Evolution of Cluster Morphology and Its Impact on Dislocation Behavior in a Strip-Cast HSLA Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shrestha, S.L.; Xie, K.Y.; Zhu, C.; Ringer, S.P.; Killmore, C.; Carpenter, K.; Kaul, H.; Williams, J.G.; Cairney, J.M. Cluster strengthening of Nb-microalloyed ultra-thin cast strip steels produced by the CASTRIP® process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 568, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.Y.; Yao, L.; Zhu, C.; Cairney, J.M.; Killmore, C.R.; Barbaro, F.J.; Williams, J.G.; Ringer, S.P. Effect of Nb microalloying and hot rolling on microstructure and properties of ultrathin cast strip steels produced by the CASTRIP® process. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2011, 42, 2199–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felfer, P.J.; Killmore, C.R.; Williams, J.G.; Carpenter, K.R.; Ringer, S.P.; Cairney, J.M. A quantitative atom probe study of the Nb excess at prior austenite grain boundaries in a Nb microalloyed strip-cast steel. Acta Mater. 2012, 60, 5049–5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Isac, M.; Guthrie, R.I.L. Progress in Strip Casting Technologies for Steel; Technical Developments. ISIJ Int. 2013, 53, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Marceau, R.K.W.; Guan, B.; Dorin, T.; Wood, K.; Hodgson, P.D.; Stanford, N. The effect of molybdenum on clustering and precipitation behaviour of strip-cast steels containing niobium. Materialia 2019, 8, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charleux, M.; Poole, W.J.; Militzer, M.; Deschamps, A. Precipitation behavior and its effect on strengthening of an HSLA-Nb/Ti steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2001, 32, 1635–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.C.M.; Pereloma, E.V.; Santos, D.B. Mechanical properities of an HSLA bainitic steel subjected to controlled rolling with accelerated cooling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2000, 283, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, Y.; Liao, T.; Wang, S.; Lv, B.; Guo, H.; Huang, Y.; Yong, Q.; Mao, X. Revealing the precipitation kinetics and strengthening mechanisms of a 450 MPa grade Nb-bearing HSLA steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 884, 145506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Casillas, G.; Wexler, D.; Killmore, C.; Pereloma, E. Application of advanced experimental techniques to elucidate the strengthening mechanisms operating in microalloyed ferritic steels with interphase precipitation. Acta Mater. 2020, 201, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Miyamoto, G.; Shinbo, K.; Furuhara, T.; Ohmura, T.; Suzuki, T. Tsuzaki Effects of transformation temperature on VC interphase precipitation and resultant hardness in low-carbon steels. Acta Mater. 2015, 84, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Weyland, M.; Bikmukhametov, I.; Miller, M.K.; Hodgson, P.D.; Timokhina, I. Transformation from cluster to nano-precipitate in microalloyed ferritic steel. Scr. Mater. 2019, 160, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Timokhina, I.; Pereloma, E. Clustering, nano-scale precipitation and strengthening of steels. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 118, 100764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Timokhina, I.; Zhu, C.; Ringer, S.P.; Hodgson, P.D. Clustering and precipitation processes in a ferritic titanium-molybdenum microalloyed steel. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 690, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhara, S.; Marceau, R.K.W.; Wood, K.; Dorin, T.; Timokhina, I.B.; Hodgson, P.D. Precipitation and clustering in a Ti-Mo steel investigated using atom probe tomography and small-angle neutron scattering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 718, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, F.; Ma, K.; Duan, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, P.; Liang, M.; Li, J. Novel AlCu solute cluster precipitates in the Al–Cu alloy by elevated aging and the effect on the tensile properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 862, 144454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.Y.; Zheng, T.; Cairney, J.M.; Kaul, H.; Williams, J.G.; Barbaro, F.J.; Killmore, C.R.; Ringer, S.P. Strengthening from Nb-rich clusters in a Nb-microalloyed steel. Scr. Mater. 2012, 66, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, S.; Li, S.; Cao, R.; Wu, H.; Wu, G.; Gao, J.; Feng, Q.; Li, H.; Mao, X. Achieving high strength and large elongation in a strip casting microalloyed steel by ageing treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 860, 144217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, S.; Li, X.; Gao, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, S.; Yang, T.; Liu, S.; Han, X.; Mao, X. Cluster mediated high strength and large ductility in a strip casting micro-alloyed steel. Acta. Mater. 2024, 276, 120102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gault, B.; Danoix, F.; Hoummada, K.; Mangelinck, D.; Leitner, H. Impact of directional walk on atom probe microanalysis. Ultramicroscopy 2012, 113, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Chen, H.; Riyahi khorasgani, A.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Li, T.; et al. Revealing the influence of Mo addition on interphase precipitation in Ti-bearing low carbon steels. Acta. Mater. 2022, 223, 117475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Jin, S.; Hu, R.; Xue, F.; Sha, G. Ion-irradiation-induced clustering in Fe-Mn-Ni-(Si) steels: Nucleation, growth and chemistry evolution. J. Nucl. Mater. 2022, 560, 153477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G.K.; Hall, W.H. X-ray line broadening from filed aluminium and wolfram. Acta Metall. 1953, 1, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebayashi, S.; Kunieda, T.; Yoshinaga, N.; Ushioda, K.; Ogata, S. Comparison of the dislocation density in martensitic steels evaluated by some X-ray diffraction methods. ISIJ Int. 2010, 50, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.-W.; Chen, P.-Y.; Huang, C.-Y.; Yang, J.-R. Interphase precipitation of nanometer-sized carbides in a titanium–molybdenum-bearing low-carbon steel. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 6264–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Miyamoto, G.; Shinbo, K.; Furuhara, T. Weak influence of ferrite growth rate and strong influence of driving force on dispersion of VC interphase precipitation in low carbon steels. Acta Mater. 2020, 186, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikmukhametov, I.; Beladi, H.; Wang, J.; Hodgson, P.D.; Timokhina, I. The effect of strain on interphase precipitation characteristics in a Ti-Mo steel. Acta Mater. 2019, 170, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.W.; Chen, C.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Huang, C.Y.; Yang, J.R. Orientation relationship transition of nanometre sized interphase precipitated TiC carbides in Ti bearing steel. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2010, 26, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q. Cluster strengthening in aluminium alloys. Scr. Mater. 2014, 84–85, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, R.; Ågren, J. A model for interphase precipitation based on finite interface solute drag theory. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 4791–4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Deformation mechanism of ferrite in a low carbon Al-killed steel: Slip behavior, grain boundary evolution and GND development. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 842, 143093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weygand, D.; Mrovec, M.; Hochrainer, T.; Gumbsch, P. Multiscale Simulation of Plasticity in bcc Metals. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2015, 45, 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.M.; Rao, S.I.; Uchic, M.D.; Dimiduk, D.M.; El-Awady, J.A. Microstructurally based cross-slip mechanisms and their effects on dislocation microstructure evolution in fcc crystals. Acta Mater. 2015, 85, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Number Density/×1023 m−3 | Volume Fraction/% | Average Guinier Radius/nm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 120 s | 1.88 | 0.0033 | 0.62 |

| 1800 s | 1.82 | 0.0155 | 0.98 |

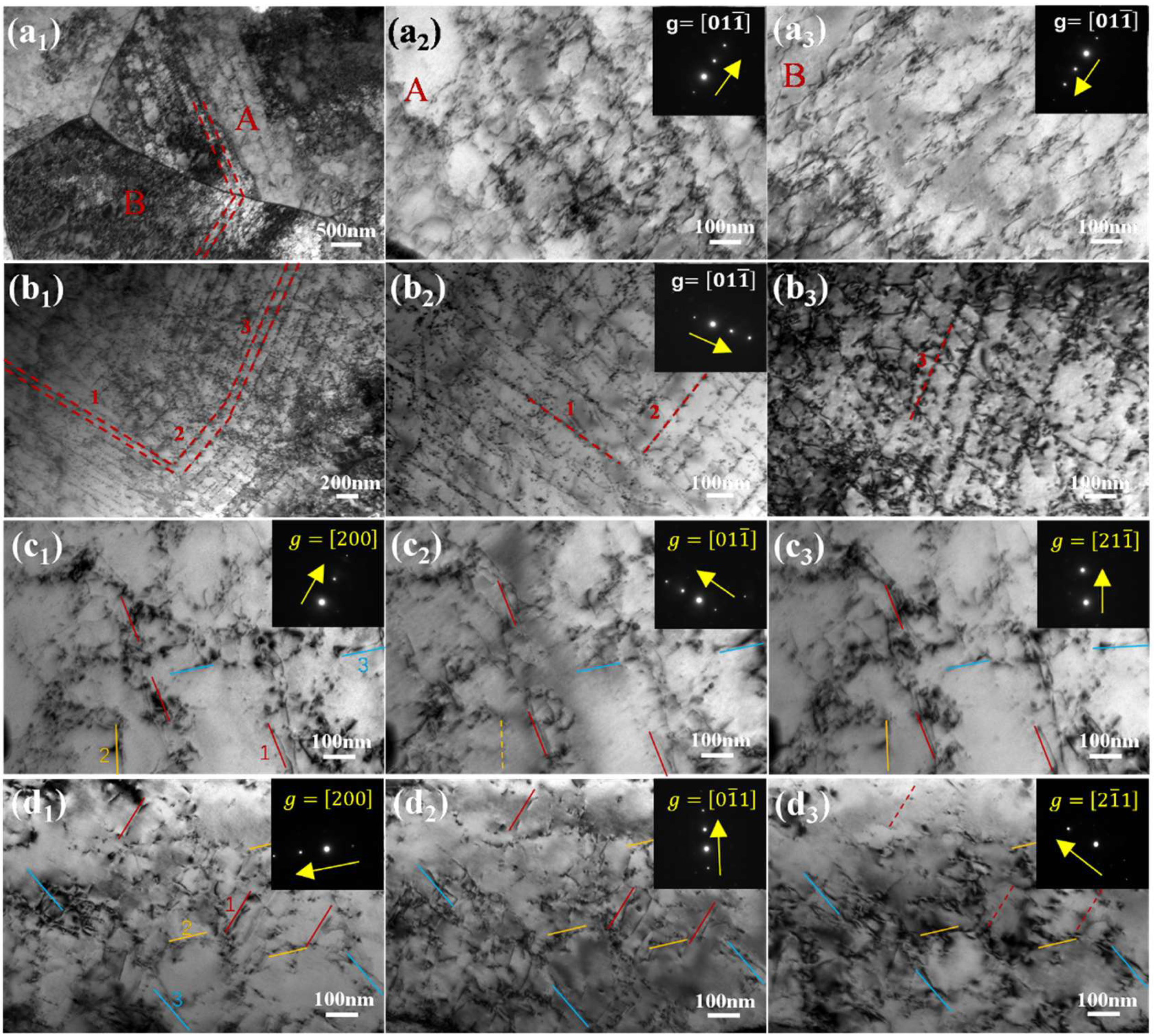

| Sample | b | Dislocation Type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 120s-1 | √ | √ | √ | Screw | |||

| 120s-2 | √ | × | √ | Mixed | |||

| 120s-3 | √ | √ | √ | Mixed | |||

| 1800s-1 | √ | √ | × | Screw | |||

| 1800s-2 | √ | √ | √ | Mixed | |||

| 1800s-3 | √ | √ | √ | Screw |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, H.; Huang, Y.; Lu, J.; Gao, J.; Zhao, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Mao, X. Evolution of Cluster Morphology and Its Impact on Dislocation Behavior in a Strip-Cast HSLA Steel. Materials 2025, 18, 5671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245671

Yu H, Huang Y, Lu J, Gao J, Zhao H, Wu H, Zhang C, Wang S, Mao X. Evolution of Cluster Morphology and Its Impact on Dislocation Behavior in a Strip-Cast HSLA Steel. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245671

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Huiwen, Yuhe Huang, Jun Lu, Junheng Gao, Haitao Zhao, Honghui Wu, Chaolei Zhang, Shuize Wang, and Xinping Mao. 2025. "Evolution of Cluster Morphology and Its Impact on Dislocation Behavior in a Strip-Cast HSLA Steel" Materials 18, no. 24: 5671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245671

APA StyleYu, H., Huang, Y., Lu, J., Gao, J., Zhao, H., Wu, H., Zhang, C., Wang, S., & Mao, X. (2025). Evolution of Cluster Morphology and Its Impact on Dislocation Behavior in a Strip-Cast HSLA Steel. Materials, 18(24), 5671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245671