Porosity/Cement Index and Machine Learning Models for Predicting Tensile and Compressive Strength of Cemented Silt in Varying Compaction Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

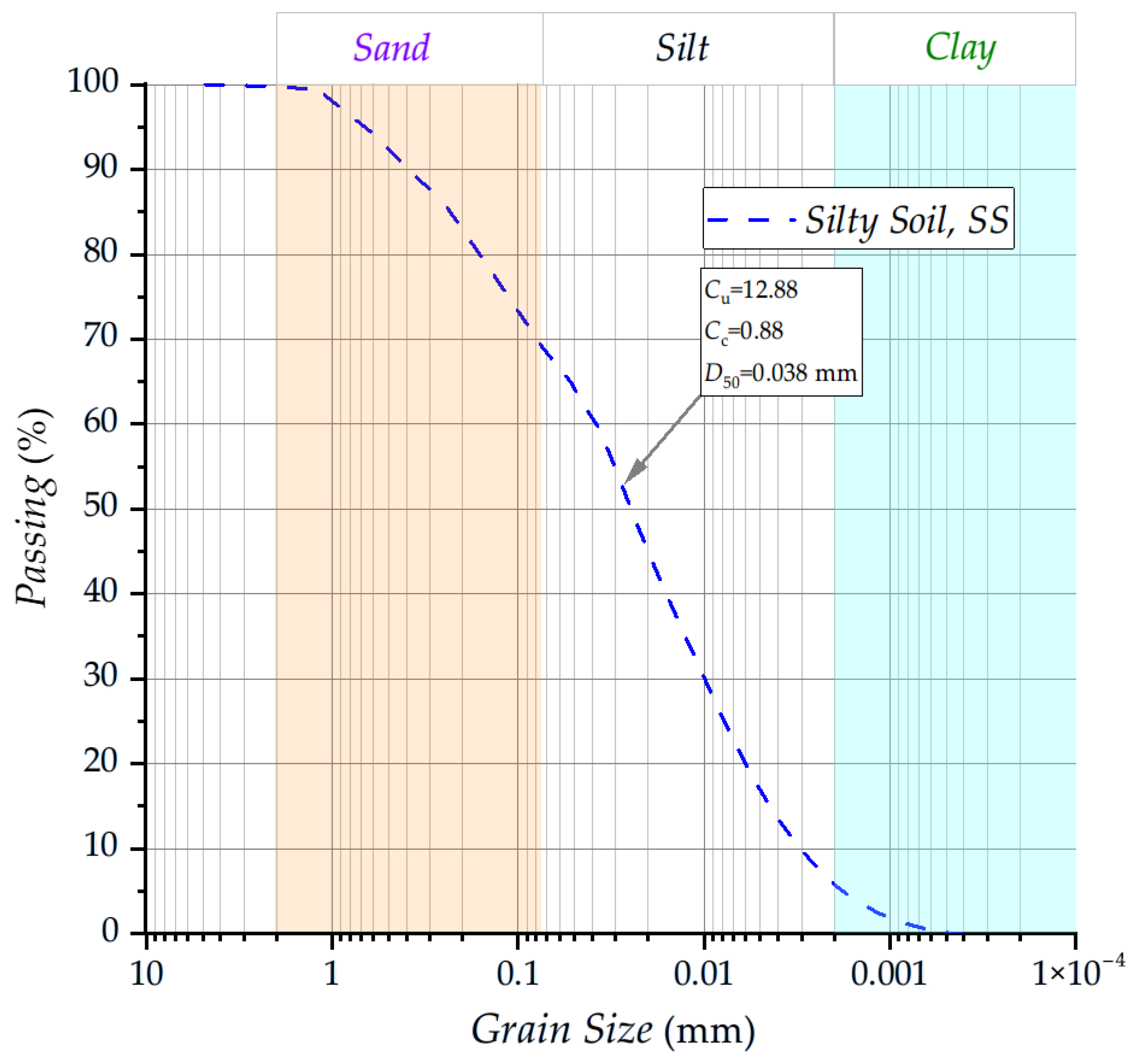

2.1. Materials

2.2. Specimen Molding and Preparation

2.3. Unconfined Compressive and Splitting Tensile Protocols

3. Machine Learning Methodology

4. Results and Discussions

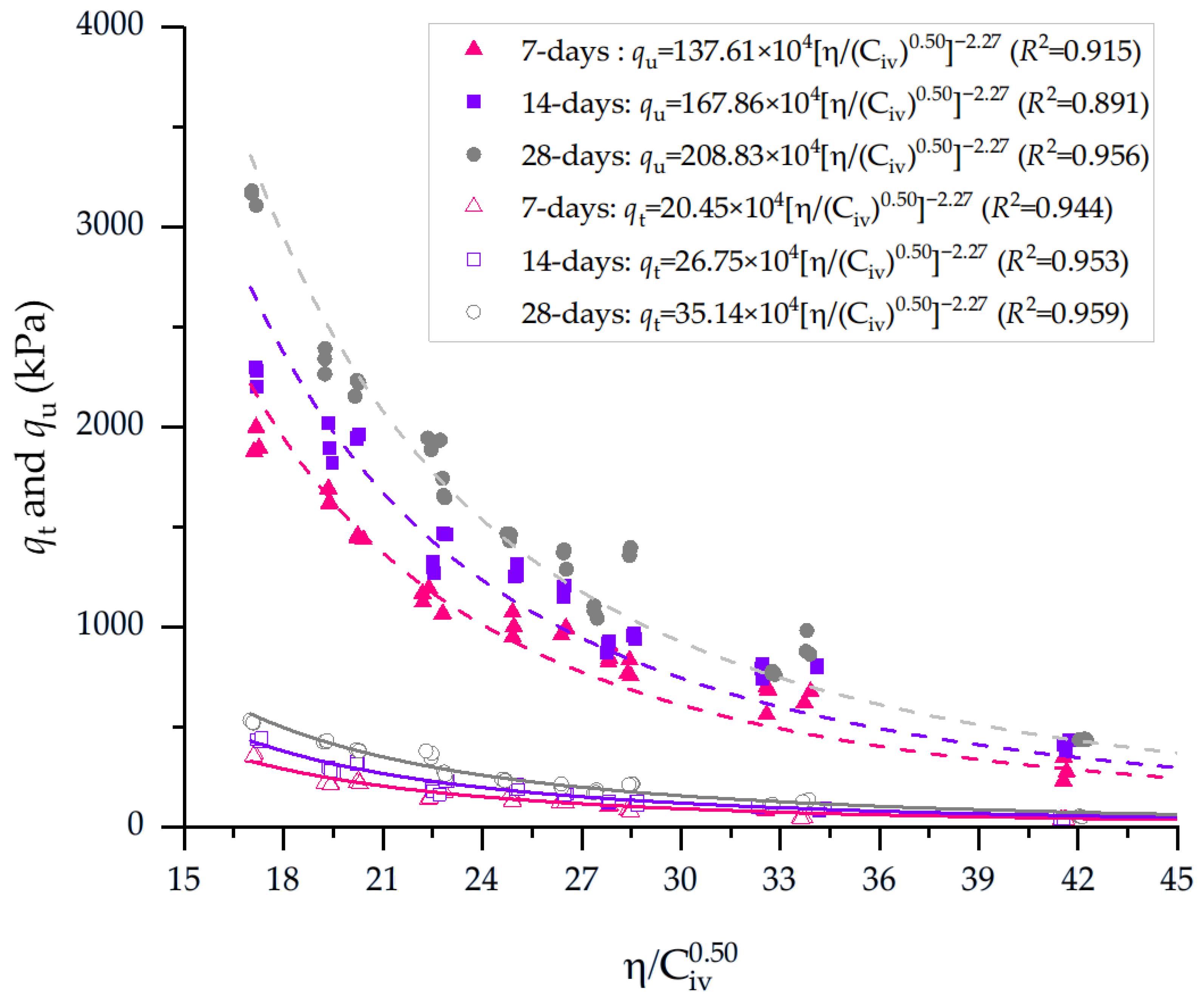

4.1. Effects of Porosity-to-Cement Index on Unconfined Compressive and Splitting Tensile Strength Considering the Optimum Compaction Conditions

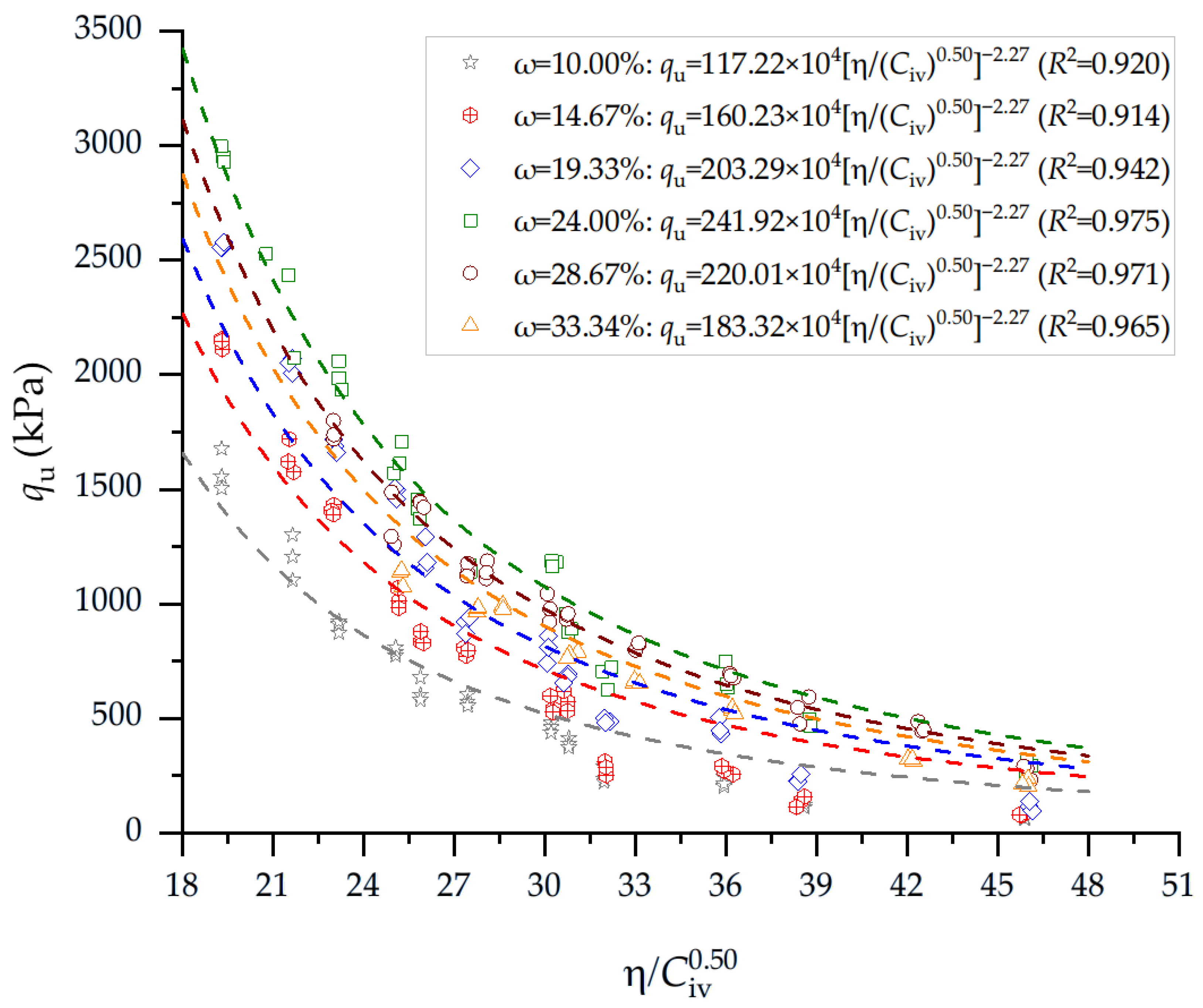

4.2. Effects of Porosity-to-Cement Index on Unconfined Compressive and Splitting Tensile Strength Considering the Non-Optimum Compaction Conditions

4.3. Normalization Equations for Estimating the Unconfined Compressive and Splitting Tensile Strength

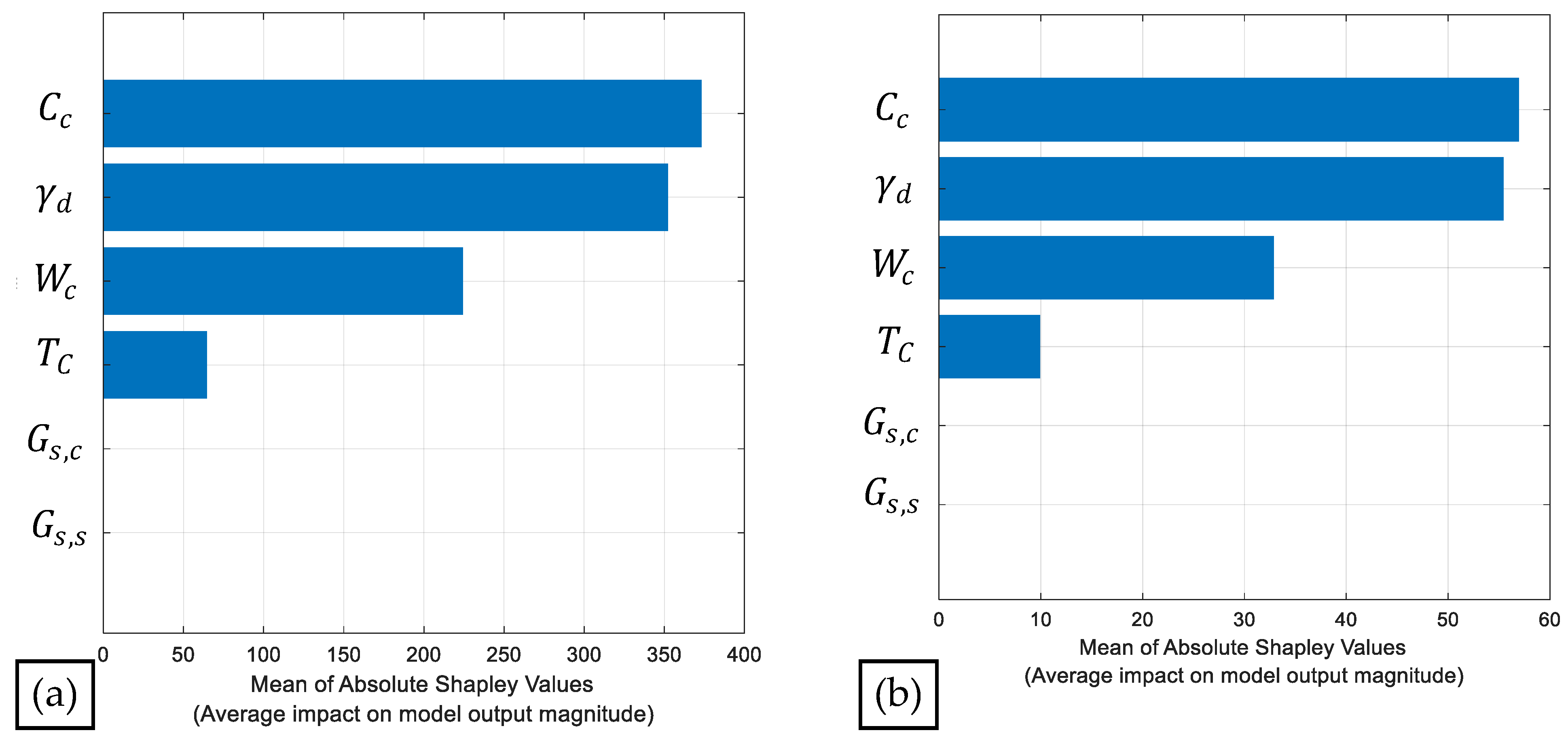

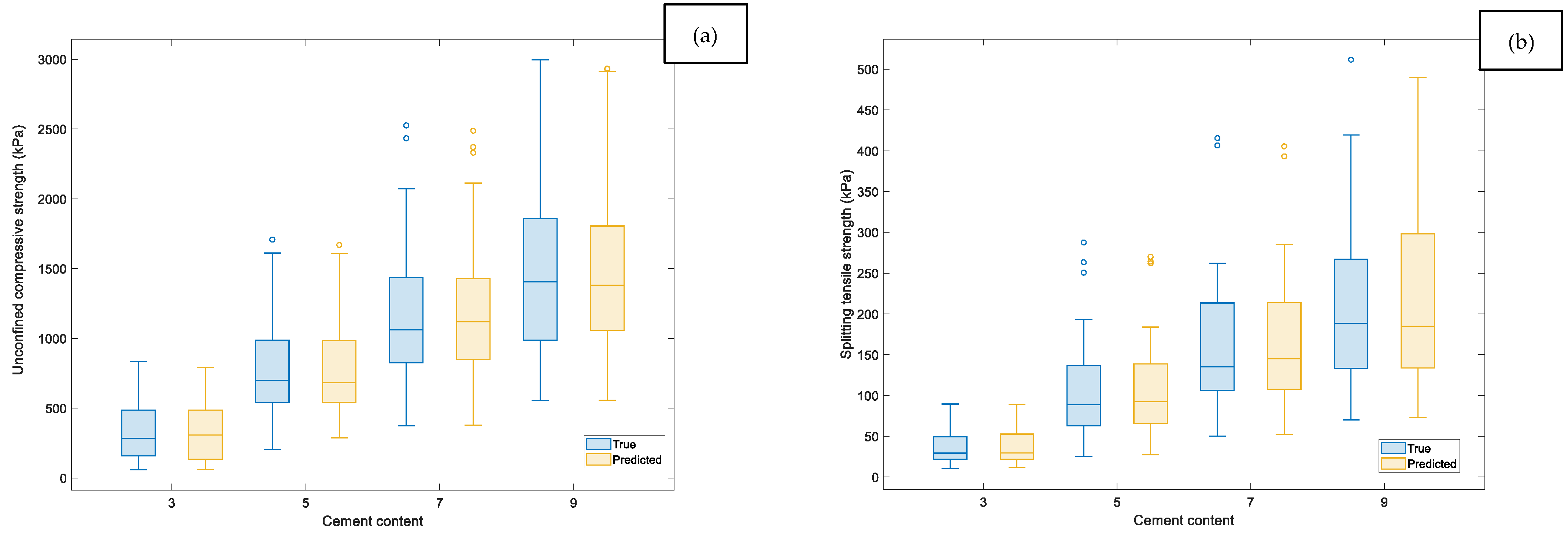

4.4. Machine Learning Results

5. Conclusions

- -

- The porosity–cement index (η/Civ) proved to be a robust and unifying parameter for predicting the mechanical behavior of the cemented silt, exhibiting strong correlations for both and . For 28-day curing, the best-fit exponent converged to x = 0.50, producing high determination coefficients (R2 = 0.98 for and R2 = 0.97 for ), confirming the validity of a power-law relationship for materials compacted under Standard, Intermediate, and Modified energies.

- -

- Mechanical strength increased markedly with decreasing η/Civ, demonstrating the dominant influence of porosity reduction over cement volume fraction. For , mixtures with η/Civ = 45–46 exhibited very low strengths (60–80 kPa), whereas reducing η/Civ to 19–21 yielded between 1500 and 3000 kPa, representing 15–25-fold increases. For , the same trend was observed: at η/Civ = 46, remained below 15 kPa, while values of 22–23 produced between 130 and 330 kPa, and η/Civ = 19 yielded peak strengths above 400 kPa, confirming a consistent strengthening mechanism for both tensile and compressive responses.

- -

- Compaction water content played a critical role in defining the porosity–cement state and the corresponding strength envelope. Specimens molded at w = 10.0–10.2% achieved the lowest porosities (39%) and the highest values, reaching 1500–3000 kPa depending on Civ. In contrast, increasing the water content to 19–24% raised the porosity to 50–51%, resulting in a strength below 120 kPa for the duplicate cement content. This demonstrates the strong coupling between molding water content, packing structure, and cementation efficiency.

- -

- Machine learning models (Gaussian Process Regression, Matern 5/2 kernel) outperformed the empirical porosity–cement model in prediction accuracy, achieving R2 = 0.963 (validation) and R2 = 0.997 (testing) for and R2 = 0.984–0.988 for . The ML models captured nonlinear interactions among moisture, density, curing age, and binder content that are not explicitly represented in the η/Civ formulation. However, when used together, both approaches provide complementary insights: η/Civ explains the mechanics, while ML enhances predictive precision.

- -

- The combined framework of porosity–cement index + machine learning offers a robust dual methodology for the design of cemented silt geomaterials, enabling both mechanistic understanding and high-accuracy prediction. This study demonstrates that η/Civ efficiently generalizes physical behavior across compaction energies and moisture states, while ML provides superior prediction for engineering applications. This integrated approach significantly reduces experimental effort and enables the optimization of mix designs for sustainable ground improvement.

- -

- While ML algorithms provide superior predictive accuracy, η/Civ offers a mechanistic explanation of strength development across varying compaction states. The combined framework demonstrates that physically based indices and data-driven models are complementary rather than redundant, providing a practical and robust methodology for the design and optimization of cement-stabilized soils.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Consoli, N.C.; Foppa, D.; Festugato, L.; Heineck, K.S. Key Parameters for Strength Control of Artificially Cemented Soils. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2007, 133, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larnach, W.J. Relationship between Dry Density, Voids/Cement Ratio and the Strength of Soil-Cement Mixtures. Civ. Eng. Public Work. Rev. UK 1960, 60, 903–905. [Google Scholar]

- Consoli, N.C.; Dalla Rosa, A.; Corte, M.B.; Lopes, L.D.S.; Consoli, B.S. Porosity-Cement Ratio Controlling Strength of Artificially Cemented Clays. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2011, 23, 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuermann Filho, H.C.; Dias Miguel, G.; Cesar Consoli, N. Porosity/Cement Index over a Wide Range of Porosities and Cement Contents. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 06021011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román Martínez, C.; Nuñez de la Rosa, Y.E.; Estrada Luna, D.; Baldovino, J.A.; Jordi Bruschi, G. Strength, Stiffness, and Microstructure of Stabilized Marine Clay-Crushed Limestone Waste Blends: Insight on Characterization through Porosity-to-Cement Index. Materials 2023, 16, 4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, N.C.; da Silva, A.; Barcelos, A.M.; Festugato, L.; Favretto, F. Porosity/Cement Index Controlling Flexural Tensile Strength of Artificially Cemented Soils in Brazil. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2020, 38, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nierwinski, H.P.; Sosnoski, J.; Heidemann, M. Evaluation of Strength and Durability of Compacted Bauxite Tailings Treated with Cement. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 5141–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldovino, J.D.J.A.; Ortega, R.T.; Nuñez de la Rosa, Y.E. Experimental Stabilization of Clay Soils in Cartagena de Indias Colombia: Influence of Porosity/Binder Index. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibeigibeni, A.; Stochino, F.; Zucca, M.; Gayarre, F.L. Enhancing Concrete Sustainability: A Critical Review of the Performance of Recycled Concrete Aggregates (RCAs) in Structural Concrete. Buildings 2025, 15, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, H.N.; Shiva Kumar, G.; Ramaraju, H.K.; Ujwal, M.S.; Vinay, A.; Pandit, P. Machine Learning Framework for Predicting and Improving the Unconfined Compressive Strength and California Bearing Ratio of Lateritic Soil Stabilized with Industrial Wastes. Discov. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daimary, N.; Sarmah, D.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Barman, U.; Saikia, M.J. Geotechnical Performance of Lateritic Soil Subgrades Stabilized with Agro-Industrial Waste: An Experimental Assessment and ANN-Based Predictive Modelling. Geotechnics 2025, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Yao, Q.; Gu, S.; Yang, J. Efficient Prediction of California Bearing Ratio in Solid Waste-Cement-Stabilized Soil Using Improved Hybrid Extreme Gradient Boosting Model. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 43, 111627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafi, M.; Javed, I.; Ekinci, A. Evaluating the Strength, Durability and Porosity Characteristics of Alluvial Clay Stabilized with Marble Dust as a Sustainable Binder. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Y.O.; Villota-Mora, A.J.E.; Brandão, D.L.; Orioli, M.A.; Britto, T.S.S.; Baldovino, J.A.; dos Santos Izzo, R.L. Enhancing Soil–Cement Properties Using Glass Polishing Waste: Impact of Porosity and Binder Indices. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2025, 43, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, I.S.; Fagundes, D.D.F.; Nierwinski, H.P. Effects of Ettringite Formation on the Stability of Cement-Treated Sediments. Resources 2025, 14, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.B.; Iravanian, A.; Selman, M.H.; Ekinci, A. Using Waste PET Shreds for Soil Stabilization: Efficiency and Durability Assessment. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2023, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, I.; Ghani, S. Nano-Silica and Machine Learning-Based Soil Stabilization: Advancing Sustainable and Clean Technologies for Resilient Infrastructure. Prog. Eng. Sci. 2025, 2, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sinha, S.; Pradhananga, R. Assessment of Unconfined Compressive Strength of Nano-Doped Fly Ash-Treated Clayey Soil Using Machine Learning Tools. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, G.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wu, J. A Physics-Informed and SHAP-Enhanced Modeling Framework for Predicting Strength of Cement-Stabilized Soil. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, I.; Ghani, S.; Paramasivam, P.; Tufa, M.A. Development of an Optimized Deep Learning Model for Predicting Slope Stability in Nano Silica Stabilized Soils. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Tu, Y.; Yang, J. Indirect Estimation of Compressive Strength of Industrial Byproduct-Geopolymer Stabilized Cohesive Soils: A Novel Hybrid Extreme Gradient Boosting Model. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Xue, X.; Xiong, C.; Huang, R.; Du, J.; Li, J.; Liu, K. Data-Driven Prediction of Unconfined Compressive Strength in Stabilized Soils Using Machine Learning. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Automated Machine Learning Techniques for Estimating the Unconfined Compressive Strength of Soil Stabilization. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. (IJIDeM) 2025, 19, 6347–6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Li, Z.; Qin, X.; Dong, S.; Zhao, T.; Li, H. Machine Learning-Based Optimization of Geopolymer-Stabilized Soil Formulation Using Blast Furnace Slag and Fly Ash. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 48, 113500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoru, I.-B.; Owusu-Yeboah, Z.; Aniculăesi, M.; Dascălu, A.V.; Hörtkorn, F.; Amelio, A.; Lungu, I. Prediction of Unconfined Compressive Strength in Cement-Treated Soils: A Machine Learning Approach. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linganagoudar, C.M.; Kumar, G.S.; Ujwal, M.S.; Rohith, G.; Vinay, A.; Pandit, P. Modeling the Unconfined Compressive Strength of Lateritic Soil Treated with FGD Gypsum as a Partial Cement Replacement. Mater. Res. Express 2025, 12, 065501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Y.M.H.; Wudil, Y.S.; Zami, M.S.; Al-Osta, M.A. Machine Learning Approach for Assessment of Compressive Strength of Soil for Use as Construction Materials. Eng 2025, 6, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldovino, J.D.J.A.; Izzo, R.L.D.S.; Pereira, M.D.; Rocha, E.V.D.G.; Rose, J.L.; Bordignon, V.R. Equations Controlling Tensile and Compressive Strength Ratio of Sedimentary Soil–Cement Mixtures under Optimal Compaction Conditions. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 04019320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldovino, J.D.J.A.; Izzo, R.L.D.S.; Feltrim, F.; da Silva, É.R. Experimental Study on Guabirotuba’s Soil Stabilization Using Extreme Molding Conditions. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2020, 38, 2591–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D4318-10; Stardard Test Methods for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit and Plasticity Index of Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010.

- ASTM D854; Standard Test Methods for Specific Gravity of Soil Solids by Water Pycnometer. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- ABNT NBR 6502; Rochas e Solos. Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas: São Paulo, Brazil, 1995.

- ASTM D3080-11; Standard Test Method for Direct Shear Test of Soils under Consolidated Drained Conditions. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2011.

- ABNT NBR 16605-17; Cimento Portland e Outros Materiais Em Pó—Determinação Da Massa Específica. ABNT: São Paulo, Brazil, 2017.

- ASTM D 2166-03; Standard Test Method for Unconfined Compressive Strength of Cohesive Soil 1. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2003.

- ABNT NBR 7222; Informação e Documentação—Artigo em Publicação Periódica Científica Impressa—Apresentação. ABNT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2011.

- Mathworks Statistics and Machine Learning ToolboxTM User’s Guide R2020a; MATLAB Mathworks Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2020.

| Molding γd (kN/m3) | Soil (%) | C (%) | Molding w (%) | tc (Days) | Specimens | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13.0 | 100 | 3 | 10, 14.67, 19.33, 24, 28.67, and 33.34 | 28 | 36 | |

| 100 | 5 | 10, 14.67, 19.33, 24, 28.67, and 33.34 | 28 | 36 | ||

| 100 | 7 | 10, 14.67, 19.33, 24, 28.67, and 33.34 | 28 | 36 | ||

| 100 | 9 | 10, 14.67, 19.33, 24, 28.67, and 33.34 | 28 | 36 | ||

| 13.75 | 100 | 3 | 28.67 and 33.34 | 28 | 12 | |

| 100 | 5 | 28.67 and 33.34 | 28 | 12 | ||

| 100 | 7 | 28.67 and 33.34 | 28 | 12 | ||

| 100 | 9 | 28.67 and 33.34 | 28 | 12 | ||

| 14.5 | 100 | 3 | 10, 14.67, 19.33, 24, and 28.67 | 28 | 30 | |

| 100 | 5 | 10, 14.67, 19.33, 24, and 28.67 | 28 | 30 | ||

| 100 | 7 | 10, 14.67, 19.33, 24, and 28.67 | 28 | 30 | ||

| 100 | 9 | 10, 14.67, 19.33, 24, and 28.67 | 28 | 30 | ||

| 16.0 | 100 | 3 | 10, 14.67, 19.33, and 24 | 28 | 24 | |

| 100 | 5 | 10, 14.67, 19.33, and 24 | 28 | 24 | ||

| 100 | 7 | 10, 14.67, 19.33, and 24 | 28 | 24 | ||

| 100 | 9 | 10, 14.67, 19.33, and 24 | 28 | 24 |

| Energy | Soil (%) | C (%) | OWC (%) | MDD (kN/m3) | tc (Days) | Specimens | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | 100 | 3 | 26 | 13.85 | 7, 14, and 28 | 18 | |

| 100 | 5 | 26.5 | 13.80 | 7, 14, and 28 | 18 | ||

| 100 | 7 | 26 | 14 | 7, 14, and 28 | 18 | ||

| 100 | 9 | 25.5 | 14 | 7, 14, and 28 | 18 | ||

| Intermediate | 100 | 3 | 18 | 15.65 | 7, 14, and 28 | 18 | |

| 100 | 5 | 18 | 15.55 | 7, 14, and 28 | 18 | ||

| 100 | 7 | 18.5 | 15.55 | 7, 14, and 28 | 18 | ||

| 100 | 9 | 18 | 15.55 | 7, 14, and 28 | 18 | ||

| Modified | 100 | 3 | 15 | 16.85 | 7, 14, and 28 | 18 | |

| 100 | 5 | 15 | 17.05 | 7, 14, and 28 | 18 | ||

| 100 | 7 | 14.5 | 16.95 | 7, 14, and 28 | 18 | ||

| 100 | 9 | 15 | 16.95 | 7, 14, and 28 | 18 |

| Model Type (Presets) | Interpretability | |

|---|---|---|

| Easy | Hard | |

| Linear (Linear, Interactions, Robust, and Stepwise) | ||

| Decision Trees (Fine, Medium, and Coarse) | ||

| Support Vector Machine—SVM (Linear, Quadratic, Cubic, Fine Gaussian, Medium Coarse, and Coarse Gaussian) | (linear SVM) | (other kernels) |

| Efficiently Trained Linear (Least Squares and Linear SVM) | ||

| Gaussian Process Regression (Squared Exponential, Matern 5/2, Exponential, and Rational Quadratic) | ||

| Kernel models (SVM and Least Squares) | ||

| Ensembles of Trees (Boosted and Bagged) | ||

| Neural Networks (Narrow, Medium, Wide, Bilayered, and Trilayered) | ||

| Model Type | Formula | Equation No. | Observation | Notation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | (2) | = response, = predictor, = intersection term, = slope term, and = error term. | ||

| Trees | Not presented | - | Prediction begins at the root node and proceeds down to a leaf node. | None. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | (3) | It is used for nonlinear SVM regression. | = kernel function, = function for computing new values, = observations, and = bias term. | |

| Efficiently Trained Linear | Not presented | - | Corresponds to linear least squares models and linear SVM. | None. |

| Gaussian Process Regression | (4) | None. | = coefficient that depends on data, = response, = predictors, = Gaussian distribution, = variance, and = vector of basis functions. | |

| Kernel Models | (5) | None. | = function for computing new values, = kernel function, and = coefficients. | |

| Ensembles of Trees | (6) | Applicable for the boosting algorithm. | = function for computing new values, = weights of the weak hypothesis, and ) = prediction of learner with index . | |

| Neural Networks | (7) | It corresponds to the trilayered neural network. | = output vector, = input vector, = refers to weight, = input matrix, and = layer matrix. The numbers refer to the layers. |

| Variables | Identification | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Predictors (inputs obtained from experimental program) | = water content. = unit dry weight. = cement content. = specific gravity content. = specific gravity of soil. = curing time. | Experimental Program (Section 2). |

| Responses (outputs computed by ML models) | = unconfined compressive strength. = splitting tensile strength. | Machine learning models (Section 3). |

| Test | Curing Time | A Value (×104) | x Exponent | B Exponent | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 137.61 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.915 | |

| 14 | 167.86 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.891 | |

| 28 | 208.83 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.956 | |

| 7 | 20.45 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.944 | |

| 14 | 26.75 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.953 | |

| 28 | 35.14 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.959 |

| Test | Water Content | A Value (×104) | x Exponent | B Exponent | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.00 | 117.22 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.920 | |

| 14.67 | 160.23 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.914 | |

| 19.33 | 203.29 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.942 | |

| 24.00 | 241.92 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.975 | |

| 28.67 | 220.01 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.971 | |

| 33.34 | 183.32 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.965 | |

| 10.00 | 17.19 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.905 | |

| 14.67 | 21.44 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.863 | |

| 19.33 | 27.51 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.893 | |

| 24.00 | 38.72 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.920 | |

| 28.67 | 34.63 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.933 | |

| 33.34 | 25.41 | 0.50 | −2.27 | 0.914 |

| Preset | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (V) | R2 (V) | RMSE (T) | R2 (T) | RMSE (V) | R2 (V) | RMSE (T) | R2 (T) | |

| Linear | 305.1 | 0.103 | 242.2 | −0.462 | 43.2 | 0.803 | 56.2 | 0.765 |

| Interactions Linear | 258.3 | 0.357 | 223.3 | −0.242 | 26.1 | 0.928 | 33.9 | 0.914 |

| Robust Linear | 326.4 | −0.026 | 201.0 | −0.007 | 46.6 | 0.772 | 63.6 | 0.698 |

| Stepwise Linear | 256.2 | 0.368 | 226.6 | −0.279 | 26.7 | 0.925 | 33.7 | 0.915 |

| Fine Tree | 154.1 | 0.771 | 60.5 | 0.909 | 41.7 | 0.817 | 38.7 | 0.889 |

| Medium Tree | 221.5 | 0.527 | 138.6 | 0.522 | 51.6 | 0.719 | 57.1 | 0.757 |

| Coarse Tree | 295.3 | 0.160 | 200.6 | −0.002 | 68.0 | 0.513 | 82.0 | 0.499 |

| Linear SVM | 321.9 | 0.002 | 206.8 | −0.066 | 45.1 | 0.786 | 60.8 | 0.725 |

| Quadratic SVM | 223.3 | 0.520 | 190.4 | 0.096 | 23.7 | 0.941 | 30.7 | 0.930 |

| Cubic SVM | 213.0 | 0.563 | 118.3 | 0.651 | 98.3 | −0.016 | 61.3 | 0.721 |

| Fine Gaussian SVM | 265.5 | 0.321 | 145.2 | 0.475 | 33.9 | 0.879 | 46.5 | 0.839 |

| Medium Gaussian SVM | 277.7 | 0.257 | 175.3 | 0.234 | 23.7 | 0.941 | 26.5 | 0.948 |

| Coarse Gaussian SVM | 320.5 | 0.010 | 205.8 | −0.055 | 51.0 | 0.726 | 66.7 | 0.669 |

| Efficient Linear Least Squares | 304.9 | 0.104 | 240.3 | −0.439 | 48.1 | 0.756 | 61.1 | 0.722 |

| Efficient Linear SVM | 320.3 | 0.012 | 205.3 | −0.050 | 73.5 | 0.431 | 88.7 | 0.414 |

| Boosted Trees | 109.9 | 0.884 | 51.0 | 0.935 | 26.8 | 0.925 | 33.9 | 0.914 |

| Bagged Trees | 177.6 | 0.696 | 105.6 | 0.722 | 38.6 | 0.843 | 48.0 | 0.828 |

| Squared Exponential GPR | 58.0 | 0.968 | 11.2 | 0.997 | 13.9 | 0.980 | 12.8 | 0.988 |

| Matern 5/2 GPR | 61.8 | 0.963 | 10.5 | 0.997 | 12.2 | 0.984 | 12.6 | 0.988 |

| Exponential GPR | 55.7 | 0.970 | 12.8 | 0.996 | 13.9 | 0.980 | 10.9 | 0.991 |

| Rational Quadratic GPR | 61.7 | 0.963 | 10.3 | 0.997 | 12.3 | 0.984 | 12.4 | 0.989 |

| Narrow NN | 154.3 | 0.771 | 118.4 | 0.651 | 21.9 | 0.949 | 25.3 | 0.952 |

| Medium NN | 60.1 | 0.965 | 25.2 | 0.984 | 15.3 | 0.975 | 14.6 | 0.984 |

| Wide NN | 35.4 | 0.988 | 15.0 | 0.994 | 14.6 | 0.978 | 11.9 | 0.990 |

| Bilayered NN | 106.0 | 0.892 | 97.2 | 0.765 | 19.0 | 0.962 | 13.8 | 0.986 |

| Trilayered NN | 73.0 | 0.949 | 25.4 | 0.984 | 17.2 | 0.969 | 14.4 | 0.984 |

| SVM Kernel | 321.6 | 0.004 | 204.6 | −0.043 | 92.4 | 0.101 | 120.2 | −0.076 |

| Least Squares Regression Kernel | 166.2 | 0.734 | 82.9 | 0.829 | 32.8 | 0.887 | 63.6 | 0.699 |

| Response | Porosity-to-Cement Model | Matern 5/2 GPR Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equation | R2 | R2 | ||

| Validation | Testing | |||

| Equation (9) | 0.951 | 0.963 | 0.997 | |

| Equation (10) | 0.957 | 0.984 | 0.988 | |

| Equation (11) | 0.853 | 0.963 | 0.997 | |

| Equation (12) | 0.738 | 0.984 | 0.988 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Baldovino, J.A.; Coronado-Hernández, O.E.; Nuñez de la Rosa, Y.E. Porosity/Cement Index and Machine Learning Models for Predicting Tensile and Compressive Strength of Cemented Silt in Varying Compaction Conditions. Materials 2026, 19, 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030498

Baldovino JA, Coronado-Hernández OE, Nuñez de la Rosa YE. Porosity/Cement Index and Machine Learning Models for Predicting Tensile and Compressive Strength of Cemented Silt in Varying Compaction Conditions. Materials. 2026; 19(3):498. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030498

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaldovino, Jair Arrieta, Oscar E. Coronado-Hernández, and Yamid E. Nuñez de la Rosa. 2026. "Porosity/Cement Index and Machine Learning Models for Predicting Tensile and Compressive Strength of Cemented Silt in Varying Compaction Conditions" Materials 19, no. 3: 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030498

APA StyleBaldovino, J. A., Coronado-Hernández, O. E., & Nuñez de la Rosa, Y. E. (2026). Porosity/Cement Index and Machine Learning Models for Predicting Tensile and Compressive Strength of Cemented Silt in Varying Compaction Conditions. Materials, 19(3), 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030498