1. Introduction

With the global expansion of energy infrastructure, particularly in extreme environments, such as colder regions, there is a growing demand for line pipe steels that can perform reliably under low-temperature conditions. These line pipes play a critical role in the transportation of oil, gas, and other chemicals, making their mechanical integrity essential for preventing catastrophic failures. In cold regions, where temperatures often drop below freezing, line pipe steels must be designed to avoid brittle fracture, necessitating a high level of fracture toughness and mechanical resilience to meet stringent industry standards [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Line pipe performance is often evaluated through mechanical tests such as tensile testing, Charpy impact testing, and drop weight tear testing (DWTT). DWTT is particularly crucial for line pipe operating in low temperatures as it provides insight into a material’s resistance to a propagating brittle fracture and thus catastrophic failure [

2]. Another significant challenge in maintaining the integrity of line pipe steels is the impact of hydrogen-related damage, including hydrogen-induced cracking (HIC) and hydrogen embrittlement (HE), both of which can severely degrade the mechanical properties of steels in low-temperature environments [

5]. This consideration is especially important in the context of sour service line pipes, where exposure to hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) can exacerbate hydrogen damage. As a result, the development of line pipe steels with enhanced DWTT performance and HE resistance is a key priority in the industry [

2,

6].

The thermomechanical controlled process (TMCP) is a highly effective technique for refining grain size and optimizing the overall structure of steel [

7]. This process is especially useful for precisely controlling grain orientations and morphologies. This control can then be used to improve environmentally assisted degradation resistance in cold environments. Extensive research has been conducted on the influence of TMCP parameters on the properties of line pipe steel [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Roughing and finishing (R/F) rolling reductions are crucial TMCP parameters that significantly influence the microstructure, which subsequently impacts DWTT outcomes [

15,

16]. During the roughing rolling phase, higher reduction levels facilitate substantial grain refinement, breaking down larger grains and creating a more uniform and refined microstructure. This refinement enhances toughness by increasing grain boundaries, which act as obstacles to crack propagation, thus improving DWTT performance [

15]. In the F rolling stage, additional deformation is introduced to further refine and align the microstructure, particularly affecting the grain size and texture. The F reduction is essential for promoting favorable texture components, like {332}〈113〉 and gamma (γ) fiber, which enhance DWTT results by improving the material’s ability to arrest cracks [

17,

18]. By carefully optimizing these parameters, it is possible to obtain a diverse range of steel microstructures, including ferrite, as well as minor constituents such as pearlite and bainite [

11,

15]. These tailored microstructures contribute significantly to the steel’s ability to withstand the challenging conditions associated with low-temperature service, thereby improving its overall performance and durability.

As the temperature decreases, the toughness of the steel diminishes until it reaches the ductile-to-brittle transition temperature (DBTT), at which point brittle fracture becomes more likely. Understanding and managing the fracture behavior of line pipe steel is critical for ensuring line pipe safety. This behavior is intrinsically linked to factors such as microstructure, crystallographic orientations, alloying elements, and precipitates [

19,

20]. Recent studies have shown that refining steel grains improves both the absorbed energy during low-temperature DWTT and the critical shear area percentage of 85% [

21]. Grain refinement is often achieved by rolling the steel in the non-recrystallization region followed by rapid cooling, a process that enhances strength through the Hall–Petch relation [

22,

23]. Some research [

24,

25] has further demonstrated that smaller grains, obtained via ultrafast cooling, significantly contribute to increased strength and toughness in line pipe steel. A larger ferrite grain size generally increases the ductile-to-brittle transition temperature (DBTT) in pipeline steels, leading to a greater risk of brittle fracture at low temperatures. This is because larger grains provide longer, unobstructed paths for crack propagation [

26]. Conversely, smaller grains provide more boundaries that can deflect and stop a crack from propagating, which requires more energy and shifts the DBTT to a lower value, improving toughness [

27]. However, recent studies [

28,

29] showed an optimum range of grain size improved toughness at low temperature. In addition to grain size reduction, controlling grain orientation and phase composition could further enhance fracture toughness [

24,

30,

31]. Additionally, variations in dislocation density introduced during TMCP can significantly affect both the strength and toughness, influencing DWTT outcomes [

32]. Balancing dislocation density is therefore crucial to limiting crack initiation and propagation while improving mechanical performance at low temperatures. A higher dislocation density usually increases the steel’s yield and tensile strength. This happens because dislocations impede each other’s movement and make plastic deformation more difficult, thereby raising strength [

33]. On the other hand, in DWTT, high dislocation density can contribute to crack initiation or propagation if the steel cannot accommodate further plastic deformation. While there is substantial evidence supporting the modification of processing conditions to achieve the desired microstructure or texture, achieving homogeneous grain orientation across the steel thickness continues to be a challenge in hot-rolled plates [

34]. Duan et al. [

35] found that a fine acicular ferrite, achieved through a fast cooling rate, resulted in higher DWTT absorbed energy and a lower DBTT. In contrast, coarse polygonal ferrite, produced through air cooling, exhibited lower absorbed energy and higher DBTT. Their investigation also revealed that the fracture surface with the highest fraction of grains oriented with the

cleavage plane absorbed the least impact energy [

35]. Moreover, when the per-pass reduction in the final roughing pass exceeded 15%, a fine, uniform microstructure of acicular ferrite was achieved, resulting in superior low-temperature fracture toughness [

36]. These findings emphasize the need to refine grain size while carefully controlling grain orientation and secondary phases to optimize line pipe steel performance in low-temperature environments. While the effect of microstructure on mechanical properties has been widely studied, the influence of crystallographic texture and its key contributing factors remain underexplored.

Microstructure control has been reported as a critical factor in mitigating hydrogen-related degradation in line pipe steels. Previous studies show that a higher fraction of acicular ferrite and granular bainite, combined with the absence of segregation zones, can significantly enhance HIC resistance [

37,

38]. Additionally, recent studies [

39] indicate that HIC tends to propagate more easily through grains with certain preferential orientations, such as

,

, and

(ND: Normal direction). Conversely, crystallographic orientations like

,

, and

have been shown to significantly improve HIC resistance by reducing intergranular crack paths [

40,

41]. This improvement is attributed to the increased number of coincidence site lattice (CSL) grain boundaries and low-angle grain boundaries (LAGBs) [

9]. Non-metallic inclusions (NMIs) are crucial in both the initiation and growth of HIC due to their influence on localized stress fields and their hydrogen trapping capabilities [

42,

43]. The chemical composition of NMIs affects their interaction with hydrogen. In particular, oxide and sulfide inclusions have been observed within the crack paths of line pipe steels, indicating their contribution to crack propagation [

8,

44].

In this work, the influence of controlled thermomechanical rolling, through different combinations of roughing and finishing reductions, on the microstructure, texture, low-temperature toughness, and hydrogen-induced damage resistance of X70 line pipe steels was systematically investigated. While the steels exhibited similar phase constituents, subtle variations in grain size and morphology prompted a deeper examination of texture components, secondary phases, and GND-related features. The study aimed to identify which metallurgical factors most strongly govern DWTT performance and susceptibility to hydrogen cracking and blistering, and to determine how their optimization can enhance low-temperature serviceability. By integrating SEM, EBSD, and XRD analyses with quantitative evaluation of microstructural and textural contributions, this work provides a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms that control toughness and hydrogen damage in line pipe steels and offers guidance for improved performance of pipeline steels.

2. Materials and Methods

This study processed line pipe steels intended for sweet oil and gas to assess the impact of different roughing and finishing (R/F) deformations on the resulting microstructure, texture, and properties. The steels came from the same slab that was industrially cast (i.e., same chemistry), targeting an X70 grade as in

Table 1 and was then subsequently pilot-scale rolled as presented in previous research [

45] (From Interpro Pipe and Steel, Regina, SK, Canada). The three steel plates, part of the line pipe steel grade X70 group and designated as I-50, I-60, and I-70, shared the same microalloying composition as detailed in

Table 1. In the sample codes, the letter “C” represents the centerline, while “Q” denotes the quarterline.

Table 2 presents three distinct multi-pass rolling schedules designed to develop different textures with samples designated as I-50, I-60, I-70 by the approximate roughing reduction applied. Notably, I-70 steel had the highest roughing (R) reduction, while I-50 steel had the lowest. In contrast, finishing (F) reduction was highest in I-50 steel, medium in I-60, and lowest in I-70 steel. It is important to highlight that despite the variations in R/F reductions, all steels maintained a total thickness reduction of 90%. Other TMCP conditions (reheating, accelerated cooling, coiling simulations, etc.) were kept the same.

Microstructure and texture evaluations were conducted on all line pipe steel specimens. Samples were prepared with dimensions of 20 mm (RD: Rolling direction) × 20 mm (TD: Transverse direction) × 2 mm (ND: Normal direction), machined from both the quarterline and centerline of the thickness (See

Figure 1). In the sample codes, the letter “C” represents the centerline, while “Q” denotes the quarterline through the thickness of the steel. Microstructure and crystallographic texture of the studied steels were examined using a Hitachi SU6600 FESEM equipped with EBSD and connected to a computer running AZTEC 2.0 software (From Headquarters Hitachi High-Tech Canada, Toronto, ON, Canada). EBSD analysis was performed to characterize ferrite grain size, grain orientation, and texture components. The specimens were first prepared for microscopy and then subjected to additional polishing using a Buehler VibroMet 2 vibratory polisher with a 0.04 μm colloidal silica suspension (From Buehler in Lake Bluff, IL, USA) for 6–10 h following diamond polishing. After polishing, samples were rinsed with deionized water and ethanol, thoroughly dried, and mounted in a vacuum chamber for EBSD imaging. Measurements were conducted at an accelerating voltage of 30 kV with a step size of 0.14 μm over an area of 1200 × 900 μm

2. The collected EBSD data was processed using Channel 5 software (Version 5.1, Oxford Instruments, High Wycombe, UK), recorded with AZTEC 2.0, and subsequently post-processed using HKL Project Manager software.

Drop weight tear testing is recognized for providing more accurate results compared to the conventional Charpy Impact test [

46]. The DWTTs were conducted following API 5L [

47] to evaluate the full-scale fracture response of each line pipe steel and the shear area percentage and absorbed energy were recorded. The DWTT specimens were full-thickness samples, measuring 12 inches (~305 mm) in length by 3 inches (~76 mm) in width, machined along the rolling direction with a notch oriented towards the transverse direction, according to

Figure 1 schematic. According to the test standard [

47], a minimum average shear area percentage of 85% is required for a test to be considered successful. Initial tests were conducted at −45 °C for all steel samples, followed by testing at −60 °C. To ensure reproducibility, a minimum of two samples were tested at each temperature.

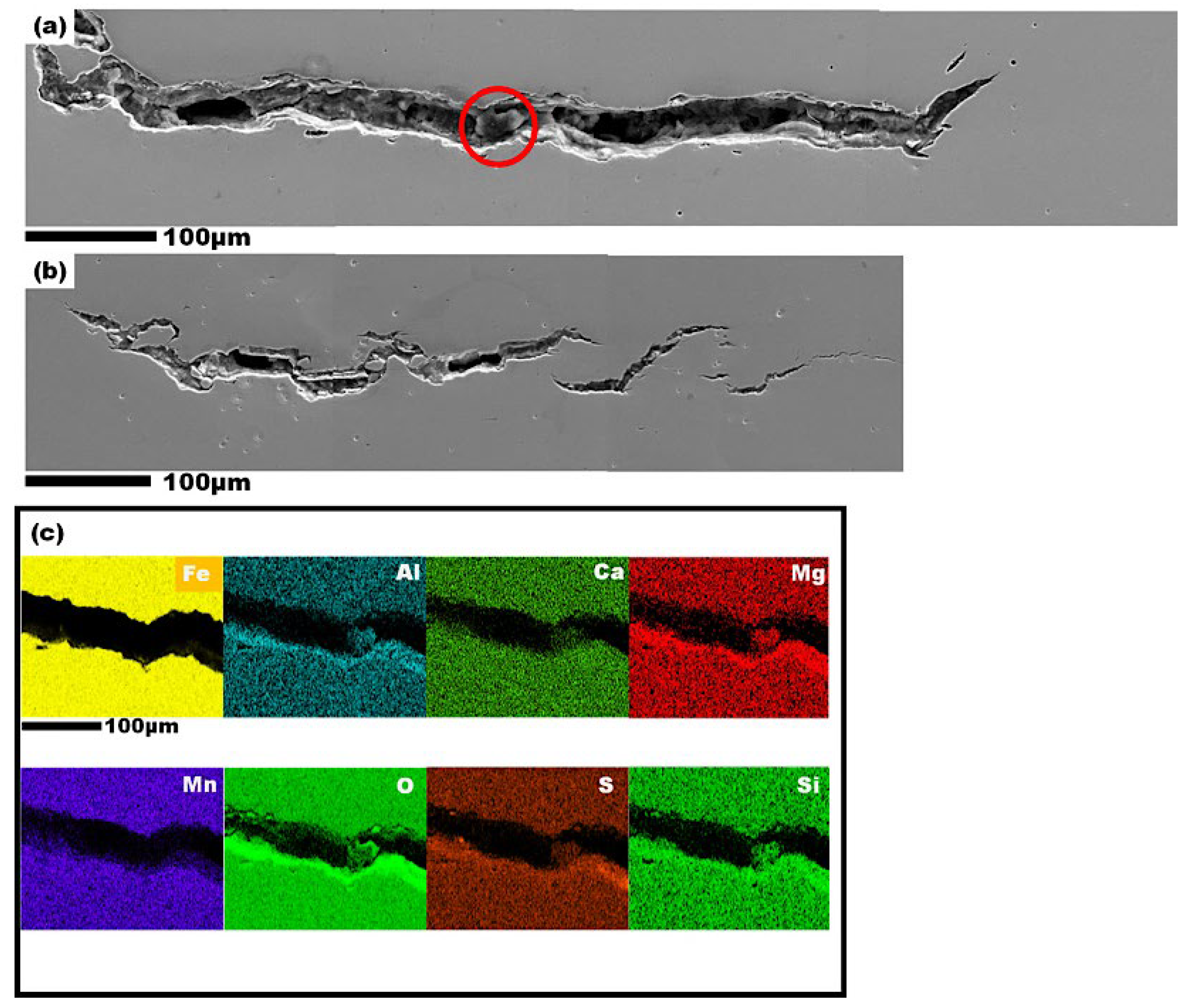

The effect of hydrogen on the degradation of line pipe steels was evaluated using the electrochemical charging technique. For each steel, specimens were immersed in a single cell containing 0.2 M sulfuric acid and 3 g/L ammonium thiocyanate (Both from Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada) at a current density of 20 mA/cm2. During electrolysis, hydrogen evolves at the steel surface and oxygen is generated at the platinum electrode. Ammonium thiocyanate promotes hydrogen entry by acting as a cathodic poison: SCN− ions adsorb on the steel surface, suppress H2 bubble formation, increase the coverage of adsorbed hydrogen (H_ads), and facilitate its absorption into the lattice (Hads → Hlattice). Following hydrogen charging, specimens were rinsed with alcohol and analyzed for surface blisters and internal cracks. The total number of hydrogen-induced defects, along with the average crack length and blister area, were recorded for each sample. Specimens were then sectioned along the RD–ND plane to assess internal hydrogen-induced cracks, followed by polishing according to the previously described procedure. SEM imaging was subsequently used to evaluate the number and dimensions of internal cracks.