Vertical Drainage Performance of a Novel Anti-Clogging Plastic Vertical Drainage Board for Soda-Residue-Stabilized Soil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soda Residue and Drainage Boards

2.1.1. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Soda Residue

2.1.2. Structural Improvement of Plastic Drainage Boards

2.2. Experimental Apparatus and Methods

3. Results

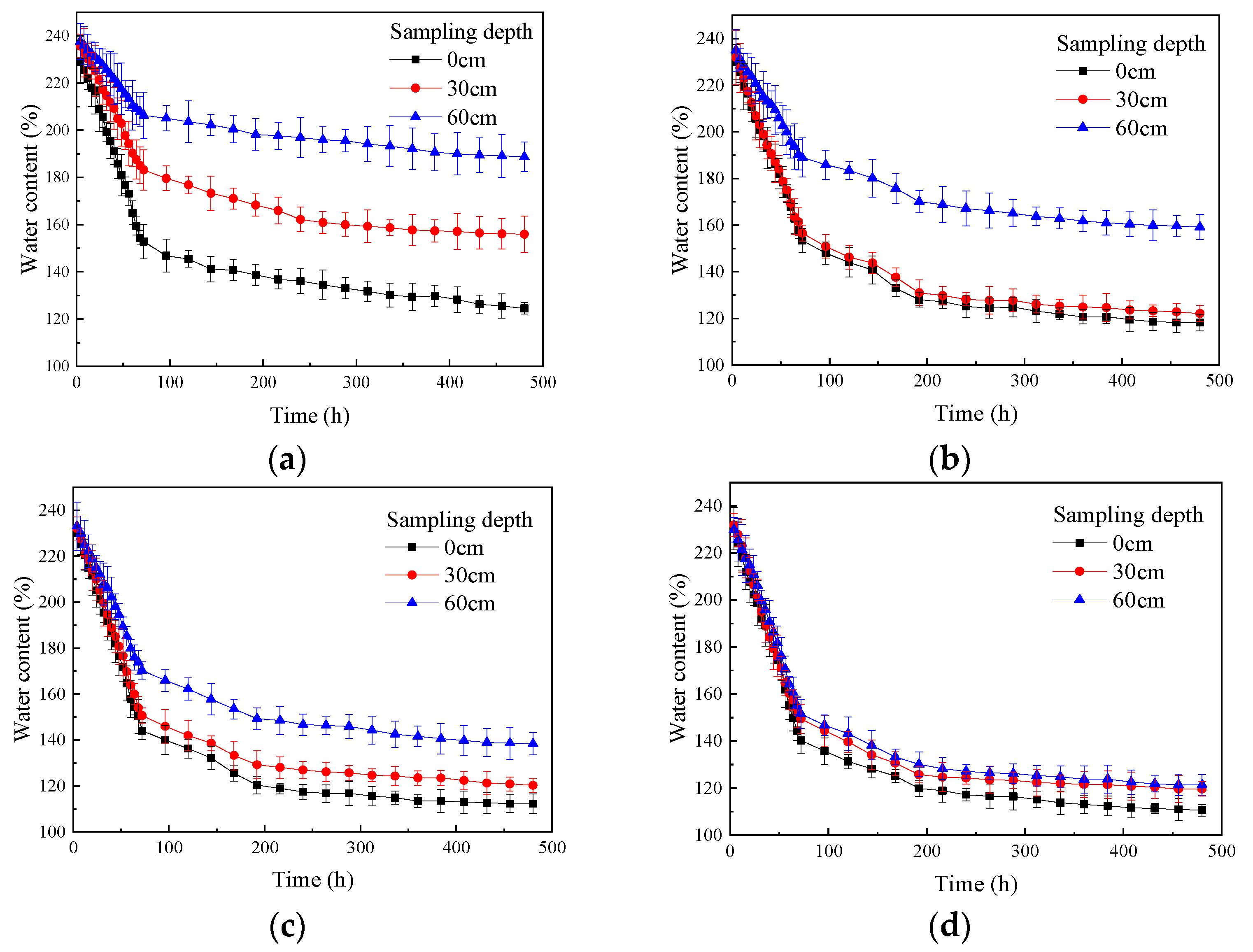

3.1. Water Content Change

- Initially, the content of free water in the soda residue was relatively high, and during the early stage of the test, a large amount of free water was extracted. As the test progressed, the free water content decreased, while bound water was generally not extracted.

- As water in the pores between the soda residue particles was drawn out, the pores were gradually compressed, the drainage channels became narrower, the seepage rate slowed down, and thus the rate of water content reduction decreased.

- Pore compression hinders the effective downward transmission of negative pressure, weakening the drainage driving force (negative pore water pressure).

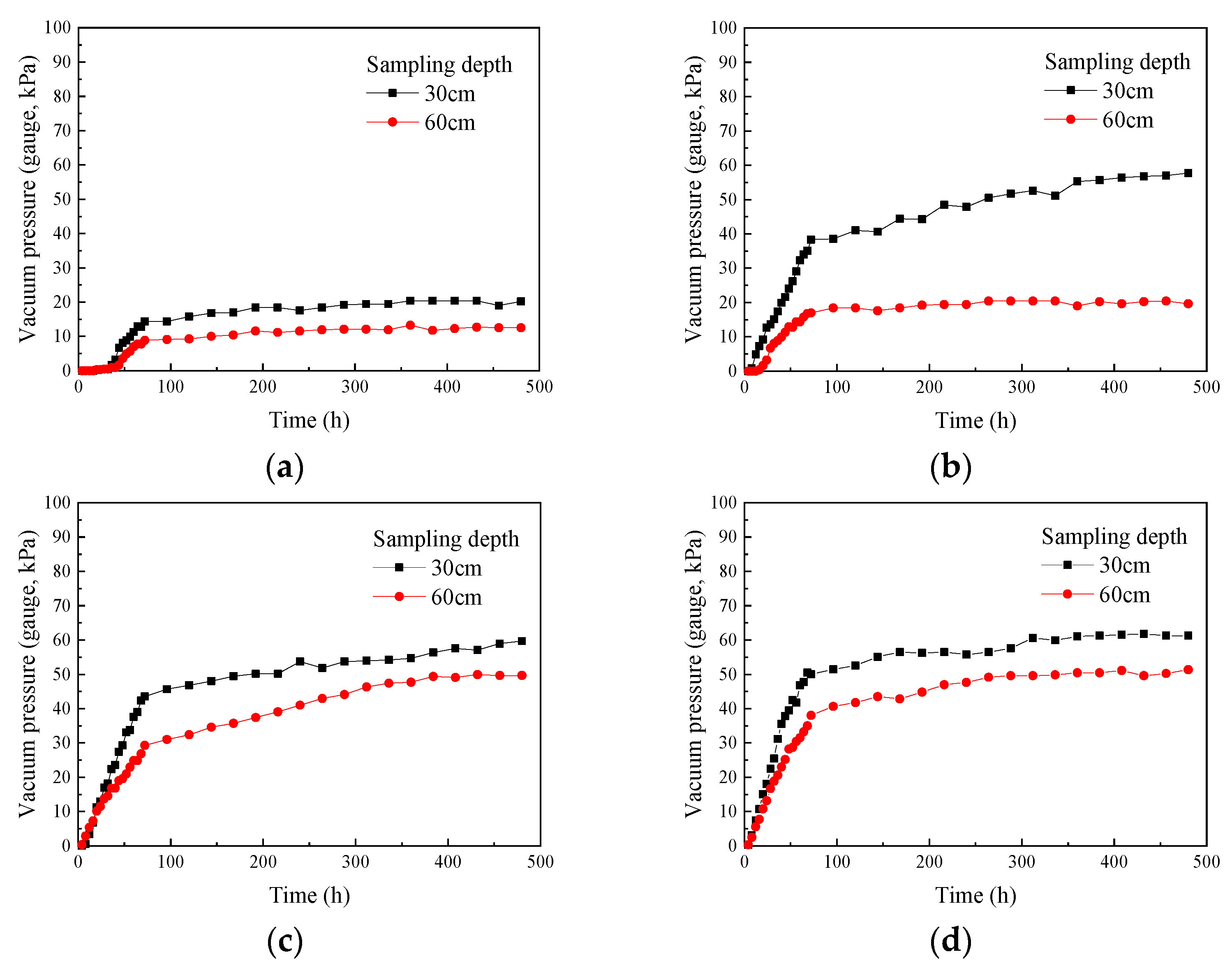

3.2. Vacuum Pressure Change

3.3. Surface Settlement

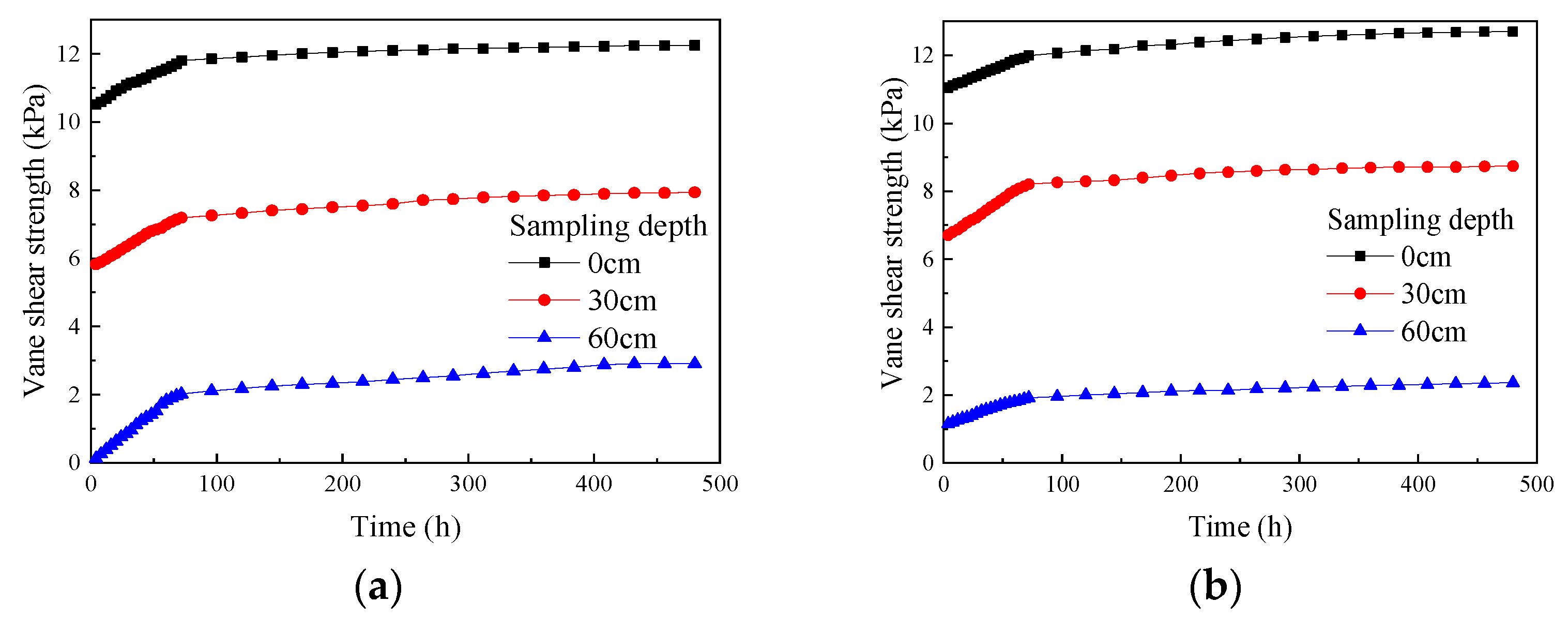

3.4. Vane Shear Strength

- As pointed out in Section 3.1, the water content increased with increasing sampling depth. The higher water content in the lower soil layers led to greater pore water pressure, reducing the effective stress in the lower soil and resulting in lower strength.

- As detailed in Section 3.2, the vacuum pressure in the lower layers of soda residue was lower. The lower vacuum pressure in the lower soil layers led to smaller absolute values of negative pore water pressure formed during the vacuum preloading process, further reducing the effective stress in the lower soil and resulting in lower strength.

- The lower water content and higher vacuum pressure in the upper soil promoted the rearrangement of soda residue particles, increasing the compactness, increasing the contact area between the particles, increasing the internal friction angle, and significantly improving the strength.

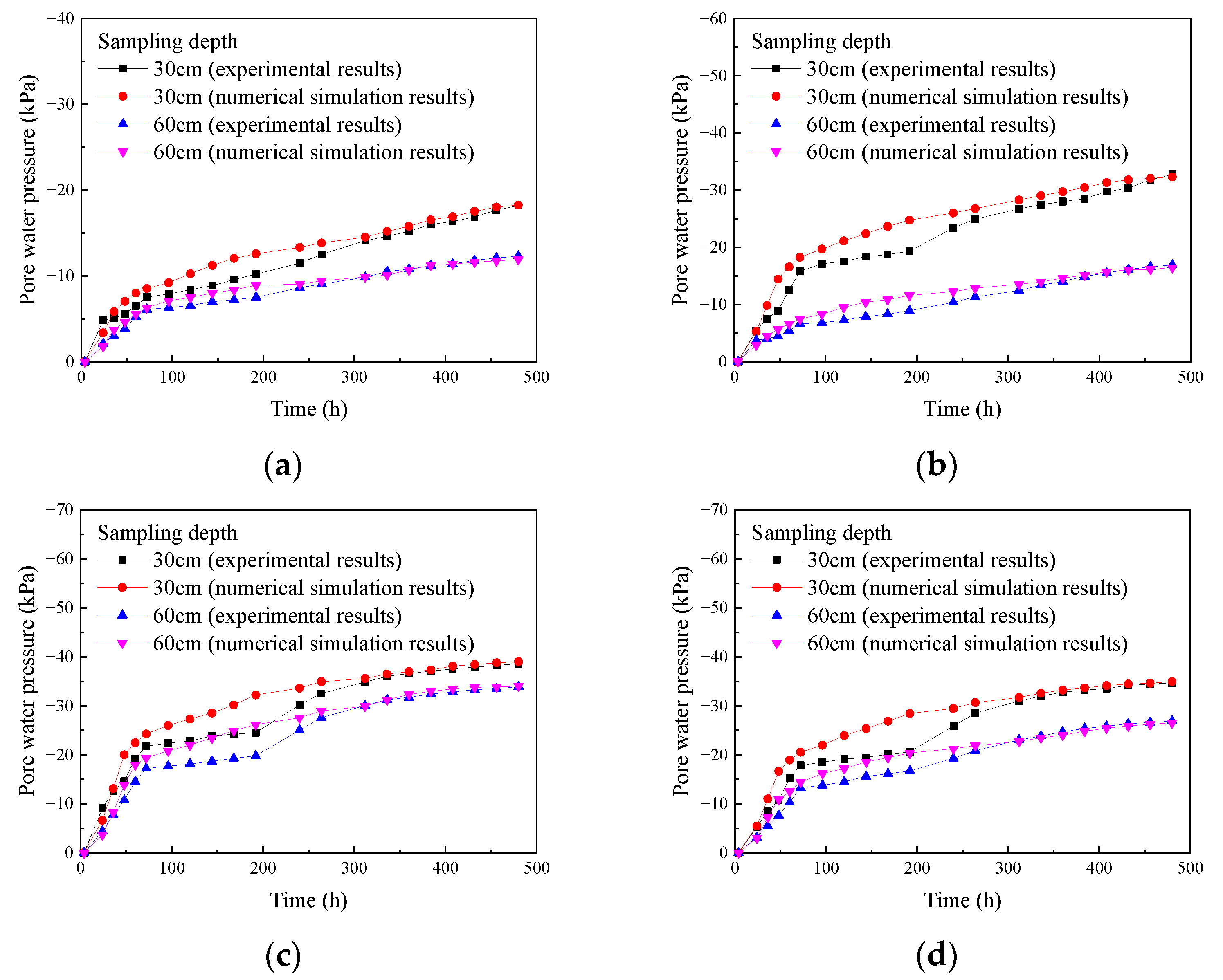

3.5. Pore Water Pressure

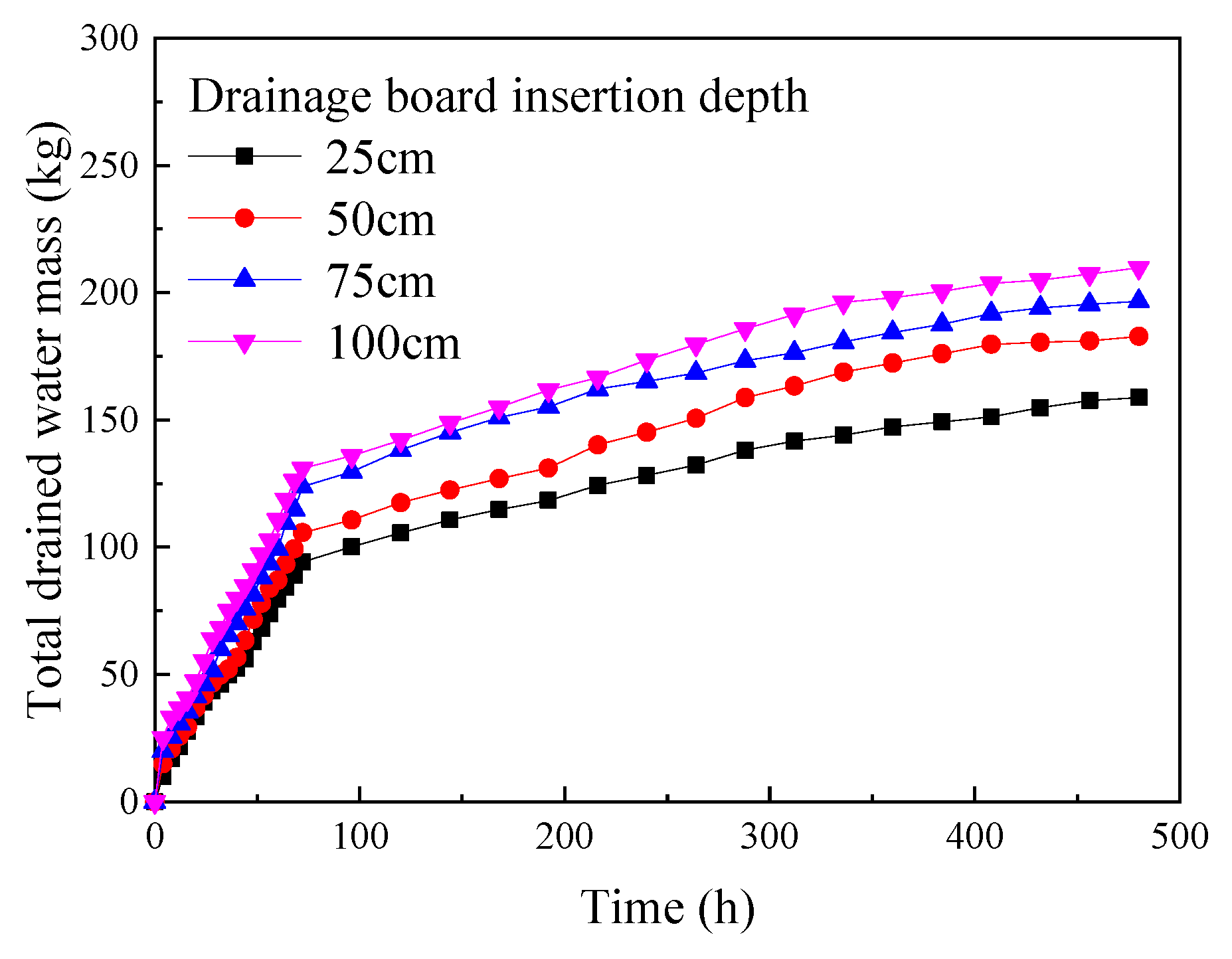

3.6. Total Drained Water Mass

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of the Strength Growth Mechanism of Soda Residue

4.2. Verification of the Evolution of Pore Water Pressure

4.3. Analysis of the Anti-Clogging Effect of the Novel Drainage Board

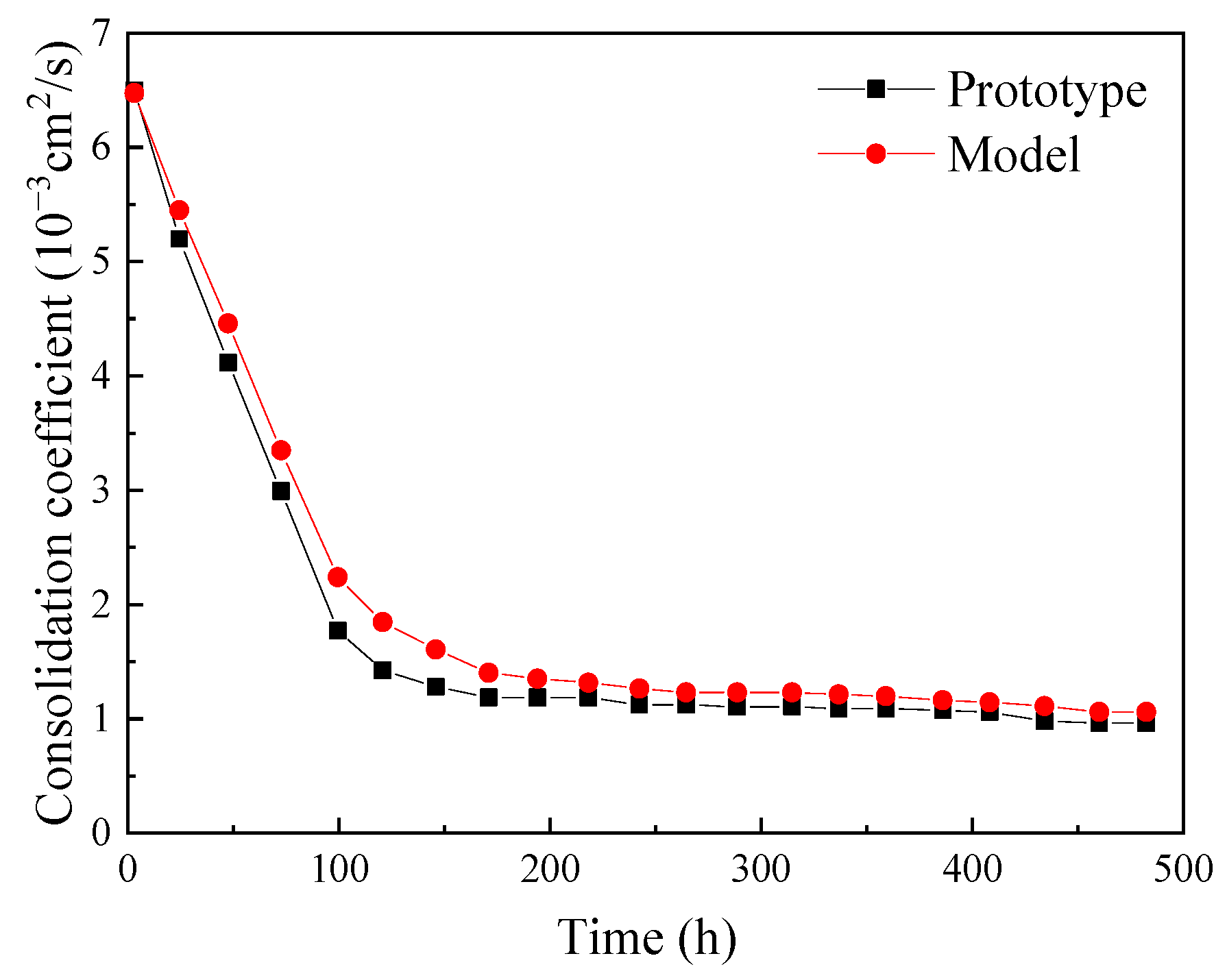

4.4. Generalizing to Actual Dimensions

5. Conclusions

5.1. Fundamental Conclusions

- During the vacuum preloading process, the decrease in the water content of the soda residue occurs first, whereas the increase in total drainage volume and vane shear strength lags behind the reduction in water content, and the volume decrease in the soda residue further lags behind the increase in the total drainage volume.

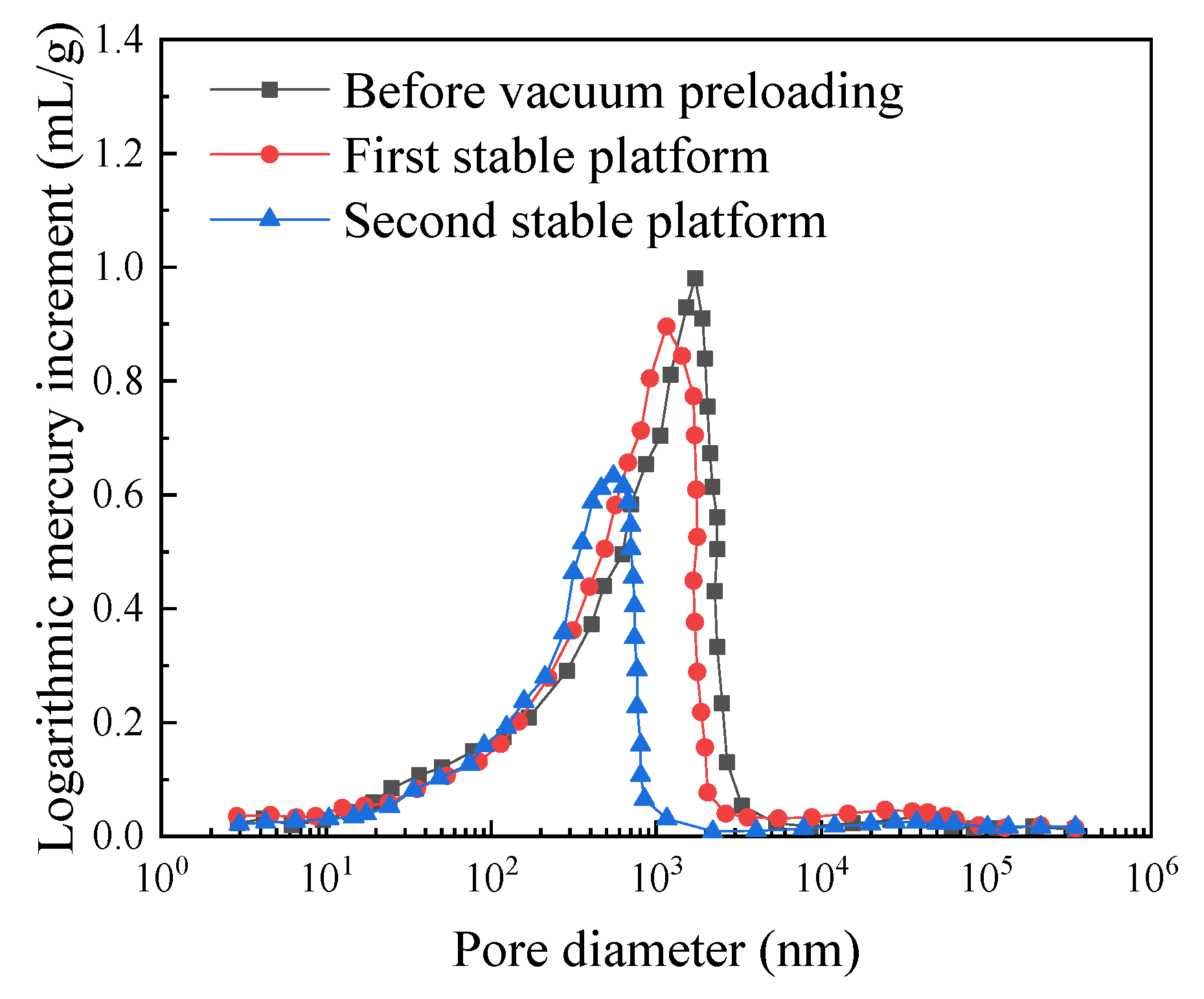

- During vacuum preloading, the increase in the pore water pressure (absolute value) of the soda residue is influenced by both the decrease in total stress and the increase in effective stress, exhibiting a typical double-plateau curve. The first stage of pore water pressure (absolute value) increase is mainly attributed to the decrease in total stress caused by the reduction in water content and self-weight of the soda residue, whereas the second stage is primarily governed by the increase in effective stress resulting from the reduction in pore volume and pore diameter.

- The mechanical properties and anti-clogging performance of drainage boards are highly dependent on their structural configuration. Introducing a wire mesh between the filter core and the geotextile significantly enhances the tensile and bending strength of the drainage board without noticeably compromising its drainage performance.

5.2. Applied Conclusions

- The type Y anti-clogging plastic drainage board (geotextile + wire mesh + filter core) exhibits the most balanced performance in terms of permeability, anti-clogging ability, tensile strength and bending strength and is suitable for vacuum preloading of soda residue with high water content.

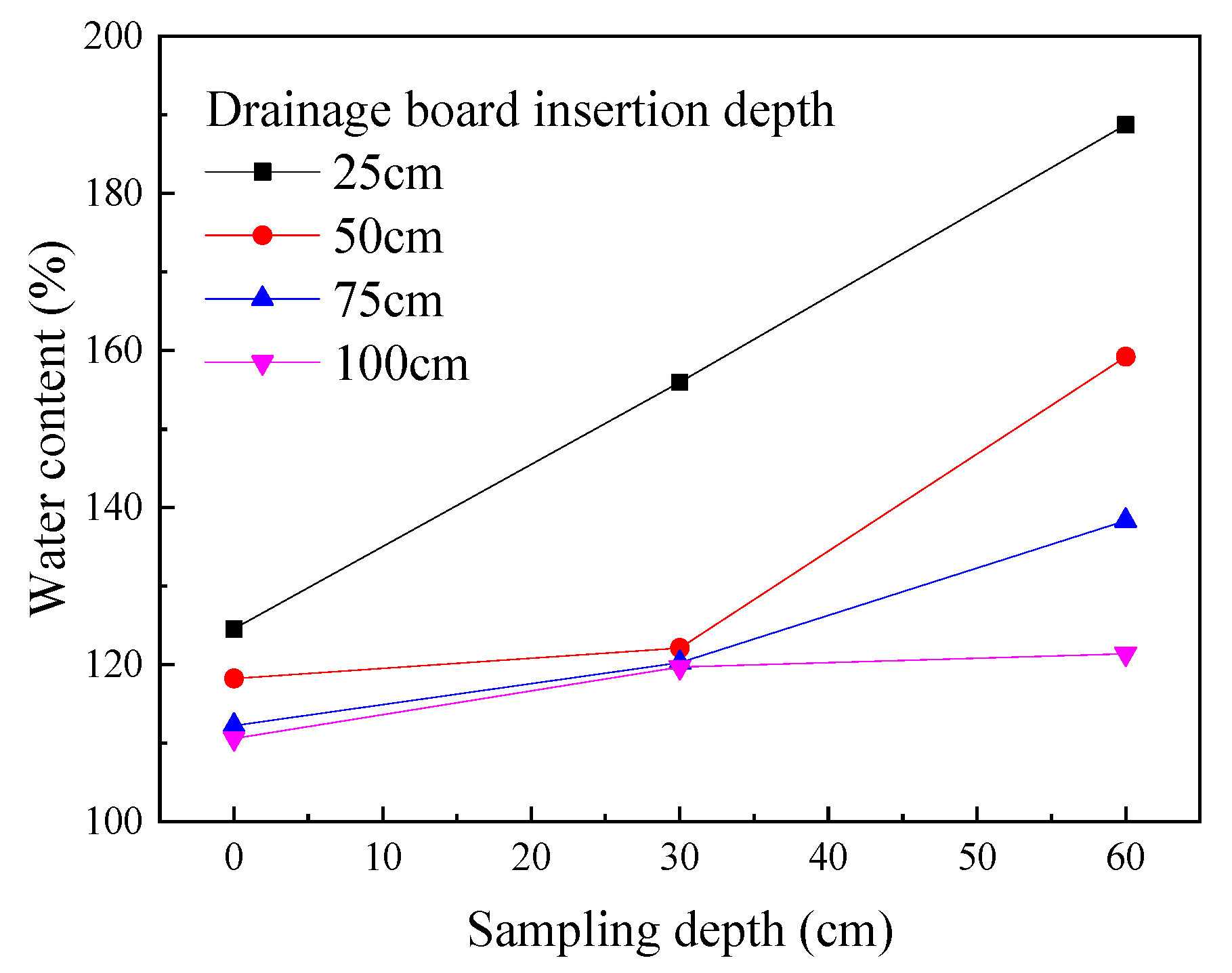

- The insertion depth of the drainage board significantly affects drainage efficiency, vacuum transmission rate, and strength development of the soda residue. The effective reinforcement range of the drainage board is not limited to the insertion depth but also extends below the bottom of the drainage board.

- When extrapolating the research results to on-site field conditions, geometric parameters such as the effective drainage range (radius of influence of drainage boards), drainage depth and drainage board spacing should be scaled by the similarity ratio, whereas the consolidation time scale should be scaled by the square of the similarity ratio.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Gong, X.; Chen, T. Experimental and numerical simulation studies on creep behavior of soda residue soil. China Civ. Eng. J. 2024, 57, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhu, Z. Experimental Investigation into Draining Consolidation Behavior of Soda Residue Soil Under Vacuum Preloading-Electro-Osmosis. J. South China Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2006, 34, 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Pu, Y.; Yan, W.; Guo, W.; Wang, H. Microstructure and Chloride Ion Dissolution Characteristics of Soda Residue. J. South China Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 45, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, J.W.; Bodamer, R.M. Determination of the discharge capacity of buckled PVD’s. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Geosynthetics, Berlin, Germany, 21–25 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J.; Jiang, E.; Yang, T.; Zhao, X.; Yue, Z.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, C. Research on Mechanical Properties and Mechanism of Soda Residue Soil for Road. Highway 2024, 69, 365–371. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, D.; Xu, S.; Zong, Z. Experimental Study on Strength Properties and Water Stability of Soda Residue Soft Soil. Highway 2020, 65, 212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Žurinskas, D.; Vaičiukynienė, D.; Stelmokaitis, G.; Doroševas, V. Clayey Soil Strength Improvement by Using Alkali Activated Slag Reinforcing. Minerals 2020, 10, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Shi, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Feng, X.; Zhou, L. Strength properties of dredged soil at high water content treated with soda residue, carbide slag, and ground granulated blast furnace slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 242, 118126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Tang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, K.; Li, H.; Zhu, Z.; Yin, W. Mechanical Properties Test and Enhancement Mechanism of Lime Soil Modified by High Content Soda Residue for Road Use. Coatings 2022, 12, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gong, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Xie, T. Study on Thixotropy of Soda Residue Soil and Its Strength Evolution After Disturbance. J. Tianjin Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2023, 56, 633–640. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Gong, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Xie, T. Study on cyclic cumulative pore pressure and strength evolution of soda residue soil under anisotropic consolidation. Rock Soil Mech. 2023, 44, 373–380+391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, T.; Yu, Z.; Zong, Z.; Li, J. Study on the unconfined compressive strength property and mechanism of soda residue soil. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2024, 42, 5085–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Huang, B.; Zhan, C.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, M. Mechanical properties and mechanisms of soda residue and fly ash stabilized soil. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yan, N.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Bai, X.; Wang, Y. Mechanical Characteristics of Soda Residue Soil Incorporating Different Admixture: Reuse of Soda Residue. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, T.; Liang, T.; Zong, Z.; Li, J. Mechanical Properties and Dry–Wet Stability of Soda Residue Soil. Buildings 2023, 13, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, M.; Lu, Y.; Wu, J. Influence of Drainage Plate Parameters on Treatment Effect in Vacuum Preloading. J. Northeast. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2025, 46, 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Wang, H.; Fu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Jin, J.; Lyu, Y. Experimental Study on the Influence of Aeration Duration on the Reinforcing Effect of PHD & PVD Vacuum Preloading Treatment of Dredged Slurry Foundations. China J. Highw. Transp. 2025, 38, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yang, A.; Xu, F. Vacuum preloading reinforcement of soft dredger soil by modified fiber drainage plate. Rock Soil Mech. 2025, 46, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Jiang, A.; Li, X.; Liu, C.; Fu, X. Preliminary Study on Characteristics of Dredged Sludge Treated by Vacuum Preloading Using Non-filter Membrane Straw Drainage Bodies. J. Chang. River Sci. Res. Inst. 2025, 42, 94–100+110. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, H.; Li, J.; Feng, S.; Liu, A. Reinforcement effect and mechanism analysis of dredged sludge treated by alternating prefabricated radiant drain vacuum preloading method. Geotext. Geomembr. 2023, 51, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Li, J.; Feng, S.; Ma, T.; Zhang, G.; Yu, S. Reinforcement effectiveness of stacked prefabricated vertical drain (S-PVD) vacuum preloading method: A case study. Geotext. Geomembr. 2025, 53, 1266–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, H.; Yuan, X.; Shan, W. Analysis of the Effectiveness of the Step Vacuum Preloading Method: A Case Study on High Clay Content Dredger Fill in Tianjin, China. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, J. Anti-clogging mechanism of freeze-thaw combined with step vacuum preloading in treating landfill sludge. Environ. Res. 2023, 218, 115059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rujikiatkamjorn, C.; Indraratna, B.; Chu, J. Numerical modelling of soft soil stabilized by vertical drains, combining surcharge and vacuum preloading for a storage yard. Can. Geotech. J. 2007, 44, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rujikiatkamjorn, C.; Indraratna, B.; Chu, J. 2D and 3D numerical modeling of combined surcharge and vacuum preloading with vertical drains. Int. J. Geomech. 2008, 8, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lou, Q.; Wang, X.; Gong, Y.; Li, X.; Fu, H. Evaluation of Heating Time on Vacuum Preloading Treatment. Buildings 2024, 14, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Qiu, C.; Li, Y.; You, Y. Performance of conductive plastic vertical drainage board under vacuum preloading combined with electro-osmotic consolidation. In International Symposium on Environmental Vibration and Transportation Geodynamics; Springer: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Terzaghi, K. Theoretical Soil Mechanics; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1943; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

| Particle size (mm) | >0.420 | 0.420~0.177 | 0.177~0.149 | 0.149~0.074 | 0.074~0.010 | <0.010 |

| Mass ratio (%) | 1.20 | 1.92 | 2.10 | 4.50 | 80.10 | 10.18 |

| Natural Density | Relative Density | Water Content | Plastic Limit | Liquid Limit | Plasticity Index | Liquidity Index | Unit Weight | Dry Unit Weight | Void Ratio | Porosity | Saturation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | Gs | ω | ωp | ωl | Ip | Il | γ | γd | e | n | Sr |

| (g/cm3) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (kN/m3) | (kN/m3) | (%) | (%) | ||||

| 1.19 | 2.33 | 216.40 | 87.4 | 136.3 | 48.9 | 2.6 | 12.21 | 3.86 | 4.73 | 82 | 100.00 |

| Compression Modulus | Cohesion | Internal Friction Angle | Hydraulic Conductivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Es | c | φ | κ |

| (MPa) | (kPa) | (°) | (cm/s) |

| 1.1 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 1.4 × 10−5 |

| Filter Membrane | Filter Membrane and Filter Core Composite | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength (Dry State) | Tensile Strength (After 24 h Immersion) | Hydraulic Conductivity (After 24 h Immersion) | Effective Pore Size (O95) | Tensile Strength (at 10% Elongation) | Longitudinal Flow Rate (Under 350 kPa Lateral Pressure) |

| 25 N/cm | 20 N/cm | 6.6 × 10−4 cm/s | 0.075 mm | 1.5 MPa | 30 cm3/s |

| Standard Plastic Drainage Board | Type X Plastic Drainage Board | Type Y Plastic Drainage Board | Type Z Plastic Drainage Board | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydraulic conductivity | 6.6 × 10−4 cm/s | 1.7 × 10−3 cm/s | 1.7 × 10−3 cm/s | 3.9 × 10−4 cm/s |

| Filter membrane tensile strength (dry state) | 31.3 N/cm | 33.4 N/cm | 37.1 N/cm | 34.5 N/cm |

| Filter membrane tensile strength (after 24 h immersion) | 20.2 N/cm | 21.3 N/cm | 25.3 N/cm | 21.8 N/cm |

| Composite tensile strength (at 10% elongation) | 1.50 MPa | 1.60 MPa | 2.03 MPa | 1.88 MPa |

| Effective bending strength | 38 kPa | 38 kPa | 75 kPa | 38 kPa |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, A.; Liu, T.; Fan, R.; Zhang, H.; Liang, F.; Liu, X.; Song, G. Vertical Drainage Performance of a Novel Anti-Clogging Plastic Vertical Drainage Board for Soda-Residue-Stabilized Soil. Materials 2025, 18, 5661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245661

Yang A, Liu T, Fan R, Zhang H, Liang F, Liu X, Song G. Vertical Drainage Performance of a Novel Anti-Clogging Plastic Vertical Drainage Board for Soda-Residue-Stabilized Soil. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245661

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Aiwu, Tianli Liu, Ridong Fan, Hao Zhang, Fayun Liang, Xuelun Liu, and Guowei Song. 2025. "Vertical Drainage Performance of a Novel Anti-Clogging Plastic Vertical Drainage Board for Soda-Residue-Stabilized Soil" Materials 18, no. 24: 5661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245661

APA StyleYang, A., Liu, T., Fan, R., Zhang, H., Liang, F., Liu, X., & Song, G. (2025). Vertical Drainage Performance of a Novel Anti-Clogging Plastic Vertical Drainage Board for Soda-Residue-Stabilized Soil. Materials, 18(24), 5661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245661