Image-Based Segmentation of Hydrogen Bubbles in Alkaline Electrolysis: A Comparison Between Ilastik and U-Net

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Image acquisition: High-speed cameras can capture bubble nucleation, growth, and detachment at the cathode surface during alkaline electrolysis. The resulting datasets consist of time-resolved frames, requiring automated processing pipelines for analysis.

- Pre-processing: This stage aims to improve bubble visibility and prepare images for the segmentation stage. Image noise reduction and contrast improvement are achieved through filters such as Gaussian blur, median filtering, and histogram equalization.

- Segmentation: Classical approaches include thresholding (Otsu’s method) and edge detection algorithms. Recently, deep learning architectures such as U-Net, Ilastik, Mask R-CNN, and DeepLab have been employed to achieve accurate bubble boundary detection in complex illumination and overlapping bubble conditions.

- Feature extraction: After segmentation, bubble properties can be quantified using specific libraries, including area and equivalent diameter, shape descriptors like aspect ratio and circularity, and detachment frequency and growth rate.

- Tracking and dynamics analysis: Algorithms such as optical flow, Kalman filtering, and centroid tracking allow reconstruction of bubble trajectories and detachment events over time. These analyses connect bubble dynamics to electrode overpotential and overall cell efficiency.

- Automation and scalability: Machine learning pipelines implemented in Python v. 3.14.0 (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow, Scikit-learn) enable automated classification of bubble behaviors, reducing manual intervention and ensuring reproducibility across large datasets.

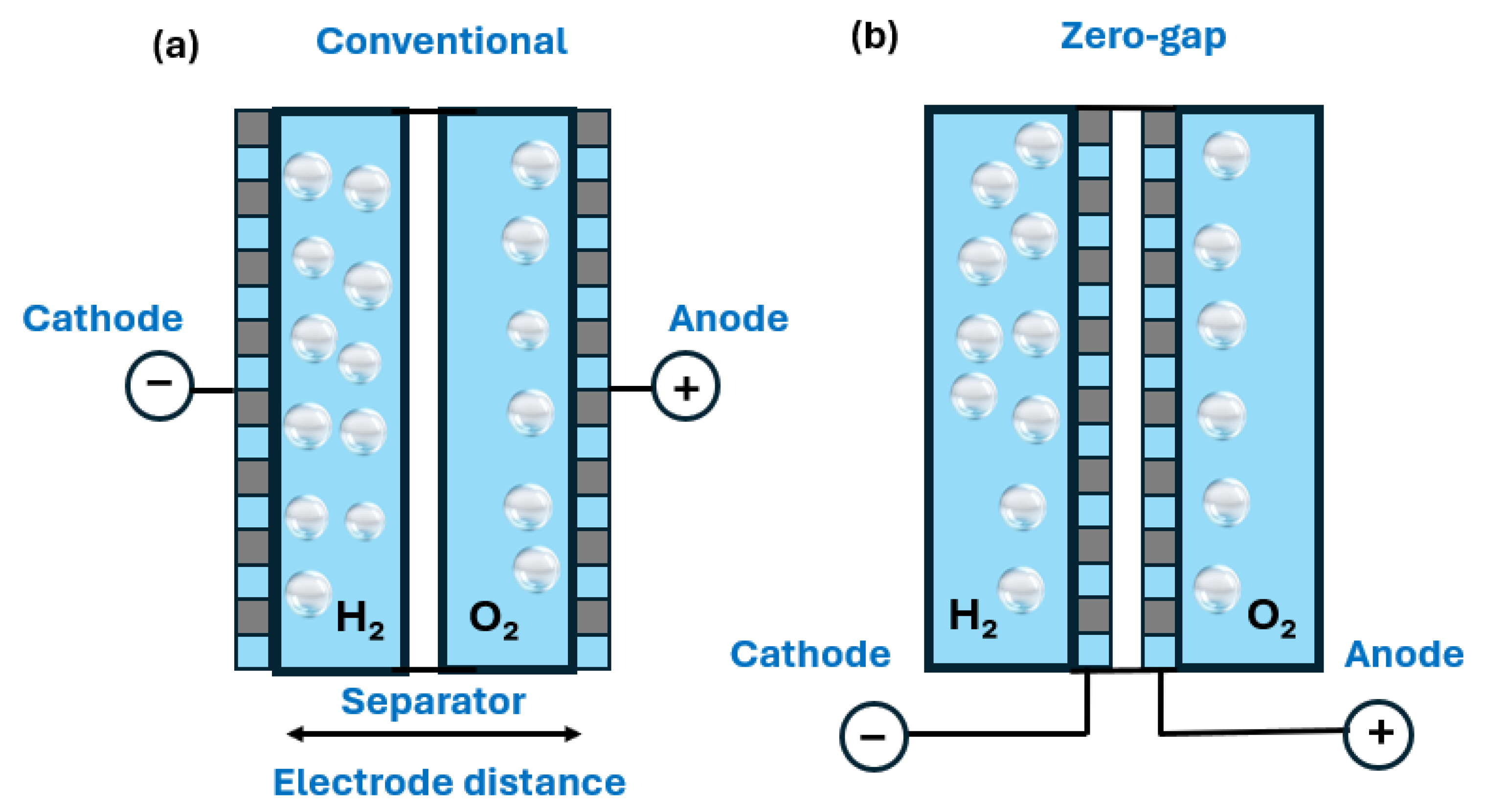

2. Principles of Water Electrolysis

- At the cathode, a reduction reaction takes place, where electrons are gained:

- At the anode, an oxidation reaction occurs, involving the loss of electrons:

- and are the equilibrium potentials of the redox couples H+/H2 and O2/H2O, respectively.

- and are their corresponding overpotentials.

- i is the current intensity;

- Δt is the electrolysis duration;

- N is the number of electrons exchanged (equal to 2 for hydrogen formation at the cathode);

- F is the Faraday’s constant.

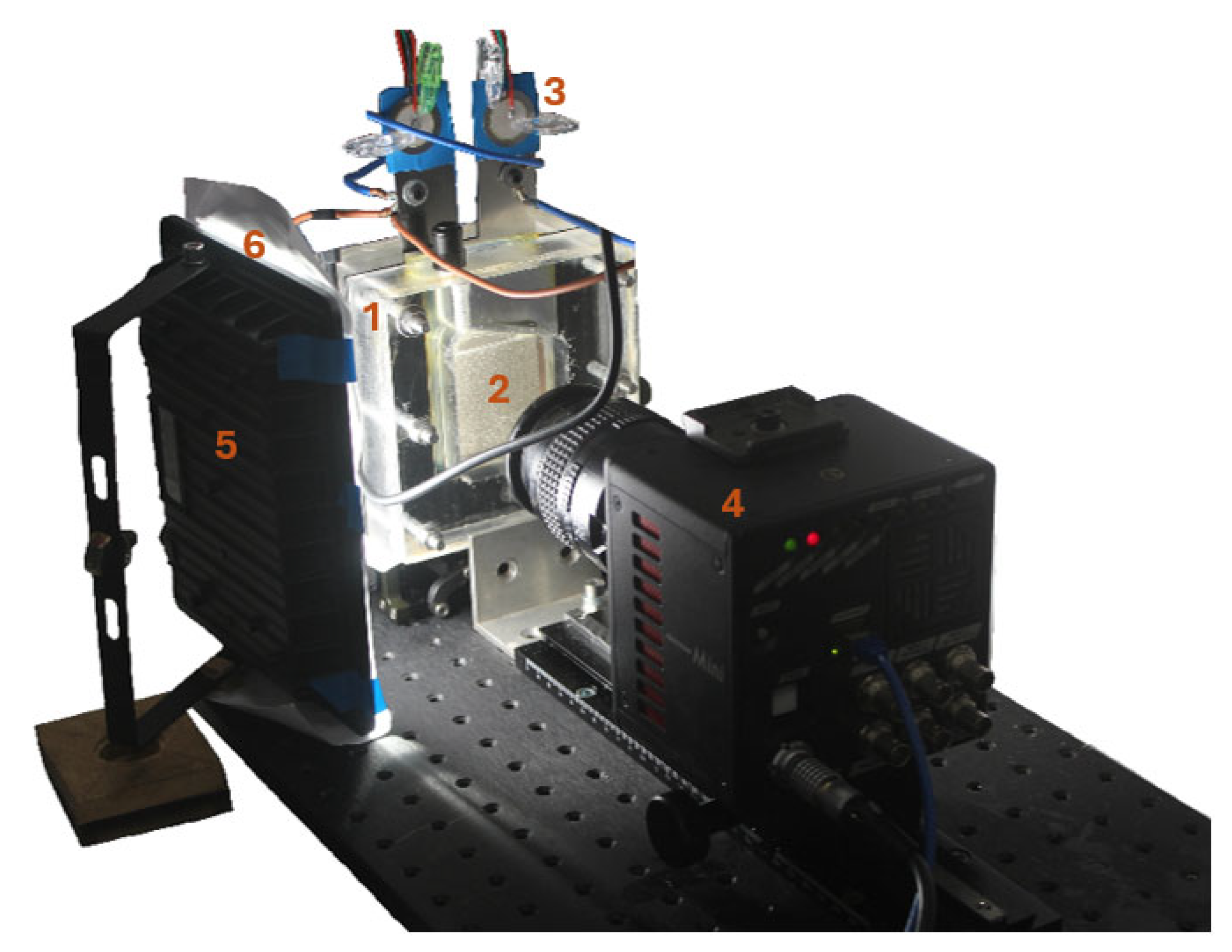

3. Experimental Setup

4. Experimental Protocol

4.1. Electrolysis Observation

- Two porous nickel electrodes.

- A potassium hydroxide (KOH) electrolyte.

- A current generator.

- A voltmeter measuring the potential difference between electrodes and a second voltmeter measuring the voltage across a cable, allowing precise calculation of current intensity through using Ohm’s law.

- A high-speed camera connected to a PC for image acquisition.

- Percuss the electrode surface to release residual bubbles from previous tests.

- Set the current intensity to the desired value.

- Wait two minutes to allow stabilization.

- Record the cathode region using the high-speed camera.

4.2. Manual Determination of Bubbles Characteristics

5. Numerical Methods

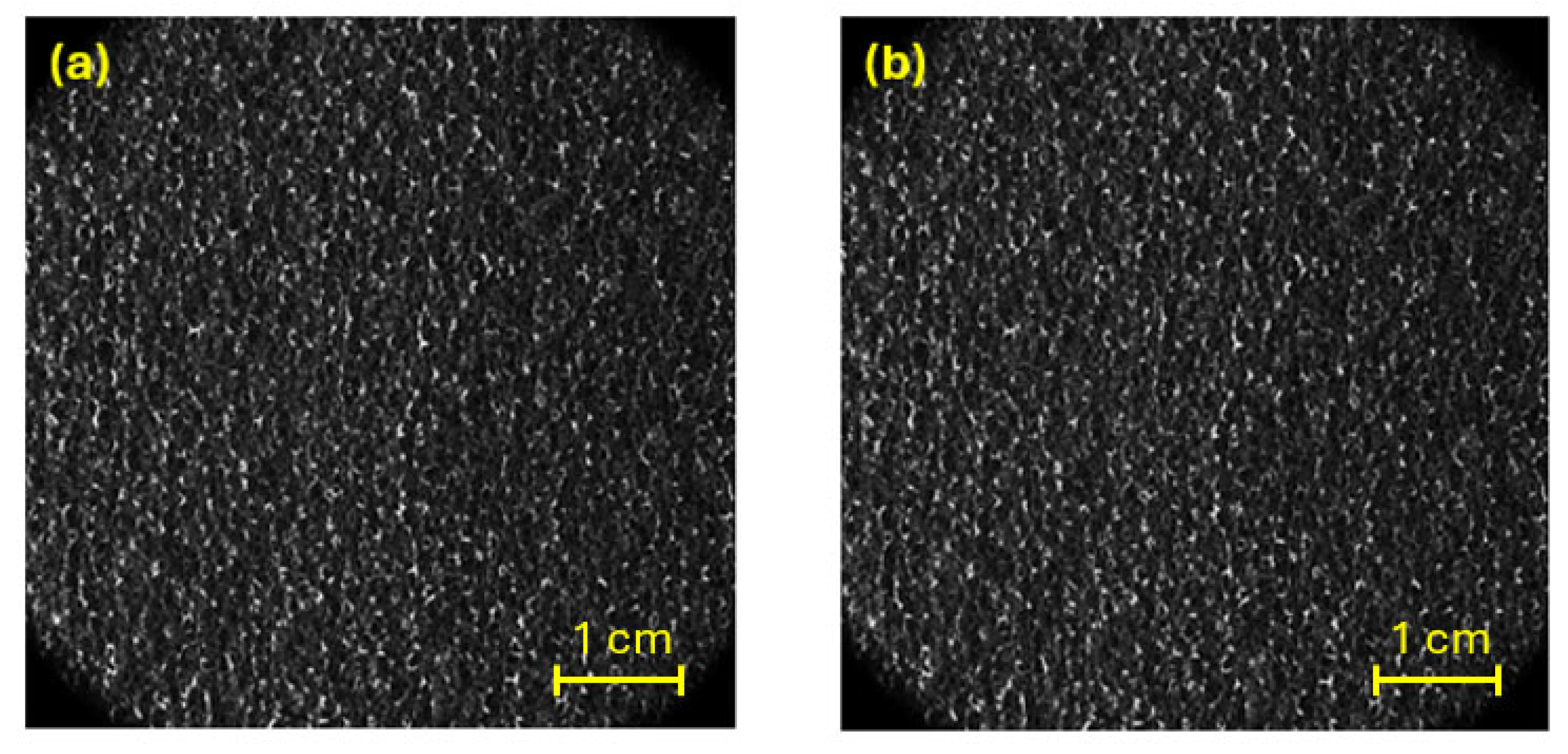

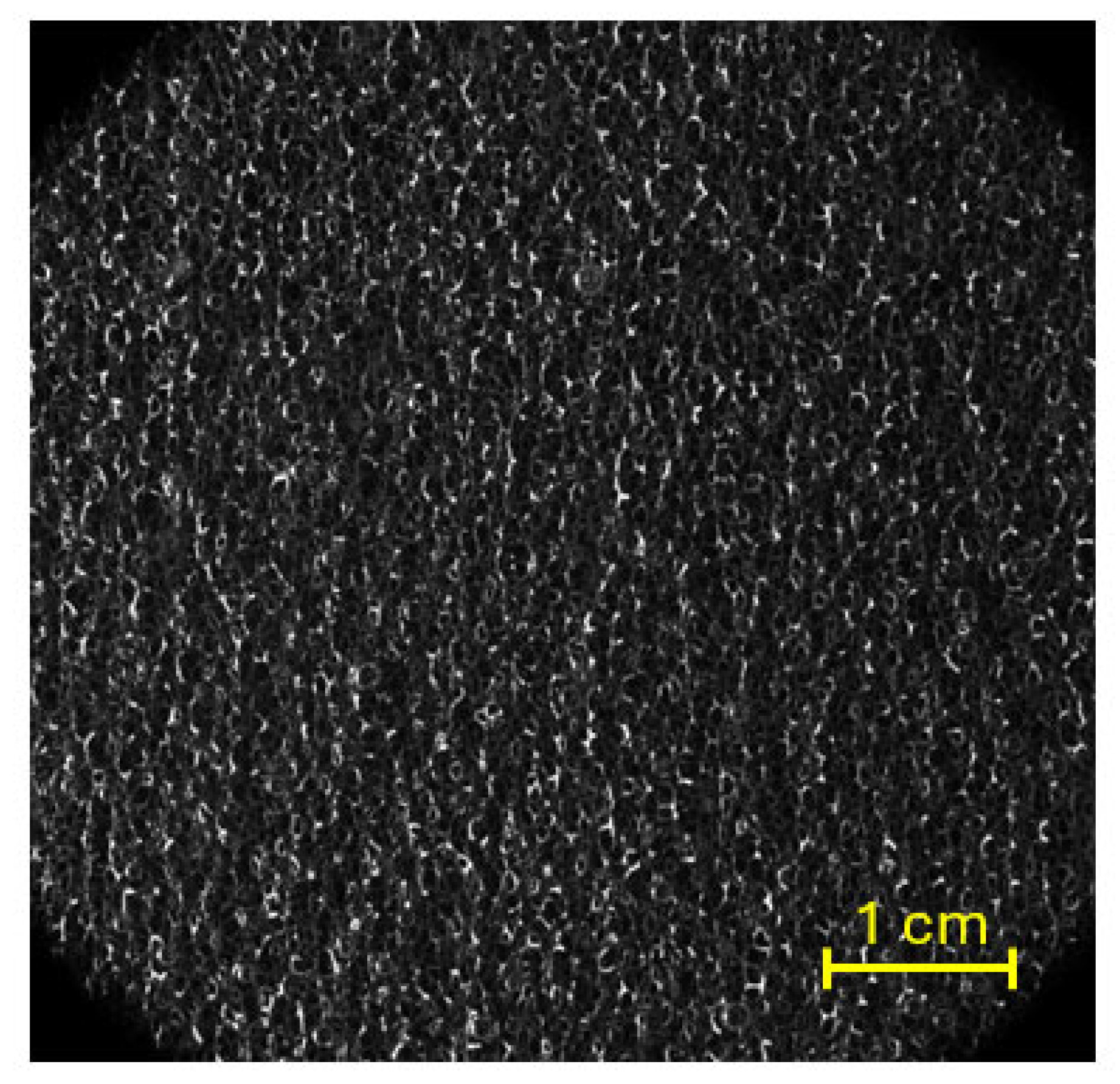

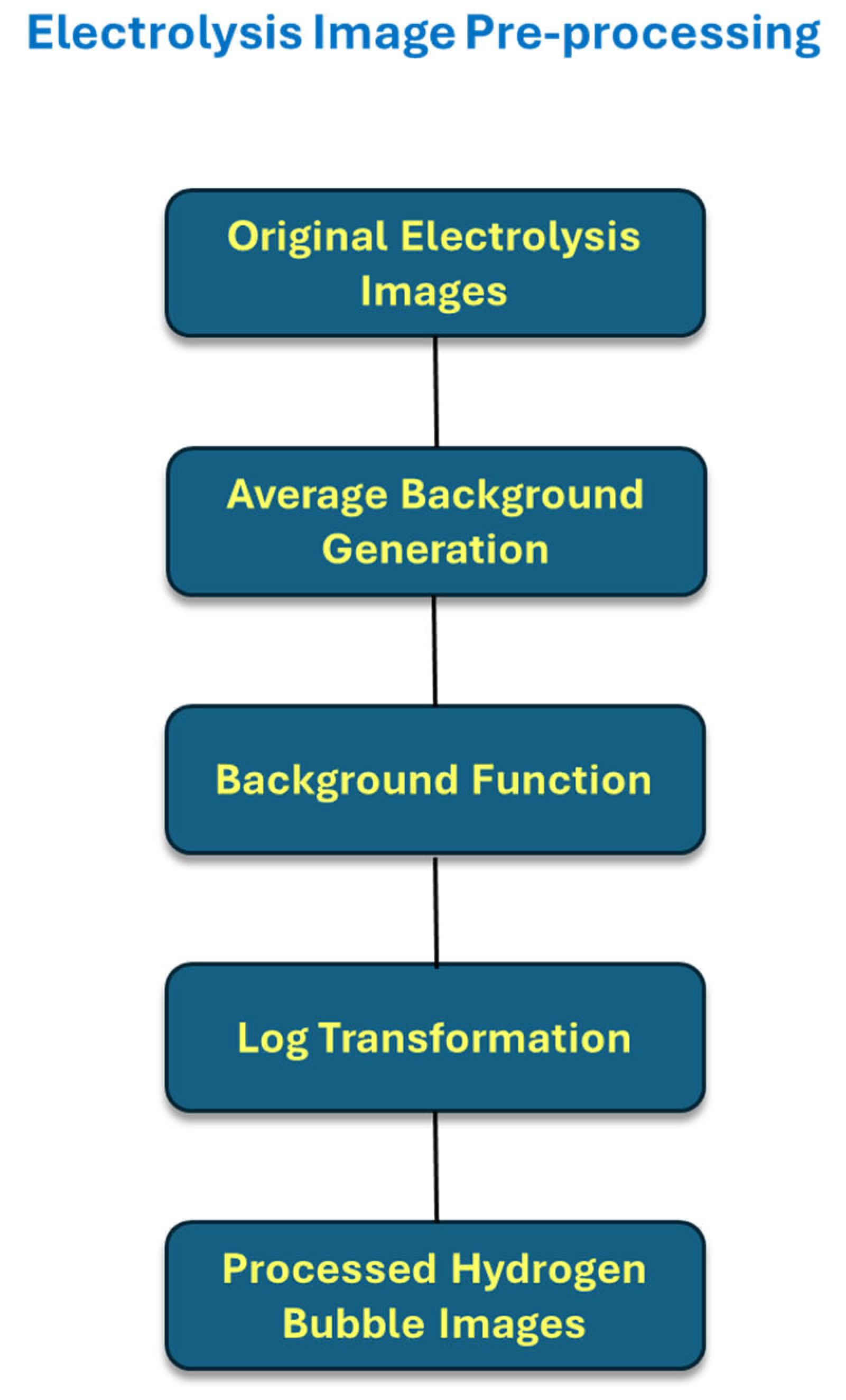

5.1. Image Pre-Treatment

- Reference window selection: 30 frames before and after each target frame were chosen.

- Mean image calculation: the pixel-wise average generated a static background.

- Background subtraction: isolating moving hydrogen bubbles.

- Logarithmic transformation: enhancing contrast for better contour detection.

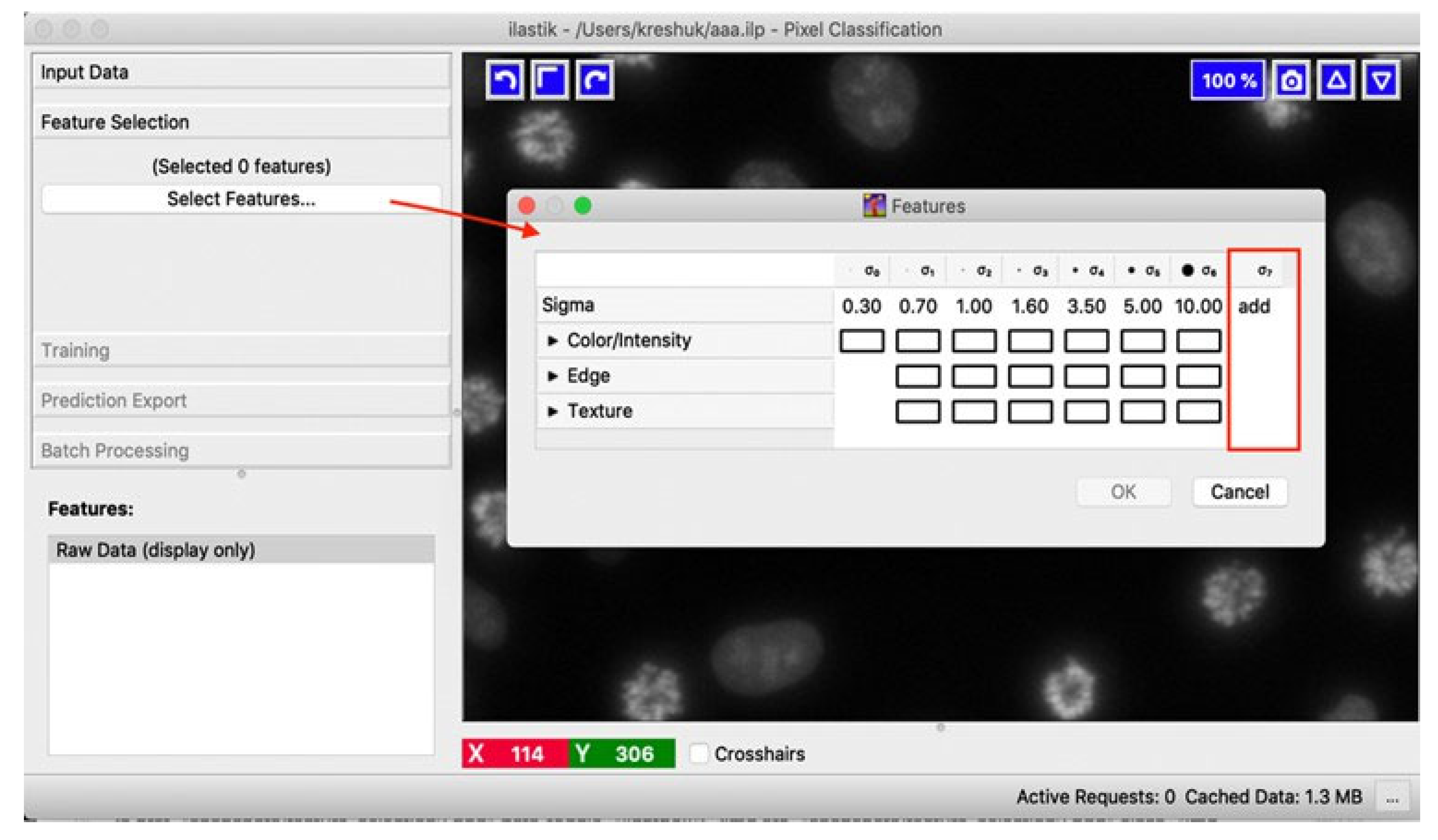

5.2. Ilastik Software

5.3. U-Net Model

5.3.1. Encoding

5.3.2. Decoding

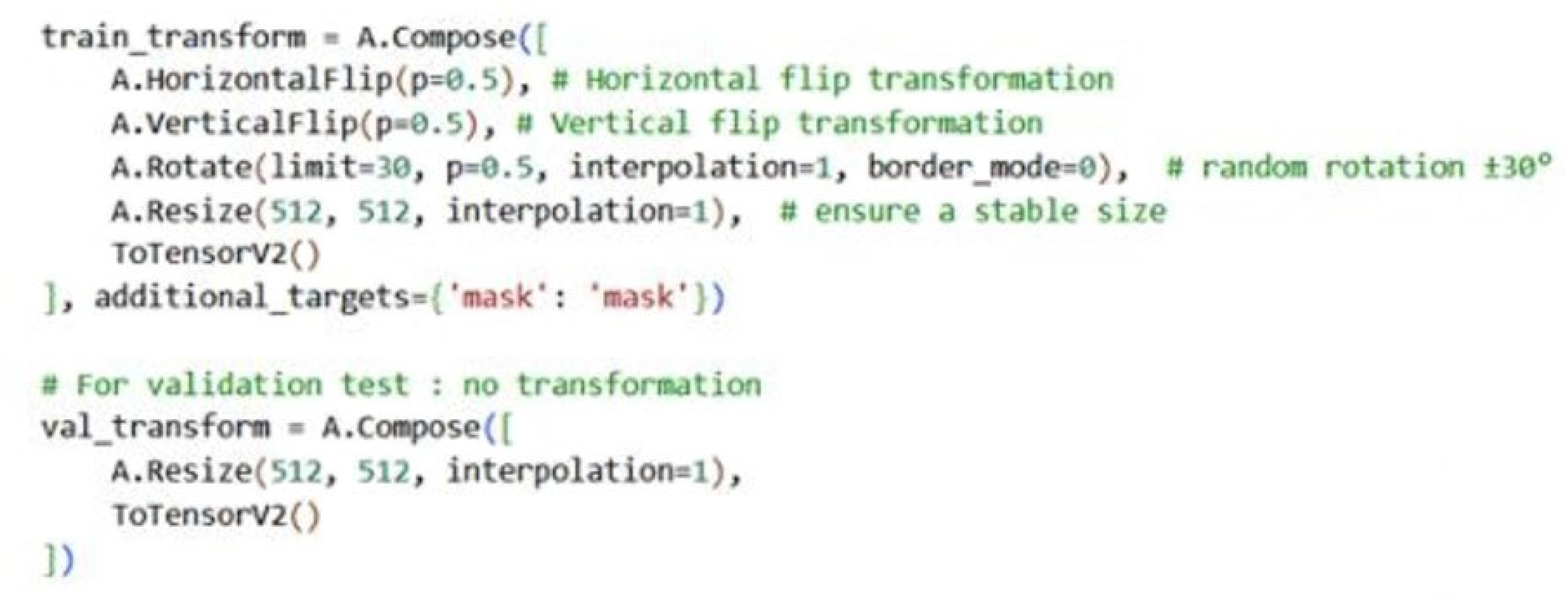

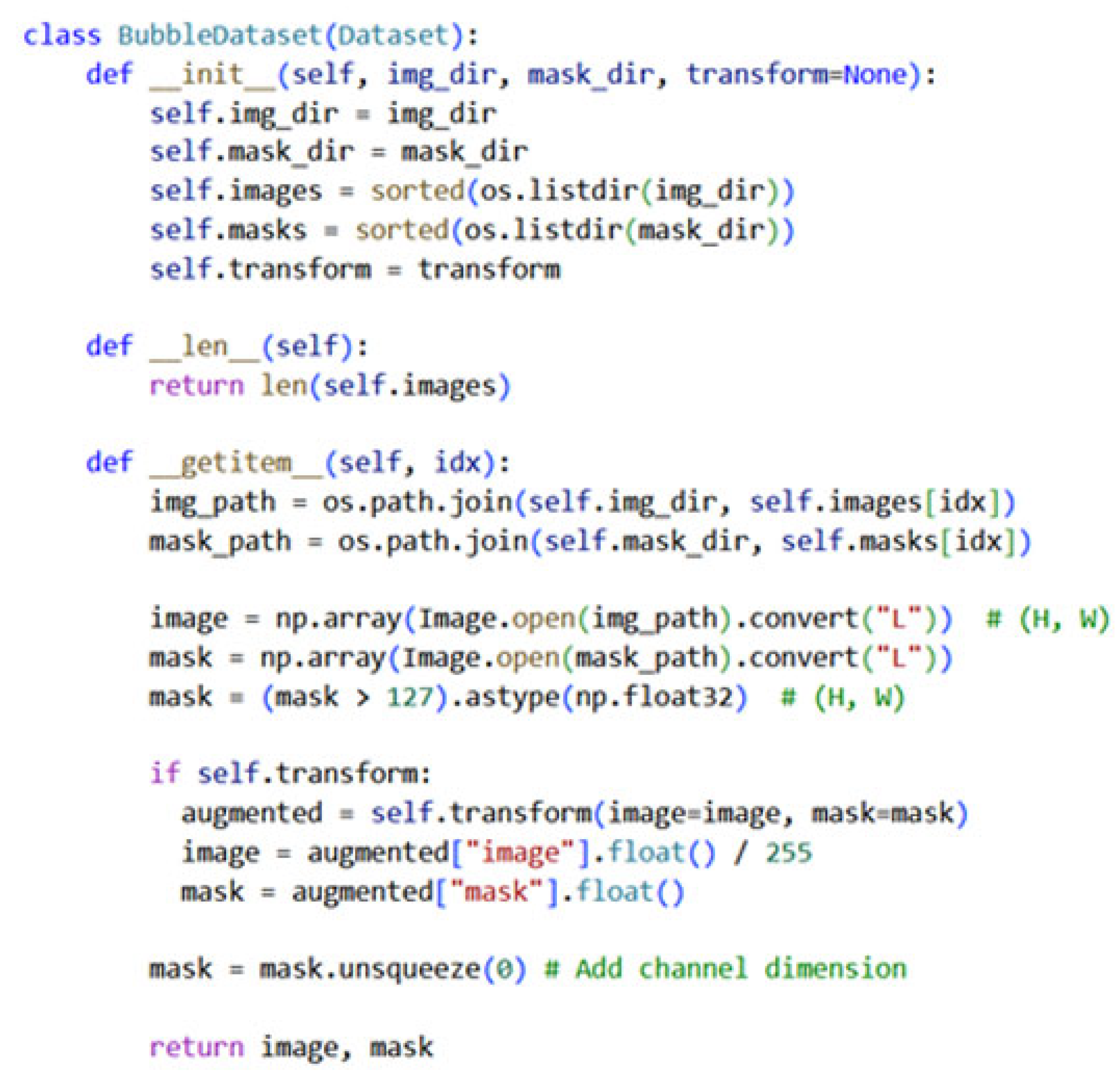

5.3.3. U-Net Implementation

- C is the number of channels corresponding to extracted features;

- H is the height (rows);

- W is the width (columns).

5.3.4. Implementation of Convolutional Layers and U-Net Architecture in PyTorch

5.3.5. Model Training Workflow in PyTorch

5.4. Fiji Software

Configuration and Operation of the TrackMate Plug-In

- Thresholding Detector

- LAP Tracker

- The maximum number of frames allowed between disconnections;

- The maximum spatial distance within which segments can still be linked.

6. Determination of the Size of Hydrogen Bubbles

- yi is the manually measured characteristic of the -th bubble;

- is the corresponding predicted characteristic;

- N is the total number of matched entities.

7. Determination of the Bubble Release Frequency

8. Implementation of a Tracking Data Exploration Tool

- Initial calibration—Bubbles detected in the first two frames were excluded to initialize the counter at zero. This step accounted for potential detection errors and ensured that no bubbles were considered before actual formation began.

- Minimum duration filter—Tracks lasting fewer than 20 frames were removed. This filter eliminated transient noise and artifacts, such as background reflections or residual elements unrelated to bubble formation.

- Vertical displacement filter—Bubbles with a vertical displacement (difference between maximum and minimum y-coordinates) smaller than 0.5 mm were discarded. This condition removed false positives associated with static bright spots or imperfections on the porous electrode.

- Initial position filter—Bubbles whose first appearance occurred below the 18.2 mm mark on the vertical axis (measured from top to bottom) were excluded. This ensured that only bubbles originating within the visible region of the electrode were counted, preventing those entering the frame from being included.

import pandas as pd- # Load TrackMate output CSV

- # Replace 'trackmate_data.csv' with your actual filename

- df = pd.read_csv('trackmate_data.csv')

- # Assumed column names — adjust if needed

- # 'Track ID', 'Frame', 'Y', 'X' are typical columns from TrackMate

- # Ensure 'Y' is in millimeters or convert if needed

- # Step 1: Remove bubbles present in the first two frames

- first_two_frames = df[df['Frame'] <= 2]['Track ID'].unique()

- df_filtered = df[~df['Track ID'].isin(first_two_frames)]

- # Step 2: Remove bubbles tracked in fewer than 20 frames

- track_counts = df_filtered['Track ID'].value_counts()

- valid_tracks = track_counts[track_counts >= 20].index

- df_filtered = df_filtered[df_filtered['Track ID'].isin(valid_tracks)]

- # Step 3: Remove bubbles with vertical displacement < 0.5 mm

- vertical_displacement = df_filtered.groupby('Track ID')['Y'].agg(['min', 'max'])

- vertical_displacement['delta'] = vertical_displacement['max'] - vertical_displacement['min']

- valid_tracks = vertical_displacement[vertical_displacement['delta'] > 0.5].index

- df_filtered = df_filtered[df_filtered['Track ID'].isin(valid_tracks)]

- # Step 4: Remove bubbles whose first appearance is below 18.2 mm

- first_positions = df_filtered.groupby('Track ID').apply(lambda g: g[g['Frame'] == g['Frame'].min()])

- valid_tracks = first_positions[first_positions['Y'] <= 18.2]['Track ID'].unique()

- df_filtered = df_filtered[df_filtered['Track ID'].isin(valid_tracks)]

- # Final count of bubbles that emerged from the electrode

- bubble_count = df_filtered['Track ID'].nunique()

- # Calculate release frequency per surface unit

- acquisition_time = 3.008 # seconds

- window_side_mm = 20.48

- window_area_mm2 = window_side_mm ** 2

- frequency_per_mm2 = bubble_count / window_area_mm2

- print(f"Number of bubbles detected: {bubble_count}")

- print(f"Bubble release frequency: {frequency_per_mm2:.3f} bubbles/mm2 over {acquisition_time} seconds")

9. Results

9.1. Predictions of Hydrogen Bubbles Dimensions

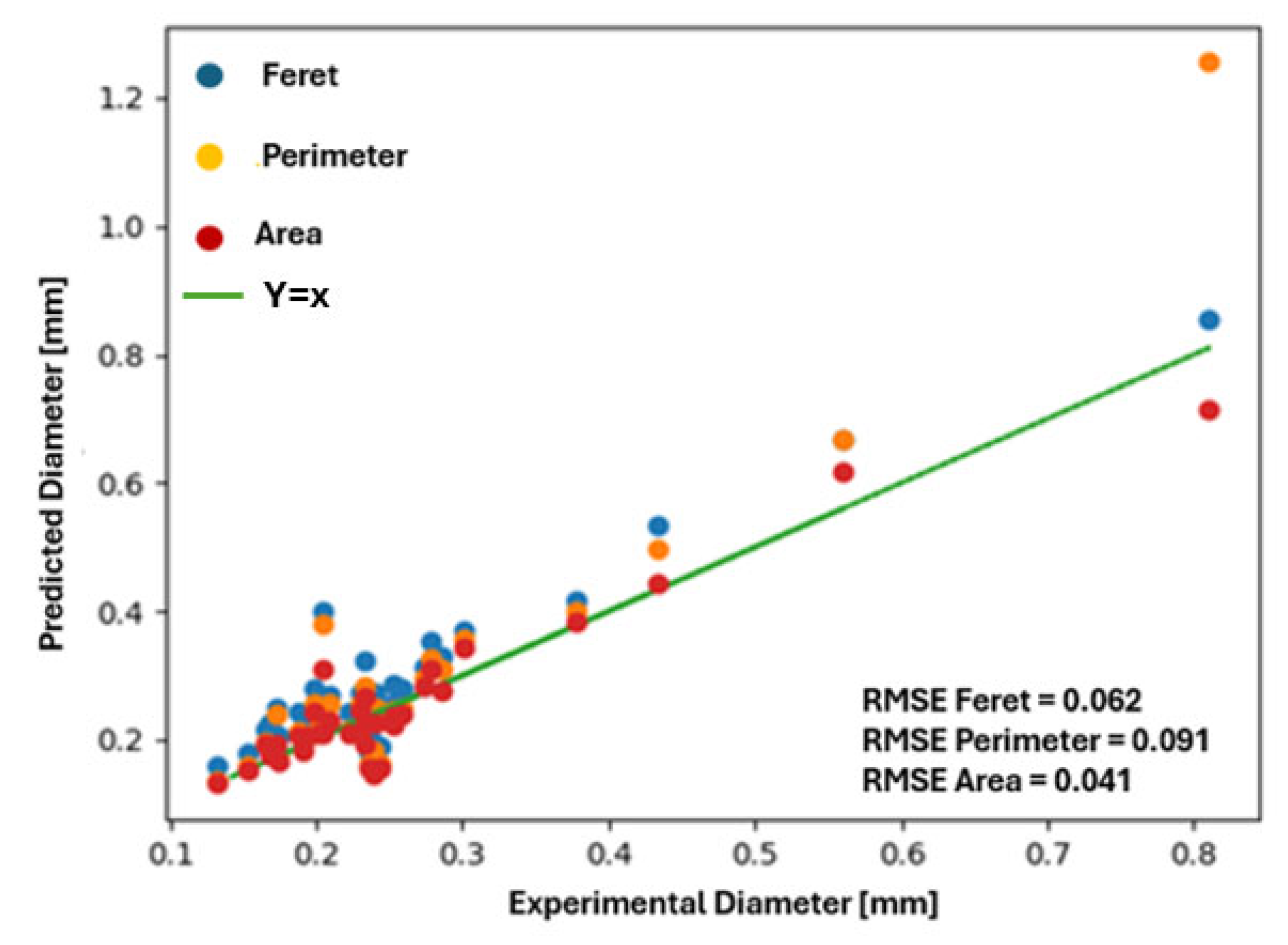

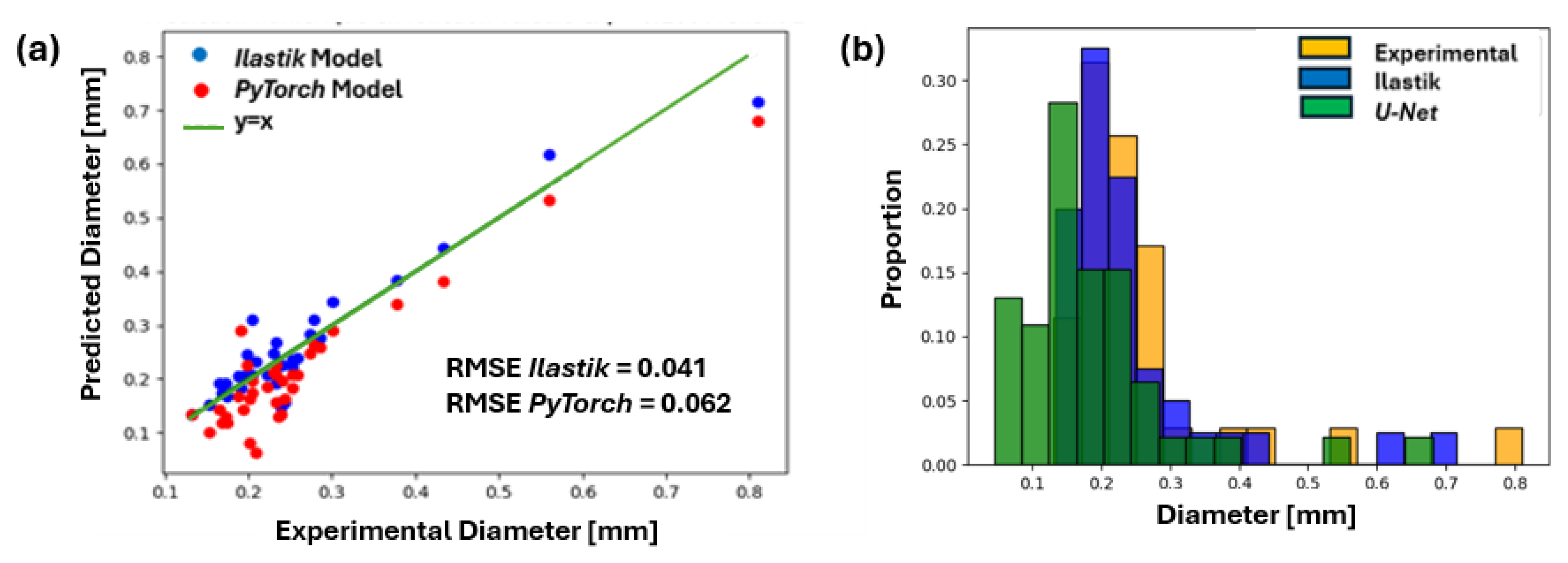

9.2. Predictions of the Ilastik Model

9.2.1. Presentation of Ilastik Results

9.2.2. Discussion of Ilastik Results

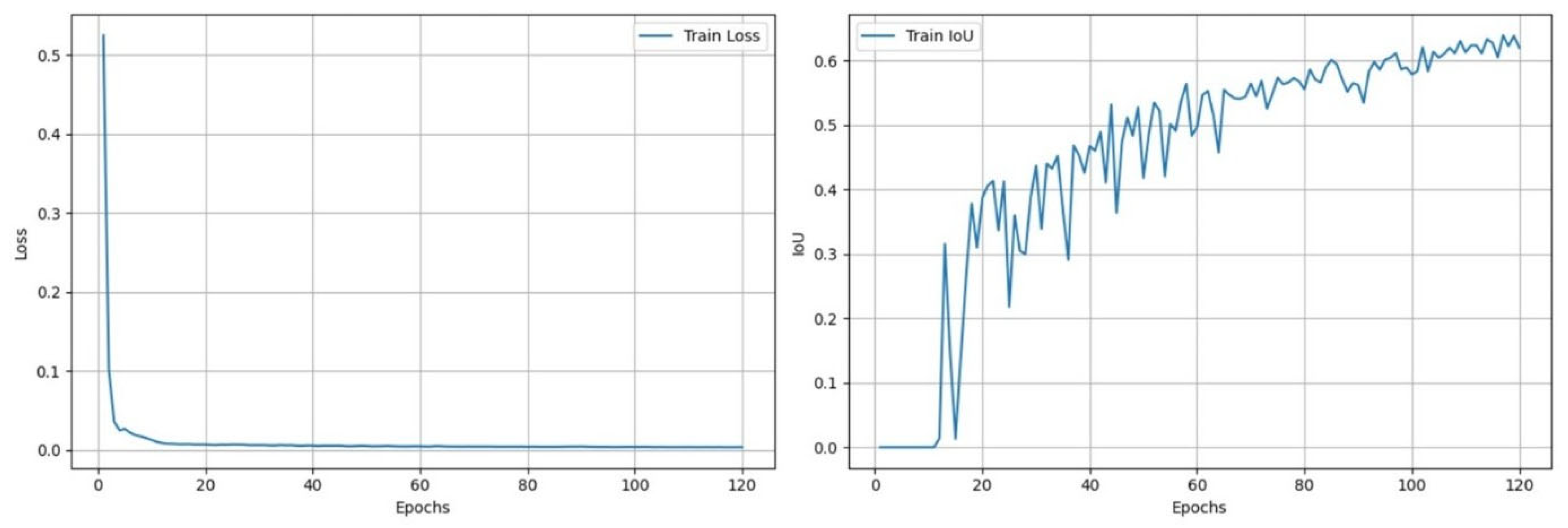

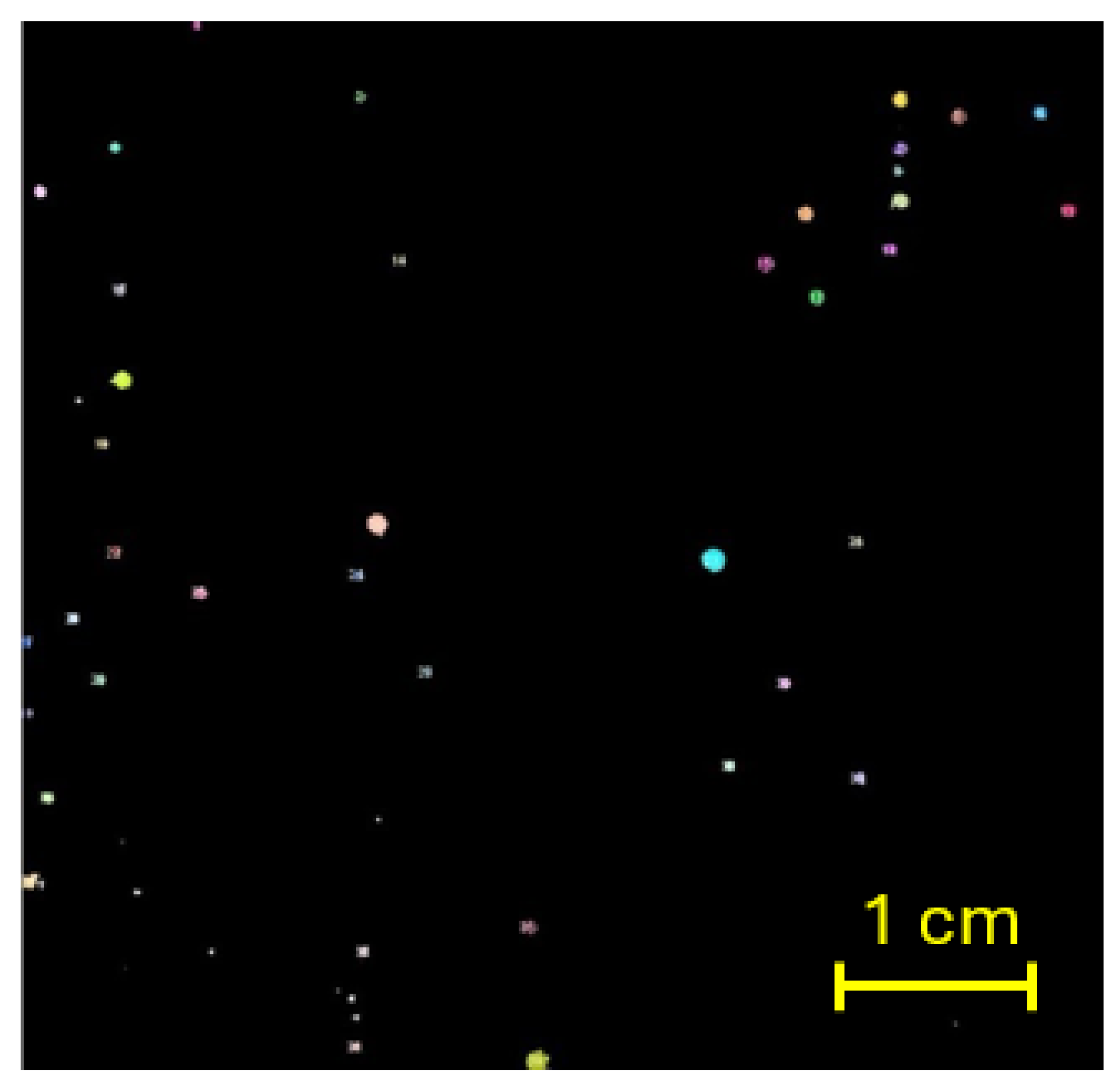

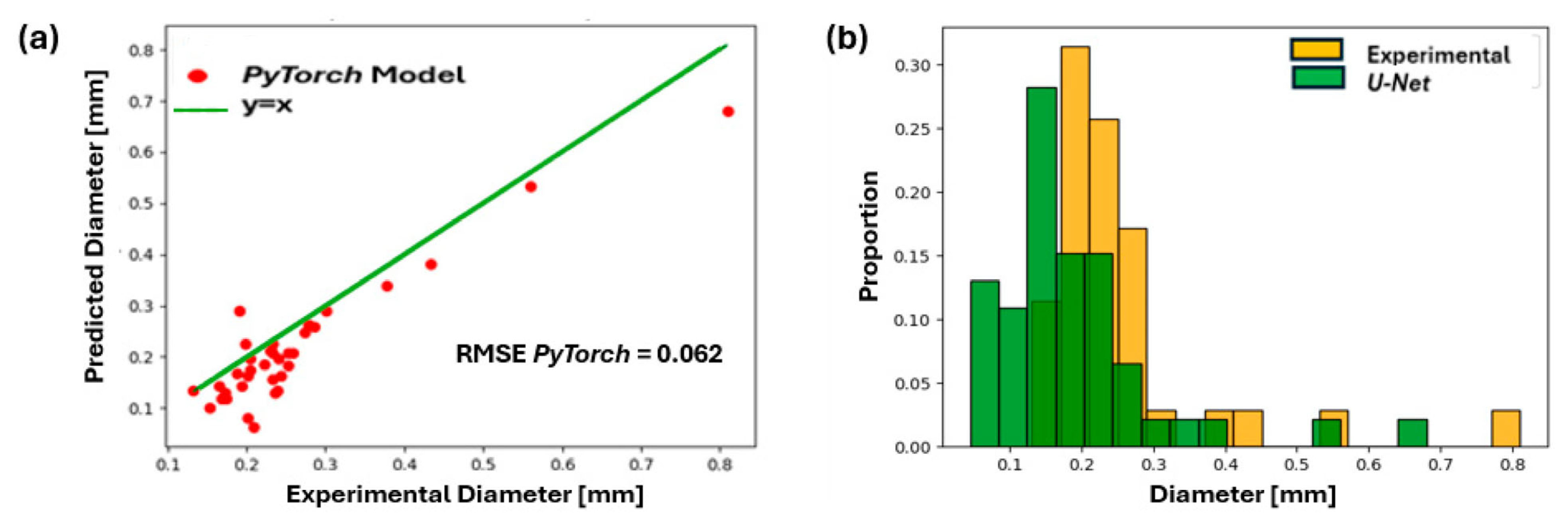

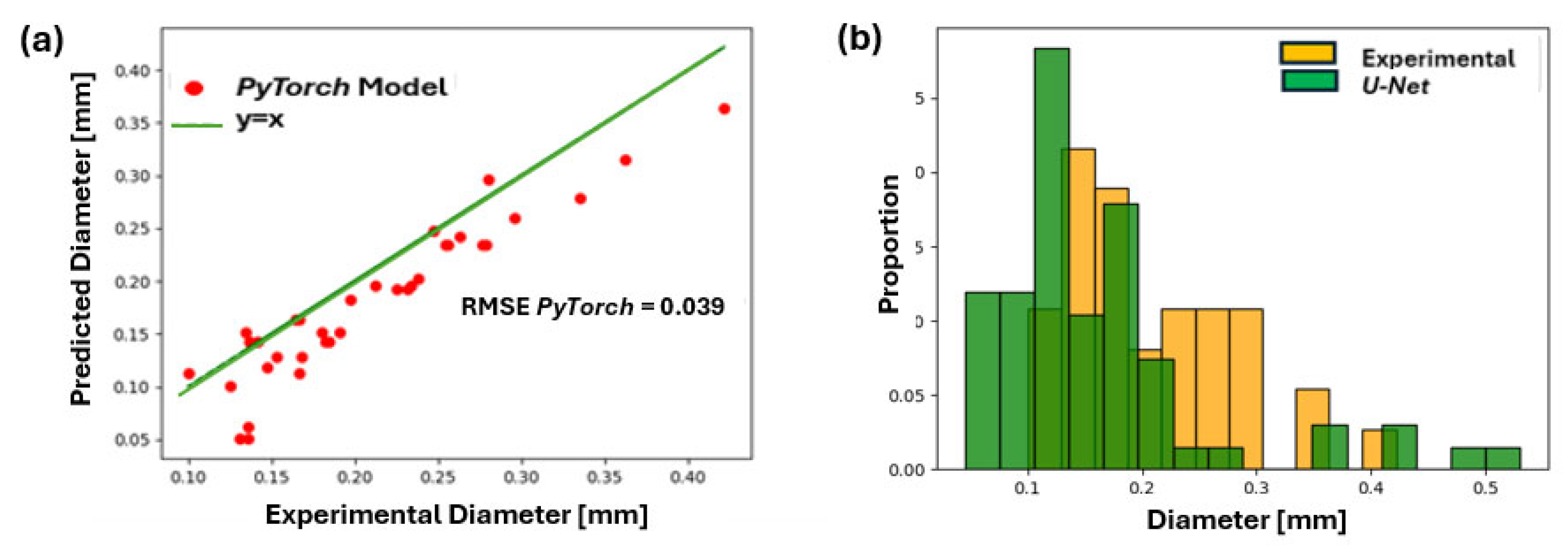

9.3. Predictions of the U-Net Model

9.3.1. Presentation of U-Net Results

9.3.2. Discussion of U-Net Results

9.4. Comparative Analysis of the Ilastik and U-Net Models

- Ilastik generally overestimates bubble diameters.

- U-Net generally underestimates bubble diameters.

- Main conclusions:

9.5. Predictions of the Hydrogen Bubble Release Frequencies Using the U-Net Model

9.5.1. Presentation of Results

9.5.2. Analysis of Results

- Even one missing bubble in a single frame forces TrackMate to initiate a new track.

- This artificially inflates bubble counts.

- Therefore, this disrupts the computed release frequency.

9.6. Discussion

9.6.1. Interpretation of the Segmentation Performance

9.6.2. Impact of Segmentation Errors on the Bubble Tracking

9.6.3. Physical Interpretation of Bubble Dynamics

9.6.4. Comparison with the State of the Art

9.7. Limitations of the Study

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Part D’énergie Renouvelable Dans la Consommation Finale Brute D’energie en France en 2023. Available online: https://batizoom.ademe.fr/indicateurs/part-des-energies-renouvelables-dans-la-consommation-finale-brute-delectricite (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- IEA. Share of Renewables in Energy Consumption. Available online: https://www.iea.org/countries/france/renewables (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- CEA. CLEFS CEA—Number 50/51—HIVER 2004-2005 P25. Available online: https://www.cea.fr/multimedia/Documents/publications/clefs-cea/archives/fr/024a025alleau.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Production De L’Hydrogene. Available online: https://www.connaissancedesenergies.org/fiche-pedagogique/production-de-lhydrogene (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- CEA. CLEFS CEA—Number 50/51—HIVER 2004-2005 P31. Available online: https://www.cea.fr/multimedia/Documents/publications/clefs-cea/archives/fr/031a033baudouin.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- ADEME. La France Pourra-T-Elle Produire Son Propre Hydrogène Vert De Façon Compétitive? Available online: https://hydrogentoday.info/ademe-france-produire-hydrogene-vert/ (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Hessenkemper, H.; Starke, S.; Atassi, Y.; Ziegenhein, T.; Lucas, D. Bubble identification from images with machine learning methods. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2022, 155, 104169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W., Frangi, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colliard-Granero, A.; Gompou, K.A.; Rodenbücher, C.; Malek, K.; Eikerling, M.H.; Eslamibidgoli, M.J. Deep learning-enhanced characterization of bubble dynamics in proton exchange membrane water electrolyzers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 14529–14537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Chen, X.; Cen, L.; Xie, Y.; Yin, Z. Aluminum Electrolysis Fire-Eye Image Segmentation Based on the Improved U-Net Under Carbon Slag Interference. Electronics 2025, 14, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, J.H.; Ravichandran, M.; Su, G.; Phillips, B.; Bucci, M. Automated bubble analysis of high-speed subcooled flow boiling images using U-net transfer learning and global optical flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2023, 159, 104336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, M.J.; Field, C.R.; Grae, L.H.L.; Rickman, J.M.; Field, K.G.; Barmak, K. A comparative analysis of YOLOv8 and U-Net image segmentation approaches for transmission electron micrographs of polycrystalline thin films. APL Mach. Learn. 2025, 3, 036105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, X. Recent Progress in Electrocatalysts for Water Electrolysis. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudula-Jopek, A. Hydrogen Production: By Electrolysis; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schalenbach, M.; Tjarks, G.; Carmo, M.; Lueke, W.; Mueller, M.; Stolten, D. Acidic or alkaline? towards a new perspective on the efficiency of water electrolysis. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, F3197–F3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolten, D.; Emonts, B. Hydrogen Science and Engineering: Materials, Processes, Systems and Technology; Wiley-VCH: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S.D.R.; Hulme, A. Effect of bubbles attached to an electrode on electrical resistance and dissolved gas concentration. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1983, 387, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, H.; Nishida, T.; Konishi, Y.; Fukunaka, Y.; Ito, Y.; Kuribayashi, K. Water electrolysis under microgravity: Part 1. Experimental technique. Electrochim. Acta 2003, 48, 4119–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z.; Rox, H.; Ramos, Z.; Baumann, R.; Ravishankar, R.; Czurratis, P.; Yang, Z.; Lasagni, A.F.; Eckert, K.; Czarske, J.; et al. Scanning Acoustic Microscopy for Quantifying Two-phase Transfer in Operando Alkaline Water Electrolyzer. J. Power Sources 2025, 660, 238575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rox, H.; Bashkatov, A.; Yang, X.; Loos, S.; Mutschke, G.; Gerbeth, G.; Eckert, K. Bubble size distribution and electrode coverage at porous nickel electrodes in a novel 3-electrode flow-through cell. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.11550v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.P.P.R.; Souza, R.R.; Pereira, J.S.; Oliveira, J.D.; Moita, A.S. Synergistic effects of piezoelectric actuators and electrode architecture in alkaline water electrolysis. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 83, 104667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilastik. Ilastik. Available online: https://www.ilastik.org/documentation/pixelclassification/pixelclassification (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Hébert, P.; Laurendeau, D. Traitement Des Images (Part 1: Pretreatment). Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/498672954/Resume-Rtrait-Ement-Image (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- IBM. Qu’est Ce Qu’une Forêt D’Arbres Décisionnels. 59 Analysis of Bubble Dynamics on Electrodes via High-Speed Image Processing. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/frfr/think/topics/random-forest (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- PrBenlahmar. Les Réseaux De Neurones Convolutifs. Available online: https://datasciencetoday.net/index.php/en-us/deep-learning/173-les-reseaux-de-neuronesconvolutifs (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Taparia, A. U-Net Architecture Explained. Available online: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/machine-learning/u-net-architecture-explained/ (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- ImageJ Official Website. TrackMate LAP Trackers. Available online: https://imagej.net/plugins/trackmate/trackers/lap-trackers (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Chen, B.; Ekwonu, M.C.; Zhang, S. Deep learning-assisted segmentation of bubble image shadowgraph. J. Vis. 2022, 25, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, A.; Bashkatov, A.; Eftekhari, M.; Yang, X.; Strasser, P.; Mutschke, G.; Eckert, K. Oxygen versus Hydrogen Bubble Dynamics during Water Electrolysis at Microelectrodes. PRX Energy 2025, 4, 013011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaoka, K.; Wakuda, K.; Kanemoto, R.; Suwa, H.; Araki, T. Deep learning-based bubble detection with automatic training data generation: Application to the PEM water electrolysis. Trans. JSME 2023, 89, 22-00325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinapan, I.; Lin-Kwong-Chon, C.; Damour, C.; Kadjo, J.-J.A.; Benne, M. Oxygen Bubble Dynamics in PEM Water Electrolyzers with a Deep-Learning-Based Approach. Hydrogen 2023, 4, 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craye, E.J.B. Bubble Quantification in the Near Electrode Region in Alkaline Water Electrolysis. TU Delft Repository. 2023. Available online: https://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:f85ef347-0207-4481-999e-a0c87d7a0ca1 (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Lee, J.W.; Sohn, D.K.; Ko, H.S. Study on bubble visualization of gas-evolving electrolysis in forced convective electrolyte. Exp. Fluids 2019, 60, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Study of Bubble Dynamics and Mass Transport in Alkaline Water Electrolysis: Insights from Event-Based Imaging. UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Master’s Thesis, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6dh3w0ds (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Zerrougui, I.; Li, Z.; Hissel, D. Comprehensive Modeling and Analysis of Bubble Dynamics and its Impact on PEM Water Electrolysis Performance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Fundamentals and Development of Fuel Cells, Ulm, Germany, 25–27 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Metric | Ilastik (CPU) |

|---|---|

| Mean Inference Time per Frame | 8–15 ms/frame |

| Total Runtime for 100-frame Sequence | 0.8–1.5 s |

| Peak RAM Usage | 1.5–2.0 GB |

| Metric | U-Net Training (GPU) |

|---|---|

| Training Time per Epoch (24 images + augmentation) | 10–14 s/epoch |

| Total Training Time (100 epochs) | 17–25 min |

| GPU Memory Usage | 3–5 GB VRAM |

| Metric | U-Net Inference (GPU) | U-Net Inference (CPU) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Inference Time per Frame | 2.5–4.5 ms/frame | 45–70 ms/frame |

| Total Runtime for 100-frame Sequence | 0.25–0.45 s | 4.5–7.0 s |

| Peak RAM Usage | 2–3 GB | 2–3 GB |

| Metric | Frame 1 (0.160 A) | Frame 100 (0.190 A) | Model Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| IoU (Intersection over Union) | Ilastik: 0.69 | Ilastik: 0.69 | ≈Equal |

| U-Net: 0.68 | U-Net: 0.68 | ||

| RMSE (mm) | Ilastik: 0.041 | Ilastik: 0.024 | Ilastik better |

| U-Net: 0.062 | U-Net: 0.039 | ||

| Relative Error (%) | Ilastik: 20% (200 µm) | Ilastik: 16% (150 µm) | Ilastik better |

| U-Net: 31% (200 µm) | U-Net: 26% (150 µm) | ||

| Prediction Bias | Ilastik: Overestimation | Ilastik: Overestimation | _ |

| U-Net: Underestimation | U-Net: Underestimation | ||

| Distribution Alignment | Good shape match, | Chaotic, less aligned | Frame 1 Better |

| lower Peak |

| Current | Real Bubble Count | Predicted Bubble Count (U-Net + TrackMate) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.160 A (Silent) | 90 | 159 |

| 0.190 A (Silent) | 92 | 205 |

| 0.190 (Piezo) | 59 | 71 |

| 0.250 A (Silent) | 104 | 165 |

| Aspect | Literature References | This Work |

|---|---|---|

| Image segmentation | Mostly threshold-based [28,29] | Ilastik vs. U-Net |

| Training dataset | Large or synthetic [9,30,31] | Small experimental dataset |

| Bubble tracking | Often assumed reliable [9,29,30] | Explicit error analysis |

| Electrolysis imaging | Static images [32,33,34,35] | High-speed imaging |

| Limitations discussed | Rarely explicit [30,31,32,33] | Explicit limitations section |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pereira, J.; Souza, R.; Normand, A.; Moita, A. Image-Based Segmentation of Hydrogen Bubbles in Alkaline Electrolysis: A Comparison Between Ilastik and U-Net. Algorithms 2026, 19, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010077

Pereira J, Souza R, Normand A, Moita A. Image-Based Segmentation of Hydrogen Bubbles in Alkaline Electrolysis: A Comparison Between Ilastik and U-Net. Algorithms. 2026; 19(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010077

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira, José, Reinaldo Souza, Arthur Normand, and Ana Moita. 2026. "Image-Based Segmentation of Hydrogen Bubbles in Alkaline Electrolysis: A Comparison Between Ilastik and U-Net" Algorithms 19, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010077

APA StylePereira, J., Souza, R., Normand, A., & Moita, A. (2026). Image-Based Segmentation of Hydrogen Bubbles in Alkaline Electrolysis: A Comparison Between Ilastik and U-Net. Algorithms, 19(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010077