Effects of Solid Solution Heat Treatment on the Corrosion Behavior of 800H Used in Fourth-Generation Nuclear Power Generators

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Samples

2.2. Experimental Procedures

3. Results

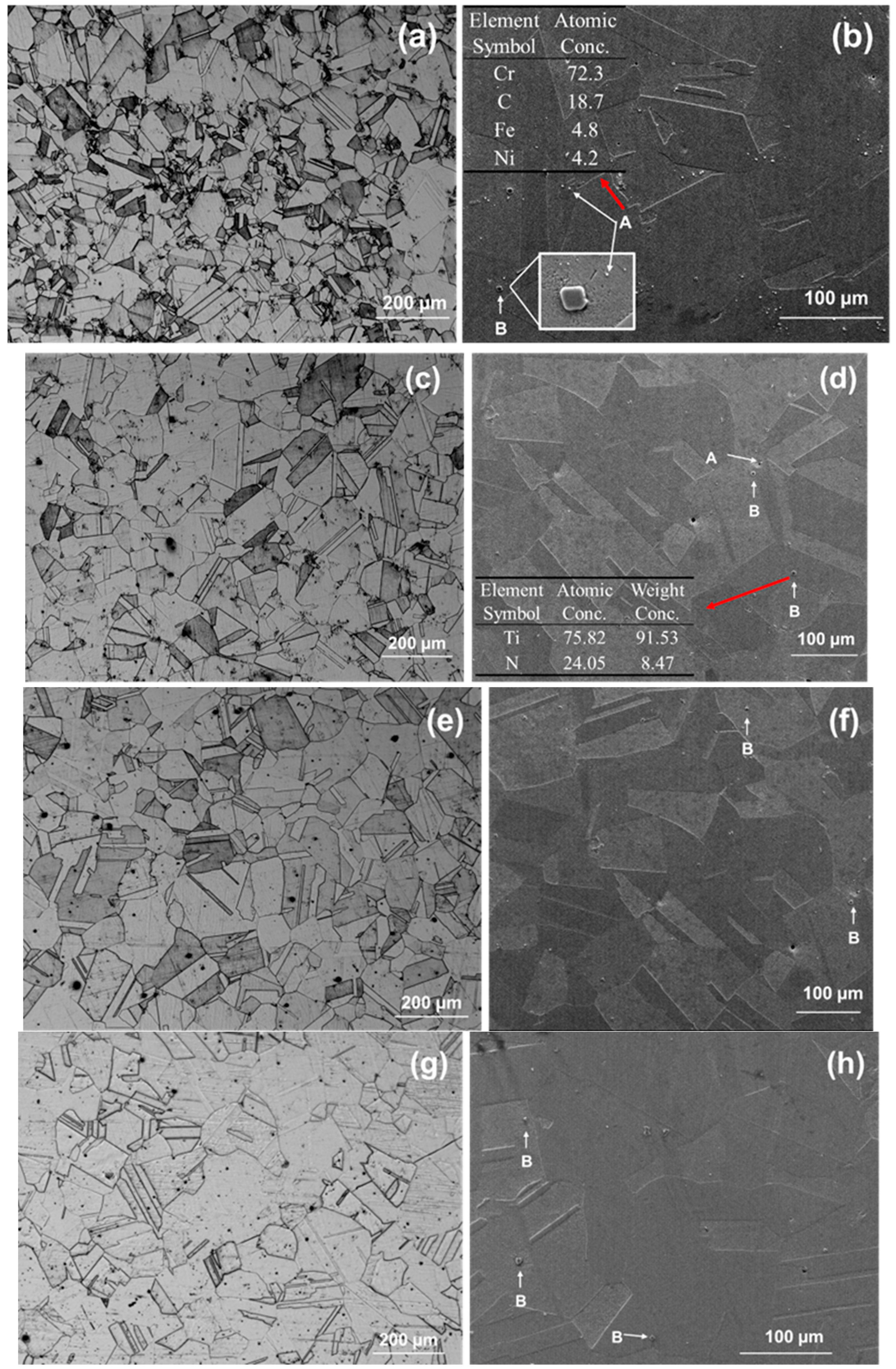

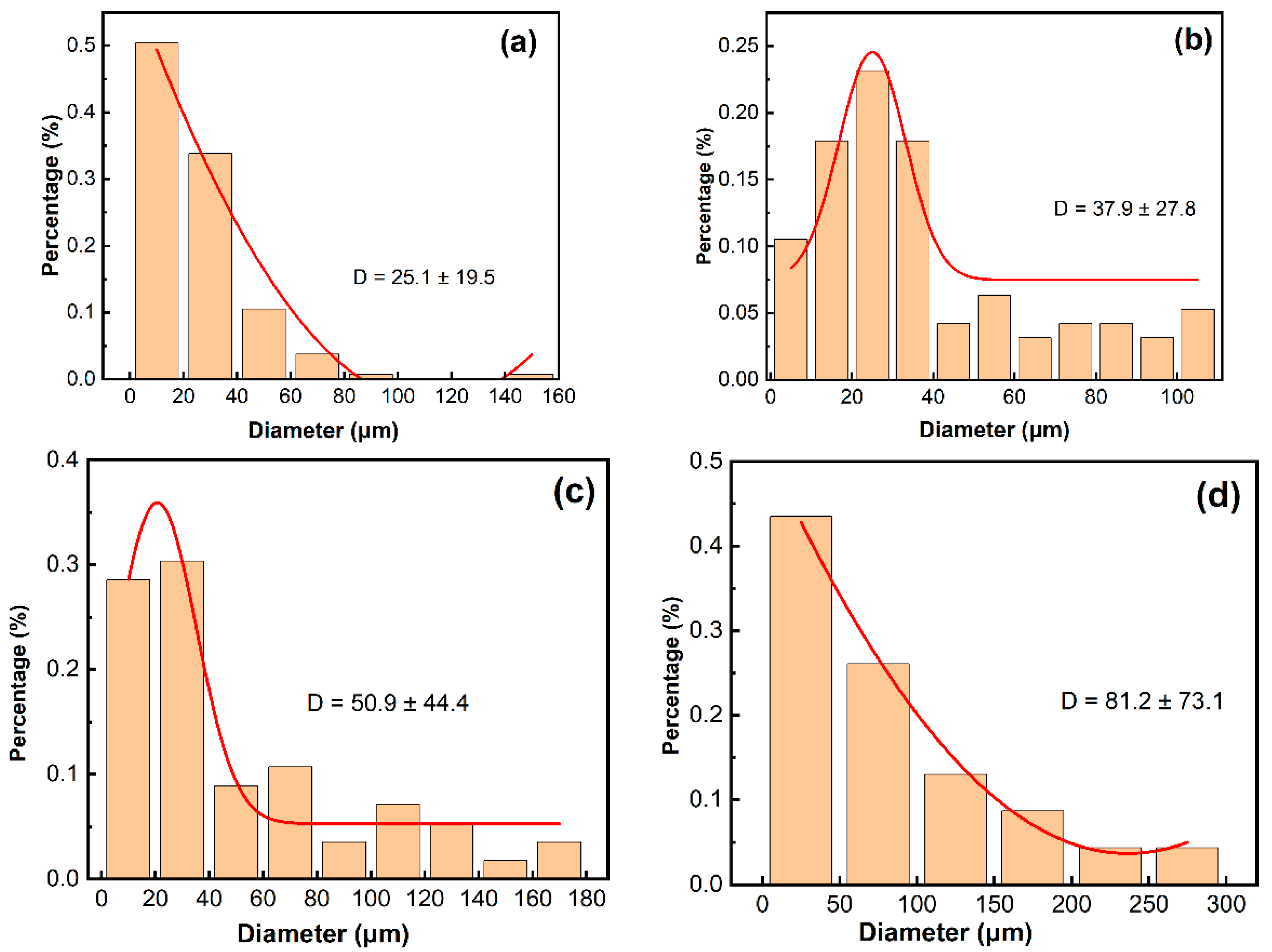

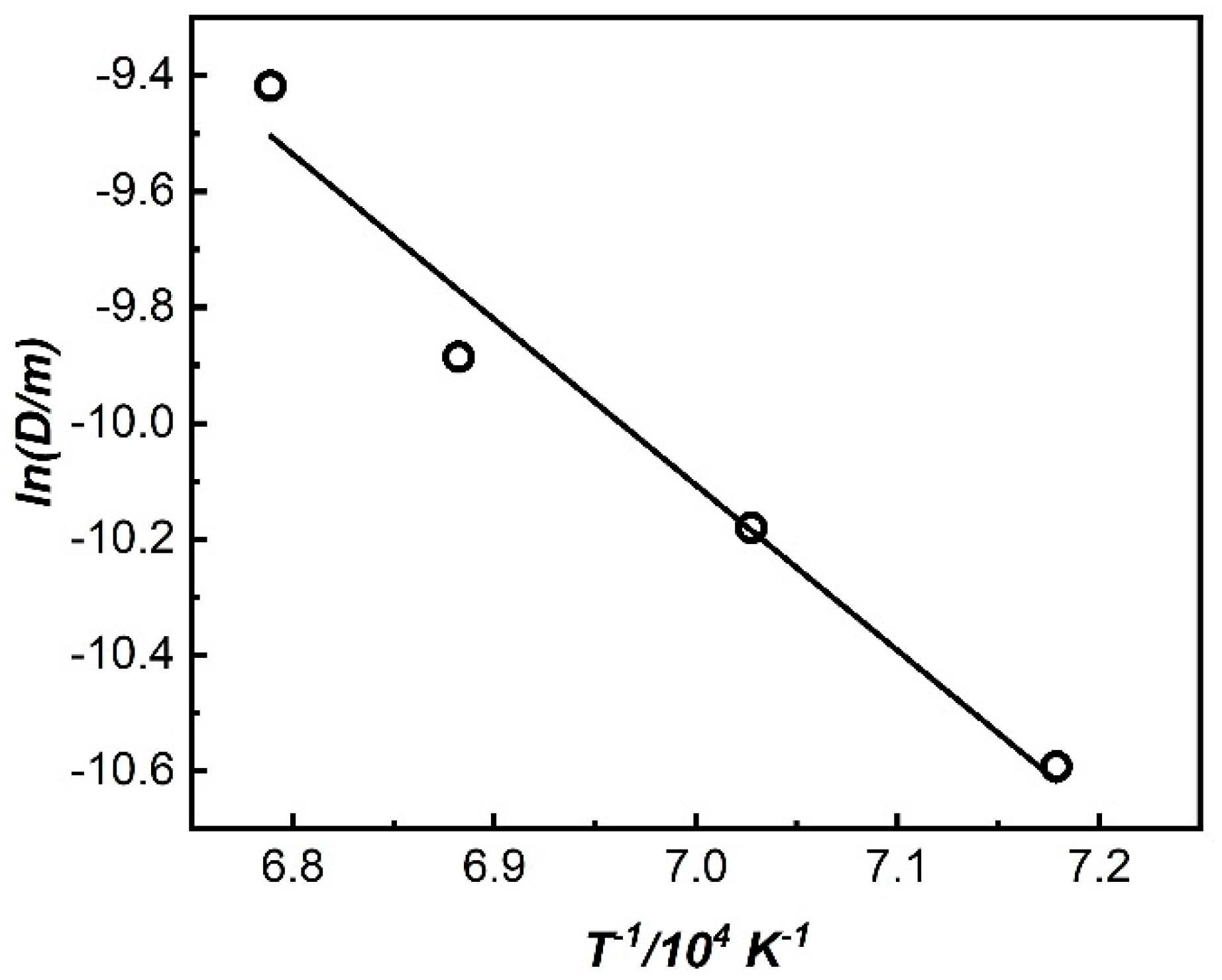

3.1. The Microstructure of the 800H Alloy After Different Solid Solution Heat Treatments

3.2. The Electrochemical Corrosion Behavior of the 800H Alloy After Different Solid Solution Heat Treatments

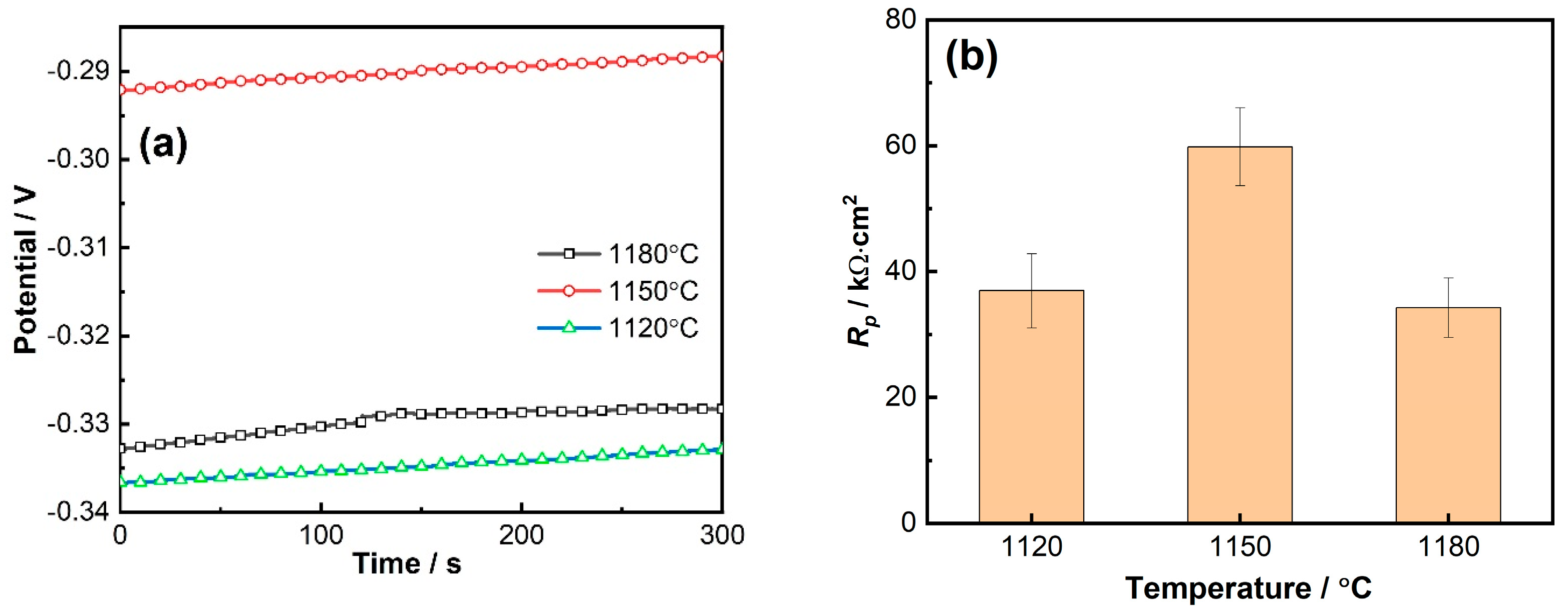

3.2.1. Corrosion Potential and Linear Polarization Resistance Results

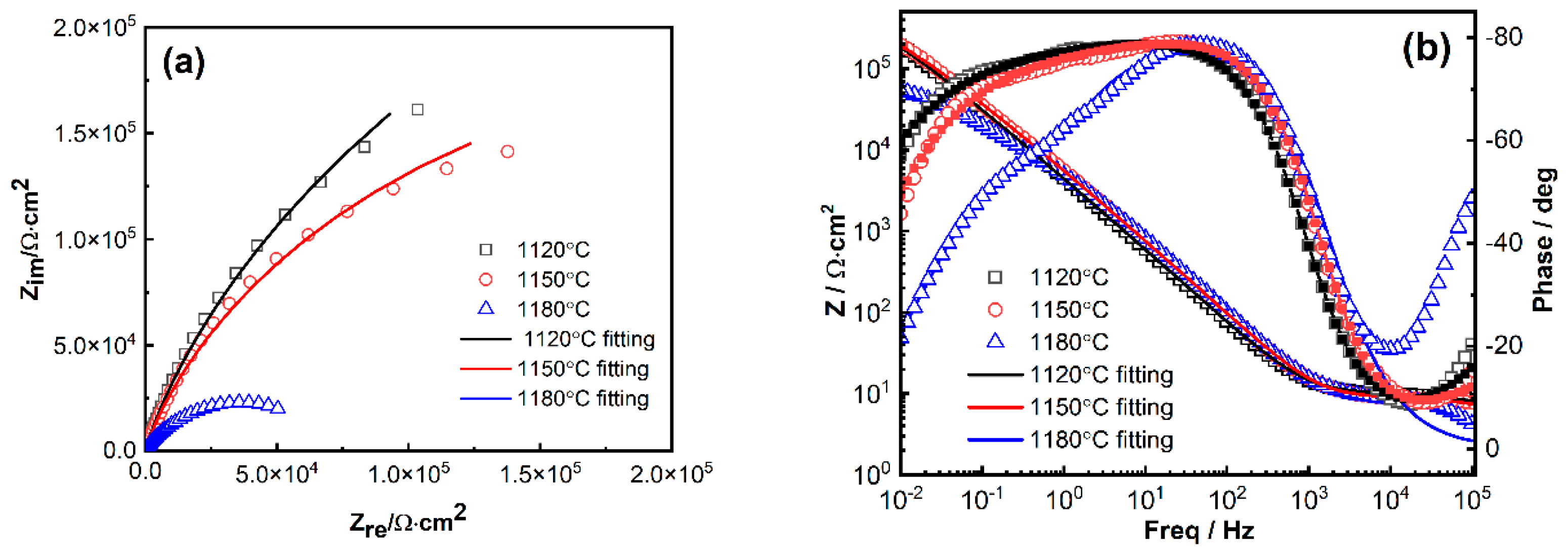

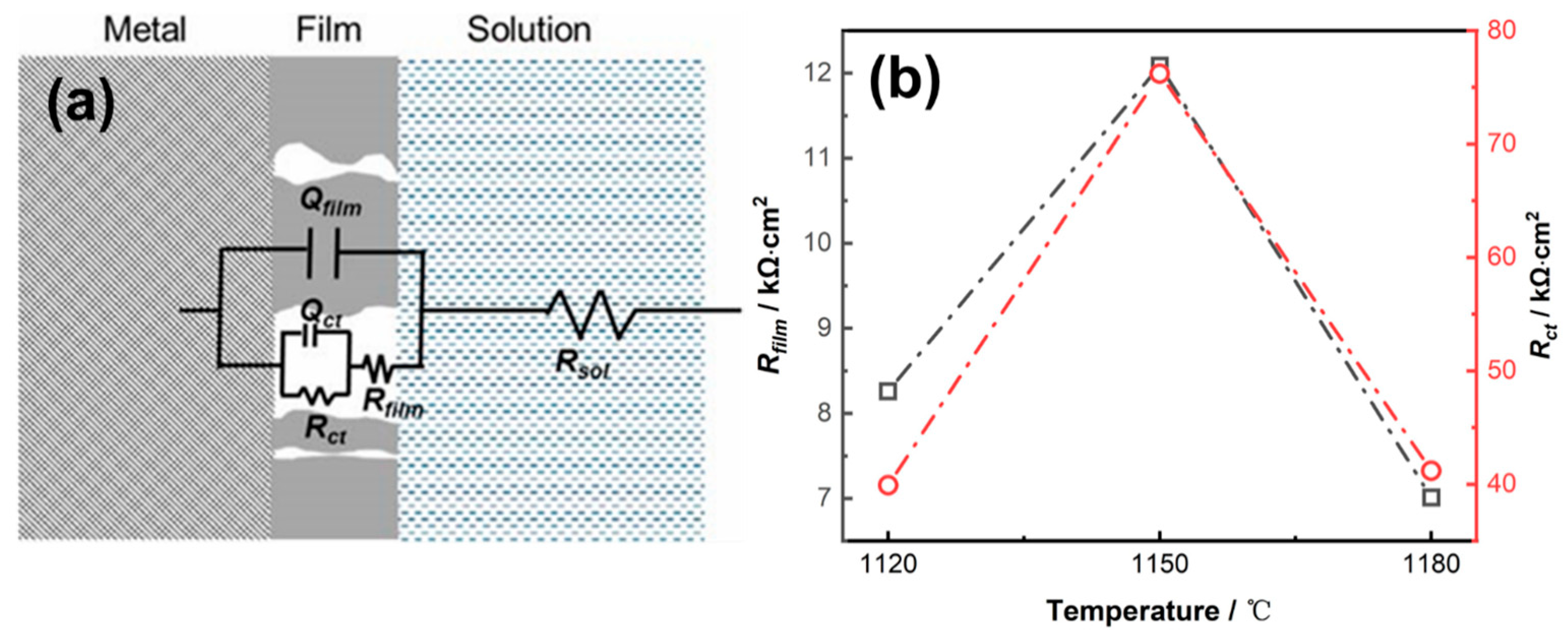

3.2.2. EIS Results

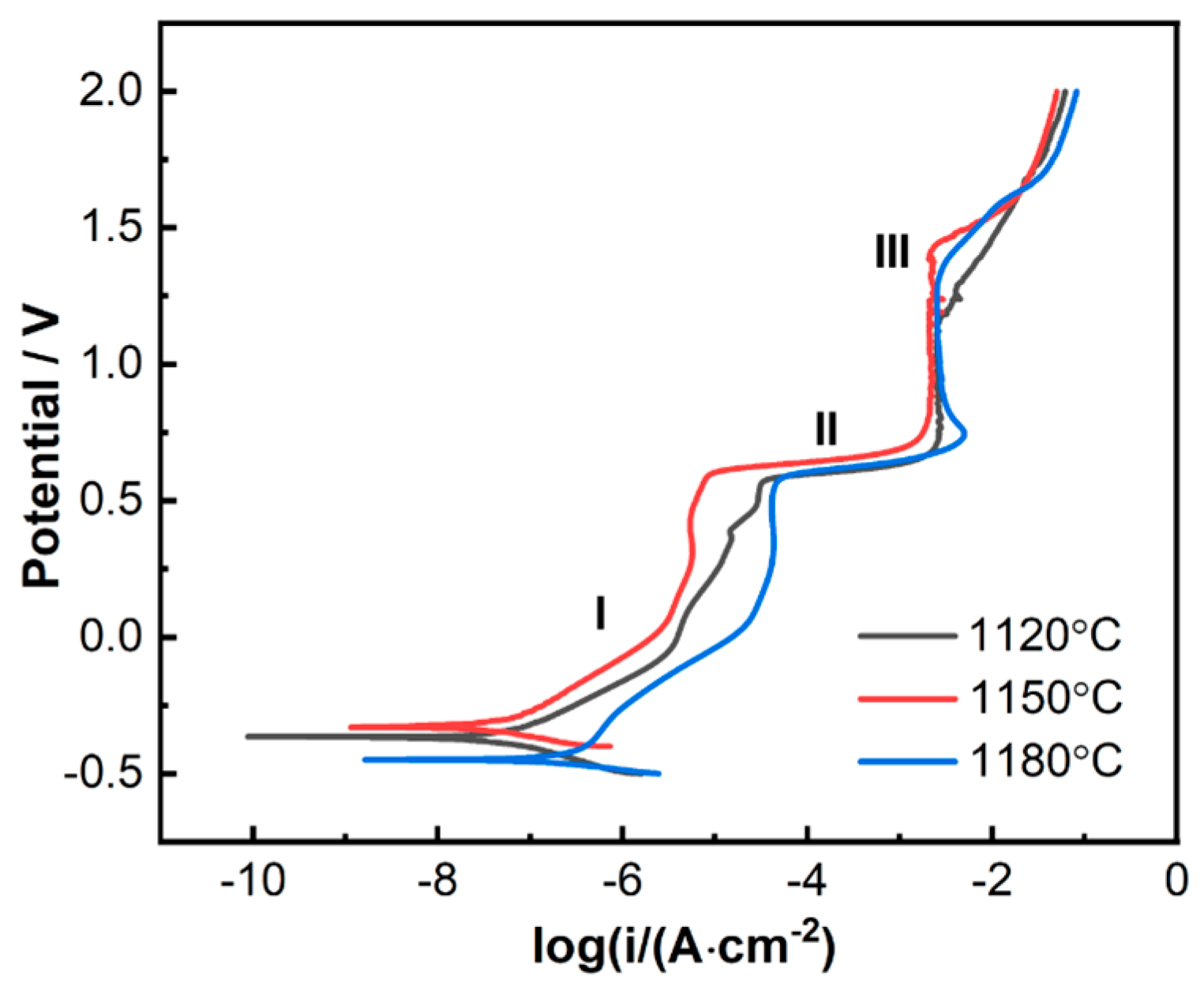

3.2.3. Anodic Polarization Curves

4. Discussion

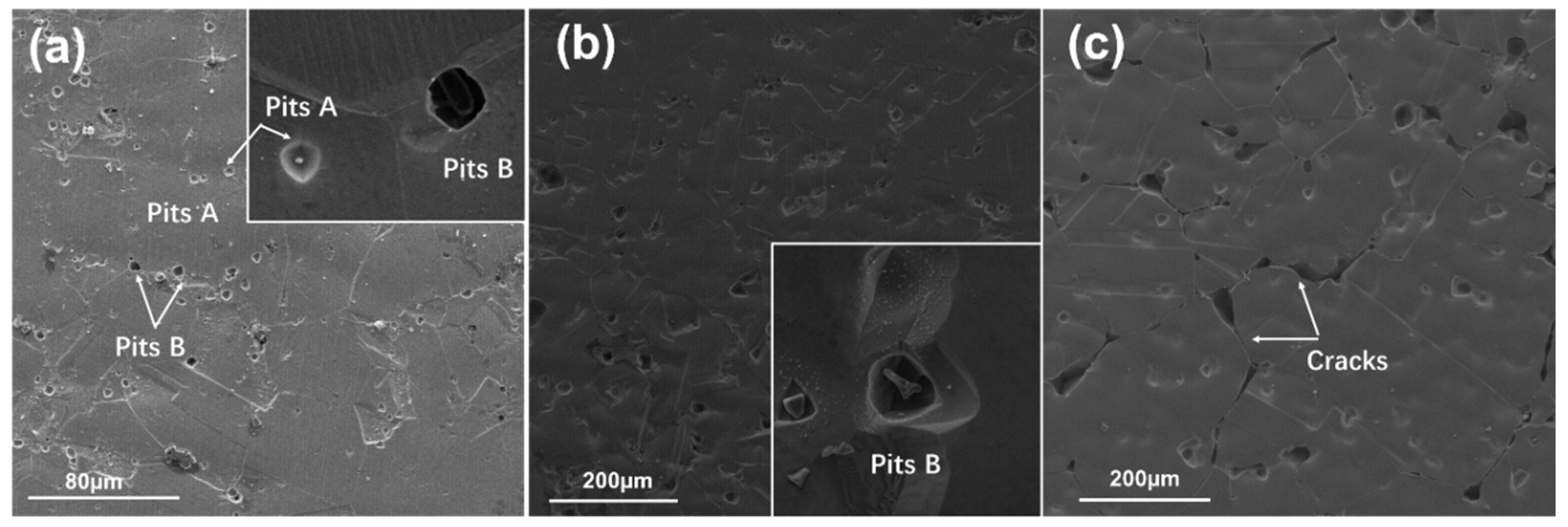

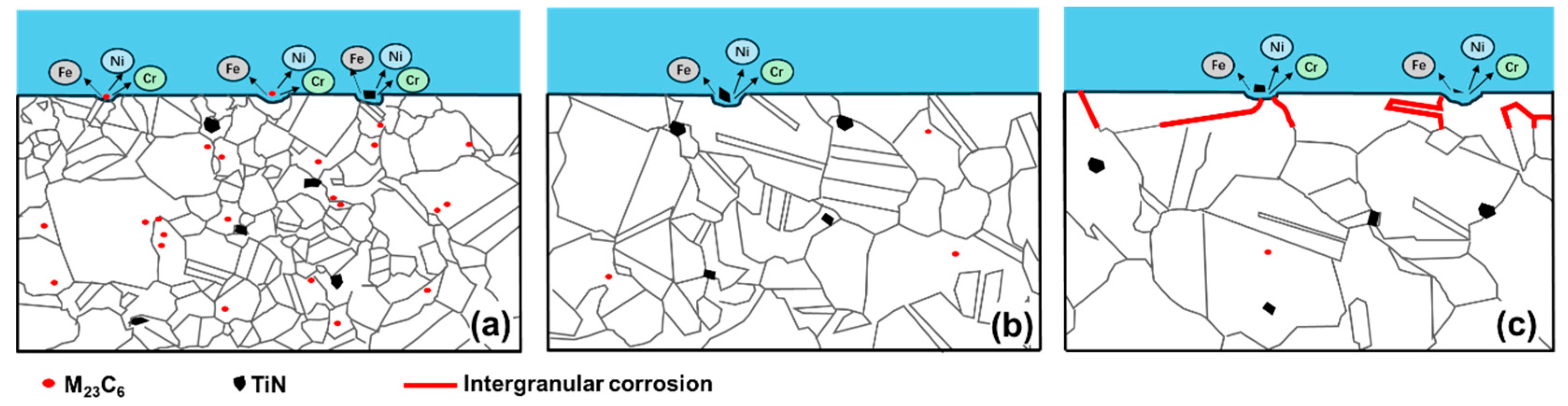

4.1. Corrosion Initiated by the Second Phase

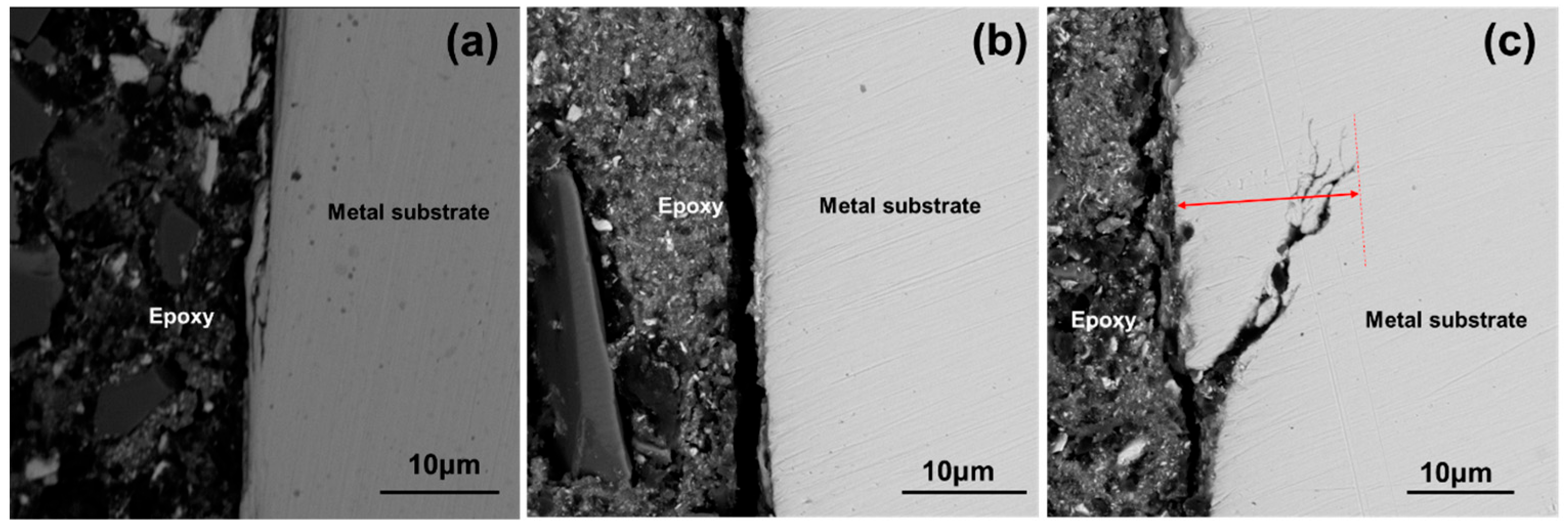

4.2. Intergranular Corrosion Test Results

5. Conclusions

- Solid solution at 1120 °C was insufficient heat treatment. The 800H alloy showed uneven growth of grains and undissolved Cr-carbides. Solid solution at 1150 °C resulted in even growth of grains with the best grain uniformity. Cr-carbides dissolved into the matrix and a good amount of twin boundaries was observed. Solid solution at 1180 °C and above resulted in overheating of the 800H alloy, and grain size significantly increased with straight grain boundaries.

- Electrochemical corrosion tests demonstrated that the 800H alloy exhibited the best corrosion resistance after heat treatment at 1150 °C. The 800H alloy showed pseudo-passivation, transpassivation, and repassivation (III) during the anodic polarization. This corresponded to the multi-reactions involved in the corrosion process.

- For 800H heat treated at 1120 °C, the widely distributed Cr-carbides and TiN inclusions formed galvanic-type corrosion cells within the matrix and resulted in corrosion pit initiation. In comparison, 800H heat treated at 1150 °C demonstrated less corrosion attack due to the dissolved Cr-carbides. However, as the solid solution temperature increased to 1180 °C, IGC sensitivity increased and IGC became the dominant failure form.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ecorr | Corrosion potential |

| OCP | Open circuit potential |

| Rp | Linear polarization resistance |

| EIS | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

References

- Lake, J.A. The fourth generation of nuclear power. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2002, 40, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Guan, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Current status and trends of nuclear energy under carbon neutrality conditions in China. Energy 2025, 314, 134253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Dongxu, J.; Jahan, N.; Salvatores, M.; Zhao, J. Design concepts of supercritical water-cooled reactor (SCWR) and nuclear marine vessel: A review. Prog. Nucl. Energy (N. Ser.) 2020, 124, 103320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Lin, Y.; Si, Y.; Huang, C.; Yang, J.; Huang, B.; Li, W. Present situation and future prospect of renewable energy in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatone, O.S.; Meindl, P.; Taylor, G.F. Steam generator tube performance: Experience with water-cooled nuclear power reactors during 1983 and 1984. Eng. Phys. Environ. Sci. 2009, 137261381. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:137261381 (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Tian, Z.X.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.L.; Zhang, D.L.; Tian, W.X.; Qiu, S.Z.; Su, G.H. Experimental investigation on the heat transfer performance of high-temperature potassium heat pipe for nuclear reactor. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2021, 378, 111182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, P.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, T.; Liu, P.; Peng, F.; Yang, L. Eco-friendly epoxidized Eucommia ulmoides gum based composite coating with enhanced super-hydrophobicity and corrosion resistance properties. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 214, 118523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z. Selecting the proper material for a grain loss sensor based on DEM simulation and structure optimization to improve monitoring ability. Precis. Agric. 2021, 22, 1120–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Swindeman, R. A Review of Alloy 800Hfor Applications in the Gen IV Nuclear Energy Systems. In Proceedings of the ASME 2010 Pressure Vessels and Piping Division/K-PVP Conference, Bellevue, WA, USA, 18–22 July 2010; Volume 6, pp. 821–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Swindeman, R. Status of Alloy 800H in Considerations for the Gen IV Nuclear Energy Systems. J. Press. Vessel Technol. 2014, 136, 054001–054012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Rakotojaona, L.; Allen, T.L.; Nanstad, R.K.; Busby, J.T. Microstructure optimization of austenitic alloy 800H (Fe-21Cr-32Ni). Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 2755–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, K.; Arun Kumar, S.; Tamilmannan, K.; Arivazhagan, B. Metallurgical characterizations and mechanical properties on friction welding of Incoloy 800H joints. J. Mater. Res. 2016, 31, 2173–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Han, E.; Wei, K. Corrosion behavior of nuclear grade alloys 690 and 800 in simulated high temperature and high pressure primary water of pressurized water reactor. Acta. Metall. Sin. 2012, 48, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Han, E.; Wei, K. Corrosion behavior for Alloy 690 and Alloy 800 tubes in simulated primary water. Corros. Sci. 2013, 67, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, R.S.; Jagannath; Dey, G.K.; De, P.K. Characterization of microstructure and corrosion properties of cold worked Alloy 800. Corros. Sci. 2006, 48, 2711–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Li, W.; Cota-Sanchez, G. Mechanical property and microstructure characterization of incoloy 800H alloy and its welds after corrosion testing in high temperature steam. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2022, 398, 111970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Dong, H.; Wang, M.; Jiang, X.C.; Ma, Y.C.; Liu, G.M.; Sun, S.H.; Qi, A.Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.Y. Microstructural evolution and mechanical behavior of 800H alloy for control rods in HTGRs under long-term thermal exposure. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 3969–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Sauzay, M.; Cui, Y.; Bonnaille, P. Theoretical and experimental study of creep damage in alloy 800 at high temperature. MSE A 2021, 813, 140953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulger, M.; Mihalache, M.; Ohai, D.; Fulger, S.; Valeca, S.C. Analyses of oxide films grown on AISI 304L stainless steel and Incoloy 800HT exposed to supercritical water environment. J. Nucl. Mater. 2011, 415, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, R.; Li, D.; Dai, Q.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Y. Oxidation resistance of alloy 800H at elevated temperature. Trans. Mater. Heat Treat. 2012, 33, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L.; Allen, T.R.; Yang, Y. Corrosion behavior of alloy 800H (Fe–21Cr–32Ni) in supercritical water. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, H.; Du, B.; Li, H.; Yin, H.; He, H.; Ma, T. Effect of impurity ratios on the high-temperature corrosion of Inconel 617 and Incoloy 800H in impure helium. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2023, 189, 109836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Sun, D.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, K.L.; Andresen, P. Investigation on the corrosion behavior of Alloy 800H at various levels of deformation. Corros. Sci. 2023, 212, 110926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, S.; Liu, Z.; Dang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, X. Effects of cold work on the corrosion behavior of Alloy 800Hexposed to aerated supercritical water. J. Nucl. Mater. 2022, 559, 153408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, C.D.; Qiao, C.-Y.P. Microstructural investigation of the weld HAZ in a modified 800H alloy. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 1994, 116, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; He, Y.; Peng, F.; Liu, Y. Influences of second phase particle precipitation, coarsening, growth or dissolution on the pinning effects during grain coarsening processes. Metals 2023, 13, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Ding, Y.; Xu, J.; Gao, Y.; Chu, C.; Hu, Y.; Chen, D. Grain boundary engineering activated by residual stress during the laser powder bed fusion of Inconel 718 and the electrochemical corrosion performance. Mater. Charact. 2023, 204, 113160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wei, A.; Tong, X.; Lin, J.; Jin, L.; Zhong, X.; Wang, D. Improvement of the anti-corrosion property of twinning-induced plasticity steel by twin-induced grain boundary engineering. Mater. Lett. 2018, 211, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.P.; Makineni, S.K.; Gault, B.; Kawano-Miyata, K.; Taniyama, A.; Zaefferer, S. Precipitation formation on ∑5 and ∑7 grain boundaries in 316L stainless steel and their roles on intergranular corrosion. Acta Mater. 2021, 210, 116822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Ofori-Opoku, N.; Prudil, A.; Welland, M. Atomistic modeling of Σ3 twin grain boundary in alloy 800H. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2022, 212, 111573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Wang, J. Effect of grain size and grain boundary type on intergranular stress corrosion cracking of austenitic stainless steel: A phase-field study. Corros. Sci. 2024, 241, 112557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Zheng, R.; Yuan, C.; Yang, G.; Shi, C.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z. Effect of grain size on the corrosion behavior of fully recrystallized ultra-fine grained 316L stainless steel fabricated by high-energy ball milling and hot isostatic pressing sintering. Mater. Charact. 2021, 174, 110995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM A688/A688M-18; Standard Specification for Seamless and Welded Austenitic Stainless Steels Feedwater Heater Tubes. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- GB/T 15260-2016; Corrosion of Metals and Alloys-Test Methods for Intergranular Corrosion of Nickel Alloys. State Administration for Market Regulation and Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2016. Available online: https://openstd.samr.gov.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=B2D8A75A1208603AA76E0DD1A5A8C344 (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Huang, Y.; Dai, Q.; Li, D.; Cheng, X.; Tao, Y.; Liu, Y. Effect of solution treatment on microstructure and hardness of 800H alloy. Heat Treat. Met. 2012, 37, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Qiu, Y.; LI, D.; Dai, Q.; Gao, S.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Gao, P.; Wang, G. Study on Welding Properties of Alloy 800H. Hot Work. Technol. 2013, 42, 154–156. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G. Research on Welding Thermal Simulation of Fe-Ni Based Austenitic Steels. Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H.; Song, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, B.; Ji, X. Effect of solution treatment on microstructure mechanical property of Inconel 690. J. Iron Steel Res. 2009, 21, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, G.T. Grain-boundary migration and grain growth. Met. Sci. J. 1973, 8, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Wang, Q.; Long, F. Microstructure evolution of alloy 800H during cold rolling and subsequent annealing. Metals 2024, 14, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Alfantazi, A.; Schaller, R.; Asselin, E. Localised instability of titanium during its erosion-corrosion in simulated acidic hydrometallurgical slurries. Corros. Sc. 2020, 174, 108816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Asselin, E. Communication-The Galvanic Effect on the Under-Deposit Corrosion of Titanium in Chloride Solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 071512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, F.; Wang, J.; Han, E.; Ke, W. Influences of tin inclusion on corrosion and stress corrosion behaviors of alloy 690 tube in high temperature and high pressure water. Acta Metall. Sin. 2011, 47, 847–852. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, R.S.; Tewari, R.; De, P.K. Effects of heat-treatment on the extent of chromium depletion and caustic corrosion resistance of Alloy 690. Corros. Sci. 2007, 49, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Yao, H. The Relation Between the Resistance of IGA and IGSCC and the Chromium Depletion of Alloy 690. Corrosion 1990, 46, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, J.J.; Yu, G.P.; Tsai, C.H.; Liu, M.N.; Yao, S.C. The effects of heat treatment on the chromium depletion, precipitate evolution, and corrosion resistance of INCONEL alloy 690. Metall. Trans. A 1989, 20, 2057–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.Y.; Hu, W.F.; Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.K.; Wang, P.; Yang, J.H.; Wang, X.Y.; Gu, J.F.; Lu, J. Improving the intergranular corrosion resistance of austenitic stainless steel by high density twinned structure. Scr. Mater. 2017, 130, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokita, S.; Kokawa, H.; Kodama, S.; Sato, Y.S.; Sano, Y.; Li, Z.; Feng, K.; Wu, Y. Suppression of intergranular corrosion by surface grain boundary engineering of 304 austenitic stainless steel using laser peening plus annealing. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 25, 101572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Temperature/ °C | Rsol /Ω·cm2 | Qfilm-Y0 S·sn/cm−2 | Qfilm-n (0 < n < 1) | Rfilm /kΩ·cm2 | Qi-Y0 S·sn/cm−2 | Qi-n (0 < n < 1) | Rct /kΩ·cm2 | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1120 °C | 9.371 | 5.139 × 10−5 | 0.8457 | 8.26 | 4.911 × 10−5 | 0.6311 | 39.9 | 0.00602 |

| 1150 °C | 10 | 3.173 × 10−5 | 0.646 | 12.09 | 2.106 × 10−5 | 0.9338 | 76.2 | 0.03967 |

| 1180 °C | 7.723 | 3.112 × 10−5 | 0.8902 | 7.01 | 5.076 × 10−5 | 0.6937 | 41.2 | 0.00884 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, M.; Yao, K.; Dong, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F.; Luo, R. Effects of Solid Solution Heat Treatment on the Corrosion Behavior of 800H Used in Fourth-Generation Nuclear Power Generators. Materials 2026, 19, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010143

Liu Y, Guo X, Wang M, Yao K, Dong H, Li Y, Wang Z, Wang F, Luo R. Effects of Solid Solution Heat Treatment on the Corrosion Behavior of 800H Used in Fourth-Generation Nuclear Power Generators. Materials. 2026; 19(1):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010143

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yu, Xiaoyuan Guo, Min Wang, Kaixing Yao, Huiqing Dong, Yafan Li, Zhidong Wang, Feng Wang, and Rui Luo. 2026. "Effects of Solid Solution Heat Treatment on the Corrosion Behavior of 800H Used in Fourth-Generation Nuclear Power Generators" Materials 19, no. 1: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010143

APA StyleLiu, Y., Guo, X., Wang, M., Yao, K., Dong, H., Li, Y., Wang, Z., Wang, F., & Luo, R. (2026). Effects of Solid Solution Heat Treatment on the Corrosion Behavior of 800H Used in Fourth-Generation Nuclear Power Generators. Materials, 19(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010143