Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainable Management of Forest Resources in a Socio-Cultural Upheaval of the Okapi Wildlife Reserve Landscape in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- the sociodemographic profiles of IPs in relation to their activities and indigenous forest conservation strategies;

- (2)

- their traditional ecological knowledge and customary resource governance;

- (3)

- their social perceptions of environmental change and their future aspirations;

- (4)

- the pathways of intergenerational knowledge transmission; and

- (5)

- the abundance of woody species within their habitats.

2. Materials and Methods

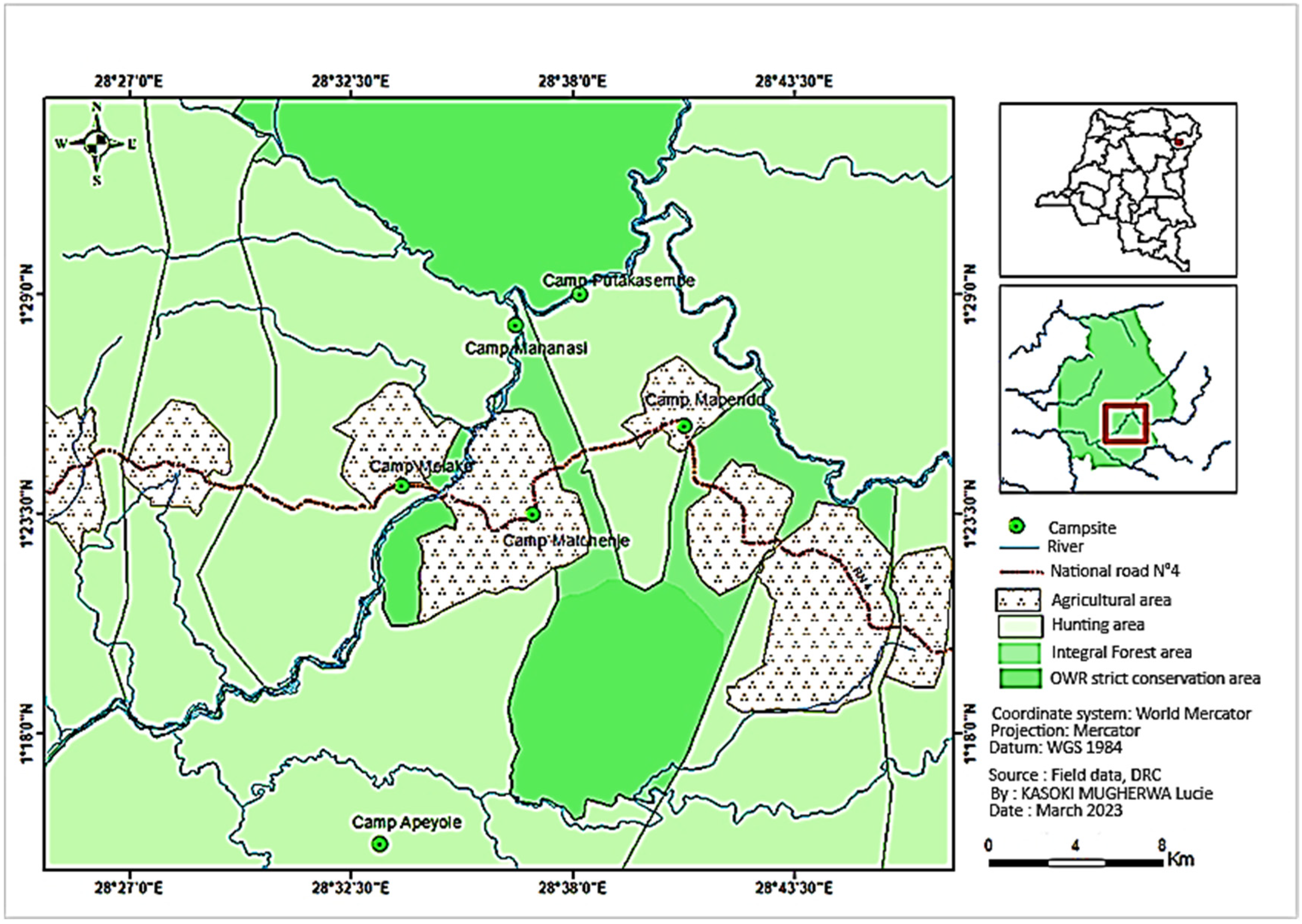

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Methodological Strategy

2.2.1. Secondary Data Collection

2.2.2. Primary Data Collection

- Sociodemographic dataSociodemographic data were obtained through comprehensive surveys conducted with 80 individuals (heads of households), representing the entire number of households enumerated across the six campsites. The distribution of respondents was as follows: Meiako (17), Mananasi (12), Matchenje (15), Apeyole (11), Mapendo (15), and Putakasembe (10). Collected variables included age, sex, marital status, educational level, household size, and duration of involvement in traditional activities.

- Data on the integration of indigenous knowledgeTwelve focus group discussions and semi-structured interviews were conducted with camp leaders and “elders” (both men and women), with an average of seven participants per camp. The themes addressed included perceived environmental changes, resource management practices, knowledge transmission, cultural taboos, and relations with Bantu populations.An inventory of empirical indicators related to soil fertility (presence of certain plants empirically used as bio-indicators to assess soil fertility; ants and earthworms) and the technical itineraries employed was compiled through these focus groups.

- Floristic inventory dataFor each camp, 500 m transects were established, along which three plots measuring 100 m × 25 m (plots 1, 3, and 5) were sampled, with orientation varying according to local geography (e.g., 180° at Meiako, 110° at Matchenje, and 68° at Mapendo). Species selection criteria were based on their usage, cultural significance, and species abundance, while also recording disturbance factors such as fire, land clearing, and exploitation.

2.2.3. Data Analysis

2.3. Ethics and Results Validation

- -

- Free, prior, and informed consent was obtained from each participant;

- -

- Results were returned to the community representatives for validation through participatory feedback;

- -

- No protected species were destroyed or collected during the floristic inventory.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

3.2. Economic Activities and Endogenous Resource Conservation Strategies

3.2.1. Traditional and Contemporary Activities

3.2.2. Technical Knowledge and Exploitation Tools

3.3. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Customary Resource Regulations

Traditional Taboos

- An ancestral normative system for sustainable managementThe Indigenous communities under study possess strict customary rules governing access to and use of natural resources. These traditional taboos constitute genuine ecological regulatory tools, deeply rooted in potent spiritual and social representations.

- -

- Prohibitions related to fauna: Certain animal species must not be hunted or consumed, particularly in specific circumstances such as pregnancy or breastfeeding. For example, the consumption of meat is forbidden for pregnant women up to 3–4 months postpartum to avoid potential adverse effects on the infant’s health.

- -

- Prohibitions related to flora: Species such as Monodora tenuifolia and M. angolensis may not be cut with a machete or hoe, under threat of invoking curses (e.g., tooth loss, skin diseases, unsuccessful hunting). Due to fear of mystical or spiritual repercussions, some species receive implicit customary protection.

- Ecological, social, and spiritual functions of taboosTraditional taboos fulfill several key functions (Table 4).

- Diversity and specificities of taboosNot all camps uniformly enforce these taboos. This variability may reflect cultural differences among lineages, clans, or indigenous tribes; differential influence from proximity to Bantu populations or the OWR administration; and cultural erosion in certain camps due to modernization or the weakening of traditional structures.

- Strategic interpretation for conservationThese systems of taboos demonstrate that IPs are not merely users of nature but traditional managers thereof; they possess empirical and spiritual knowledge that can complement modern conservation policies; and they can be genuine allies in the co-management of OWR ecosystems if their customary institutions are recognized and valorized.

3.4. Perceptions and Dynamics of Change

3.4.1. Access to Resources and Lifestyle Changes

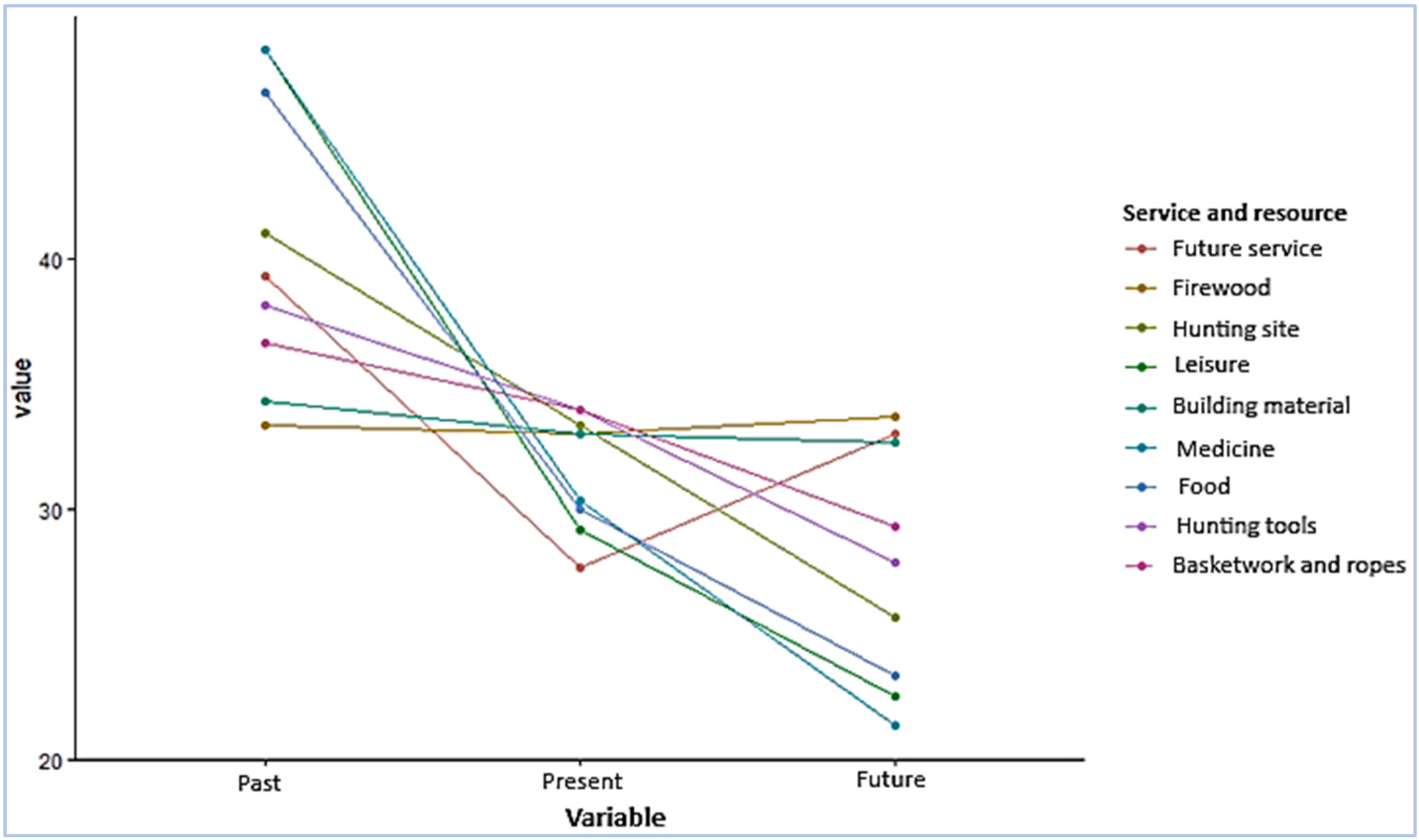

3.4.2. Importance Attributed to the Forest over Time

3.5. Social Perceptions and Future Projections

3.5.1. Evolution of Living Conditions

3.5.2. Perceptions of Resource Availability

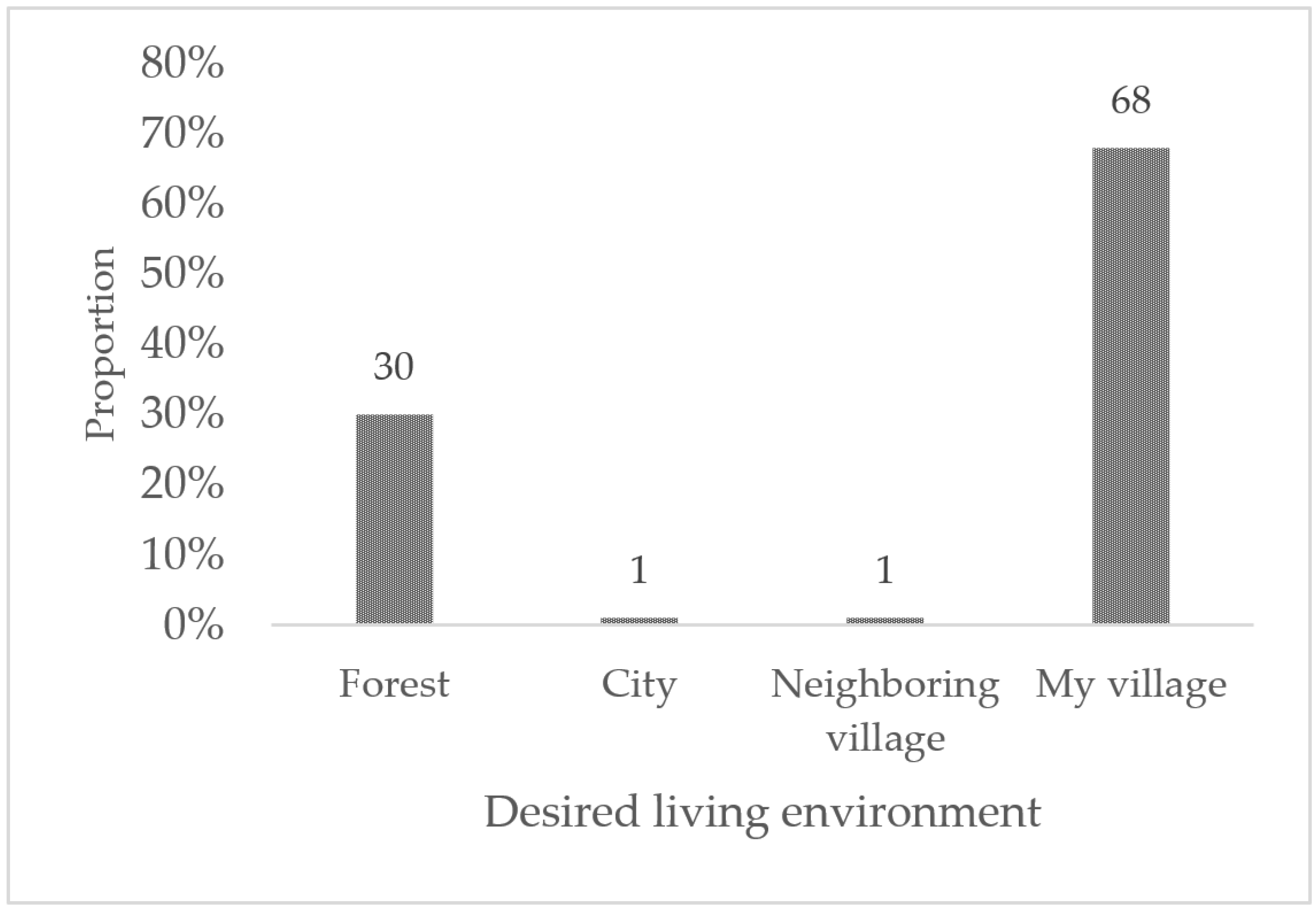

3.5.3. Future Habitat Preferences

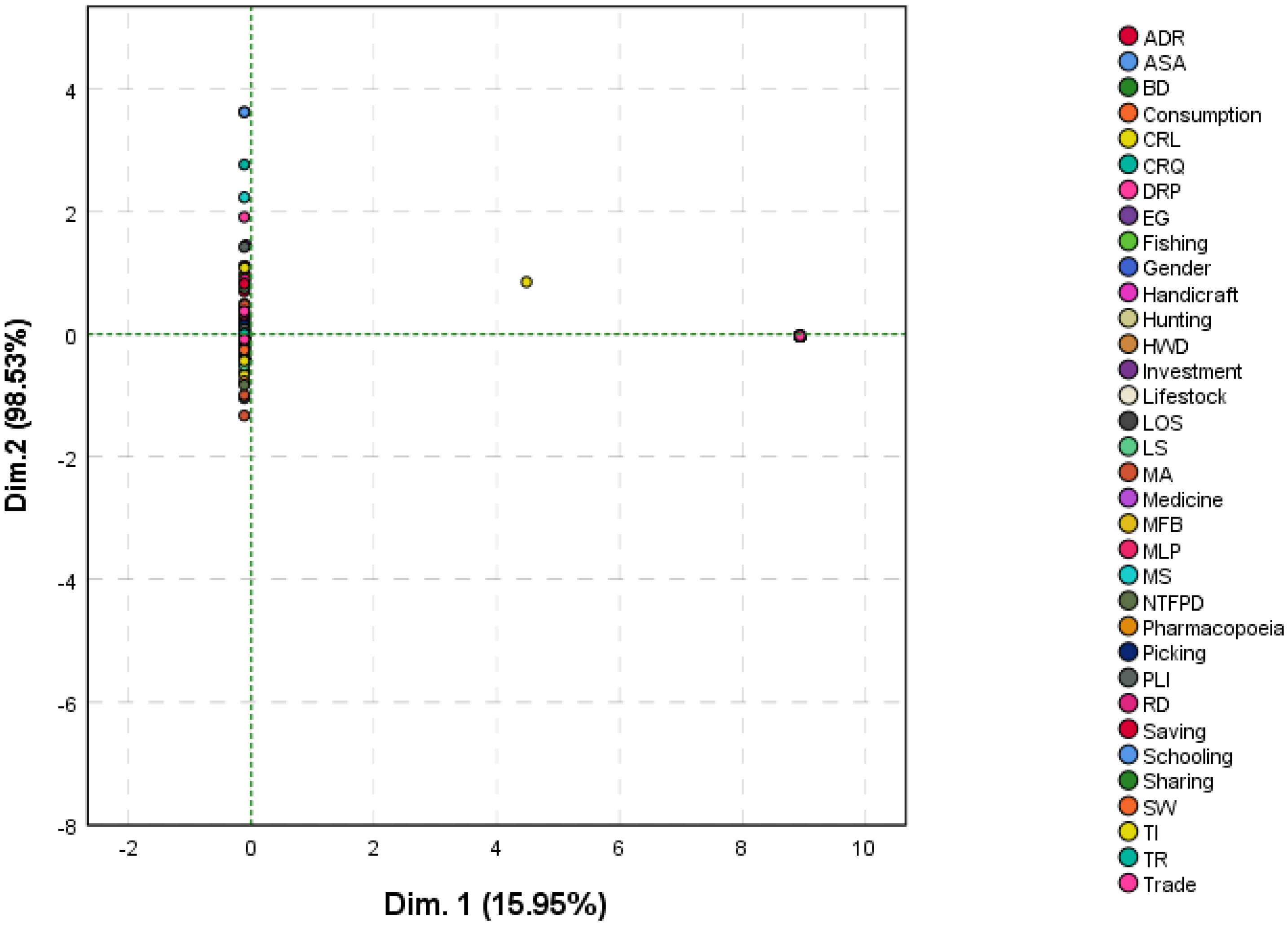

3.6. Association Between Socio-Demographic, Livelihood, and Perceptual Variables

3.7. Agroecological Knowledge and Practices

3.7.1. Indicators of Soil Fertility

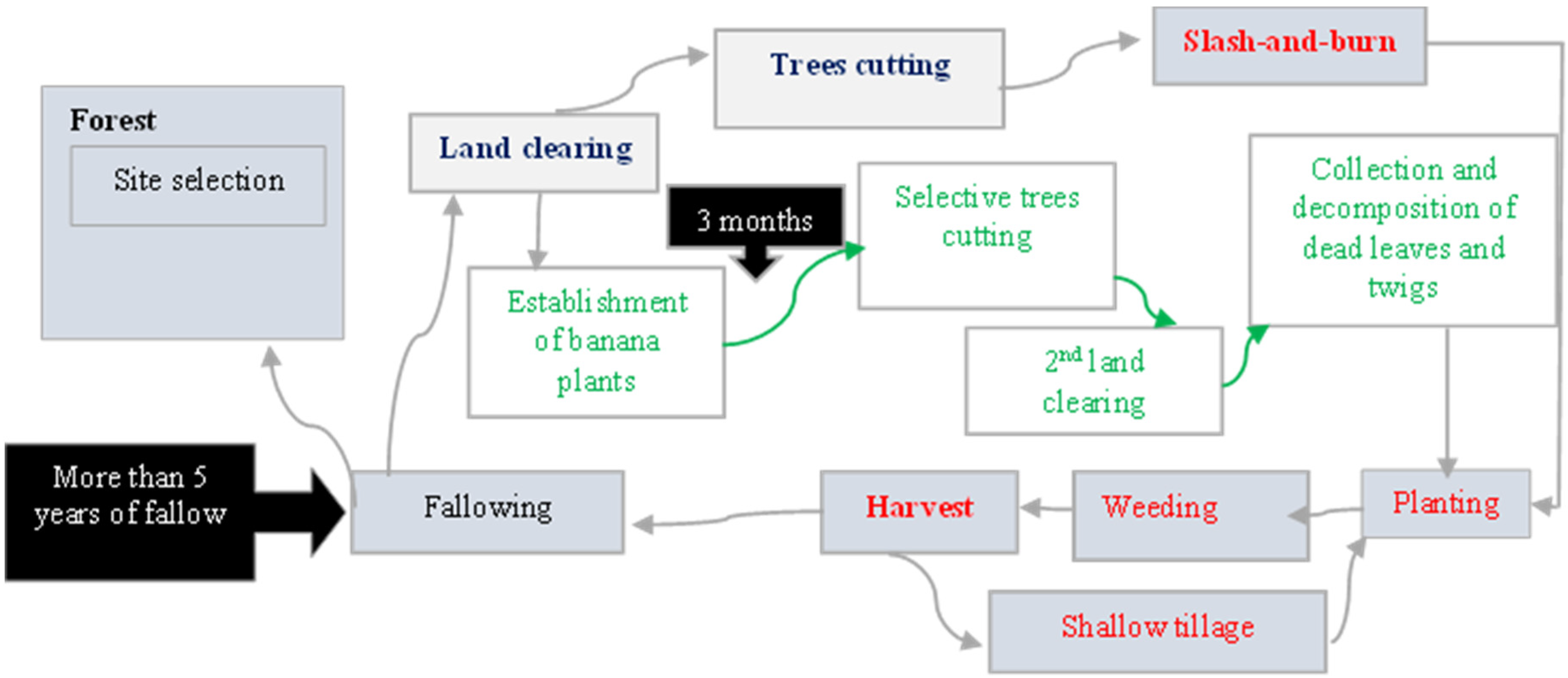

3.7.2. Technical Pathways

- -

- Slash-and-burn cultivation, an ancestral and more widespread practice;

- -

- Non-burn clearing, a more recent and sustainable method developed through symbiotic interaction with Bantu populations.

3.7.3. Conservation of Useful Species

3.8. Transmission of Endogenous Knowledge

3.9. Plant Abundance

3.9.1. Forest Camps

- -

- The indigenous peoples do not exploit resources randomly; differences in abundance can be explained by the presence of traditional taboos, the utility value of species, or ecological availability.

- -

- The case of Mananasi demonstrates that resource use can remain compatible with high biodiversity, especially when governed by sustainable harvesting practices.

- -

- Conversely, Putakasembe may represent a critical area requiring ecological restoration.

3.9.2. Campsites in Bantu Villages

- Statistical analysis (ANOVA and Ranking)

4. Discussion

4.1. Sociodemographic and Cultural Characteristics of Indigenous Peoples (IPs)

4.2. Endogenous and Ancestral Strategies for Forest Conservation and Sustainable Biodiversity Management

4.2.1. Traditional Prohibitions and Conservation

4.2.2. Adaptation to Current Sociocultural Disruptions

4.2.3. Risks Linked to Modernization of Certain Current Tools

4.2.4. Social Perceptions and Dynamics of Change

4.2.5. Adaptative Agroecological Knowledge and Practices

4.2.6. Implications of the Association Between Socio-Demographic, Livelihood, and Perceptual Variables

4.3. Floristic Diversity: An Indicator of Differential Pressures

4.4. Intergenerational Transmission of Knowledge and Skills

5. Recommendations

- -

- Strengthen mechanisms for the recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ land and resource rights: Secure access to land and natural resources is a fundamental prerequisite for the sustainability of traditional practices.

- -

- Support the conservation of endogenous knowledge: Programs aimed at documenting, valorizing, and transmitting agroecological and cultural knowledge across generations should be actively encouraged.

- -

- Promote ecologically sustainable livelihood alternatives: Supporting livelihood diversification, particularly through agroforestry, climate-resilient subsistence crops, and local crafts, would enhance the food and economic security of IPs.

- -

- Integrate IPs into decision-making processes: Their active participation in natural resource governance and conservation initiatives (such as participatory management of the OWR) is essential to ensure equity and the effectiveness of environmental policies.

- -

- Raise awareness about the impacts of modern tools: Tailored environmental education programs should be implemented to mitigate the adverse effects of recently introduced practices (e.g., nylon fishing nets, unregulated extensive agriculture).

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Gender | EG | LS | PLI | HWD | BD | CRL | CRQ | TR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA | 97.509, df = 14, p-value = 1.421 × 10−14 | 81, df = 7, p-value = 8.612 × 10−15 | 112.28, df = 21, p-value = 1.826 × 10−14 | 109.54, df = 28, p-value = 1.363 × 10−11 | |||||

| ASA | 81.016, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 82.624, df = 6, p-value = 1.025 × 10−15 | 83.373, df = 8, p-value = 1.022 × 10−14 | |||||

| CRQ | 84.814, df = 6, p-value = 3.608 × 10−16 | 81, df = 3, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 96.954, df = 9, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 127.47, df = 12, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 83.662, df = 6, p-value = 6.249 × 10−16 | 84.287, df = 6, p-value = 4.639 × 10−16 | 50.373, df = 6, p-value = 3.957 × 10−9 | ||

| Hunting | 88.056, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 89.851, df = 6, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 91.104, df = 8, p-value = 2.776 × 10−16 | 81.35, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81.054, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 40.169, df = 4, p-value = 3.994 × 10−8 | ||

| Picking | 87.943, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 85.63, df = 6, p-value = 2.444 × 10−16 | 85.04, df = 8, p-value = 4.704 × 10−15 | 82.074, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81.051, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 45.334, df = 4, p-value = 3.388 × 10−9 | ||

| Fishing | 81.15, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 83.842, df = 6, p-value = 5.734 × 10−16 | 95.008, df = 8, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81.224, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 85.774, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 46.045, df = 4, p-value = 2.41 × 10−9 | ||

| Livestock | 82.535, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 82.879, df = 6, p-value = 9.074 × 10−16 | 82, df = 8, p-value = 1.933× 10−14 | 81.005, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 82.314, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 41.365, df = 4, p-value = 2.258 × 10−8 | ||

| MLP | 96.242, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 86.658, df = 6, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 83.144, df = 8, p-value = 1.136× 10−14 | 82.295, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 83.068, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 40.794, df = 4, p-value = 2.965 × 10−8 | ||

| MFB | 85.406, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81.662, df = 6, p-value = 1.62 × 10−15 | 87.686, df = 8, p-value = 1.37 × 10−15 | 81.294, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81.039, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 42.077, df = 4, p-value = 1.608 × 10−8 | ||

| CRL | 50.129, df = 4, p-value = 3.394 × 10−10 | 39.994, df = 2, p-value = 2.068 × 10−9 | 42.961, df = 6, p-value = 1.187 × 10−7 | 42.528, df = 8, p-value = 1.078 × 10−6 | 49.728, df = 4, p-value = 4.115 × 10−10 | 45.972, df = 4, p-value = 2.496 × 10−9 | 162, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | ||

| Pharma | 84.315, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 82.371, df = 6, p-value = 1.156 × 10−15 | 81.521, df = 8, p-value = 2.414 × 10−14 | 93.992, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 96.411, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 50.091, df = 4, p-value = 3.457 × 10−10 | 81.563, df = 6, p-value = 1.698 × 10−15 | |

| LS | 88.556, df = 6, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 3, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | - | 84.625, df = 12, p-value = 5.373 × 10−13 | 85.389, df = 6, p-value = 2.742 × 10−16 | 85.314, df = 6, p-value = 2.842 × 10−16 | 42.961, df = 6, p-value = 1.187× 10−7 | 96.954, df = 9, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 3, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 |

| PLI | 83.988, df = 8, p-value = 7.672 × 10−15 | 81, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 84.625, df = 12, p-value = 5.373 × 10−13 | 324, df = 16, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 83.297, df = 8, p-value = 1.058 × 10−14 | 85.232, df = 8, p-value = 4.3 × 10−15 | 42.528, df = 8, p-value = 1.078 × 10−6 | 127.47, df = 12, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 |

| NTFPD | 82.687, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 83.842, df = 6, p-value = 5.734 × 10−16 | 84.18, df = 8, p-value = 7.017 × 10−15 | 121.17, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 110.4, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 58.269, df = 4, p-value = 6.7e × 10−12 | 83.673, df = 6, p-value = 6.216 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 |

| HWD | 81.005, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 85.389, df = 6, p-value = 2.742 × 10−16 | 83.297, df = 8, p-value = 1.058 × 10−14 | - | 118.68, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 49.728, df = 4, p-value = 4.115 × 10−10 | 83.662, df = 6, p-value = 6.249 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 |

| BD | 81.727, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 85.314, df = 6, p-value = 2.842 × 10−16 | 85.232, df = 8, p-value = 4.3 × 10−15 | 118.68, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 162, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 45.972, df = 4, p-value = 2.496× 10−9 | 84.287, df = 6, p-value = 4.639 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 |

| RD | 82.532, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 86.178, df = 6, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 83.373, df = 8, p-value = 1.022× 10−14 | 91.647, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 109.23, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 50.867, df = 4, p-value = 2.379 × 10−10 | 81.662, df = 6, p-value = 1.62 × 10−15 | |

| TI | 81.379, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 83.288, df = 6, p-value = 7.467 × 10−16 | 98.568, df = 8, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 117.12, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 102.5, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 41.98, df = 4, p-value = 1.684 × 10−8 | 90.977, df = 6, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | |

| SW | 81.048, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81, df = 2, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 81.771, df = 6, p-value = 1.538 × 10−15 | 86.708, df = 8, p-value = 2.163 × 10−15 | 101.66, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−1 | 104.46, df = 4, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | 46.55, df = 4, p-value = 1.892 × 10−9 | 83.978, df = 6, p-value = 5.375 × 10−16 |

References

- Dalimier, P.; Fayolle, A.; Monticelli, D. Biodiversité et Services Écosystémiques des Forêts du Bassin du Congo: Enjeux, Menaces et Perspectives; Éditions de l’AFD: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- De Wasseige, C.; Tadoum, M.; Eba’a Atyi, R.; Doumenge, C. (Eds.) Les Forêts du Bassin du Congo: Forêts et Changements Climatiques; Office des Publications de l’Union Européenne: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Wasseige, C.; Flynn, J.; Louppe, D.; Hiol Hiol, F.; Mayaux, P. (Eds.) Les Forêts du Bassin du Congo: État des Forêts 2013; Office des Publications de l’Union Européenne/FAO/OIBT/COMIFAC: Yaoundé, Cameroun, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Megevand, C.; Mosnier, A.; Hourticq, J.; Sanders, K.; Doetinchem, N.; Streck, C. Dynamiques de Déforestation dans le Bassin du Congo: Réconcilier Croissance Économique et Protection de la Forêt; Banque Mondiale: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- World Bank. République Démocratique du Congo: Cadre Stratégique pour la Préparation d’un Programme de Développement des Pygmées (Rapport n° 51108-ZR); World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kipalu, P.; Kiyulu, J.; Uwimana, A. Les Peuples Autochtones et les Forêts: Vers une Reconnaissance Légale en RDC; RFUK/Forest Peoples Programme: Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Initiative Interreligieuse pour les Forêts Tropicales. Peuples Autochtones et Forêts: Allié.e.s dans la Conservation Mondiale; UNEP: Oslo, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bahuchet, S.; McKey, D.; de Garine, I. (Eds.) Les Peuples des Forêts Tropicales Humides d’Afrique: Anthropologie, Écologie et Histoire; CNRS Éditions: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chianese, F.; Goldammer, J.G.; Rinaudo, T. Indigenous Peoples and Forest Biodiversity: A Study of Indigenous Practices and Biodiversity Conservation; UICN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mandjo, D.L.; Kamdem, C.G.; Nana, J. Savoirs traditionnels et conservation des écosystèmes en Afrique centrale. Rev. Géogr. Cameroun 2015, 2, 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bireshwar, B. Biodiversity hotspots: The role of indigenous communities in preservation. IPE J. Manag. 2024, 14, 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Mbai, F. Changement climatique, peuples autochtones et résilience en Afrique centrale. Rev. Int. Sci. Soc. Hum. 2020, 33, 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- MECNET. Peuples Autochtones et Gestion des Ressources Naturelles en Afrique Centrale; MECNET Africa: Nairobi, Kenya, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Musavandalo, G. Vulnérabilité socio-écologique et déterritorialisation des pygmées en RDC. Cah. d’Anthropol. 2021, 49, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Forêts et Moyens de Subsistance des Peuples Autochtones en Afrique; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Forêts et Moyens de Subsistance des Peuples Autochtones en Afrique, 2nd ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kipalu, P.; Ndinga, A.; Sanz, N. Les Peuples Autochtones de la République Démocratique du Congo: Entre Marginalisation et Reconnaissance; Forest Peoples Programme: Moreton-in-Marsh, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.forestpeoples.org (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Oviedo, G.; Maffi, L. Indigenous and Traditional Peoples of the World and Ecoregion Conservation: An Integrated Approach to Conserving the World’s Biological and Cultural Diversity; WWF International and Terralingua: Gland, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. État des Forêts du Monde 2007; Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’Alimentation et l’Agriculture: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Les Forêts et l’Agriculture: Défis et Opportunités à l’Horizon 2050; Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’Alimentation et l’Agriculture: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sheil, D.; Boissière, M. Local people may be the best allies in conservation. Nature 2006, 440, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse Kifle, E.; Noulèkoun, F.; Son, Y.; Khamzina, A. Woody species diversity, structural composition, and human use of church forests in central Ethiopia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 506, 119991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonds Social-RDC. Plan pour les Peuples Autochtones Pygmées (PPAP): Projet de Filets Sociaux Productifs; République Démocratique du Congo: Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Plan d’Aménagement et de Gestion de la RFO. Réserve de Faune à Okapis—Plan de gestion 2010–2020; ICCN/WCS: Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sheil, D.; Boissière, M.; van Heist, M.; de Jong, W.; Cunliffe, R.; Wan, M.; Padmanaba, M.; Liswanti, N.; Basuki, I.; Evans, K.; et al. Researching Local Perspectives on Biodiversity in Tropical Landscapes: Lessons from Ten Case Studies. In Taking Stock of Nature: Participatory Biodiversity Assessment for Policy, Planning and Practice; Lawrence, A., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 113–141. [Google Scholar]

- Fleury, M.; Schmook, B.; Tschakert, P. Youth agency in sustaining Indigenous knowledge. Geoforum 2022, 132, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, W.H.; Büscher, B.; Schoon, M.; Brockington, D.; Hayes, T.; Kull, C.A.; Mccarthy, J.; Shrestha, K. From hope to crisis and back again? A critical history of the global CBNRM narrative. Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colfer, C.J.P.; Peluso, N.L.; Chung, C.S. Beyond Slash and Burn: Building on Indigenous Management of Borneo’s Tropical Rainforests; The New York Botanical Garden Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-García, V.; Gueze, M.; Luz, A.C.; Paneque-Gálvez, J.; Macía, M.J.; Orta-Martínez, M.; Pino, J.; Rubio-Campillo, X. Evidence of traditional knowledge loss among a contemporary Indigenous society. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2013, 34, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Sacred Ecology, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Garnett, S.T.; Burgess, N.D.; Fa, J.E.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Molnár, Z.; Robinson, C.J.; Watson, J.E.M.; Zander, K.K.; Austin, B.; Brondizio, E.S.; et al. A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, D.A. Cultural and Spiritual Values of Biodiversity; UNEP/Intermediate Technology Publications: Nairobi, Kenya, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, B. Temps du Sang, Temps des Cendres; Maison des Sciences de l’Homme: Paris, France, 1985; Available online: https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/doc34-08/19886 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Lévi-Strauss, C. Paroles Données; Plon: Paris, France, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, P.B.; Springer, J. The Role of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in Natural Resource Governance; IUCN: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Convention sur la Diversité Biologique (CDB). Plan Stratégique 2011–2020 pour la Diversité Biologique; Secrétariat de la CDB: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.A. Agroecology: The Science of Sustainable Agriculture; WestviewPress: Boulder, CO, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P.L. Women and the Plant World: Gender Relations in Biodiversity Management and Conservation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Naughton-Treves, L.; Holland, M.B.; Brandon, K. The role of protected areas in conserving biodiversity and sustaining local livelihoods. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 219–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, N.M.; Coolsaet, B.; Sterling, E.J.; Loveridge, R.; Schreiber, H. The role of Indigenous peoples and local communities in effective and equitable conservation. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombad, C.; Tchatchoua, B.; Tadjuidje, M. Perceptions locales des changements environnementaux dans les communautés forestières du Cameroun. Forêt Polit. 2021, 14, 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Le Tourneau, F.-M.; Droulers, M.; Bursztyn, M. La Territorialisation de l’Amazonie; IRD Éditions: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F. Sacred Ecology, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-García, V.; García-del-Amo, D.; Benyei, P.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Gravani, K.; Junqueira, A.B.; Labeyrie, V.; Li, X.; Matias, D.M.; McAlvay, A.; et al. A collaborative approach to bring insights from local communities into global assessments. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colding, J.; Folke, C. Social taboos: “Invisible” systems of local resource management and biological conservation. Ecol. Appl. 2001, 11, 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarter, J.; Gavin, M.C. Local perceptions of changes in traditional ecological knowledge: A case study from Malekula Island, Vanuatu. Ambio 2014, 43, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengö, M.; Brondizio, E.S.; Elmqvist, T.; Malmer, P.; Spierenburg, M. Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: The multiple evidence base approach. Ambio 2014, 43, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Reyes-García, V.; Olsson, P.; Montes, C. Traditional ecological knowledge and community resilience to environmental extremes. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1327–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Adams, B.; Berkes, F.; De Athayde, S.F.; Dudley, N.; Hunn, E.; Maffi, L.; Milton, K.; Rapport, D.; Robbins, P.; et al. The intersections of biological diversity and cultural diversity: Towards integration. Conserv. Soc. 2009, 7, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Speranza, I.C. IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Abernethy, K.A.; Coad, L.; Taylor, G.; Lee, M.E.; Maisels, F. Extent and ecological consequences of hunting in Central African rainforests in the twenty-first century. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20120303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vliet, N.; Milner-Gulland, E.J.; Bousquet, F.; Saqalli, M.; Nasi, R. Effect of small-scale heterogeneity of prey and hunter distributions on the sustainability of bushmeat hunting. Conserv. Biol. 2012, 24, 1329–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, S.L.; Fuller, R.A.; Brooks, T.M.; Watson, J.E. Biodiversity: The ravages of guns, nets and bulldozers. Nature 2016, 536, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Perrin, N. Climate adaptation, local institutions, and rural livelihoods. In Adapting to Climate Change: Thresholds, Values, Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 350–367. [Google Scholar]

- Cinner, J.E.; McClanahan, T.R.; MacNeil, M.A.; Graham, N.A.; Daw, T.M.; Mukminin, A.; Feary, D.A.; Rabearisoa, A.L.; Wamukota, A.; Jiddawi, N.; et al. Co-management of coral reef social-ecological systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 5219–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galaty, J.G. Being “Maasai”; being “People-of-Cattle”: Ethnic shifters in East Africa. Am. Ethnol. 1982, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) Programme: 20th Anniversary Statement; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Classification | Number | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Women | 34 | 42.50 |

| Men | 46 | 57.50 | |

| Campsites | Putakasembe | 10 | 12.50 |

| Apeyole | 11 | 13.75 | |

| Mananasi | 12 | 15.00 | |

| Mapendo | 15 | 18.75 | |

| Matchenje | 15 | 18.75 | |

| Meiako | 17 | 21.25 | |

| Level of study | Illiterate | 36 | 45 |

| Primary | 42 | 52.50 | |

| High school | 2 | 2.50 | |

| Age | 18–25 years | 24 | 28.75 |

| 25–30 years | 11 | 13.75 | |

| 30–35 years | 10 | 12.50 | |

| 35–40 years | 11 | 13.75 | |

| 40–45 years | 5 | 7.50 | |

| 40–45 years | 1 | 1.25 | |

| 45–50 years | 5 | 6.25 | |

| >50 years | 13 | 16.25 | |

| Marital status | Single | 8 | 10 |

| Married | 70 | 87.50 | |

| Widow | 2 | 2.50 |

| Traditional Activities | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village | Campsite | Hunting | Picking | Fishing | Agriculture | Handicraft | Manpower for Bantus | Honey Harvesting |

| Babama | Mapendo | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| Putakasembe | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | |

| Bapukeli | Matchenje | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| Apeyole | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | |

| Epulu | Meiako | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| Mananasi | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | |

| Current activities | ||||||||

| Babama | Mapendo | + | + | + | ○ | + | + | + |

| Putakasembe | + | + | + | ○ | + | + | + | |

| Bapukeli | Matchenje | + | + | + | ○ | + | + | + |

| Apeyole | + | + | ○ | ○ | + | + | + | |

| Epulu | Meiako | + | + | + | ○ | + | + | + |

| Mananasi | + | + | + | ○ | + | + | + | |

| Traditional Used Tools | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village | Campsite | Traditional Net | Nylon Net | Arrow | Arc | Fishpot | Trap | Dog | Hook | Gun |

| Babama | Mapendo | + | − | + | + | + | ○ | + | + | − |

| Putakasembe | + | − | + | + | + | ○ | + | + | − | |

| Bapukeli | Matchenje | + | − | + | + | + | ○ | + | + | − |

| Apeyole | + | − | + | + | + | ○ | + | + | − | |

| Epulu | Meiako | + | − | + | + | + | ○ | + | + | − |

| Mananasi | + | − | + | + | + | ○ | + | + | − | |

| Current used tools | ||||||||||

| Babama | Mapendo | + | + | + | + | ○ | ○ | + | + | ○ |

| Putakasembe | + | + | + | + | + | ○ | + | + | ○ | |

| Bapukeli | Matchenje | + | ○ | + | + | ○ | ○ | + | + | ○ |

| Apeyole | + | ○ | + | + | ○ | ○ | + | + | ○ | |

| Epulu | Meiako | + | + | + | + | ○ | ○ | + | + | ○ |

| Mananasi | + | + | + | + | + | ○ | + | + | ○ | |

| Function | Details |

|---|---|

| Ecological | They contribute to the conservation of vulnerable species (animal and plant), often without a formal conservation framework. |

| Social | They structure social roles and life cycles (e.g., pregnant women), strengthening community cohesion. |

| Spiritual | Mystical sanctions ensure compliance with rules even in the absence of material oversight, thereby reinforcing a symbolic form of environmental control. |

| Services and Resources | p-Value |

|---|---|

| Food | 0.0089 *** |

| Medicine | 0.0015 *** |

| Building material | 0.1976 Ns |

| Firewood | 0.2548 Ns |

| Basketwork and ropes | 0.0085 ** |

| Hunting tools | 0.0145 * |

| Hunting site | 0.0132 * |

| Leisure | 0.0058 *** |

| Dimension | Cronbach’s Alpha | Total (Eigenvalue) | Inertia | % of Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.000 | 33.502 | 0.985 | 98.534 |

| 2 | 0.840 | 5.422 | 0.159 | 15.948 |

| Total | 38.924 | 1.145 | ||

| Means | 0.977 a | 19.462 | 0.572 | 57.241 |

| Indicators | Justifications Provided by IPs |

|---|---|

| Presence of reeds (Echinochloa pyramidalis (Lam.) Hitchc. et Chase) | Reed leaves decompose rapidly, contributing to a rich organic litter layer. Drawing from experiential knowledge, local communities have noted that these areas are particularly conducive to high yields of cassava and groundnut crops. |

| Presence of ants and earthworms | Irrespective of crop type, the presence of ants and earthworms is consistently linked to enhanced agricultural productivity. |

| Unburned field | Although emphasized by only a small proportion of the population (≤1/10), unburned lands remain fertile over extended periods and consistently provide good long-term agricultural yields |

| Presence of certain tree species | Species such as Floribunda olive L., Erythrophleum suaveolens (Guill. et Perr.) Brenan, Strombosa grandifolia Hook.f, Cassia occidentalis L., Chromolaena odorata (L.) R.M.King & H. Rob., Dioscorea bulbifera L., Massularia acuminata (G. Don) Bullock ex Hoyle, Ricinodendron heudelotii (Baill.) Pierre ex Heckel, and Irvingia gabonensis (Aubry-LeComte ex O’Rorke) Baill. are empirically used as bio-indicators to assess soil fertility. |

| Absence of stones in the ground | The greater the abundance of stones in the soil, the more difficult it becomes for roots to grow and nourish plants. Cultivation of cassava and other tuber crops must take this factor into account, as these crops produce tubers in the soil that require loose and well-aerated substrates. |

| Species | Reason |

|---|---|

| Allablackia floribunda Oliv. | Fruits highly consumed by wildlife |

| Strombosia grandifolia Hook.f Myriathus preussii Engl. Aida micrantha (K. Schum.) F. White | Leaves grazed by the Okapi |

| Anonidium mannii (Oliv.) Engl. et Diels | Fruit highly consumed by monkeys |

| Afzelia bella Harms | Bee niche (source of honey) |

| Ricinodendron heudolotii | Fruit consumed by antelopes and caterpillar niche (consumed by Indigenous Peoples). |

| Campsites | Putakasembe | Apeyole | Mananasi | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Mean + SD | Group | Mean + SD | Group | Mean + SD | Group |

| Afromomum alboviolaceum (Ridl.) K. Schum | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 0.00 | g | 2.67 ± 1.45 | fg |

| Aidia micrata | 1.00 ± 0.99 | g | 8.00 ± 1.15 | efg | 16.33 ± 7.85 | defg |

| Annonidium manii | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 1.00 ± 0.57 | g | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g |

| Canarium schweinfurthii Engl. | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 0.00 | g | 1.00 ± 0.99 | g |

| Cola acuminata (P.Beauv.) Schott & Endl. | 1.67 ± 1.66 | g | 3.00 ± 1.15 | fg | 1.33 ± 1.33 | g |

| Combretum marginatum G. Don | 1.00 ± 0.99 | g | 7.00 ± 1.15 | efg | 7.33 ± 3.93 | efg |

| Cynometra alexandri C.H.Wright | 3.00 ± 3.00 | fg | 10.33 ± 1.20 | defg | 37.67 ± 6.74 | cdefg |

| Desplatsia dewevrei (De Wild. & T. Durand) Burret | 0.67 ± 0.66 | g | 4.00 ± 1.73 | fg | 14.33 ± 4.84 | defg |

| Diospyros bipindesis Gürke | 0.67 ± 0.66 | g | 15 ± 2.00 | defg | 12.67 ± 6.76 | defg |

| Discorea sp. 1 | 0.33 ± 0.58 | g | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 8.33 ± 2.90 | efg |

| Discorea sp. 2 | 0.00 | g | 0.00 | g | 0.00 | g |

| Dryptes gossweileri S.Moore | 1.67 ± 1.66 | g | 26.33 ± 4.63 | cdefg | 57.33 ± 12.41 | cd |

| Eremospatha haullevilleana De Wild. | 0.00 | g | 0.00 | g | 5.67 ± 5.17 | efg |

| Erythrina mildibraedii Harms | 1.33 ± 1.33 | g | 27.33 ± 3.93 | cdefg | 73.67 ± 21.52 | bc |

| Garcinia kola Heckel | 0.00 | g | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 1.00 ± 0.00 | g |

| Gilbertiodendron dewevrei (De Wild.) J.Léonard | 0.00 | g | 160.00 ± 0.00 | a | 0.00 | g |

| Isolana congolana (De Wild. et Th. Dur.) Engl. et Diels | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 11.00 ± 3.05 | defg | 53.33 ± 4.25 | cde |

| Julbernadia seretii (De Wild.) Troupin | 0.00 | g | 12.67 ± 1.85 | defg | 0.00 | g |

| Lendolphia owariensis P. Beauv | 0.00 | g | 4.00 ± 0.99 | fg | 0.00 | g |

| Loeseneriella africana (Willd.) N.Hallé | 0.00 | g | 3.33 ± 1.76 | fg | 4.00 ± 1.15 | Fg |

| Macaraga spinosa Müll.Arg | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 4.00 ± 0.99 | Fg |

| Manniophyton fulvum Müll. Arg. | 5.00 ± 4.99 | efg | 12.33 ± 0.66 | defg | 26.67 ± 3.71 | cdefg |

| Megaphrynium macrostachyum (Benth. et Hook. f.) Milne-Redh. | 0.00 | g | 2.67 ± 1.66 | fg | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g |

| Plukenetia conophora Müll.Arg. | 0.00 | g | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 3.00 ± 3.00 | fg |

| Pyrenacantha puberula Engl. | 0.00 | g | 0.67 ± 0.66 | g | 0.67 ± 0.33 | g |

| Rourea obliquifoliolata (Gilg) G. Schellenb | 0.67 ± 0.66 | g | 6.67 ± 0.66 | efg | 4.67 ± 2.40 | fg |

| Scaphopetalum dewevrei De Wild. et T. Durand | 53.33 ± 53.33 | cde | 34.33 ± 5.45 | cdefg | 140.00 ± 19.99 | a |

| Dominant Species | Putakasembe | Apeyole | Mananasi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean + SD | |||

| G. dewevrei | 0.00 | 160.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 |

| S. dewevrei | 53.33 ± 53.33 | 34.33 ± 5.45 | 140.00 ± 19.99 |

| E. mildibraedii | 1.33 ± 1.33 | 27.33 ± 3.93 | 73.67 ± 21.52 |

| D. spinodentata | 1.67 ± 1.66 | 26.33 ± 4.63 | 57.33 ± 12.41 |

| Campsite | Mapendo | Matchenje | Meiako | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Mean + SD | Group | Mean + SD | Group | Mean + SD | Group |

| Afromomum alboviolaceum | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 1.00 ± 0.57 | g | 7.67 ± 2.96 | efg |

| Aidia micrata | 2.00 ± 1.15 | g | 3.67 ± 2.73 | fg | 14 ± 9.53 | defg |

| Annonidium manii | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 2.00 ± 0.99 | g | 1.33 ± 0.66 | g |

| Canarium schweinfurthii | 1.00 ± 0.57 | g | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 0.67 ± 0.33 | g |

| Cola acuminata | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 3.00 ± 2.51 | fg | 2.67 ± 1.45 | fg |

| Combretum marginatum | 0.67 ± 0.66 | g | 1.00 ± 0.57 | g | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g |

| Cynometra alexandri | 1.67 ± 0.88 | g | 0.00 | g | 1.67 ± 1.2 | g |

| Desplatsia dewevrei | 0.00 | g | 0.00 | g | 1.67 ± 1.66 | g |

| Diospyrose bipindesis | 0.00 | g | 1.67 ± 0.88 | g | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g |

| Discorea sp. 1 | 2.67 ± 1.45 | fg | 21.67 ± 14.40 | defg | 5.67 ± 4.69 | efg |

| Discorea sp. 2 | 0.67 ± 0.66 | g | 0.00 | g | 1.33 ± 0.88 | g |

| Dryptes gossweileri | 1.00 ± 0.57 | g | 4.00 ± 2.08 | fg | 3.00 ± 0.99 | fg |

| Eremospatha haullevilleana | 1.33 ± 0.88 | g | 7.67 ± 6.66 | efg | 0.67 ± 0.66 | g |

| Erythrina mildibraedii | 1.33 ± 1.33 | g | 0.67 ± 0.33 | g | 2.33 ± 1.85 | fg |

| Garcinia kola | 0.00 | g | 0.00 | g | 0.00 | g |

| Gilbertiodendron dewevrei | 16.67 ± 16.66 | defg | 13.33 ± 6.69 | defg | 50 ± 28.57 | cdef |

| Isolana congolana | 0.00 | g | 0.00 | g | 3.67 ± 2.16 | fg |

| Julbernadia seretii | 1.33 ± 0.88 | g | 1.00 ± 0.99 | g | 12.67 ± 4.67 | defg |

| Lendolphia owariensis | 0.00 | g | 1 ± 0.57 | g | 2.67 ± 0.33 | fg |

| Loeseneriella africana | 0.67 ± 0.33 | g | 0.00 | g | 2.33 ± 0.66 | fg |

| Macaraga spinosa | 0.00 | g | 1 ± 0.57 | g | 1.00 ± 0.55 | g |

| Manniophyton fulvum | 2.33 ± 1.45 | fg | 10.33 ± 5.45 | defg | 3.33 ± 0.88 | fg |

| Megaphrynium macrostachyum | 34.33 ± 32.34 | cdefg | 113.3 ± 32.82 | ab | 34.67 ± 32.67 | cdefg |

| Plukenetiaconophora | 0.00 | g | 0.00 | g | 1.00 ± 0.99 | g |

| Pyrenacantha puberula | 1.00 ± 0.57 | g | 1.67 ± 1.66 | g | 0.67 ± 0.33 | g |

| Rourea obliquifoliolata | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 0.33 ± 0.33 | g | 1.33 ± 0.33 | g |

| Scaphopetalum dewevrei | 3.00 ± 1.52 | fg | 13.33 ± 7.88 | defg | 9.00 ± 1.99 | defg |

| Campsite | Dominant Species | Abundance (Ind./Plot) | Species Richness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meiako | G. dewevrei | 50.00 ± 28.57 | High (27 species) |

| Matchenje | M. macrostachyum | 113.30 ± 32.82 | Medium |

| Mapendo | M. macrostachyum | 34.33 ± 32.34 | Weak |

| Source of Variation | df | SSD | MS | F-Value | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campsite | 5 | 14,390 | 2878.10 | 16.88 | 0.0078 | *** |

| Species | 26 | 63,996 | 2461.40 | 14.44 | <0.0020 | *** |

| Interaction camp. -Spe. | 130 | 146,321 | 1125.50 | 6.60 | <0.0002 | *** |

| Residues | 324 | 55,229 | 170.50 |

| Campsite | Number Total (Individual) | Statistic Group |

|---|---|---|

| Mananasi | 1299 | a |

| Apeyole | 973 | ab |

| Matchenje | 556 | bc |

| Meiako | 449 | c |

| Mapendo | 219 | c |

| Putakasembe | 136 | c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kasoki, L.M.; Essouman, P.F.E.; Musavandalo, C.M.; Wamba, F.R.; Makanua, I.D.; Nguba, T.B.; Mavakala, K.; Mweru, J.-P.M.; Tsakem, S.C.; Babale, M.; et al. Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainable Management of Forest Resources in a Socio-Cultural Upheaval of the Okapi Wildlife Reserve Landscape in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Forests 2025, 16, 1523. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101523

Kasoki LM, Essouman PFE, Musavandalo CM, Wamba FR, Makanua ID, Nguba TB, Mavakala K, Mweru J-PM, Tsakem SC, Babale M, et al. Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainable Management of Forest Resources in a Socio-Cultural Upheaval of the Okapi Wildlife Reserve Landscape in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Forests. 2025; 16(10):1523. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101523

Chicago/Turabian StyleKasoki, Lucie Mugherwa, Pyrus Flavien Ebouel Essouman, Charles Mumbere Musavandalo, Franck Robéan Wamba, Isaac Diansambu Makanua, Timothée Besisa Nguba, Krossy Mavakala, Jean-Pierre Mate Mweru, Samuel Christian Tsakem, Michel Babale, and et al. 2025. "Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainable Management of Forest Resources in a Socio-Cultural Upheaval of the Okapi Wildlife Reserve Landscape in the Democratic Republic of the Congo" Forests 16, no. 10: 1523. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101523

APA StyleKasoki, L. M., Essouman, P. F. E., Musavandalo, C. M., Wamba, F. R., Makanua, I. D., Nguba, T. B., Mavakala, K., Mweru, J.-P. M., Tsakem, S. C., Babale, M., Nzuzi, F. L., & Michel, B. (2025). Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainable Management of Forest Resources in a Socio-Cultural Upheaval of the Okapi Wildlife Reserve Landscape in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Forests, 16(10), 1523. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101523