Investigation of the Mechanical Properties of Miura-Ori Auxetic Woven Fabrics with Variable Initial Dihedral Fold Angles

Abstract

1. Introduction

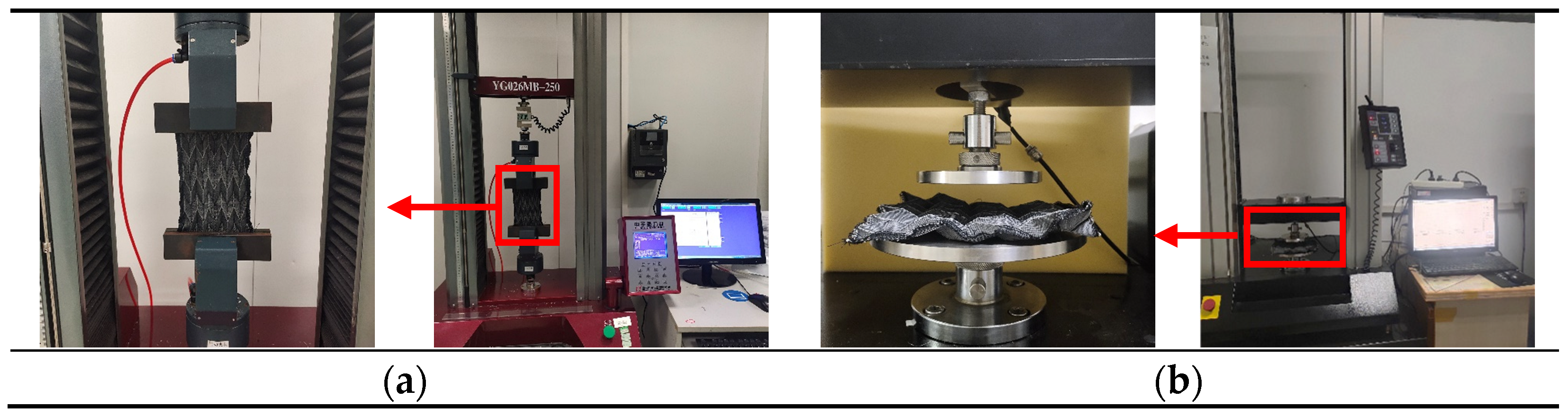

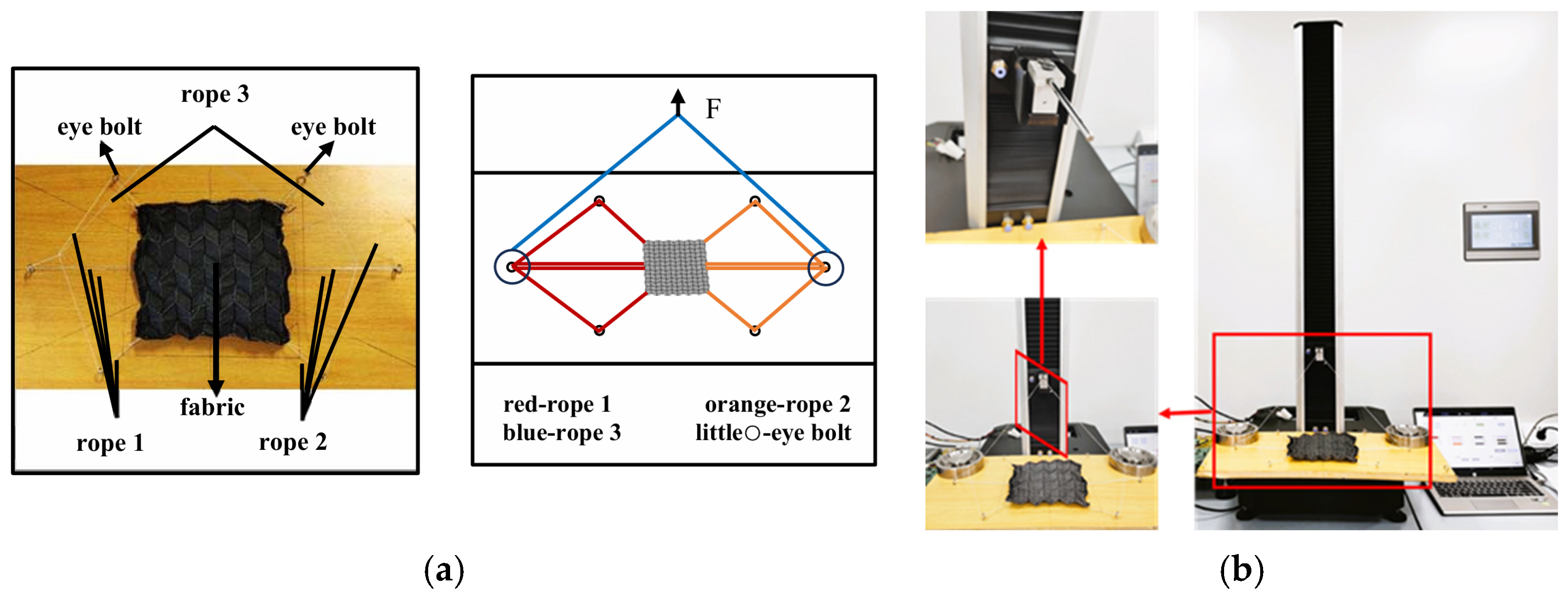

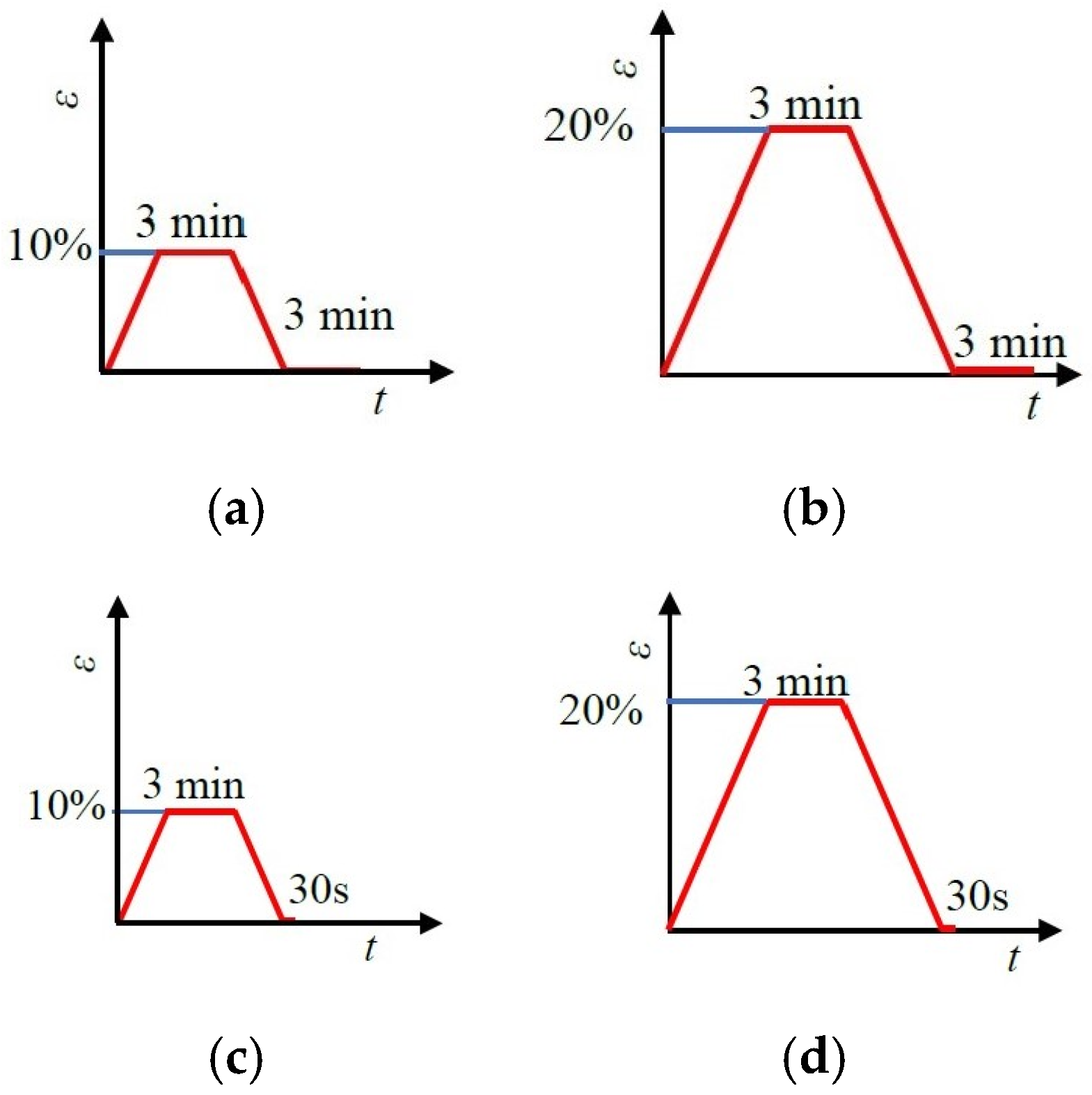

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

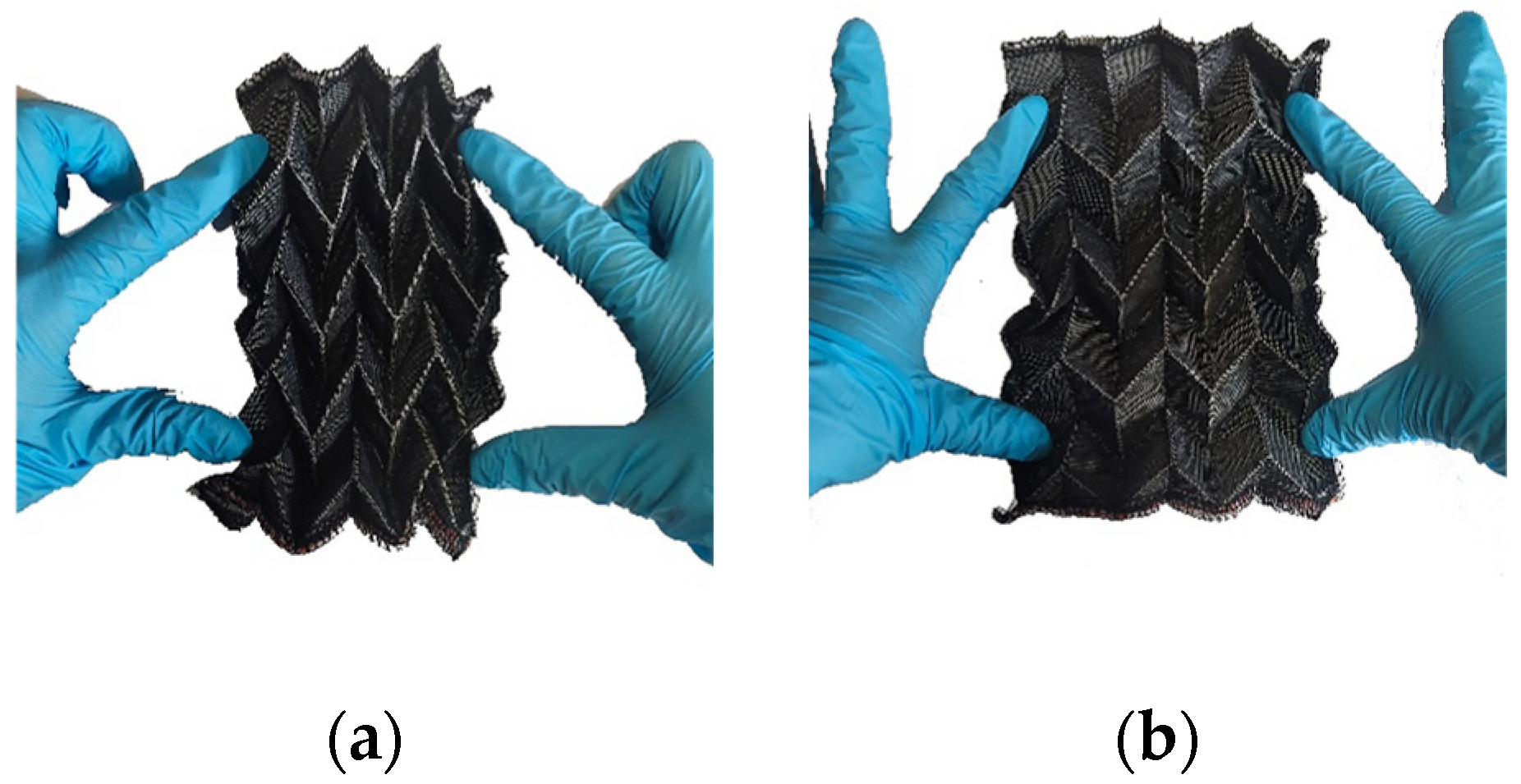

3.1. Air Permeability and Deformation Behavior

3.1.1. Air Permeability

3.1.2. Deformation Behavior

3.1.3. Stretching

3.1.4. Compressing

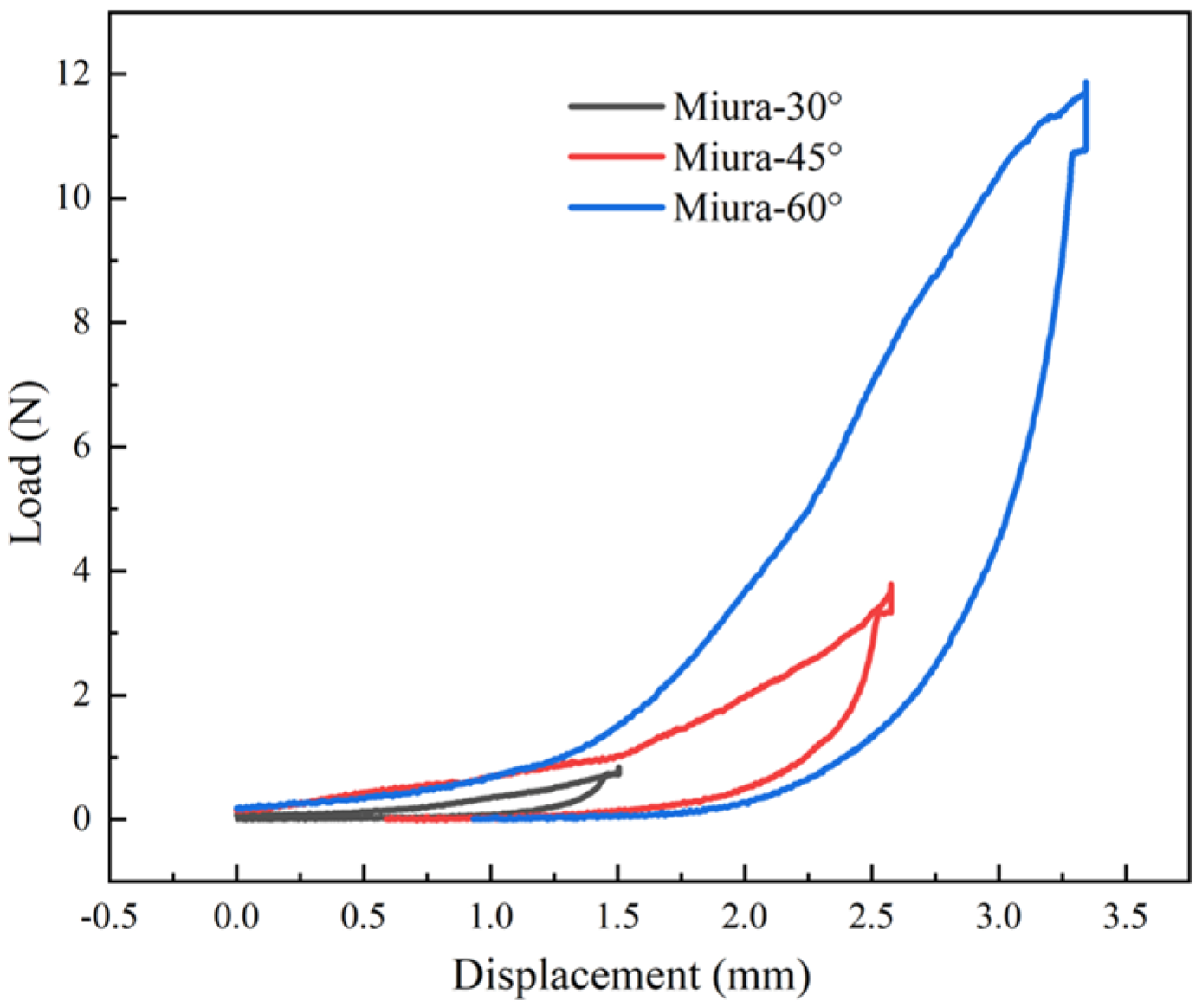

3.2. Rope Stretching Under Repeated Load

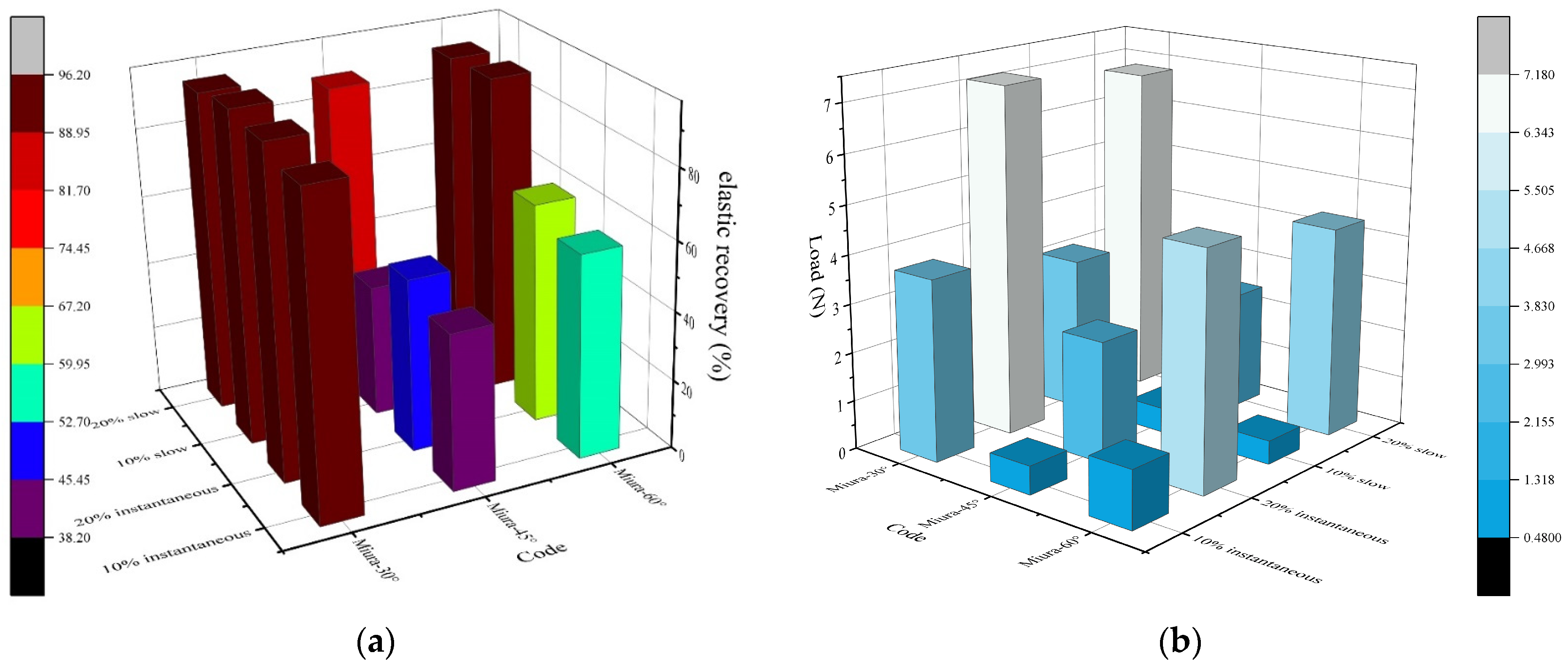

3.2.1. Elastic Recovery Rate

3.2.2. Elastic Recovery

4. Conclusions

- The Miura-ori auxetic woven fabrics exhibit favorable air permeability, which is positively correlated with the proportion of creased regions: when the Miura-ori structure angle was 30°, air permeability was better.

- According to the tensile and compressive properties of Miura-ori auxetic woven fabrics, Miura-45° showed the lowest recovery rate, which may be attributed to the minimal constraint on its elastic float yarns, which makes it difficult for the structure to recover.

- The initial cycle induced considerable deformation in the Miura-ori auxetic woven fabric, with subsequent cycles exhibiting stabilized behavior, confirming its structural stability under tensile loading: when the Miura-ori structure angle was 30°, the elastic recovery was better.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ren, X.; Das, R.; Tran, P.; Ngo, T.D.; Xie, Y.M. Auxetic metamaterials and structures: A review. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 023001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolken, H.M.A.; Zadpoor, A.A. Auxetic mechanical metamaterials. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 5111–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Behera, B.K. Auxetic fibrous materials and structures in medical engineering—A review. J. Text. Inst. 2022, 290, 2116549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, D.; Nguyen, H.; Fangueiro, R.; Ferreira, F.; Nguyễn, Q. Auxetic materials and structures in the automotive industry: Applications and insights. J. Reinf. Plast. Comp. 2025, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, D.; Zhang, M.L.H.; Hu, H. Auxetic materials for personal protection: A review. Phys. Status Solidi B 2022, 259, 202200324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyễn, H.; Fangueiro, R.; Ferreira, F.; Nguyen, Q.T. Auxetic materials and structures for potential defense applications: An overview and recent developments. Text. Res. J. 2023, 93, 5268–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y. 1-Introduction. In Auxetic Textiles; Hu, H., Zhang, M., Liu, Y., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Surjadi, J.U.; Gao, L.; Du, H.; Li, X.; Xiong, X.; Fang, N.X.; Lu, Y. Mechanical metamaterials and their engineering applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019, 21, 1800864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.S.; Hu, H. Sensors based on auxetic materials and structures: A review. Materials 2023, 16, ma16093603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Sharma, J.; Singh, O.; Behera, B.K. Auxetic textiles, composites and applications. Text. Prog. 2024, 56, 323–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; Li, Y.G.; Yan, T.H.; Liu, X.; Cao, J.Q.; Du, Z.Q. Influence of re-entrant hexagonal structure and helical auxetic yarn on the tensile and auxetic behavior of parametric fabrics. Text. Res. J. 2022, 92, 2605–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Du, Z.; Li, T. Structural design and characterization of highly elastic woven fabric containing helical auxetic yarns. Text. Res. J. 2020, 90, 809–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Du, Z. Structural design and performance characterization of stable helical auxetic yarns based on the hollow-spindle covering system. Text. Res. J. 2020, 90, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Zulifqar, A.; Hua, T.; Hu, H. Bi-stretch auxetic woven fabrics based on foldable geometry. Text. Res. J. 2019, 89, 2694–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, A.; Kumar, V.; Saraswat, H.; Weerasinghe, D.; Wild, K.; Hietel, D.; Dauner, M. Creating three-dimensional (3D) fiber networks with out-of-plane auxetic behavior over large deformations. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 2534–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, M.; Hu, H.; Etemadi, E. Geometric Analysis of Three-Dimensional Woven Fabric with in-Plane Auxetic Behavior. Polymers 2023, 15, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.J. Twists, Tilings, and Tessellations: Mathematical Methods for Geometric Origami; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. XV–XX. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Stampfli, J.J.; Xu, H.J.; Malkin, E.; Diaz, E.V. A vacuum-driven origami “magic-ball” soft gripper. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Robotics & Automation, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Melancon, D.; Gorissen, B.; García-Mora, C.J.; Hoberman, C.; Bertoldi, K. Multistable inflatable origami structures at the metre scale. Nature 2021, 592, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.; Cañón Bermúdez, G.S.; Liu, J.A.-C.; Oliveros Mata, E.S.; Evans, B.A.; Tracy, J.B.; Makarov, D. Reconfigurable magnetic origami actuators with on-board sensing for guided assembly. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2008751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Shao, Z.; Xie, Z.; Liu, J.; Pan, F.; He, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ling, X.; Peng, F.; et al. Soft origami gripper with variable effective length. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2000251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, H.; Lam, J.K.; Liu, S. Negative Poisson’s ratio weft-knitted fabrics. Text. Res. J. 2010, 80, 856–863. [Google Scholar]

- Schenk, M.; Guest, S.D. Geometry of Miura-folded metamaterials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 3276–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, K.; West, A.; DenHartog, E.; McCord, M. Auxetic deformation of the weft-knitted Miura-ori fold. Text. Res. J. 2020, 90, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Gu, L.; Liu, G.; Liu, Z.; Lu, D.; Du, Z. Design, preparation, and characterization of auxetic weft backed weave fabrics based on Miura origami structure. Text. Res. J. 2022, 92, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 5453:1997; Textiles—Determination of the Permeability of Fabrics to Air. State Bureau of Quality and Technical Supervision: Beijing, China, 1997.

- FZ/T 70006-2022; Stretch and Recovery Testing Method for Knits. China National Textile and Apparel Council: Beijing, China, 2022.

- ISO 20932-1:2018; Textiles—Determination of the Elastic Properties of Fabrics—Part 1: Strip Tests. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

| Correlation Analysis | Crease Ratio | 50 Pa | 100 Pa | 200 Pa | 500 Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crease Ratio | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.996 | 0.995 | 0.771 | 0.951 |

| Significance (2-tailed) | 0.058 | 0.062 | 0.439 | 0.200 | ||

| Covariance | 6.199 | 17.600 | 71.139 | 8.281 | 155.488 | |

| 50 Pa | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.982 | 0.711 | 0.975 | |

| Significance (2-tailed) | 0.120 | 0.497 | 0.143 | |||

| Covariance | 50.382 | 200.182 | 21.754 | 454.503 | ||

| 100 Pa | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.830 | 0.916 | ||

| Significance (2-tailed) | 0.377 | 0.263 | ||||

| Covariance | 824.344 | 102.754 | 1727.377 | |||

| 200 Pa | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.537 | |||

| Significance (2-tailed) | 0.639 | |||||

| Covariance | 18.588 | 152.010 | ||||

| 500 Pa | Pearson Correlation | 1 | ||||

| Significance (2-tailed) | ||||||

| Covariance | 4313.035 | |||||

| Code | Miura-30° | Miura-45° | Miura-60° |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gauge Length/mm | 150 | 130 | 100 |

| Pre-set Elongation/mm | 10 | 15 | 25 |

| Measured Elongation/mm | 1.79 ± 0.06 (3.39%) | 3.51 ± 0.16 (4.69%) | 1.21 ± 0.23 (19.08%) |

| Recovery Rate/% | 84.70 ± 0.20 (0.24%) | 78.37 ± 1.50 (1.92%) | 95.20 ± 0.92 (0.96%) |

| Strain/% | 1.00 ± 0.06 (2.56%) | 2.50 ± 0.17 (6.93%) | 1.23 ± 0.25 (20.40%) |

| Code | Miura-30° | Miura-45° | Miura-60° |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fabric Thickness/mm | 11.30 ± 0.43 (3.78%) | 17.57 ± 0.42 (2.37%) | 22.51 ± 0.08 (0.34%) |

| Maximum Stress/N | 0.81 ± 0.13 (16.37%) | 3.79 ± 0.03 (0.88%) | 11.84 ± 0.21 (1.75%) |

| Pressure/Pa | 26.00 ± 4.24 (16.32%) | 121.00 ± 1.00 (0.83%) | 377.00 ± 6.68 (1.77%) |

| Compression Work/mJ | 0.71 ± 0.10 (14.80%) | 3.29 ± 0.21 (6.44%) | 13.97 ± 0.48 (3.43%) |

| Recovery Work/mJ | 0.33 ± 0.04 (10.90%) | 1.04 ± 0.10 (10.04%) | 4.69 ± 0.23 (4.89%) |

| Recovery Rate/% | 46.48 | 31.62 | 33.58 |

| Linearity | 0.52 | 0.33 | 0.35 |

| Initial Stiffness IES/(N/m) | 246.66 | 870.14 | 671.50 |

| Code | Classification | Strain/% | Elastic Recovery Rate/% | Plastic Deformation Rate/% | Maximum Tensile Force/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miura-30° | Instantaneous Elasticity | 10 | 91.712 | 0.478 | 3.721 |

| 20 | 94.939 | 0.399 | 7.176 | ||

| Delayed Elasticity | 10 | 96.062 | 0.181 | 3.170 | |

| 20 | 93.365 | 0.503 | 6.809 | ||

| Miura-45° | Instantaneous Elasticity | 10 | 45.069 | 3.884 | 0.583 |

| 20 | 50.265 | 8.254 | 2.486 | ||

| Delayed Elasticity | 10 | 38.273 | 3.737 | 0.509 | |

| 20 | 88.351 | 0.933 | 2.424 | ||

| Miura-60° | Instantaneous Elasticity | 10 | 58.903 | 4.387 | 1.183 |

| 20 | 63.921 | 6.756 | 4.829 | ||

| Delayed Elasticity | 10 | 91.977 | 0.195 | 0.484 | |

| 20 | 91.197 | 1.015 | 4.320 |

| Code | Strain/% | Elastic Response Rate/% | Plastic Strain Rate/% | Maximum Tensile Force/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miura-30° | 10 | 95.567 | 0.209 | 3.324 |

| 20 | 93.601 | 0.447 | 6.523 | |

| Miura-45° | 10 | 43.903 | 2.172 | 0.427 |

| 20 | 42.335 | 9.448 | 2.666 | |

| Miura-60° | 10 | 69.832 | 1.265 | 0.682 |

| 20 | 55.067 | 8.236 | 4.717 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Q.; Tian, Y.; Du, Z. Investigation of the Mechanical Properties of Miura-Ori Auxetic Woven Fabrics with Variable Initial Dihedral Fold Angles. Materials 2025, 18, 5663. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245663

Xu Q, Tian Y, Du Z. Investigation of the Mechanical Properties of Miura-Ori Auxetic Woven Fabrics with Variable Initial Dihedral Fold Angles. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5663. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245663

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Qiaoli, Yuan Tian, and Zhaoqun Du. 2025. "Investigation of the Mechanical Properties of Miura-Ori Auxetic Woven Fabrics with Variable Initial Dihedral Fold Angles" Materials 18, no. 24: 5663. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245663

APA StyleXu, Q., Tian, Y., & Du, Z. (2025). Investigation of the Mechanical Properties of Miura-Ori Auxetic Woven Fabrics with Variable Initial Dihedral Fold Angles. Materials, 18(24), 5663. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245663