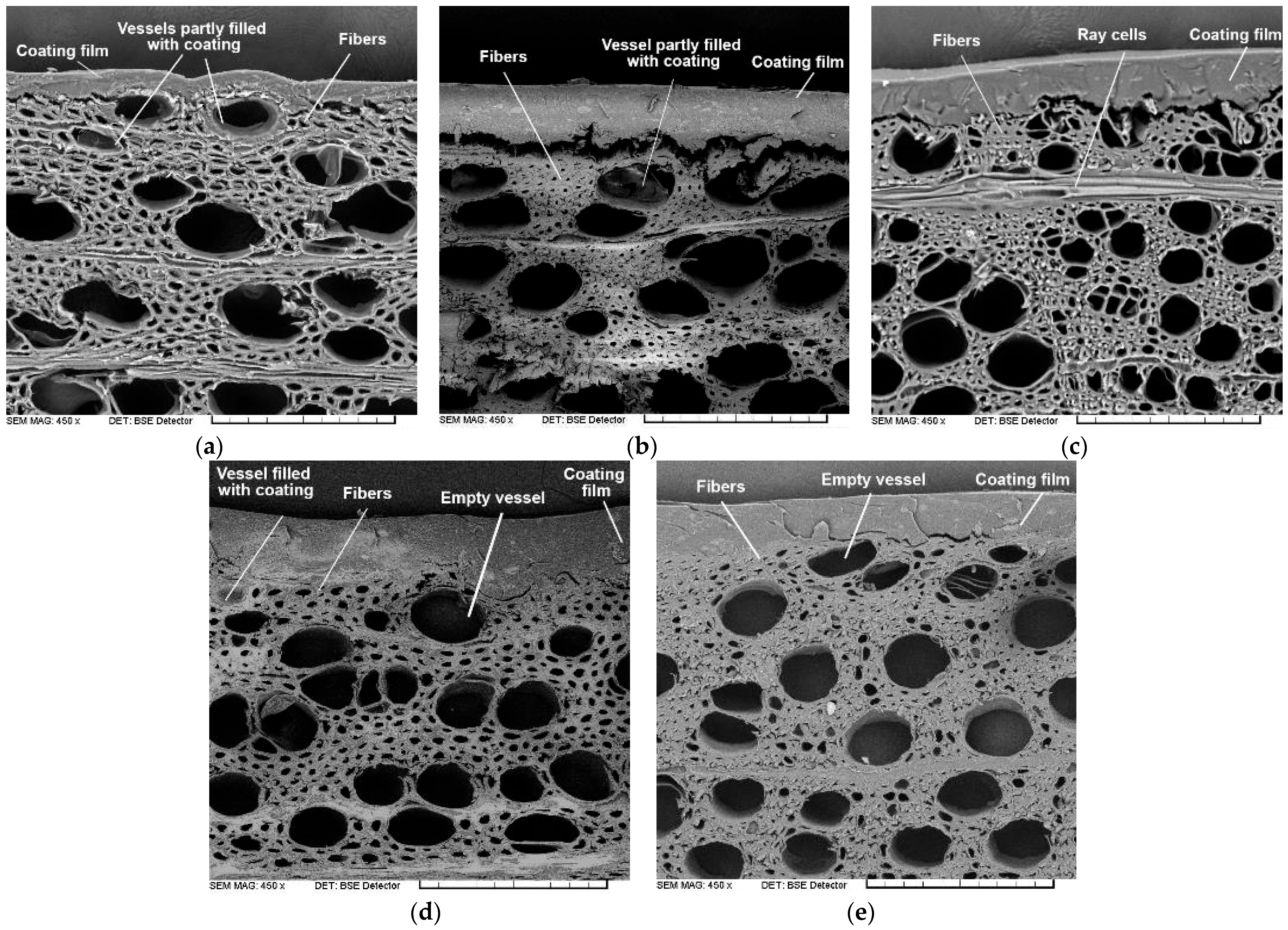

3.8. Penetration Parameters of WTAC

3.9. The Adhesion Strength of WTAC

3.10. The Surface Roughness of the Wood’s Coated Surface

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meyer, F.; Elliot, T.; Craig, S.; Goldstein, B.P. The Carbon Footprint of Future Engineered Wood Construction in Montreal The Carbon Footprint of Future Engineered Wood Construction in Montreal. Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. 2024, 4, 015012. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet, P.; Breton, C. Wood Productions and Renewable Materials: The Future Is Now. Forests 2020, 11, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirouš-Rajković, V.; Miklečić, J. Enhancing Weathering Resistance of Wood—A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, J.; Yan, X.; Li, J. A Review on the Effect of Wood Surface Modification on Paint. Coatings 2024, 14, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, V.; Pierre, B. Surface Preparation of Wood for Application of Waterborne Coatings. For. Prod. J. 2012, 62, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, W. Effect of Coating Process on Properties of Two-Component. Coatings 2022, 12, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topçuoğlu, Ö.; Altinkaya, S.A.; Balköse, D. Characterization of Waterborne Acrylic Based Paint Films and Measurement of Their Water Vapor Permeabilities. Prog. Org. Coat. 2006, 56, 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Copak, A.; Jirouš-Rajković, V.; Živković, V.; Miklečić, J. Water Vapour Transmission Properties of Uncoated and Coated Wood-Based Panels. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 18, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowell, R.M. Understanding Wood Surface Chemistry and Approaches to Modification: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, M.Z.; Aranda, F.L.; Hernandez-Tenorio, F.; Garrido-Miranda, K.A.; Meléndrez, M.F.; Palacio, D.A. Polyelectrolytes for Environmental, Agricultural, and Medical Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, R.; Swaboda, C.; Petzold, G.; Emmler, R.; Simon, F. Controlling the Water Uptake of Wood by Polyelectrolyte Ad-sorption. Prog. Org. Coat. 2011, 72, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, W.; TenWolde, A. Physical Properties and Moisture Relations of Wood. In The Encyclopedia of Wood; Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. Nanoscale Surface Modification of Wood Veneers for Adhesion. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Palija, T. The Impact of Polyelectrolyte on Interaction between Wood and Water-Borne Coatings. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Belgrade Faculty of Foresty, Belgrade, Serbia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Palija, T.; Rančić, M.; Djikanović, D.; Radotić, K.; Petrič, M.; Pavlič, M. Effects of Beech Wood Surface Treatment with Poly-ethylenimine Solution Prior to Finishing with Water-Based Coating. Polymers 2025, 17, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gaudio, F.; Barreca, S.; Orecchio, S. Diallyldimethylammonium Chloride (DADMAC) in Water Treated with Poly-Diallyldimethylammonium Chloride (PDADMAC) by Reversed-Phase Ion-Pair Chromatography—Electrospray Ion-ization Mass Spectrometry. Separations 2023, 10, 311. [Google Scholar]

- Razali, M.A.A.; Ahmad, Z.; Ariffin, A. Treatment of Pulp and Paper Mill Wastewater with Various Molecular Weight of PolyDADMAC Induced Flocculation with Polyacrylamide in the Hybrid System. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2012, 2, 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigareva, V.A.; Senchikhin, I.N.; Bolshakova, A.V.; Sybachin, A.V. Modification of Polydiallyldimethylammonium Chloride with Sodium Polystyrenesulfonate Dramatically Changes the Resistance of Polymer-Based Coatings towards Wash-Off from Both Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Surfaces. Polymers 2022, 14, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Mohseni, M. Development of Poly (Diallyldimethylammonium) Chloride-Modified Activated Carbon for Efficient Adsorption of Methyl Red in Aqueous Systems. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, M.A.A.; Hanafi, I.; Ariffin, A. Graft Copolymerization of PolyDADMAC to Cassava Starch: Evaluation of Process Variables via Central Composite Design. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 65, 535–545. [Google Scholar]

- Wagberg, L. Polyelectrolyte Adsorption on Cellulose Fibres—A Review. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2000, 15, 586–597. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, A.E. The Effects of Cellulosic Fiber Charges on Polyelectrolyte Adsorption and Fiber-Fiber Interactions. Ph.D. Thesis, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Žigon, J.; Petrič, M.; Dahle, S. Dielectric and Surface Properties of Wood Modified with NaCl Aqueous Solutions and Treated with FE-DBD Atmospheric Plasma. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2021, 79, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 13061-1:2014; Physical and Mechanical Properties of Wood—Test Methods for Small Clear Wood Specimens—Part 1: Determination of Moisture Content for Physical and Mechanical Tests. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- EN ISO 3251:2019; Paints, Varnishes and Plastics—Determination of Non-Volatile-Matter Content. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- EN ISO 2811-1:2016; Paints and Varnishes—Determination of Density—Pycnometer Method. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- EN ISO 2431:2012; Paints and Varnishes—Determination of Flow Time by Use of Flow Cups. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- EN ISO 2555:2018; Plastics—Resins in the Liquid State or as Emulsions or Dispersions—Determination of Apparent Viscosity Using a Single Cylinder Type Rotational Viscometer Method. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- ISO 304:1985; Surface Active Agents—Determination of Surface Tension by Drawing up Liquid Films. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1985.

- Derrick, M.R.; Stulik, D.; Landry, J.M. Infrared Spectroscopy in Conservation Science; Scientific Tools for Conservation; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Đikanović Golubović, D. Strukturna Ispitivanja Ćelijskog Zida i Lignina Različitog Porekla. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- EN 828:2013; Adhesives—Wettability—Determination by Measurement of Contact Angle and Surface Free Energy of Solid Surface. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- Chibowski, E.; Perea-Carpio, R. Problems of Contact Angle and Solid Surface Free Energy Determination. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 98, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 4287:1997; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface Texture: Profile Method—Terms, Definitions and Surface Texture Parameters. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997.

- EN ISO 2808:2019; Paints and Varnishes—Determination of Film Thickness. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Van den Bulcke, J.; Rijckaert, V.; Van Acker, J.; Stevens, M. Quantitative Measurement of the Penetration of Water-Borne Coatings in Wood with Confocal Lasermicroscopy and Image Analysis. Holz als Roh-und Werkst. 2003, 61, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bulcke, J.; Boone, M.; Van Acker, J.; Van Hoorebeke, L. High-Resolution X-Ray Imaging and Analysis of Coatings on and in Wood. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2010, 7, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 4624:2023; Paints and Varnishes—Pull-Off Test for Adhesion. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Tolvaj, L. Monitoring of Photodegradation for Wood by Infrared Spectroscopy. In Proceedings of the COST Action IE0601 Conference, Hamburg, Germany, 7–9 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mohebby, B. Attenuated Total Reflection Infrared Spectroscopy of White-Rot Decayed Beech Wood. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2005, 55, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, M.-L.; Kronkright, D.P.; Norton, R.E. The Conservation of Artifacts Made from Plant Materials; Getty Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Stevanović-Janežić, T. Hemija Drveta Sa Hemijskom Preradom; Jugoslaviapublik: Belgrade, Serbia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C.Y.; Marchessault, R.H. Infrared Spectra of Crystalline Polysaccharides I. Hydrogen Bonds in Native Celluloses. J. Polym. Sci. 1959, 37, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faix, O. Classification of Lignin from Different Botanical Origins by FT-IR Spectroscopy. Holzforschung 1991, 45, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.K. A Study of Chemical Structure of Soft and Hardwood and Wood Polymers by FTIR Spectroscopy. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1999, 71, 1969–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, M.; Najafi, A.; Yousefian, S.; Reza Naji, H.; Suhaimi Bakar, E. Water Repellent Effect and Dimension Stability of Beech Wood Impregnated with Nano-Zinc Oxide. BioResources 2013, 8, 6280–6287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solár, R.; Kurjatko, S.; Mamon, M.; Košíková, B.; Neuschlová, E.; Výbohová, E.; Hudec, J. Selected Properties of Beech Wood Degraded by Brown-Rot Fungus Coniophora puteana. Drv. Ind. 2007, 58, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, C.M.; Vasile, C.; Popescu, M.C.; Singurel, G. Degradation of Lime Wood Painting Supports II. Spectral Characterisation. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2006, 40, 649–658. [Google Scholar]

- Lujan Luna, M.; Marace, M.A.; Robledo, G.L.; Saparrat, M.C. Characterization of Schinopsis haenkeana Wood Decayed by Phellinus chaquensis (Basidiomycota, Hymenochaetales). IAWA J. 2012, 33, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolvaj, L.; Faix, O. Artificial Ageing of Wood Monitored by DRIFT Spectroscopy and CIE Lab* Color Measurements. Holzforschung 1995, 49, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, R.; Suzuki, H.; Kamiyama, T.; Sugiyama, J. Variation of Microfibril Angles and Chemical Composition: Implication for functional properties. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 2003, 22, 963–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.K.; Pitman, A. FTIR Studies of the Changes in Wood Chemistry Following Decay by Brown-Rot and White-Rot Fungi. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2003, 52, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C. Wood Modification Chemical, Thermal and Other Processes; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2006; ISBN 9780470021729. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A.M.; Jutton, F.; Remsen, E.E. Characterization of Fl Uorescent Poly (Diallyldimethylammonium Ion)—Sulfonated Rhodamine Dye Complexes and Their Interactions with Chloride and Carboxylate Ions. Polym. Int. 2025, 74, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žigon, J.; Kovač, J.; Petrič, M. The Influence of Mechanical, Physical and Chemical Pre-Treatment Processes of Wood Surface on the Relationships of Wood with a Waterborne Opaque Coating. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 162, 106574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbe, M.A. Bonding between Cellulosic Fubers in the Absence and Presence of Dry-Strenhgt Agents—A Review. BioResources 2006, 1, 281–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjurhager, I. Effects of Cell Wall Structure on Tensile Properties of Hardwood; KTH Chemical Science and Engineering: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jaić, M.; Palija, T. Uticaj Vrste Drveta i Sistema Površinske Obrade Na Adheziju Premaza. Zaštita Mater. 2012, 53, 299–303. [Google Scholar]

| Polyelectrolyte | Manufacturer | Molecular Weight, g/mol | Abbreviation | NaCl Concentration in 1% Solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (PDADMAC) | Katpol-Chemie Bitterfeld, Germany | 8000 | PDADMAC LMW | / 0.01 M 0.1 M 0.5 M |

| Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH Taufkirchen, Germany | 100,000–200,000 | PDADMAC HMW | / 0.01 M 0.1 M 0.5 M |

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Band Assignment | Component/Functional Group |

|---|---|---|

| 3600–3000 | O–H stretching vibrations (hydrogen-bonded OH groups) | Cellulose, hemicellulose, and adsorbed water [31,39,40,43] |

| 2958 | C–H asymmetric stretching in methyl and methylene groups | Lignin and hemicellulose [44,45] |

| 2920 | C–H symmetric stretching in methyl and methylene groups | Lignin, hemicellulose, and extractives [44,45] |

| 1739 | C=O stretching in unconjugated ketone or ester groups | Hemicellulose (acetyl and uronic ester groups) [46] |

| 1640 | C=O stretching vibration in conjugated carbonyl groups | Lignin (conjugated with aromatic rings) [39,47] |

| 1510 | Aromatic skeletal vibrations | Lignin (aromatic ring vibrations of guaiacyl and syringyl units) [44] |

| 1457 | CH2 deformation stretching | Lignin and xylan [48] |

| 1425 | Aromatic skeletal vibrations combined with C–H in-plane deformation | Lignin and cellulose [48] |

| 1371 | Aliphatic C–H bending and O–H deformation in phenolic OH | Cellulose and hemicellulose [49,50] |

| 1320 | C1–O vibrations in syringyl derivatives; CH in-plane bending | Cellulose I and II [48,49] |

| 1267 | Syringyl ring breathing and C–O stretching | Lignin and xylan [48] |

| 1160 | C–O–C asymmetric stretching | Cellulose I and II (β-glycosidic linkages) [48] |

| 1059 | C–O stretching vibration | Cellulose and hemicellulose [48] |

| 1034 | C–O stretching vibration | Cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [49,51,52] |

| 897 | C1–H deformation and glycosidic bond vibration | Cellulose (β-glycosidic linkages) [48,50] |

| Surface Layer | Inner Layer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated Samples | Measurement Point | Element Content, % | Element Content, % | ||||

| C | O | Cl | C | O | Cl | ||

| PDADMAC LMW | Point A | 66.00 | 33.56 | 0.44 | 61.38 | 38.07 | 0.55 |

| Point B | 62.86 | 36.77 | 0.37 | 66.03 | 33.74 | 0.24 | |

| Point C | 64.40 | 34.54 | 1.07 | 66.82 | 32.59 | 0.60 | |

| Average value | 64.42 | 34.96 | 0.63 | 64.74 | 34.80 | 0.46 | |

| Minimal–maximal value | 62.86–66.00 | 33.56–36.77 | 0.37–1.07 | 61.38–66.82 | 32.59–38.07 | 0.24–0.60 | |

| Standard deviation | 1.57 | 1.65 | 0.39 | 2.94 | 2.89 | 0.20 | |

| PDADMAC HMW | Point A | 72.2 | 21.92 | 5.88 | 65.8 | 33.34 | 0.86 |

| Point B | 69.64 | 28.99 | 1.38 | 66.59 | 33.14 | 0.28 | |

| Point C | 72.07 | 26.47 | 1.47 | 75.58 | 24.08 | 0.34 | |

| Average value | 71.30 | 25.79 | 2.91 | 69.32 | 30.18 | 0.49 | |

| Minimal–maximal value | 69.64–72.20 | 21.92–28.99 | 1.38–5.88 | 65.80–75.58 | 24.08–33.34 | 0.28–0.86 | |

| Standard deviation | 1.44 | 3.58 | 2.57 | 5.43 | 5.29 | 0.32 | |

| Group of Samples | NaCl Concentration | Surface Energy, mJ/m2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γLW | γAB | γ | |||

| Untreated samples | / | 48.2 | 10.5 | 58.7 | |

| Treated samples | PDADMAC LMW | / | 45.9 | 11.3 | 57.2 |

| 0.01 M | 47.6 | 9.8 | 57.5 | ||

| 0.1 M | 46.8 | 10.0 | 56.8 | ||

| 0.5 M | 48.3 | 8.4 | 56.7 | ||

| PDADMAC HMW | / | 46.2 | 11.8 | 58.0 | |

| 0.01 M | 43.8 | 14.2 | 58.0 | ||

| 0.1 M | 47.3 | 10.4 | 57.7 | ||

| 0.5 M | 46.3 | 10.8 | 57.0 | ||

| NaCl Concentration | Ra of Treated Wood Surface, µm | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| / | 0.01 M | 0.1 M | 0.5 M | |||||

| 1% PDADMAC LMW | 8.61 | b z | 6.83 | a x y | 7.32 | b y | 6.35 | a x |

| 1% PDADMAC HMW | 7.27 | a y | 6.83 | a x | 6.49 | a x | 7.00 | b x |

| Dry Film Thickness (DFT) of WTAC *, µm | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated Samples | Treated Samples | |||||||

| PDADMAC LMW | PDADMACHMW | |||||||

| NaCl Concentration | NaCl Concentration | |||||||

| 57.80 (5.27) | / | 0.01 M | 0.1 M | 0.5 M | / | 0.01 M | 0.1 M | 0.5 M |

| 54.67 (6.63) | 56.20 (5.51) | 59.17 (6.09) | 56.13 (6.14) | 56.83 (9.85) | 59.03 (6.49) | 61.23 (6.81) | 66.10 (9.36) | |

| Samples | NaCl Concentration | Penetration Parameters of WTAC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dmax *, µm | Dav *, µm | LF *, % | |||

| Untreated samples [15] | - | 84.18 (19.40) | 43.31 (11.67) | 37.6 (18.8) | |

| Treated samples | PDADMAC LMW | - | 69.49 (14.06) | 43.37 (10.26) | 62.5 (14.2) |

| 0.01 M | 45.15 (15.90) | 28.24 (12.36) | 55.3 (14.8) | ||

| 0.1 M | 44.52 (18.13) | 24.98 (10.57) | 53.7 (20.3) | ||

| 0.5 M | 67.32 (22.90) | 43.10 (15.53) | 36.2 (17.4) | ||

| PDADMAC HMW | - | 76.02 (19.19) | 42.06 (11.91) | 54.8 (23.9) | |

| 0.01 M | 99.19 (37.57) | 49.78 (17.33) | 62.3 (21.6) | ||

| 0.1 M | 117.60 (26.00) | 60.10 (15.99) | 61.7 (17.6) | ||

| 0.5 M | 85.16 (34.34) | 39.26 (13.96) | 55.7 (21.6) | ||

| Samples | Adhesion Strength *, MPa |

|---|---|

| 1% PDADMAC LMW + 0.01 M | 3.04 (0.36) a |

| 1% PDADMAC LMW + 0.5 M | 3.08 (0.41) a |

| 1% PDADMAC LMW + 0.1 M | 3.21 (0.43) ab |

| 1% PDADMAC HMW + 0.1 M | 3.46 (0.37) bc |

| 1% PDADMAC LMW | 3.46 (0.39) bc |

| 1% PDADMAC HMW + 0.5 M | 3.48 (0.34) bc |

| Control samples | 3.54 (0.58) bc |

| 1% PDADMAC HMW + 0.01 M | 3.63 (0.49) c |

| 1% PDADMAC HMW | 3.72 (0.49) c |

| Samples | NaCl Concentration | Surface Roughness of Wood Coated with WTAC, µm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ra | Rz | Rt | |||

| Untreated samples [15] | - | 6.66 | 38.84 | 54.20 | |

| Treated samples | PDADMAC LMW | - | 5.19 by * | 30.55 bz * | 41.68 by * |

| 0.01 M | 3.71 ax * | 22.85 ax * | 32.24 ax * | ||

| 0.1 M | 3.92 ax * | 25.72 ay * | 32.83 ax * | ||

| 0.5 M | 3.98 ax * | 24.07 axy * | 31.23 ax * | ||

| PDADMAC HMW | - | 3.69 ax * | 22.99 ax * | 29.81 ax * | |

| 0.01 M | 4.15 ax * | 26.21 by * | 34.23 ay * | ||

| 0.1 M | 4.36 ax * | 27.47 byz * | 37.18 by * | ||

| 0.5 M | 5.21 by * | 29.39 bz * | 42.27 bz * | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Palija, T.; Djikanović, D.; Rančić, M.; Petrič, M.; Pavlič, M. Effects of PDADMAC Solution Pretreatment on Beech Wood—Waterborne Coating Interaction. Forests 2026, 17, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010148

Palija T, Djikanović D, Rančić M, Petrič M, Pavlič M. Effects of PDADMAC Solution Pretreatment on Beech Wood—Waterborne Coating Interaction. Forests. 2026; 17(1):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010148

Chicago/Turabian StylePalija, Tanja, Daniela Djikanović, Milica Rančić, Marko Petrič, and Matjaž Pavlič. 2026. "Effects of PDADMAC Solution Pretreatment on Beech Wood—Waterborne Coating Interaction" Forests 17, no. 1: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010148

APA StylePalija, T., Djikanović, D., Rančić, M., Petrič, M., & Pavlič, M. (2026). Effects of PDADMAC Solution Pretreatment on Beech Wood—Waterborne Coating Interaction. Forests, 17(1), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010148