1. Introduction

Recently, the European Space Agency has embarked on the Low Earth Orbit (LEO) Cargo Return Services (LCRS) program [

1], an initiative designed to develop autonomous European capabilities for cislunar operations utilizing Ariane-6 launches from Kourou Spaceport (French Guiana). Despite significant background in spacecraft systems and orbital mechanics, comprehensive end-to-end mission design studies—validating whether European systems can execute autonomous Earth-to-Gateway transfers using exclusively European infrastructure—have been limited so far. Existing analyses focus primarily on separated trajectory segments or on spacecraft subsystem performance, lacking integrated assessments of complete mission scenarios that simultaneously account for launch vehicle constraints, multi-body orbital mechanics, propulsion limitations, and operational requirements. The research presented here directly addresses this critical gap by performing a systematic analysis of complete Earth-to-Gateway transfer architectures.

The current circumstances imply a narrow decision window. U.S. commercial providers offer rapidly maturing cislunar transportation capabilities that could establish market dominance before European systems reach operational status. Chinese autonomous cargo operations continue progression toward independent lunar infrastructure. Europe, however, has so far remained absent from this operational landscape. While long-term strategic initiatives such as LCRS and Argonaut (Europe’s lunar lander program) exist, no European missions are forecast to achieve operations in the cislunar environment for the next five to eight years, risking that Europe will belatedly arrive when foundational rules and partnerships for lunar operations have already been established by other actors.

Cislunar trajectory optimization represents one of the most challenging problems in modern astrodynamics, central to enabling sustainable lunar exploration and establishing permanent human presence beyond Low Earth Orbit [

2]. The difficulty stems from the fundamental nature of multi-body gravitational dynamics, where spacecraft motion in the Earth–Moon system cannot be described by closed-form analytical solutions. Near Rectilinear Halo Orbits (NRHOs) [

3] around the Moon exemplify this challenge: these orbits exist within the chaotic regime of the Circular Restricted Three-Body Problem (CR3BP, consult e.g., [

2]), exhibiting extreme sensitivity to initial conditions and perturbations. The resulting trajectory design problem is characterized by highly non-convex solution spaces, multiple local optima, and stringent operational constraints on propellant budget, mission duration, and rendezvous timing. Traditional two-body Keplerian mechanics, which govern most Earth-Orbit operations, provide no meaningful approximation in this domain, necessitating fundamentally different approaches to trajectory design and optimization.

In the present study, the emphasis is placed on our methodological contribution: we propose a comprehensive mission design study employing hybrid optimization techniques (see e.g., [

4,

5]) to address the Earth-to-NRHO transfer problem [

6]. While the techniques developed are broadly applicable to a wide range of cislunar mission scenarios, the European Space Agency’s LCRS program serves as the primary motivating case study. This application represents a compelling and strategically relevant challenge, and therefore provides the operational context for demonstrating the feasibility and performance of autonomous European access to NASA’s Lunar Gateway [

7].

The Lunar Gateway, positioned in a synodic resonant NRHO around the Moon, constitutes a critical infrastructure element in humanity’s travels to the Moon. Unlike conventional Low Lunar Orbit stations, the Gateway’s NRHO provides continuous Earth communication and enables access to any point on the lunar surface with minimal spacecraft velocity change budget. However, these operational advantages come at the cost of significantly improved Earth–Moon transfer trajectories design. The orbit’s highly elliptical geometry, combined with strong gravitational perturbations from Earth, Moon and Sun, creates a dynamic environment that is fundamentally different and more challenging (from a classical orbital mechanics point of view). Rendezvous operations require precise timing, as the orbit’s orientation and altitude significantly vary throughout its period, and small trajectory errors can lead to large deviations due to the chaotic nature of the dynamics involved.

Our research directly addresses this gap through systematic mission design analyses for complete Earth-to-Gateway cargo transfer scenarios. This will enable us to investigate whether European lunar cargo services represent achievable objectives worthy of sustained investment, or they require pragmatic reassessment.

To tackle the related challenging optimization problem, a two-stage hybrid scheme is employed. The first stage uses a genetic algorithm (GA) heuristic for global search, to identify promising and feasible trajectory regions. The second stage refines the initial solution guess (or guesses) produced by the global search, using an efficient local optimizer based on the sequential quadratic programming (SQP) method, since SQP rapidly converges to a high-precision, dynamically feasible solution.

The article is structured as follows.

Section 2 details the mathematical formulation of the optimization problem, including the equations of motion and the multi-arc trajectory scheme adopted, and the structure of the associated nonlinear programming (NLP) model.

Section 3 describes the hybrid optimization approach, explaining the distinct roles of the GA and SQP stages, as well as their integration.

Section 4 presents the numerical results for a cargo mission case study, demonstrating the efficiency of the approach adopted.

Section 5 provides concluding remarks and discusses potential avenues for future enhancements.

2. Problem Statement

At its core, the problem of designing a spacecraft trajectory is an issue of optimal control, see e.g., [

8,

9]. The spacecraft’s movement is determined by a set of complicated physical laws—the differential equations of motion—which account for the gravity of the Earth, Moon, and Sun, while the spacecraft’s position, velocity, and mass define its state at each time moment. The fundamental challenge is to find the optimal control option to guide the spacecraft from its starting point to its final destination while minimizing a chosen performance index, such as the total amount of fuel consumed. The trajectory must satisfy a set of crucial mission constraints, like arriving at the correct orbit, not crashing into any celestial bodies, and staying within the physical limits of the spacecraft’s engine performance. To solve this problem, we must create a precise mathematical model of the spacecraft’s dynamics, define exactly what we want to optimize as the objective function, and clearly lay out all the rules and boundaries that constitute the constraints of the optimization problem.

State vector and equations of motion. The state vector, denoted by

, is the set of variables that uniquely describes the dynamics condition of the vehicle at any time t. The equations of motion are expressed in an Earth-Centered Inertial (ECI) reference frame, which is aligned with the J2000 epoch (a standard celestial reference frame in astronomy, see [

10]). The system state

is represented by a seven-dimensional vector including position

, velocity

, and mass m(t):

where

and

are the ECI position and velocity vectors. The spacecraft’s acceleration,

, is decomposed into gravitational, propulsive, and disturbance terms:

Here,

is the non-conservative propulsive acceleration, which acts as the control variable. Other non-conservative perturbations, such as solar radiation pressure or atmospheric drag, which would be included in the

term in Equation (

2), have limited relevance for Earth–NRHO transfers and are neglected.

The dominant term,

, represents the combined gravitational force from all celestial bodies included in the model. Instead of a simple two-body problem (e.g., just Earth and the spacecraft), this term represents an n-body problem, summing the gravitational forces exerted by the Earth, Moon, and Sun simultaneously. This high-fidelity model is essential for accurately capturing intricate dynamics of cislunar space. The gravitational acceleration is given by:

Here, the gravitational acceleration

is composed of the primary two-body attraction from Earth and the perturbing effects of other celestial bodies. The first term,

, represents the acceleration due to Earth’s gravity, where

is Earth’s gravitational parameter and

is the position vector of the spacecraft in the Earth-Centered Inertial frame (see e.g., [

2]). The summation

, accounts for the gravitational influence of n third-body perturbers (such as the Sun and Moon). For each perturbing body j,

is its gravitational parameter and

is its position vector in the ECI frame. The expression within the parentheses consists of two components: the direct term,

, which is the gravitational acceleration exerted by body j directly on the spacecraft, and the indirect term,

, which corrects for the non-inertial acceleration of the Earth due to that same body. Finally, the change in spacecraft mass is exclusively due to propellant consumption. This is governed by the thruster’s performance, specifically its thrust magnitude

and specific impulse

:

where

is the standard gravitational acceleration at sea level. This equation links the vehicle dynamics directly to the efficiency of the propulsion system, as a higher

results in a lower mass flow rate for a given thrust level, thus saving propellant.

Multiple trajectory arcs and NLP problem formulation. To make the continuous optimal control problem solvable with numerical methods, the trajectory is subdivided (discretized) into a sequence of distinct segments. In our formulation, we assume that the entire trajectory is partitioned into a sequence of ballistic arcs, where the spacecraft simply coasts under the influence of gravity. An impulsive maneuver is executed at the initial time of each arc, denoted as an impulsive , is applied to represent a propulsive burn. Between these maneuvers, the spacecraft’s path is governed solely by then n-body dynamics.

This approach effectively transforms the problem from one with a continuous control function (the engine thrust over time) into a finite-dimensional nonlinear programming (NLP) problem. To adhere to the practical limits of a real propulsion system, the total number of maneuvers is fixed at a maximum of N, where N represents the number of connection points, or nodes, along the trajectory. The value N = 6 is selected in our study, considering that at most 5 maneuvers can effectively attain the required transfer.

The problem is now defined by a finite set of decision variables to be determined. These are:

The three components of the impulsive velocity change , applied at each of the N maneuver points.

The duration , of each of the ballistic arcs, expressed as a non-dimensional fraction of an assigned maximum time T.

By structuring the problem this way, the trajectory can be constructed segment by segment. For any given set of decision variables,

, the full path is generated by sequentially applying each

and then integrating the equations of motion for the duration

. This ensures that the state of the spacecraft is continuous from one arc to the next. The problem is now reduced to finding the optimal set of variables

that minimizes an objective function

while satisfying a set of inequality constraints

and staying within the allowed bounds on the decision variables themselves. So the finite-dimensional NLP can be stated in its general form as:

where

represents the vector of decision variables, bounded by the lower and upper bounds

and

, respectively. The function components of

, are evaluated through the integration of the equations of motion (

1)–(

4).

Optimization objective and constraints. The specific optimization criterion is to minimize the propellant consumption. For the impulsive maneuvers considered here, this is physically equivalent to minimizing the total required velocity change, denoted by

. The objective function,

, to be minimized is therefore the sum of the magnitudes of all the impulsive velocity changes (

):

This objective is subject to a set of path and terminal constraints, collected in the vector

, which ensure the final trajectory meets all mission requirements. For the case study considered, these are expressed as a set of normalized inequalities:

where:

is the minimum geocentric altitude along the trajectory, constrained to .

is the final orbital inclination at arrival, constrained to .

is the maximum geocentric distance (apogee) of the transfer, constrained to to ensure the correct path is followed.

is the characteristic energy at the final perigee, constrained to

for a low-energy arrival. (see e.g., [

2])

are scaling factors used to normalize the constraints and improve the numerical conditioning of the NLP problem.

3. Optimization Approach

The solution of the nonlinear programming problem, formulated in

Section 2, is approached by iterative optimization algorithms that require repeated evaluations of the objective and constraint functions. In this work, the

functions are evaluated using a “black box”: a trajectory propagator that encapsulates the high-fidelity

n-body equations of motion. The NLP solver provides this propagator with a “candidate” decision vector

. The optimization process then necessitates the evaluation of the full trajectory. This is accomplished by the propagator executing a backward integration loop over the

segments, starting from the final arc and proceeding to determine the overall initial state. Given the pronounced dynamical instability inherent to NRHO within the multi-body environment, which makes forward integration numerically ill-conditioned, the trajectory is judiciously initiated via backward propagation from a selected arrival state on the NRHO, a strategy that allows for the identification and evaluation of different optimal solutions based on the chosen destination. The resulting state and the full computed trajectory are then returned to the NLP solver to calculate the objective cost and constraint values for the specific input vector of decision variables

.

The underlying multi-body dynamics render the solution space strongly nonconvex. This scenario poses significant numerical challenges for the NLP solver. Challenges include searching for a feasible solution, the existence of multiple local minima, and high sensitivity to the initial guess. Consequently, relying solely on traditional local optimization methods would not be sufficient: they may not find feasible solutions or could converge to a locally optimal solution and miss the global solution.. Therefore, a two-stage hybrid methodology is adopted to solve the NLP problem (

5). This overall strategy combines the strengths of global and local optimization algorithms aiming to drive the search for the global optimal decision vector:

First, a Genetic Algorithm (GA) is employed to robustly explore the nonconvex solution space. The GA through the black-box propagator identifies promising regions containing good guess solutions (see e.g., [

11,

12,

13,

14]).

Next, a sequential quadratic programming (SQP) method is used to refine the best solution found by the GA. Leveraging this strong initial guess, SQP provides rapid and precise convergence to the local optimum (consult e.g., [

15]).

Using the same black-box propagator for both the GA and SQP stages ensures that feasibility and cost are evaluated with an identical numerical model, guaranteeing consistency throughout the entire optimization process.

Penalty functions and constraint handling in GA. The genetic algorithm stage employs a penalty function approach to handle the complicated constraint structure of the problem. Rather than enforcing hard constraints, which could lead to widespread infeasibility within the population, a penalty scheme guides the evolutionary search toward constraint-compliant regions while preserving the needed “genetic diversity” for global scope search.

The fitness function

is therefore formulated as a weighted sum of the cost objective and multiple penalty terms:

Here, is the original objective function, W the associated weight, and the summation is intended over a total of penalty functions. Each term represents a specific penalty designed to enforce a mission constraint or a desired trajectory feature, while its corresponding weight is adapted as needed to balance its relative importance. The specific penalties, indexed by k, are reported here below.

- k = 1

Apogee corridor. A quadratic penalty is applied if the trajectory’s maximum geocentric distance, , falls outside the target range . This is crucial for achieving the necessary solar perturbations.

- k = 2

Apogee quadrant. A large constant penalty is applied if the apogee occurs in the wrong quadrant relative to the Sun-Earth line (i.e., if the dot product between the Sun’s position vector and the spacecraft’s apogee position vector is positive), ensuring the correct geometry for a WSB transfer (see e.g., [

16]).

- k = 3

Characteristic energy. A quadratic penalty is applied if the departure energy at the final perigee is outside the narrow range , ensuring a low-energy arrival.

- k = 4

Altitude at arrival. A quadratic penalty enforces the final minimum altitude to be within the target range .

- k = 5

Inclination at arrival. A quadratic penalty ensures the final inclination i falls within the target NRHO corridor .

- k = 6

Monotonic escape. A large constant penalty is applied if the spacecraft, after first exiting a predefined radius around the Moon, re-enters it. This critical constraint prevents inefficient lunar flybys.

- k = 7

Safety. A large constant penalty is added if the final minimum altitude drops below a critical safety threshold (e.g., 100 km), preventing atmospheric re-entry.

Penalties 1–3 (WSB trajectory shaping) guide the optimizer toward the characteristic high-energy, high-apogee WSB corridor [

6]. Penalties 4–7 (arrival and safety) ensure the trajectory meets its target conditions and operational limits. The choice of the weights is done after a few trial GA runs to balance the constraints influence; the specific values assigned to the weights (

) for the shaping objectives and the large penalty constants used for hard constraints are detailed in

Table 1. The candidate solutions identified by the GA are subsequently refined using an SQP algorithm.

The NLP solved during this local refinement stage is based on the mathematical model expressed by relations (

5)–(

7).

GA pseudocode and SQP pseudocode. For completeness, pseudocodes for general Algorithms 1 and 2 are included below (see e.g., [

15,

17]). Comments added to the pseudocodes are denoted by ▹.

| Algorithm 1 Pseudocode for a generic Genetic Algorithm (GA) |

- 1:

Given: - 2:

Fitness function to MINIMIZE - 3:

Decision encoding (real-valued, binary, etc.) - 4:

Population size N - 5:

Crossover rate , mutation rate - 6:

Tournament size k (for selection) - 7:

Elitism count E (usually 1–5% of N) - 8:

Max generations (or other stopping test) - 9:

Penalty function for constraint violation (optional) - 10:

procedure

Genetic_Algorithm - 11:

- 12:

▹ Random within bounds - 13:

for each do - 14:

▹; lower is better - 15:

end for - 16:

- 17:

while not do

- 18:

- 19:

- 20:

while do - 21:

- 22:

- 23:

if then - 24:

- 25:

else - 26:

; - 27:

end if - 28:

- 29:

- 30:

- 31:

- 32:

- 33:

end while - 34:

- 35:

for each do - 36:

- 37:

end for

- 38:

- 39:

- 40:

if then - 41:

- 42:

end if - 43:

end while - 44:

return - 45:

end procedure - 46:

function FitnessWithPenalty(x) - 47:

return - 48:

end function - 49:

function StoppingCondition(gen, BEST, G_max) - 50:

return - 51:

end function

|

| Algorithm 2 Pseudocode for a generic Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) algorithm |

- 1:

Given: - 2:

▹ Initial solution guess - 3:

▹ Initial multipliers (optional; else zeros) - 4:

▹ Initial Hessian approximation (e.g., ) - 5:

Tolerances: - 6:

Line-search parameters: - 7:

Penalty parameters: ▹ For exact-penalty merit - 8:

Max iterations: - 9:

procedure

SQP_Algorithm - 10:

; ; ; ; - 11:

repeat

- 12:

; - 13:

; ▹ Jacobian of equalities - 14:

; ▹ Jacobian of inequalities

- 15:

- 16:

- 17:

- 18:

if and and then - 19:

return - 20:

end if

▹ ---- Form and solve QP subproblem ---- ▹ Quadratic model of Lagrangian with linearized constraints: s.t.

- 21:

- 22:

- 23:

while do - 24:

- 25:

if then ▹ Check minimum step tolerance - 26:

▹ Optional fallback to reduce infeasibility - 27:

- 28:

break - 29:

end if - 30:

end while

- 31:

- 32:

▹, often - 33:

- 34:

- 35:

- 36:

- 37:

- 38:

if then - 39:

- 40:

else - 41:

▹ Powell damping factor - 42:

- 43:

end if - 44:

if then - 45:

- 46:

end if

- 47:

; ; - 48:

- 49:

until - 50:

return ▹ Best found; report termination reason - 51:

end procedure

|

4. Numerical Implementation and Results

The optimization process is built around a shared computational framework used by both the global and local stages. Trajectory propagation is handled by the high-fidelity

n-body model detailed in Equation (

3), which incorporates the gravitational effects of Earth, Moon, and Sun. The dynamics equations are integrated using the following key implementation features:

Integration scheme. MATLAB’s ode45 solver with RelTol =

and AbsTol =

, ensuring numerical accuracy over extended 50–150 day arcs.The propagation follows a segmented approach, where each arc is integrated separately. Specifically, the final state of the

i-th arc defines the initial position for the subsequent segment, while the velocity is updated by the impulsive maneuver

before the next integration call. For details, consult

https://www.mathworks.com/help/matlab/ref/ode45.html (accessed on 20 December 2025).

Reference frame. All states and ephemerides are expressed in the Earth–Centered Inertial J2000 frame (also referred to as EME2000 in SPICE, [

10]), with origin at Earth’s center of mass and axes fixed with respect to the mean equator and equinox at epoch J2000. The

X–axis points toward the mean vernal equinox of J2000, the

Z–axis aligns with Earth’s mean rotation axis at J2000, and the

Y–axis completes a right–handed triad in the equatorial plane. This realization is quasi–inertial and consistent with the ICRF at the J2000 epoch to first order, making it appropriate for high–precision orbital propagation over mission timescales considered here. SPICE kernels are queried explicitly in the ‘J2000’ inertial frame, and no transformations to rotating Earth–fixed frames are applied during numerical integration.

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the ECI J2000 frame.

Time normalization. Time normalization is a numerical technique that improves solver performance by re-scaling the optimization variables. Instead of working with physical arc durations in seconds, the optimizer manipulates a dimensionless variable , where the two are related by a characteristic time constant T via .

This model captures third-body perturbations and provides a robust foundation for both global GA sampling and local SQP refinement, ensuring that optimized trajectories remain valid under realistic dynamical conditions.

4.1. Case Study: A Cargo Mission

This case study investigates a low-energy transfer from a Low Earth Orbit to a Near-Rectilinear Halo Orbit. The scenario is modeled on the CAPSTONE mission profile [

6] and applies the characteristics of an uncrewed cargo vehicle. The trajectory leverages a weak-stability-boundary (WSB) transfer to minimize propulsive cost over a mission duration of 120–150 days. The entire transfer is partitioned into multiple arcs, corresponding to

nodes.

admissible impulsive maneuvers are considered; the segment durations are parameterized by normalized variables

scaled by a 50-day reference to promote well-conditioned timings in the optimizer. The decision vector comprises the three components of each

and

, while the optimization criterion is the minimization of the total impulse defined by (

6).

The constraint set encodes feasibility and WSB geometry: minimum geocentric altitude in the corridor , arrival inclination , Earth-centered apogee distance , and characteristic energy at departure . Additional safety margins enforce a minimum Earth–Moon clearance along the arc and exclude hyperbolic Earth escape at perigee. These bounds are applied in normalized form within the NLP to balance constraint scales and improve convergence.

Global exploration uses a genetic algorithm to sample the highly nonconvex landscape and identify near-feasible guesses that exhibit high-apogee shaping and soft lunar approach consistent with the WSB capture. The GA fitness augments the total with smooth penalties for constraint deviations, discouraging segment collapse and favoring admissible apogee and windows. Local refinement adopts SQP with analytic first derivatives; feasibility is driven below prescribed tolerances while redistributing maneuver effort and segment durations to improve the .

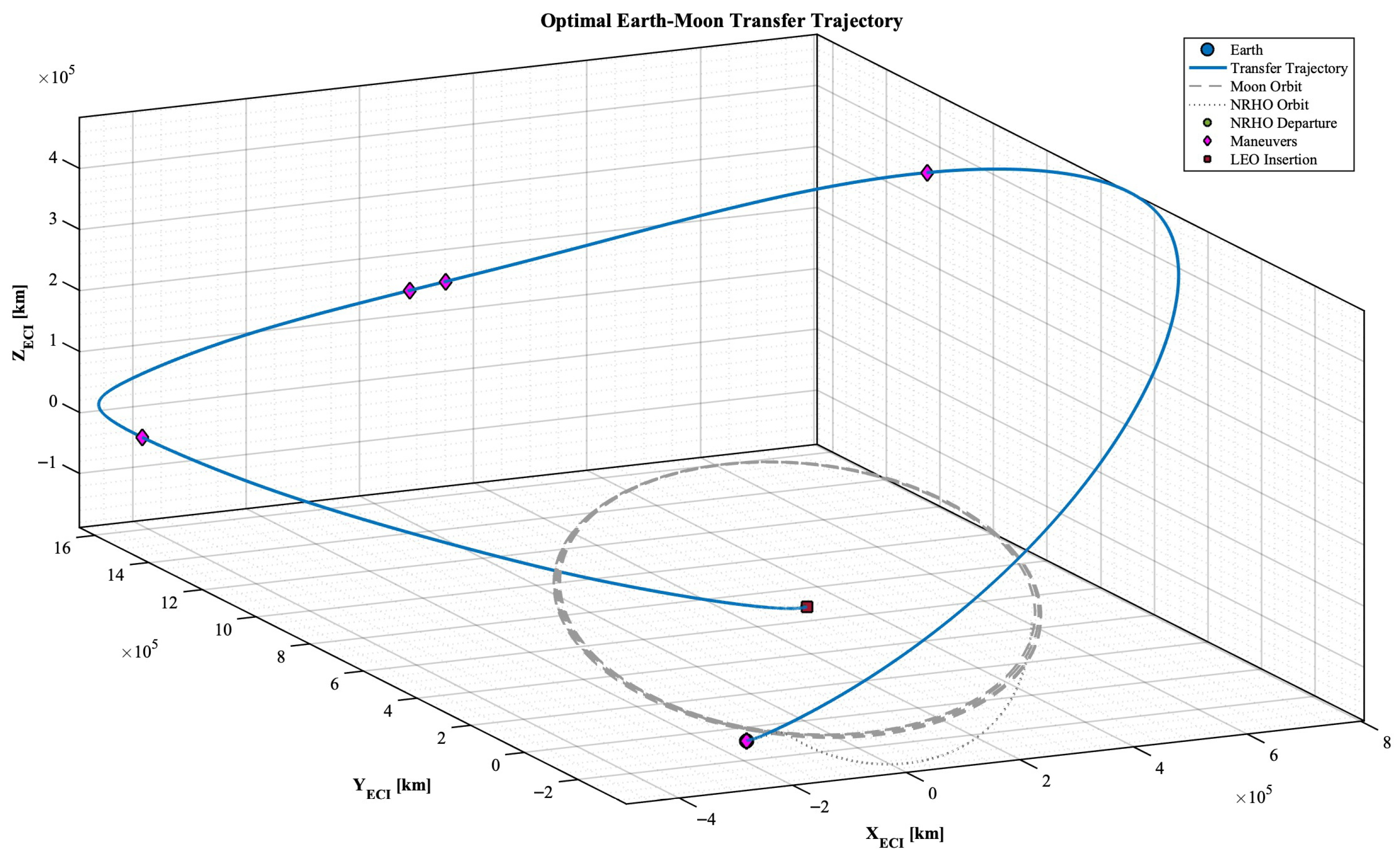

Representative solutions produced by the GA → SQP process exhibit:

- i

An apogee near 1.3 × km, where solar perturbations shape the inertial ellipse;

- ii

A gradual Earth departure satisfying the range;

- iii

A low-energy lunar arrival that meets the target inclination corridor;

- iv

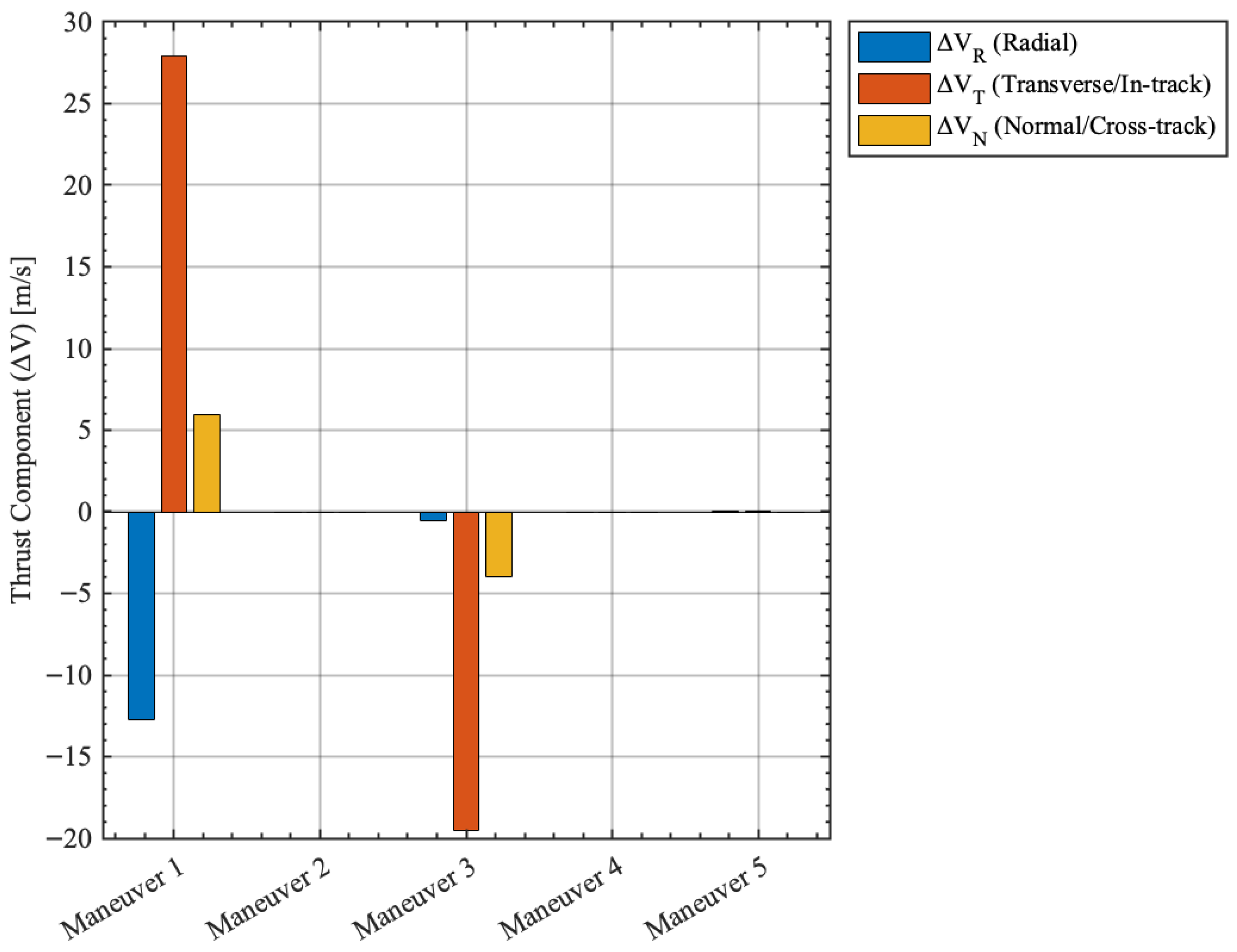

The optimal thrust profile is characterized by a sequence of major propulsive burns concentrated at the initial perigee and on the pre-apogee segment of the trajectory, concluding with low-magnitude maneuvers for terminal phase correction.

The refined trajectories maintain altitude and Moon-proximity margins, while reducing the total relative to GA guesses, with maneuver count and placement consistent with the multiple-shooting design.

Vehicle-level constraints. In addition to the geometric and trajectory feasibility constraints, the NLP formulation incorporates a set of vehicle-specific performance limits derived from the spacecraft platform used for the cargo mission [

1]. These bounds reflect the system’s operational capabilities, such as its total mass budget and propulsion performance. These limits are implemented in the optimization problem as normalized inequality constraints (the relevant numerical values are strictly confidential).

Mass budget and propellant usage. The initial mass of the spacecraft, , is the sum of its dry mass (), propellant mass (), and payload mass (). The usable propellant is bounded by , and the final mass, , must be greater than or equal to the dry mass plus the payload mass. Propellant consumption for each maneuver is linked to the velocity change, , via Tsiolkovsky’s rocket equation: , where is the effective exhaust velocity (a function of the specific impulse and standard gravity ), and and are the spacecraft masses just before and after the i-th burn, respectively.

Thrust and acceleration limits. The thrust magnitude, , produced during each burn must be within the engine’s operational range, i.e., . This, in turn, limits the acceleration that the spacecraft can achieve, as the thrust acceleration magnitude, , must not exceed a maximum value, .

Operational constraints. Several practical mission rules are enforced. These include a maximum number of engine burns (at most N), a minimum time interval between consecutive burns, and bounds on the duration of each coasting segment, . Additional constraints can also be placed on the total number of engine restarts, the allowable windows for thrusting (duty cycles).

Power and thermal margins. For the selected propulsion technology, the steady-state thrust and the cumulative burn time must respect the available power from the solar panels and the thermal limits of the engine system to prevent overheating.

These vehicle-level constraints are applied in normalized form within and are active in both stages: as penalty terms in the GA composite fitness and as explicit constraints in the SQP refinement.

Our case study yields several key insights into the optimization strategy. First, enforcing constraints on the apogee altitude and departure energy () effectively guides the search towards low-energy corridors, enabling significant propellant savings at the cost of an extended transfer duration.

Finally, the analysis reveals a sensitivity to both the departure epoch and the insertion point in the NRHO. This suggests that a purely local optimization from a single guess may not be sufficient. A more robust approach would involve initiating a series of local optimizations (a multi-start approach) from slightly varied initial conditions centered around a promising GA solution. Furthermore, before finalizing a trajectory, its robustness should be validated by introducing small perturbations to the segment times and maneuver epochs to ensure the solution remains stable and feasible.

4.2. Global Optimization Search

Solver configuration. All solver options were kept at their MATLAB R2024a defaults, except PopulationSize and Generations , which were set respectively to achieve convergence within the desired runtime budget (all other operators and tolerances remain at the default values as per MathWorks documentation). It is important to note that the algorithm performs well without the need of tuning its parameters, highlighting the flexibility of the proposed approach. The relevant GA parameters are listed here.

PopulationSize: 50; Generations: 250;

CreationFcn (default): gacreationuniform or gacreationlinearfeasible depending on presence of linear constraints;

CrossoverFcn (default): crossoverscattered; CrossoverFraction ;

MutationFcn (default): mutationgaussian (unconstrained) or mutationadaptfeasible (constrained);

SelectionFcn (default): selectionstochunif; FitnessScalingFcn (default): fitscalingrank;

Termination (default): FunctionTolerance and MaxStallGenerations criteria; also FitnessLimit if set;

ConstraintTolerance (default): .

The implementation was carried out in MATLAB R2024a, utilizing the Global Optimization Toolbox and the Parallel Computing Toolbox. With this setup, the GA runtime is approximately 5 min on a workstation equipped with a 24-core Intel Core i9 processor and 32 GB of RAM.

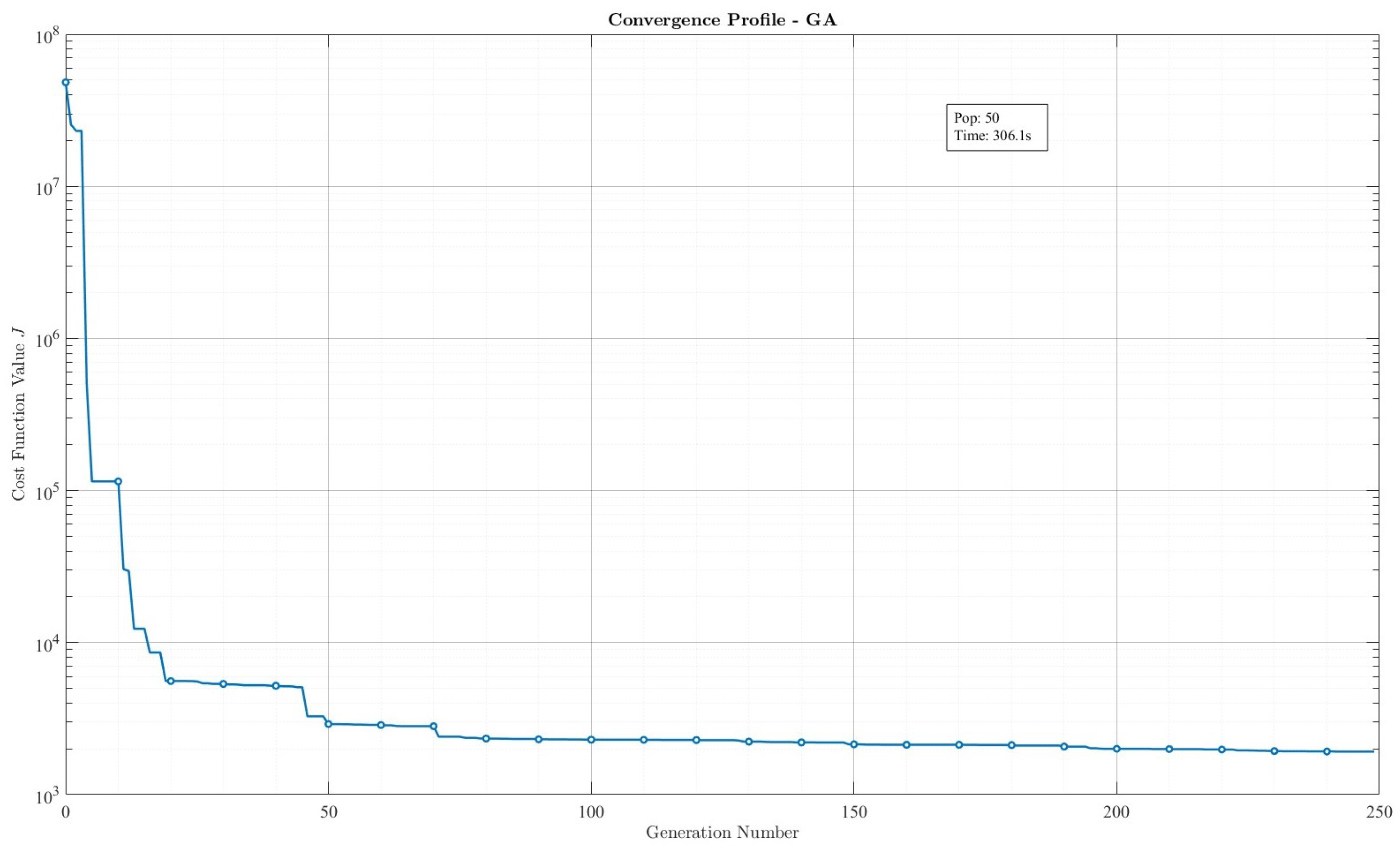

Constraint satisfaction and physical consistency. The typical evolution of the performance index during a GA run is shown in

Figure 2; multiple GA runs provide very similar results and trajectories.The selected GA solution satisfies the mission feasibility constraints (altitude range, arrival inclination,

, apogee, safety margins, temporal regularity) within the prescribed normalized tolerances

, as evaluated along the backward-propagated trajectory. Dynamics compliance is ensured by construction: the same segment-by-segment

n-body backward propagator (Earth–Moon–Sun) is used to evaluate the objective and all constraints; propellant usage and mass flow are consistent with thrust/

where applicable.

The resulting trajectory is illustrated in

Figure 3 and the maneuver timeline (impulse magnitudes and epochs) in

Figure 4.

4.3. Local Optimization Search

Warm start: Best GA candidate;

Gradients: Analytic gradients for and all constraints; variable/constraint scaling enabled;

Hessian: Reduced-memory BFGS update of the Lagrangian;

Line search and merit: Backtracking line search with -merit function and adaptive penalty multipliers;

Tolerances: Feasibility , optimality ; maximum iterations ; step-length safeguards ;

Variable bounds: Same box limits on and as in the GA stage;

Propagation: Identical backward “black-box” n-body propagator per segment (N − 1 loops), which relies on the MATLAB R2024a ode45 solver for numerical integration, ensuring model consistency across stages.

The SQP refinement was performed using the SNOPT solver within MATLAB R2024a. The Parallel Computing Toolbox was employed to execute multiple optimizations in parallel (via parfor) starting from the GA candidates. With this setup, the runtime is approximately 1 h on a workstation equipped with a 24-core Intel Core i9 processor and 32 GB of RAM.

Constraint satisfaction and physical consistency. All inequality constraints are satisfied within feasibility tolerance

by the refined solution; trajectory metrics computed via the same backward propagation confirm compliance with mission geometry and safety margins. The refined solution achieves an additional reduction in total

relative to the GA guess (approximately

, decreasing from

m/s to

m/s of the SQP solution), demonstrating a substantial enhancement in propellant efficiency compared to the preliminary solution. Furthermore, this final cost aligns with the operational baseline established by the CAPSTONE mission [

6], confirming the validity of the obtained trajectory. The refined trajectory is depicted in

Figure 5 and the refined maneuver timeline in

Figure 6.

Efficiency, robustness, and computational limitations. The adopted hybrid GA-SQP strategy constitutes a robust and efficient approach for solving the non-convex optimization problem, capitalizing on the respective strengths of the global and local search paradigms employed. The main feature are listed below.

Efficiency. The strategy’s efficiency arises from a structured handover between optimization paradigms. The GA performs the initial (computationally intensive) global exploration, but is terminated once it has successfully identified a promising basin of attraction. This prevents diminishing returns from applying random search as it nears a local optimum. The SQP method then takes over, using the GA’s output as a high-quality initial guess. Using analytic gradients and its inherent quadratic convergence properties, the SQP algorithm performs the final high-precision refinement efficiently, drastically reducing the overall computational cost compared to a standalone global search.

Robustness. The stochastic, population-based nature of the GA provides inherent robustness. By exploring the solution space in parallel from many different starting points, it effectively mitigates the risk of the local optimizer getting trapped in a poor local minimum, which is a significant danger in multi-body problems. The GA’s ability to handle non-smooth penalty functions and large, disconnected feasible regions makes it suitable for finding the “right” corridor for the WSB transfer, a task where gradient-based methods would likely fail without a good initial guess.

Computational limitations. Despite its strengths, the computational framework is not without limitations: these aspects are highlighted below.

- −

Parameter Tuning. The performance of the GA is sensitive to the choice of its parameters (population size, mutation/crossover rates) and the weighting of the penalty functions. Inappropriate tuning can lead to premature convergence or an overly slow exploration of the search space. A degree of problem-specific calibration is required to achieve the best results.

- −

Dimensionality. The computational cost, particularly for the GA, scales with the dimension of the decision vector (i.e., the number of shooting nodes, N). While parallelization of fitness evaluations can offset this, problems with a high number of nodes may become computationally prohibitive for the global search stage.

- −

SQP Convergence Issues. While robust, the SQP solution stage can still encounter difficulties. If the initial guess provided by the GA is on the edge of a highly non-linear or ill-conditioned region of the constraint manifold, the local optimizer may struggle to converge or may fail to find a feasible point.