Forest Education: Past, Present, and Future

Abstract

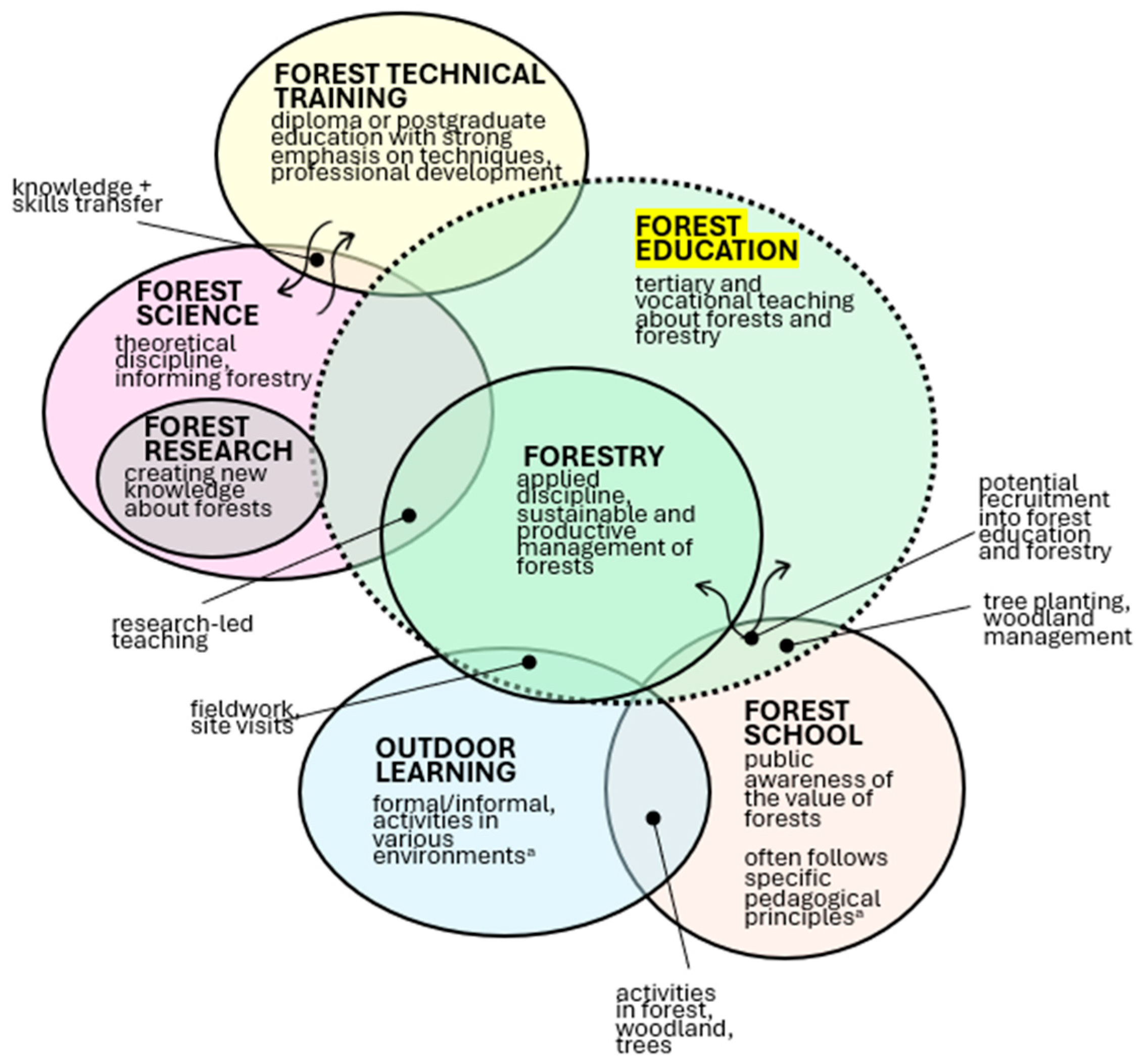

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Forest Education: The Past

3.1. Historical Context by Continent or Region

3.2. Europe

3.3. North America

3.4. Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC)

3.5. Africa

3.6. Asia and the Pacific

4. Forest Education: The Present

4.1. Europe

4.2. North America

4.3. Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC)

4.4. Africa

4.5. Asia and Pacific

5. Forest Education: The Future

5.1. Forest Education During a Time of Uncertainty

5.2. The Social and Multidisciplinary Dimensions of Forest Education

5.3. Human Diversity in Forest Education

5.4. Making Changes in Forest Education in Response to New Opportunities

- (a)

- There are substantial variations in the curriculum across institutions (even within the same nation), as well as over time. Some variation among institutions could be a function of their traditions, which in turn might be related to the age of establishment (see Table 1). Institutions rightly have autonomy, though they are also influenced by national priorities (e.g., communicated from governments), accrediting bodies, and market forces (e.g., recruitment, student supply and demand, and employability).

- (b)

- The summary table is not intended to be prescriptive. It is safer to describe more generic curriculum content, which is likely to apply across a range of institutions. In any case, there are arguments that the ‘past’ curriculum might have some charm, but it is not likely to feel very relevant. Similarly, inevitably, there will be uncertainty about the future, and our speculation needs to be cautious.

5.5. Recommendations from This Review

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilenius, K.; Rekola, M.; Nevgi, A.; Sandström, N. How is it Covered? —A Global Perspective on Teaching Themes and Perceived Gaps and Availability of Resources in University Forestry Education. Forests 2024, 15, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegatheswaran, R.; Florin, I.; Hazirah, A.L.; Shukri, M.; Latib, A.; Research, F.; Malaysia, I.; Al, H. Transforming Forest Education to Meet the Changing Demands for Professionals. J. Trop. For. Sci. 2018, 30, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjølie, H.K.; Lauritzen, T.; Akin, D. Unveiling Multiple Pathways into Tertiary Forestry Education: A Mixed-Method Study. Scand. J. For. Res. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, C.L. Forestry Education that Goes Beyond the Standard and Unoriginal. Aust. For. 2019, 82, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekola, M.; Shari, T.L. Global Assessment of Forest Education Creation of a Global Forest Education Platform and Launch of a Joint Initiative Under the Aegis of the Collaborative Partnership on Forests (FAO-ITTO-IUFRO Project GCP /GLO/044/GER); Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2022; Volume 32, pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.F. Broader and Deeper: The Challenge of Forestry Education in the Late 20th Century. J. For. 1996, 94, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.L. Multidisciplinarity, Interdisciplinarity and Training in Forestry and Forest Research. For. Chron. 2005, 81, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himes, A.; Dues, K. Relational Forestry: A Call to Expand the Discipline’s Institutional Foundations. Ecosyst. People 2024, 20, 2365236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luloff, A.E. Regaining Vitality in the Forestry Profession: A Sociologist’s Perspective. J. For. 1995, 93, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, F.; Brandt, M.; Tong, X.; Skole, D.; Kariryaa, A.; Ciais, P.; Davies, A.; Hiernaux, P.; Chave, J.; Mugabowindekwe, M.; et al. More than One Quarter of Africa’s Tree Cover is found Outside Areas Previously Classified as Forest. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, D.; Stephens, M. Planted Forest Development in Australia and New Zealand: Comparative Trends and Future Opportunities. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 2014, 44, S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payn, T.; Carnus, J.; Freer-Smith, P.; Kimberley, M.; Kollert, W.; Liu, S.; Orazio, C.; Rodriguez, L.; Silva, L.N.; Wingfield, M.J. Changes in Planted Forests and Future Global Implications. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 352, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanowski, P. Forestry Education in a Changing Landscape. Int. For. Rev. 2001, 3, 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard, S.H. Forestry Curricula for the 21st Century—Maintaining Rigor, Communicating Relevance, Building Relationships. J. For. 2015, 113, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K. Beyond Forestry Education. For. Sci. Technol. 2005, 1, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancura, K. Challenging Issues and Future Strategies of Forest Research and Education in Central and Eastern European Countries. For. Sci. Technol. 2010, 1, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Royal Forestry Society. What’s in A Name—Forest Education, Outdoor Learning, and Forest School, 2021. Available online: https://rfs.org.uk/fene/whats-in-a-name/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- O’hara, K.L.; Salwasser, H. Forest Science Education in Research Universities. J. For. 2015, 113, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garden, A.; Downes, G. New Boundaries, Undecided Roles: Towards an Understanding of Forest Schools as Constructed Spaces. Education 3–13 2024, 52, 1542–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.; Riaz, S.; Rashid, M.H.U.; Khan, H.; Ahmad, I.; Asif, M.; Sahar, R. Forestry Holistic Education. In Revitalizing the Learning Ecosystem for Modern Students; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 168–190. [Google Scholar]

- Sample, A.R.; Bixler, P.; McDonough, M.H.; Bullard, S.H.; Snieckus, M.M. The Promise and Performance of Forestry Education in the United States: Results of a Survey of Forestry Employers, Graduates, and Educators. J. For. 2015, 113, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample, V.A.; Ringold, P.C.; Block, N.E.; Giltmier, J.W. Forestry Education: Adapting to the Changing Demands on Professionals. J. For. 1999, 97, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, H.A.; Svenning, J.; Saxena, A.; Muscarella, R.; Franklin, J.; Garbelotto, M.; Mathews, A.S.; Saito, O.; Schnitzler, A.E.; Serra-Diaz, J.M.; et al. History as Grounds for Interdisciplinarity: Promoting Sustainable Woodlands via an Integrative Ecological and Socio-Cultural Perspective. One Earth 2021, 4, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L.; Brancalion, P.H.S.; Laestadius, L.; Bennett-Curry, A.; Buckingham, K.; Kumar, C.; Moll-Rocek, J.; Vieira, I.C.G.; Wilson, S.J. When is a Forest a Forest? Forest Concepts and Definitions in the Era of Forest and Landscape Restoration. Ambio 2016, 45, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.L.C.; Kuchma, O.; Krutovsky, K.V. Mixed-Species Versus Monocultures in Plantation Forestry: Development, Benefits, Ecosystem Services and Perspectives for the Future. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2018, 15, e00419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockerhoff, E.G.; Barbaro, L.; Castagneyrol, B.; Forrester, D.I.; Gardiner, B.; González-Olabarria, J.R.; Lyver, P.O.; Meurisse, N.; Oxbrough, A.; Taki, H.; et al. Forest Biodiversity, Ecosystem Functioning and the Provision of Ecosystem Services. Biodivers. Conserv. 2017, 26, 3005–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernow, B.E. A Brief History of Forestry in Europe, the United States and Other Countries, 2nd ed.; University Press: Toronto, ON, USA, 1911; pp. 1–506. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, S.; Lippe, R.S.; Schweinle, J. Informal Employment in the Forest Sector: A Scoping Review. Forests 2022, 13, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croom, D.B. The Biltmore Forest School and the Establishment of Forestry Education in America. J. Res. Tech. Careers 2024, 8, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia Contributors. List of Forestry Universities and Colleges [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; 2025 Nov 9, 22:28 UTC [cited 2025 Nov 27]. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_forestry_universities_and_colleges&oldid=1321320510 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Mucina, L. Biome: Evolution of a Crucial Ecological and Biogeographical Concept. New Phyt. 2019, 222, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplyakov, V.K. Forestry Education in Russia. For. Chron. 1994, 70, 700–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Beanblossom, R. Biltmore -the Beginning of Forestry Education in America. Bioscience 2003, 118, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogh, B. Scientific Forestry and the Roots of the Modern American State: Gifford Pinchot’s Path to Progressive Reform. Environ. Hist. 2002, 7, 198–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldin, R.W.; Brown, P. Forest Education and Research in the United States of America. For. Sci. Technol. 2005, 1, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sharik, T.L.; Lilieholm, R.J.; Lindquist, W.; Richardson, W.W. Undergraduate Enrollment in Natural Resource Programs in the United States: Trends, Drivers, and Implications for the Future of Natural Resource Professions. J. For. 2015, 113, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefer, M.J.; Finley, J.C.; Luloff, A.E.; Mcdill, M.E. Understanding Loggers’ Perceptions. J. Sustain. For. 2003, 17, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigg, C. Lessons from Yesterday’s Foresters. J. For. 2021, 120, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufty, M. A Political Ecology of Latin American Forests Through Time. In Latin America 1810–2010; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2014; pp. 241–267. [Google Scholar]

- Deloughrey, E.; Handley, G.B.; Paravisini-Gebert, L. Deforestation and the Yearning for Lost Landscapes in Caribbean Literatures. In Postcolonial Ecologies: Literatures of the Environment; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, R.A.; Lefkowitz, D.S.; Skole, D.L. Changes in the Landscape of Latin America between 1850 and 1985 I. Progressive Loss of Forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 1991, 38, 143–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pereda, I. Forestry Science in Argentina through the Figure of Lucas Tortorelli, 1936–1972. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- González Hernández, G. Forest High Education Programs Implemented in Selected Latin America Countries. Stud. Mater. Cent. Nat. For. Educ. Rogów 2012, 31, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Temu Per, A.B.; Rudebjer, G.; Kiyiapi, J.; Van Lierop, P. Forestry Education in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia: Trends, Myths and Realities; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2005; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Legilisho-Kiyiapi, D.J. The State of Forest Education in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Forestry Policy and Institutions Working Paper; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2014; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, B.M. The Rise and Demise of South Africa’s First School of Forestry. Environ. Hist. 2013, 19, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temu, A.B.; Okali, D.; Bishaw, B. Forestry Education, Training and Professional Development in Africa. Int. For. Rev. 2006, 8, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandergeest, P.; Peluso, N.L. Empires of Forestry: Professional Forestry and State Power in Southeast Asia, Part 1. Environ. Hist. 2006, 12, 31–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanowski, P.; Edwards, P. Forests Under the Southern Cross: The Forest Environmental Frontier in Australia and New Zealand. Ambio 2021, 50, 2183–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, M.M.; Dargavel, J. Imperial Ethos, Dominions Reality: Forestry Education in New Zealand and Australia, 1910–1965. Environ. Hist. 2008, 14, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, I. Forestry Education in Australia the Challenges of Change. N. Z. J. For. 2013, 58, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, K.; Corbin, C.; Diver, S.; Eitzel, M.V.; Williamson, J.; Brashares, J.S.; Fortmann, L. Finding Your Way in the Interdisciplinary Forest: Notes on Educating Future Conservation Practitioners. Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 23, 3405–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudebjer, P.G.; Siregar, I. Trends in Forestry Education in Southeast Asia and Africa. Unasylva 2004, 55, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, A.S.; Lertzman, K.P.; Gustafsson, L. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in Forest Ecosystems: A Research Agenda for Applied Forest Ecology. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 54, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekola, M.; Taber, A.B.; Sharik, T.L.; Parrotta, J.A.; Dockry, M.J.; Babalola, F.D.; Bal, T.L.; Ganz, D.; Gruca, M.; Guariguata, M.R.; et al. Social and Knowledge Diversity in Forest Education: Vital for the World’s Forests. Ambio 2024, 54, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichecki, D.; Weinbrenner, H.; Bethmann, S. Becoming a Forester. Exploring Forest Management Students’ Habitus in the Making. For. Policy Econ. 2024, 172, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mook, A.; Dwivedi, P. Exploring Links between Education, Forest Management Intentions, and Economic Outcomes in Light of Gender Differences in the United States. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 145, 102861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redelsheimer, C.L.; Boldenow, R.; Marshall, P. Adding Value to the Profession: The Role of Accreditation. J. For. 2015, 113, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walentowski, H.; Kietz, B.; Horsch, J.; Linkugel, T.; Viöl, W. Development of an Interdisciplinary Master of Forestry Program Focused on Forest Management in a Changing Climate. Forests 2020, 11, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.B. Landscape Change and the Science of Biodiversity Conservation in Tropical Forests: A View from the Temperate World. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 2405–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tew, E.R.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Beatty, M.; Büntgen, U.; Butterworth, H.; Clover, G.; Cook, D.; Dauksta, D.; Day, W.; Deakin, J.; et al. A Horizon Scan of Issues Affecting UK Forest Management within 50 Years. For. Int. J. For. Res. 2024, 97, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialic-Murphy, L.; Mcelderry, R.M.; Esquivel-Muelbert, A.; Van Den Hoogen, J.; Zuidema, P.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Almeida De Oliveira, E.; Alvarez Loayza, P.; Alvarez-Davila, E.; Alves, L.F.; et al. The Pace of Life for Forest Trees. Science 2024, 386, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhris, I.; Marano, G.; Dalmonech, D.; Valentini, R.; Collalti, A. Modeling Forest Growth Under Current and Future Climate. Curr. For. Rep. 2025, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condit, R.; Lao, S.; Singh, A.; Esufali, S.; Dolins, S. Data and Database Standards for Permanent Forest Plots in a Global Network. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 316, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.R.; Schaffer-Morrison, S. Forests of the Future: The Importance of Tree Seedling Research in Understanding Forest Response to Anthropogenic Climate Change. Tree Physiol. 2024, 44, tpae039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilliam, F.S. Forest Ecosystems of Temperate Climatic Regions: From Ancient use to Climate Change. New Phytol. 2016, 212, 871–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokowska-Paluszak, M.; Wierzbicka, A.; Łukowski, A.; Gruchała, A.; Sagan, J.; Skorupski, M. Attitudes Towards Foresters in Polish Society. Forests 2022, 13, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N. Critical Review of Forestry Education. Biosci. Educ. 2003, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, S.H.; Stephens Williams, P.; Coble, T.; Coble, D.W.; Darville, R.; Rogers, L. Producing ‘Society-Ready’ Foresters: A Research Based Process to Revise the Bachelor of Science in Forestry Curriculum at Stephen F. Austin State University. J. For. 2014, 112, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluch, M. Forest Pedagogy Towards the Problem of Polish Educational Monoculture: Projective Pilot Studies. Stud. Ecol. Bioethicae 2023, 21, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durusoy, İ.; Bahçeci Öztürk, Y. What are Foresters Taught? an Analysis of Undergraduate Level Forestry Curricula in Türkiye. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvarts, E.A.; Karpachevskiy, M.L.; Shmatkov, N.M.; Baybar, A.S. Reforming Forest Policies and Management in Russia: Problems and Challenges. Forests 2023, 14, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowasch, M.; Oettel, J.; Bauer, N.; Lapin, K. Forest Education as Contribution to Education for Environmental Citizenship and Non-Anthropocentric Perspectives. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaksonen-Craig, S. The Determinants of Foreign Direct Investments in Latin American Forestry and Forest Industry. J. Sustain. For. 2008, 27, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, A. Latin-American-and-Caribbean-Forests-in-the-2020s-Trends-Challenges-and-Opportunities: Foreword; Inter-American Development Bank (IDB): Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Piñeros, S. Regional Assessment of Forest Education in Latin America and the Caribbean; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2021; pp. 1–124. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Pastur, G.J.; Roig, F.A. Current Trends in Forestry Research of Latin-America: An Editorial Overview of the Special Issue. Ecol. Process. 2024, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakamada, R.; Frosini De Barros Ferraz, S.; Moré Mattos, E.; Sulbarán-Rangel, B. Trends in Brazil’s Forestry Education: Overview of the Forest Engineering Programs. Forests 2023, 14, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zubair, M.; Jamil, A.; Lukac, M.; Manzoor, S.A. Non-Timber Forest Products Collection Affects Education of Children in Forest Proximate Communities in Northeastern Pakistan. Forests 2019, 10, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, Q.; Zong, B. Visualization of Forest Education using CiteSpace: A Bibliometric Analysis. Forests 2025, 16, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, I.; Brukas, V. Training Forestry Students for Uncertainty and Complexity: The Development and Assessment of a Transformative Roleplay. Int. For. Rev. 2024, 26, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aouri, Z. Higher Education in a VUCA-Driven World. the Need for 21st Century Skills. Rev. Linguist. Réf. Intercult. 2024, 2024, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hepper, J. Making Change Visible—An Explorative Case Study of Dealing with Climate Change Deniers in Forest Education. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2021, 23, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himes, A.; Bauhus, J.; Adhikari, S.; Barik, S.K.; Brown, H.; Brunner, A.; Burton, P.J.; Coll, L.; D’amato, A.W.; Diaci, J.; et al. Forestry in the Face of Global Change: Results of a Global Survey of Professionals. Curr. For. Rep. 2023, 9, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waeber, P.O.; Melnykovych, M.; Riegel, E.; Chongong, L.V.; Lloren, R.; Raher, J.; Reibert, T.; Zaheen, M.; Soshenskyi, O.; Garcia, C.A. Fostering Innovation, Transition, and the Reconstruction of Forestry: Critical Thinking and Transdisciplinarity in Forest Education with Strategy Games. Forests 2023, 14, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yu, P.; Wang, M.; Chen, H.; Nawaz, M.; Liu, X. Integration and Evaluation of SLAM-Based Backpack Mobile Mapping System. E3S Web Conf. 2025, 206, 03014. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyiapi, J.O. Foreword: New Perspectives in Forest Education. In Proceedings of the First Global Workshop on Forestry Education, Nairobi, Kenya, 25–27 September 2007; ICRAF: Nairobi, Kenya, 2007; pp. 1–493. [Google Scholar]

- Vonhof, S. Deficiencies of Undergraduate Forestry Curricula in their Social Sciences and Humanities Requirements. J. For. 2010, 108, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larasatie, P.; Jones, E.; Hansen, E.; Lewark, S. A Wake-Up Call? A Review of Inequality Based on the Forest-Related Higher Education Literature. Environ. Sci. Amp. Policy 2024, 162, 103942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Mallen, I.; Barraza, L. Are Adolescents from a Forest Community Well-Informed about Forest Management? J. Biol. Educ. 2008, 42, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, M.S.; Costanza, K.K.L.; Zukswert, J.M.; Kenefic, L.S.; Leahy, J.E. An Adaptive and Evidence-Based Approach to Building and Retaining Gender Diversity within a University Forestry Education Program: A Case Study of SWIFT. J. For. 2020, 118, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewoń, R.; Pirożnikow, E. Getting to Know the Potential of Social Media in Forest Education. For. Res. Pap. 2019, 80, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Putz, F. Are You a Conservationist or a Logging Advocate? In Working Forests in the Neotropics; Zarin, D., Alavalapati, J., Putz, F., Schmink, M., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, C.; Wingfield, M.J. Challenges and Strategies Facing Forest Research and Education for the 21st Century: A Case Study from South Africa. For. Sci. Technol. 2010, 1, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilanes Montoya, A.V.; Castillo Vizuete, D.D.; Marcu, M.V. Exploring the Role of ICTs and Communication Flows in the Forest Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, E.M.; Blinn, C.R. How Will COVID-19 Change Forestry Education? A Study of US Forest Operations Instructors. J. For. 2021, 120, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Piñeros, S.; Walji, K.; Rekola, M.; Owuor, J.A.; Lehto, A.; Tutu, S.A.; Giessen, L. Innovations in Forest Education: Insights from the Best Practices Global Competition. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexer, M.J.; Bravo, F.; Yang, S.; Ruano, I.; Ant Ón-Fern Ández, C.; Herrero, C.; Án Durango, I. Editorial: Artificial Intelligence and Forestry. Front. For. Glob. Change 2024, 7, 1500701. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, C.H.; Borchetta, C.; Anderson, D.L.; Arellano, G.; Barker, M.; Charron, G.; Lamontagne, J.M.; Richards, J.H.; Abercrombie, E.; Banin, L.F.; et al. Extending our Scientific Reach in Arboreal Ecosystems for Research and Management. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 4, 712165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačovič, P.; Pirník, R.; Kafková, J.; Michálik, M.; Kanáliková, A.; Kuchár, P. Satellite-Based Forest Stand Detection using Artificial Intelligence. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 10898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanmohammadi, S.; Cruz, M.G.; Perrakis, D.D.B.; Alexander, M.E.; Arashpour, M. Using AutoML and Generative AI to Predict the Type of Wildfire Propagation in Canadian Conifer Forests. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- César De Lima Araújo, H.; Silva Martins, F.; Tucunduva Philippi Cortese, T.; Locosselli, G.M. Artificial Intelligence in Urban forestry—A Systematic Review. Urban For. Urban Green 2021, 66, 127410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Jiang, D. AI-Powered Plant Science: Transforming Forestry Monitoring, Disease Prediction, and Climate Adaptation. Plants 2025, 14, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications in Forest Management and Biodiversity Conservation. Nat. Resour. Conserv. Res 2023, 6, 3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, G. International Trends in Forestry Education. N. Z. J. For. 2013, 58, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nyland, R.D. The Decline in Forestry Education Enrollment -some Observations and Opinions La Disminución De La Matrícula En Educación Forestal -Algunas Observaciones Y Opiniones. Bosque 2008, 29, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, G. Empire Forestry and the Origins of Environmentalism. J. Hist. Geogr. 2001, 27, 529–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year Established | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global region | Total number of institutes | Country with most institutes | Earliest | Latest | Median year |

| N America | 60 | USA | 1785 | 1994 | 1877 |

| Europe | 138 | Russia * = Turkey | 1222 | 2018 | 1949 |

| Oceania | 4 | Australia | 1873 | 1970 | 1950 |

| S + C America +, Caribbean | 82 | Brazil | 1676 | 2010 | 1960 |

| Africa | 64 | Nigeria | 1902 | 2022 | 1976 |

| Asia | 186 | Indonesia | 1851 | 2018 | 1978 |

| Past | Present | Future |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Issues | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| For a given forest education institution:

|

| For a given forest education institution:

|

| For a given forest education institution:

|

| For a given forest education institution:

|

| For a given forest education institution:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barker, M. Forest Education: Past, Present, and Future. Forests 2025, 16, 1801. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121801

Barker M. Forest Education: Past, Present, and Future. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1801. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121801

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarker, Martin. 2025. "Forest Education: Past, Present, and Future" Forests 16, no. 12: 1801. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121801

APA StyleBarker, M. (2025). Forest Education: Past, Present, and Future. Forests, 16(12), 1801. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121801