Effect of Laser Shock Peening Times on Low-Cycle Fatigue Properties and Fracture Mechanism of Additive TA15 Titanium Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Preparation Processes

2.2. Preparation of Test Samples

2.3. Experimental Procedures

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of LSP Count on Fatigue Life

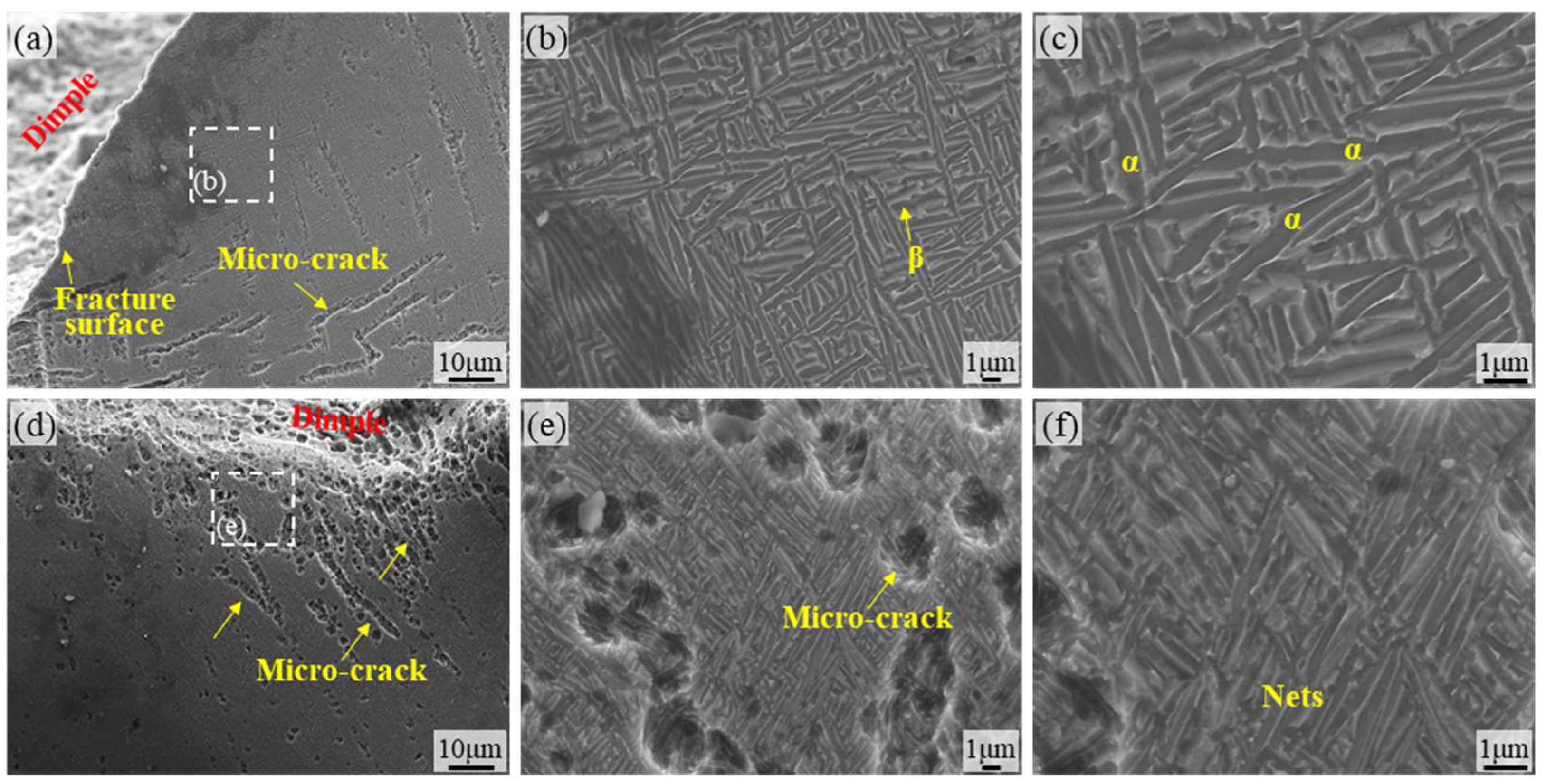

3.2. Fatigue Fracture Toughness Analysis and Fracture Mechanism

3.3. Effect of LSP Frequency on the Surface Integrity of TA15

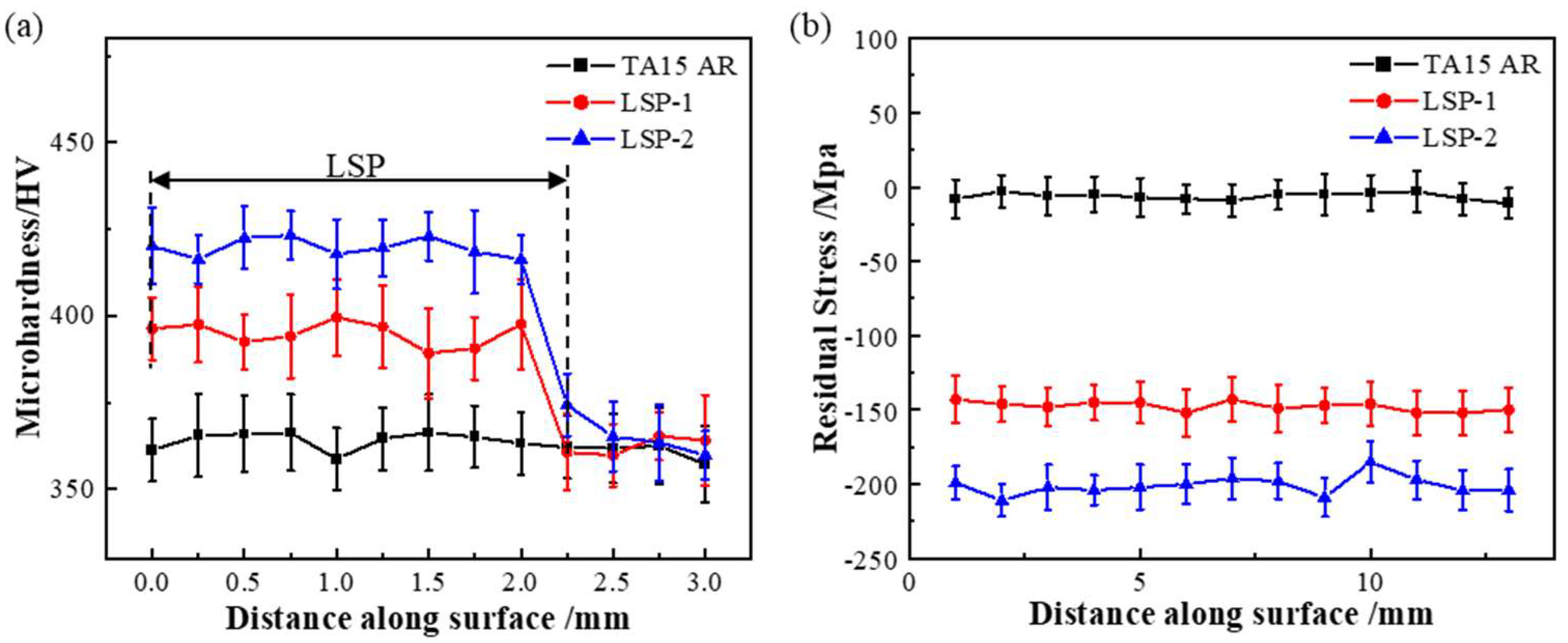

3.4. Hardness and Residual Stress Test Results

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- LSP treatment significantly enhances the fatigue life of the material. The fatigue life of the single-stage strengthened (TA15 LSP-1) specimen reached 170,400 cycles, which is 2.34 times that of the TA15 AR specimen. The fatigue life of the double-stage strengthened (TA15 LSP-2) specimen further increased to 2.56 times that of the AR specimen, indicating that the strengthening effect is cumulative.

- (2)

- LSP promotes the migration of fatigue crack initiation from the surface to the subsurface, improves crack propagation behavior, results in finer and more uniform fatigue striations, reduces secondary cracking, and effectively delays the crack growth rate.

- (3)

- LSP optimized the fracture mechanism by preserving the dimple characteristics in the final fracture zone while reducing the proportion of intergranular fracture. The fracture surface morphology of TA15 LSP-2 specimens exhibited a smoother profile, further enhancing fracture resistance.

- (4)

- With increasing LSP cycles, the surface microstructure becomes finer. Specimens treated with TA15 LSP-2 exhibit a coexisting microstructure of lamellar α and acicular martensite, demonstrating significant grain refinement that forms the microscopic basis for improved fatigue performance.

- (5)

- Mechanical property testing indicates that LSP treatment significantly enhances surface material properties by inducing plastic deformation in the surface layer. With increasing LSP cycles, surface microhardness rose from 360 HV in the untreated state to 390.6 HV (TA15 LSP-1, an 8.51% increase) and 412.3 HV (TA15 LSP-2, a 14.53% increase), while surface residual compressive stresses reached -145 MPa and -183 MPa, respectively. This synergistic effect of surface hardening and compressive stress effectively suppresses fatigue crack initiation and propagation, constituting a key mechanism by which LSP enhances the fatigue performance of TA15 titanium alloy.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Z.; He, B.; Lyu, T.; Zou, Y. A Review on Additive Manufacturing of Titanium Alloys for Aerospace Applications: Directed Energy Deposition and Beyond Ti-6Al-4V. J. Miner. Met. Mater. Soc. 2021, 73, 1804–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Geng, X.; Liu, H.; Guo, D.; Lu, X.; Zheng, D.; Xu, Y.; Guan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Du, B. Effect of heat treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of electron-beam powder bed fused TiB w/TA15 composite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2026, 950, 149533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L. Effect of laser offset on microstructure and mechanical properties of Nb521/TA15 dissimilar joints. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 38, 5953–5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yan, S.; Qu, S.; Yi, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, T.; Xu, C. Microstructure of titanium alloy in additive/subtractive hybrid manufacturing: A review. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1014, 178769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.M.; Yang, Y.; Tan, Y.B.; Xiang, S.; Zhao, F.; Ji, X.M.; Huang, G. Synergistically enhancing the strength and ductility of TA15 titanium alloy through hot rolling and short-time annealing. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1038, 182796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Shen, D.; Wang, Q.; Su, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Xiong, R.; Meng, Y.; Feng, Z.; Hao, S.; et al. Microstructure control and high-temperature mechanical response of TA15 titanium alloy fabricated by selective laser melting. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 49, 114072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, R.S.; Jhavar, S. Ti based alloys for aerospace and biomedical applications fabricated through wire + arc additive manufacturing (WAAM). Mater. Today Proc. 2024, 98, 226–232. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Shin, Y.C. Additive manufacturing of Ti6Al4V alloy: A review. Mater. Des. 2019, 164, 107552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnala, D.C.; Hanning, F.; Joshi, S.; Andersson, J. The parametric investigation and microstructural characterization of laser directed energy deposited NiCrAlY powder. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 948–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, B.; Yin, J.; Wang, B.; Lu, Y.; Zhan, W.; Huang, K.; Han, B.; He, B.; Zhang, Q. Microstructure evolution and performance improvement of 42CrMo steel repaired by an ultrasonic rolling assisted laser directed energy deposition IN718 superalloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1026, 180385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Chen, Y.; Jia, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, S.; Yin, L. Microstructure and mechanical properties of dissimilar NiTi/Ti6Al4V joints via back-heating assisted friction stir welding. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 64, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Kong, D.; Ma, R.; Liu, L.; Li, P. Microstructure evolution of 2205 duplex stainless steel (DSS) and inconel 718 dissimilar welded joints and impact on corrosion and mechanical behavior. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 929, 148136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, X. A novel fatigue life prediction method for the laser deposition repaired TA15 component with annealing heat treatment. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 177, 109649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.F.; Qu, C.X.; Duan, C.F.; Li, F.L.; Li, X.Q.; Qu, S.G. Explore the nature of gradient deformation layer constructed by high-density electric pulse assisted ultrasonic nanocrystalline surface modification for Ti6Al4V alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wu, H.; Wu, C.L.; Zhang, C.H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, D. A hybrid laser surface modification technique: Microstructural and property regulation mechanisms of titanium alloy via laser shock forging. Mater. Charact. 2025, 229, 115562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.; Ramulu, M. Fatigue performance evaluation of selective laser melted Ti-6Al-4V. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 598, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; He, X.; Wu, B.; Dang, L.; Xin, H.; Li, Y. A fatigue life prediction approach for porosity defect-induced failures in directed energy deposited Ti-6Al-4V considering crack growth environment. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 184, 108272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.B.; Cui, X.L.; Yu, M.R.; Jiang, G.R.; Liu, F.Q.; Yang, X.Y.; Chen, J. Microstructure evolution and strengthening mechanisms of laser directed energy deposited TA15 titanium alloy with synchronous ultrasonic impact. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1037, 182407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Tang, W.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, C. Studies on surface integrity and fatigue performance of Ti-17 alloy induced by ultrasonic surface rolling process. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 512, 132336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warzanskyj, W.; Angulo, I.; Cordovilla, F.; Díaz, M.; Porro, J.A.; García-Beltrán, A.; Cabeza, S.; Ocaña, J. Analysis of the thermal stability of residual stresses induced in Ti-6Al-4 V by high density LSP treatments. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 931, 167530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadalupe, M.; Bravo, A.; Gomez-rosas, G.; Morales, M.; Munoz-martin, D.; Moreno-labella, J.J.; Lopez, J.M.L.; Galvan, J.G.Q.; Rubio-Gonzalez, C.; Rodriguez, F.J.C.; et al. Effects of Laser Shock Processing on the Mechanical Properties of 6061-T6 Aluminium Alloy Using Nanosecond and Picosecond Laser Pulses. Materials 2025, 18, 4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Shen, Y.; Dong, Z.; Xu, H. Ultrasonic surface rolling process for improving fatigue crack propagation resistance of laser-clad TC4-TA15 titanium alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2026, 520, 132974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Huang, J.; Yang, G.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, S.; An, D. Effects of ultrasonic shot peening on fatigue behavior of TA15 titanium alloy fabricated by laser melting deposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 446, 128769. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Chattopadhyay, K.; Singh, V. Optimization of the Duration of Ultrasonic Shot Peening for Enhancement of Fatigue Life of the Alloy Ti-6Al-4V. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Zhu, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Hao, Q.; Guo, B.; Zhong, F.; Chen, W.; et al. Study on the Effect of Laser Shock Angle on Surface Integrity and Wear Performance of H13 Steel. Lubricants 2025, 13, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Shen, Y.; Hua, Z.; Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. Improving the corrosion resistance and wear resistance of Carbon Steel by laser shock peening and shot peening. Tribol. Int. 2025, 214, 111374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Zheng, F.; Lin, J.; Ren, Z.; Lin, Y. Utilization of red mud as copper substitute in eco-friendly resin-based brake composites: Performance evaluation and machine learning prediction. Tribol. Int. 2025, 214, 111324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, L.; Li, L.; Deng, W.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Xu, G.; Liu, L.; Li, P. Obvious corrosion resistance of 2Cr13 martensitic stainless steel subjected to thermo-mechanical laser shock peening and subsequent slight polishing. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 39, 103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Liu, C.; Li, K.; Feng, J.; Qiao, R.; Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Chang, T.; Huang, K.; Lu, B. Improved properties of wire-arc directed energy deposited Al—Mg alloy through laser shock peening. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 1653–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kljestan, N.; Balos, S.; Pecanac, M.; McWilliams, B.A.; Knezevic, M. Effects of laser shock peening on fatigue performance of an ultrahigh-strength low-alloy steel fabricated via laser powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 3752–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep Kumar, S.; Radhika, N.; Dinesh Babu, P.; Ram Prabhu, T.; Gautam, J.; Chakkravarthy, V. Evaluation of high-temperature wear behaviour of selective laser melted 17-4 PH stainless steel through laser shock peening. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 5265–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Sha, Y.; Hou, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, F.; Li, X. Effect of Laser Shock Peening on High-Cycle Fatigue Performance and Residual Stress in DH36 Welded Joints. Materials 2025, 18, 5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricín, D.; Jansa, Z.; Kaufman, J.; Špirit, Z.; Fulín, Z.; Strejcius, J. Effect of laser shock peening on the microstructure of GX4CrNi13–4 martensitic stainless steel. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 149, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, N.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Yang, J.; Liu, D. Surface nanocrystallization of body-centered cubic beta phase in Ti–6Al–4V alloy subjected to ultrasonic surface rolling process. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 361, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Hayama, M.; Kikuchi, S.; Komotori, J. Peening methods for AISI 4140 steel to induce stable compressive residual stress against cyclic axial loading. Int. J. Fatigue 2025, 201, 109200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Cao, S.; Liu, C. Hybrid treatment of shot peening and vibratory finishing for fatigue enhancement in laser powder bed fused 304L steel. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 2025, 344, 119010. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Chen, C.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y. Effect of laser shock peening on residual stress of 316L stainless steel laser metal deposition part. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 3988–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Process Parameters | Parameter Value |

|---|---|

| Scanning speed (mm/s) | 10 |

| Laser power (W) | 2400 |

| Laser spot diameter (mm) | 4 |

| Overlap ratio (%) | 50 |

| Interlayer height (mm) | 0.6 |

| Protective gas (L/min) | 15 |

| Types of shielding gases | Ar |

| Component (wt.%) | Fe | C | Al | V | Zr | Mo | Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA15 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.10 | 5.5–7.1 | 1.8–3.7 | 1.5–2.5 | 0.5–2.0 | Bal. |

| Material | Tensile Strength /MPa | Yield Strength /MPa | Elongation /% | Elasticity Modulus E/GPa | Density /(kg·m−3) | Poisson’s Ratio υ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA15 | 902.04 | 434.52 | 8.50 | 115.79 | 4.45 | 0.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pei, X.; Wang, S.; Xu, Z.; Gu, Z.; Peng, Y.; Li, P. Effect of Laser Shock Peening Times on Low-Cycle Fatigue Properties and Fracture Mechanism of Additive TA15 Titanium Alloy. Materials 2025, 18, 5670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245670

Pei X, Wang S, Xu Z, Gu Z, Peng Y, Li P. Effect of Laser Shock Peening Times on Low-Cycle Fatigue Properties and Fracture Mechanism of Additive TA15 Titanium Alloy. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245670

Chicago/Turabian StylePei, Xu, Sailan Wang, Zhaomei Xu, Zhouzhi Gu, Yuchun Peng, and Pengfei Li. 2025. "Effect of Laser Shock Peening Times on Low-Cycle Fatigue Properties and Fracture Mechanism of Additive TA15 Titanium Alloy" Materials 18, no. 24: 5670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245670

APA StylePei, X., Wang, S., Xu, Z., Gu, Z., Peng, Y., & Li, P. (2025). Effect of Laser Shock Peening Times on Low-Cycle Fatigue Properties and Fracture Mechanism of Additive TA15 Titanium Alloy. Materials, 18(24), 5670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245670