Progress in Charge Transfer in 2D Metal Halide Perovskite Heterojunctions: A Review

Highlights

- This review summarizes charge transfer mechanisms and interfacial coupling effects in two-dimensional (2D) metal halide perovskite (MHP)-based heterojunctions, with a focus on their roles in governing device performance.

- Ultrafast carrier dynamics and band-engineering strategies are systematically discussed, highlighting effective approaches to enhance charge separation and suppress nonradiative recombination.

- Interface engineering and molecular passivation are identified as key routes to improving the stability and operational performance of 2D MHP-based devices.

- The presented insights provide guidance for the rational design of flexible, high-efficiency optoelectronic and quantum photonic devices.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Architecture of Metal Halide Perovskite-Based Heterojunctions

3. Ultrafast Optical Processes in Metal Halide Perovskite Heterojunctions

3.1. Ultrafast Spectroscopic Techniques

3.2. Metal Halide Perovskite/Graphene Heterojunctions

3.3. Metal Halide Perovskite/TMDs Heterojunctions

3.4. Metal Halide Perovskite/Metal Oxide Heterojunctions

4. Applications of Metal Halide Perovskite-Based Heterojunctions in Optoelectronic Devices

4.1. Solar Cells

4.2. Photodetectors

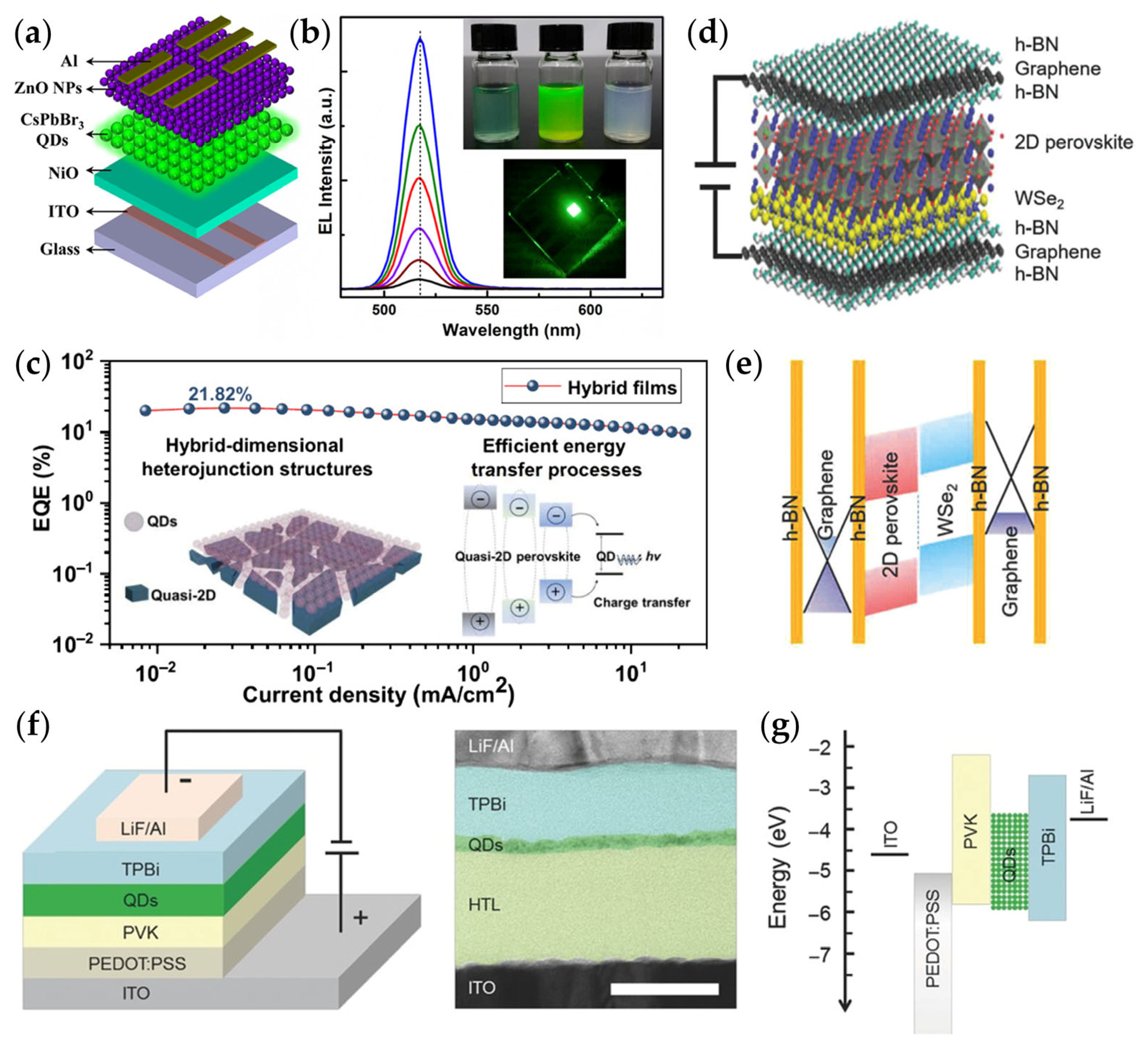

4.3. Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs)

4.4. Field-Effect Transistors (FETs)

5. Summary and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| MHPs | Metal halide perovskites |

| LEDs | Light-emitting devices |

| PSCs | perovskite solar cells |

| PLQY | Photoluminescence quantum yield |

| vdWs | van der Waals |

| h-BN | Hexagonal boron nitride |

| TMDs | Transition metal dichalcogenides |

| TA | Transient absorption |

| THz | Terahertz |

| PL | Photoluminescence |

| MA+ | CH3NH3+ |

| TEA+ | (C2H5)4N+ |

| CBM | Conduction band minimum |

| VBM | Valence band maximum |

| Tc | Effective temperature |

| TRTS | Time-resolved THz spectroscopy |

| TRPL | Time-resolved photoluminescence spectroscopy |

| OPA | Optical parametric amplifier |

| PB | Photobleaching |

| SE | Stimulated emission |

| PIA | Photoinduced absorption |

| OPTP | Optical pump-THz probe |

| ETL | Electron transport layer |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| HTL | Hole transport layer |

| RPP | Ruddlesden–Popper perovskites |

| QDs | Quantum dots |

| ITO | Indium tin oxide |

| PCE | Power conversion efficiency |

| EQE | External quantum efficiency |

| I–V | Current-voltage |

| D* | detectivity |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| FETs | Field-Effect Transistors |

| NC | Nanocrystal |

| PNCs | Perovskite nanocrystals |

References

- Rose, G. De Novis Quibusdam Fossilibus Quae in Montibus Uraliis Inveniuntur; AG Schadii: Berlin, Germany, 1839. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, H.L. Über die Cäsium- und Kalium-Bleihalogenide. Z. Für Anorg. Chem. 1893, 3, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Huang, Y.Y.; Du, W.Y.; Fan, Z.Y.; Chang, J.W.; Wang, H.; Jin, Y.P.; Xu, X.L. Nonlinear Optical Response on the Surface of Semiconductor SnS2 Probed by Terahertz Emission Spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 21559–21567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, S.F.; Wang, L.; Huang, Y.F.; Liu, H.Y.; Huang, J.W.; Dong, N.N.; Liu, W.M.; Kislyakov, I.M.; Nunzi, J.M.; et al. Direct observation of interlayer coherent acoustic phonon dynamics in bilayer and few-layer PtSe2. Photonics Res. 2019, 7, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.N.; Garcia de Arquer, F.P.; Sabatini, R.P.; Sargent, E.H. Perovskites for Light Emission. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1801996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, N.; Tan, L.; Li, M.; Zhou, J.; Ye, Y.; Jiao, B.; Ding, L.; Yi, C. 25%-Efficiency flexible perovskite solar cells via controllable growth of SnO2. iEnergy 2024, 3, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Zhao, D.; Yu, Y.; Shrestha, N.; Ghimire, K.; Grice, C.R.; Wang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Cimaroli, A.J.; Ellingson, R.J.; et al. Fabrication of Efficient Low-Bandgap Perovskite Solar Cells by Combining Formamidinium Tin Iodide with Methylammonium Lead Iodide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 12360–12363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Ji, H.; Li, X.; Wu, D.; Xu, T.; Chen, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Strategy of Solution-Processed All-Inorganic Heterostructure for Humidity/Temperature-Stable Perovskite Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 1462–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, X.Y.; Cortecchia, D.; Yin, J.; Bruno, A.; Soci, C. Lead iodide perovskite light-emitting field-effect transistor. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Shi, Y.; Hu, W.; Chiu, M.H.; Liu, Z.; Bera, A.; Li, F.; Wang, H.; Li, L.J.; Wu, T. Heterostructured WS2/CH3NH3PbI3 Photoconductors with Suppressed Dark Current and Enhanced Photodetectivity. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 3683–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; McEvoy, N.; Fan, P.; Blau, W.J. Layered PtSe2 for Sensing, Photonic, and (Opto-)Electronic Applications. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2004070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.C.; Yeh, H.; Wu, P.H.; Lin, C.C.; Li, C.S.; Yeh, T.T.; Chou, Y.; Wei, C.Y.; Wen, C.Y.; Chou, Y.C.; et al. Atomic-Layer Controlled Interfacial Band Engineering at Two-Dimensional Layered PtSe2/Si Heterojunctions for Efficient Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Production. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 4627–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.B.; Xu, W.Q.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S.F.; Zhang, W.J.; Suo, P.; Lin, X.; Wang, J.; Jin, Z.M.; Liu, W.M.; et al. Thickness-Dependent Ultrafast Photocarrier Dynamics in Selenizing Platinum Thin Films. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 10719–10726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemir, A.; Akbali, B.; Kahraman, Z.; Badalov, S.V.; Ozcan, M.; Iyikanat, F.; Sahin, H. Structural, electronic and phononic properties of PtSe2: From monolayer to bulk. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2018, 33, 085002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Cheng, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, H.; Li, D. Robust Interlayer Coupling in Two-Dimensional Perovskite/Monolayer Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Heterostructures. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 10258–10264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, D. Interlayer coupling in two-dimensional perovskite/monolayer transition metal dichalcogenide heterostructures. 2D Mater. 2025, 12, 033005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protesescu, L.; Yakunin, S.; Bodnarchuk, M.I.; Krieg, F.; Caputo, R.; Hendon, C.H.; Yang, R.X.; Walsh, A.; Kovalenko, M.V. Nanocrystals of Cesium Lead Halide Perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, and I): Novel Optoelectronic Materials Showing Bright Emission with Wide Color Gamut. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 3692–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Shao, G.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Xiang, W.; Liang, X. Ultrastability and color-tunability of CsPb(Br/I)3 nanocrystals in P-Si-Zn glass for white LEDs. Chem Commun. 2018, 54, 12302–12305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, B.R.; Hoogland, S.; Adachi, M.M.; Wong, C.T.; Sargent, E.H. Conformal organohalide perovskites enable lasing on spherical resonators. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 10947–10952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum, T.C.; Mathews, N.; Xing, G.; Lim, S.S.; Chong, W.K.; Giovanni, D.; Dewi, H.A. Spectral Features and Charge Dynamics of Lead Halide Perovskites: Origins and Interpretations. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Firsov, A.A. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, J.D.; Aharonovich, I.; Cassabois, G.; Edgar, J.H.; Gil, B.; Basov, D.N. Photonics with hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Mishchenko, A.; Carvalho, A.; Castro Neto, A.H. 2D materials and van der Waals heterostructures. Science 2016, 353, aac9439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geim, A.K.; van der Grigorieva, I.V. Waals heterostructures. Nature 2013, 499, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.X.; You, L.; Faraji, N.; Lin, C.H.; Xu, X.M.; He, J.H.; Seidel, J.; Wang, J.L.; Alshareef, H.N.; Wu, T. Single-Crystal Hybrid Perovskite Platelets on Graphene: A Mixed-Dimensional Van Der Waals Heterostructure with Strong Interface Coupling. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1909672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradac, C.; Xu, Z.Q.; Aharonovich, I. Quantum Energy and Charge Transfer at Two-Dimensional Interfaces. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Shang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, P.; Sui, X.; Qiu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Ultrafast Charge Transfer in Perovskite Nanowire/2D Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Heterostructures. Phys. Chem. Lett 2018, 9, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-H.; Jing, Q.; Xu, F.; Lu, Z.-D.; Lu, Y.-Q. High-sensitivity optical-fiber-compatible photodetector with an integrated CsPbBr3–graphene hybrid structure. Optica 2017, 4, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zu, Z.; Zang, Z.; Hu, Z.; Hu, W.; Yao, Z.; Chen, W.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Zhou, M. CsPbBr3/Reduced Graphene Oxide nanocomposites and their enhanced photoelectric detection application. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 245, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Yang, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, B.; Qiu, J. Efficient and Fast Inter-Layer Charge Transfer in a Quasi-2D PEPI/NiPS3 Heterojunction. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025, e01455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, S.; Zhou, Z.; Song, J.; Jiao, Z.; Ma, S.; Jia, G.; Jiang, Y. Carrier transfer in 2D perovskite/WSe2 monolayer heterostructure. J. Lumin. 2025, 286, 121451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpetzoglou, E.; Konidakis, I.; Kakavelakis, G.; Maksudov, T.; Kymakis, E.; Stratakis, E. Improved carrier transport in perovskite solar cells probed by femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 43910–43919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bao, D.; Deng, X.; Zhang, S.; Yu-Chun, L.; Ke, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z. Emerging probing perspective of two-dimensional materials physics: Terahertz emission spectroscopy. Light 2024, 13, 146. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Q.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, C. Characterization of Intrinsic Charge Carrier Dynamics in Lead Halide Perovskite Films Using Time-Resolved Terahertz Spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 10520–10527. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Hu, H.; Haselsberger, R.; Marcus, R.A.; Michel-Beyerle, M.-E.; Lam, Y.M.; Zhu, J.-X.; La-O-Vorakiat, C.; Beard, M.C.; Chia, E.E. Monitoring electron–phonon interactions in lead halide perovskites using time-resolved THz spectroscopy. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 8826–8835. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quan, C.; Xing, X.; Jia, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Huang, S.; Liu, Z.; Du, J.; Leng, Y. Hot Carrier Transfer in PtSe2/Graphene Enabled by the Hot Phonon Bottleneck. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 9456–9463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, M.B.; Herz, L.M. Hybrid Perovskites for Photovoltaics: Charge-Carrier Recombination, Diffusion, and Radiative Efficiencies. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wang, X.; Hautzinger, M.P.; Pan, D.; Dang, L.; Wright, J.C.; Pan, A.; Jin, S. Multicolor heterostructures of two-dimensional layered halide perovskites that show interlayer energy transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 15675–15683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munson, K.T.; Grieco, C.; Kennehan, E.R.; Stewart, R.J.; Asbury, J.B. Time-resolved infrared spectroscopy directly probes free and trapped carriers in organo-halide perovskites. ACS Energy Lett 2017, 2, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Xue, J.; Fu, H.B. Tunable Halide Perovskites for Miniaturized Solid-State Laser Applications. Adv. Opt. Mater 2019, 7, 1900099. [Google Scholar]

- Nedelcu, G.; Protesescu, L.; Yakunin, S.; Bodnarchuk, M.I.; Grotevent, M.J.; Kovalenko, M.V. Fast Anion-Exchange in Highly Luminescent Nanocrystals of Cesium Lead Halide Perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, I). Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 5635–5640. [Google Scholar]

- Bellus, M.Z.; Li, M.; Lane, S.D.; Ceballos, F.; Cui, Q.; Zeng, X.C.; Zhao, H. Type-I van der Waals heterostructure formed by MoS2 and ReS2 monolayers. Nanoscale Horiz. 2017, 2, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Ma, J.; Li, D. Two-Dimensional Hybrid Perovskite-Based van der Waals Heterostructures. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 8178–8187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, C.J.; Lu, C.H.; He, C.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.Y.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Xu, X.L. Band Alignment of MoTe2/MoS2 Nanocomposite Films for Enhanced Nonlinear Optical Performance. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6, 1801733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ostrowski, D.P.; France, R.M.; Zhu, K.; Van De Lagemaat, J.; Luther, J.M.; Beard, M.C. Observation of a hot-phonon bottleneck in lead-iodide perovskites. Nat. Photonics 2016, 10, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wu, B.; Wu, H.; Shi, Y.; Wu, K.; Wang, Y. Hot phonon bottleneck stimulates giant optical gain in lead halide perovskite quantum dots. ACS Photonics 2022, 9, 457–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.X.; Zhang, X.; Das, S.; Kioupakis, E.; Van de Walle, C.G. Unexpectedly strong Auger recombination in halide perovskites. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1801027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Cui, M.; Li, S.; Sun, C.; Huang, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhang, L.; Lv, M.; Qin, C.; Liu, Y. Reducing the impact of Auger recombination in quasi-2D perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhumekenov, A.A.; Saidaminov, M.I.; Haque, M.A.; Alarousu, E.; Sarmah, S.P.; Murali, B.; Dursun, I.; Miao, X.-H.; Abdelhady, A.L.; Wu, T. Formamidinium lead halide perovskite crystals with unprecedented long carrier dynamics and diffusion length. ACS Energy Lett. 2016, 1, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhyaksa, G.W.; Veldhuizen, L.W.; Kuang, Y.; Brittman, S.; Schropp, R.E.; Garnett, E.C. Carrier diffusion lengths in hybrid perovskites: Processing, composition, aging, and surface passivation effects. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 5259–5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Li, X.; Tsai, H.; Hou, C.-H.; Huang, H.-H.; Ghosh, D.; Shyue, J.-J.; Wang, L.; Tretiak, S.; Ma, X. Long carrier diffusion length in two-dimensional lead halide perovskite single crystals. Chem 2022, 8, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, M.; Moore, D.T.; Yan, Y.; Miller, E.M.; Zhu, K.; Beard, M.C. Top and bottom surfaces limit carrier lifetime in lead iodide perovskite films. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 16207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, G.; Mathews, N.; Sun, S.; Lim, S.S.; Lam, Y.M.; Gratzel, M.; Mhaisalkar, S.; Sum, T.C. Long-range balanced electron- and hole-transport lengths in organic-inorganic CH3NH3PbI3. Science 2013, 342, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Liao, L.P.; Elseman, A.M.; Yao, Y.Q.; Lin, C.Y.; Hu, W.; Liu, D.B.; Xu, C.Y.; Zhou, G.D.; Li, P.; et al. An internally photoemitted hot carrier solar cell based on organic-inorganic perovskite. Nano Energy 2020, 68, 104383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, D.; Casalenuovo, K.; Takeda, Y.; Conibeer, G.; Guillemoles, J.-F.; Patterson, R.; Huang, L.; Green, M. Hot carrier solar cells: Principles, materials and design. Physica E 2010, 42, 2862–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I.C.; Hoke, E.T.; Solis-Ibarra, D.; McGehee, M.D.; Karunadasa, H.I. A layered hybrid perovskite solar-cell absorber with enhanced moisture stability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11232–11235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, L.; Taheri, B.; Martin-Garcia, B.; Bellani, S.; Di Girolamo, D.; Agresti, A.; Oropesa-Nunez, R.; Pescetelli, S.; Vesce, L.; Calabro, E.; et al. MoS2 Quantum Dot/Graphene Hybrids for Advanced Interface Engineering of a CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Solar Cell with an Efficiency of over 20%. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 10736–10754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Zhang, Y.P.; Lu, Y.; Xu, W.D.; Mu, H.R.; Chen, C.Y.; Qiao, H.; Song, J.C.; Li, S.J.; Sun, B.Q.; et al. Hybrid Graphene-Perovskite Phototransistors with Ultrahigh Responsivity and Gain. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2015, 3, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.J.; Guo, R.; Zeng, H.P.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.Y.; You, S.; Li, M.; Luo, L.; Lira-Cantu, M.; Li, L.; et al. Improved performance and stability of perovskite solar modules by interface modulating with graphene oxide crosslinked CsPbBr3 quantum dots. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Wang, W.; Song, J.; Jiao, Z.; Ma, S.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, J.; Jia, G.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, Z. Carrier transfer in quasi-2D perovskite/MoS2 monolayer heterostructure. Nanophotonics 2023, 12, 4495–4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, D.; Ge, C.; He, M.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Pan, A. Enhancing circular polarization of photoluminescence of two-dimensional Ruddlesden–Popper perovskites by constructing van der Waals heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 119, 151101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Wen, X.; Huang, S.; Sheng, R.; Harada, T.; Kee, T.W.; Green, M.; Ho-Baillie, A. Ultrafast Carrier Dynamics in Methylammonium Lead Bromide Perovskite. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 2542–2547. [Google Scholar]

- Dursun, I.; Maity, P.; Yin, J.; Turedi, B.; Zhumekenov, A.A.; Lee, K.J.; Mohammed, O.F.; Bakr, O.M. Why are Hot Holes Easier to Extract than Hot Electrons from Methylammonium Lead Iodide Perovskite? Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1900084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, M.; Tomioka, T.; Ashida, M.; Hoyano, M.; Akashi, R.; Yamada, Y.; Aharen, T.; Kanemitsu, Y. Longitudinal Optical Phonons Modified by Organic Molecular Cation Motions in Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Perovskites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 145506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mante, P.A.; Stoumpos, C.C.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; Yartsev, A. Electron-acoustic phonon coupling in single crystal CH3NH3PbI3 perovskites revealed by coherent acoustic phonons. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Wei, Q.; Cai, Y.Q.; Liu, T.H.; Wu, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.H.; Xia, Y.D.; Xing, G.C.; Huang, W. Crystal face dependent charge carrier extraction in TiO2/perovskite heterojunctions. Nano Energy 2020, 67, 104227. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, J.-F.; Xu, Y.-F.; Wang, X.-D.; Chen, H.-Y.; Kuang, D.-B. CsPbBr3 Nanocrystal/MO2 (M = Si, Ti, Sn) Composites: Insight into Charge-Carrier Dynamics and Photoelectrochemical Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 42301–42309. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Lopez, J.; Puscher, B.M.D.; Guldi, D.M.; Palomares, E. Improved Carrier Collection and Hot Electron Extraction Across Perovskite, C60, and TiO2 Interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 1236–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Kohnehpoushi, S.; Nazari, P.; Nejand, B.A.; Eskandari, M. MoS2: A two-dimensional hole-transporting material for high-efficiency, low-cost perovskite solar cells. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 205201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grill, I.; Aygüler, M.F.; Bein, T.; Docampo, P.; Hartmann, N.F.; Handloser, M.; Hartschuh, A. Charge Transport Limitations in Perovskite Solar Cells: The Effect of Charge Extraction Layers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 37655–37661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, J.J.; van de Lagemaat, J.; Al-Jassim, M.M.; Kurtz, S.; Yan, Y.F.; Zhu, K. Perovskite Photovoltaics: The Path to a Printable Terawatt-Scale Technology. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 2540–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellani, S.; Najafi, L.; Martín-García, B.; Ansaldo, A.; Castillo, A.E.D.; Prato, M.; Moreels, I.; Bonaccorso, F. Graphene-Based Hole-Selective Layers for High-Efficiency, Solution Processed, Large-Area, Flexible, Hydrogen-Evolving Organic Photocathodes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 21887–21903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, A.; Gemming, S.; Seifert, G.; Tománek, D. Chemical and Electronic Repair Mechanism of Defects in MoS2 Monolayers. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 9989–9996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.C.; Zhang, S.S.; Li, L.B.; Chen, W. Research progress on large-area perovskite thin films and solar modules. J. Mater. 2017, 3, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, H.; Song, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Hu, Z.; Zou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. Spontaneous 2D perovskite formation at the buried interface of perovskite solar cells enhances crystallization uniformity and defect passivation. Nat. Photonics 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, E.; Kim, K.S.; Yeom, G.Y.; Nalwa, H.S. Atomically Thin-Layered Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS2) for Bulk-Heterojunction Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 3223–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, C.L.; Lei, H.W.; Zheng, X.L.; Qin, P.L.; Xiong, L.B.; Zhao, X.Z.; Yan, Y.F.; Fang, G.J. Interface engineering in planar perovskite solar cells: Energy level alignment, perovskite morphology control and high performance achievement. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 1658–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slayney, A.H.; Smaha, R.W.; Smith, I.C.; Jaffe, A.; Umeyama, D.; Karunadasa, H.I. Chemical Approaches to Addressing the Instability and Toxicity of Lead-Halide Perovskite Absorbers. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Li, W.; Cui, Z.; Li, Y.; He, W.; Fu, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Fang, J. ITO Nanoparticles to Stabilize the Self-Assembly of Hole Transport Layer in Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2025, 7, e17573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Shen, Z.; Shen, Y.; Yan, G.; Wang, Y.; Han, Q.; Han, L. Reinforcing self-assembly of hole transport molecules for stable inverted perovskite solar cells. Science 2024, 383, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Weiss, N.O.; Duan, X.; Cheng, H.-C.; Huang, Y.; Duan, X. Van der Waals heterostructures and devices. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, Q.; Gan, L.; Li, H.; Xiong, J.; Zhai, T. Booming Development of Group IV-VI Semiconductors: Fresh Blood of 2D Family. Adv. Sci. 2016, 3, 1600177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.K.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Park, M.H.; Jeong, S.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Kwon, S.J.; Han, T.H.; Yoo, S.; Lee, T.W. Efficient Flexible Organic/Inorganic Hybrid Perovskite Light-Emitting Diodes Based on Graphene Anode. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kwon, J.; Hwang, E.; Ra, C.-H.; Yoo, W.J.; Ahn, J.-H.; Park, J.H.; Cho, J.H. High-performance perovskite-graphene hybrid photodetector. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Li, K.; Zhu, J.; Xu, H.; Ali, N.; Rahimi-Iman, A.; Wu, H. A new strategy to improve the performance of MoS2-based 2D photodetector by synergism of colloidal CuInS2 quantum dots and surface plasma resonance of noble metal nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 856, 158179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, B.S.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhang, Z.H.; Lian, Z.D.; Zheng, Z.Y.; Wei, Z.P.; Li, L.; Ng, K.W.; Wang, S.P.; Liu, Z.B. Photosensitive Dielectric 2D Perovskite Based Photodetector for Dual Wavelength Demultiplexing. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2300632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.X.; Long-Hui, Z.; Tong, X.W.; Gao, Y.; Xie, C.; Tsang, Y.H.; Luo, L.B.; Wu, Y.C. Ultrafast, Self-Driven, and Air-Stable Photodetectors Based on Multilayer PtSe2/Perovskite Heterojunctions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Wan, Y.; Li, H.; Fang, S.; Huang, F.; Zhou, B.; Jiang, K.; Tung, V.; Li, L.-J.; Shi, Y. Two-Dimensional Cs2AgBiBr6/WS2 Heterostructure-Based Photodetector with Boosted Detectivity via Interfacial Engineering. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 3985–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Wu, W.; Zhu, M.; Shen, X.; Yin, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H.; Lu, H. CVD growth of perovskite/graphene films for high-performance flexible image sensor. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Fang, H.; Lian, Z.; Lv, Q.; Sun, J.-L.; Yan, Q. High-performance stretchable photodetector based on CH3NH3PbI3 microwires and graphene. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 10538–10544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Carvalho, A.; Liu, H.; Lim, S.X.; Castro Neto, A.H.; Sow, C.H. Hybrid bilayer WSe2–CH3NH3PbI3 organolead halide perovskite as a high-performance photodetector. Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 12124–12128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fullon, R.; Acerce, M.; Petoukhoff, C.E.; Yang, J.; Chen, C.; Du, S.; Lai, S.K.; Lau, S.P.; Voiry, D. Solution-processed MoS2/organolead trihalide perovskite photodetectors. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1603995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- veeramalai Chandrasekar, P.; Yang, S.; Hu, J.; Sulaman, M.; Saleem, M.I.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zou, B. A one-step method to synthesize CH3NH3PbI3: MoS2 nanohybrids for high-performance solution-processed photodetectors in the visible region. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 085707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, F.; Zhu, Z.; Dai, J.; Gao, K.; Wei, Q.; Shi, X.; Sun, Q.; Yan, Y.; Li, H. Unconventional solution-phase epitaxial growth of organic-inorganic hybrid perovskite nanocrystals on metal sulfide nanosheets. Sci. China Mater. 2019, 62, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Jeong, S.-H.; Park, M.-H.; Kim, Y.-H.; Wolf, C.; Lee, C.-L.; Heo, J.H.; Sadhanala, A.; Myoung, N.; Yoo, S. Overcoming the electroluminescence efficiency limitations of perovskite light-emitting diodes. Science 2015, 350, 1222–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, A.; Mitioglu, A.; Plochocka, P.; Portugall, O.; Wang, J.T.-W.; Stranks, S.D.; Snaith, H.J.; Nicholas, R.J. Direct measurement of the exciton binding energy and effective masses for charge carriers in organic–inorganic tri-halide perovskites. Nat. Phys. 2015, 11, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.-S.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Y.-K.; Liao, L.-S. Hybrid-Dimensional Heterostructure Enables Efficient Near-Infrared Perovskite Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 25930–25938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ou, Q.; Ha, S.T.; Qiu, C.W.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, Y.B.; Xiong, Q.; Bao, Q. Photonics and Optoelectronics of 2D Metal-Halide Perovskites. Small 2018, 14, e1800682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Xu, L.; Dong, Y.; Zeng, H. Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes Based on Inorganic Perovskite Cesium Lead Halides (CsPbX3). Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 7162–7167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Cheng, L.; Ge, R.; Zhang, S.; Miao, Y.; Zou, W.; Yi, C.; Sun, Y.; Cao, Y.; Yang, R. Perovskite light-emitting diodes based on solution-processed self-organized multiple quantum wells. Nat. Photonics 2016, 10, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.C.; Wang, G.; Li, D.; He, Q.; Yin, A.; Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Ding, M.; Huang, Y.; Duan, X. van der Waals Heterojunction Devices Based on Organohalide Perovskites and Two-Dimensional Materials. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Ryoo, S.; Kim, J.S.; Jang, J.; Ahn, H.; Kim, D.; Jung, J.; Kong, T.; Choi, H.; Lee, Y.S.; et al. Enhanced Photodetection Performance of an In Situ Core/Shell Perovskite-MoS2 Phototransistor. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 16905–16913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Huang, W.; Pattanasattayavong, P.; Lim, J.; Li, R.; Sakai, N.; Panidi, J.; Hong, M.J.; Ma, C.; Wei, N.; et al. Deciphering photocarrier dynamics for tuneable high-performance perovskite-organic semiconductor heterojunction phototransistors. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Heterostructure Type | R [A W−1] | EQE/[%] | D* [Jones] | On/Off Ratio | Response Time [ms] | Test Conditions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAPbI3 film /graphene | 180 | ≈5 × 104% | ≈109 | / | trise: 87, tdecay: 540 | λ: 520 nm, P: 1 mW, | [84] |

| MAPbI3 film /graphene | ≈2700 | / | / | / | trise: <50, tdecay: <50 | λ: 633 nm, P: 1 pW, Vbias: 0.1 V | [89] |

| MAPbI3 microwire /graphene | 2.2 × 10−3 | / | 1.78 × 105 | / | trise: ≈68 | λ: 375–785 nm, P: 13.5 mW cm−2, Vbias: 0.01 V | [90] |

| MAPbI3 film/WS2 | 17 | / | 2 × 1012 | 3 × 105 | trise: 2.7, tdecay: 7.5 | For R: λ: white light, P: 0.2 μW cm−2, Vbias: 5 V For D*: λ: 505 nm, P: 0.5 mW cm−2, Vbias: 5 V | [10] |

| MAPbI3 film/WSe2 | 110 | 2.5 × 104% | 2.2 × 1011 | / | trise1: 143, trise2: 2113; tdecay1: 225, tdecay2: 2983 | λ: 532 nm, P: 2.8 mW, Vbias: 2 V | [91] |

| MAPbI3 film /2H-MoS2 | 142 | 3.5 × 104% | / | ≈300 | trise: <25, tdecay: <50 | λ: 500 nm, P: 31.3 μW cm−2, Vbias: 2 V | [92] |

| MAPbI3 NC /MoS2 | 0.696 | / | 1.94 × 10−12 | 87.47 | trise: 50 (from 10 to 90%), tdecay: 16 (from 90 to 10%) | λ: 532 nm, P: 51.5 μW cm−2, Vbias: 3 V | [93] |

| MAPbBr3 NC /MoS2 | 5.6 × 10−3 | / | / | 1.41 | trise: 1650 (80%), tdecay: 1200 (80%) | λ: 405 nm, P: 9.6 mW, Vbias: 3 V | [94] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quan, C.; Yan, J.; Liu, X.; Lin, Q.; Xu, B.; Qiu, J. Progress in Charge Transfer in 2D Metal Halide Perovskite Heterojunctions: A Review. Materials 2025, 18, 5690. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245690

Quan C, Yan J, Liu X, Lin Q, Xu B, Qiu J. Progress in Charge Transfer in 2D Metal Halide Perovskite Heterojunctions: A Review. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5690. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245690

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuan, Chenjing, Jiahe Yan, Xiaofeng Liu, Qing Lin, Beibei Xu, and Jianrong Qiu. 2025. "Progress in Charge Transfer in 2D Metal Halide Perovskite Heterojunctions: A Review" Materials 18, no. 24: 5690. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245690

APA StyleQuan, C., Yan, J., Liu, X., Lin, Q., Xu, B., & Qiu, J. (2025). Progress in Charge Transfer in 2D Metal Halide Perovskite Heterojunctions: A Review. Materials, 18(24), 5690. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245690