Private Forest Owner Typology Based on Post-Disturbance Behaviour in Slovenia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Analytical Framework: Typologies and PFO Behavioural Response to Natural Disturbances

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

3.2. Cluster Analysis

3.3. Framework for Policy Instrument Development

4. Results

4.1. Basic Information on Private Forest Owners

4.2. Cluster Analysis Results

4.3. Policy Instruments Developed for Different PFO Types

5. Discussion

5.1. Typology Based on Post-Disturbance Behaviour

5.2. Policy Instruments in Relation to PFO Types

5.3. Methodological Challenges and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Variables | Outsourcing-Oriented Managers | Self-Reliant Managers | Less Active Managers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest property size | Outsourcing-oriented managers | 0.013 * | 0.012 * | |

| Self-reliant managers | 0.013 * | 0.996 | ||

| Less active managers | 0.012 * | 0.996 | ||

| Age | Outsourcing-oriented managers | 0.075 | 0.020 * | |

| Self-reliant managers | 0.075 | 0.697 | ||

| Less active managers | 0.020 * | 0.697 | ||

| Education | Outsourcing-oriented managers | 0.005 * | 0.038 * | |

| Self-reliant managers | 0.005 * | 0.291 | ||

| Less active managers | 0.038 * | 0.291 | ||

| Size of place of residence | Outsourcing-oriented managers | 0.001 * | 0.013 * | |

| Self-reliant managers | 0.001 * | 0.931 | ||

| Less active managers | 0.013 * | 0.931 | ||

| Hiring forestry contractors | Outsourcing-oriented managers | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | |

| Self-reliant managers | 0.000 * | 0.644 | ||

| Less active managers | 0.000 * | 0.644 | ||

| PFO performance of salvage logging | Outsourcing-oriented managers | 0.121 | <0.001 * | |

| Self-reliant managers | 0.121 | 0.001 * | ||

| Less active managers | <0.001 * | 0.001 * | ||

| Cooperation of PFOs in salvage logging | Outsourcing-oriented managers | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | |

| Self-reliant managers | <0.001 * | 0.015 * | ||

| Less active managers | <0.001 * | 0.015 * |

| Forest Management Objectives | Outsourcing-Oriented Managers | Self-Reliant Managers | Less Engaged Domestic Managers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forests are a place of rest or recreation | Outsourcing-oriented managers | 0.048 * | 0.000 * | |

| Self-reliant managers | 0.048 * | 0.000 * | ||

| Less active managers | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | ||

| Forests are important for mitigating climate change | Outsourcing-oriented managers | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | |

| Self-reliant managers | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | ||

| Less active managers | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | ||

| Forests are important for the preservation of biodiversity | Outsourcing-oriented managers | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | |

| Self-reliant managers | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | ||

| Less active managers | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | ||

| Forests are sources of wood and other forest products for personal consumption | Outsourcing-oriented managers | 0.000 * | 0.019 * | |

| Self-reliant managers | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | ||

| Less active managers | 0.019 * | 0.000 * | ||

| Forests are an important source of income through wood and other forest products | Outsourcing-oriented managers | 0.965 | 0.086 | |

| Self-reliant managers | 0.965 | 0.030 * | ||

| Less active managers | 0.086 | 0.030 * | ||

| Forests are an investment for the future, serving as a financial reserve | Outsourcing-oriented managers | 0.094 | 0.010 * | |

| Self-reliant managers | 0.094 | 0.000 * | ||

| Less active managers | 0.010 * | 0.000 * | ||

| Forests are spaces for the management of natural and cultural heritage | Outsourcing-oriented managers | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | |

| Self-reliant managers | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | ||

| Less active managers | 0.000 * | 0.000 * |

References

- Shorohova, E.; Aakala, T.; Gauthier, S.; Kneeshaw, D.; Koivula, M.; Ruel, J.C.; Ulanova, N. Natural Disturbances from the Perspective of Forest Ecosystem-Based Management. In Boreal Forests in the Face of Climate Change. Advances in Global Change Research, 1st ed.; Girona, M.M., Morin, H., Gauthier, S., Bergeron, Y., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 74, pp. 89–121. [Google Scholar]

- Patacca, M.; Lindner, M.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Cordonnier, T.; Fidej, G.; Gardiner, B.; Hauf, Y.; Jasinevičius, G.; Labonne, S.; Linkevičius, E.; et al. Significant increase in natural disturbance impacts on European forests since 1950. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2023, 29, 1359–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission: Joint Research Centre; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Durrant, T.; Boca, R.; Libertà, G.; Petroliagkis, T.; Di Leo, M.; Rodrigues, D.; Boccacci, F.; Schulte, E. Forest Fires in Europe, Middle East and North Africa 2022, 1st ed.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, M.; Diaci, J.; Kandare, K.; Krajnc, N.; Pisek, R.; Ščap, Š.; Stare, D.; Ogris, N. Private forest owner characteristics affect European spruce bark beetle management under an extreme weather event and host tree density. Forests 2021, 12, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senf, C.; Seidl, R. Storm and fire disturbances in Europe: Distribution and trends. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 3605–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidl, R.; Thom, D.; Kautz, M.; Martin-Benito, D.; Peltoniemi, M.; Vacchiano, G.; Wild, J.; Ascoli, D.; Petr, M.; Honkaniemi, J.; et al. Forest disturbances under climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverkus, A.B.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Thorn, S.; Gustafsson, L. Salvage logging in the world’s forests: Interactions between natural disturbance and logging need recognition. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018, 27, 1140–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, S.; Bässler, C.; Brandl, R.; Burton, P.J.; Cahall, R.; Campbell, J.L.; Castro, J.; Choi, C.Y.; Cobb, T.; Donato, D.C.; et al. Impacts of salvage logging on biodiversity: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverkus, A.B.; Benayas, J.M.R.; Castro, J.; Boucher, D.; Brewer, S.; Collins, B.M.; Donato, D.; Fraver, S.; Kishchuk, B.E.; Lee, E.-J.; et al. Salvage logging effects on regulating and supporting ecosystem services—A systematic map. Can. J. For. Res. 2018, 48, 983–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Noss, R.F.; Thorn, S.; Bässler, C.; Leverkus, A.B.; Lindenmayer, D. Increasing disturbance demands new policies to conserve intact forest. Conserv. Lett. 2019, 12, e12449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camia, A.; Giuntoli, J.; Jonsson, K.; Robert, N.; Cazzaniga, N.; Jasinevičius, G.; Avitabile, V.; Grassi, G.; Barredo Cano, J.I.; Mubareka, S. The Use of Woody Biomass for Energy Production in the EU; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnucan, W.H. Timber price dynamics after a natural disaster: Hurricane Hugo revisited. J. For. Econ. 2016, 25, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohngen, B.; Tian, X. Global climate change impacts on forests and markets. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 72, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeeva, E.; Wolfslehner, B.; Weber, N. 25 Years of EU Forest Policy—An Analysis. Forests 2025, 16, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirov, M.; Winkel, G.; Eckerberg, K. The coalitional politics of the European Union’s environmental forest policy: Biodiversity conservation, timber legality, and climate protection. Ambio 2021, 50, 2153–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Environment Agency. Climate-Resilient Forest Management. Climate-ADAPT, n.d. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/metadata/adaptation-options/climate-resilient-forest-management (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- European Commission. Guidelines on Closer-to-Nature Forest Management. 2023. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/publications/guidelines-closer-nature-forest-management_en (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- European Commission. New EU Forest Strategy for 2030. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=COM%3A2021%3A572%3AFIN (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/1991 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2024 on Nature Restoration and Amending Regulation (EU) 2022/869. Official Journal of the European Union, European Commission 2022. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1991/oj (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on a Monitoring Framework for Resilient European Forests. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=COM:2023:728:FIN (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Weiss, G.; Lawrence, A.; Hujala, T.; Lidestav, G.; Nichiforel, L.; Nybakk, E.; Quiroga, S.; Sarvašová, Z.; Suarez, C.; Živojinović, I. Forest ownership changes in Europe: State of knowledge and conceptual foundations. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 99, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichiforel, L.; Keary, K.; Deuffic, P.; Weiss, G.; Thorsen, B.J.; Winkel, G.; Avdibegović, M.; Dobšinská, Z.; Feliciano, D.; Gatto, P.; et al. How private are Europe’s private forests? A comparative property rights analysis. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Fries, C. The Knowledge and Value Basis of Private Forest Management in Sweden: Actual Knowledge, Confidence, and Value Priorities. Environ. Manag. 2020, 66, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilainen, A.; Lähdesmäki, M. Passive or not?—Examining the diversity within passive forest owners. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 151, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, R.; Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š.; Sotirov, M. Forest ownership, socioeconomic and geopolitical factors. In Europe’s Wood Supply in Disruptive Times, 1st ed.; Egger, C., Grima, N., Kleine, M., Radosavljevic, M., Eds.; International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO): Vienna, Austria, 2024; pp. 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Juutinen, A.; Tolvanen, A.; Koskela, T. Forest owners’ future intentions for forest management. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, K.; Bolte, A.; Haeler, E.; Haltia, E.; Jandl, R.; Juutinen, A.; Kuhlmey, K.; Lidestav, G.; Mäkipää, R.; Rosenkranz, L.; et al. Forest values and application of different management activities among small-scale forest owners in five EU countries. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 146, 102881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, M.; Morel, L.; Fournier, M. Developing the persona method to increase the commitment of non-industrial private forest owners in French forest policy priorities. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 126, 102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlman, J.; Berghäll, S.; Hurttala, H.; Vainio, A. Understanding the diversity of objectives among women forest owners in Finland. Can. J. For. Res. 2022, 52, 1367–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiebel, M.; Mölder, A.; Bieling, C.; Hansen, P.; Plieninger, T. Understanding small-scale private forest owners is a basis for transformative change towards integrative conservation. People Nat. 2024, 6, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekström, H.; Danley, B.; Clough, Y.; Droste, N. Barking up the wrong tree?—A guide to forest owner typology methods. For. Policy Econ. 2024, 163, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficko, A.; Lidestav, G.; Ní Dhubháin, Á.; Karppinen, H.; Živojinović, I.; Westin, K. European private forest owner typologies: A review of methods and use. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 99, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, D.; Bouriaud, L.; Brahic, E.; Deuffic, P.; Dobsinska, Z.; Jarsky, V.; Lawrence, A.; Nybakk, E.; Quiroga, S.; Suarez, C.; et al. Understanding private forest owners’ conceptualisation of forest management: Evidence from a survey in seven European countries. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirov, M.; Sallnäs, O.; Eriksson, L.O. Forest owner behavioral models, policy changes, and forest management. An agent-based framework for studying the provision of forest ecosystem goods and services at the landscape level. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 103, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, J.; Poljanec, A. Trenutne aktivnosti in izzivi pri preprečevanju škod v gozdovih zaradi ekstremnih vremenskih pojavov. In Gozd in les kot Priložnost za Regionalni Razvoj: Festival Lesa, Kočevje, 1st ed.; Bončina, A., Oven, P., Eds.; Biotechnical Faculty: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2019; Volume 164, pp. 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Slovenia Forest Service. Report of Slovenia Forest Service about Forests for 2023, 1st ed.; Slovenia Forest Service: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2024; Available online: http://www.zgs.si/fileadmin/zgs/main/img/PDF/LETNA_POROCILA/PorGOZD_za_leto_2023.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Štraus, H.; Bončina, A. The vulnerability of four main tree species in European forests to seven natural disturbance agents: Lessons from Slovenia. Eur. J. For. Res. 2025, 144, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Act (Zakon o Gozdovih). Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, vol 30/93, 56/99—ZON, 67/02, 110/02—ZGO-1, 115/06—ORZG40, 110/07, 106/10, 63/13, 101/13—ZDavNepr, 17/14, 22/14—odl. US, 24/15, 9/16—ZGGLRS and 77/16, 1993. Available online: http://www.pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO270# (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Resolution on National Forest Programme (Resolucija o Nacionalnem Gozdnem Programu). Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia vol 111/07. 2007. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=RESO56 (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Who Owns our Forests? Forest Ownership in the ECE Region; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gossum, P.; Arts, B.; Verheyen, K. From “smart regulation” to “regulatory arrangements”. Policy Sci. 2010, 43, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunningham, N.; Grabosky, P. Smart Regulation: Designing Environmental Policy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gossum, P.; Arts, B.; Verheyen, K. “Smart regulation”: Can policy instrument design solve forest policy aims of expansion and sustainability in Flanders and the Netherlands? For. Policy Econ. 2012, 16, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidestav, G.; Westin, K. The Impact of Swedish Forest Owners’ Values and Objectives on Management Practices and Forest Policy Accomplishment. Small-Scale For. 2023, 22, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuffic, P.; Sotirov, M.; Arts, B. “Your policy, my rationale”. How individual and structural drivers influence European forest owners’ decisions. Land Use policy 2018, 79, 1024–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stare, D.; Ščap, Š.; Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. Factors Influencing Private Forest Owners Decision-Making Rationalities to Implement Salvage Logging after Large-Scale Natural Disturbances in Slovenia. Croat. J. For. Eng. 2025, 46, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petucco, C.; Andrés-Domenech, P.; Duband, L. Cut or keep: What should a forest owner do after a windthrow? For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 461, 117866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanginés de Cárcer, P.; Mederski, P.S.; Magagnotti, N.; Spinelli, R.; Engler, B.; Seidl, R.; Eriksson, A.; Eggers, J.; Bont, L.G.; Schweier, J. The Management Response to Wind Disturbances in European Forests. Curr. For. Rep. 2021, 7, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, J.R.; Butler, B.J.; Borsuk, M.E.; Markowski-Lindsay, M.; MacLean, M.G.; Thompson, J.R. Using the theory of planned behavior to understand family forest owners’ intended responses to invasive forest insects. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2021, 34, 1001–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, S.; Chao, A.; Georgiev, K.B.; Müller, J.; Bässler, C.; Campbell, J.L.; Castro, J.; Chen, Y.-H.; Choi, C.-Y.; Cobb, T.P.; et al. Estimating retention benchmarks for salvage logging to protect biodiversity. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoke, T.; Baeumer, B.; Härtl, F.; Paul, C.; Tränkner, J. Economic losses from natural disturbances in Norway spruce forests—A quantification using Monte-Carlo simulations. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 185, 107046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stare, D.; Grošelj, P.; Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. Decision Support Framework for Evaluating The Barriers to Salvage Logging: A Case Study on Private Forest Management in Slovenia. Environ. Manag. 2023, 71, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š.; Nonić, D.; Glavonjić, P.; Nedeljković, J.; Avdibegović, M.; Krč, J. Private Forest Owner Typologies in Slovenia and Serbia: Targeting Private Forest Owner Groups for Policy Implementation. Small-Scale For. 2015, 14, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0; IBM Corp.: Westchester County, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stare, D.; Grošelj, P.; Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. Ovire in rešitve pri sanaciji v ujmah poškodovanih zasebnih gozdov. Acta Silvae Ligni 2020, 123, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stare, D.; Grošelj, P.; Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. A framework to Overcome Challenges in Salvage Logging After Natural Disturbances: A Case Study on Private Forest Owners in Slovenia. Slovenian Forestry Institute: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2025; manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Kuuluvainen, T.; Angelstam, P.; Frelich, L.E.; Jõgiste, K.; Koivula, M.; Kubota, Y.; Lafleur, B.; Macdonald, E. Natural disturbance-based forest management: Moving beyond retention and continuous-cover forestry. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2021, 4, 629020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.; Sharma, A.; Stein, T.; Vogel, J.; Nowak, J. Forest Disturbances and Nonindustrial Forest Landowners: Management of Invasive Plants, Fire Hazards and Wildlife Habitats After a Hurricane. J. For. 2023, 121, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josset, C.; Shanafelt, D.W.; Abildtrup, J.; Stenger, A. Probabilistic typology of private forest owners: A tool to target the development of new market for ecosystem services. Land Use Policy 2023, 134, 106935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverkus, A.B.; Thorn, S.; Gustafsson, L.; Noss, R.; Müller, J.; Pausas, J.G.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Environmental policies to cope with novel disturbance regimes—Steps to address a world scientists’ warning to humanity. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 021003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riguelle, S.; Hébert, J.; Jourez, B. Integrated and systemic management of storm damage by the forest-based sector and public authorities. Ann. For. Sci. 2016, 73, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikinmaa, L.; de Koning, J.H.C.; Derks, J.; Grabska-Szwagrzyk, E.; Konczal, A.A.; Lindner, M.; Socha, J.; Muys, B. The priorities in managing forest disturbances to enhance forest resilience: A comparison of a literature analysis and perceptions of forest professionals. For. Policy Econ. 2024, 158, 103119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danley, B. Forest owner objectives typologies: Instruments for each owner type or instruments for most owner types? For. Policy Econ. 2019, 105, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, P.; Rost, J.; Tobella, C.; Puig-Gironès, R.; Bas, J.M.; Franch, M.; Mauri, E. Towards better practices of salvage logging for reducing the ecosystem impacts in Mediterranean burned forests. iForest 2020, 13, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonen, P.; Miettinen, J.; Haara, A.; Matala, J.; Hujala, T.; Mehtätalo, L.; Pappinen, A. Does cooperation between Finnish forest owners increase their interest in Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) lekking site management? Soc. Nat. Resour. 2022, 35, 1189–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttilainen, H.; Hallikainen, V.; Miina, J.; Vornanen, J.; Vanhanen, H. Forest Owners’ Perspectives Concerning Non-Timber Forest Products, Everyman’s Rights, and Organic Certification of Forests in Eastern Finland. Small-Scale For. 2023, 22, 69–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories |

|---|---|

| Past management activity | 1—Without experience 2—With experience |

| Hiring forestry contractors | 1—No (without experience) 2—Yes (with experience) |

| PFO performance of salvage logging | 1—Yes, in accordance with the salvage logging deadlines determined by the Slovenia Forest Service 2—Yes, but after the salvage logging deadlines determined by the Slovenia Forest Service 3—I did not perform the salvage logging |

| Cooperation of PFOs in salvage logging | 1—Yes 2—No |

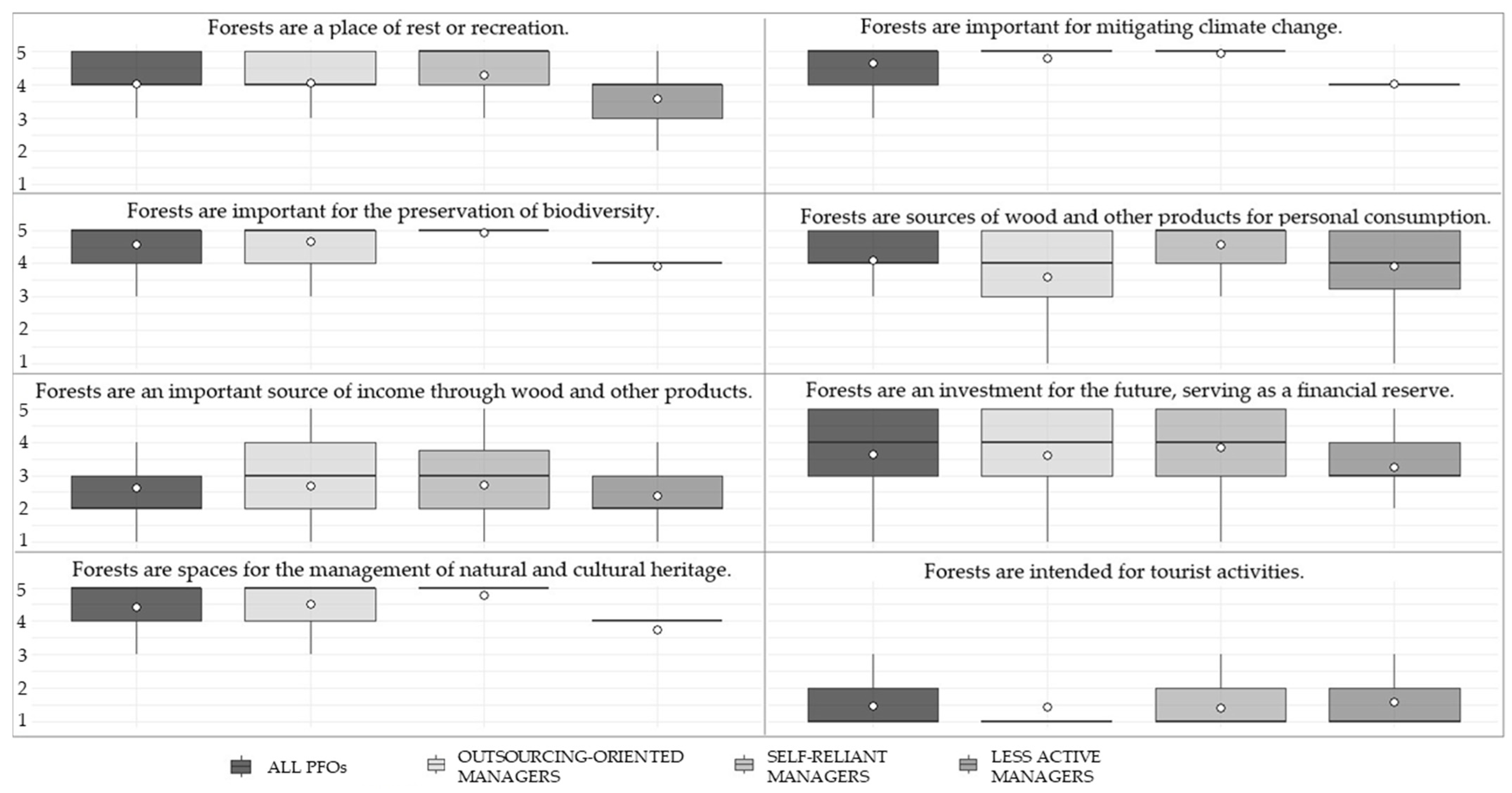

| Forests are a place of rest or recreation. | PFO agreement with the statements that define the management objectives and motives of their forest 1—I do not agree at all 2—I do not agree 3—I neither agree nor disagree 4—I agree 5—I completely agree |

| Forests are important for mitigating climate change. | |

| Forests are important for the preservation of biodiversity. | |

| Forests are sources of wood and other forest products for personal consumption. | |

| Forests are an important source of income through wood and other forest products. | |

| Forests are an investment for the future, serving as a financial reserve. | |

| Forests are spaces for the management of natural and cultural heritage. | |

| Forests are intended for tourist activities. |

| Total Sample | Group Outsourcing-Oriented Managers | Group Self-Reliant Managers | Group Less Active Managers | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of units | 547 | 175 | 230 | 142 | ||

| Share (%) | 32.0 | 42.0 | 26.0 | |||

| Basic characteristics of PFOs within groups | ||||||

| Forest property size (ha) | Mean | 9.1 | 13.9 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 0.011 *,1 |

| Std. deviation | 19.7 | 27.5 | 15.5 | 12.6 | ||

| Gender (%) | Male | 60.1 | 62.3 | 56.1 | 64.1 | 0.242 2 |

| Female | 39.9 | 37.7 | 43.9 | 35.9 | ||

| Age (years) | Mean | 53.6 | 55.9 | 52.9 | 51.7 | 0.018 *,1 |

| Std. Deviation | 13.8 | 13.8 | 13.6 | 13.7 | ||

| Occupation (%) | Work inactive (housewife, student, unemployed, retired) | 43.6 | 44.8 | 43.0 | 43.0 | 0.991 2 |

| Work active (employed, self-employed) | 55.9 | 54.6 | 56.5 | 56.3 | ||

| Insured as farmer | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.7 | ||

| Education (%) | Elementary school or less | 3.5 | 3.5 | 4.8 | 1.4 | 0.010 *,2 |

| High school | 48.3 | 37.4 | 53.9 | 52.8 | ||

| Bachelor’s education or more | 48.2 | 59.2 | 41.2 | 45.8 | ||

| Size of place of residence (%) | <3000 inhabitants | 57.8 | 46.3 | 63.3 | 62.0 | 0.003 *,2 |

| 3000–10,000 | 23.6 | 27.4 | 21.3 | 22.5 | ||

| >10,000 inhabitants | 18.6 | 26.3 | 14.8 | 15.5 | ||

| Variables used as a basis for the typology | ||||||

| Past management activity (%) | Without experience | 7.3 | 2.9 | 7.8 | 12.0 | 0.587 2 |

| With experience | 92.7 | 97.1 | 92.2 | 88.0 | ||

| Hiring forestry contractors (%) | No | 61.1 | 7.4 | 87.0 | 85.2 | <0.001 *,2 |

| Yes | 38.9 | 92.6 | 13.0 | 14.8 | ||

| PFO performance of salvage logging (%) | Yes (within the deadlines) | 80.4 | 83.4 | 84.8 | 69.7 | <0.001 *,2 |

| Yes (after deadlines) | 10.2 | 12.6 | 7.8 | 11.3 | ||

| Do not perform | 9.3 | 4.0 | 7.4 | 19.0 | ||

| Cooperation of PFOs in salvage logging (%) | Yes | 40.0 | 94.3 | 10.9 | 20.4 | <0.001 *,2 |

| No, alone or with family help | 60.0 | 5.7 | 89.1 | 79.6 | ||

| Forests are a place of rest or recreation. | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 0.010 *,3 | |

| Forests are important for mitigating climate change. | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.0 | <0.010 *,1 | |

| Forests are important for the preservation of biodiversity. | 4.6 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 3.9 | <0.010 *,1 | |

| Forests are sources of wood and other forest products for personal consumption. | 4.1 | 3.6 | 4.6 | 3.9 | <0.010 *,1 | |

| Forests are an important source of income through wood and other forest products. | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 0.024 *,1 | |

| Forests are an investment for the future, serving as a financial reserve. | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 3.3 | <0.010 *,1 | |

| Forests are spaces for the management of natural and cultural heritage. | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 3.8 | <0.010 *,1 | |

| Forests are intended for tourist activities. | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.062 3 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stare, D.; Uhan, Z.; Triplat, M.; Ščap, Š.; Krajnc, N.; Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. Private Forest Owner Typology Based on Post-Disturbance Behaviour in Slovenia. Forests 2025, 16, 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16060949

Stare D, Uhan Z, Triplat M, Ščap Š, Krajnc N, Pezdevšek Malovrh Š. Private Forest Owner Typology Based on Post-Disturbance Behaviour in Slovenia. Forests. 2025; 16(6):949. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16060949

Chicago/Turabian StyleStare, Darja, Zala Uhan, Matevž Triplat, Špela Ščap, Nike Krajnc, and Špela Pezdevšek Malovrh. 2025. "Private Forest Owner Typology Based on Post-Disturbance Behaviour in Slovenia" Forests 16, no. 6: 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16060949

APA StyleStare, D., Uhan, Z., Triplat, M., Ščap, Š., Krajnc, N., & Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. (2025). Private Forest Owner Typology Based on Post-Disturbance Behaviour in Slovenia. Forests, 16(6), 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16060949