Investigation of Ensemble Machine Learning Models for Estimating the Ultimate Strain of FRP-Confined Concrete Columns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Prediction Models

2.1. Empirical Models for Predicting the Ultimate Strain of FRP-Confined Concrete

2.1.1. Mechanism Confinement of FRP-Confined Concrete

2.1.2. Empirical Models for Ultimate Strain of FRP-Confined Concrete

2.2. Machine Learning Models

2.2.1. Linear Regression (LR)

2.2.2. Gaussian Process (GP)

2.2.3. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

2.2.4. Support Vector Regression (SVR)

2.2.5. k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN)

2.2.6. -Star

2.2.7. Decision Tree

2.2.8. M5 Tree

2.2.9. M5Rules Models

2.2.10. Decision Table

2.2.11. Ensemble Models

2.2.12. Model Construction and Ten-Fold Cross-Validation Technique

3. Test Database

3.1. Data Collections

3.2. Pearson’s Correlation Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Statistical Indicators

4.2. The Estimation Accuracy of the Models

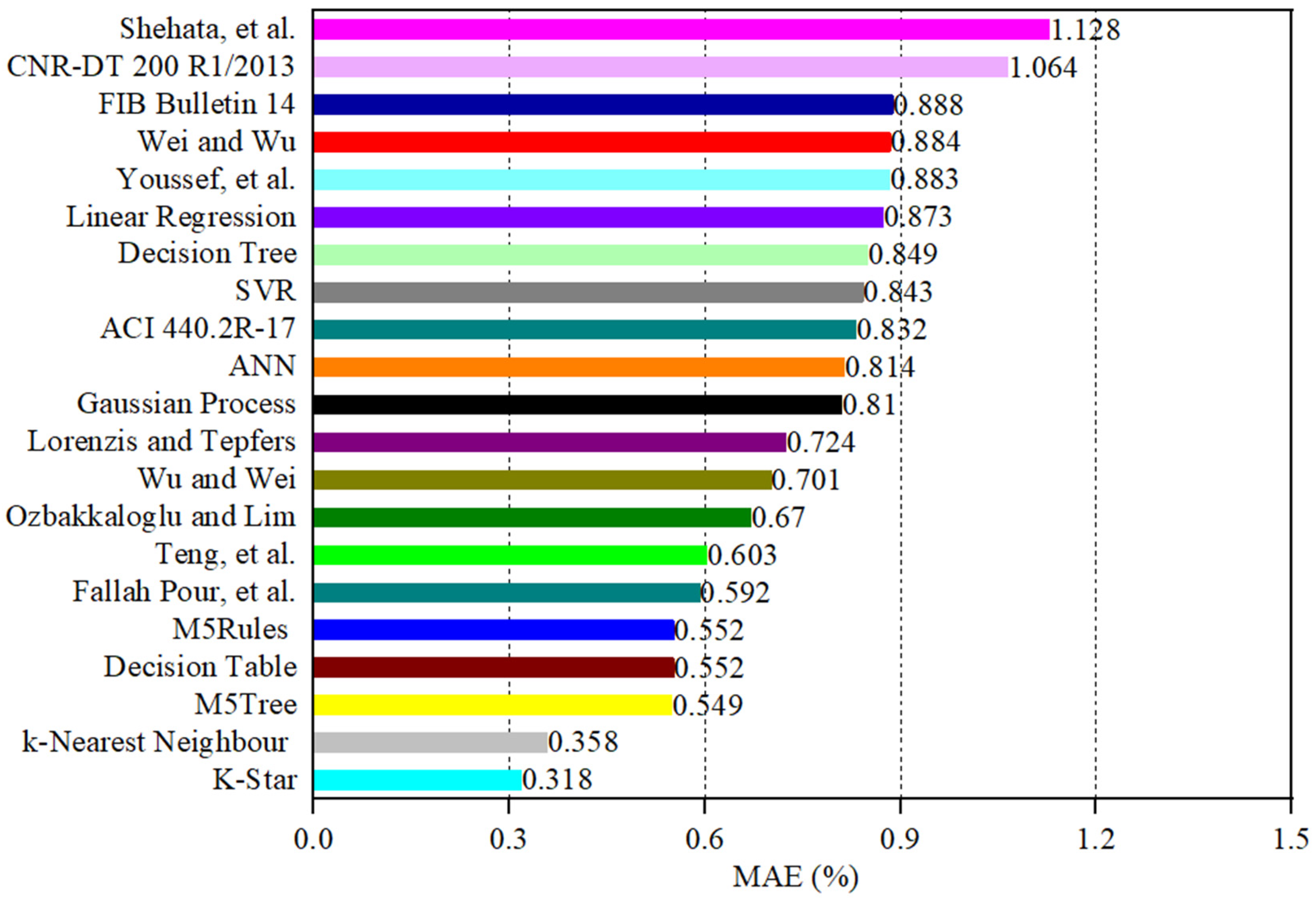

4.2.1. Performance of Empirical Strain and Single ML Models

4.2.2. Performance of Ensemble ML Models

5. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, L. Eccentric compression behavior of partially CFRP wrapped seawater sea-sand concrete columns reinforced with epoxy-coated rebars. Eng. Struct. 2024, 314, 118296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, R.P.; Imjai, T.; Garcia, R.; Chua, Y.S.; Chaudhary, S. Performance of eccentrically loaded low-strength RC columns confined with posttensioned metal straps: An experimental and numerical investigation. Struct. Concr. 2024, 25, 3583–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X. Fatigue Life Prediction of FRP-Strengthened Reinforced Concrete Beams Based on Soft Computing Techniques. Materials 2025, 18, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Zhao, J.; Han, X.; Pan, K.; Yu, R.C.; Wu, Z. Axial Compression Behavior of Circular Seawater and Sea Sand Concrete Columns Reinforced with Hybrid GFRP–Stainless Steel Bars. Materials 2024, 17, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y. Eccentric compression behavior of CFRP partially confined partially encased concrete columns. Structures 2025, 80, 109930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z. Axial compressive behavior of partially CFRP confined seawater sea-sand concrete in circular columns—Part II: A new analysis-oriented model. Compos. Struct. 2020, 246, 112368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.C.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Unified stress-strain model for FRP and actively confined normal-strength and high-strength concrete. J. Compos. Constr. 2015, 19, 04014072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Jin, S.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y. Enhancing Flexural Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Beams Strengthened with Basalt Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Sheets Using Carbon Nanotube-Modified Epoxy. Materials 2024, 17, 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Lim, J.C.; Vincent, T. FRP-confined concrete in circular sections: Review and assessment of stress-strain models. Eng. Struct. 2013, 49, 1068–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Zeng, J.-J.; Gong, Q.-M.; Quach, W.-M.; Gao, W.-Y.; Zhang, L. Design-oriented stress-strain model for FRP-confined ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 318, 126200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.G.; Wu, Y.F.; Li, X.Q. Unified model for evaluating ultimate strain of FRP confined concrete based on energy method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 103, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, O.; Ostrowski, K.A. A Review of External Confinement Methods for Enhancing the Strength of Concrete Columns. Materials 2025, 18, 3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisby, L.A.; Dent, A.J.S.; Green, M.F. Comparison of confinement models for fiber-reinforced polymer-wrapped concrete. ACI Struct. J. 2005, 102, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Lim, J.C. Axial compressive behavior of FRP-confined concrete: Experimental test database and a new design-oriented model. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 55, 607–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.; Teng, J.G. Design-oriented stress–strain model for FRP-confined concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2003, 17, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisby, L.A.; Take, W.A. Strain localisations in FRP-confined concrete: New insights. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Struct. Build. 2009, 162, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, K.A.; Carey, S.A. Shape and “gap” effects on the behavior of variably confined concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.T.; Kim, S.J.; Zhang, H. Behavior and Effectiveness of FRP Wrap in the Confinement of Large Concrete Cylinders. J. Compos. Constr. 2010, 14, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.G.; Jiang, T.; Lam, L.; Luo, Y.Z. Refinement of a design-oriented stress-strain model for FRP-confined concrete. J. Compos. Constr. 2009, 13, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, T.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Influence of fiber orientation and specimen end condition on axial compressive behavior of FRP-confined concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 814–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, A.-D.; Ngo, N.-T.; Nguyen, Q.-T.; Truong, N.-S. Hybrid machine learning for predicting strength of sustainable concrete. Soft Comput. 2020, 24, 14965–14980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.M.; Shah, A.u.R.; Prabhakar, M.N.; Kim, H.S. Deep Learning-Based Microscopic Damage Assessment of Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. Materials 2024, 17, 5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabir, H.; Wu, J.; Dahal, S.; Joo, T.; Garg, N. Automated estimation of cementitious sorptivity via computer vision. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Cai, D.; Gu, S.; Jiang, N.; Li, S. Compressive strength prediction of sleeve grouting materials in prefabricated structures using hybrid optimized XGBoost models. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 476, 141319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarthi, A.; Kaliyamoorthy, B. An interpretable automated optimized machine learning for predicting concrete compressive strength. Expert Syst. Appl. 2026, 298, 129656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.R.; Kannari, L.D.; Senjuntichai, T.; Kaewunruen, S. Optimization of pond-ash-based controlled low-strength materials with lime and superplasticizer via experiments and supervised machine learning. Results Eng. 2026, 29, 108476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W. The Application of Machine Learning in Geotechnical Engineering. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gu, X.; Hong, L.; Han, L.; Wang, L. Comprehensive review of machine learning in geotechnical reliability analysis: Algorithms, applications and further challenges. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 136, 110066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, Y.; Ghanizadeh, A.R.; Safi Jahanshahi, F.; Fakharian, P. Data-driven prediction of axial compression capacity of GFRP-reinforced concrete column using soft computing methods. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 101, 111831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Zhou, J. Application of XGBoost Model Optimized by Multi-Algorithm Ensemble in Predicting FRP-Concrete Interfacial Bond Strength. Materials 2025, 18, 2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, N.-T.; Pham, A.-D.; Truong, T.T.H.; Truong, N.-S.; Huynh, N.-T.; Pham, T.M. An Ensemble Machine Learning Model for Enhancing the Prediction Accuracy of Energy Consumption in Buildings. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2022, 47, 4105–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.-S.; Pham, A.-D. Enhanced artificial intelligence for ensemble approach to predicting high performance concrete compressive strength. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 49, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ene Yalçın, S. Estimation of CO2 Emissions in Transportation Systems Using Artificial Neural Networks, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning: A Comprehensive Approach. Systems 2025, 13, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, W.; Liu, H.; Dong, S.; Zhang, Y. A new method for predicting carbon emissions of paver during construction of asphalt pavement layer based on deep learning and MOVES-NONROAD model. Measurement 2025, 255, 118049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, J.; Zhu, J.; Yang, X. Prediction of the sulfate resistance for recycled aggregate concrete based on ensemble learning algorithms. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 317, 125917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodi, Y.; Mousavi, S.R.; Ghavidel, A.; Sohrabi, M.R.; Rashki, M. Using Response Surface Methodology and providing a modified model using whale algorithm for estimating the compressive strength of columns confined with FRP sheets. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 183, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, A.; Guzelbey, I.H. Neural network modeling of strength enhancement for CFRP confined concrete cylinders. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, M.; Ramezanianpour, A.A. Strength enhancement modeling of concrete cylinders confined with CFRP composites using artificial neural networks. Compos. Part B Eng. 2012, 43, 2990–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderpour, H.; Kheyroddin, A.; Amiri, G.G. Prediction of FRP-confined compressive strength of concrete using artificial neural networks. Compos. Struct. 2010, 92, 2817–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsanadedy, H.M.; Al-Salloum, Y.A.; Abbas, H.; Alsayed, S.H. Prediction of strength parameters of FRP-confined concrete. Compos. Part B Eng. 2012, 43, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Ali, Z.H.; Mukhtar, F.; Al Zand, A.W.; Marhoon, H.A.; Goliatt, L.; Yaseen, Z.M. Coupled extreme gradient boosting algorithm with artificial intelligence models for predicting compressive strength of fiber reinforced polymer- confined concrete. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 134, 108674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, A.; Göğüş, M.T.; Güzelbey, İ.H.; Filiz, H. Soft computing based formulation for strength enhancement of CFRP confined concrete cylinders. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2010, 41, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, A. Modeling strength enhancement of FRP confined concrete cylinders using soft computing. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 5662–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozumder, R.A.; Roy, B.; Laskar, A.I. Support Vector Regression Approach to Predict the Strength of FRP Confined Concrete. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2017, 42, 1129–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Hu, T. Machine Learning Based Compressive Strength Prediction Model for CFRP-confined Columns. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Wang, X.; Hua, L.; Altayeb, M.; Wu, Z.; Niu, F. Prediction of compressive strength of FRP-confined concrete using machine learning: A novel synthetic data driven framework. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 109918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadadi, N.; Roghani, H.; De Caso, F.; El-kenawy, E.-S.M.; Yesha, Y.; Nanni, A. Data-driven PSO-CatBoost machine learning model to predict the compressive strength of CFRP- confined circular concrete specimens. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 198, 111763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, C.; Li, H.; Zhou, J. Explainable machine learning: Compressive strength prediction of FRP-confined concrete column. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 108883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshtegar, B.; Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Gholampour, A. Modeling the behavior of FRP-confined concrete using dynamic harmony search algorithm. Eng. Comput. 2017, 33, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.C.; Karakus, M.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Evaluation of ultimate conditions of FRP-confined concrete columns using genetic programming. Comput. Struct. 2016, 162, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, I.; Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Kisi, O.; Xie, T. Predicting behavior of FRP-confined concrete using neuro fuzzy, neural network, multivariate adaptive regression splines and M5 model tree techniques. Mater. Struct. 2016, 49, 4319–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-F.; Jiang, J.-F. Effective strain of FRP for confined circular concrete columns. Compos. Struct. 2013, 95, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI PRC-440.2-17; Guide for the Design and Construction of Externally Bonded FRP Systems for Strengthening Concrete Structures. ACI (American Concrete Institute): Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2017.

- FIB Bulletin 14; Externally Bonded FRP Reinforcement for RC Structures; FIB (The International Federation for Structure Concrete): Lausanne, Switzerland, 2001.

- CNR-DT 200 R1/2013; Guide for the Design and Construction of Externally Bonded FRP Systems for Strengthening Existing Sructures. CNR-DT (Italian National Research Coucil): Rome, Italy, 2013.

- Shehata, I.A.E.M.; Carneiro, L.A.V.; Shehata, L.C.D. Strength of short concrete columns confined with CFRP sheets. Mater. Struct. 2002, 35, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzis, L.D.; Tepfers, R. Comparative Study of Models on Confinement of Concrete Cylinders with Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. J. Compos. Constr. 2003, 7, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, M.N.; Feng, M.Q.; Mosallam, A.S. Stress–strain model for concrete confined by FRP composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2007, 38, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.-Y.; Wu, Y.-F. Unified stress–strain model of concrete for FRP-confined columns. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 26, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-F.; Wei, Y. General Stress-Strain Model for Steel- and FRP-Confined Concrete. J. Compos. Constr. 2015, 19, 04014069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah Pour, A.; Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Vincent, T. Simplified design-oriented axial stress-strain model for FRP-confined normal- and high-strength concrete. Eng. Struct. 2018, 175, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V.N. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kohavi, R. A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Artifical Intelligence, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–25 August 1995; pp. 1137–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Aire, C.; Gettu, R.; Casas, J.R.; Marques, S.; Marques, D. Concrete laterally confined with fibre-reinforced polymers (FRP): Experimental study and theoretical model. Mater. Construcción 2010, 60, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akogbe, R.-K.; Wu, Z.-M.; Liang, M.D. Size Effect of Axial Compressive Strength of CFRP Confined Concrete Cylinders. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2011, 5, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salloum, M.; Siddiqui, N. Compressive strength prediction model for FRPconfined concrete. In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Reinforcement for Concrete Structures, Sydney, Australia, 13–15 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Benzaid, R.; Mesbah, H.; Chikh, N.E. FRP-confined Concrete Cylinders: Axial Compression Experiments and Strength Model. J. Reinf. Plast. Compost. 2010, 29, 2469–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthet, J.F.; Ferrier, E.; Hamelin, P. Compressive behavior of concrete externally confined by composite jackets. Part A: Experimental study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2005, 19, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisby, L.A.; Take, W.A.; Cabe, A.M. Quantifying strain variation FRP confined using digital image correlation: Proof-of-concept and initial results. In Proceedings of the First Asia-Pacific Conference on FRP in Structures, Hong Kong, China, 12–14 December 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bisby, L.A.; Chen, J.F.; Li, S.Q.; Stratford, T.J.; Cueva, N.; Crossling, K. Strengthening fire-damaged concrete by confinement with fibre-reinforced polymer wraps. Eng. Struct. 2011, 33, 3381–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campione, G.; Miraglia, N.; Scibilia, N. Comprehensive Behaviour of R.C. Members Strengthened With Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic Layers. In Earthquake Resistant Engineering Structures III; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2001; pp. 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Shawn, A.C.; Kent, A.H. Axial Behavior and Modeling of Confined Small-, Medium-, and Large-Scale Circular Sections with Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Jackets. ACI Struct. J. 2005, 102, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Sheikh, S.A. Experimental Study of Normal- and High-Strength Concrete Confined with Fiber-Reinforced Polymers. J. Compos. Constr. 2010, 14, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demers, M.; Neale, K.W. Strengthening of concrete columns with unidirectional composite sheets. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Short and Medium Span Bridges Engineering, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–11 August 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Elsanadedy, H.M.; Al-Salloum, Y.A.; Alsayed, S.H.; Iqbal, R.A. Experimental and numerical investigation of size effects in FRP-wrapped concrete columns. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 29, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdil, B.; Akyuz, U.; Yaman, I.O. Mechanical behavior of CFRP confined low strength concretes subjected to simultaneous heating–cooling cycles and sustained loading. Mater. Struct. 2012, 45, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Kocman, M.; Kretschmer, T. Hybrid FRP Confined Concrete Columns; School of Civil, Environmental and Mining Engineering, University of Adelaide: Adelaide, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.F.; Bisby, L.A.; Fam, A.Z.; Kodur, V.K.R. FRP confined concrete columns: Behaviour under extreme conditions. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2006, 28, 928–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, T.G.; Slattery, K.T. Advanced composite confinement of concrete. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Advanced Composite Materials in Bridges and Structures, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada, October 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Harries, K.A.; Kharel, G. Behavior and modeling of concrete subject to variable confining pressure. ACI Mater. J. 2002, 99, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosotani, M.; Kawashima, K.; HOSHIKUMA, J. A model for confinement effect for concrete cylinders confined by carbon fiber sheets. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Earthquake Engineering Frontiers in Transportation Facilities, Buffalo, NY, USA, 10–11 March 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Howie, I.; Karbhari, V. Effect of Materials Architecture on Strengthening Efficiency of Composite Wraps for Deteriorating Columns in the North-East. In Proceedings of the 3rd Materials Engineering Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 13–16 November 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ilki, A.; Kumbasar, N.; Koc, V. Strength and deformability of low strength concrete confined by carbon fiber composite sheets. In Proceedings of the ASCE 15th Engineering Mechanics Conference, New York, NY, USA, 2–5 June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ilki, A.; Kumbasar, N.; Koc, V. Low Strength Concrete Members Externally Confined with FRP Sheets. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2004, 18, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabinis, A.I.; Rousakis, T.C. Concrete confined by FRP material: A plasticity approach. Eng. Struct. 2002, 24, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, G.; Tabbara, M. Corner effects in CFRP-wrapped square columns. Mag. Concr. Res. 2004, 56, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karantzikis, M.; Papanicolaou Catherine, G.; Antonopoulos Costas, P.; Triantafillou Thanasis, C. Experimental Investigation of Nonconventional Confinement for Concrete Using FRP. J. Compos. Constr. 2005, 9, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, S.; Inazumi, M.; Kaku, T. Evaluation of confining effects of CFRP sheets on reinforced concrete members. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Composites in Infrastructure, Tucson, AZ, USA, 5–7 January 1998; pp. 343–355. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Yi, C.K.; Jeong, H.S.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, J.K. Compressive Response of Concrete Confined with Steel Spirals and FRP Composites. J. Compos. Mater. 2010, 44, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Wu, Z.-M.; Ueda, T.; Zheng, J.-J.; Akogbe, R. Experiment and modeling on axial behavior of carbon fiber reinforced polymer confined concrete cylinders with different sizes. J. Reinf. Plast. Compost. 2012, 31, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Hoskin, A.; Fam, A.; Nanni, A. Influence of concrete strength on confinement effectiveness of fiber-reinforced polymer circular jackets. ACI Struct. J. 2006, 102, 305–306. [Google Scholar]

- Micelli, F.; Myers, J.; Murthy, S. Effect of environmental cycles on concrete cylinders confined with FRP. In Proceedings of the International Conference: Composites in Constructions, Capri, Italy, 20–21 July 2001; pp. 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi, K. Estimation of Strengthening Effects with Carbon Fiber Sheet for Concrete Column. In Proceedings of the Third International Symposium on Non-Metallic (FRP) Reinforcement for Concrete Structures, Sapporo, Japan, 14–16 October 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi, K.; Inoue, S.; Kuroda, T.; Kobayashi, A. Strengthening effects of concrete column with carbon fiber sheet. Trans. Jpn. Concr. Inst. 1999, 21, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Modarelli, R.; Micelli, F.; Manni, O. FRP-Confinement of Hollow Concrete Cylinders and Prisms. ACI Symp. Publ. 2005, 230, 1029–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, L.M. Stress-Strain Behavior of Concrete Confined by Carbon Fiber Jacketing. Master’s Thesis, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Picher, F.; Rochette, P.; Labossiere, P. Confinement of concrete cylinders with CFRP. In Proceedings of the ICCI’96 The First International Conference on Composites in Infrastructures, Tucson, AZ, USA, 15–17 January 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Piekarczyk, J.; Piekarczyk, W.; Blazewicz, S. Compression strength of concrete cylinders reinforced with carbon fiber laminate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 2365–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochette, P.; Labossière, P. Axial testing of rectangular column models confined with composites. J. Compos. Constr. 2000, 4, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, N.; Pantelides, C.P. Short and Medium Term Durability Evaluation of FRP-Confined Circular Concrete. J. Compos. Constr. 2006, 10, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousakis, T.; You, C.-S.; De Lorenzis, L.; Tamuvzs, V.; Tepfers, R. Concrete cylinders confined by CFRP sheets subjected to cyclic axial compressive load. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Fiber Reinforced Polymer Reinforced for Reinforced Concrete Structures, Singapore, 8–10 July 2003; pp. 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarosa, D.; Filho, A.C.; Beber, A.J.; Campagnolo, J.L. Concrete Columns Confined with CFRP Sheets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on FRP Composites in Civil Engineering, Hong Kong, China, 12–15 December 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shahawy, M.; Mirmiran, A.; Beitelman, T. Tests and modeling of carbon-wrapped concrete columns. Compos. Part B Eng. 2000, 31, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Gu, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhang, W. Mechanical Behavior of FRP-Strengthened Concrete Columns Subjected to Concentric and Eccentric Compression Loading. J. Compos. Constr. 2013, 17, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, J.F.; Owen, L.M. The Influence of Concrete Strength and Confinement Type on the Response of FRP-Confined Concrete Cylinders. ACI Symp. Publ. 2026, 238, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, A.; Shahawy, H.; Samaan, M.; Echary, H.E.; Mastrapa, J.C.; Pico, O. Effect of Column Parameters on FRP-Confined Concrete. J. Compos. Constr. 1998, 2, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrapa, J.C. Effect of Construction Bond on Confinement with Fiber Composites. Master’s Thesis, University of Central Florida, Prlando, FL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Matthys, S.; Taerwe, L.; Audenaert, K. Tests on Axially Loaded Concrete Columns Confined by Fiber Reinforced Polymer Sheet Wrapping. ACI Symp. Publ. 1999, 188, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wu, H. Compressive behavior of concrete confined by carbon fiber composite jackets. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2000, 12, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.; Teng, J. Ultimate Condition of Fiber Reinforced Polymer-Confined Concrete. J. Compos. Constr. 2004, 8, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdmanis, V.; De Lorenzis, L.; Rousakis, T.; Tepfers, R. Behaviour and capacity of CFRP-confined concrete cylinders subjected to monotonic and cyclic axial compressive load. Struct. Concr. 2007, 8, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Nakamura, H.; Honda, Y.; Toyoshima, M.; Iso, M.; Hujimaki, T.; Kaneto, M.; Shirai, N. Confinement Effect of FRP Sheet on Strength and Ductility of Concrete Cylinders under Uniaxial Compression “Jointly Warked”. In Proceedings of the Non-Metallic (FRP) Reinforcement for Concrete Structures: Proceedings of the Third International Symposium, Sapporo, Japan, 14–16 October 1997; pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T.; Teng, J.G. Analysis-oriented stress–strain models for FRP–confined concrete. Eng. Struct. 2007, 29, 2968–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.L.; Yu, T.; Teng, J.G.; Dong, S.L. Behavior of FRP-confined concrete in annular section columns. Compos. Part B Eng. 2008, 39, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wu, Z.S.; Lu, Z.T.; Ando, Y.B. Structural Performance of Concrete Confined with Hybrid FRP Composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compost. 2008, 27, 1323–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Akin, E. Behavior of FRP-Confined Normal- and High-Strength Concrete under Cyclic Axial Compression. J. Compos. Constr. 2012, 16, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.-G.; Bai, Y.-L.; Teng, J.G. Behavior and Modeling of Concrete Confined with FRP Composites of Large Deformability. J. Compos. Constr. 2011, 15, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, B.; Bakhshi, M.; Motavalli, M.; Shekarchi, M. Experimental modeling of GFRP confined concrete cylinders subjected to axial loads. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Fiber Reinforced Polymer Reinforcement for Reinforced Concrete Structures, Patras, Greece, 16–18 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bullo, S. Experimental study of the effects of the ultimate strain of fiber reinforced plastic jackets on the behavior of confined concrete. In Proceedings of the International Conference Composites in Constructions, Cosenza, Italy, 16–19 September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Comert, M.; Goksu, C.; Ilki, A. Towards a tailored stress–strain behavior for FRP confined low strength concrete. In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Reinforcement for Concrete Structures, Sydney, Australia, 13–15 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nanni, A.; Bradford, N.M. FRP jacketed concrete under uniaxial compression. Constr. Build. Mater. 1995, 9, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousakis, T.; Tepfers, R. Experimental investigation of concrete cylinders confined by carbon FRP sheets, under monotonic and cyclic axial compressive load. Res. Rep 2001, 44, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.A.; Rodrigues, C.C. Size and Relative Stiffness Effects on Compressive Failure of Concrete Columns Wrapped with Glass FRP. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2006, 18, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, R.; Pinzelli, R. Confinement of concrete columns with FRP sheets. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Fibre-Reinforced Plastics for Reinforced Concrete Structures, Cambridge, UK, 16–18 July 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tamuzs, V.; Valdmanis, V.; Tepfers, R.; Gylltoft, K. Stability analysis of CFRP-wrapped concrete columns strengthened with external longitudinal CFRP sheets. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2008, 44, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.G.; Yu, T.; Wong, Y.L.; Dong, S.L. Hybrid FRP-concrete-steel tubular columns: Concept and behavior. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, T.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Influence of concrete strength and confinement method on axial compressive behavior of FRP confined high- and ultra high-strength concrete. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 50, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Wu, H.L. Size effect of concrete short columns confined with aramid FRP jackets. J. Compos. Constr. 2011, 15, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-F.; Jiang, C. Effect of load eccentricity on the stress–strain relationship of FRP-confined concrete columns. Compos. Struct. 2013, 98, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Pantelides, C.P. Fiber-reinforced polymer jacketed and shape-modified compression members: II—Model. ACI Struct. J. 2006, 103, 894–903. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Ye, L.; Mai, Y.-W. A Study on Polymer Composite Strengthening Systems for Concrete Columns. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2000, 7, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Reference | Compressive Strength Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ACI 440.2R-17 [53] | |

| 2 | FIB Bulletin 14 [54] | |

| 3 | CNR-DT 200 R1/2013 [55] | |

| 4 | Shehata et al. [56] | |

| 5 | Lorenzis and Tepfers [57] | |

| 6 | Youssef et al. [58] | |

| 7 | Teng et al. [19] | |

| 8 | Wei and Wu [59] | |

| 9 | Ozbakkaloglu and Lim [14] | |

| 10 | Wu and Wei [60] | |

| 11 | Fallah Pour et al. [61] |

| No. | Model | Indicator | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | SI | |||

| 1 | ACI 440.2R-17 [53] | 0.786 | 43.4 | 1.398 | 0.832 | 0.503 |

| 2 | FIB Bulletin 14 [54] | 0.622 | 61.6 | 1.338 | 0.888 | 0.609 |

| 3 | CNR-DT 200 R1/2013 [55] | 0.659 | 46.8 | 1.604 | 1.064 | 0.658 |

| 4 | Shehata et al. [56] | 0.514 | 87.2 | 1.654 | 1.128 | 0.905 |

| 5 | Lorenzis and Tepfers [57] | 0.793 | 36.6 | 1.043 | 0.724 | 0.352 |

| 6 | Youssef et al. [58] | 0.767 | 50.6 | 1.908 | 0.883 | 0.665 |

| 7 | Teng et al. [19] | 0.811 | 39.4 | 0.857 | 0.603 | 0.279 |

| 8 | Wei and Wu [59] | 0.726 | 42.7 | 2.126 | 0.884 | 0.668 |

| 9 | Ozbakkaloglu and Lim [14] | 0.787 | 42.6 | 1.153 | 0.670 | 0.383 |

| 10 | Wu and Wei [60] | 0.768 | 39.3 | 1.255 | 0.701 | 0.399 |

| 11 | Fallah Pour et al. [61] | 0.790 | 39.6 | 0.892 | 0.592 | 0.283 |

| 12 | Linear Regression—Testing | 0.444 | 68.8 | 1.23 | 0.873 | 0.619 |

| Linear Regression—(Training) | (0.484) | (66.8) | (1.22) | (0.852) | ||

| 13 | Gaussian Process—Testing | 0.337 | 66.5 | 1.043 | 0.810 | 0.543 |

| Gaussian Process—(Training) | (0.397) | (67.4) | (1.310) | (0.886) | ||

| 14 | ANN—Testing | 0.671 | 63.8 | 1.051 | 0.814 | 0.532 |

| ANN—(Training) | (0.786) | (57.4) | (0.928) | (0.725) | ||

| 15 | SVR—Testing | 0.437 | 58.7 | 1.281 | 0.843 | 0.564 |

| SVR—(Training) | (0.469) | (57.3) | (1.302) | (0.828) | ||

| 16 | Decision Tree—Testing | 0.520 | 66.9 | 0.966 | 0.849 | 0.546 |

| Decision Tree—(Training) | (0.589) | (71.3) | (1.149) | (0.761) | ||

| 17 | M5Tree—Testing | 0.786 | 40.9 | 0.979 | 0.549 | 0.289 |

| M5Tree—(Training) | (0.895) | (33.1) | (0.639) | (0.452) | ||

| 18 | M5Rules—Testing | 0.773 | 40.5 | 0.817 | 0.552 | 0.255 |

| M5Rules—Training | (0.890) | (35.2) | (0.637) | (0.460) | ||

| 19 | Decision Table—Testing | 0.801 | 41.3 | 0.778 | 0.552 | 0.252 |

| Decision Table—(Training) | (0.890) | (27.3) | (0.634) | (0.396) | ||

| 20 | k-Nearest Neighbor—Testing | 0.912 | 25.4 | 0.550 | 0.358 | 0.043 |

| k-Nearest Neighbor—(Training) | (0.993) | (4.4) | (0.166) | (0.079) | ||

| 21 | K-Star—Testing | 0.934 | 23.2 | 0.472 | 0.318 | 0 |

| K-Star—(Training) | (0.991) | (6.13) | (0.199) | (0.110) | ||

| No | Model | Indicators | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | SI | ||||

| Original | K-Star | Testing | 0.934 | 23.2 | 0.472 | 0.318 | 0.0250 |

| Training | 0.991 | 6.13 | 0.199 | 0.110 | |||

| Voting | K-Star + k-NN | Testing | 0.932 | 22.9 | 0.475 | 0.318 | 0.0220 |

| Training | 0.992 | 5.2 | 0.175 | 0.092 | |||

| K-Star + k-NN + DT | Testing | 0.932 | 23.0 | 0.478 | 0.325 | 0.0396 | |

| Training | 0.984 | 11.1 | 0.259 | 0.168 | |||

| K-Star + k-NN + DT + M5Rules | Testing | 0.923 | 25.2 | 0.522 | 0.348 | 0.1785 | |

| Training | 0.979 | 15.1 | 0.317 | 0.215 | |||

| Stacking | K-Star + k-NN | Testing | 0.935 | 23.1 | 0.467 | 0.312 | 0.0067 |

| Training | 0.992 | 5.9 | 0.180 | 0.099 | |||

| K-Star + k-NN + DT | Testing | 0.936 | 23.2 | 0.465 | 0.312 | 0.0065 | |

| Training | 0.990 | 7.6 | 0.197 | 0.120 | |||

| K-Star + k-NN + DT + M5Rules | Testing | 0.887 | 28.4 | 0.591 | 0.409 | 0.4332 | |

| Testing | 0.950 | 19.0 | 0.448 | 0.282 | |||

| Bagging | K-Star | Testing | 0.905 | 27.0 | 0.551 | 0.366 | 0.2825 |

| Training | 0.981 | 12.4 | 0.276 | 0.172 | |||

| k-NN | Testing | 0.927 | 25.1 | 0.508 | 0.349 | 0.1615 | |

| Training | 0.980 | 12.7 | 0.302 | 0.189 | |||

| DT | Testing | 0.883 | 31.7 | 0.619 | 0.429 | 0.5721 | |

| Training | 0.944 | 23.6 | 0.478 | 0.318 | |||

| M5Rules | Testing | 0.833 | 38.2 | 0.748 | 0.508 | 1.00 | |

| Training | 0.884 | 32.7 | 0.668 | 0.434 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nguyen, Q.T.; Pham, A.D.; Truong, Q.C.; Nguyen, C.L.; Truong, N.S.; Mai, A.D. Investigation of Ensemble Machine Learning Models for Estimating the Ultimate Strain of FRP-Confined Concrete Columns. Materials 2026, 19, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010189

Nguyen QT, Pham AD, Truong QC, Nguyen CL, Truong NS, Mai AD. Investigation of Ensemble Machine Learning Models for Estimating the Ultimate Strain of FRP-Confined Concrete Columns. Materials. 2026; 19(1):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010189

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Quang Trung, Anh Duc Pham, Quynh Chau Truong, Cong Luyen Nguyen, Ngoc Son Truong, and Anh Duc Mai. 2026. "Investigation of Ensemble Machine Learning Models for Estimating the Ultimate Strain of FRP-Confined Concrete Columns" Materials 19, no. 1: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010189

APA StyleNguyen, Q. T., Pham, A. D., Truong, Q. C., Nguyen, C. L., Truong, N. S., & Mai, A. D. (2026). Investigation of Ensemble Machine Learning Models for Estimating the Ultimate Strain of FRP-Confined Concrete Columns. Materials, 19(1), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010189