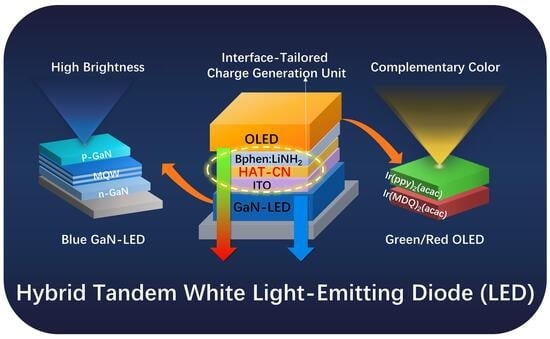

Hybrid Tandem White Light-Emitting Diodes Based on GaN and Organic Emitters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiments and Characterizations

2.1. Device Fabrication

2.2. Characterizations

3. Results and Discussion

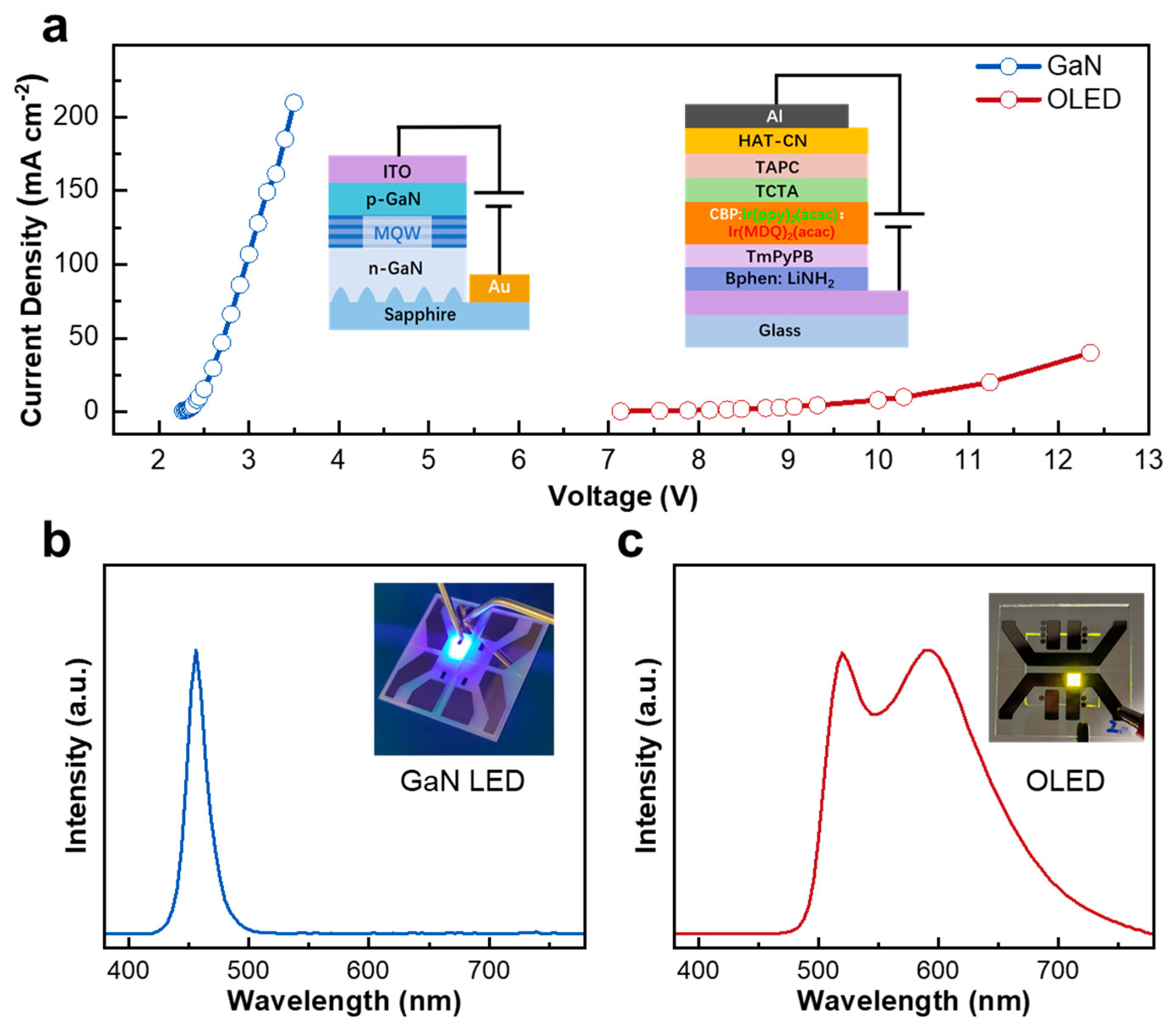

3.1. EL Performances of Single LEDs

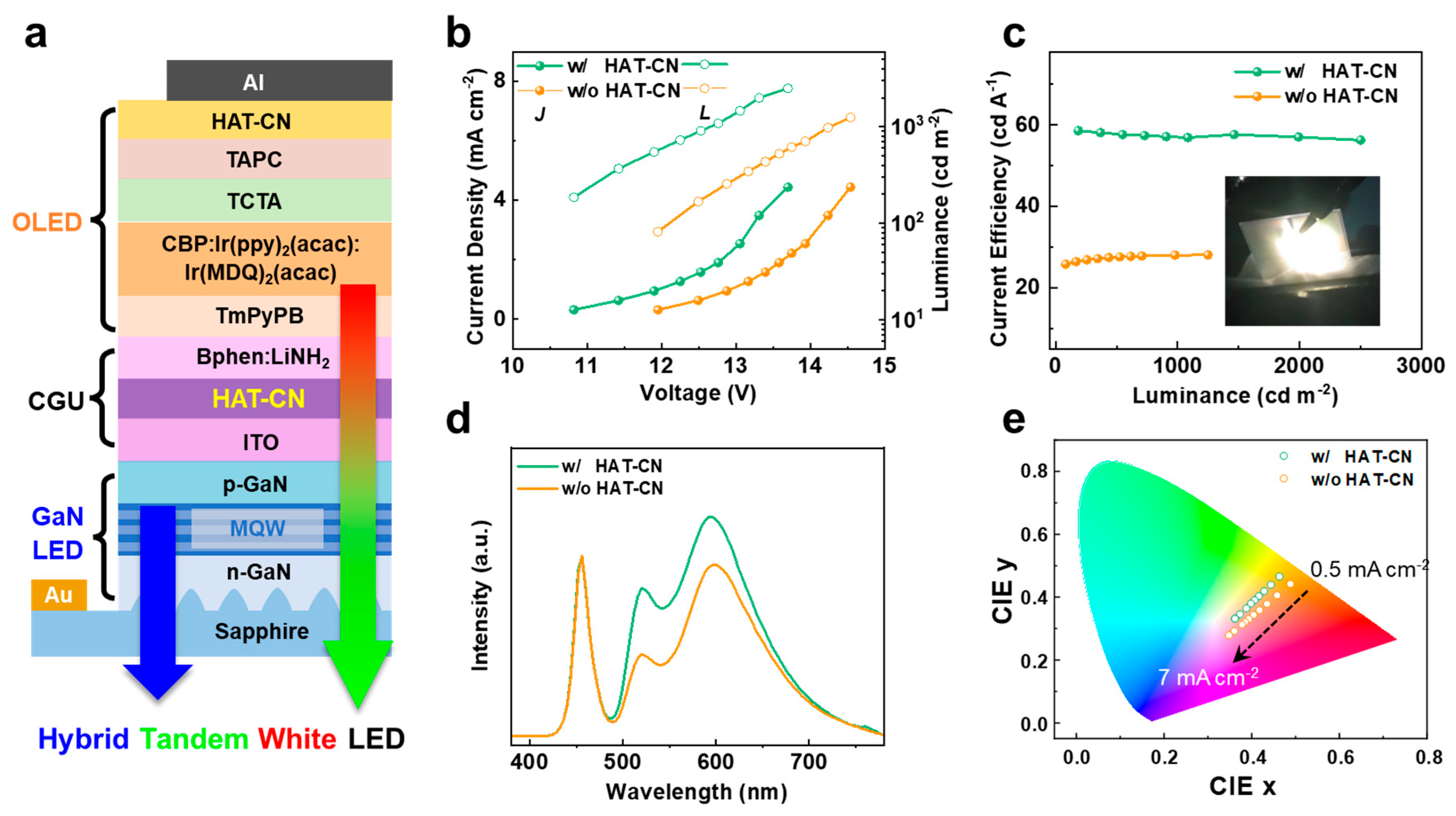

3.2. EL Performances of Hybrid Tandem White LEDs

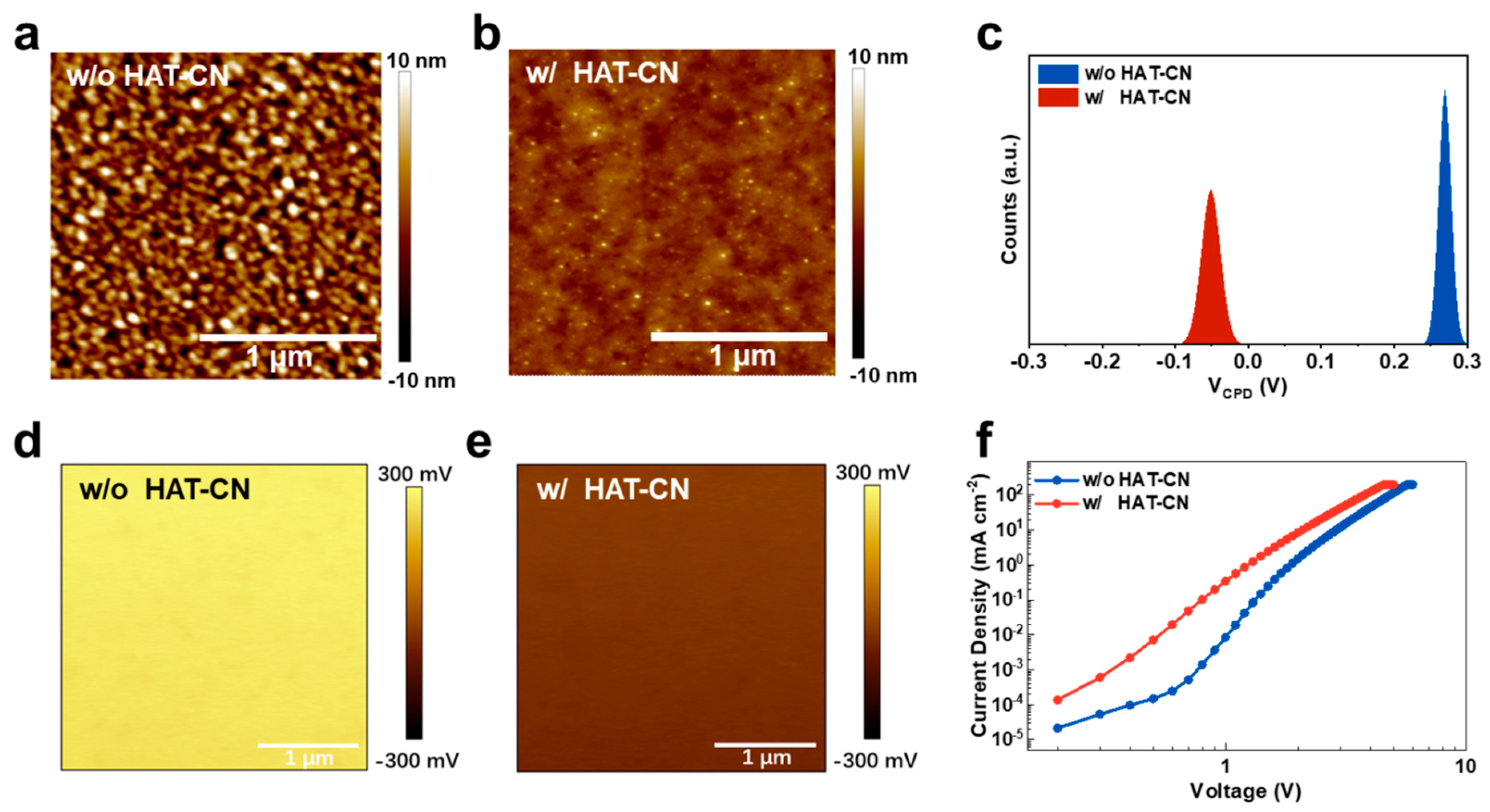

3.3. Interfacial Mechanisms Underlying the Improved CGU Performance

3.4. Other Hybrid Tandem Strategy: Blue–Yellow White LEDs

3.5. Advantages and Limitations of CGU and HT-LED

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jing, Y.; Yao, M.; Yang, M.; Li, M.; Ding, H.; Yang, G.; Zhang, R.; Han, D.; Liu, H.; Zhong, H. Photolithographic fabrication of high-resolution Micro-QLEDs towards color-conversion microdisplay. Light Sci. Appl. 2025, 14, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Xi, M.; Bai, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Zhu, X.; He, Y.; He, B.; et al. Micro-LED Microdisplays Driven by Carbon Nanotube Active-Matrix Backplanes. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 22837−22848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Lv, R.; Chen, Z.; Guo, W.; Guo, T.; Ji, Y.; Song, X.; et al. One-Step, Mask-Free, Rapid Laser Writing Fabrication of Electroluminescent Perovskite@Oxide Pixels for Ultra-High PPI, Efficient Micro-QLEDs. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2413811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Jiang, J.; Qin, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, D.-K. Patterned waveguide liquid crystal displays. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 41693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Lv, G.Q.; Li, J.-J.; Hu, Z.-A.; Wang, Z.; Feng, Q.B. Analyzing the effect of temperature on optical performance of dual-layer liquid crystal displays. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 2021, 29, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Yu, Y.-J.; Feng, Z.-Q.; Qu, Z.-H.; Zuo, P.; Yan, H.-Y.; Jiang, Z.-Q.; Zhou, D.-Y.; Liao, L.-S. A red thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitter with mitigated efficiency roll-off via a p-stacked multiple donor–acceptor structure. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 6858–6864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-R.; Yang, Y.-J.; Ge, S.-J.; Qu, Y.-K.; Yan, H.-Y.; Jiang, H.-X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, D.-Y.; Liao, L.-S.; Jiang, Z.-Q. B─N Covalent Bonds and Twin-Spiro Fused Design Strategy for the Construction of Narrowband Multiple Resonance Emitters. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2507553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Min, J.; Reddeppa, M.; Malhotra, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Sun, K.; Mi, Z. An Ultrahigh Efficiency Excitonic Micro-LED. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 1680–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Feng, F.; Zhang, J.; Huang, S.; Yeung, F.; Tseng, M.; Wong, M.; Kwok, H.S.; et al. Vertical GaN-On-GaN Micro-LEDs for Near-Eye Displays. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e06784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Acosta, M.A.; Martinez-Gutiérrez, H.; Martínez-González, C.L.; Torres-SanMiguel, C.R.; Trejo-Valdez, M.; Torres-Torres, C. Fractional and Chaotic Electrical Signatures Exhibited by Random Carbon Nanotube Networks. Phys. Scr. 2018, 93, 125801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kwon, Y.-J.; Choi, H.-E.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, M.; Lee, J.-K.; Jang, G.; Kim, T.; Lee, J.Y.; et al. Vacuum-Depositable Fluorinated Photoresist toward Organic Light-Emitting Diode (OLED) Patterning. ACS Mater. Lett. 2025, 7, 2988–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kim, K.; Kwon, O.; Jung, J.; Park, J.K.; Kim, D.H.; Jung, K. Fine metal mask material and manufacturing process for high-resolution active-matrix organic light-emitting diode displays. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 2020, 28, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Kim, H.M.; Lee, H.J.; Jin, S.H. Scalable Demonstration of Negligible Hysteresis of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistors via Dual-Stacked Gate Dielectrics for Micro-Light-Emitting Diode Display Application. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 2025, 19, 2500240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, C.A.; Meitl, M.A.; Raymond, B.; Radauscher, E.; Cok, R.; Bonafede, S.; Gomez, D.; Moore, T.; Prevatte, C.; Fisher, B.; et al. Emissive displays with transfer-printed assemblies of 8 μm × 15 μm inorganic light-emitting diodes. Photonics Res. 2017, 5, A23–A29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.A.; Ryu, H.; Park, S.; Kim, T.K.; Min, S.; Shin, S.H.; Thaalbi, H.; Tariq, F.; Lee, S.H.; Jang, H.W.; et al. Monolithic Integration of GaN Thin Film and GaN Nanorods Pixels: Facile Growth of InGaN/GaN Quantum Wells for the Realization of Full Color Micro-LED Display. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, 2500271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Guo, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Cao, R.; Gong, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, N.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; et al. Wafer-Scale Micro-LEDs Transferred onto an Adhesive Film for Planar and Flexible Displays. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2020, 5, 2000549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Avrutin, V.; Izyumskaya, N.; Özgur, Ü.; Morkoç, H. Micro-LEDs, a Manufacturability Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tao, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, P.; Lv, J.; Qin, Y.; Wang, W.; Zeng, Q.; et al. Microfluidics-based quantum dot color conversion layers for full-color micro-LED display. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 118, 173501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Sun, S.; Luo, W.; He, W.; Wang, J.; Shi, X.; Fung, M.-K. Hybrid Tandem White OLED with Long Lifetime and 150 lm W−1 in Luminous Efficacy Based on TADF Blue Emitter Stabilized with Phosphorescent Red Emitter. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020, 8, 2000727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Ren, Z.; Wang, S.-F.; Shi, X.-B.; Liu, W.-Z.; Feng, Z.-Q.; Zhou, D.-Y.; Chou, P.-T.; Liao, L.-S. Antinode-centre near-infrared tandem OLEDs enabled by ultrathin emissive layers. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 167897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Tong, K.-N.; Shi, K.; He, W.; Huang, M.; Yan, J.; Li, S.; Jin, Z.; Wang, X.; Jung, S.; et al. Exceptionally high brightness and long lifetime of efficient blue OLEDs for programmable active-matrix display. Light Sci. Appl. 2025, 14, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Niu, Y.; Gong, C.; Shi, W.; Yang, X.; Wei, B.; Wong, W.-Y. High-Performance Inverted Tandem OLEDs with the Charge Generation Layer based on MoOx and Ag Doped Planar Heterojunction. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2022, 10, 2200984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Yang, H.I.; Kim, D.K.; Pode, R.; Kwon, J.H. Optical performance evaluation of blue tandem top-emitting OLED device. Org. Electron. 2023, 118, 106810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Chen, G.; Nie, J.; Que, S.; Song, S.-H.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Hybrid Device of Blue GaN Light-Emitting Diodes and Organic Light-Emitting Diodes with Color Tunability for Smart Lighting Sources. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 5502–5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, Y.P.; Kim, T.W. Efficiency Enhancement of Tandem Organic Light-Emitting Devices Fabricated Utilizing an 1,4,5,8,9,11-Hexaazatriphenylene-Hexacarbonitrile Charge-Generation Layer. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 7717–7721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseynova, G.; Lee, J.H.; Gasonoo, A.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, J. Efficient tandem organic light-emitting diode with fluorinated hexaazatrinaphthylene charge generation layer. J. Inf. Disp. 2022, 23, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.-H.; Xu, J.-Z.; Tang, Y.-B.; Liu, W.-Z.; Meng, S.-G.; Zhou, D.-Y.; Liao, L.-S. Interfacial Dipole Engineering for Energy Level Alignment in NiOx-Based Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes. Small 2024, 20, 2403325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Xia, Y.; Li, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, H. Recent Progress in Organic Dual-Emission Materials for White Organic Light Emitting Diodes (WOLEDs) from Single Small-Molecule Components. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 11017–11039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Sun, Y.-Q.; Chen, H.; Zu, F.-S.; Wang, Z.-K.; Liao, L.-S. A novel intermediate connector with improved charge generation and separation for large-area tandem white organic lighting devices. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 10403–10408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-L.; Wang, Z.B.; Helander, M.G.; Qiu, J.; Puzzo, D.P.; Lu, Z.H. Enhancing the efficiency of simplified red phosphorescent organic light emitting diodes by exciton harvesting. Org. Electron. 2012, 13, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, S.; Sun, Q.; Huang, C.; Fung, M.-K. Highly Efficient White Organic Light-Emitting Diodes with Ultrathin Emissive Layers and a Spacer-Free Structure. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.S.; Lee, J.Y. Engineering of Mixed Host for High External Quantum Efficiency above 25% in Green Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Device. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 3970–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, J.-Z.; Zhu, X.-Z.; Zhai, F.; Liu, W.-Z.; Zhou, D.-Y.; Liao, L.-S. Hybrid Tandem White Light-Emitting Diodes Based on GaN and Organic Emitters. Materials 2025, 18, 5684. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245684

Xu J-Z, Zhu X-Z, Zhai F, Liu W-Z, Zhou D-Y, Liao L-S. Hybrid Tandem White Light-Emitting Diodes Based on GaN and Organic Emitters. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5684. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245684

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jin-Zhe, Xiao-Zhao Zhu, Feng Zhai, Wei-Zhi Liu, Dong-Ying Zhou, and Liang-Sheng Liao. 2025. "Hybrid Tandem White Light-Emitting Diodes Based on GaN and Organic Emitters" Materials 18, no. 24: 5684. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245684

APA StyleXu, J.-Z., Zhu, X.-Z., Zhai, F., Liu, W.-Z., Zhou, D.-Y., & Liao, L.-S. (2025). Hybrid Tandem White Light-Emitting Diodes Based on GaN and Organic Emitters. Materials, 18(24), 5684. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245684