Abstract

To obtain actionable information for humanitarian and other emergency responses, an accurate classification of news or events is critical. Daily news and social media are hard to classify based on conveyed information, especially when multiple categories of information are embedded. This research used large language models (LLMs) and traditional transformer-based models, such as BERT, to classify news and social media events using the example of the Sudan Conflict. A systematic evaluation framework was introduced to test GPT models using Zero-Shot prompting, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), and RAG with In-Context Learning (ICL) against standard and hyperparameter-tuned bert-based and bert-large models. BERT outperformed GPT in F1-score and accuracy for multi-label classification (MLC) while GPT outperformed BERT in accuracy for Single-Label classification from Multi-Label Ground Truth (SL-MLG). The results illustrate that a larger model size improves classification accuracy for both BERT and GPT, while BERT benefits from hyperparameter tuning and GPT benefits from its enhanced contextual comprehension capabilities. By addressing challenges such as overlapping semantic categories, task-specific adaptation, and a limited dataset, this study provides a deeper understanding of LLMs’ applicability in constrained, real-world scenarios, particularly in highlighting the potential for integrating NLP with other applications such as GIS in future conflict analyses.

Keywords:

large language models; transformers; generative AI; BERT; GPT; NLP; RAG; war conflict; humanitarian crisis 1. Introduction

The massive influx of media news, particularly for dynamic and fast-evolving situations such as armed conflicts, presents a significant obstacle for conflict analysts who must quickly comprehend, classify, and extract actionable information for intelligence. Manual classification is not only time-consuming but could also be impractical, given the limited timeframe and available resources during crisis situations.

Effectively classifying news content is vital for multiple applications, including conflict monitoring, humanitarian aid, and timely decision-making by policymakers. Accurate classification supports high-quality information retrieval, while efficient methods can enhance processing speed, both of which are essential for timely and informed responses to emergency events. However, news classification is inherently challenging, given the complexities of language, the presence of overlapping semantic categories, and the frequent occurrence of ambiguous or incomplete information in media data [1].

The rapid growth in digital media has intensified the challenges associated with effectively classifying news content. Traditional news classification methods, including machine learning and early deep learning architectures, have evolved significantly. Transformer-based models such as BERT and GPT offer advanced capabilities by capturing nuanced contextual information more effectively [2,3,4].

In natural language processing (NLP), classification plays a critical role in organizing, analyzing, and deriving insights from unstructured text data, a task that has become increasingly challenging due to the rapid expansion of digital media and the sheer volume of news articles published daily [5,6,7,8,9]. Given the technological evolution and the complexities in conflict-related news classification, this study evaluated and compared the effectiveness of state-of-the-art NLP approaches, specifically BERT and GPT, in classifying conflict-related articles related to the Sudan Conflict. This research included testing different methodologies, such as Zero-Shot prompting, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), and RAG with In-Context Learning (ICL) for GPT models, alongside both base and large versions of BERT, each evaluated in standard and hyperparameter-tuned configurations, to identify the optimal approach for Single-Label classification from Multi-Label Ground Truth (SL-MLG) and Multi-Label Classification (MLC). By systematically assessing these methods, this study provides insights into their applicability, reliability, and limitations, ultimately informing the best practices for applying NLP-based classification methods to media news classification in rapidly evolving conflicts and other scenarios.

Humanitarian responders and crisis managers rely on rapid, accurate classification of news incidents to allocate aid, coordinate evacuations, and minimize casualties. Mislabeling or delays can misdirect resources and jeopardize lives. While prior research has demonstrated how transformer-based models like BERT or GPT perform well in standard news classification tasks [10,11,12,13], existing studies often assume clean, balanced datasets and focus on structured or routine topics. For example, Sufi [10] discussed mathematical models for AI-based news analytics, and Chen et al. [11] applied BERT-CNN hybrids for long-text news classification. However, crisis news reporting poses distinct challenges, including fast-changing events, ambiguous wording, overlapping categories, and sensitive content. Conflict-related datasets are often small, highly imbalanced, and require expert annotation, which is time-consuming and resource-intensive. To address this gap, we systematically compared BERT and GPT in crisis news classification within these real-world constraints, using the Sudan Conflict as an example and analyzed how different prompting and retrieval strategies affect their classification performance.

2. Related Work

2.1. Text Classification in NLP

Text classification is a fundamental task in NLP that involves assigning textual data to predefined labels or categories based on its content. It serves as a critical component in various applications, including sentiment analysis, spam detection, topic classification, and document classification. These applications rely on accurate classification to support efficient information retrieval and enable automated decision-making [14,15,16,17]. Researchers have developed a range of approaches for text classification, evolving from rule-based methods and statistical models to machine learning (ML) and deep learning techniques [6,18].

Early text classification models relied on traditional ML algorithms, such as Naïve Bayes, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Random Forest, which leveraged handcrafted features like term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) and n-grams to represent text [19,20]. While these approaches demonstrated reasonable performance in structured datasets, they struggled with capturing the complex semantic and syntactic structures of natural language. To address these limitations, deep learning (DL) models emerged as a more effective solution, significantly improving text classification accuracy by automatically learning hierarchical features from raw text.

Among the early DL approaches, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) were widely adopted for text classification due to their ability to capture local patterns and word dependencies through convolutional filters [21,22]. CNN-based models performed well in tasks requiring sentiment analysis and short-text classification but were limited in handling long-range dependencies due to their fixed-size receptive fields. Meanwhile, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, became popular for their ability to model sequential dependencies and effectively handle text inputs of varying lengths, such as short phrases or long documents [23]. LSTM demonstrated superior performance in capturing word order and contextual relationships, making it effective for tasks like document classification and named entity recognition [24]. However, both CNNs and LSTMs suffered from inefficiencies when dealing with long-range dependencies and were computationally expensive due to their sequential nature.

A significant breakthrough in NLP came with the introduction of the Transformer architecture by Vaswani et al. [25], which revolutionized text classification by addressing the shortcomings of RNN-based models. Transformer’s self-attention mechanism enabled it to capture long-range dependencies more effectively by processing all tokens in parallel, rather than sequentially. This architectural innovation significantly improved performance across various NLP tasks, including machine translation, text classification, and question answering [26,27].

Building upon the Transformer framework, BERT [2] and GPT [3] emerged as state-of-the-art models for text classification and other NLP applications. BERT introduced a bidirectional training approach, enabling a deeper contextual understanding of text, while GPT leveraged autoregressive pretraining to generate coherent and contextually relevant outputs. These models set new benchmarks for text classification by surpassing previous DL methods in accuracy and adaptability across various domains [28]. The evolution of text classification methods—from traditional statistical models to DL and Transformer-based architectures—has reshaped how textual data is analyzed and classified. While earlier approaches like CNNs and LSTMs laid the foundation for deep learning in NLP, Transformer-based models have achieved unprecedented performance by capturing complex contextual dependencies with greater efficiency. However, despite the success of Transformer-based models like BERT and GPT, several challenges remain, particularly in classifying texts with overlapping semantic categories, interpreting specialized terminology, and adapting to domains with limited annotated data.

This study addresses these limitations by evaluating how BERT and GPT models perform in conflict-related news scenarios, emphasizing nuanced label selection and context-sensitive adaptation, as illustrated by the Sudan Conflict case study.

2.2. Text Classification by BERT

BERT has significantly advanced text classification by introducing a novel bidirectional training approach that captures linguistic context more effectively than its predecessors. Unlike earlier models that relied on unidirectional context processing, BERT simultaneously considers both preceding and succeeding tokens within a sequence, allowing for a richer understanding of the semantics and syntax [2]. This bidirectional framework enables BERT to disambiguate meaning, recognize contextual nuances, and enhance classification accuracy, making it highly effective for complex NLP tasks [29,30].

The ability to capture subtle semantic and syntactic relationships has positioned BERT as a powerful tool for a wide range of domain-specific text classification applications. In legal document analysis, BERT has been employed to classify case laws, contracts, and regulatory texts with high precision, reducing the need for manual annotation [31]. Similarly, in sentiment analysis, BERT effectively distinguishes nuanced opinions in product reviews, social media posts, and customer feedback, outperforming traditional deep learning models [32]. In news classification, BERT has been widely used to classify articles based on themes such as politics, finance, and global conflicts, demonstrating its adaptability across diverse textual datasets [33]. For instance, Chen [34] highlighted how BERT modeling achieves robust accuracy for classifying concise and ambiguous news headlines, showcasing its effectiveness even for short-form news contexts. Bedretdin [35] demonstrated that augmenting BERT with topic models and structural features can further improve classification performance in multi-class media research, a strategy relevant for complex crisis news datasets.

Comparative studies have shown that BERT consistently achieves higher accuracy scores than traditional machine learning and deep learning models. For instance, research indicates that BERT outperforms Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs), LSTM networks, CNNs, and even other Transformer-based models like RoBERTa in multi-class text classification tasks [36,37]. Its pre-training on large-scale corpora, followed by domain-specific fine-tuning, allows BERT to generalize well while also being adaptable to specialized tasks. However, BERT’s performance can be limited when training data is scarce or when dealing with overlapping semantic categories. This research explored these limitations through comparative evaluations with GPT-based approaches.

2.3. Text Classification by GPT

GPT represents another significant advancement in NLP, extending the capabilities of the Transformer architecture by adopting an autoregressive learning approach. Unlike BERT, which relies on bidirectional training to understand both preceding and succeeding tokens in a sequence, GPT processes text in a unidirectional manner, predicting the next word based solely on previous tokens [3]. This autoregressive approach makes GPT particularly well-suited for text generation tasks, enabling it to excel in text completion, summarization, dialogue systems, and creative writing applications [38,39].

One of GPT’s major strengths in text classification lies in its ability to perform tasks with minimal task-specific training. Unlike BERT, which typically requires fine-tuning on large number of labeled datasets for domain-specific classification, GPT leverages few-shot and zero-shot learning to classify text based on structured prompts [40,41]. This characteristic enables GPT to generalize across multiple domains without extensive retraining, making it particularly useful in low-resource environments where annotated training data is limited. Additionally, GPT’s prompt engineering capabilities allow users to dynamically guide the model’s classification behavior, reducing the dependency on traditional fine-tuning methods [12].

However, while GPT offers greater flexibility and adaptability, its autoregressive nature introduces inherent limitations compared to BERT. Since GPT processes text sequentially, it lacks BERT’s full bidirectional context, which can be crucial for understanding nuanced relationships between words in complex classification tasks. As a result, BERT often outperforms GPT in domain-specific classification, particularly in scenarios where fine-grained contextual understanding is essential [42]. Moreover, GPT’s output variability, which makes it effective in generative tasks, can introduce inconsistencies in classification performance, requiring additional prompt tuning to maintain accuracy and reliability across different datasets [28].

2.4. Current Problems and Contributions

In summary, despite significant advancements in text classification through models like BERT and GPT, several problems persist, particularly in handling MLC, low-resource datasets, and classification consistency. Traditional supervised classification approaches require a large amount of annotated training datasets, which are often unavailable for specific domains. While BERT improves classification accuracy through bidirectional context modeling, it demands extensive fine-tuning and computational resources. On the other hand, GPT’s zero-shot and few-shot learning capabilities offer adaptability but may generate inconsistent outputs, making it less reliable for structured classification tasks.

These problems become more pronounced in complex conflict-related articles. For example, MLC is required to classify articles into multiple categories (e.g., war crimes, humanitarian crises, and military operations), yet existing models struggle with overlapping categories and imbalanced datasets. The effectiveness of classification is further influenced by data constraints, ambiguous text, and entity overlaps, which complicate model training and evaluation. This research explored and optimized LLM-based classification techniques, focusing on prompt-based strategies with GPT and both standard and hyperparameter-tuned versions of BERT. By systematically comparing GPT’s prompt-based methods against BERT’s hyperparameter-tuned classification, the study evaluated approaches for improving classification performance.

3. Data Sources

A total of 423 articles (such as in Table 1) related to the Sudan Conflict, covering January 2024 to November 2024, were selected and analyzed by multiple Sudan Conflict experts as the ground truth. The annotated dataset covered 17 categories including military operations, damage or destruction of civilian critical infrastructure, willful killing of civilians, etc. (detailed in Table 2).

Table 1.

The structure of the incident dataset and an example of an incident.

Table 2.

Category definitions for conflict-related incidents.

Each article was labeled as one or more categories based on its content. To ensure consistency and accuracy, the labels were cross-verified by multiple experts. Given the overlapping nature of certain categories, challenges arose in distinguishing between similar classifications. To address this, detailed category definitions were developed by the Sudan Conflict experts who were also responsible for the labeling. These guidelines provided annotators with clear decision-making criteria, minimizing ambiguity and ensuring uniform interpretation of classification rules across all annotated articles.

Table 1 presents the data structure and an example of an incident. The cell “Incident Narrative” was put into the various open-source LLMs, and the ‘Ground Truth’ field was used to verify and validate the outputs of the LLMs.

Table 2 outlines each category and its corresponding definition, which was also used in the prompts for the RAG-ICL approach, where definitions guide classification via retrieved in-context examples.

The dataset was partitioned into training (90%) and testing (10%) subsets, with an additional 85/15 validation split within the training portion. Table 3 summarizes the distribution of articles across incident categories for the training, validation, and test sets, highlighting the dataset’s constrained size and pronounced class imbalance.

Table 3.

Number of articles per incident category and dataset split. “Total Occurrences” are the sum of the category assignments; “Total Rows” are the number of unique articles per split.

4. Methodologies

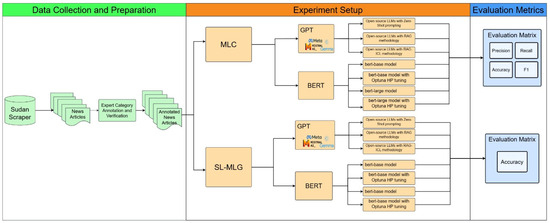

This study evaluated the text classification performance of two classification frameworks (Figure 1): SL-MLG and MLC. The experiment setup involved testing GPT and BERT models under multiple configurations to assess their ability to classify news articles related to the Sudan Conflict.

Figure 1.

Workflow diagram for comparative evaluation of BERT and GPT in SL-MLG and MLC.

For SL-MLG, both models are prompted to choose a single label that best fits the article. If the selected label appears among the expert-assigned labels, it is considered correct. This approach simplifies evaluation while still using multiple labels as the ground truth. In contrast, the MLC framework allows models to assign one or more relevant categories to each article, capturing the complexity of real-world reporting where news often spans multiple categories. The GPT and BERT models were tested across both frameworks to compare their classification performance on Sudan Conflict articles.

The BERT models were evaluated in two settings: one using default hyperparameters and another with hyperparameter tuning to optimize classification accuracy. The GPT models, on the other hand, were tested under three strategies: Zero-Shot learning, RAG without category definitions, and RAG with ICL, with expert-defined category descriptions provided. These configurations allowed for a comparative analysis of model adaptability and classification efficiency under different learning conditions.

For SL-MLG, classification performance was measured using accuracy alone, while for MLC, it was evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. By systematically analyzing these models across different setups, this study aimed to identify the best approach for classifying news into single and multiple categories.

4.1. Methods

4.1.1. BERT

To maintain a focused comparison between BERT and GPT, encoder types such as XLM-RoBERTa and DeBERTa were not included, as this study was centered on comparing the traditional BERT variants and GPT models. The chosen BERT classification framework was implemented for both MLC and Single-Label Classification from SL-MLG using two configurations: a standard BERT model with default hyperparameters and a hyperparameter-tuned model optimized via Optuna [43]. Both configurations used the bert-base-uncased and bert-large-uncased variants from the Hugging Face Transformers library, fine-tuned to predict from a fixed set of K conflict-related categories. Text inputs were processed using the BertTokenizer for consistent tokenization, truncation, and padding.

Furthermore, no explicit class weights or custom loss functions were applied. However, using Optuna, key hyperparameters were optimized—including learning rate, batch size, number of epochs, dropout rate, and weight decay—to improve the classification performance under a data imbalance.

Each news article was denoted as an input sequence , where indexes the article in a dataset of size . Each article was paired with a binary ground-truth label vector , where indicates that article belongs to category k, and 0 otherwise.

For the SL-MLG task, the model computes an output logit vector , where denotes the model parameters, and each component represents the raw, unnormalized score for category k. The logits are converted into class probabilities via the softmax function:

where is the predicted probability distribution over all categories. is the predicted probability that article belongs to category k. The sum across all k ensures that

The predicted label is selected as the index k with the highest predicted probability:

This prediction is deemed correct if it appears in the original ground truth multi-label set:

In the MLC setting, the model again produces logits . Instead of using softmax, a sigmoid activation is applied independently to each category score:

where is the predicted probability that article belongs to category k. Each score is interpreted independently, allowing multiple labels per article. The final predicted label set is computed by applying a threshold to each probability:

This allows the model to assign multiple categories to a single article.

To address the concern regarding the limited size of the test set in the initial 90/10 training–testing split, which resulted in only the same 43 articles used in the evaluation, we implemented a 5-fold cross-validation 80/20 training–testing split strategy to strengthen the validity and reliability of our results. By adopting k-fold cross-validation, we ensured that each article in the dataset was used for both training and evaluation across different folds, providing a more comprehensive and balanced assessment of the model’s performance. This approach further mitigated any potential bias introduced by relying on a single, fixed test subset and helped verify that the results were not dependent on a particular partition of the data.

The cross-validation procedure was applied exclusively to the BERT models. This is because BERT requires supervised fine-tuning on labeled data, and its architecture supports retraining across multiple folds without excessive overhead. In contrast, the GPT-based models in this study were used in a prompt-based setting without additional fine-tuning. Accordingly, cross-validation was limited to BERT.

4.1.2. GPT

The GPT-based classification framework was designed to evaluate the performance of seven open-source LLMs: Gemma2-9b, Gemma2-27b, Llama3.3-70b, Llama3.2-3b, Llama3.1-70b, Llama3.1-7b, and Mistral-7b. The goal was to identify the most effective model for both SL-MLG and MLC in classifying conflict-related news articles.

To analyze their performance under varying learning conditions, three distinct prompting methodologies were employed:

(1) Zero-Shot Prompting—The model was only provided with the input article , with no additional contextual information. This setting evaluates the model’s raw generalization ability based on its pre-trained knowledge:

(2) RAG Without Definitions—The model received a prompt composed of the article and a flat list of category names . This format provides some task grounding while still relying on the model’s internal representations:

(3) RAG with In-Context Learning (ICL): The prompt was expanded to include the article , category names , and detailed expert-annotated definitions for each category . This setup offers the highest level of task-specific guidance:

To support the RAG and RAG ICL approaches, Facebook AI Similarity Search (FAISS) was employed to build an efficient dense vector index of the expert-defined category definitions and curated context examples [44]. During inference, the top-k most relevant vectors were retrieved and appended to each prompt, enabling the LLM to incorporate precise in-domain context without relying on external documents or a general web-scale corpus.

All GPT model experiments were conducted on a high-performance workstation equipped with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) w3-2423 CPU, 128 GB of RAM, and dual NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPUs (each with 48 GB of VRAM). This setup enabled efficient execution of large-scale models such as Gemma2–27B and Llama3.1–70B, particularly for RAG pipelines involving long-context prompts.

4.2. Evaluation Matrix

4.2.1. BERT

The BERT-based and BERT-large classification models were evaluated using different metrics tailored to the requirements of SL-MLG and MLC tasks. These evaluation metrics ensured a comprehensive assessment of model performance and provided insights into the impact of hyperparameter tuning on classification accuracy.

For SL-MLG, accuracy served as the primary evaluation metric, reflecting the model’s ability to select the single label that best describes the primary issue from multiple ground-truth categories. Predictions were generated using a softmax activation function, which converted the model logits into probability distributions across all categories. The category with the highest probability was selected as the final classification.

To assess alignment with expert labeling, accuracy was calculated by verifying whether the predicted category matched any of the ground-truth labels assigned by the experts. This metric emphasized the model’s ability to prioritize the most relevant category while adhering to the strict single-label requirement of the SL-MLG framework.

For MLC, model performance was measured using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, calculated on a per-category basis and averaged using a weighted scheme. These metrics were chosen to assess both precision (the proportion of correctly predicted labels among all predicted labels) and recall (the proportion of correctly predicted labels among all actual labels assigned to an article), with F1-score providing their harmonic mean, ensuring a balanced evaluation of prediction correctness and completeness.

Predictions were generated by applying a sigmoid activation function to the model logits, converting them into probability scores for each category. A threshold of 0.5 was used to determine whether a category was assigned to an article. The evaluation pipeline compared these binary predictions against the ground truth labels from the test dataset, computing accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score accordingly. The results were analyzed for both the standard BERT model with fixed hyperparameters and the hyperparameter-tuned BERT model optimized using Optuna, highlighting the effects of parameter tuning on classification performance.

4.2.2. GPT

The GPT-based classification models were evaluated using distinct metrics tailored to the SL-MLG and MLC frameworks. This evaluation aimed to assess GPT’s ability to align with expert-labeled categories while identifying potential strengths and limitations of its classification performance.

For SL-MLG, model performance was evaluated using an exact-match accuracy metric, which assessed whether the model’s single predicted category matched any of the ground-truth labels. To ensure consistency in comparison, both the ground-truth labels and model outputs were normalized by converting text to lowercase and removing extra spaces. Each prediction was assigned a binary score: 1 if the predicted category matched any of the annotated labels, and 0 otherwise. These scores were then averaged across all test samples to produce the final accuracy score. This single-metric evaluation reflects GPT’s effectiveness in selecting the single label that best describes the primary issue from multiple valid options and avoids the use of precision or recall, which are less applicable when evaluating a single predicted label against multiple ground-truth categories, as in SL-MLG.

For MLC, model performance was measured using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, calculated at both the article and category levels. Additionally, false positives (FPs), false negatives (FNs), and true positives (TPs) were tracked to analyze classification biases and potential weaknesses in specific categories. To compute these metrics, predicted categories were extracted from the model’s textual outputs and compared against the ground-truth labels. The evaluation process treated these extracted categories as unordered sets, ensuring that variations in category ordering did not affect results.

- Accuracy was determined by checking whether the predicted set of categories exactly matched the ground-truth set for each article.

- Precision measured the proportion of correctly predicted categories among all predicted labels.

- Recall quantified the proportion of relevant categories successfully identified by the model.

- F1-score, the harmonic mean of precision and recall, provided a balanced assessment of classification performance.

Additionally, the per-category analysis aggregated FP and FN counts across the dataset, identifying categories where the model struggled.

5. Results

5.1. SL-MLG

The overall performances of the three GPT methodologies (Zero-Shot, RAG, and RAG ICL) and two BERT configurations (standard and hyperparameter-tuned) in SL-MLG classification were compared (Table 4). The evaluation focused on accuracy and total runtime to assess the models’ ability to prioritize a single most relevant category from multi-label ground truth.

Table 4.

SL-MLG results of BERT and GPT models. Total runtime is split into three columns: TUNING, TRAINING, and INFERENCE. Only BERT models include values for TUNING and TRAINING due to the need for hyperparameter tuning and supervised training. GPT models rely solely on prompt-based inference, resulting in blank entries for TUNING and TRAINING columns.

The GPT models exhibited high accuracy overall. Under the RAG ICL setting, the Llama3.3-70b and Llama3.1-70b models achieved the highest performance, both reaching 90.70% accuracy. In comparison, Gemma2-27b and Llama3.1-7b followed closely with 86.05% accuracy under RAG ICL. The RAG methodology without category definitions also yielded competitive results, with Llama3.3-70b achieving 86.05% accuracy, demonstrating that retrieval-based approaches can enhance classification performance.

Zero-Shot configurations offered the best computational efficiency, with runtimes as low as 9 s per inference, but at the cost of lower accuracy, peaking at 76.74% for Llama3.3-70b. This suggests that while Zero-Shot prompting enables rapid inference, its lack of contextual grounding affects classification precision.

BERT models performed competitively, though with lower accuracy than GPT models. The hyperparameter-tuned bert-large model achieved the highest accuracy of all the BERT configurations at 83.72%, slightly outperforming the standard bert-large version (74.42%). However, the tuned model required significantly longer runtimes (1243 m 48 s vs. 28 m 31 s), indicating that while hyperparameter optimization yielded accuracy gains in this specific SL-MLG setting, this also came with a significant time increase.

5.2. MLC

The overall performances (Table 5) of the three GPT methodologies (Zero-Shot, RAG, and RAG ICL) and two BERT configurations (standard and hyperparameter-tuned) in the MLC task were compared, focusing on accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and runtime.

Table 5.

MLC results of GPT and BERT models. Total runtime is split into three columns: TUNING, TRAINING, and INFERENCE. Only BERT models have tuning and training times; GPT models rely on prompt-based inference, explaining the blank entries in the TUNING and TRAINING columns.

The GPT models exhibited varying performance across different methodologies. BERT models, on the other hand, demonstrated similarly consistent performances, with hyperparameter tuning providing slight improvements in scores. The bert-large hyperparameter-tuned model achieved the highest F1-score (68.90%), outperforming the close second, the Llama3.1-70b model under RAG counterpart (68.80%). Llama3.1-70b under RAG outperformed its counterpart Llama3.1-70b under RAG ICL (67.00%). Similarly, Llama3.3-70b performed better in F1-score under RAG (67.30%) than under RAG ICL (64.42%), indicating that RAG generally outperformed RAG ICL, particularly for larger models. However, RAG ICL remained competitive, with Gemma2-27b showing comparable F1-scores. Accuracy among the GPT models remained modest, with the highest accuracy for the GPT models being recorded at 25.58% for Llama3.1-70b under RAG ICL. Recall scores, however, were consistently strong across all methodologies, highlighting GPT’s ability to comprehensively capture relevant categories, even at the expense of precision.

The BERT models demonstrated higher precision than the GPT models, with the bert-large hyperparameter-tuned configuration achieving an F1-score of 68.90% and a precision of 75.70%, outperforming the standard bert-large model (F1-score of 54.62%, precision of 64.32%). However, the BERT models exhibited lower recall scores than the GPT models, with both the hyperparameter-tuned bert-base model and standard bert-base model achieving recall scores of 57.78%, indicating that while BERT excels in precise category assignment, it struggles to comprehensively capture all relevant categories.

The highest overall F1-score (68.90%) was achieved by the hyperparameter-tuned bert-large model, surpassing the best GPT model, Llama3.1-70b under RAG, with an F1-score of 68.80%. Similarly, in terms of accuracy, all the BERT models achieved higher scores than all the GPT models with the hyperparameter-tuned bert-large model achieving the highest score of 41.86%.

Computational efficiency differed significantly between the BERT and GPT models. Since BERT requires both training and inference time, the standard bert-base model completed training and inference in 9 min and 43 s, and the standard bert-large model completed training and inference in 14 m 55 s. For the hyperparameter-tuned models, the runtime was divided into three parts; (1) tuning, (2) training, and (3) inference. The bert-base hyperparameter-tuned version required a total of 187 min and 45 s while the bert-large hyperparameter-tuned version took a total of 1351 m 14 s (~22.5 h) due to the ~3X larger parameter size bert-large has over bert-base. In contrast, the GPT models only required inference time, with the best model GPT model, Llama3.1-70b under RAG, running in 2 m 30 s, completing the runtime in a significantly faster margin compared to the hyperparameter-tuned bert-large model, which only beat it by 0.10%.

This highlights a key trade-off between computational cost and classification performance, where BERT incurs higher computational overhead due to tuning, training, and inference, while GPT achieves rapid inference but relies heavily on prompt engineering for classification accuracy.

Table 6 presents an example from Llama3.3-70b under RAG ICL, in which the model achieved a perfect multi-label classification. This example illustrates the model’s ability to correctly identify all relevant categories in a conflict narrative, aligning with its high F1-score and strong recall score in the overall MLC results. Furthermore, it demonstrates how larger-parameter models like Llama3.3-70b outperform smaller models such as Llama3.1-7b, which achieved an F1-score of only 50% on the same example because it missed two of the three ground-truth categories: Willful killing of civilians and Indiscriminate use of weapons.

Table 6.

Example of an MLC result generated by Llama3.3-70B using the RAG ICL method.

5.3. K-Fold CV

To address concerns with the limited test size from the original 80/20 split (43 articles), 5-fold cross-validation was applied to strengthen the reliability of the evaluation. This was performed across four BERT configurations: MLC and SL-MLG using both bert-base-uncased and bert-large-uncased.

As shown in Table 7, performance improved across all metrics when using bert-large-uncased, particularly for MLC, which achieved an F1-score of 70.35 ± 2.12% and an accuracy of 39.24 ± 4.01%. In comparison, the original 90/10 split yielded lower MLC F1-scores of 62.85% (standard bert-base) and 54.62% (standard bert-large). Similarly, SL-MLG accuracy improved under cross-validation, with bert-large achieving 85.83 ± 3.53%, compared to 76.74% in the original split. These results underscore the importance of using cross-validation, especially in low-resource settings, to produce more robust and generalizable performance estimates.

Table 7.

K-Fold CV results for BERT models on MLC and SL-MLG without HP tuning.

Due to computational constraints, hyperparameter tuning via Optuna was excluded from the cross-validation runs. As a result, only standard BERT configurations without tuning were evaluated. Despite repeating training and inference across multiple folds, the average fold times remained reasonable, ranging from 9 m 16 s (bert-base) to 31 m 17 s (bert-large), further supporting the practicality of K-fold cross-validation for evaluating classification models in this domain.

6. Discussion

The experimental results demonstrate that both BERT and GPT exhibit distinct strengths and weaknesses in SL-MLG and MLC tasks, with differences in precision, recall, accuracy, computational efficiency, and adaptability. The choice between the two depends on the specific classification requirements, the need for model fine-tuning, and the constraints of the computational resources. Table 8 and Table 9 summarize the highest-performing algorithm from each table presented in the preceding sections.

Table 8.

Collective SL-MLG experimental results.

Table 9.

Collective MLC experimental results.

Furthermore, to support a fair and statistically robust evaluation, the BERT models were tested using both a traditional 90/10 training–testing split and 5-fold cross-validation. The initial 90/10 experiments provided a fast baseline and enabled hyperparameter tuning via Optuna, resulting in improved F1-scores but at the cost of a longer runtime. However, due to concerns about the same small test set size (43 articles), we introduced 5-fold cross-validation for both the MLC and SL-MLG tasks using bert-base and bert-large. This approach yielded higher and more stable performance metrics, particularly for bert-large, and confirmed that BERT performance scales reliably with model size. To ensure computational feasibility, hyperparameter tuning was excluded from the cross-validation runs, although the average fold runtimes remained manageable (9–31 min). This comprehensive evaluation strategy ensured that our conclusions about BERT model performance mitigated concerns regarding statistical significance and generalizability.

For both the SL-MLG and MLC tasks, larger models (e.g., Llama3.1-70b, Gemma2-27b, and bert-large) consistently outperformed their smaller counterparts (e.g., Llama3.1-7b, Gemma2-9b, and bert-base). This suggests that higher-parameter models benefit from increased contextual retention, enabling better generalization in complex classification tasks. For example, for MLC, Llama3.1-70b under RAG achieved an F1-score of 68.80%, outperforming Llama3.1-7b (57.22%). Similarly, Gemma2-27b under RAG ICL showed a superior F1-score (62.21%) compared to Gemma2-9b (53.03%). This trend suggests that higher-parameter models are better suited for handling nuanced, multi-label classification tasks, likely due to their enhanced capacity to model overlapping semantic categories.

A similar trend was observed in SL-MLG, where Llama3.1-70b achieved the highest accuracy (90.70%), surpassing Llama3.1-7b (86.05%). Likewise, Gemma2-27b (86.05% accuracy) outperformed Gemma2-9b (79.07%).

These results suggest that higher-parameter models improve classification accuracy, reinforcing their advantages in structured classification tasks. While model size contributes to the advantage in classification tasks, performance is also influenced by architectural differences between BERT and GPT, the choice of prompting strategy, and the inclusion of hyperparameter tuning.

Notably, a key trend observed in this study was the low performance of Llama3.2–3b across all metrics, which demonstrated low performance in SL-MLG and MLC. This underperformance was not due to the relatively small parameter size of 3B but primarily resulted from its guardrails. For example, in the Zero-Shot and standard RAG configurations, the model frequently refused to classify violent or sensitive content and instead returned refusal messages. However, when explicit category definitions were provided through the RAG ICL approach, this behavior was largely mitigated, and the model executed the classification task as intended. This finding underscores the critical role of carefully choosing the best prompting strategy for each domain-related task in order to ensure compliant behavior when utilizing LLMs for a task such as sensitive crisis-related text classification.

One of BERT’s primary advantages lies in its higher precision in multi-label classification tasks, where it consistently outperforms GPT in assigning categories with fewer false positives. Its bidirectional training mechanism allows it to capture deeper contextual relationships, leading to more accurate classifications in structured tasks. In the SL-MLG tasks, BERT also demonstrated better alignment with the ground-truth labels, achieving the highest accuracy among all configurations. This suggests that BERT’s fine-tuned models are better suited for tasks requiring exact category assignment. Additionally, BERT’s fine-tuning process enables structured optimization for domain-specific classification, allowing for more refined learning in well-defined datasets. Furthermore, BERT models produce more stable and deterministic outputs, whereas GPT’s responses may vary across different runs, making BERT more reliable for structured applications that require consistent and reproducible classifications.

However, BERT had notable limitations compared to GPT. One major drawback is its lower recall in MLC tasks, meaning it often fails to capture the complete set of relevant categories for an article. This conservative classification approach can lead to under-classification, where important categories are overlooked. Additionally, BERT’s reliance on supervised fine-tuning makes it computationally expensive, requiring extensive training for each new dataset. In contrast, GPT operates without the need for fine-tuning, significantly reducing the setup time. Furthermore, BERT’s limited adaptability to new domains makes it less flexible in handling unseen datasets. Since BERT relies on task-specific fine-tuning, it struggles to generalize as effectively as GPT’s in-context learning, which enables classification across a wide range of topics without retraining.

The RAG approach without definitions provided GPT models with only category names as prompts, requiring the model to rely solely on pre-trained knowledge for classification. This approach generally outperformed Zero-Shot prompting and, in some cases, even RAG ICL, particularly for larger models. For example, Llama3.1-70b under RAG achieved an F1-score of 68.80% in MLC, demonstrating that models with extensive pre-training can classify effectively without explicit category descriptions. In the SL-MLG tasks, RAG also showed competitive results, with Llama3.3-70b achieving an accuracy of 86.05%, only slightly below RAG ICL’s best-performing models.

The RAG ICL approach, which incorporated expert-annotated category definitions in the prompt, provided the highest classification accuracy across the SL-MLG tasks. This method improved classification precision by providing GPT with structured, contextual definitions of each category, guiding more accurate label selection during inference. For MLC, however, the results were more mixed. While RAG ICL improved classification accuracy, it did not consistently outperform RAG without definitions across all models. This suggests that while category definitions improve classification in SL-MLG tasks, they may introduce unnecessary constraints in MLC, where capturing multiple relevant labels is essential. Nevertheless, RAG ICL remains a viable approach for classification tasks requiring strict category definitions and interpretability.

Comparison with Similar Studies

To contextualize our contributions within the broader landscape of transformer-based text classification, a comparative analysis was conducted to compare this research to recent studies that have applied BERT, GPT, or similar models to news classification tasks. Particular emphasis was placed on works addressing long-form, multi-label, or crisis-related content. Table 10 summarizes each selected study’s methodological approach, domain focus, and key findings, and provides a comparison with this study.

Table 10.

Comparative summary of related studies and this research.

This comparison illustrates several key gaps addressed by this study. First, while previous works such as Sufi [10] and Fatemi et al. [12] leveraged powerful LLMs for structured news analytics, they operated on large, general-purpose datasets and did not address classification under multi-label or conflict-specific ambiguity. Others, like Brandt et al. [45], emphasized speed and domain tuning but did not explore prompting strategies or retrieval-augmented methods. Notably, most prior studies tested either BERT or GPT models individually, with limited emphasis on direct comparisons across prompting modes or under extreme class imbalance.

In contrast, our study systematically benchmarked multiple open-source GPT models and BERT models and configurations on a constrained, real-world conflict dataset annotated by domain experts. By incorporating retrieval-based prompting such as RAG and RAG ICL, context grounding was shown to improve classification performance in both single- and multi-label settings. Furthermore, we evaluated computational efficiency alongside accuracy, offering practical insights for deployment in humanitarian contexts. As such, this research contributes to a reproducible, end-to-end evaluation framework for transformer-based crisis classification and highlights the best practices for model selection, tuning, and contextualization under domain and data constraints.

7. Conclusions

By systematically evaluating the strengths and limitations of both transformer-based architectures, this study provides valuable insights into optimizing NLP models for classifying real-world news events in the context of conflict analysis. The study performed a comparative analysis of BERT and GPT for conflict-related text classification, evaluating their performance in both SL-MLG and MLC tasks. The experimental results indicate that GPT excelled in recall for MLC in the Sudan case. These findings highlight GPT’s strength in flexible multi-label classification and BERT’s reliability in well-defined, high-precision classification tasks.

In both tasks, larger LLMs consistently outperformed their smaller counterparts. Llama3.1-70B under RAG achieved the second highest F1-score in MLC, while Llama3.3-70B and Llama3.1-70B under RAG ICL achieved the highest accuracy in SL-MLG. BERT, though outpaced in recall, remained highly precise and performed strongly, achieving the highest F1-score with the hyperparameter-tuned bert-large model achieving a score of 68.90% and achieving relatively strong accuracy scores in SL-MLG. RAG ICL achieved the most accurate results in SL-MLG, whereas standard RAG produced the second-best MLC performance in some configurations, showcasing the importance of prompting strategies. This suggests that definitions help constrain outputs in structured tasks but may limit flexibility in multi-label classification.

Despite these plausible results, several challenges remain. First, handling ambiguous multi-label categories remains a challenge, especially when training data is limited or inconsistently labeled. In this study, overlapping event categories further complicated classification, making expert-defined definitions essential for guiding the model. Second, computational efficiency is a key concern, as BERT requires extensive training, and hyperparameter tuning is time intensive. GPT demands significant inference time for larger datasets, GPU acceleration is important for faster inferencing, and effective prompt engineering [14]. Third, dataset limitations, such as imbalanced category distributions and inconsistencies in human annotations, affect model performance and generalizability.

Future research should explore advanced classification techniques such as hierarchical multi-label classification, contrastive learning, and semi-supervised learning to improve performance on limited datasets with complex category structures.

Future work may also include a context-independent baseline such as FastText to better isolate the impact of contextual embeddings. While excluded in this study to maintain a focused comparison between transformer-based models, a future study on FastText could provide additional insight into the relative benefits of contextualization for conflict-related text classification.

By enabling large-scale automated classification of conflict-related articles, this approach streamlines data collection pipelines for geospatial systems and enhances the utility of unstructured text in GIS-based analysis. Incident classification directly supports structured extraction of metadata for automatic mapping, trend analysis, and early warning systems. For planners and humanitarian organizations, the ability to consistently label incidents by type allows for improved situational awareness, resource allocation, and prediction of conflict dynamics. Integration of NLP classification into GIS frameworks not only improves responsiveness but also opens pathways for predictive modeling and automatic conflict mapping using spatiotemporal patterns in labeled conflict data.

The constrained nature of the dataset, which has limited annotated examples and ambiguous multi-label categories, highlights the importance of selecting appropriate models and methods tailored to such scenarios. As LLMs continue to evolve, refining their classification capabilities for constrained, domain-specific datasets will be critical in advancing automated information retrieval for conflict monitoring and other critical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y., Z.W. and Y.M.; methodology, Z.W. and Y.M.; software, Y.M. and Z.W.; validation, Y.M.; formal analysis, Y.M.; investigation, Y.M.; resources, M.B.; data curation, Y.M., S.A., A.S.M. and T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M. and Z.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.J., Y.L., Q.L. and C.Y.; visualization, Y.M.; supervision, D.P., D.W.S.W. and C.Y.; project administration, D.P., D.W.S.W., C.Y. and D.R.; funding acquisition, D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Department of State, MITRE Inc., and NSF (1841520, 2127901).

Data Availability Statement

The Sudan incident log data can be provided upon request. The code for running the models and assessing their performance is available at https://github.com/stccenter/Comparative-Analysis-of-BERT-and-GPT-for-Classifying-Crisis-News-with-Sudan-Conflict-as-an-Example (accessed on 3 July 2025).

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the comments and advice received from MITRE and State Department colleagues while we conducted the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LLM | Large language model |

| ML | Machine learning |

| DL | Deep learning |

| NER | Named entity recognition |

| GPT | Generative pre-trained Transformer |

| BERT | Bidirectional encoder representations from Transformers |

| RAG | Retrieval-augmented generation |

| ICL | In-context learning |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

| MLC | Multi-label classification |

| SL-MLG CV | Single-label from multi-label ground truth Cross-validation |

| HP | Hyperparameter |

References

- Croicu, M. Deep Active Learning for Data Mining from Conflict Text Corpora. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.01577. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training. Available online: https://cdn.openai.com/research-covers/language-unsupervised/language_understanding_paper.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Wang, Z.; Masri, Y.; Malarvizhi, A.S.; Stover, T.; Ahmed, S.; Wong, D.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Bere, M.; Rothbart, D.; et al. Optimizing Context-Based Location Extraction by Tuning Open-Source LLMs with RAG. Int. J. Digit. Earth. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Kakkar, D.; Guan, W.; Ji, W.; Cain, J.; Lan, H.; Sha, D.; Liu, Q.; et al. Public Opinions on COVID-19 Vaccines—A Spatiotemporal Perspective on Races and Topics Using a Bayesian-Based Method. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Peng, H.; Li, J.; Xia, C.; Yang, R.; Sun, L.; Yu, P.S.; He, L. A Survey on Text Classification: From Shallow to Deep Learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2008.00364. [Google Scholar]

- Lavanya, P.; Sasikala, E. Deep Learning Techniques on Text Classification Using Natural Language Processing (NLP) In Social Healthcare Network: A Comprehensive Survey. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication (ICPSC), Coimbatore, India, 13–14 May 2021; pp. 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Pang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, X. Adaptable and Reliable Text Classification Using Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.10523. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Quintero, A.J.; Yang, C.; Ji, W. Rapid Perception of Public Opinion in Emergency Events through Social Media. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2022, 23, 04021066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufi, F. Advances in Mathematical Models for AI-Based News Analytics. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cong, P.; Lv, S. A Long-Text Classification Method of Chinese News Based on BERT and CNN. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 34046–34057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, B.; Rabbi, F.; Opdahl, A.L. Evaluating the Effectiveness of GPT Large Language Model for News Classification in the IPTC News Ontology. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 145386–145394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qu, W.; Ye, X. Selecting Between BERT and GPT for Text Classification in Political Science Research. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.05050. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Cain, J.; Salami, M.; Duffy, D.Q.; Little, M.M.; Yang, C. Adopting GPU Computing to Support DL-Based Earth Science Applications. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 2660–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, J.R.; Talukder, M.A.R.; Malakar, P.; Kabir, M.M.; Nur, K.; Mridha, M.F. Recent Advancements and Challenges of NLP-Based Sentiment Analysis: A State-of-the-Art Review. Nat. Lang. Process. J. 2024, 6, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeyemi, D.A.; Ojo, A.K. SMS Spam Detection and Classification to Combat Abuse in Telephone Networks Using Natural Language Processing. J. Adv. Math. Comput. Sci. 2023, 38, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Liu, B.; Lin, Q.; Zhao, X.; Che, C. Semantic Similarity Matching for Patent Documents Using Ensemble BERT-Related Model and Novel Text Processing Method. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.06782. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Liu, B. Deep Learning for Sentiment Analysis: A Survey. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.07883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, F. Machine Learning in Automated Text Categorization. ACM Comput. Surv. 2002, 34, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, K.; Armstrong, E.M.; Huang, T.; Moroni, D.F.; Finch, C.J. A Comprehensive Methodology for Discovering Semantic Relationships among Geospatial Vocabularies Using Oceanographic Data Discovery as an Example. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 31, 2310–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Convolutional Neural Networks for Sentence Classification. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1408.5882. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Huang, Q.; Qin, H.; Scheele, C.; Yang, C. Deep Learning for Real-Time Social Media Text Classification for Situation Awareness–Using Hurricanes Sandy, Harvey, and Irma as Case Studies. In Social Sensing and Big Data Computing for Disaster Management; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, A. Generating Sequences with Recurrent Neural Networks. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1308.0850. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan, N.; Marrone, S.; Sansone, C. Transformers in the Real World: A Survey on NLP Applications. Information 2023, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar, W.; Goswami, S.; Chakrabarti, A. A Survey on Transformers in NLP with Focus on Efficiency. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.16893. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.14165. [Google Scholar]

- Alaparthi, S.; Mishra, M. Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT): A Sentiment Analysis Odyssey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.01127. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Zhou, X.; Fan, J.; Xie, X.; Zhu, S. Can Bidirectional Encoder Become the Ultimate Winner for Downstream Applications of Foundation Models? arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.18021. [Google Scholar]

- Limsopatham, N. Effectively Leveraging BERT for Legal Document Classification. In Natural Legal Language Processing Workshop 2021; Aletras, N., Androutsopoulos, I., Barrett, L., Goanta, C., Preotiuc-Pietro, D., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 2021; pp. 210–216. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Qu, P.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, Z. Sentiment Analysis in Social Media: Leveraging BERT for Enhanced Accuracy. J. Ind. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2024, 2, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman-Khan, H.; Naeem, M.; Guarasci, R.; Bint-Khalid, U.; Esposito, M.; Gargiulo, F. Enhancing Text Classification Using BERT: A Transfer Learning Approach. Comput. Sist. 2024, 28, 2279–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. A Study on News Headline Classification Based on BERT Modeling; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 345–355. [Google Scholar]

- Bedretdin, Ü. Supervised Multi-Class Text Classification for Media Research: Augmenting BERT with Topics and Structural Features. Available online: https://helda.helsinki.fi/items/f02c65c9-f449-4fc7-a4ac-2ad23d3cea93 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Shah, M.A.; Iqbal, M.J.; Noreen, N.; Ahmed, I. An Automated Text Document Classification Framework Using BERT. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridis, C. Text Classification: Neural Networks VS Machine Learning Models VS Pre-Trained Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.21022. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI; Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; et al. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, R.; Chen, G.; Zhang, X.; Guerin, F.; Cambria, E. GPTEval: A Survey on Assessments of ChatGPT and GPT-4. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2308.12488. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Y.; Wu, B.P.; Thorne, W.; Robinson, A.; Aletras, N.; Scarton, C.; Bontcheva, K.; Song, X. Navigating Prompt Complexity for Zero-Shot Classification: A Study of Large Language Models in Computational Social Science. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2305.14310. [Google Scholar]

- Balkus, S.V.; Yan, D. Improving Short Text Classification with Augmented Data Using GPT-3. Nat. Lang. Eng. 2024, 30, 943–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yuan, W.; Fu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Hayashi, H.; Neubig, G. Pre-Train, Prompt, and Predict: A Systematic Survey of Prompting Methods in Natural Language Processing. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-Generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.10902. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.; Douze, M.; Jégou, H. Billion-Scale Similarity Search with GPUs. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.08734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, P.T.; Alsarra, S.; D’Orazio, V.J.; Heintze, D.; Khan, L.; Meher, S.; Osorio, J.; Sianan, M. ConfliBERT: A Language Model for Political Conflict. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.15060. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).