Detection of Vegetation Proximity to Power Lines: Critical Review and Research Roadmap

Abstract

1. Introduction

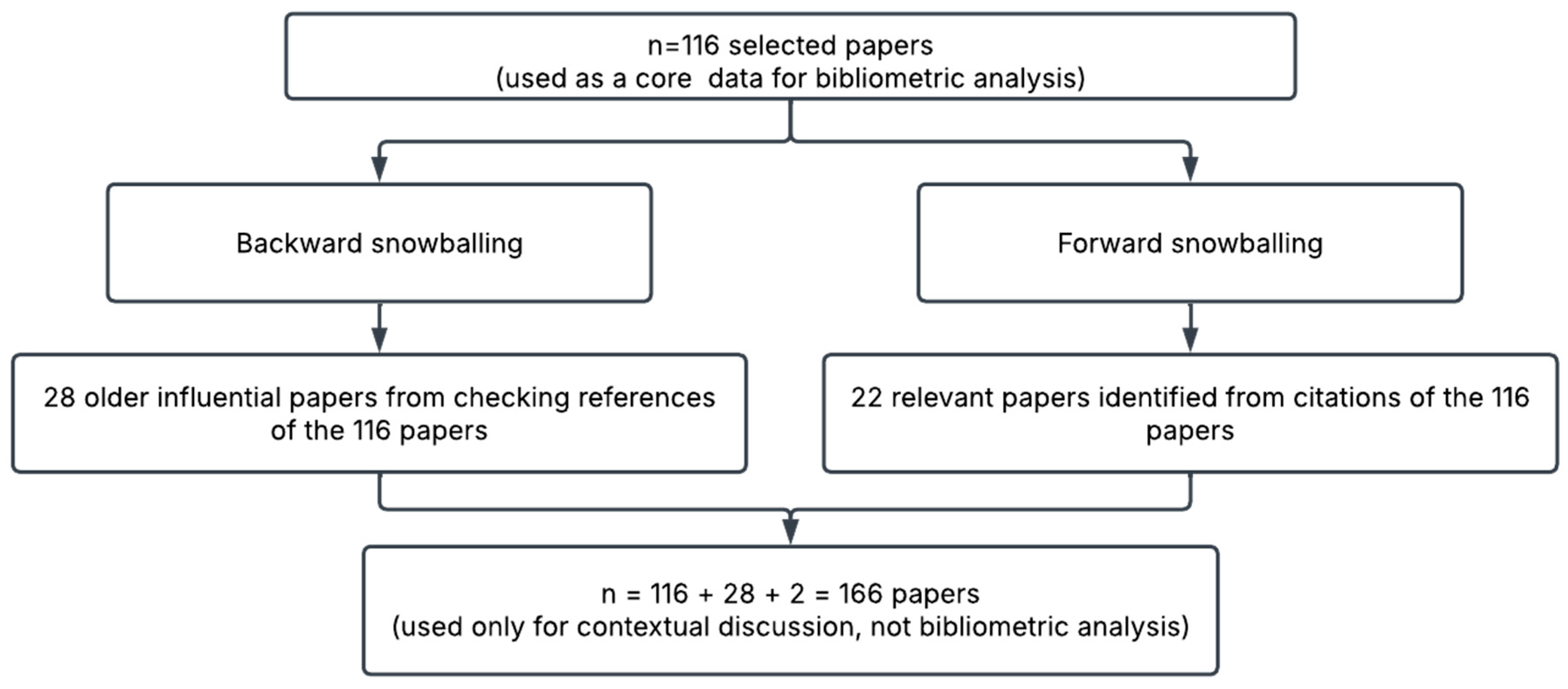

2. Review Method

2.1. Paper Selection Method

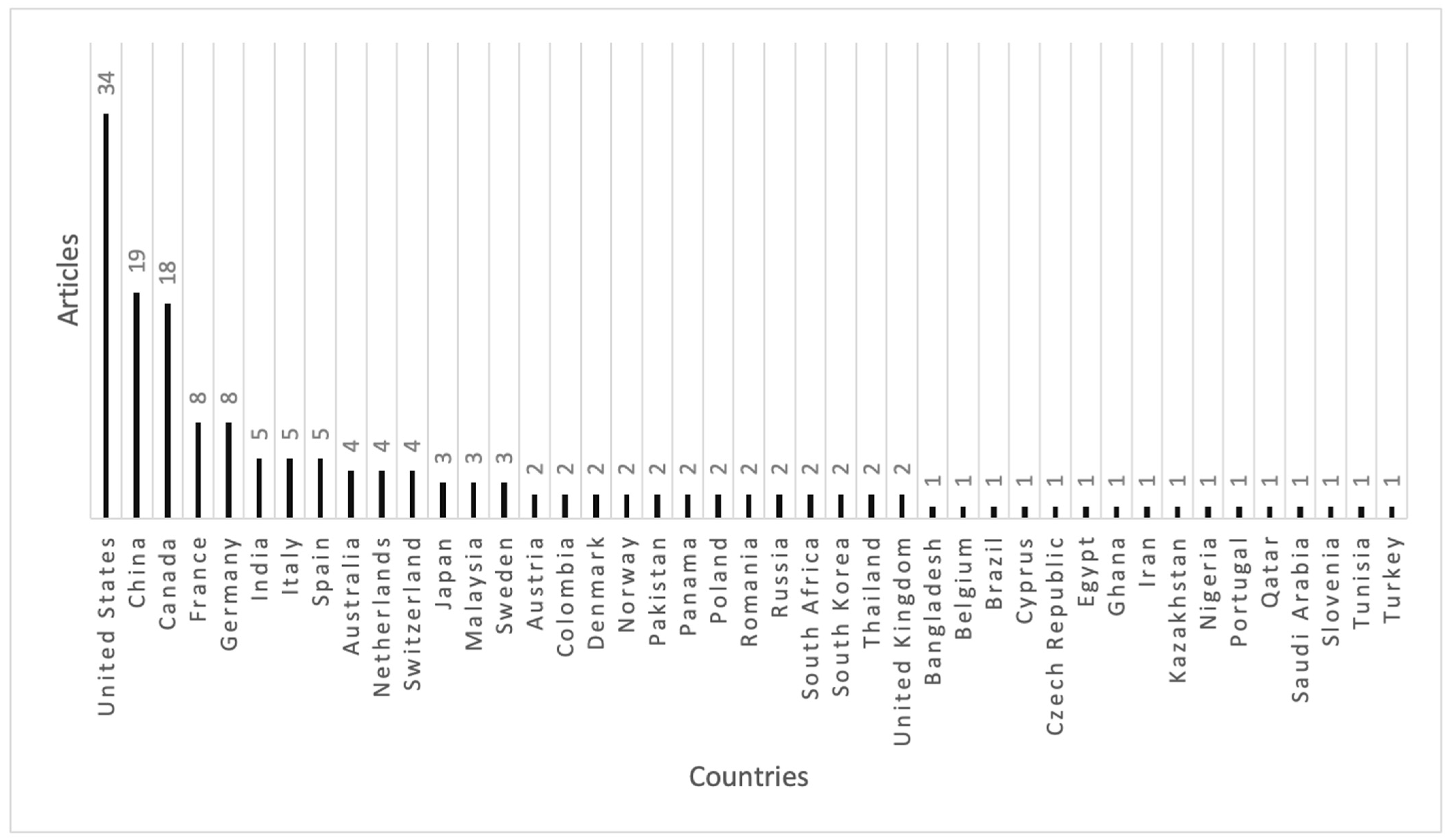

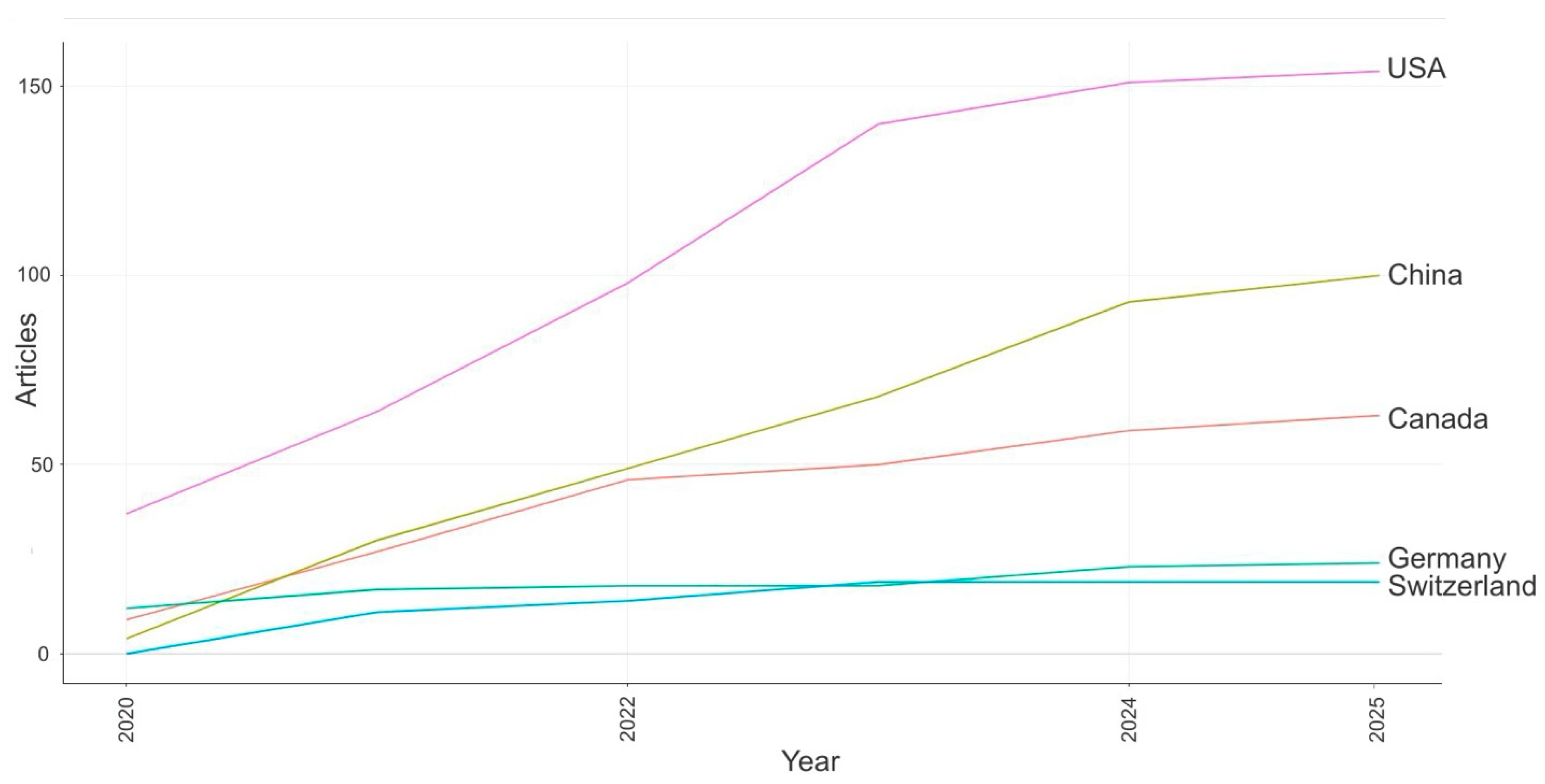

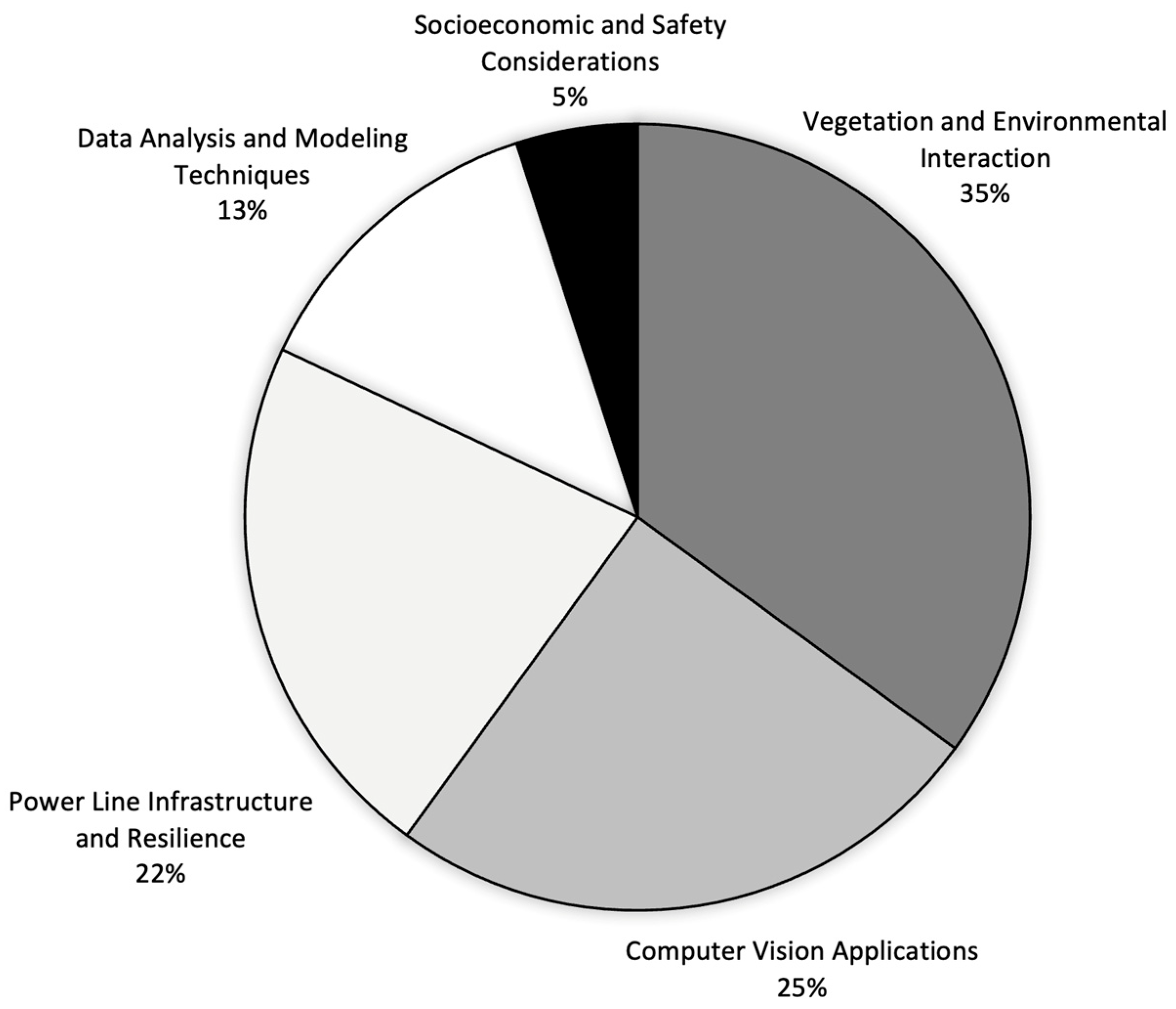

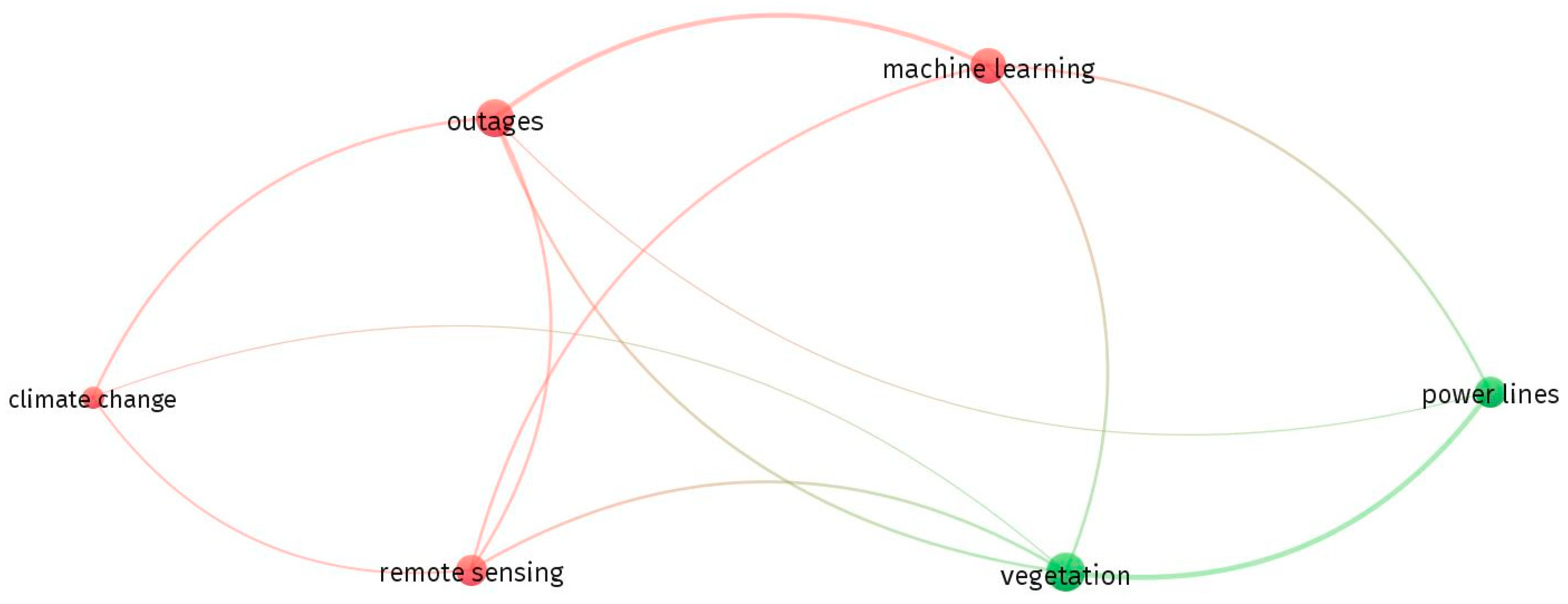

2.2. Paper Distribution and Bibliometric Analysis

3. Outages Caused by Weather Events

3.1. Overview

3.2. Wind-Related Outages

3.3. Rain, Snow and Freezing Rain Outages

3.4. Lightning

4. Proximity Detection

4.1. Object Detection

4.1.1. Conventional ML Approaches

4.1.2. Deep Learning Approaches

4.1.3. Image-Based vs. Point Cloud Methods

4.1.4. Transmission Network vs. Distribution Network

4.2. Post-Processing Techniques for Proximity Detection

| Reference | Year | Objective | Investigated Network/Technique | Data Source | Main Focus | ML/DL | Power Line Detection | Vegetation Detection | Vegetation Proximity Detection to Power Lines |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni et al. [83] | 2025 | Detect and predict tree-related risks and vegetation encroachment on transmission lines | Random Forest, 3D catenary reconstruction, distance-based risk detection | UAV LiDAR (DJI Matrice 350 + Zenmuse L1) | Dynamic risk detection and five-year prediction of vegetation proximity in a 110 kV corridor | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Harini et al. [84] | 2025 | Monitor vegetation encroachment and fire risk around power lines | YOLOv5, LiDAR-derived CHM, distance- and height-based risk assessment | Satellite and aerial images, LiDAR point clouds | Power line and vegetation detection with proximity risk and wildfire-mitigation context | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Al-Najjar et al. [85] | 2025 | Automated detection and reporting of vegetation encroachment on power lines | DBSCAN clustering, PCA alignment and rotation, sliding window traversal, voxel downsampling, proximity-based severity classification | Airborne and mobile LiDAR point clouds from ECLAIR, DALES, and Toronto 3D | Generalized LiDAR pipeline with scalable proximity analysis and severity reporting across diverse datasets | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Rong et al. [86] | 2025 | Real-time detection of power lines and quantitative assessment of vegetation encroachment | PL-YOLOv8 with directional filters, OBB detection, encroachment metric (GI + TGDI) | TTPLA aerial images (tiling + OBB annotations) | Power line OBB detection and metric-based encroachment scoring suitable for on-board/near-real-time alerts | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Bahreini et al. [49] | 2024 | Detect proximity of trees and power lines | RandLA-Net with DBSCAN and KDTree for post-processing optimizations | Toronto-3D—Point Cloud | Dual focus on power line and vegetation detection with proximity analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Al-Najjar et al. [87] | 2024 | Detect vegetation encroachment on power lines | PointCNN, RandLA-Net, P-BED Algorithm | Mobile and airborne LiDAR Point Clouds | Vegetation and power line classification and proximity analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Zhou et al. [88] | 2024 | Segment power line corridor to detect vegetation hazards | Bilinear Distance Feature Network (BDF-Net) | Power line Corridor Point Cloud (PPCD) | Semantic segmentation of power line corridor, including vegetation risks | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sun et al. [89] | 2024 | Monitor safety in Power line corridors and detect hazards | YOLOX with ConvNeXt backbone, EPNP for 3D ranging | UAV LiDAR, surveillance camera images | Safety distance and hazard detection in power line corridors | ✓ | ✓ | - | - |

| Li et al. [90] | 2024 | Improve accuracy and speed of transmission line detection | Res2Net-YOLACT, Feature Pyramid Network, DIoU-NMS | Transmission Tower/Power Line Aerial-Image (TTPLA) | Transmission line detection for UAV-based inspections | ✓ | ✓ | - | - |

| Sey et al. [91] | 2023 | Monitor vegetation encroachment near power lines | Pix2Pix GAN for NDVI estimation, YoLov5 for power line detection | UAV RGB and multispectral imagery | Vegetation health monitoring, power line detection, proximity assessment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Shi and Kissling [92] | 2023 | Evaluate power line removal methods to improve vegetation metrics | PointCNN, eigenvalue decomposition, hybrid method | Airborne LiDAR | Vegetation height, cover, and vertical variability metrics | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Kyuroson et al. [40] | 2023 | Autonomous segmentation and analysis of power lines and vegetation | Unsupervised ML (DBSCAN, Kd-tree, PCA) | LiDAR—Unlabeled Point Cloud | Power line corridor monitoring for hazard detection and inspection of both vegetation and lines | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| ElGharbawi et al. [93] | 2023 | Estimate canopy heights along power lines for vegetation hazard monitoring | Seg-Net, Res-Net | S2 satellite data, airborne LiDAR | Vegetation height estimation for encroachment monitoring | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ |

| Abongo et al. [44] | 2023 | Efficient detection of distribution power lines | XGBoost with geometric analysis | LiDAR Dataset—Point Cloud | Power line detection in dense vegetation areas | ✓ | ✓ | - | - |

| Gollob et al. [61] | 2023 | Tree detection in forested areas | SLAM algorithm with density-based clustering | Mobile LiDAR— Point Clouds | Detection of individual trees and structural analysis | - | - | ✓ | - |

| Wang et al. [94] | 2023 | Semantic segmentation of transmission corridor | CA-PointNet++ with Coordinate Attention module | UAV LiDAR dataset—Point Cloud | Transmission corridor vegetation and power line segmentation | ✓ | ✓ | - | - |

| Cano-Solis et al. [71] | 2023 | Vegetation encroachment detection in power line corridors | VEPL-Net (DeepLab, U-Net, and VGG-16) | VEPL Dataset (UAV RGB Orthomosaics) | Vegetation and power line segmentation without proximity focus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Oehmcke et al. [48] | 2022 | Predict vegetated area biomass and wood volume | Minkowski-CNN, KPConv, PointNet | Airborne LiDAR—Point Cloud | Vegetated area biomass estimation | ✓ | - | ✓ | - |

| Mahoney et al. [43] | 2022 | Classify and map vegetation types | Stacked ensemble (Random Forest, GBM, ANN) | LiDAR and Landsat satellite imagery | Classification of vegetation types in post-agricultural landscapes | ✓ | - | ✓ | - |

| Almeida et al. [95] | 2022 | Canopy height mapping | Random Forest, CART, Linear Regression | S1 and S2 satellite, airborne LiDAR | Vegetation height estimation in transmission corridors | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mohd Rapheal et al. [42] | 2022 | Detect and classify power lines and poles | Random Forest, LiDAR360 | Mobile Laser Scanning (MLS) data | Power line and electricity pole inventory in suburban areas | ✓ | ✓ | - | - |

| Li et al. [41] | 2022 | Classify tree species in transmission corridors | Random forest, SVM | LiDAR, Aerial imagery | Vegetation species classification in transmission corridors | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ |

| Chen et al. [96] | 2022 | Detection of tree encroachment using and growth models in high voltage power line corridor | Richards’s growth model, two-phase tree encroachment detection algorithm | UAV-borne LiDAR (Fujian, China) | Vegetation encroachment detection and growth prediction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Gazzea et al. [97] | 2021 | Develop a method to monitor vegetation encroachment near powerlines | Semi-supervised segmentation, supervised classification (NDVI, FCN) | WorldView-2, Pleiades-1 satellite images, LiDAR | Monitoring vegetation risks in powerline corridors | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ |

| Qayyum et al. [98] | 2021 | Estimate vegetation threat near power lines | CNN and sparse representation for disparity map estimation | UAV and satellite stereo imagery | Vegetation height and proximity estimation for threat detection | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Kandanaarachchi et al. [99] | 2021 | Detect vegetation ignition risks caused by high impedance faults near power lines | Fourier and Wavelet transforms, decision tree classifiers | Power line Bushfire Safety Program (PBSP) dataset | Early detection of vegetation ignition risk | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Vemula et al. [100] | 2021 | Detect vegetation encroachment near power lines | VE-DETR, Multi-head Attention Transformer, ResNet | UAV-acquired imagery | Vegetation encroachment detection and segmentation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Park et al. [47] | 2021 | Detect power lines and classify vegetation overgrowth for wildfire prevention. | Feature-enhanced CNNs (AlexNet, ResNet18, VGG11), HOG, Hough Transforms | Google Street View images | Classification of vegetation encroachment for fire risk | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Gaha et al. [62] | 2021 | Detect poles and power lines | RANSAC, 3D Parabola Modeling, Cylinder Detection | Mobile LiDAR Point Cloud | Power line and pole detection for distribution networks | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Kattenborn et al. [58] | 2021 | Identify and classify vegetation traits (species, structure) | CNN architectures (VGG, ResNet), multi-modal approaches | High-resolution satellite imagery, UAV, LiDAR | Species classification, segmentation, and structure detection in vegetation | ✓ | - | ✓ | - |

| Diez et al. [57] | 2021 | Review of DL applications for tree detection, species classification, and forest health | CNN (VGG, ResNet, U-Net), transfer learning | UAV-acquired RGB data | Tree detection, species classification, forest health monitoring | ✓ | - | ✓ | - |

| Ma et al. [101] | 2020 | Detect vegetation-related wildfire risks caused by power line faults | Hybrid Step XGBoost (HSXG) | 188 ignition field tests | Vegetation fault detection and ignition risk prediction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Nardinocchi et al. [102] | 2020 | Detect power lines and classify obstacles in power line corridors | 3-D Power Line Obstacle Detection (3-D-PowLOD) algorithm | UAV LiDAR point clouds and airborne surveys | Power line detection and obstacle classification, including vegetation | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

5. Considering Dynamic Aspects of Vegetation

5.1. Growth Dynamics of Trees

Studies About Growth of Trees in Quebec

5.2. Dynamic Impact of Environment

5.2.1. Impact of Wind on Trees

5.2.2. Impact of Snow Weight on Trees

6. Outage Hardening Strategies

- (a)

- Vegetation management (i.e., pruning the trees). Trees are the cause of more than 40% of the weather-related outages in Quebec [159]. The current manual method to identify the lines that require vegetation interventions is time-consuming. Perrette et al. [160] emphasized the significance of evaluating tree vitality before undertaking pruning activities. The study found that trees with diminished vitality tend to develop fewer, shorter, and less voluminous epicormic branches after pruning, which consequently affects the frequency of required maintenance and enhances the safety and efficacy of power distribution systems. Additionally, they employed reduction pruning on principal tree stems as a strategic approach to redirect the growth of scaffold limbs away from power lines, thereby maintaining safe clearance distances and promoting healthy tree growth. Intriguingly, trees with higher vitality exhibited a greater extent of wood discoloration at pruning sites, indicating that although these trees might necessitate less frequent pruning, their management strategies need to account for potential risks associated with their rapid growth and the possibility of more severe wood damage. Dupras et al. [161] emphasized the superiority of pruning over other vegetation management techniques for both urban and rural settings, highlighting its negligible impact on ecosystem services when compared to the more disruptive practice of complete tree removal. The study defined two main strategies for vegetation management in urban areas: (1) total removal of obstructive trees and (2) pruning. These approaches are crucial in reducing the risk of power disruptions and improving the reliability of power distribution networks. Notably, pruning is recognized for its minimal effect on a wide array of ecosystem services provided by trees, woodlands, and forests, establishing it as the optimal choice for preserving ecological balance while managing vegetation near power infrastructure.

- (b)

- Selective undergrounding, (i.e., burying electrical wires underground within a conduit duct bank) is preferable in neighborhoods of high population density because this solution is better from an aesthetic point of view, immune to most weather events, and much safer for the public [162]. The percentages of underground distribution cables in Montreal and the Province of Quebec are 50% and 11%, respectively [163]. Current regulations in most cities in North America do not require undergrounding, and the decisions are taken based on specific urban development projects. This ad hoc mechanism results in social inequity. European countries (e.g., Netherlands and Germany) have made significant commitments to undergrounding. The major concern with undergrounding is its high capital cost and for accessing damaged cables for repair purposes, as well as its vulnerability to floods. This cost should be weighed against the benefits, considering the impact on the economy and society; and suitable regulations and cost-sharing models should be developed to pave the way for undergrounding according to a long-term plan.

- (c)

- Multipurpose Utility Tunnels (MUTs). A MUT can be built under the road right-of-way to host power cables in addition to telecommunication cables, gas pipes, municipal water pipes, heating ducts, etc. MUTs have all the advantages of undergrounding in addition to providing better protection and continuous access to all hosted private and public utilities for inspection, maintenance, and repair [164]. Therefore, MUTs greatly reduce the need for repetitive excavations and road closures to access different types of utilities; and will consequently reduce the related social and environmental costs (e.g., traffic congestion). MUTs are a long-term solution for sustainable and resilient underground utility management [165]. However, like undergrounding, their initial cost is high, which requires good coordination between utility owners for MUT initial and operation cost sharing. Moreover, MUTs are more difficult to build in established cities with open-cut methods. Therefore, innovative construction methods should be used to build them (e.g., micro-tunneling) [166]. MUTs have been built in Europe since the 19th century, and are more common in Japan, Singapore, and China [164].

- (a)

- Outage Prediction Models (OPMs) and Climate Change: Researchers used machine learning (ML) to create OPMs that can forecast power outages caused by weather events [167,168,169,170,171] using a variety of data such as system disturbances reports [172]. The frequency, intensity, and duration of weather-related outages are affected by climate change. Several studies [173,174] associated the failure of electrical poles to climate-driven disasters. A weather-based OPM aiming at increasing resilience was developed by Ahmad et al. [175]. Despite the importance of these studies, none of them fully integrated climate change models with ML-based OPMs.

- (b)

- Automated Vegetation Management: Several studies have considered vegetation management as an approach for reducing the effect of storm-related outages. An ML-based model was developed by Gdanitz et al. [176] for predicting power outages during snow and ice storms to evaluate the effectiveness of Enhanced Tree Trimming (ETT), which is costly because it requires frequent monitoring of tree encroachments [173]. The use of Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) data has been popular in automatically detecting vegetation along power line corridors [177]. The common limitation of most of these studies is the dependency on one source of data for object detection.

- (c)

- Cost–Benefit Analysis (CBA): A CBA considering several power distribution resilience measures was proposed by Zamuda et al. [178]. Furthermore, a framework was introduced by Larsen [179] to predict and monetize the societal costs and benefits of undergrounding both transmission and distribution power cables. The CBA should consider both internal and external costs [180] and the customers’ willingness to pay for undergrounding. Previous studies tried to quantify the social cost based on outage size. Different methods were used to estimate the cost of outages: the production function approach, customer surveys, and case studies. These social costs were estimated for different sectors. The study of Rylander [181] leveraged data spanning a decade, capturing instances of both prolonged and short unforeseen outages to determine the effect of several economic factors. Several studies showed significant social and spatial inequalities in power outage recovery [182,183,184,185,186,187,188]. However, none of the previous studies provided a comprehensive model for comparing hardening solutions.

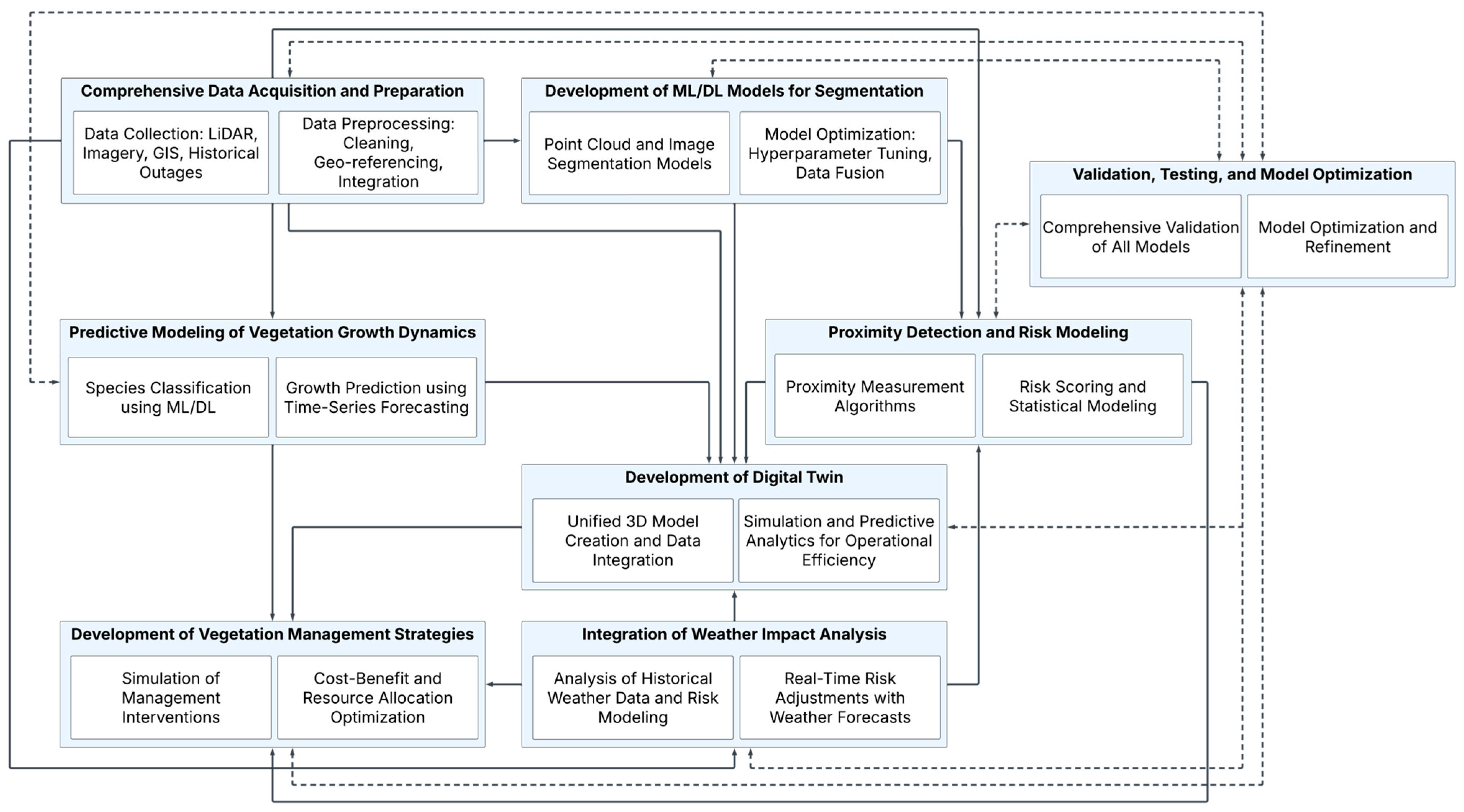

7. Research Roadmap for Enhancing Power Line Resilience Through Vegetation Proximity Detection Using ML/DL Approaches

- (1)

- Comprehensive Data Acquisition and Preparation: A critical foundation for this research is the collection and preparation of high-quality data. Therefore, the following specific steps should be considered: (a) Collect high-resolution LiDAR point cloud data to capture detailed three-dimensional spatial information of vegetation and power lines, which is essential for accurate spatial analysis and modeling; (b) Acquire high-resolution hyperspectral and RGB imagery from drones, satellites, or ground-based cameras to provide detailed visual information necessary for identifying vegetation types and assessing their conditions; (c) Compile existing Geographic Information System (GIS) data to map power line locations, infrastructure details, and environmental features, facilitating spatial correlation analyses; (d) Obtain historical data on power outages related to vegetation to identify patterns, critical factors, and high-risk areas; (e) Apply techniques for data cleaning and noise reduction to remove irrelevant data points and artifacts; and (f) Perform geo-referencing, alignment, and integration of different data sources to create a coherent and comprehensive dataset suitable for analysis. This integrated dataset forms the basis for developing advanced ML/DL models.

- (2)

- Development of Advanced ML/DL Models for Vegetation and Infrastructure Segmentation: Developing sophisticated ML/DL models for vegetation and infrastructure segmentation is a critical component of the research. Therefore, the following specific steps should be considered: (a) Implement and train advanced DL models such as RandLA-Net [49] and Kernel Point Convolution (KPConv) networks [189] for semantic segmentation of LiDAR point clouds or hyperspectral and RGB images, enabling the distinction between vegetation, power lines, poles, and other objects with high precision; (b) Apply model optimization techniques to enhance accuracy while ensuring computational efficiency, making the models practical for large-scale applications; and (c) Use data fusion techniques to combine insights from LiDAR data and imagery, improving segmentation outcomes by capitalizing on the strengths of each data type.

- (3)

- Predictive Modeling of Vegetation Growth Dynamics: Understanding and predicting vegetation growth is essential for proactive management. Therefore, the following specific steps should be considered: (a) Develop ML/DL models to classify tree species based on spectral signatures and morphological features extracted from the data; (b) Ensure accurate species identification, as different species have varying growth rates and patterns [103], and build a comprehensive database of local tree species, including their growth characteristics and environmental preferences, to support growth predictions; (c) Integrate environmental factors such as climate data (temperature, precipitation), soil conditions, and seasonal variations into the growth models to enhance prediction accuracy; and (d) Prioritize integration of publicly available regional datasets, such as those from weather stations or soil surveys, to ensure model generalizability across different geographic areas, and employ time-series forecasting methods, potentially incorporating recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, to predict future vegetation growth and potential encroachment on power lines [190].

- (4)

- Integration of Weather Impact Analysis: Adverse weather conditions can intensify the risks posed by vegetation proximity. Therefore, the following specific steps should be considered: (a) Analyze historical weather data to understand how events such as storms, high winds, and heavy snowfall affect vegetation-related outage risks, identifying patterns and correlations critical for risk assessment; (b) Enhance risk assessment models to account for the combined effects of vegetation proximity and adverse weather conditions, providing a more comprehensive risk profile; and (c) Develop models capable of adjusting risk assessments in real time based on weather forecasts, which involves continuously updating risk levels as weather conditions change using live data to assess the likelihood and impact of outages dynamically [191], enabling proactive measures such as preventive pruning in high-risk scenarios to prevent outages.

- (5)

- Proximity Detection and Risk Modeling: Detecting the proximity of vegetation to power lines and developing models to assess the associated risks is the next vital task. Therefore, the following specific steps should be considered: (a) Develop algorithms to automatically measure the distances between vegetation and power lines using the segmented data, incorporating 3D Euclidean distance calculations to provide precise, quantifiable metrics for risk thresholds; (b) Define critical clearance distances based on industry safety standards to ensure that the analysis aligns with regulatory requirements; and (c) Create a risk scoring model to evaluate the likelihood of vegetation-related outages based on proximity measurements, vegetation characteristics, and historical outage data [192,193], using statistical methods including regression analysis and machine learning classification techniques to identify significant predictors of outage risks and enhance the robustness of the risk assessment model.

- (6)

- Digital Twin Development: Unlike segmentation models, which provide valuable but static insights, a digital twin offers a dynamic and continuously updated virtual model of the physical network. Therefore, the following specific steps should be considered: (a) Integrate multiple data sources, including point clouds, satellite imagery, GIS data, and real-time weather information, to reflect current conditions with high fidelity [194,195]; (b) Leverage the digital twin’s ability to simulate various scenarios that impact the power grid, addressing limitations of real-time proximity detection (which identifies immediate risks but lacks foresight into risk evolution); (c) Incorporate prediction of vegetation growth patterns using advanced machine learning and deep learning algorithms, including forecasts of how environmental factors (such as seasonal changes and weather events) influence vegetation dynamics and proximity to power lines; (d) Enhance risk management by integrating predictive analytics with environmental modeling, including assessments of how adverse weather conditions (like storms or high winds) could exacerbate outage risks due to vegetation interference; (e) Simulate the impact of different vegetation management strategies (such as varying pruning schedules or growth inhibitors) to provide data-driven recommendations for preventive actions, enabling maintenance teams to prioritize high-risk areas, optimize resource allocation, and reduce costs by minimizing unnecessary inspections; (f) Foster improved collaboration across departments by using the digital twin as a centralized platform for up-to-date network status, ensuring consistent information for teams in outage management, vegetation management, and maintenance planning to enhance communication and decision-making; and (g) Design the digital twin with a modular architecture to support incremental updates and integration with existing utility systems, justifying the additional effort over static tools (like Google Earth) by emphasizing its interactive, predictive capabilities for strategic planning and risk mitigation beyond basic detection methods.

- (7)

- Development of Vegetation Management Strategies: Based on the risk assessments and growth predictions, effective vegetation management strategies need to be formulated. Therefore, the following specific steps should be considered: (a) Simulate different vegetation management interventions, such as varying pruning schedules, selective removals, and the use of growth inhibitors, to assess their effectiveness in reducing risks [196]; (b) Conduct economic analyses to evaluate the trade-offs between the costs of interventions and the potential reduction in outage risks, aiding in decision-making for resource allocation; and (c) Develop optimization models, possibly using operations research techniques, to allocate maintenance resources efficiently based on risk levels and priorities, and create scheduling algorithms to plan vegetation management activities at optimal times, considering factors like growth rates, accessibility, and weather conditions, to maximize effectiveness and minimize costs.

- (8)

- Validation, Testing, and Model Optimization: Ensuring the reliability and accuracy of the developed models requires accurate validation and testing procedures. Therefore, the following specific steps should be considered: (a) Conduct field studies to validate the accuracy of the ML/DL models and proximity measurements, involving comparisons of model outputs with actual observations gathered through ground surveys, and perform systematic comparisons against ground truth data to assess performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and Intersection over Union (IoU) for segmentation tasks, as well as mean average precision (mAP) for object detection. Additionally, apply hyperparameter tuning methods to statistically evaluate interactions between parameters like batch size and learning rate, ensuring robust model performance [197]; (b) Perform sensitivity analyses to understand how variations in model parameters affect outputs, helping identify the most influential factors and ensuring model robustness under different conditions, and quantify uncertainties in predictions using statistical methods to enhance model reliability and inform confidence levels in decision-making processes; (c) Apply cross-validation techniques, such as k-fold validation, during testing to assess model performance across diverse subsets of the dataset; (d) Implement pilot deployments of the optimized models and digital twin in selected real-world power line segments to evaluate practical performance and gather user feedback from utility operators; (e) Conduct scalability assessments to identify challenges in expanding to larger networks, such as data volume management and integration with existing monitoring systems; and (f) Explore future extensions like incorporation of emerging sensor technologies to ensure the research evolves with technological advancements, and emphasize knowledge transfer through workshops or reports to stakeholders, promoting adoption in the power sector.

8. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewis, T.; Martin, S.; James, J. Modification of Vegetation Structure and Composition to Reduce Wildfire Risk on a High Voltage Transmission Line. Fire 2025, 8, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.A.A.; Mecheter, I.; Qiblawey, Y.; Fernandez, J.H.; Chowdhury, M.E.; Kiranyaz, S. Deep learning in automated power line inspection: A review. Appl. Energy 2025, 385, 125507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Jiang, J.; Li, J.; Ferreira, V. A review and future directions of techniques for extracting powerlines and pylons from LiDAR point clouds. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 132, 104056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantach, S.; Lutfi, A.; Moradi Tavasani, H.; Ashraf, A.; El-Hag, A.; Kordi, B. Deep Learning in High Voltage Engineering: A Literature Review. Energies 2022, 15, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Dwivedi, R.K.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, V.K. A Review on AI Techniques Applied on Tree Detection in UAV and Remotely Sensed Imagery. In Proceedings of the 2022 11th International Conference on System Modeling & Advancement in Research Trends (SMART), Moradabad, India, 16–17 December 2022; pp. 1446–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibitoye, O.T.; Onibonoje, M.O.; Dada, J.O. Machine Learning Based Techniques for Fault Detection in Power Distribution Grid: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics (ICon EEI), Pekanbaru, Indonesia, 19–20 October 2022; pp. 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodayar, M.; Liu, G.; Wang, J.; Khodayar, M.E. Deep learning in power systems research: A review. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 7, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroun, F.M.E.; Deros, S.N.M.; Din, N.M. A review of vegetation encroachment detection in power transmission lines using optical sensing satellite imagery. Int. J. Adv. Trends Comput. Sci. Eng. 2020, 9, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, O.A.; Ouahada, K.; Abu-Mahfouz, A.M. A Review of Machine Learning Approaches to Power System Security and Stability. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 113512–113531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhu, Z.; Hammad, A. Critical review and road map of automated methods for earthmoving equipment productivity monitoring. Int. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2022, 36, 03122001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Science and Technology Studies, Leiden University, The Netherlands. VOSviewer. 2024. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/ (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- K-Synth Srl, Academic Spin-Off of the University of Naples Federico. BIBLIOMETRIX. 2024. Available online: https://www.bibliometrix.org/home/ (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Zhu, J.-J.; Liu, Z.-G.; Li, X.-F.; Matsuzaki, T.; Gonda, Y. Review: Effects of wind on trees. J. For. Res. 2004, 15, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzsch, H. The course of tree growth. Theory and reality. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 478, 118508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elaal, E.-S.; Mills, J.E.; Ma, X. A review of transmission line systems under downburst wind loads. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2018, 179, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haes Alhelou, H.; Hamedani-Golshan, M.; Njenda, T.; Siano, P. A Survey on Power System Blackout and Cascading Events: Research Motivations and Challenges. Energies 2019, 12, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Saket, R.K.; Dheer, D.K.; Holm-Nielsen, J.B.; Sanjeevikumar, P. Reliability enhancement of electrical power system including impacts of renewable energy sources: A comprehensive review. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2020, 14, 1799–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hou, H.; Liang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wei, R.; Liu, S. Review of risk analysis methods for failure scenario in power system under typhoon disasters. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th Asia Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering (ACPEE), Chongqing, China, 8–11 April 2021; pp. 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omogoye, O.S.; Folly, K.A.; Awodele, K.O. Review of Proactive Operational Measures for the Distribution Power System Resilience Enhancement Against Hurricane Events. In Proceedings of the 2021 Southern African Universities Power Engineering Conference/Robotics and Mechatronics/Pattern Recognition Association of South Africa (SAUPEC/RobMech/PRASA), Potchefstroom, South Africa, 27–29 January 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.D.; Al-Ismail, F.S.M.; Shafiullah, M.; Al-Sulaiman, F.A.; El-Amin, I.M. Grid Integration Challenges of Wind Energy: A Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 10857–10878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, O.; Ebakumo Thomas, O. Effect of Wind Environment on High Voltage Transmission Lines Span. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Appl. 2019, 8, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttle, R.; Kane, B.; Bloniarz, D. Comparing the Structure, Function, Value, and Risk of Managed and Unmanaged Trees along Rights-of-Way and Streets in Massachusetts. Forests 2022, 13, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yang, Z.; Ding, W.; Buck-Sorlin, G. Physics-based algorithm to simulate tree dynamics under wind load. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2020, 13, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, R.H.; Sills, E.; Liu, T.; Pattanayak, S. The influence of forest management on vulnerability of forests to severe weather. In Advances in Threat Assessment and Their Application to Forest and Rangeland Management; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest and Southern Research Stations: Portland, OR, USA, 2010; pp. 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Daeli, A.; Mohagheghi, S. Power Grid Infrastructural Resilience against Extreme Events. Energies 2022, 16, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, A. Optimizing power system operations for extreme weather events: A review. Manag. J. Electr. Eng. 2022, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jufri, F.H.; Widiputra, V.; Jung, J. State-of-the-art review on power grid resilience to extreme weather events: Definitions, frameworks, quantitative assessment methodologies, and enhancement strategies. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawluk, R.E.; Chen, Y.; She, Y. Photovoltaic electricity generation loss due to snow—A literature review on influence factors, estimation, and mitigation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 107, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.A.; Chen, T.; Su, W.; Jin, T. Proactive Resilience of Power Systems Against Natural Disasters: A Literature Review. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 163778–163795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahzarnia, M.; Moghaddam, M.P.; Baboli, P.T.; Siano, P. A Review of the Measures to Enhance Power Systems Resilience. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 14, 4059–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Poudyal, A.; Poudel, S.; Dubey, A.; Wang, Z. Resilience assessment and planning in power distribution systems:Past and future considerations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 189, 113991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rourk, C. A review of lightning-related operating events at nuclear power plants. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 1994, 9, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holle, R.L. Some aspects of global lightning impacts. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Lightning Protection (ICLP), Shanghai, China, 11–18 October 2014; pp. 1390–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskliukova, E.; Belko, D. Review of Lightning Impacts on Power Supply of Productive and Extractive Industry in South Africa and Such Ways of Production Loss Mitigation as Installation of Line Lightning Protection Devices. In Proceedings of the 2022 36th International Conference on Lightning Protection (ICLP), Cape Town, South Africa, 2–7 October 2022; pp. 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doostan, M.; Chowdhury, B. Predicting Lightning-Related Outages in Power Distribution Systems: A Statistical Approach. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 84541–84550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawi, I.M.; Abidin Ab Kadir, M.Z.; Gomes, C.; Azis, N. A Case Study on 500 kV Line Performance Related to Lightning in Malaysia. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2018, 33, 2180–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpov, E.; Katz, E. Characterization of Local Environmental Data and Lightning-Caused Outages in the IECo Transmission-Line Network. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2016, 31, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotti, A.; Mottola, F.; Pierno, A.; Proto, D. Statistical features of lightning-induced voltages. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion (SPEEDAM), Amalfi, Italy, 20–22 June 2018; pp. 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaglio, M.A.; Küster, K.K.; França Santos, S.L.; Ribeiro Barrozo Toledo, L.F.; Piantini, A.; Lazzaretti, A.E.; De Mello, L.G.; Da Silva Pinto, C.L. Evaluation of lightning-related faults that lead to distribution network outages: An experimental case study. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2019, 174, 105848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyuroson, A.; Koval, A.; Nikolakopoulos, G. Autonomous Point Cloud Segmentation for Power Lines Inspection in Smart Grid. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2023, 56, 11754–11761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, R.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Duan, Y. Classification of Transmission Line Corridor Tree Species Based on Drone Data and Machine Learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Rapheal, M.S.A.; Farhana, A.; Mohd Salleh, M.R.; Abd Rahman, M.Z.; Majid, Z.; Musliman, I.A.; Abdullah, A.F.; Abd Latif, Z. Machine Learning Approach for Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB) Overhead Powerline and Electricity Pole Inventory Using Mobile Laser Scanning Data. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 46, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, M.J.; Johnson, L.K.; Guinan, A.Z.; Beier, C.M. Classification and mapping of low-statured shrubland cover types in post-agricultural landscapes of the US Northeast. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 7117–7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abongo, D.A.; Gaha, M.; Cherif, S.; Jaafar, W.; Houle, G.; Buteau, C. A novel framework for distribution power lines detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Gammarth, Tunisia, 9–12 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Zhang, W.; Wei, X. A review on weed detection using ground-based machine vision and image processing techniques. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 158, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakos, K.; Busato, P.; Moshou, D.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. Machine Learning in Agriculture: A Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Rajabi, F.; Weber, R. Slash or burn: Power line and vegetation classification for wildfire prevention. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.03804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehmcke, S.; Li, L.; Revenga, J.C.; Nord-Larsen, T.; Trepekli, K.; Gieseke, F.; Igel, C. Deep learning-based 3D point cloud regression for estimating forest biomass. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 1–4 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bahreini, F.; Hammad, A.; Nick-Bakht, M. Point Cloud-based Computer Vision Framework for Detecting Proximity of Trees to Power Distribution Lines. In Proceedings of the ISARC Proceedings—The International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction, Lille, France, 3–5 June 2024; IAARC Publications: Lille, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bahreini, F.; Nik-Bakht, M.; Hammad, A.; Gaha, M. Developing Computer Vison-based Digital Twin for Vegetation Management Near Power Distribution Networks. In Proceedings of the 42nd International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction; International Association on Automation and Robotics in Construction, Montreal, QC, Canada, 28–31 July 2025; pp. 1174–1181. [Google Scholar]

- Ozcanli, A.K.; Yaprakdal, F.; Baysal, M. Deep learning methods and applications for electrical power systems: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 7136–7157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.N.; Jenssen, R.; Roverso, D. Automatic autonomous vision-based power line inspection: A review of current status and the potential role of deep learning. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 99, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Tan, Y.; Xue, J.; Lu, K. Notice of Violation of IEEE Publication Principles: Recent Advances in 3D Object Detection in the Era of Deep Neural Networks: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 2947–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Gao, R.; Jin, Z.; Wang, X. Recent advances in the application of deep learning methods to forestry. Wood Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 1171–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, A.; Walsh, K.B.; Wang, Z.; McCarthy, C. Deep learning—Method overview and review of use for fruit detection and yield estimation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 162, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, S.; Xie, L.; Ji, M.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Yang, F.; Qiu, D. Real-time powerline corridor inspection by edge computing of UAV Lidar data. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 42, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, Y.; Kentsch, S.; Fukuda, M.; Caceres, M.L.L.; Moritake, K.; Cabezas, M. Deep Learning in Forestry Using UAV-Acquired RGB Data: A Practical Review. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattenborn, T.; Leitloff, J.; Schiefer, F.; Hinz, S. Review on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) in vegetation remote sensing. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 173, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Durairaj, S. Review of Deep Learning Algorithms for Urban Remote Sensing UsingUnmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Recent Adv. Comput. Sci. Commun. 2024, 17, e081223224285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendu, B.; Mbuli, N. State-of-the-Art Review on the Application of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in Power Line Inspections: Current Innovations, Trends, and Future Prospects. Drones 2025, 9, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollob, C.; Krassnitzer, R.; Ritter, T.; Tockner, A.; Erber, G.; Kühmaier, M.; Hönigsberger, F.; Varch, T.; Holzinger, A.; Stampfer, K.; et al. Measurement of Individual Tree Parameters with Carriage-Based Laser Scanning in Cable Yarding Operations. Croat. J. For. Eng. J. Theory Appl. For. Eng. 2023, 44, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaha, M.; Jaafar, W.; Fakhfekh, J.; Houle, G.; Abderrazak, J.B.; Bourgeois, M. Anew lidar-based approach for poles and distribution lines detection and modelling. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2021, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-López, D.; López-Rebollo, J.; Moreno, M.A.; Gonzalez-Aguilera, D. Automatic Processing for Identification of Forest Fire Risk Areas along High-Voltage Power Lines Using Coarse-to-Fine LiDAR Data. Forests 2023, 14, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribov, A.; Duri, K. Reconstruction of power lines from point clouds. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, San José, CA, USA, 21–26 August 2023; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Amado, M.; Lopes, F.; Dias, A.; Martins, A. LiDAR-based power assets extraction based on point cloud data. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Autonomous Robot Systems and Competitions, Santa Maria da Feira, Portugal, 28–29 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Awrangjeb, M. Extraction of power line pylons and wires using airborne lidar data at different height levels. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guo, Y. Application of LiDAR technology in power line inspection. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 382, 052025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horning, N. Land cover mapping with ultra-high-resolution aerial imagey. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 6, 429–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Qin, N.; Ma, L.; Li, Y.; Du, J.; Cai, G.; Yang, K.; Li, J. Toronto-3D: A large-scale mobile LiDAR dataset for semantic segmentation of urban roadways. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelfattah, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, S. Ttpla: An aerial-image dataset for detection and segmentation of transmission towers and power lines. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.10032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Solis, M.; Ballesteros, J.R.; Sanchez-Torres, G. VEPL-Net: A Deep Learning Ensemble for Automatic Segmentation of Vegetation Encroachment in Power Line Corridors Using UAV Imagery. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varney, N.; Asari, V.K.; Graehling, Q. DALES: A large-scale aerial LiDAR data set for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 186–187. [Google Scholar]

- Pascucci, S.; Pignatti, S.; Casa, R.; Darvishzadeh, R.; Huang, W. Special Issue “Hyperspectral Remote Sensing of Agriculture and Vegetation”. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Coppo, M.; Bignucolo, F.; Turri, R. Losses management strategies in active distribution networks: A review. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2018, 163, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni-Bonab, S.M.; Hajebrahimi, A.; Kamwa, I.; Moeini, A. Transmission and distribution co-simulation: A review and propositions. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2020, 14, 4631–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, L.; Cossent, R.; Chaves-Ávila, J.P.; Gómez San Román, T. Transmission and distribution coordination in power systems with high shares of distributed energy resources providing balancing and congestion management services. WIREs Energy Environ. 2019, 8, e357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskin, M.; Domijan, A.; Grinberg, I. Impact of distributed generation on the protection systems of distribution networks: Analysis and remedies—Review paper. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2020, 14, 5944–5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajora, G.L.; Sanz-Bobi, M.A.; Domingo, C.M. Application of Machine Learning Methods for Asset Management on Power Distribution Networks. Emerg. Sci. J. 2022, 6, 905–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, S.; Majumder, S.; Viswanathan, A.; Guttal, V. Clustering and correlations: Inferring resilience from spatial patterns in ecosystems. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2019, 10, 2079–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Khan, S.S. Survey of State-of-the-Art Mixed Data Clustering Algorithms. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 31883–31902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchórzewski, J.; Kania, T. Cluster analysis on the example of work data of the National Power System. Part 2. Research and selected results. Stud. Inform. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2021, 23, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H. Agricultural Soil Data Analysis Using Spatial Clustering Data Mining Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 13th International Conference on Computer Research and Development (ICCRD), Beijing, China, 5–7 January 2021; pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Shi, K.; Cheng, X.; Wu, X.; Yang, J.; Pang, L.; Shi, Y. Research on UAV-LiDAR-Based Detection and Prediction of Tree Risks on Transmission Lines. Forests 2025, 16, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harini, B.; Gouri, M.; Manju, M. AI-Driven Vegetation Monitoring and Fire Risk Mitigation for Wildfire Prevention and Powerline Safety. In Proceedings of the 2025 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Systems, Advanced Computing and Communication (ISACC), Online, 27–28 February 2025; pp. 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Najjar, A.; Amini, M.; Green, J.R.; Kwamena, F. LineShield—A Generalized LiDAR Pipeline for Automated Vegetation Encroachment Detection on Powerlines. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), London, UK, 25–28 May 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, S.; He, L.; Atici, S.F.; Cetin, A.E. Advanced YOLO-based Real-time Power Line Detection for Vegetation Management. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2025, 40, 2142–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najjar, A.; Amini, M.; Rajan, S.; Green, J.R. Identifying Areas of High-risk Vegetation Encroachment on Electrical Powerlines using Mobile and Airborne Laser Scanned Point Clouds. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 22129–22143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Feng, Z.; Chen, C.; Yu, F. Bilinear Distance Feature Network for Semantic Segmentation in PowerLine Corridor Point Clouds. Sensors 2024, 24, 5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Q.; Tian, K. Transmission Line Detection Method Based on Improved Res2Net-YOLACT Model; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Liu, P.; Liang, Y.; Shuang, F.; Huang, J. Safety monitoring method for powerline corridors based on single-stage detector and visual matching. High Volt. 2024, 9, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sey, N.E.N.; Amo-Boateng, M.; Domfeh, M.K.; Kabo-Bah, A.T.; Antwi-Agyei, P. Deep learning-based framework for vegetation hazard monitoring near powerlines. Spat. Inf. Res. 2023, 31, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Kissling, W.D. Performance, effectiveness and computational efficiency of powerline extraction methods for quantifying ecosystem structure from light detection and ranging. GIScience Remote Sens. 2023, 60, 2260637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElGharbawi, T.; Susaki, J.; Chureesampant, K.; Arunplod, C.; Thanyapraneedkul, J.; Limlahapun, P.; Suliman, A. Performance evaluation of convolution neural networks in canopy height estimation using sentinel 2 data, application to Thailand. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 44, 1726–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, L.; Wu, S.; Zu, S.; Song, B. Semantic Segmentation of Transmission Corridor 3D Point Clouds Based on CA-PointNet++. Electronics 2023, 12, 2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.; Gerente, J.; Prazeres Campos, J.; Caruso Gomes Junior, F.; Providelo, L.A.; Marchiori, G.; Chen, X. Canopy Height Mapping by Sentinel 1 and 2 Satellite Images, Airborne LiDAR Data, and Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, J.; Liao, X. Early detection of tree encroachment in high voltage powerline corridor using growth model and UAV-borne LiDAR. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 108, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzea, M.; Pacevicius, M.; Dammann, D.O.; Sapronova, A.; Lunde, T.M.; Arghandeh, R. Automated power lines vegetation monitoring using high-resolution satellite imagery. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 37, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, A.; Razzak, I.; Malik, A.S.; Anwar, S. Fusion of CNN and sparse representation for threat estimation near power lines and poles infrastructure using aerial stereo imagery. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 168, 120762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandanaarachchi, S.; Anantharama, N.; Munoz, M.A. Early detection of vegetation ignition due to powerline faults. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 36, 1324–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemula, S.; Frye, M. Multi-head attention based transformers for vegetation encroachment over powerline corriders using UAV. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/AIAA 40th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), San Antonio, TX, USA, 3–7 October 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Cheng, J.C.; Jiang, F.; Gan, V.J.; Wang, M.; Zhai, C. Real-time detection of wildfire risk caused by powerline vegetation faults using advanced machine learning techniques. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2020, 44, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardinocchi, C.; Balsi, M.; Esposito, S. Fully automatic point cloud analysis for powerline corridor mapping. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 8637–8648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creber, G.T. Tree rings: A natural data-storage system. Biol. Rev. 1977, 52, 349–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, S.; Tysklind, N.; Heuertz, M.; Hérault, B. Selection in space and time: Individual tree growth is adapted to tropical forest gap dynamics. Mol. Ecol. 2022, 34, e16392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzold, S.; Sterck, F.; Bose, A.K.; Braun, S.; Buchmann, N.; Eugster, W.; Gessler, A.; Kahmen, A.; Peters, R.L.; Vitasse, Y.; et al. Number of growth days and not length of the growth period determines radial stem growth of temperate trees. Ecol. Lett. 2022, 25, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmking, M.; Van Der Maaten-Theunissen, M.; Van Der Maaten, E.; Scharnweber, T.; Buras, A.; Biermann, C.; Gurskaya, M.; Hallinger, M.; Lange, J.; Shetti, R.; et al. Global assessment of relationships between climate and tree growth. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 3212–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, S.L.; Perring, M.P.; Vanhellemont, M.; Depauw, L.; Van Den Bulcke, J.; Brūmelis, G.; Brunet, J.; Decocq, G.; Den Ouden, J.; Härdtle, W.; et al. Environmental drivers interactively affect individual tree growth across temperate European forests. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teets, A.; Fraver, S.; Weiskittel, A.R.; Hollinger, D.Y. Quantifying climate–growth relationships at the stand level in a mature mixed-species conifer forest. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 3587–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trotsiuk, V.; Babst, F.; Grossiord, C.; Gessler, A.; Forrester, D.I.; Buchmann, N.; Schaub, M.; Eugster, W. Tree growth in Switzerland is increasingly constrained by rising evaporative demand. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 2981–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, N.G.; Allen, C.D.; Anderson-Teixeira, K.; Aukema, B.H.; Bond-Lamberty, B.; Chini, L.; Clark, J.S.; Dietze, M.; Grossiord, C.; Hanbury-Brown, A.; et al. Pervasive shifts in forest dynamics in a changing world. Science 2020, 368, eaaz9463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Fang, S.; Wang, Q.-W.; Liu, H.; Lin, F.; Ye, J.; Hao, Z.; Wang, X.; Fortunel, C. Ontogeny influences tree growth response to soil fertility and neighbourhood crowding in an old-growth temperate forest. Ann. Bot. 2023, 131, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanmiguel-Vallelado, A.; Camarero, J.J.; Morán-Tejeda, E.; Gazol, A.; Colangelo, M.; Alonso-González, E.; López-Moreno, J.I. Snow dynamics influence tree growth by controlling soil temperature in mountain pine forests. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 296, 108205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochner, M.; Bugmann, H.; Nötzli, M.; Bigler, C. Tree growth responses to changing temperatures across space and time: A fine-scale analysis at the treeline in the Swiss Alps. Trees 2018, 32, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijowska-Oberc, J.; Staszak, A.M.; Kamiński, J.; Ratajczak, E. Adaptation of Forest Trees to Rapidly Changing Climate. Forests 2020, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciceu, A.; Popa, I.; Leca, S.; Pitar, D.; Chivulescu, S.; Badea, O. Climate change effects on tree growth from Romanian forest monitoring Level II plots. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson-Teixeira, K.J.; Herrmann, V.; Rollinson, C.R.; Gonzalez, B.; Gonzalez-Akre, E.B.; Pederson, N.; Alexander, M.R.; Allen, C.D.; Alfaro-Sánchez, R.; Awada, T.; et al. Joint effects of climate, tree size, and year on annual tree growth derived from tree-ring records of ten globally distributed forests. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Assessing Maple Species in The Annex Neighbourhood from 2011 to 2022. 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1807/127533 (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Jutras, P.; Prasher, S.O.; Mehuys, G.R. Appraisal of key biotic parameters affecting street tree growth. J. Arboric. 2010, 36, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Millet, J.; Bouchard, A. Architecture of silver maple and its response to pruning near the power distribution network. Can. J. For. Res. 2003, 33, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, D.W.; Meyer, S.P. Characteristics and distribution of potential ash tree hosts for emerald ash borer. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 213, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkins, J.B.; Swanson, B.T. Susceptibility of ‘Skyline’ Honeylocust to Cankers Caused by Nectria cinnabarina Influenced by Nursery Field Management System. J. Environ. Hortic. 1997, 15, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon III, D.H. A case study of honeylocust in the Tennessee valley region. In Tree Crops for Energy Co-Production on Farms; National Technical Information Service SERICP-622-1086; U.S. Solar Energy Research Institute: Golden, CO, USA, 1980; pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bukharina, I.; Vedernikov, K.; Kamasheva, A.; Alekseenko, A.; Pashkov, E. Ecological and biological features of Colorado spruce (Picea pungens Engelm.) in urban environment. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2014, 13, 367–371. [Google Scholar]

- Postma, M. Assessing the Introduction and Age of the Acer platanoides (Norway Maple) Invasion Within Wilket Creek Ravine in Toronto, Ontario. Master’s Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Limoges, S.; Pham, T.-T.-H.; Apparicio, P. Growing on the street: Multilevel correlates of street tree growth in Montreal. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Krause, C.; Fenton, N.J.; Morin, H. Unveiling the Diversity of Tree Growth Patterns in Boreal Old-Growth Forests Reveals the Richness of Their Dynamics. Forests 2020, 11, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavardès, R.D.; Balducci, L.; Bergeron, Y.; Grondin, P.; Poirier, V.; Morin, H.; Gennaretti, F. Greater tree species diversity and lower intraspecific competition attenuate impacts from temperature increases and insect epidemics in boreal forests of western Quebec, Canada. Can. J. For. Res. 2023, 53, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, E.A.; Bergeron, Y.; Girardin, M.P.; Drobyshev, I. Contrasting Growth Response of Jack Pine and Trembling Aspen to Climate Warming in Quebec Mixedwoods Forests of Eastern Canada Since the Early Twentieth Century. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2021, 126, e2020JG005873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, G.; Achim, A.; Pothier, D. A dendrochronological reconstruction of sugar maple growth and mortality dynamics in partially cut northern hardwood forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 437, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, L.; Prévost, M. Canopy disturbance and intertree competition: Implications for tree growth and recruitment in two yellow birch–conifer stands in Quebec, Canada. J. For. Res. 2013, 18, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Cairo, E.; Krause, C.; Deslauriers, A. Growth and basic wood properties of black spruce along an alti-latitudinal gradient in Quebec, Canada. Ann. For. Sci. 2015, 72, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutras, P.; Prasher, S.O.; Mehuys, G.R. Artificial Neural Network Prediction of Street Tree Growth Patterns. Trans. ASABE 2010, 53, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutras, P.; Prasher, S.; Dutilleul, P. Identification of Significant Street Tree Inventory Parameters Using Multivariate Statistical Analyses. Arboric. Urban For. 2009, 35, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telewski, F. Wind-induced physiological and developmental responses in trees. In Wind and Trees; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Ham, Y. Measuring the Distance between Trees and Power Lines under Wind Loads to Assess the Heightened Potential Risk of Wildfire. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, G.; Kim, J.-J.; Choi, W. Computational fluid dynamics simulation of tree effects on pedestrian wind comfort in an urban area. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 56, 102086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Défossez, P.; Dupont, S. A root-to-foliage tree dynamic model for gusty winds during windstorm conditions. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 287, 107949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, A.; Jelonek, T.; Pazdrowski, W.; Grzywiński, W.; Mania, P.; Tomczak, K. The Effects of Wind Exposure on Scots Pine Trees: Within-Stem Variability of Wood Density and Mechanical Properties. Forests 2020, 11, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hua, J.; Kang, M.; Wang, X.; Fan, X.-R.; Fourcaud, T.; De Reffye, P. Stronger wind, smaller tree: Testing tree growth plasticity through a modeling approach. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 971690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.; Gardiner, B.; Sellier, D. Tree Mechanics and Wind Loading. In Plant Biomechanics; Geitmann, A., Gril, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; Shenkin, A.; Kalyan, B.; Zionts, J.; Calders, K.; Origo, N.; Disney, M.; Burt, A.; Raumonen, P.; Malhi, Y. A New Architectural Perspective on Wind Damage in a Natural Forest. Front. For. Glob. Change 2019, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarero, J.J.; Colangelo, M.; Gazol, A.; Pizarro, M.; Valeriano, C.; Igual, J.M. Effects of Windthrows on Forest Cover, Tree Growth and Soil Characteristics in Drought-Prone Pine Plantations. Forests 2021, 12, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisans, O.; Matisons, R.; Rust, S.; Burnevica, N.; Bruna, L.; Elferts, D.; Kalvane, L.; Jansons, A. Presence of Root Rot Reduces Stability of Norway Spruce (Picea abies): Results of Static Pulling Tests in Latvia. Forests 2020, 11, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dèfossez, P.; Rajaonalison, F.; Bosc, A. How wind acclimation impacts Pinus pinaster growth in comparison to resource availability. For. Int. J. For. Res. 2022, 95, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojatimalekshah, A.; Uhlmann, Z.; Glenn, N.F.; Hiemstra, C.A.; Tennant, C.J.; Graham, J.D.; Spaete, L.; Gelvin, A.; Marshall, H.-P.; McNamara, J.P.; et al. Tree canopy and snow depth relationships at fine scales with terrestrial laser scanning. Cryosphere 2021, 15, 2187–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duperat, M.; Gardiner, B.; Ruel, J.-C. Wind and Snow Loading of Balsam Fir during a Canadian Winter: A Pioneer Study. Forests 2020, 11, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Shi, F.; Zhao, S.; Yang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, S.; et al. Compensation effect of winter snow on larch growth in Northeast China. Clim. Change 2021, 164, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, A.; Minamino, R.; Sawakami, K.; Katsushima, T.; Tateno, M. Monitoring bending stress of trees during a snowy period using strain gauges. Bull. Glaciol. Res. 2020, 38, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Ciais, P.; Li, Y.; Xu, C.; Babst, F.; Guo, W.; Hao, B.; Wang, P.; et al. Uneven winter snow influence on tree growth across temperate China. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinmann, A.B.; Susser, J.R.; Demaria, E.M.C.; Templer, P.H. Declines in northern forest tree growth following snowpack decline and soil freezing. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, L.; Bolatov, K.; Yuan, Y.; Shang, H.; Yu, S.; Zhang, T.; Bagila, M.; Bolatova, A.; Zhang, R. The Spatially Inhomogeneous Influence of Snow on the Radial Growth of Schrenk Spruce (Picea schrenkiana Fisch. et Mey.) in the Ili-Balkhash Basin, Central Asia. Forests 2022, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Nateghi, R.; Hastak, M. A multi-hazard approach to assess severe weather-induced major power outage risks in the U.S. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 175, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, E.; Nazemi, A.; Adamowski, J.; Nguyen, T.-H.; Van-Nguyen, V.-T. Quantile-based downscaling of rainfall extremes: Notes on methodological functionality, associated uncertainty and application in practice. Adv. Water Resour. 2019, 131, 103371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Enhancing the Resilience of the Nation’s Electricity System; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, O.M.; Zulqarnain, M.; Butt, T.M. Recent advancement in smart grid technology: Future prospects in the electrical power network. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydro-Québec. Managing Tree and Branch Debris. 2024. Available online: https://www.hydroquebec.com/safety/vegetation/managing-tree-branch-debris.html (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- City of Montreal, Reconstruction of Underground Infrastructure in Griffintown. 2021. Available online: https://montreal.ca/en/articles/reconstruction-underground-infrastructure-griffintown-12850 (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Lim, J. Common Service Tunnels & District Cooling-Singapore Marina Bay City. 2012. Available online: http://blog.japhethlim.com/index.php/2012/05/03/common-service-tunnels-singapore-marina-bay-city/ (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Hydro Quebec. Trees and the Power System, Hydro-Québec. 2024. Available online: https://pannes.hydroquebec.com/poweroutages/understand-and-prevent/vegetation.html (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Perrette, G.; Delagrange, S.; Ramirez, J.A.; Messier, C. Optimizing reduction pruning under electrical lines: The influence of tree vitality before pruning on traumatic responses. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 63, 127139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupras, J.; Patry, C.; Tittler, R.; Gonzalez, A.; Alam, M.; Messier, C. Management of vegetation under electric distribution lines will affect the supply of multiple ecosystem services. Land Use Policy 2016, 51, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Nour, G.; Gauthier, F.; Diallo, I.; Komljenovic, D.; Vaillancourt, R.; Côté, A. Development of a Resilience Management Framework Adapted to Complex Asset Systems: Hydro-Québec Research Chair on Asset Management. In 14th WCEAM Proceedings; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydro-Quebec. Underground Distribution Lines, Hydro-Québec. Available online: http://www.hydroquebec.com/learning/distribution/voie-souterraine.html (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Luo, Y.; Alaghbandrad, A.; Genger, T.K.; Hammad, A. History and recent development of multi-purpose utility tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 103, 103511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genger, T.K.; Luo, Y.; Hammad, A. Multi-criteria spatial analysis for location selection of multi-purpose utility tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 115, 104073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorjam, S.; Hammad, A. Discrete Event Simulation of Multi-purpose Utility Tunnels Construction Using Microtunneling. In Proceedings of the 38th ISARC, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2–4 November 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.L.; Koukoula, M.; Anagnostou, E. Influence of the Characteristics of Weather Information in a Thunderstorm-Related Power Outage Prediction System. Forecasting 2021, 3, 541–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrai, D.; Predicting Weather-Caused Power Outages: Technique Development, Evaluation, Applications. Doctoral Dissertations, 2019. Available online: https://digitalcommons.lib.uconn.edu/dissertations/2110 (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Kor, Y.; Reformat, M.Z.; Musilek, P. Predicting weather-related power outages in distribution grid. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Montreal, QC, Canada, 2–6 August 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongus, D.; Brumen, M.; Žlaus, D.; Kohek, Š.; Tomažič, R.; Kerin, U. A Complete Environmental Intelligence System for LiDAR-Based Vegetation Management in Power-Line Corridors. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemazkoor, N.; Rachunok, B.; Chavas, D.R.; Staid, A.; Louhghalam, A.; Nateghi, R. Hurricane-induced power outage risk under climate change is primarily driven by the uncertainty in projections of future hurricane frequency. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NERC. Event Reports. 2023. Available online: https://www.nerc.com/pa/rrm/ea/Pages/Major-Event-Reports.aspx (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Jakhar, R. A Review on the Impacts of Climate Change on the Power Systems. Artic. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2023, 12, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkika, A.V.; Zacharis, E.A.; Lekkas, E.L.; Lozios, S.G.; Parcharidis, I.A. Climate Change Adaptation Management Pathway for Overhead Electricity Pole Systems of Distribution Networks. In Proceedings of the 2nd World Conference onSustainability, Energy and Environment, Berlin, Germany, 9–11 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.; Covatariu, A.; Ramana, M.V. A stormy future? Financial impact of climate change-related disruptions on nuclear power plant owners. Util. Policy 2023, 81, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gdanitz, N.; Khaliq, L.H.A.; Ahiagble, A.P.; Janzen, S.; Maass, W. POWOP: Weather-based Power Outage Prediction. In Intelligent Systems and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, D.; Witharana, C. Roadside Forest Modeling Using Dashcam Videos and Convolutional Neural Nets. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 2022, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamuda, C.D.; Larsen, P.H.; Collins, M.T.; Bieler, S.; Schellenberg, J.; Hees, S. Monetization methods for evaluating investments in electricity system resilience to extreme weather and climate change. Electr. J. 2019, 23, 106641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, P.H. A method to estimate the costs and benefits of undergrounding electricity transmission and distribution lines. Energy Econ. 2016, 60, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, E.; Glass, V. Underground power lines can be the least cost option when study biases are corrected. Electr. J. 2019, 32, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rylander, E. Economic Repercussions of Power Outages for Swedish Electrical Distribution Companies. 2023. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1771989&dswid=6979 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Coleman, N.; Esmalian, A.; Lee, C.C.; Gonzales, E.; Koirala, P.; Mostafavi, A. Energy inequality in climate hazards: Empirical evidence of social and spatial disparities in managed and hazard-induced power outages. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 92, 104491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, A.X.; Kurtz, L.C.; Hondula, D.M.; Meerow, S.; Gall, M. Understanding the social impacts of power outages in North America: A systematic review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 053004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcotullio, P.; Diko, O.B.; Lane, K.; Tipaldo, J.; Yoon, L.; Knowlton, K.; Anand, G.; Matte, T. Local Power Outages, Heat, and Community Characteristics in New York City. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bista, R.; Chhetri, P.K. Energy and Climate Change Issues Around CSUDH. CSU J. Sustain. Clim. Change 2023, 2, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, J.S.; Cooke, A.L.; Kazimierczuk, K.; Tapio, R.M.; Peacock, J.; King, A.G. Emerging Best Practices for Electric Utility Planning with Climate Variability: A Resource for Utilities and Regulators; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Do, V.; McBrien, H.; Flores, N.M.; Northrop, A.J.; Schlegelmilch, J.; Kiang, M.V. Spatiotemporal distribution of power outages with climate events and social vulnerability in the USA. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, W.; Lu, Q.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, W. Modeling Tree Damages and Infrastructure Disruptions under Strong Winds for Community Resilience Assessment. ASCE ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Civ. Eng. 2023, 9, 04022057-1-27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.; Qi, C.R.; Deschaud, J.-E.; Marcotegui, B.; Goulette, F.; Guibas, L.J. KPConv: Flexible and Deformable Convolution for Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Du, W.; Lei, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, N. NDVI Forecasting Model Based on the Combination of Time Series Decomposition and CNN–LSTM. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 37, 1481–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanian, P.; Zhang, B.; Dokic, T.; Kezunovic, M. Predictive risk analytics for weather-resilient operation of electric power systems. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J. Statistical Modeling for the Effects of Vegetative Growth on Power Distribution System Reliability. Front. Appl. Math. Stat. 2021, 7, 769355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokic, T.; Kezunovic, M. Predictive risk management for dynamic tree trimming scheduling for distribution networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 10, 4776–4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heluany, J.B.; Gkioulos, V. A review on digital twins for power generation and distribution. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2024, 23, 1171–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Xi, X.; Tang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, Z. Real-time scheduling of power grid digital twin tasks in cloud via deep reinforcement learning. J. Cloud Comput. 2024, 13, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandier, P.; Collet, C.; Miller, J.H.; Reynolds, P.E.; Zedaker, S.M. Designing forest vegetation management strategies based on the mechanisms and dynamics of crop tree competition by neighbouring vegetation. For. Int. J. For. Res. 2006, 79, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, S.; Rauf, M.; Ashraf, S.; Bin Md Ayob, S.; Ahmad Arfeen, Z. CART-ANOVA-based transfer learning approach for seven distinct tumor classification schemes with generalization capability. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Authors | Year | Key Contributions | Relevance and Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Faisal et al. [2] | 2025 | Reviews deep learning approaches for automated power line inspection, covering component detection, fault diagnosis, imaging modalities, and datasets. | Focuses broadly on inspection tasks where vegetation is treated as a secondary item and does not provide a framework for vegetation proximity detection and resilience in distribution lines. |

| 2 | Shen et al. [3] | 2024 | Reviews LiDAR-based methods using ML/DL for power line and pylon extraction | Focuses on power line extraction with limited discussion on vegetation proximity detection. |

| 3 | Mantach et al. [4] | 2022 | Explores the application of deep learning in high voltage engineering, focusing on power line inspection. | Offers valuable insights into DL applications but does not address tree proximity issues. |

| 4 | Singh et al. [5] | 2022 | Discusses AI techniques for tree detection using UAV and remote sensing, with a focus on deep learning models for object detection. | Emphasizes aerial image analysis without addressing proximity detection in the context of power lines. |

| 5 | Ibitoye et al. [6] | 2022 | Reviews ML techniques for fault detection in power grids, focusing on ensuring reliable power supply. | Focuses on ensuring reliable power supply. Limited discussion on vegetation management strategies using ML/DL. |

| 6 | Khodayar et al. [7] | 2021 | Comprehensive review of deep learning methodologies applied in power systems. | Provides foundational knowledge on DL in power systems without focusing on vegetation proximity detection. |

| 7 | Haroun et al. [8] | 2020 | Reviews satellite image techniques for vegetation encroachment detection, focusing on cost-effectiveness and extensive coverage. | Primarily focuses on satellite imagery techniques without analyzing ML/DL applications for dynamic environments. |

| 8 | Alimi et al. [9] | 2020 | Reviews ML techniques for power system security and stability. | Focuses on event classification in power systems. Does not address specific vegetation management. |

| Article Type | Publication Title | Frequency Count |

|---|---|---|

| Journal papers (92 papers) | Forests | 8 |

| Remote Sensing | 5 | |

| IEEE Access, Sustainable Cities and Society, Energies, IET Generation Transmission and Distribution, International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation | 3 | |

| Applied Energy, Utilities Policy, Electronics Switzerland, Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, Bulletin of Glaciological Research, Canadian Journal of Forest Research, Applied Sciences Switzerland, Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology, Ecology Letters, ASCE ASME Journal of Risk and Uncertainty in Engineering Systems Part A Civil Engineering, Giscience and Remote Sensing, Water Resources Management, Cryosphere, IEEE Sensors Journal, IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, Automation in Construction, International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering, International Journal Of Information Security, Forecasting, Sustainability Switzerland, Frontiers In Plant Science, Nature Communications, Molecular Ecology, Arboriculture And Urban Forestry, Croatian Journal Of Forest Engineering, Frontiers In Applied Mathematics And Statistics, Science, Science of The Total Environment, Scientific Reports, Sensors, Journal of Geophysical Research Biogeosciences, Journal Of Ecology, Climatic Change, Journal Of Cloud Computing, ISPRS International Journal Of Geo Information, Forestry, Annals of Botany, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Spatial Information Research, High Voltage, Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation, ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, Emerging Science Journal, CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems, IEEE Systems Journal, IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, Environmental Research Letters, Recent Advances in Computer Science and Communications, Forest Ecology and Management, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, International Journal of Energy Research, Ain Shams Engineering Journal, Wood Science and Technology, Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing | 1 | |

| Conference Paper (24 papers) | International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences (ISPRS) Archives | 3 |

| Proceedings of the International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction (ISARC) | 2 | |