1. Introduction

The increasing deployment of photovoltaic (PV) technologies has made solar energy one of the primary sources of electricity globally. However, integrating solar power into utility networks faces a number of obstacles due to its inherent intermittent nature and variable output based upon solar irradiance. The two major aspects of solar irradiance are governed by deterministic astronomical cycles and stochastic meteorological conditions; therefore, it is imperative to be able to accurately forecast the amount of solar irradiance that will be available to the grid for stability purposes, optimal operation of energy storage systems, and to participate efficiently within the electricity market [

1,

2].

Time series of solar irradiance have a specific double structure. They display a strong deterministic periodicity (e.g., diurnal and seasonal cycles) driven by Earth’s rotation and orbit. Their behavior is physically predictable by well-established physical laws. In addition to the deterministic aspect, time series of solar irradiance also include random fluctuations, caused by the effects of clouds, aerosols, and humidity on the atmosphere [

3]. NWP (Numerical Weather Prediction) models can describe the large-scale dynamics of solar irradiance time series with great success, but they lack the spatial resolution necessary for short-term site-specific forecasting [

4]. Statistical models such as ARIMA and traditional machine learning algorithms (such as Support Vector Regression) can identify local trends, but they fail to capture the nonlinear characteristics of high dimensional radiometric data [

5].

Recent years have seen the emergence of deep learning (DL) as the most successful method for time series forecasting. Architectures such as RNN (Recurrent Neural Network), LSTMs (Long Short-Term Memory networks), and CNN (Convolutional Neural Networks) have shown a superior capacity to capture the nonlinear relationships between variables [

6]. The traditional DL approaches consider solar irradiance as a general time series and feed raw data directly into “black box” models. Therefore, the neural network is forced to learn the well-known astronomical cycles of the time series again from the start, which can lead to slow learning and less interpretability of the results [

7]. Moreover, purely data-driven models generally lack the robustness in forecasting over longer horizons because the accumulated error is not corrected by the physical constraints.

Physics-aware DL frameworks have been developed to combine the physical knowledge about the signal into the model architecture. Therefore, models can be more accurate and transparent than traditional DL models. Techniques for decomposing signals, e.g., Fourier analysis or wavelet transform, provide the theoretical foundation for separating the deterministic “physical” part of the signal from the stochastic “meteorological” parts of the signal [

8]. Although hybrid models have been presented in the scientific community, only very few papers have investigated the interaction of explicit Fourier-based decomposition with various DL architectures (RNN versus CNN), depending on the forecast horizons.

This study introduces a new Physics-Aware Deep Learning Framework for forecasting solar irradiance. A novel approach using a Fourier-based signal decomposition technique is used to separate the input sequence into three independent components: a polynomial trend, a Fourier-based seasonal component, and a stochastic residual. These components are separately processed by dedicated neural network branches and then fused together. Thus, the proposed architecture includes an inductive bias in line with the physical principles governing the behavior of solar radiation. It is important to note that the term “Physics-Aware” in this context refers to physically motivated signal decomposition that incorporates known physical periodicities of solar radiation (diurnal and seasonal cycles), rather than physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) that embed physical laws directly into loss functions or architecture constraints.

Therefore, the main contributions of this study are as follows:

- 1.

Physics Aware Decomposition Framework: A new and interpretable architecture was introduced that explicitly models the trend, seasonality, and residuals of solar irradiance using Fourier basis functions to represent the astronomical periodicities of the signal.

- 2.

Comparative Architectural Evaluation: Four different DL architectures (RNN, LSTM, GRU, and CNN) were evaluated in terms of how the decomposition affects their performance relative to the “black-box” baseline models in 96 experiments.

- 3.

Horizon-Dependent Performance Insights: It was shown that the advantages of the physics aware decomposition do not depend uniformly on the horizon and that the advantages increase with the length of the horizon (up to 5.6 times better for long-term predictions of 3–6 h than for short-term predictions).

- 4.

Interpretability and Robustness: It was shown that the recurrent architectures (RNN, LSTM) benefit greatly from the explicit coding of periodic structures, whereas the convolutional architectures (CNNs) capture these structures inherently via the application of filters and, thus, allow a deeper insight in selecting suitable architectures for the solar forecasting task.

The remaining sections of this study are structured as follows:

Section 2 provides an overview of previous research in the fields of solar forecasting and signal decomposition.

Section 3 describes the proposed Fourier-based framework and neural architectures.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup and dataset.

Section 5 shows the results and discussion, and

Section 6 draws conclusions and suggest future directions.

2. Related Work

Deep learning techniques have become central to modern forecasting problems due to their ability to model nonlinear dynamics, temporal dependencies, and complex interactions among variables. This section reviews prior work by categorizing existing approaches according to their underlying methodologies, including recurrent neural networks, Convolutional Neural Networks, hybrid architectures, signal decomposition-based methods, and interpretable and attention-based models.

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are among the most widely used models for time-series forecasting because of their intrinsic ability to process sequential data. However, classical RNNs suffer from vanishing and exploding gradient problems, limiting their ability to capture long-term dependencies. To address these limitations, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) were introduced. LSTM-based forecasting models have been successfully applied across a wide range of domains, including solar irradiance forecasting, electricity load prediction, wind power estimation, and financial time-series analysis [

9,

10]. LSTM’s gating mechanism allows it to maintain important historical data across longer time frames that can be necessary for stationary and/or seasonally changing data. As an alternative, GRUs provide a simpler option requiring fewer parameters than LSTMs while providing equivalent or better performance at lower computational costs [

11]. Additionally, many studies have shown that using bidirectional RNNs has improved forecast results by allowing the network to process the sequence in both the forward and reverse direction resulting in enhanced contextual knowledge and increased forecast accuracy [

12]. However, RNN-based approaches often require a great deal of hyperparameter tuning and can be less successful when used on noisy and/or highly variable data.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) were originally designed for image processing but have recently become popular for time series forecasting because they can identify temporal patterns through convolutional filters that operate locally along time dimensions. The one dimensional CNNs have been successfully applied to weather forecasting, predicting the amount of energy generated from solar power, analyzing traffic flow and other applications [

13,

14]. CNNs are very useful when working with high resolution temporal and/or spatial data (e.g., sky images; gridded meteorological data). They also excel at extracting features in a hierarchical manner and, therefore, are well suited to identifying short-term variability. The CNN lacks an intrinsic memory component that restricts its ability to model long-range temporal relationships unless the CNN is used in conjunction with other architectures.

To counteract the disadvantages of a single model approach, hybrid structures that combine CNNs and RNNs receive much attention. CNN-LSTM models utilize CNN layers for extracting feature from images and LSTM layers for modeling temporal dependencies [

15], which has been shown to outperform the performance of CNN only models and RNN only models with respect to both solar power and energy demand forecasting. Hybrid structures can be more complex than simple CNN-RNN combinations, including but not limited to attention mechanisms, residual connections, and optimization algorithms. For example, some CNN-LSTM hybrids use an attention mechanism to allow CNN layers to selectively focus on the most important features at each time step, leading to improved performance [

16]. Similarly, transformer-based hybrids extend the previous concepts by utilizing a self-attention layer to capture global dependencies while also maintaining the sequence-learning capabilities of recurrent layers [

17].

There are many signal decomposition methods available to handle nonstationary and noisy time series data commonly found in real world applications. Some examples include, but are not limited to, the Fourier Transform, Wavelet Transform, Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD), and Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) [

18]. The use of VMD in conjunction with deep learning has provided superior results when compared to other decomposition methods due to its ability to isolate multiple intrinsic modes corresponding to various frequency ranges [

19]. In general, the individual components of the decomposed signal are trained on separate neural networks, and the final predicted values are calculated by aggregating the output values of each network. These types of approaches have been used with success in a variety of areas, including but not limited to, solar irradiance, load demand, and financial forecasting [

20,

21].

Although these models perform extremely well in terms of prediction, they are generally considered to be poorly interpretable; therefore, researchers have used attention mechanisms and explainable AI techniques to improve interpretability of their forecast models. By assigning adaptive weights to either input features or specific time steps in the input data stream, attention layers provide insight into how the model makes decisions [

22]. Similarly, interpretable architectures, such as attention-based LSTM models and explainable CNNs, enable users to determine feature importance and temporal relevance [

23]. For use in both energy and climate related areas, which require high levels of transparency and trust in order to make decisions, the ability to understand why a particular decision was made is especially important.

In conclusion, the evolution of research in forecasting has moved from single, independent neural models toward hybrid, decomposition aware, and interpretable deep learning frameworks. RNNs continue to be an important aspect of temporal modeling, while CNNs offer enhanced feature extraction capabilities. Hybrid models that utilize both RNNs and CNNs, along with attention based models offer increased accuracy and robustness when compared to other models. Additionally, signal decomposition enhances performance by addressing the non-stationary nature of many time series datasets. Furthermore, the inclusion of interpretability mechanisms represent a critical development toward the creation of trustworthy and deployable forecasting systems.

3. Proposed Methodology

The overall methodology for development of a Physics-Aware Deep Learning Framework to predict solar irradiance will be presented in this section. A combination of Fourier-based signal decomposition and advanced deep learning architectures will provide the capability to produce highly accurate predictions while providing insights into how well the predictive model captures the physics of solar irradiance production.

In addition to the methodologies used to develop the predictive model, we will also provide the experimental design and details of all deep learning architectures, signal decomposition methods, and preprocessing techniques utilized in the study.

3.1. Study Area and Dataset Description

The dataset utilized in this study was produced during a three year period starting from 1 January 2017 and ending on 31 December 2019. Data collection occurred every 15 min throughout the three year period and resulted in a total of 96 observations for each day of the dataset and a total of 105,376 data points for the entire dataset [

24]. The data was obtained from the National Solar Radiation Database (NSRDB), which provides satellite-derived solar irradiance estimates with documented quality control procedures. The measurement site is located at coordinates that represent a semi-arid climate regime typical of the Middle Eastern region, with high solar resource availability and distinct seasonal patterns.

Due to its relatively high temporal sampling rate, our dataset is capable of capturing many of the smaller scale changes in the solar radiation field that are important for the production of high-accuracy, short-term forecasts of solar irradiance [

25].

Our dataset consists of a variety of different meteorological and solar irradiance related variables including:

Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI): Global horizontal irradiance represents the total amount of shortwave solar radiation that reaches a horizontal surface and is expressed in units of watts/square meter. It represents both the amount of direct normal irradiance reaching the surface and the amount of diffuse horizontal irradiance reaching the surface.

Temperature: Ambient air temperature, expressed in degrees celsius, influences both atmospheric conditions and the efficiency of solar panels.

Dew Point Temperature: The dew point temperature is the temperature at which ambient air becomes saturated with moisture and is an indicator of humidity levels in the atmosphere. High dew points indicate high humidity levels, which can reduce the transmission of solar radiation through the atmosphere.

Relative Humidity: Relative humidity is the percent of water vapor present in the air compared to the maximum amount possible at the current temperature. Like dew point temperature, relative humidity is an indicator of humidity levels in the atmosphere and, thus, can influence the amount of solar radiation that can reach the Earth’s surface.

Solar Zenith Angle: The solar zenith angle is the angle between the sun and the vertical direction at the location where the measurement is being taken. As a geometric parameter it plays a major role in determining the amount of solar radiation reaching the Earth’s surface [

26].

Surface Albedo: Surface albedo is the ratio of the amount of solar radiation reflected by the Earth’s surface back towards the atmosphere to the total amount of solar radiation incident upon the surface. It plays a major role in controlling the radiative balance between incoming solar radiation and outgoing terrestrial infrared radiation.

Atmospheric Pressure: Atmospheric pressure is a measure of the barometric pressure at the surface of the Earth, typically expressed in units of millibars. It controls the density of the atmosphere and thus the amount of solar radiation absorbed by gases in the atmosphere.

Wind Speed: Wind speed is a measure of the speed of the surface winds at a given location and time. It influences local atmospheric conditions and cloud dynamics and, thus, can influence the amount of solar radiation reaching the surface.

We have chosen to retain global horizontal irradiance (GHI) as the target variable and have included all other meteorological parameters listed above as input features for our predictive models. In contrast to some previous studies, we have omitted clear sky GHI estimates as well as direct normal irradiance (DNI) and diffuse horizontal irradiance (DHI) from our input feature set. This was performed to simulate real-world operational conditions in which DNI, DHI and clear-sky GHI may not be readily available.

3.2. Preprocessing Techniques

Our preprocessing pipeline is designed to convert our raw time-series data into a form that is compatible with deep learning architectures [

27]. Our preprocessing pipeline consists of four major steps:

3.2.1. Temporal Index Creation

Our raw time-series data consisted of several separate columns containing the year, month, day, hour, and minute of each data point. Using these temporal components, we created a single date-time index that could be properly ordered chronologically and used to generate sequential training samples for our deep learning models [

28]. The date-time index (

) was generated using the following equation:

3.2.2. Cyclic Temporal Feature Extraction

As mentioned earlier, solar radiation varies significantly due to two primary sources of periodic variation: the daily diel cycle and the yearly seasonal cycle. To preserve the cyclic nature of the temporal features in our data and to prevent problems with discontinuities caused by the raw temporal values (i.e., the hour of day transitions from 23 to 0), we applied sinusoidal encoding transformations to extract cyclic temporal features [

29]. Specifically, we applied the following equations to the hour of the day

h and the day of the year

d:

These transformations map the cyclical temporal information onto a continuous two-dimensional space where temporally adjacent points are close together in terms of their feature vectors regardless of whether they represent a large or small discontinuity in their raw values. The temporal columns (year, month, day, hour, minute) are then discarded to remove redundant temporal information from the dataset.

3.2.3. Imputation of Missing Values

Missing values arise frequently in solar irradiance datasets; they occur when sensors malfunction, when there are data transmission errors, and during regular maintenance of the instrumentation. To address missing data, we used a bidirectional temporal imputation technique, which uses two passes of the dataset—first forward-fill and then backward-fill—to replace missing values with nearby values [

30]:

Our method utilizes the temporal correlation of meteorological variables to estimate missing values by utilizing proximal values as reasonable estimates for missing values. It is a bidirectional approach, so it will handle missing values at either the start or end of the time-series properly. It is important to note that forward-fill is applied first, and backward-fill is only used as a fallback for values at the beginning of the dataset that cannot be forward-filled. This imputation is applied to the complete dataset before the train/test split. Since forward-fill only uses past values, this approach does not introduce information leakage from future observations.

3.2.4. Normalization of Data

To improve the training of neural networks and maintain numerical stability for all input features and the target variable, we utilized Min-Max normalization. In Min-Max normalization, values are transformed to the range [

31]:

We fit separate Min-Max scalers for the feature matrix and the target vector on the training data’s statistics. Once these scalers have been trained, we apply them to the test data to avoid data leakage. For metrics and interpretations, we transform the model’s predictions back to their original scale. The Min-Max normalization was applied with range . For computing evaluation metrics and generating predictions, the model outputs are inverse-transformed using the stored scaling parameters: , where and are derived from the training set only.

3.2.5. Chronological Train/Test Split

We temporally partitioned the dataset to preserve the temporal nature of time-series data. Therefore, the training set contains data from January 2017 through December 2018 (approximately 70,000 samples), and the testing set contains the entire year of 2019 (approximately 35,000 samples). This chronological train/test split preserves the temporal nature of time-series data and, thus, provides a more realistic representation of how well a model performs in terms of forecasting future data that is unavailable during the training phase.

3.3. Generation of Overlapping Sequences Using Sliding Windows

For deep learning models that perform time-series forecasting, it is necessary to create input/output pairs from the sequential data. We created overlapping sequences of past observations that were used to forecast future Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) values using a sliding window approach to generate input/output pairs. Assuming a sequence of observations

and the corresponding target values

, for a given window size

w and a prediction horizon

h, the input/output pairs can be formed as follows:

Here, the index

i varies from 1 to

, and therefore, we obtain

training samples. Using the sliding window approach described here allows us to perform multi-step-ahead forecasting by simply modifying the horizon parameter

h. As such, we do not need to modify the underlying network architecture to enable the models to forecast GHI values at different lead times.

3.4. Signal Decomposition Physics-Inspired Framework

One of the most unique aspects of the proposed framework is the incorporation of physics-inspired signal decomposition techniques to enhance the interpretability of the model and improve the quality of its predictive capabilities [

32]. Signals related to solar irradiance display a variety of patterns, and they can be decomposed into several components, including (a) deterministic trends, (b) periodic seasonality, and (c) random residuals. These decomposition approaches mirror the physical understanding of the behavior of solar radiative transfer processes and allow for specific processing of each individual component [

33,

34].

3.4.1. Trend Component and Polynomial Basis Functions

The trend component of the signal describes the slowly changing, non-periodic variations in the solar irradiance signal. We describe the trend component using a polynomial basis functions approach, where the input signal is projected onto a polynomial basis of order

p:

Here,

represents normalized time positions inside the sequence window, and

n represents the length of the sequence. The trend component can be obtained by projecting the input signal

onto this polynomial basis by means of least squares estimation:

In our implementation, we utilized a polynomial with terms (i.e., maximum degree , corresponding to a cubic polynomial) since we wanted to allow enough flexibility to capture gradual changes while minimizing the risk of overfitting to noise. The choice of was determined empirically, balancing model expressiveness with generalization capability. The trend component captures the long-term, slowly evolving patterns in the irradiance signal that are influenced by a variety of factors, including seasonal variability, instrumental degradation, and other sources of long-term drift.

3.4.2. Seasonality Component and Fourier Basis

The trend component will capture the overall trend of irradiance over time and can be modeled using linear regression, polynomial regression, or even a simple moving average. The seasonality component captures the cyclical nature of irradiance due to the day/night cycle and other natural occurrences that occur at regular intervals [

35]. Fourier basis decomposition is used to decompose the seasonality component of the irradiance data into harmonic terms that can be represented using sine and cosine functions. Specifically, we employ a Fourier basis with

K harmonics:

where

represents normalized time positions within the sequence window. The seasonality coefficients are obtained via least squares estimation, analogously to the trend component:

In our implementation, we use

harmonics, selected empirically to balance model complexity with the ability to capture diurnal cycle patterns. The frequencies are defined relative to the window length rather than fixed physical periods (e.g., 24 h), allowing the model to adapt to different window sizes. The residual component captures all of the remaining variation in irradiance that has not been accounted for by the trend and seasonality components. This residual component would include anything that cannot be predicted such as weather-related variations and errors in the measurements of the data. The residual component is important in predicting irradiance because many of the unpredictable variables are caused by clouds which is one of the largest contributors to prediction error. Therefore, a three component decomposition allows for a more accurate representation of the solar irradiance data and also improves interpretability of the predictions made by the models. Each of the components within the decomposition allow for a better understanding of how the model is making predictions based on the trends and seasonality in the data as well as how much of the data remains unpredicted. This improved interpretability is beneficial when trying to understand how well the models perform and what needs to be performed in order to improve them [

36,

37].

6. Conclusions and Future Research

In this paper we have developed an interpretable deep learning framework for the prediction of solar irradiance, which is based on a Fourier decomposition of the signal together with a convolutional neural network (CNN). Both, the prediction quality of our method, as well as its interpretability, are crucial for solar-energy-related applications. The major contributions of this work are as follows:

- 1.

Physics-Aware Signal Decomposition: We introduced a new decomposition method of the solar irradiance signal, which divides the signal into trend, seasonal, and residual components, using polynomial and Fourier-based functions. Our decomposition has a clear relation to the physical processes influencing solar radiation and, therefore, allows us to apply special methods for every single component.

- 2.

Comparison of Architectures: In order to determine the most suitable architecture among the given four architectures (RNN, LSTM, GRU, CNN), we performed a systematic comparison of the architectures within the two categories, namely (a) generic architectures and (b) Fourier-based architectures, resulting in a total number of experiments with varying combinations of three window sizes and four prediction horizons.

- 3.

Improved Interpretability: The three-stack architecture provides insight into how every single component contributes to the final prediction and, thus, offers a possibility for the validation of predictions made by a domain expert.

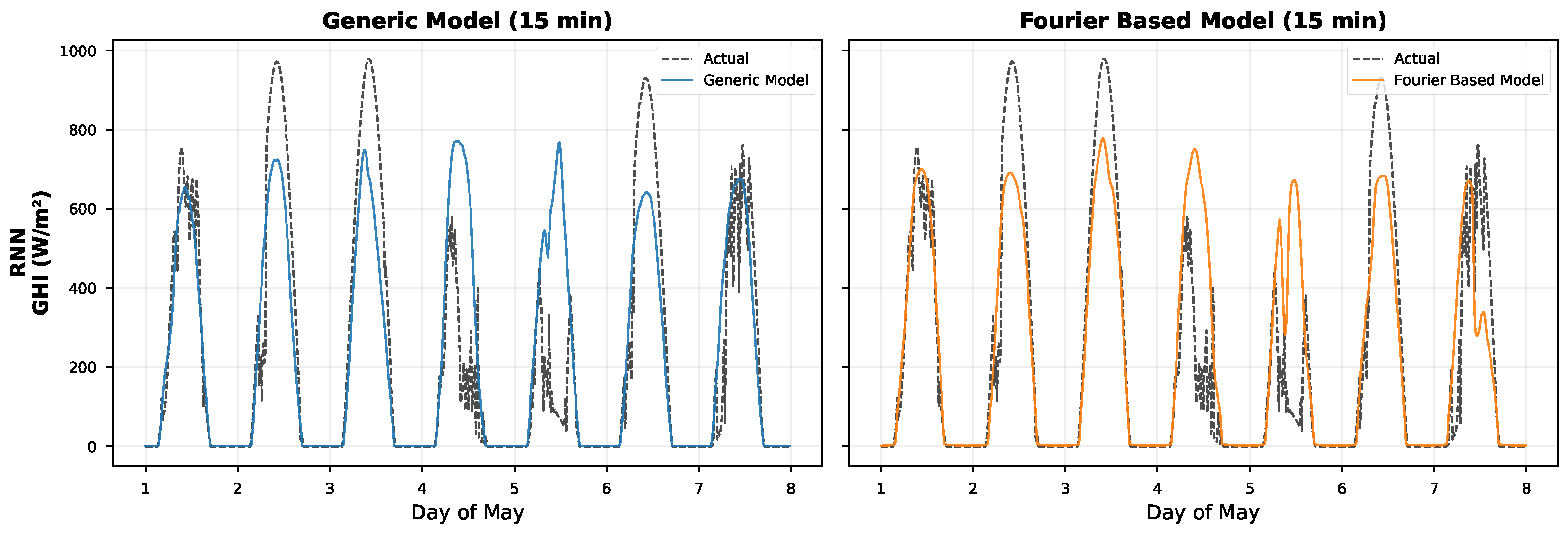

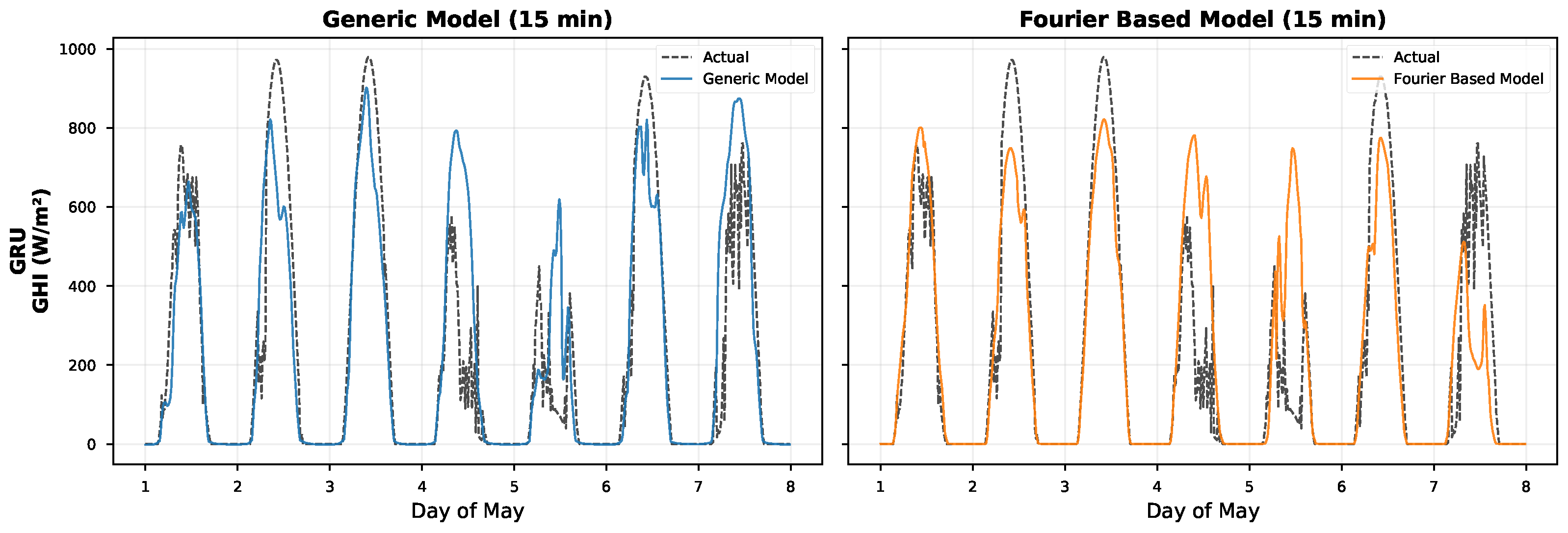

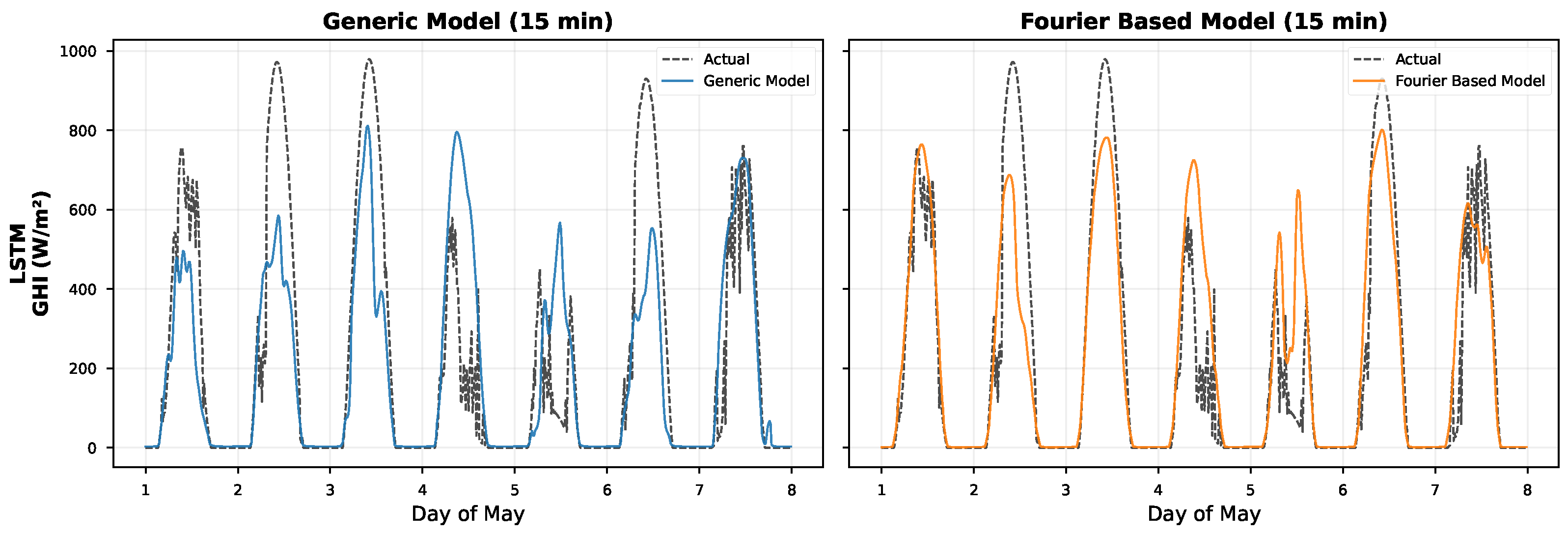

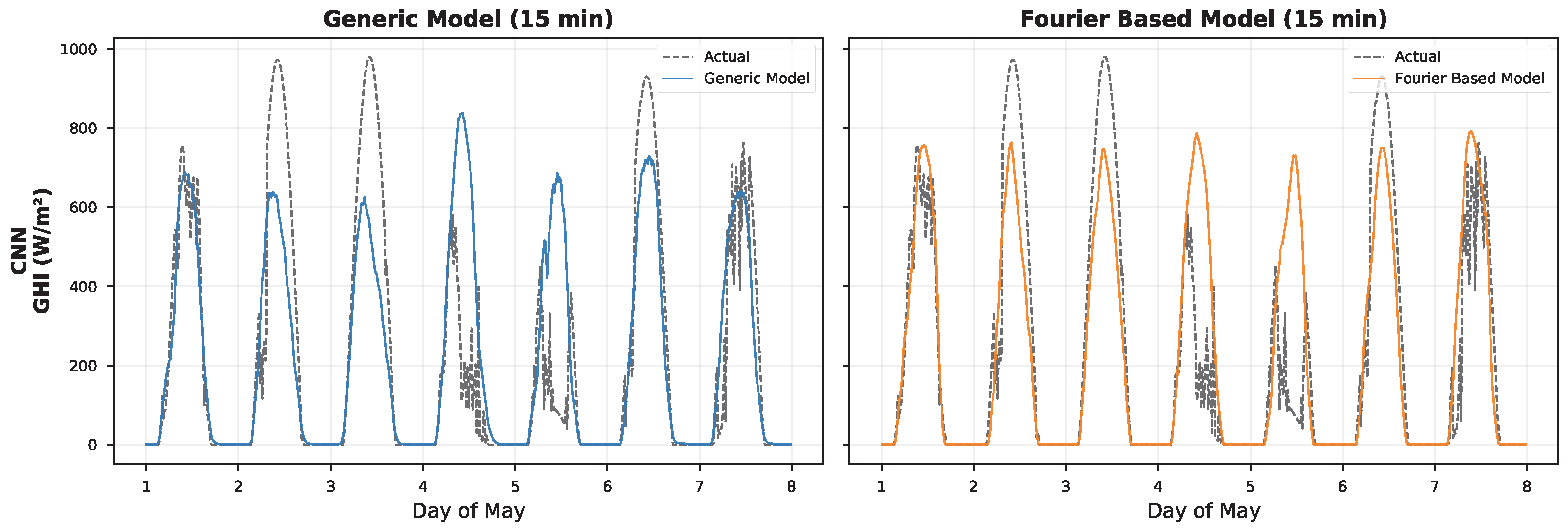

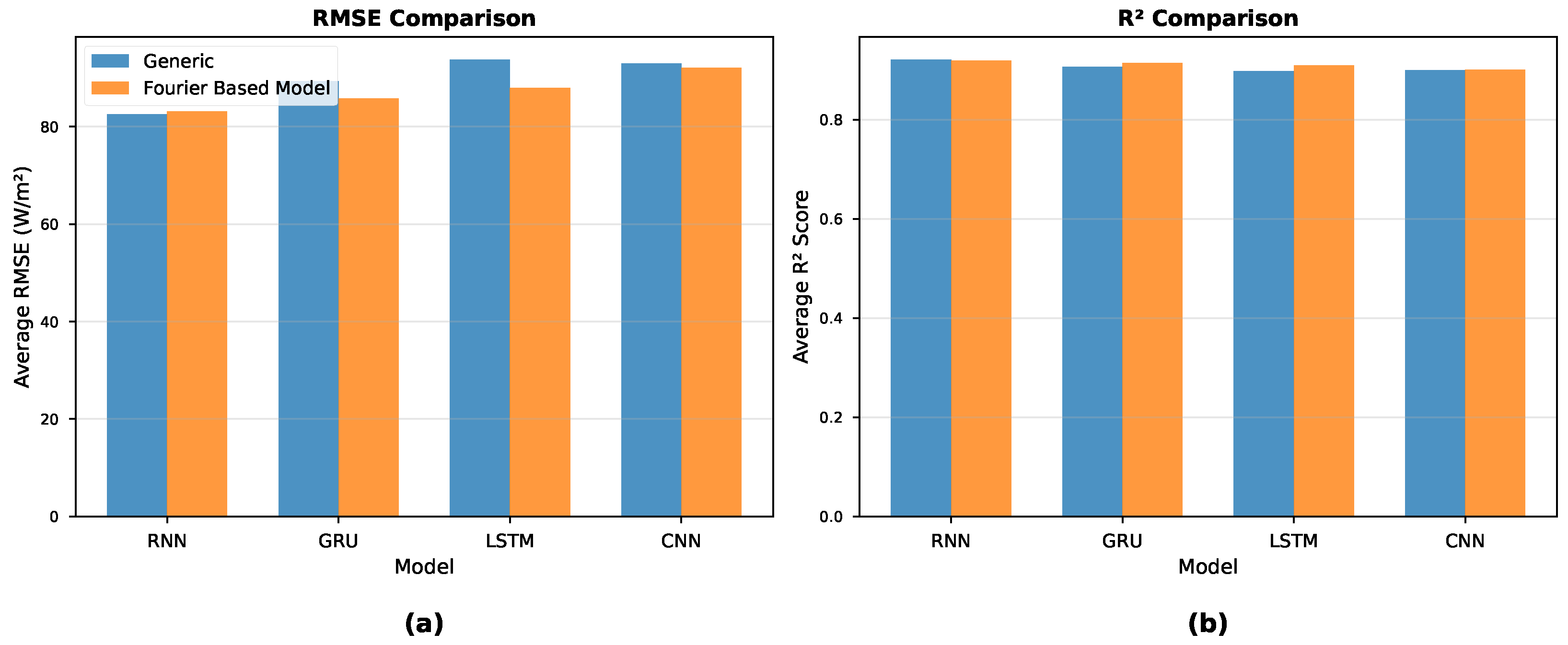

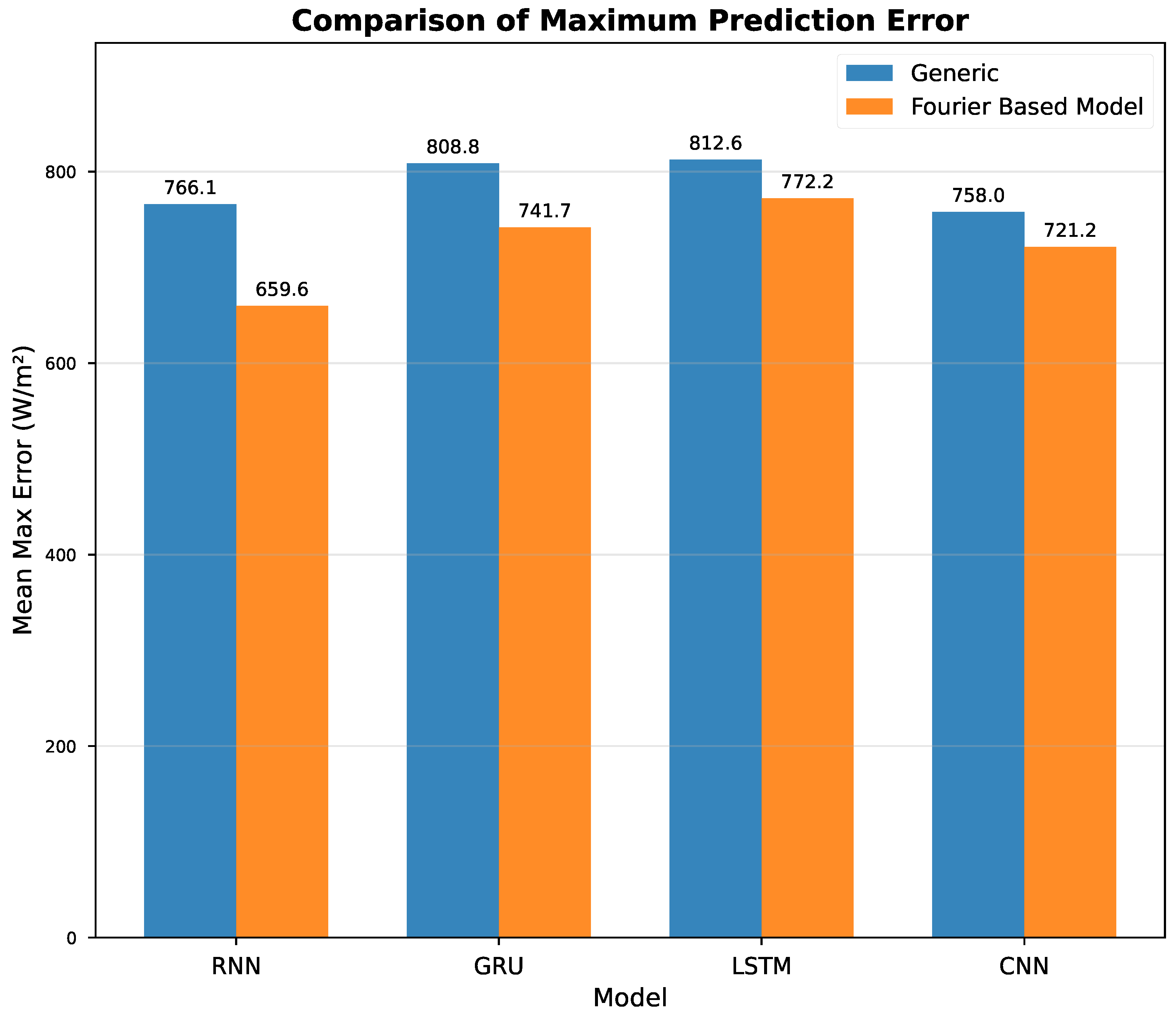

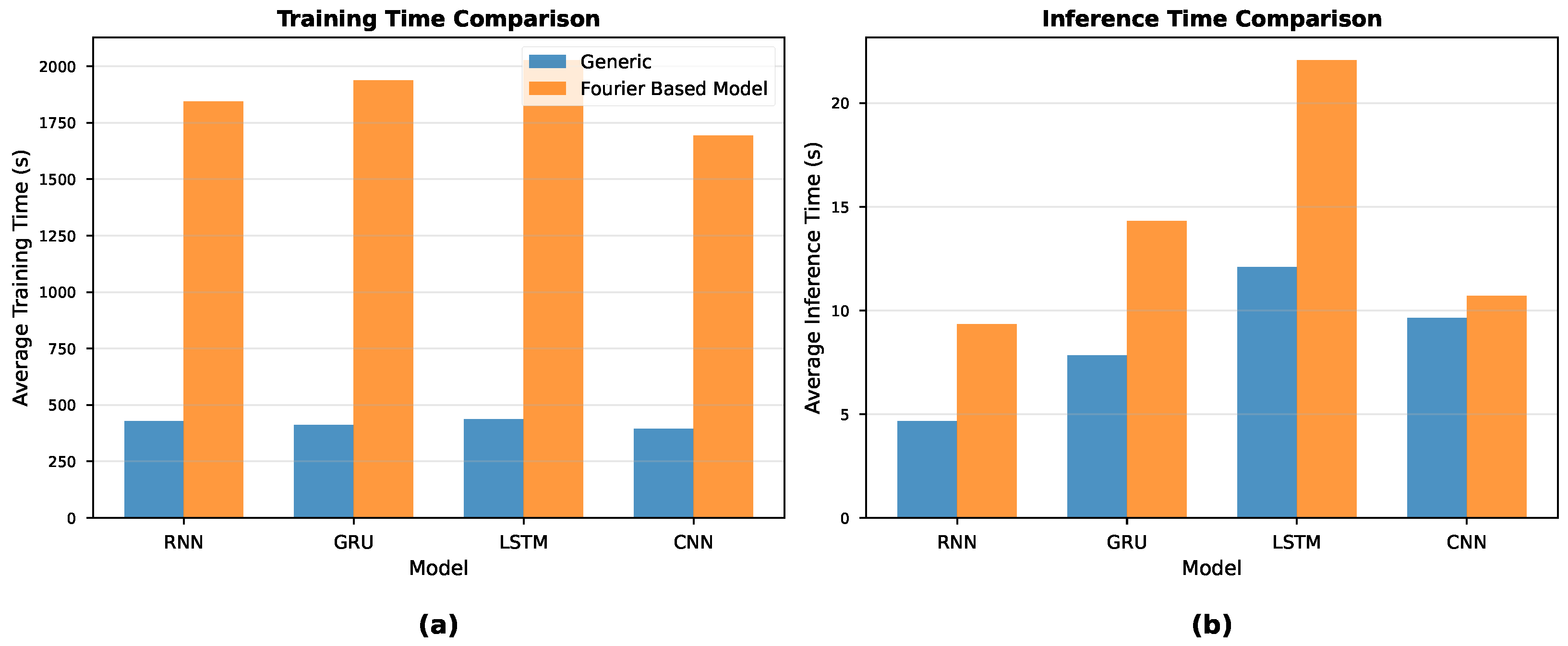

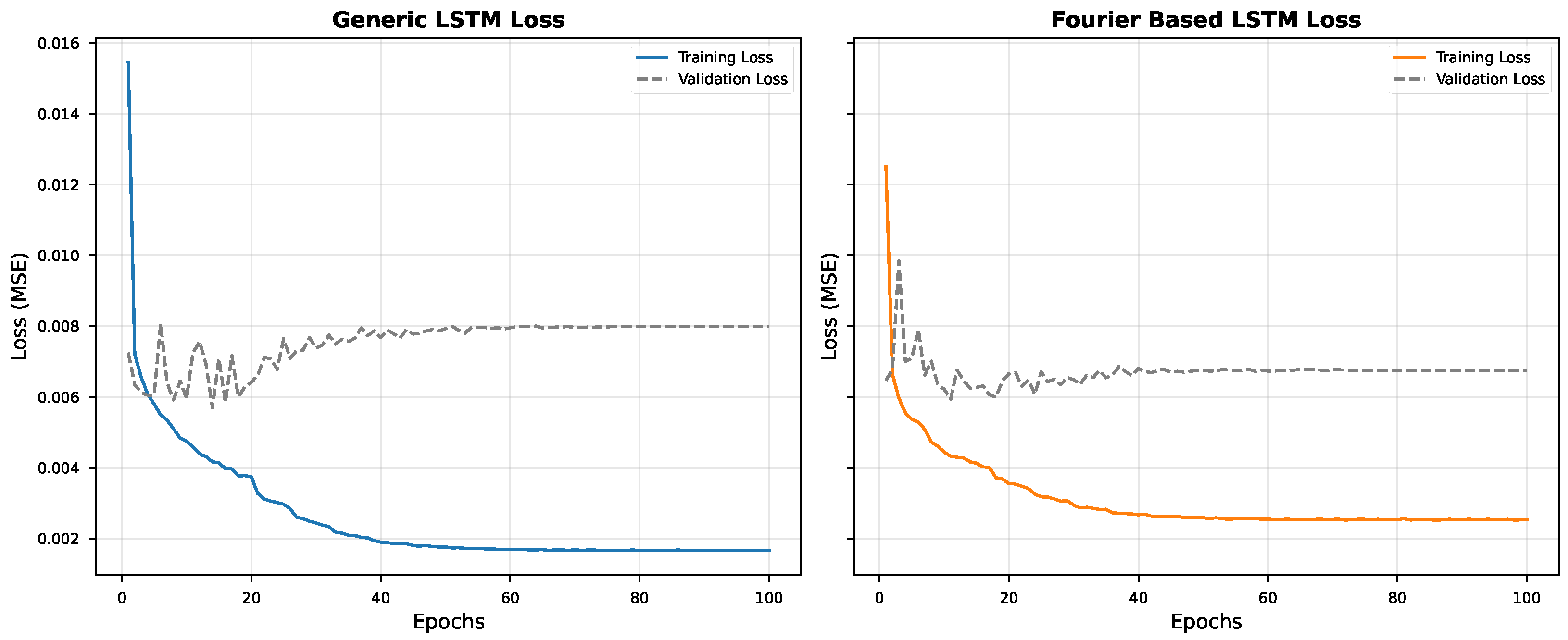

We found that the Fourier-based GRU achieved the best performance over all architectures with respect to both Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE = 78.63 W/m2) and Coefficient of Determination () at the best configuration of the parameter set (window size: 6 h (24 steps); prediction horizon: 15 min). The finding that simpler architectures (RNN, GRU) outperformed the more complex LSTM warrants discussion. We hypothesize that the Fourier-based signal decomposition effectively removes the deterministic periodic components from the input signal, leaving a residual that is more stationary and exhibits shorter-term dependencies. This preprocessing step reduces the need for the sophisticated gating mechanisms in LSTMs, which are designed to selectively remember or forget information over long sequences. When the long-term periodic structure is explicitly modeled by the Fourier basis, the simpler gating structures of GRUs (or even vanilla RNNs) are sufficient to model the remaining stochastic variations, while the additional parameters in LSTMs may lead to overfitting on the residual component. Among the recurrent architectures, we also find that RNN and GRU achieved the highest prediction accuracy, whereas LSTM showed a slightly worse performance. The CNN–Fourier model (RMSE = 83.56 W/m2; R2 = 0.9188) performed competitively and even better than the two LSTM variants. Compared to their generic counterparts, the Fourier-based models of this study show the same or even better prediction accuracy, but they provide the additional benefit of being understandable. Furthermore, we found that the Fourier-based GRU outperformed the generic GRU by 6.6% in terms of RMSE, and the Fourier-based LSTM outperformed the generic LSTM by 8.0%. As expected, the models suffer from a predictable degradation of prediction accuracy when increasing the prediction horizon. Specifically, the R2 values decrease from about 0.93 at prediction horizons of 15 min to about 0.87 at horizons of 3 h.

Future Research Directions

There are some interesting possibilities for further research based on the findings and limitations of this study. A limitation of the current work is the focus on comparing Fourier-based models against their generic counterparts without including classical baselines such as persistence (last-value) forecasting, linear regression, or traditional machine learning methods (SVR and gradient boosting). Future work should include these baselines to provide a more comprehensive performance context. For instance, we could combine multiple Fourier-based models by applying ensemble methods so as to increase both prediction accuracy and the robustness of uncertainty estimation. Another possible direction of research is to develop incremental learning strategies, allowing models to adapt to changing atmospheric conditions and sensor drift without full re-training. Additionally, we may expand the scope of our framework to enable simultaneous prediction of multiple future time steps, thereby generating comprehensive forecasting profiles for energy scheduling applications.