Assessment of the Possibilities of Developing Effective Building Thermal Insulation Materials from Corrugated Textile Sheets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

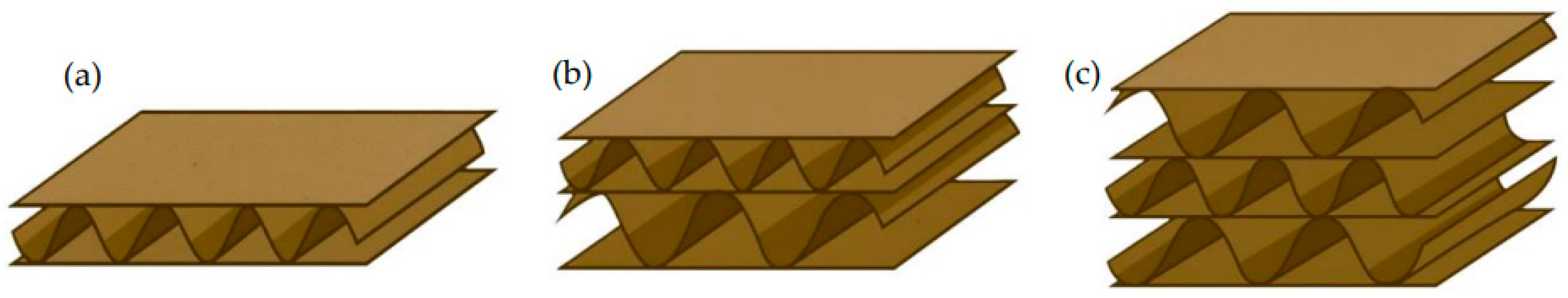

2.2. Preparation of Corrugated Sheets and Thermal Insulation Materials

2.3. Test Methods

2.4. Research Process Flowchart

3. Results

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buska, A.; Mačiulaitis, R.; Rudžionis, Ž. Mineral Wool Macrostructure Parameter’s Relation with Product’s Mechanical Properties. Mater. Sci.-Medz. 2016, 22, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, T. Verification of Density Predicted for Prevention of Settling of Loose-fill Cellulose Insulation in Walls. J. Build. Phys. 2003, 27, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerkez, I.; Kocer, H.; Broughton, R. A Practical Cost Model for Selecting Nonwoven Insulation Materials. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2012, 7, 155892501200700101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayyani, I.; Shaw, A.D.; Saavedra Flores, E.I.; Friswell, M.I. The mechanics of composite corrugated structures: A review with applications in morphing aircraft. Compos. Struct. 2015, 133, 358–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.S.; Guoxing, L.G. Thin-walled corrugated structures: A review of crashworthiness designs and energy absorption characteristics. Thin-Walled Struct. 2020, 157, 106995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiloul, A.; Blanchet, P.; Boudaud, C. Mechanical characterization of corrugated wood-based panels and potential structural applications in a building. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 391, 131896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Song, R.; He, B.; Meng, S.; Zhou, X. Mechanical properties and damage mechanism of corrugated steel plate–concrete composite structures as primary supports of tunnels. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemahvazi, S.; Tanner, D.; Zenkert, D. Corrugated all-composite sandwich structures. Part 2: Failure mechanisms and experimental programme. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 920–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, Z. Rigidity of corrugated plate sidewalls and its effect on the modular structural design. Eng. Struct. 2018, 175, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaca, F.I.; Cananau, S.; Calin, A.; Bucur, M.; Prisecaru, D.A.; Stoica, M. Mechanical Analysis of Corrugated Cardboard Subjected to Shear Stresses. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, L.J. Research on Corrugated Cardboard and Its Application. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 535–537, 2171–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadiji, T.; Berry, T.M.; Coetzee, C.J.; Opara, L.U. Investigating the Mechanical Properties of Paperboard Packaging Material for Handling Fresh Produce Under Different Environmental Conditions: Experimental Analysis and Finite Element Modelling. J. Appl. Packag. Res. 2017, 9, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist, A.C.; Suhling, J.C.; Urbanik, T.J. Nonlinear finite element modeling of corrugated board. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mechanics of Cellulosic Materials, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 27–30 June 1999; pp. 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Asdrubali, F.; Pisello, A.L.; Alessandro, F.D.; Bianchi, F.; Cornicchia, M.; Fabiani, C. Innovative Cardboard Based Panels with Recycled Materials from the Packaging Industry: Thermal and Acoustic Performance Analysis. Energy Procedia 2015, 78, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cekon, M.; Struhala, K.; Slávik, R. Cardboard-Based Packaging Materials as Renewable Thermal Insulation of Buildings: Thermal and Life-Cycle Performance. J. Renew. Mater. 2017, 5, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray-Stuart, E.M.; Bronlund, J.E.; Navaranjan, N.; Redding, G.P. Measurement of thermal conductivity of paper and corrugated fibreboard with prediction of thermal performance for design applications. Cellulose 2019, 26, 5695–5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, J.W.; Lee, J.H.; Hong, S.I. Water resistance and mechanical properties of biopolymer (alginate and soy protein) coated paperboards. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 39, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaoui, S.; Aboura, Z.; Benzeggagh, M.L. Effects of the environmental conditions on the mechanical behaviour of the corrugated cardboard. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokozeki, T.; Takeda, S.; Ogasawara, T.; Ishikawa, T. Mechanical properties of corrugated composites for candidate materials of flexible wing structures. Compos.-A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2006, 37, 1578–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierksma, G.; Wanders, H.L.T. The manufacturing of heavy weight cardboard. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2000, 65, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.K.; Agrawal, A.; Chaudhary, R.; Chauhan, A.; Sharma, P.; Yadav, A. Automatic corrugated box making line. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 79, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogalka, M.; Grabski, J.K.; Garbowski, T. Identification of Geometric Features of the Corrugated Board Using Images and Genetic Algorithm. Sensors 2023, 23, 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielecki, M.; Chmielewska-Wurch, A.; Damiecki, T.; Patalan, B.; Sloma, M.; Zdzieblo, S. General issues and the recommended standards for corrugated board and corrugated board packaging. In Information Paper; The Association of Polish Papermakers: Łódź, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Weissmüller, J.; Duan, H.L. Mechanics of corrugated surfaces. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2010, 58, 1552–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. Energy absorption diagrams of multi-layer corrugated boards. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.-Mat. Sci. 2010, 25, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogalka, M.; Grabski, J.K.; Garbowski, T. Deciphering Double-Walled Corrugated Board Geometry Using Image Analysis and Genetic Algorithms. Sensors 2024, 24, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szewczyk, W.; Bieńkowska, M. Effect of corrugated board structure. Wood Res. 2020, 65, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrówczyński, D.; Knitter-Piątkowska, A.; Garbowski, T. Optimal Design of Double-Walled Corrugated Board Packaging. Materials 2022, 15, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.C.; Clure, J.L. Metal-Wool Heat Shields for Space Shuttle; Prepared Under Contract No. NAS1-12427; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1974; 61p.

- Birur, G.C.; Siebes, G.; Swanson, T.D. Spacecraft Thermal Control. In Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology, 3rd ed.; Meyers, R.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consolo, R.C.; Boetcher, S.K.S. Chapter One—Advances in spacecraft thermal control. In Advances in Heat Transfer; Abraham, J.P., Gorman, J.M., Minkowycz, W.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 56, pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.S. Multilayer Insulation for Spacecraft Applications. In COSPAR Colloquia Series; Hsiao, F.B., Ed.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1999; Volume 10, pp. 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachikawa, S.; Nagano, H.; Ohnishi, A.; Nagasaka, Y. Advanced Passive Thermal Control Materials and Devices for Spacecraft: A Review. Int. J. Thermophys. 2022, 43, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 204:2016; Classification of Thermoplastic Wood Adhesives for Non-Structural Applications. European Standard: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- EN ISO 29470:2020; Thermal Insulating Products for Building Applications—Determination of the Apparent Density. European Standard: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- EN 12667:2001; Thermal Performance of Building Materials and Products—Determination of Thermal Resistance by Means of Guarded Hot Plate and Heat Flow Meter Methods—Products of High and Medium Thermal Resistance. European Standard: Brussels, Belgium, 2001.

- EN ISO 29469:2022; Thermal Insulating Products for Building Applications—Determination of Compression Behaviour. European Standard: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- EN 12089:2013; Thermal Insulating Products for Building Applications—Determination of Bending Behaviour. European Standard: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- Aliu, S.; Amoo, O.M.; Alao, F.I.; Ajadi, S.O. 2—Mechanisms of heat transfer and boundary layers. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy, Applications of Heat, Mass and Fluid Boundary Layers; Fagbenle, R.O., Amoo, O.M., Aliu, S., Falana, A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 23–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, L.D.H.; Pásztory, Z. An overview of factors influencing thermal conductivity of building insulation materials. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimkienė, A.; Vėjelis, S.; Vaitkus, S. Analysis and Use of Wood Waste in Lithuania for the Development of Engineered Wood Composite. Forests 2025, 16, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.M.D.; Desole, M.P.; Gisario, A.; Barletta, M. Evaluation of wave configurations in corrugated boards by experimental analysis (EA) and finite element modeling (FEM): The role of the micro-wave in packaging design. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 4963–4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glittenberg, D. Starch Based Biopolymers in Paper, Corrugating and Other Industrial Applications. In Polymer Science A. Comprehensive Reference; Matyjaszewski, K., Moller, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 165–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peças, P.; Carvalho, H.; Salman, H.; Leite, M. Natural Fibre Composites and Their Applications: A Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2018, 2, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, Y.; Ballupete Nagaraju, S.; Puttegowda, M.; Verma, A.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S. Biopolymer-Based Composites: An Eco-Friendly Alternative from Agricultural Waste Biomass. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manickaraj, K.; Thirumalaisamy, R.; Palanisamy, S.; Ayrilmis, N.; Massoud, E.E.S.; Palaniappan, M.; Sankar, S.L. Value-added utilization of agricultural wastes in biocomposite production: Characteristics and applications. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2025, 1549, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vėjelis, S.; Vaitkus, S.; Skulskis, V.; Kremensas, A.; Kairytė, A. Performance Evaluation of Thermal Insulation Materials from Sheep’s Wool and Hemp Fibres. Materials 2024, 17, 3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savio, L.; Pennacchio, R.; Patrucco, A.; Manni, V.; Bosia, D. Natural Fibre Insulation Materials: Use of Textile and Agri-food Waste in a Circular Economy Perspective. Mater. Circ. Econ. 2022, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulutaş, A.; Balo, F.; Topal, A. Identifying the Most Efficient Natural Fibre for Common Commercial Building Insulation Materials with an Integrated PSI, MEREC, LOPCOW and MCRAT Model. Polymers 2023, 15, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosentino, L.; Fernandes, J.; Mateus, R.A. Review of Natural Bio-Based Insulation Materials. Energies 2023, 16, 4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, V.; Nakano, Y.; Tanaka, F.; Hamanaka, D.; Uchino, T. Preserving the strength of corrugated cardboard under high humidity conditions using nano-sized mists. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2010, 70, 2123–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müssig, J.; Komeno, M. Development of a Predictive Model for the Thermal Conductivity of Natural Fiber Insulation: A Novel Approach for Quality Control. J. Nat. Fibers 2024, 21, 2371909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekavicius, V.; Shipkovs, P.; Ivanovs, S.; Rucins, A. Thermo-Insulation Properties of Hemp-Based Products. Latv. J. Phys. Tech. Sci. 2015, 52, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kymäläinen, H.-R.; Sjöberg, A.-M. Flax and hemp fibres as raw materials for thermal insulations. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Profile | Take-Up Ratio | Height, mm | Pitch, mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| O | 1.14 | 0.3 | 1.2 |

| N | 1.11–1.8 | 0.4–0.5 | 1.8 |

| G | 1.17 | 0.5 | 1.8 |

| F | 1.19–1.28 | 0.7–0.8 | 2.4–2.5 |

| E | 1.20–1.35 | 1.1–1.4 | 3.2–3.7 |

| B | 1.26–1.48 | 2.3–2.8 | 6.1–6.6 |

| C | 1.36–1.56 | 3.4–4.0 | 7.4–8.3 |

| A | 1.37–1.53 | 4.1–4.7 | 8.7–9.5 |

| K | 1.50 | 5.94 | 11.7 |

| D | 1.48 | 7.38 | 15.0 |

| Type of Fibre | Length of Fibres, mm | Fibre Diameter, µm | Linear Density, dtex | Melting Point, °C | Colour | Producer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemp fibres | 40–60 | 17–22 | - | - | light brown | JSC Natūralus Pluoštas, Kėdainiai, Lithuania |

| Polylactide | 51 | 16–19 | 4.4 | 130 | white | Max Model S.A.S, Lyon, France |

| Glue Type | Colour | Moisture Resistance Class [34] | Open Holding Time, min | Compression Time, min | Viscosity, mPas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Universal | White | D3 | 5–15 | 20–40 | 11,000 |

| Group of Specimens | Form of Specimen | Number of Layers, pcs | Wave Height, mm | Thickness, mm | Density, kg/m3 | Thermal Conductivity, W/(m·K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coarse wave sheets | 8 | 7.13 ± 0.83 | 54.2 ± 0.31 | 34.5 ± 1.40 | 0.0459 ± 0.00061 |

| 2 | Medium wave sheets | 11 | 5.08 ± 0.47 | 53.3 ± 0.57 | 42.3 ± 1.86 | 0.0386 ± 0.00046 |

| 3 | Fine wave sheets | 18 | 3.02 ± 0.68 | 53.5 ± 0.76 | 48.6 ± 2.97 | 0.0326 ± 0.00074 |

| 4 | Coarse wave sheets (glued) | 8 | 7 | 54.3 ± 0.50 | 51.9 ± 0.62 | 0.0535 ± 0.00025 |

| 5 | Medium wave sheets (glued) | 11 | 5 | 51.0 ± 0.47 | 64.3 ± 0.70 | 0.0470 ± 0.00035 |

| 6 | Fine wave sheets (glued) | 18 | 3 | 52.3 ± 0.90 | 76.8 ± 1.19 | 0.0385 ± 0.00040 |

| 7 | Non-corrugated mat | 11 | 0 | 53.1 ± 0.36 | 34.5 ± 0.25 | 0.0396 ± 0.00027 |

| 8 | Non-corrugated mat | 14 | 0 | 55.2 ± 0.60 | 42.3 ± 0.06 | 0.0392 ± 0.00032 |

| 9 | Non-corrugated mat | 16 | 0 | 53.5 ± 0.36 | 48.6 ± 0.47 | 0.0381 ± 0.00071 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vėjelis, S.; Drozd, A.; Skulskis, V.; Vaitkus, S. Assessment of the Possibilities of Developing Effective Building Thermal Insulation Materials from Corrugated Textile Sheets. Materials 2026, 19, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010188

Vėjelis S, Drozd A, Skulskis V, Vaitkus S. Assessment of the Possibilities of Developing Effective Building Thermal Insulation Materials from Corrugated Textile Sheets. Materials. 2026; 19(1):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010188

Chicago/Turabian StyleVėjelis, Sigitas, Aliona Drozd, Virgilijus Skulskis, and Saulius Vaitkus. 2026. "Assessment of the Possibilities of Developing Effective Building Thermal Insulation Materials from Corrugated Textile Sheets" Materials 19, no. 1: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010188

APA StyleVėjelis, S., Drozd, A., Skulskis, V., & Vaitkus, S. (2026). Assessment of the Possibilities of Developing Effective Building Thermal Insulation Materials from Corrugated Textile Sheets. Materials, 19(1), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010188