Identification of Hiking Target Groups Based on Physical Fitness Levels in Forest Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Methodologies for Measuring Physical Fitness in Natural Environments

2.2. Analysis of Tourism Target Groups

2.3. Target Group in Geotourism

- Age and health status—These directly impact endurance and the capacity to engage in physically demanding activities. Older visitors or those with health limitations may find it difficult to complete more challenging routes [62].

- Level of regular physical activity—Tourists accustomed to regular exercise generally possess greater stamina and are more capable of undertaking demanding hikes or excursions [63].

- Terrain and environmental conditions—Geotourism trails range from gentle walks to strenuous climbs. Weather conditions, such as rainfall or high temperatures, can further affect tourists’ ability to complete a route [64].

- Motivation and purpose of visit—Some tourists are driven by an interest in nature, while others are motivated by geological phenomena. The underlying motivation often determines the type and intensity of physical activity they are willing to undertake [65].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Somatometric Measurements

3.1.1. Motor Skills Testing of Physical Fitness

- T1: Standing long jump.

- T2: Sit-up test.

- T3.a: 12 min run (endurance assessment for individuals aged 10–20 years).

- T3.b: 2 km walk (endurance assessment for individuals over 20 years of age).

3.1.2. Ruffier Functional Test

- They are standardized and scientifically verified.

- They provide a comprehensive picture of fitness by measuring several motor abilities rather than focusing on a single area.

- They are simple to implement and do not require complex equipment.

- They allow comparison with established norms, as results are comparable by age and gender.

- They are applicable across different age categories.

- They support prevention and early intervention, as identifying deficiencies in physical fitness can lead to recommendations for appropriate physical activity or training.

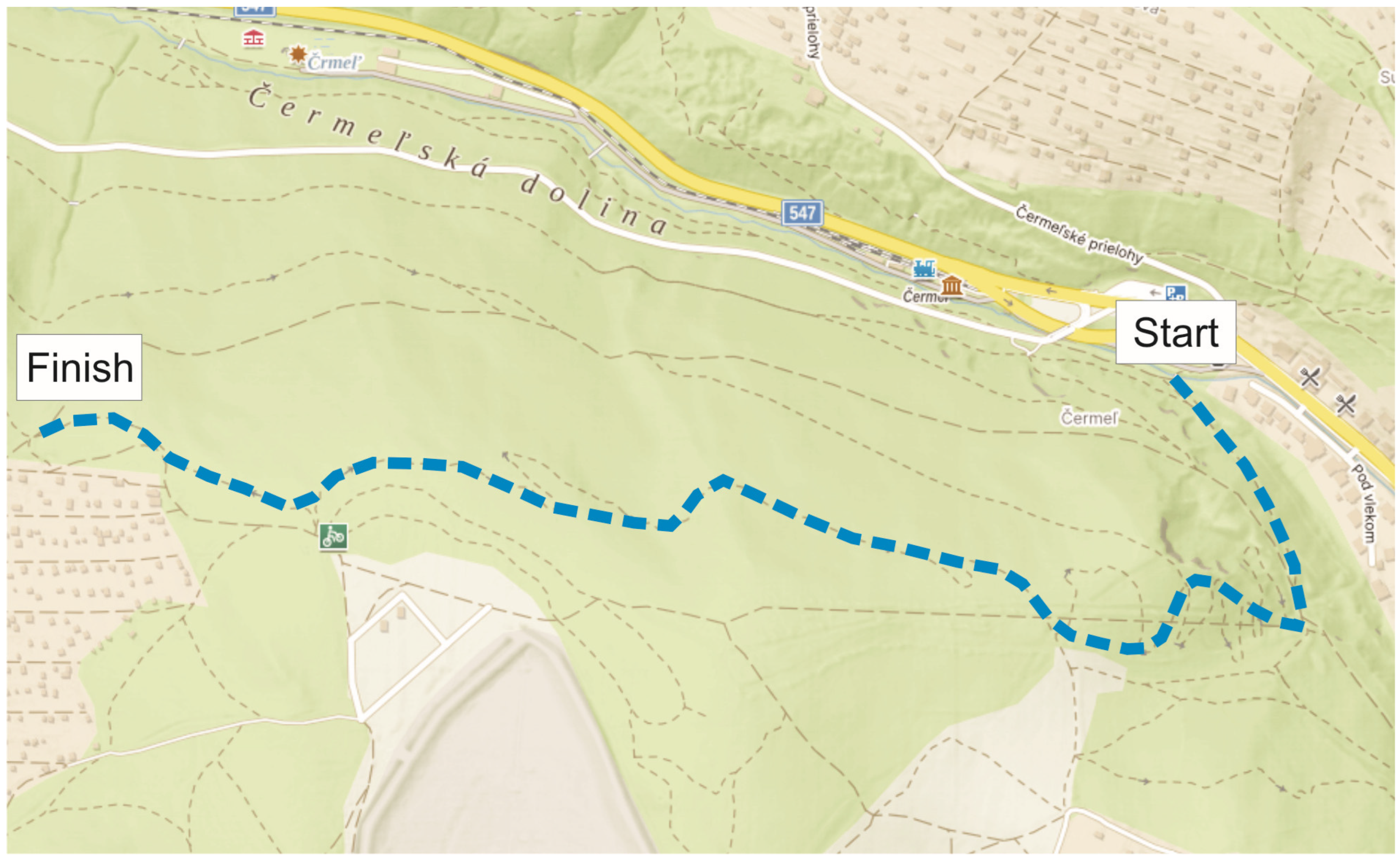

3.1.3. Field Walking

- Technical heritage site: Bankov Mine, historically used for magnesite extraction.

- Natural heritage sites: Studnička Spring and St. John of Nepomuk Spring.

3.2. Characteristics of the Research Sample

- -

- Group 1 (G1): 10–14 years (22 males, 18 females); mean age 12.04 years, mean height 155.63 cm, mean body weight 44.27 kg, mean BMI 18.10.

- -

- Group 2 (G2): 15–20 years (19 males, 21 females); mean age 16.9 years, mean height 173.55 cm, mean body weight 65.03 kg, mean BMI 21.08.

- -

- Group 3 (G3): 21–30 years (21 males, 19 females); mean age 25.18 years, mean height 175.6 cm, mean body weight 71.1 kg, mean BMI 22.91.

- -

- Group 4 (G4): 31–40 years (20 males, 20 females); mean age 35.28 years, mean height 172.72 cm, mean body weight 69.36 kg, mean BMI 23.11.

- -

- Group 5 (G5): 41–50 years (19 males, 21 females); mean age 45.0 years, mean height 172.45 cm, mean body weight 73.43 kg, mean BMI 24.65.

- -

- Group 6 (G6): 51 years and older (21 males, 19 females); mean age 54.55 years, mean height 171.62 cm, mean body weight 71.56 kg, mean BMI 24.24.

Research Sample Selection

- -

- Age range: between 18 and 60 years, representing the active working-age population, which also constitutes the demographic most frequently engaged in hiking and geotourism activities.

- -

- Adequate physical fitness: participants were in good general health, without serious musculoskeletal or chronic conditions that could influence performance on physical fitness tests or pose safety risks during field activities.

- -

- Voluntary participation: participants expressed willingness to complete the entire research process, including both laboratory and field-testing components.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

- Body mass index (BMI);

- Motor abilities;

- Physical fitness.

4. Results

4.1. Somatometric Measurements and BMI

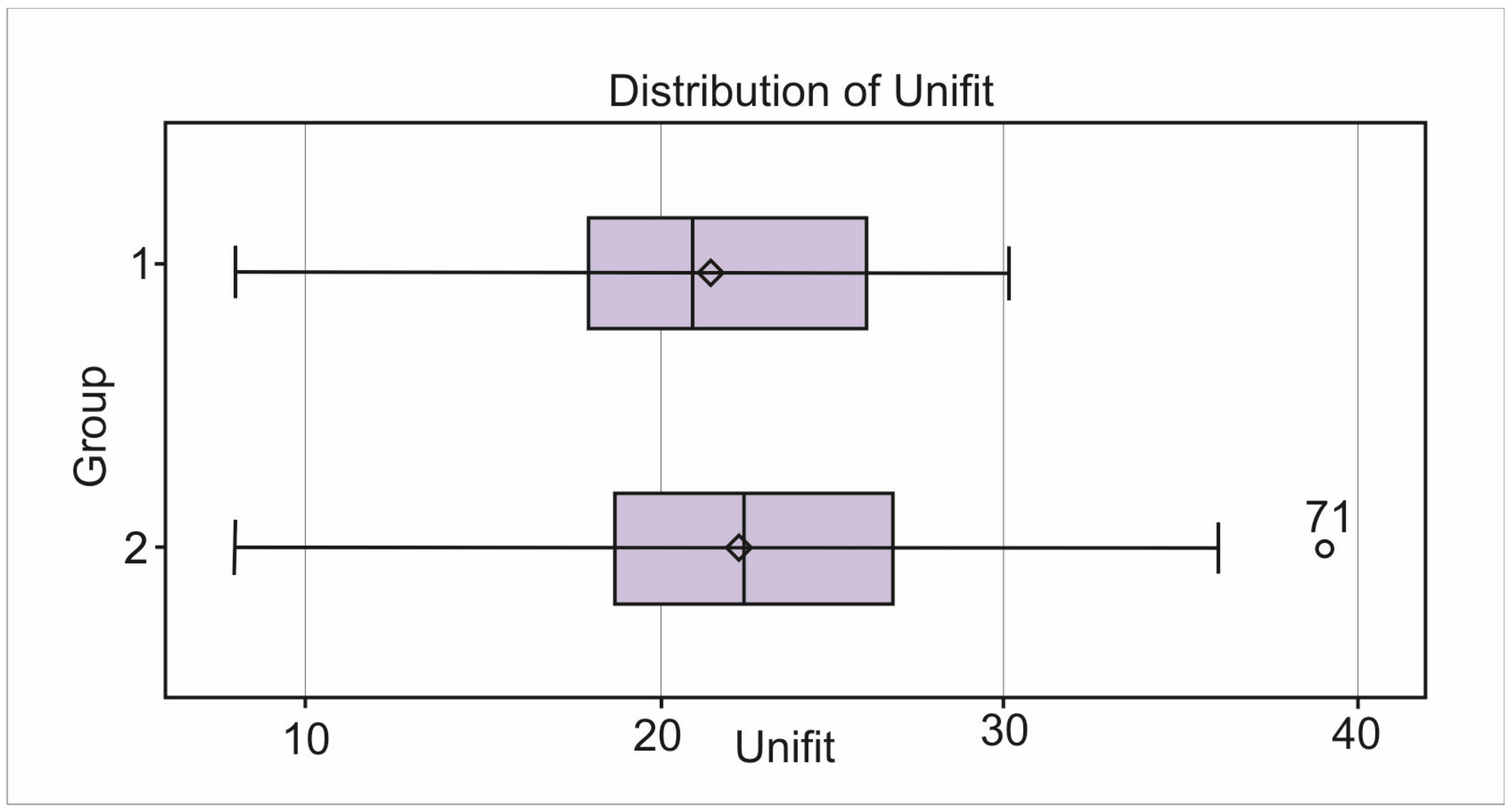

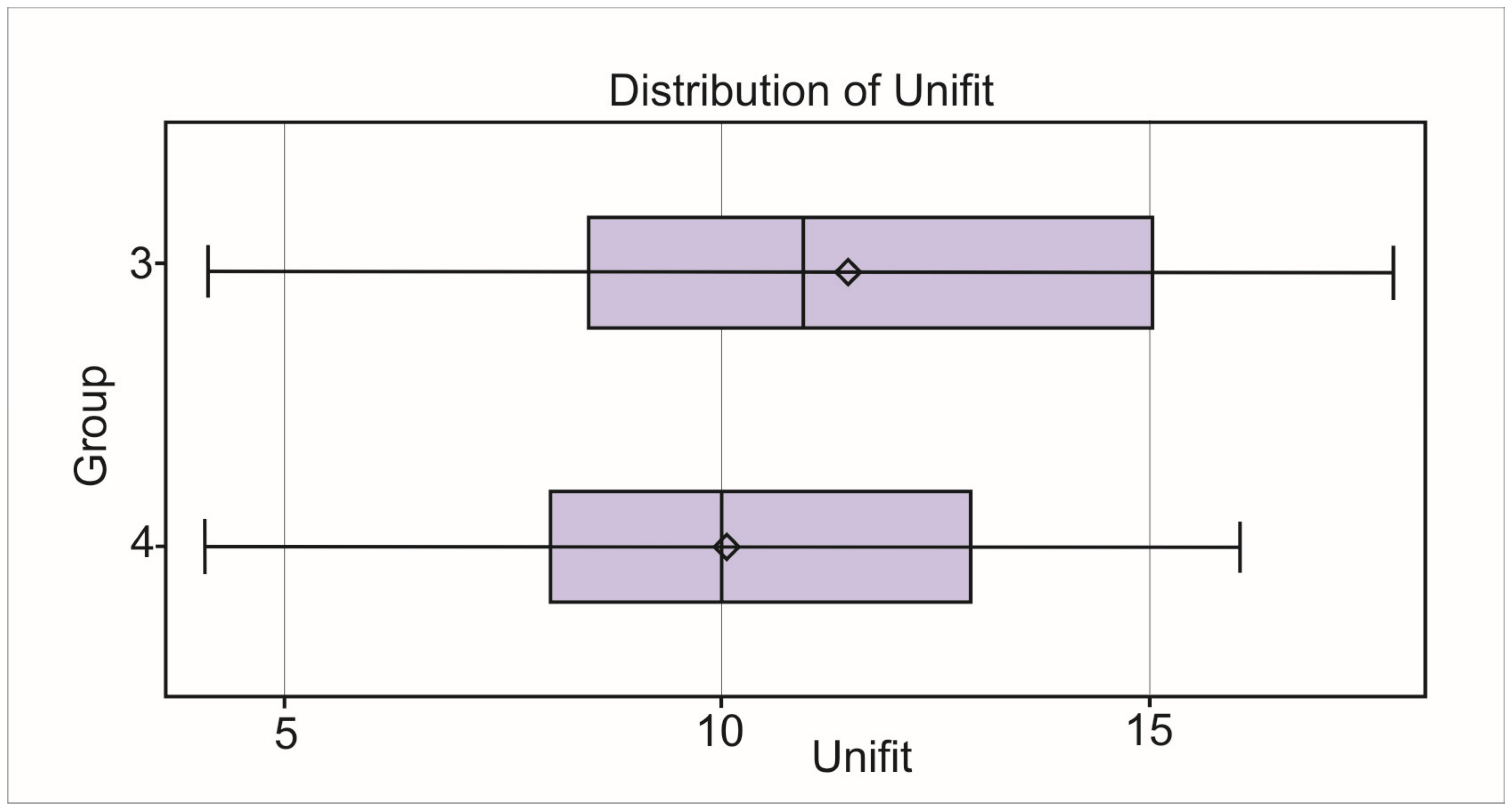

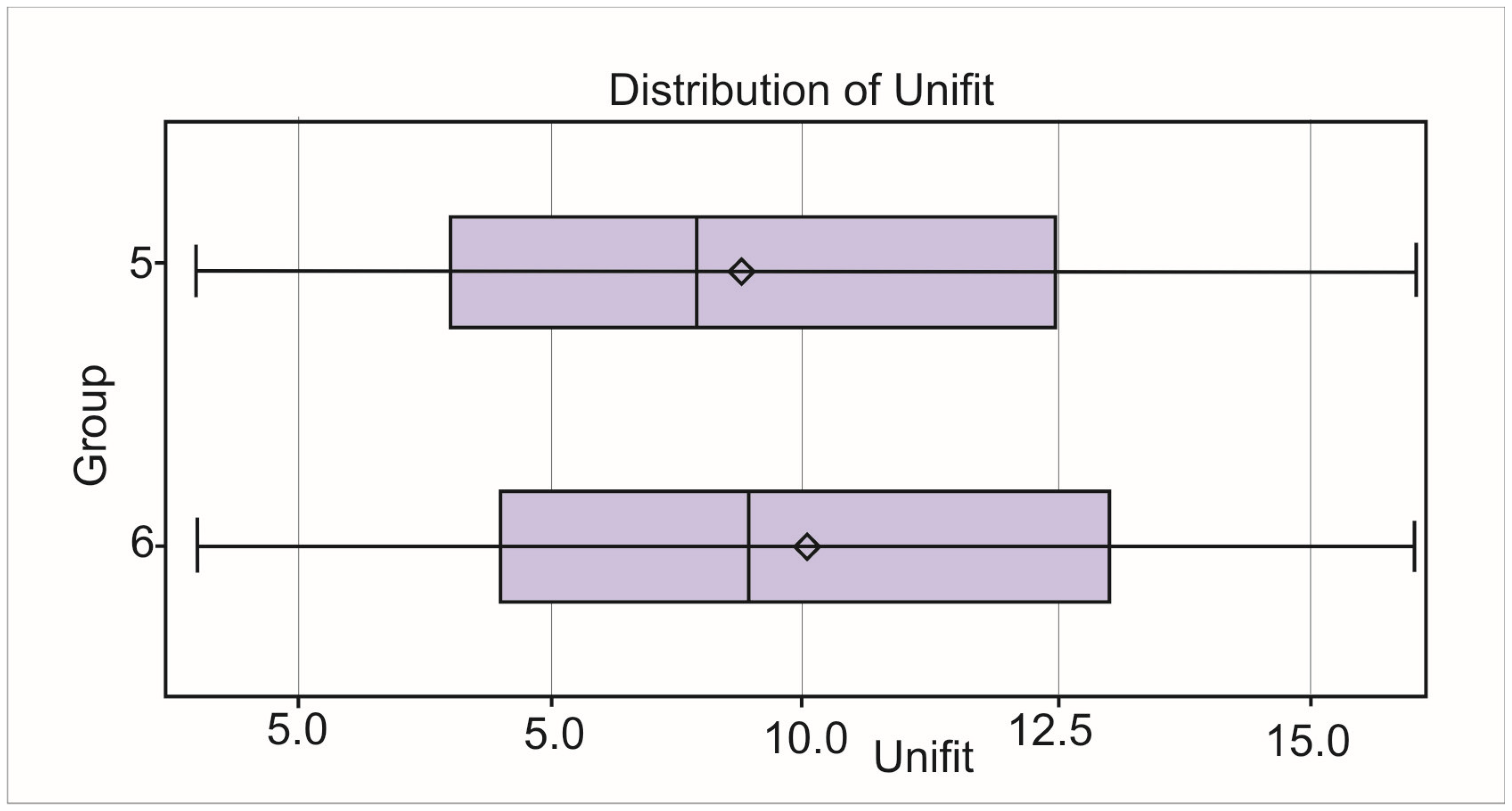

4.2. Motor Ability Testing—UNIFIT Test

- Group 1 (10–14 years) ↔ Group 2 (15–20 years);

- Group 3 (21–30 years) ↔ Group 4 (31–40 years);

- Group 5 (41–50 years) ↔ Group 6 (51–60 years).

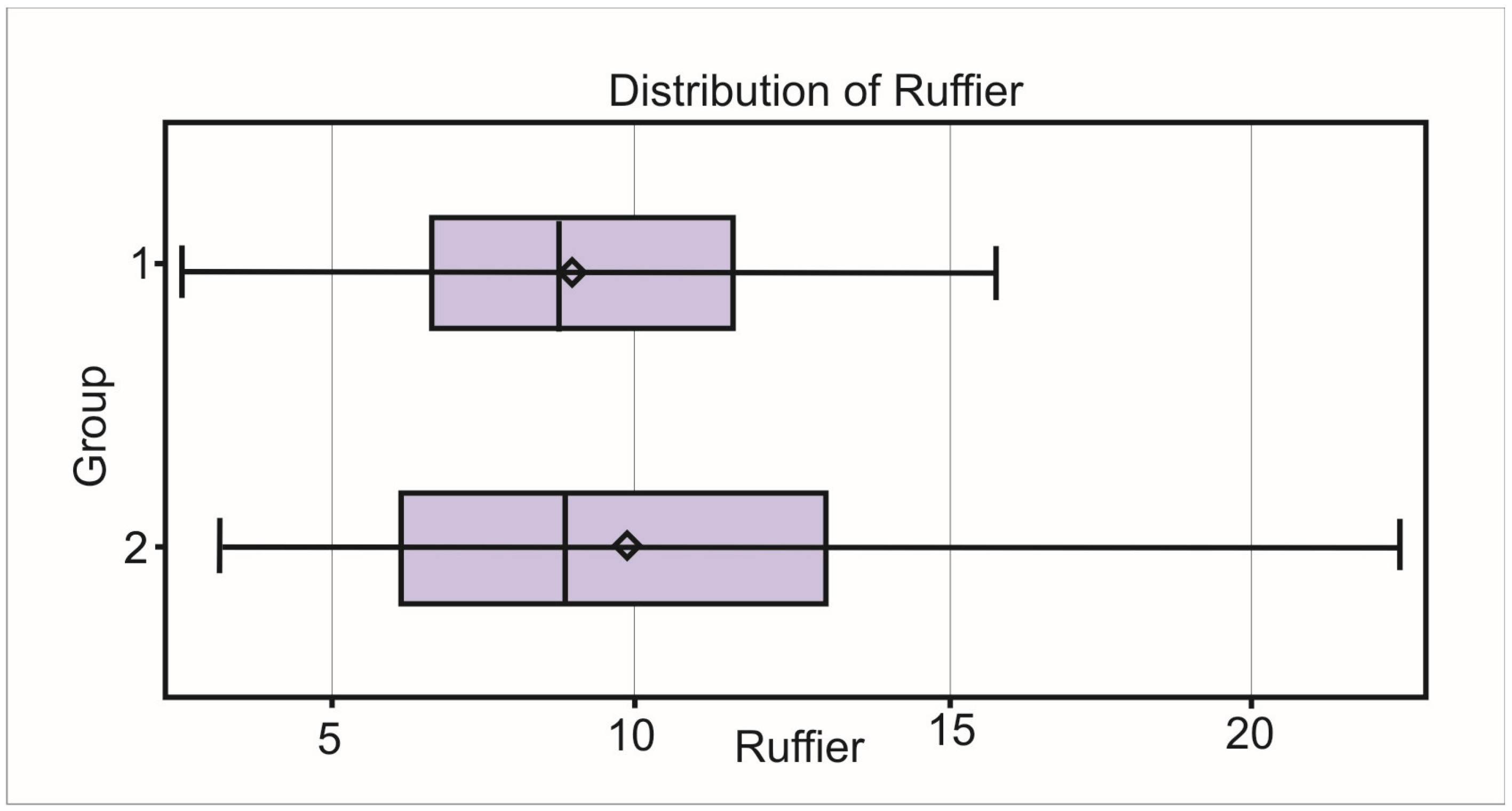

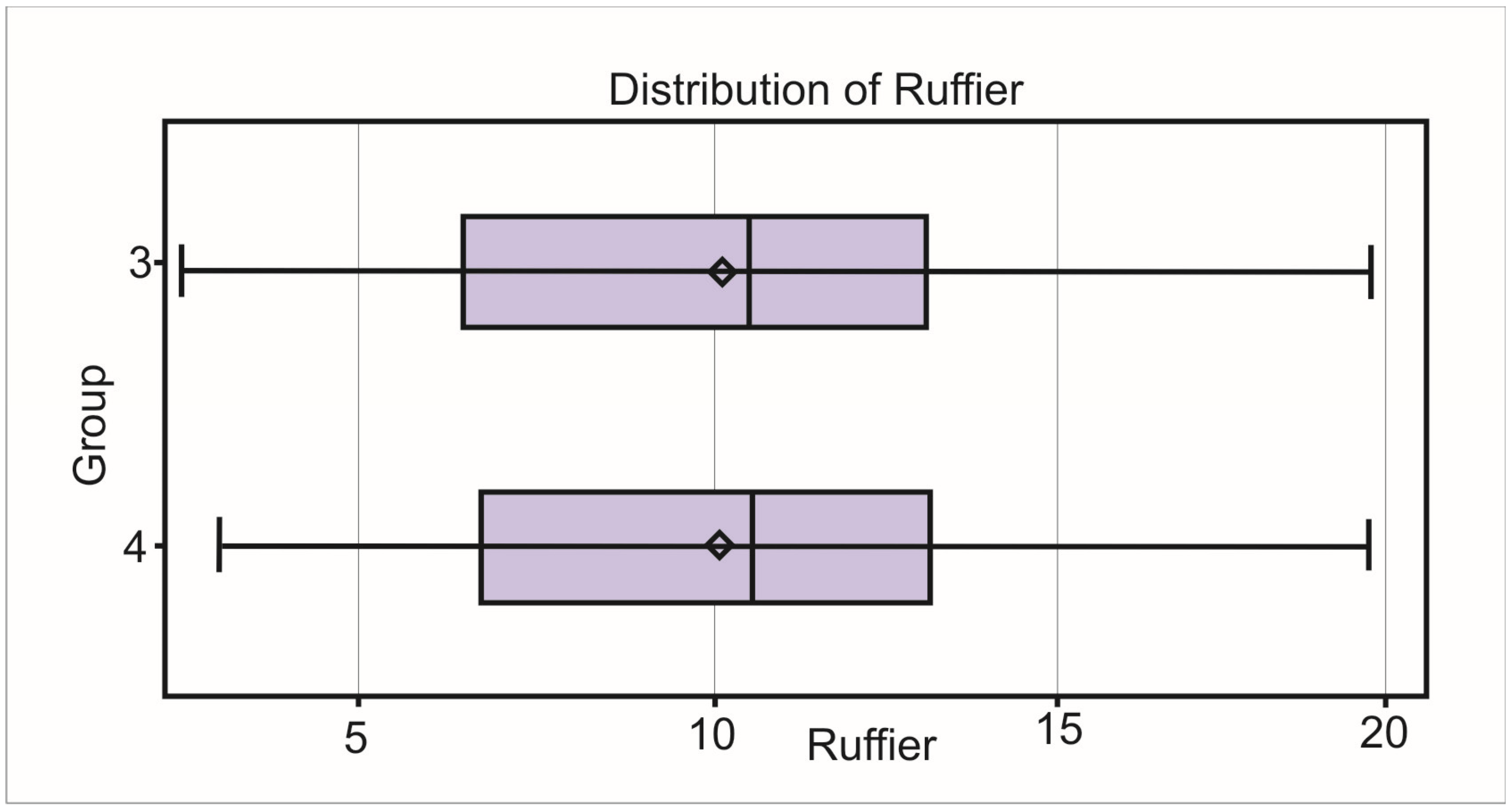

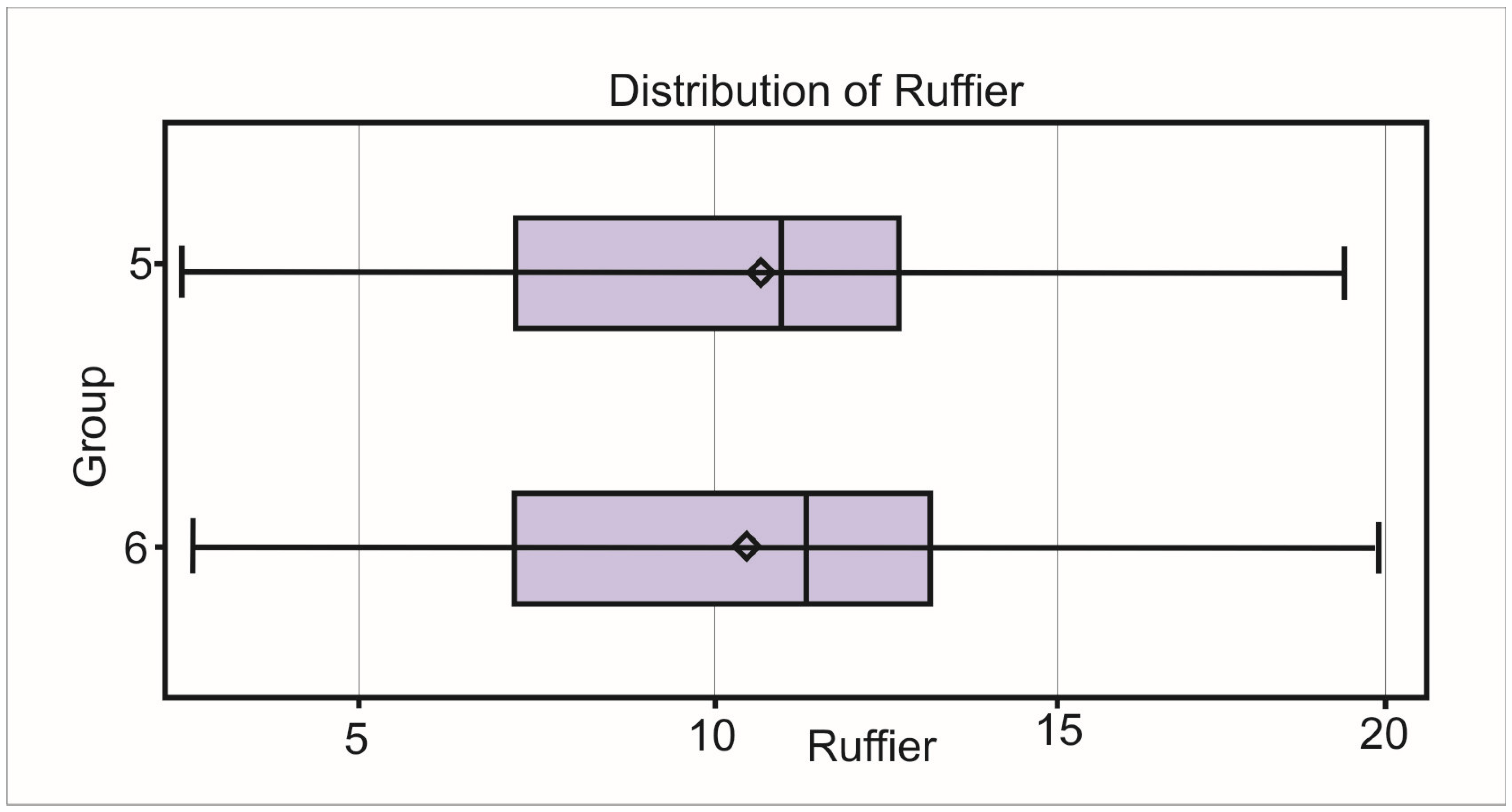

4.3. Physical Fitness Testing—Ruffier Functional Test

- G1—good physical fitness.

- G2—average physical fitness.

- G3—poor physical fitness.

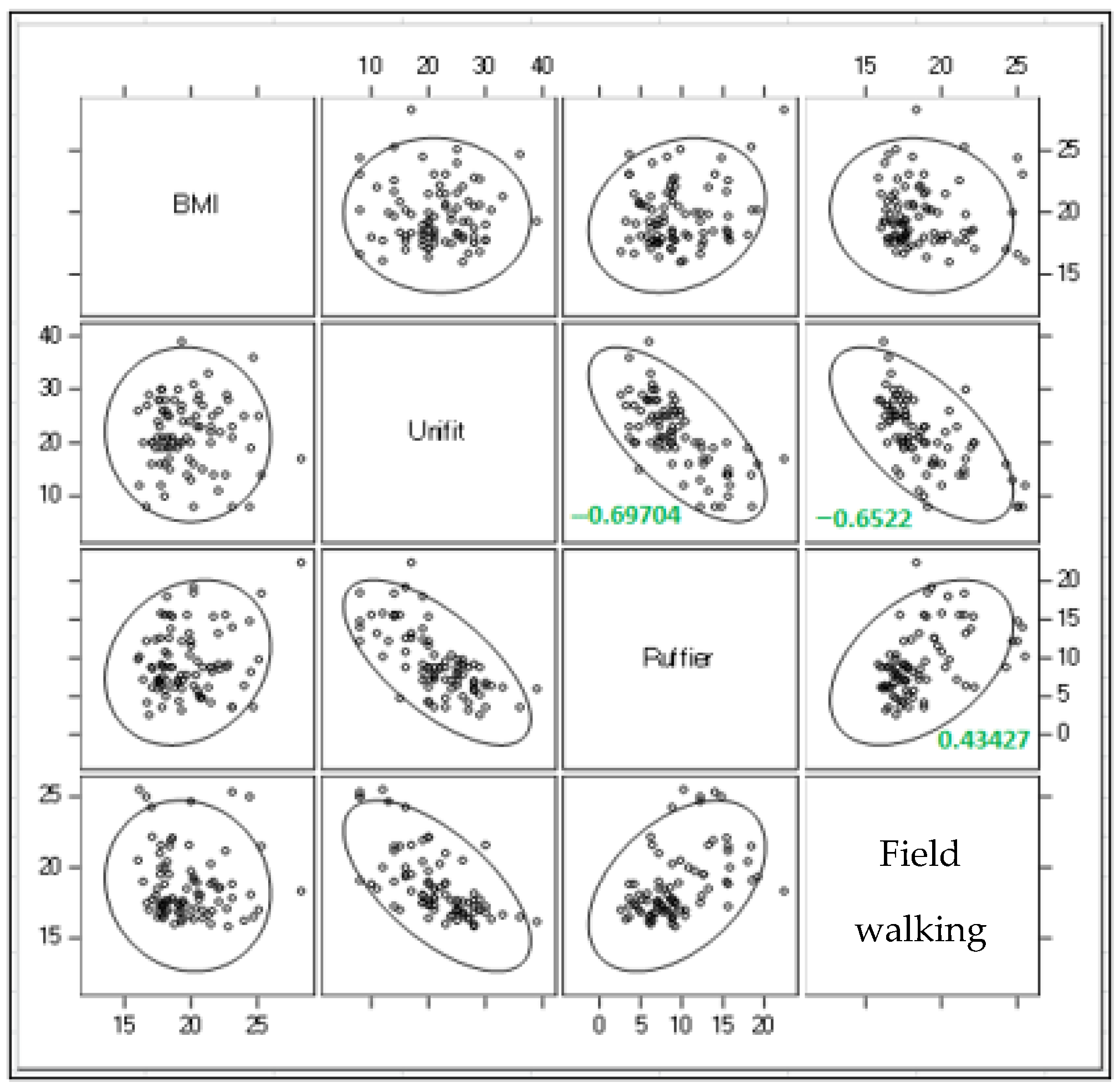

Verification of the Proposed Geotourist Categorization

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Market Data Forecast. Available online: https://www.marketdataforecast.com/market-reports/geotourism-market (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Boley, B.B.; Nickerson, N.P.; Bosak, K. Measuring geotourism: Developing and testing the geotraveler tendency scale (GTS). J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlíková, H. Nové Trendy v Nabídce Cestovního Ruchu, 1st ed.; Grada: Praha, Czech Republic, 2013; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Matlovičová, K.; Klamár, R.; Mika, M. Turistika a Jej Formy; Grafotlač Prešov, Prešovská Univerzita: Prešov, Slovakia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, R.K. Global Geotourism—An Emerging Form of Sustainable. Tour. Czech J. Tour. 2013, 2, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerekeš, J. Vidiecky Turizmus a Agroturizmus v Regiónoch Turizmu; 1000 kníh: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2019; p. 243. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, H. Leisure and later life: Past, present and future. Leis. Stud. 2004, 23, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šambronská, K.; Matušíková, D.; Šenková, A.; Kormaníková, E. Geoturism and its sustainable products in destination management. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2023, 46, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussard, J.; Reynard, E. Geotourism and interpretation of geomorphology in mountain tourism: The case of UNESCO Swiss Alps Jungfrau-Aletsch. J. Alp. Res. 2022, 110, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Tverijonaite, E. Geotourism: A systematic literature review. Geosciences 2018, 8, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubalíková, L. Assessing geotourism resources in forested landscapes: A case study from the Czech Republic. Resources 2019, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.; Oliveira, R.; Brilha, J. Geodiversity and forest ecosystems: Interactions for sustainable geotourism. Environ. Earth Sci. 2022, 81, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. Forest bathing: Nature therapy for health and well-being. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2022, 27, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, P.; Wang, S.; Li, W. Forest-based tourism and visitor well-being: Integrating ecosystem services and experiential benefits. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3479. [Google Scholar]

- Bamwesigye, D.; Fialova, J.; Kupec, P.; Yeboah, E.; Łukaszkiewicz, J.; Fortuna-Antoszkiewicz, B.; Botwina, J. Urban Forest Recreation and Its Possible Role throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic. Forests 2023, 14, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poehler, P.; Bachinger, M. Recreation in Forests: Implications from the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Sustainable Tourism: Frameworks, Practices, and Innovative Solutions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Farkic, J.; Isailovic, G.; Taylor, S. Forest bathing as a mindful tourism practice. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2021, 2, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Notaro, S.; Sergiacomi, C.; Di Mascio, F. The Economic Value of Forest Bathing: An Example Case of the Italian Alps. Forests 2024, 15, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, J.; Peng, L.; Zhang, Y. Forest Ecosystem Conservation Through Rural Tourism and Ecosystem Services: A Systematic Review. Forests 2025, 16, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Lin, L.; Xiaotong, Z. Influence of El Niño events on sea surface salinity over the central equatorial Indian Ocean. Environ. Res. 2020, 182, 109097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, K.; Lukács, A. Motivation and mental well-being of long-distance hikers: A quantitative and qualitative approach. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Page, S.J. The Geography of Tourism and Recreation: Environment, Place and Space, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.; Fletcher, J.; Fyall, A.; Gilbert, D.; Wanhill, S. Tourism: Principles and Practice, 4th ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S.-L.; Hsu, M.-C. Motivation-Based Segmentation of Hiking Tourists in Taiwan. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 5, 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Víquez-Paniagua, A.G.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Pérez-Orozco, A. The role of motivationsin the segmentation of ecotourism destinations: A study from Costa Rica. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, T.W.; Cho, C.H.; Swartz, A.M.; Cho, Y.; Strath, S.J. Validation of walking and stepping tests to predict maximal oxygen uptake. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, I.M.; Marques, G.; Garcia, N. Development of technologies for monitoring the six-minute walk test: A systematic review. Sensors 2022, 22, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautmans, I.; Lambert, M.; Mets, T.; De Bruin, E.D. The six-minute walk test in community dwelling elderly: Influence of motivation and learning effect. J. Rehabil. Med. 2004, 36, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Umiastowska, D.; Kupczyk, T. Application of the Ruffier test in field assessment of physical fitness among physically active adults. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2021, 21, 314–321. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.; Mańka, A.; Król, H. The Ruffier test as an indicator of cardiovascular efficiency in youth physical education. Polish J. Sport Tour. 2019, 26, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Drid, P.; Figlioli, F.; Tabben, M.; Krstulović, S.; Erčulj, F. Relationship between the Ruffier test and aerobic fitness indicators in athletes: A field-based validation study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8709. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, A.; Gaspar de Matos, M.; Carreiro da Costa, F. Physical fitness and health indicators in adolescents: Field-based testing validity. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 525–531. [Google Scholar]

- Weiglein, L.; Herrick, J.; Kirk, S.; Kirk, E. The 1-mile walk test is a valid predictor of VO2max and is reliable in healthy adults. Mil. Med. 2011, 176, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, J.F.; Bull, F.; Guthold, R.; Heath, G.W.; Kelly, P. Progress in physical activity research and surveillance: Implications for fitness testing in schools and communities. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e1263–e1274. [Google Scholar]

- Kudlacek, M.; Frömel, K.; Svozil, Z. Monitoring physical fitness in adolescents: The UNIFIT test battery. Acta Gymnica 2016, 46, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, E.; Vincze, F.; Csányi, T. Validity and reliability of UNIFIT test battery in assessing youth physical fitness. J. Hum. Kinet. 2022, 82, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lunt, H.; Roake, J.; Sainsbury, R. Validation of the one-mile walk test for VO2max prediction in a military cohort. Mil. Med. 2013, 178, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekritthikrai, N.; Phattharasupakun, N.; Intharawichian, N. Concurrent validity of a new mobile application for the six-minute walk test. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čuka, P. Základy Teórie, Metodológie a Regionalizácie Cestovného Ruchu, 1st ed.; Vydavateľstvo Prešovskej Univerzity v Prešove: Prešov, Slovakia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241599979 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Palátková, M. Marketing Destinace Cestovního Ruchu; Grada Publishing: Praha, Czech Republic, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Horner, S.; Swarbrooke, J. Consumer Behaviour in Tourism, 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, A.V.; Bennett, M.M. The Marketing of Tourism Products: Concepts, Issues and Cases, 1st ed.; International Thomson Business Press: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, A.V.; Bennett, M.M. The Marketing of Tourism Products: Concepts, Issues and Cases, 3rd ed.; Thomson Learning: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stynes, D.J. Marketing Tourism. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 1983, 54, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. A phenomenology of tourist experiences. Sociology 1979, 13, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L. Culinary Tourism; University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, KY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, A.M.; Bello, L. The construct „lifestyle” in market segmentation: The behavior of tourist consumers. Eur. J. Mark. 2002, 36, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryglová, K. Cestovní Ruch. Soubor Studijních Materiálů, 3rd ed.; Key Publishing: Ostrava, Czech Republic, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kiráľová, A. Marketing Destinace Cestovního Ruchu, 1st ed.; Ekopress: Praha, Cyech Republic, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Frain, J. Introduction to Marketing, 4th ed.; EMEA: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Goeldner, C.H.; Brent, R. Tourism: Principles, Practices, Philosophies, 11th ed.; Wiley: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T.A. Towards a history of geotourism: Definitions, antecedents and the future. In The History of Geoconservation; Burek, C.V., Prosser, C., Eds.; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2008; pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, C. Towards a typology of visitors to geosites. In Proceedings of the Second Global Geotourism Conference, Making Unique Landforms Understandable, Mulu, Sarawak, Malaysia, 17–20 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Molokáč, M.; Alexandrová, G.; Kobylanska, M.; Hlavňová, B.; Hronček, P.; Tometzová, D. Virtual Mine-educational model for Wider Society. In Proceedings of the ICETA 2017, 15th International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications, Stará Lesná, Slovakia, 21–22 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tavallaee, S.; Asadi, A.; Abya, H.; Ebrahimi, M. Tourism planning: An integrated and sustainable development approach. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2014, 4, 2495–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsani, N.T. Sustainable Tourism in Geoparks through Geotourism and Networking. Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. 2012. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/15570619.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Frey, M.L. Geotourism—Examining Tools for Sustainable Development. Geosciences 2021, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrba, Ľ.; Kolačkovská, J.; Kudelas, D.; Kršák, B.; Sidor, C. Geoheritage and Geotourism Contribution to Tourism Development in Protected Areas of Slovakia—Theoretical Considerations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, I.; Hagenloh, G.; Croft, D. Visitor monitoring along roads and hiking trails: How to determine usage levels in tourist sites. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitten, D.; Overholt, J.R.; Haynes, F.I.; D’Amore, C.C.; Ady, J.C. Hiking: A Low-Cost, Accessible Intervention to Promote Health Benefits. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2016, 12, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, C.; Blair, S.N.; Haskell, W.L. Physical Activity and Health: An Evidence-Based Approach to Practice, 2nd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Frömel, K.; Kudláček, M.; Groffik, D. Tourism and Physical Activity Preferences: Development and Sustainability Strategy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbos, R.; Altschuler, B.; Brownlee, M. Weather Studies in Outdoor Recreation and Nature-Based Tourism: A Research Synthesis and Gap Analysis. Leis. Sci. 2017, 40, 533–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, M. Toward a Better Understanding of Motivations for a Geotourism Experience: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mandzáková, M. Úvod do Športovej Antropológie, 1st ed.; Belianum, Vydavateľstvo Univerzity Mateja Bela: Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kouchi, M.; Hanihara, K. An analysis of errors in somatometric research. J. Anthropol. Soc. Nippon 1981, 89, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stříbrná, L.; Kopecký, M.; Matějovičová, B.; Charamza, J. Body mass index a image těla u českých a slovenských studentek na vysoké škole. Slov. Antropológia 2017, 20, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Měkota, K. Unifit Test (6-60); Univerzita Palackého: Olomouc, Czech Republic, 1995; p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- Ruffierova Funkčná Skúška. Available online: https://trenujeme.sk/ruffierova-funkcna-skuska?srsltid=AfmBOopIlb4unFrgR4EOa33GIhvzjoyBfscbWUv7i4O3Ai9LlCwa0wxU (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Molokáč, M.; Kršák, B.; Sidor, C. Models for mapping tourists (regarding surrounding). e-Rev. Tour. Res. 2016, 13, 550–560. [Google Scholar]

- Országhová, D. Študijné výsledky z matematiky a ich analýza pomocou t-testu Study outcomes of mathematics and their analysis using t-test. Forum Stat. Slovacum 2012, 3, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.K. T test as a parametric statistic. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2015, 68, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlavoňová, D.; Hedvábný, P.; Kalina, T. Vliv věku, pohybové aktivity a dosaženého vzdělání na vybrané ukazatele obezity u dospělé populace ČR. In Vybrané Aspekty Zdatnosti Dospělé Populace České Republiky; Cacek, J., Grasgruber, P., Hlavoňová, D., Eds.; Masarykova Univerzita: Brno, Czech Republic, 2014; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sigmund, M.; Dostálová, I.; Sigmundová, D. Celkové a segmentální zastoupení tělesného tuku u žen pohybově aktivních a inaktivních ve věku adultus. Česká Antropol. 2013, 60, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nekouie Sadry, B. The future of geotourism. In The Geotourism Industry in the 21st Century, 1st ed.; Apple Academic Press: Waretown, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, G. Geological heritage and geo-tourism. In Geological Heritage: Its Conservation and Management; Barettino, D., Wimbledon, W.A.P., Gallego, E., Eds.; Instituto Tecnologico Geominero de Espana: Madrid, Spain, 2000; pp. 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Pralong, J.P. Geotourism: A new Form of Tourism utilising natural Landscapes and based on Imagination and Emotion. Tour. Rev. 2006, 61, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, K.; Sers, S.; Buday, L.; Wäsche, H. Why hikers hike: An analysis of motives for hiking. J. Sport Tour. 2023, 27, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykletun, R.J.; Oma, P.; Aas, P. When the hiking gets tough: “New adventurers” and the “extinction of experiences”. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 36, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, P.; Arrowsmith, C.; Jackson, M. Determining hiking experiences in nature-based tourist destinations. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elands, B.H.M.; Lengkeek, J. The tourist experience of out-of-home leisure and travel. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 105, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Scott, D. Measuring environmentally responsible behavior among college students: Validity and reliability. J. Interpret. Res. 2004, 9, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Migoń, P. Geoheritage and geotourism. A European perspective. Geologos 2018, 24, 173–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D.; Moore, S.A.; Dowling, R.K. Natural Area Tourism: Ecology, Impacts and Management, 2nd ed.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reynard, E.; Giusti, C. The Landscape and the Cultural Value of Geoheritage; Reynard, E., Brilha, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchiato, M.; Borasio, N.; Scettri, E.; Franzoi, V.; Duregon, F.; Savino, S.; Ermolao, A.; Neunhaeuserer, D. Are Suggested Hiking Times Accurate? A Validation of Hiking Time Estimations for Preventive Measures in Mountains. Medicina 2025, 61, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pál, M.; Albert, G. Digital cartography for geoheritage: Turning an analogue geotourist map into digital. Proc. ICA 2019, 2, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassoulas, C.; Nikolakakis, E.; Staridas, S. Digital Tools to Serve Geotourism and Sustainable Development at Psiloritis UNESCO Global Geopark in COVID Times and Beyond. Geosciences 2022, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Testing Segment | Test/Activity | Location | Measured Ability/Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somatometric measurements | Height, weight, BMI | Technical University Gymnasium Košice, | Somatic parameters |

| Functional cardio-vascular test | Ruffier test | Technical University Gymnasium Košice, | Cardiovascular response to load (pulse, recovery) |

| Motor skills—UNIFIT | Standing long jump | Technical University Gymnasium Košice, | Explosive strength of the lower limbs |

| Sit-ups (30 s) | Technical University Gymnasium Košice, | Trunk muscle strength | |

| Endurance tests | 2 km walk | Tartan track, Technical University Stadium | Aerobic endurance |

| 12 min run (Cooper test) | Tartan track, Technical University Stadium | Aerobic capacity, endurance | |

| Field test | Walking in a natural environment | Hiking trail Bankov (Košice surroundings) | Practical endurance and adaptation to natural terrain |

| Two-Sample t-Test: Field Walking | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | N | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | Variance | t Value | Pr > |t| |

| G1 (good fitness) | 80 | 18.64 | 15.83 | 25.5 | 5.32 | −5.14 | <0.001 |

| G2 (average fitness) | 80 | 20.53 | 16.5 | 27.5 | 5.5 | ||

| Two-Sample t-Test: Field Walking | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | N | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | Variance | t Value | Pr > |t| |

| G2 (average fitness) | 80 | 20.52 | 16.5 | 27.5 | 5.5 | −4.38 | <0.001 |

| G3 (poor fitness) | 80 | 22.23 | 18.75 | 29.2 | 6.63 | ||

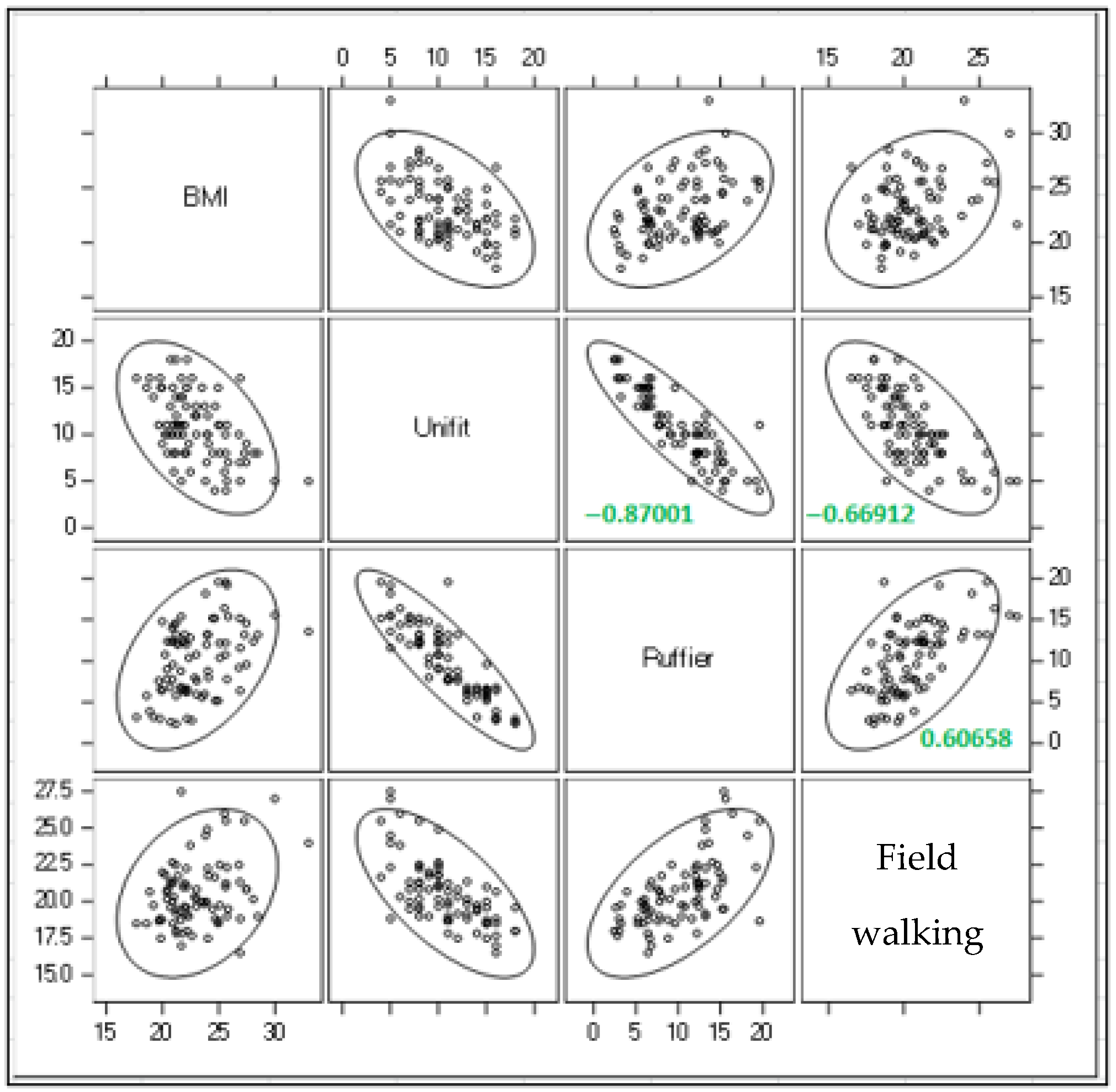

| Pearson Correlation Coefficients, N = 80/S Prob > |r| Under H0: Rho = 0 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Test | Test | |

| Unifit | Ruffier | ||

| G1 (good physical fitness) | Field walking | −0.65 <0.0001 | 0.43 <0.0001 |

| G2 (average physical fitness) | Field walking | −0.66 <0.0001 | 0.60 <0.0001 |

| G3 (poor physical fitness) | Field walking | −0.81 <0.0001 | 0.76 <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hlaváčová, J.; Molokáč, M.; Tometzová, D. Identification of Hiking Target Groups Based on Physical Fitness Levels in Forest Environment. Forests 2025, 16, 1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111728

Hlaváčová J, Molokáč M, Tometzová D. Identification of Hiking Target Groups Based on Physical Fitness Levels in Forest Environment. Forests. 2025; 16(11):1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111728

Chicago/Turabian StyleHlaváčová, Jana, Mário Molokáč, and Dana Tometzová. 2025. "Identification of Hiking Target Groups Based on Physical Fitness Levels in Forest Environment" Forests 16, no. 11: 1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111728

APA StyleHlaváčová, J., Molokáč, M., & Tometzová, D. (2025). Identification of Hiking Target Groups Based on Physical Fitness Levels in Forest Environment. Forests, 16(11), 1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111728