Influence of Spark Plasma Sintering Parameters on the Microstructure, Mechanical and Tribological Characteristics of Air-Milled Aluminum

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Investigating the effect of mechanical milling on the powder and sintered sample microstructure.

- Evaluating the influence of sintering temperature and pressure on the density and microstructure of both milled and unmilled aluminum.

- Assessing how sintering parameters and microstructure affect tribological and mechanical properties such as hardness and elastic modulus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation and Characterization

2.2. Tribological Tests

3. Results and Discussions

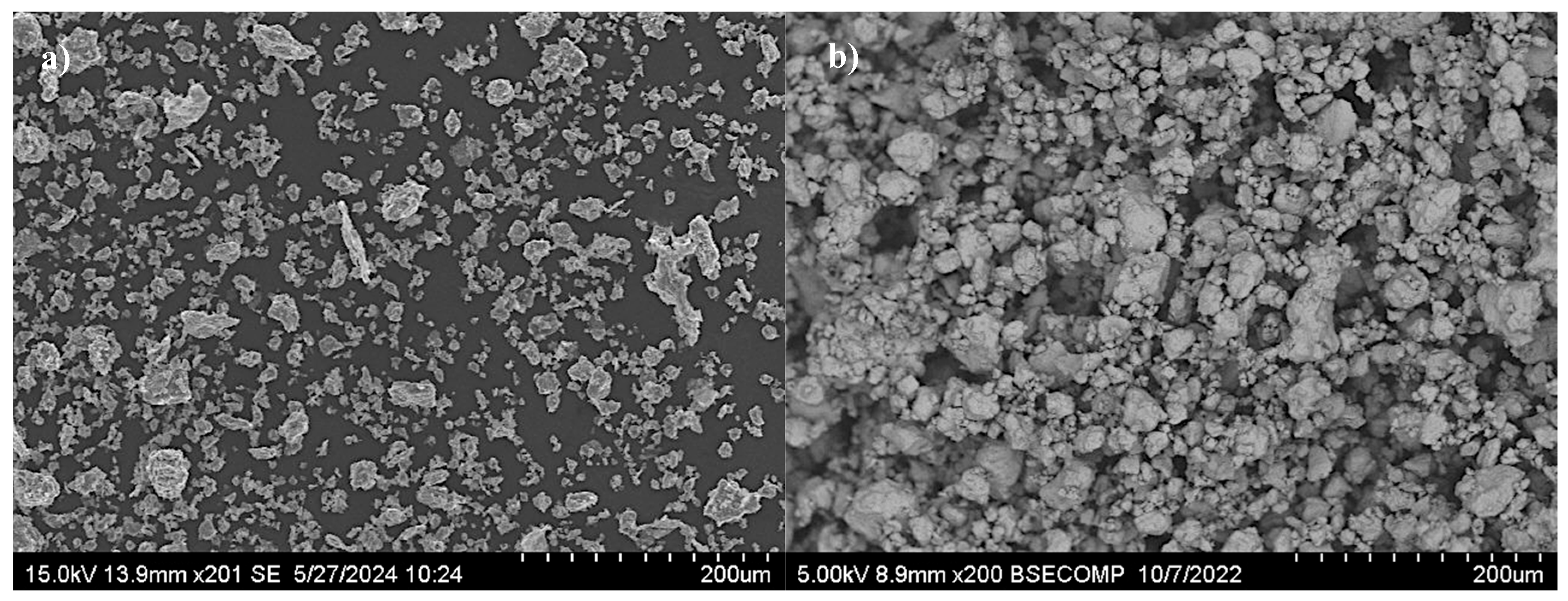

3.1. Microstructure of Powders

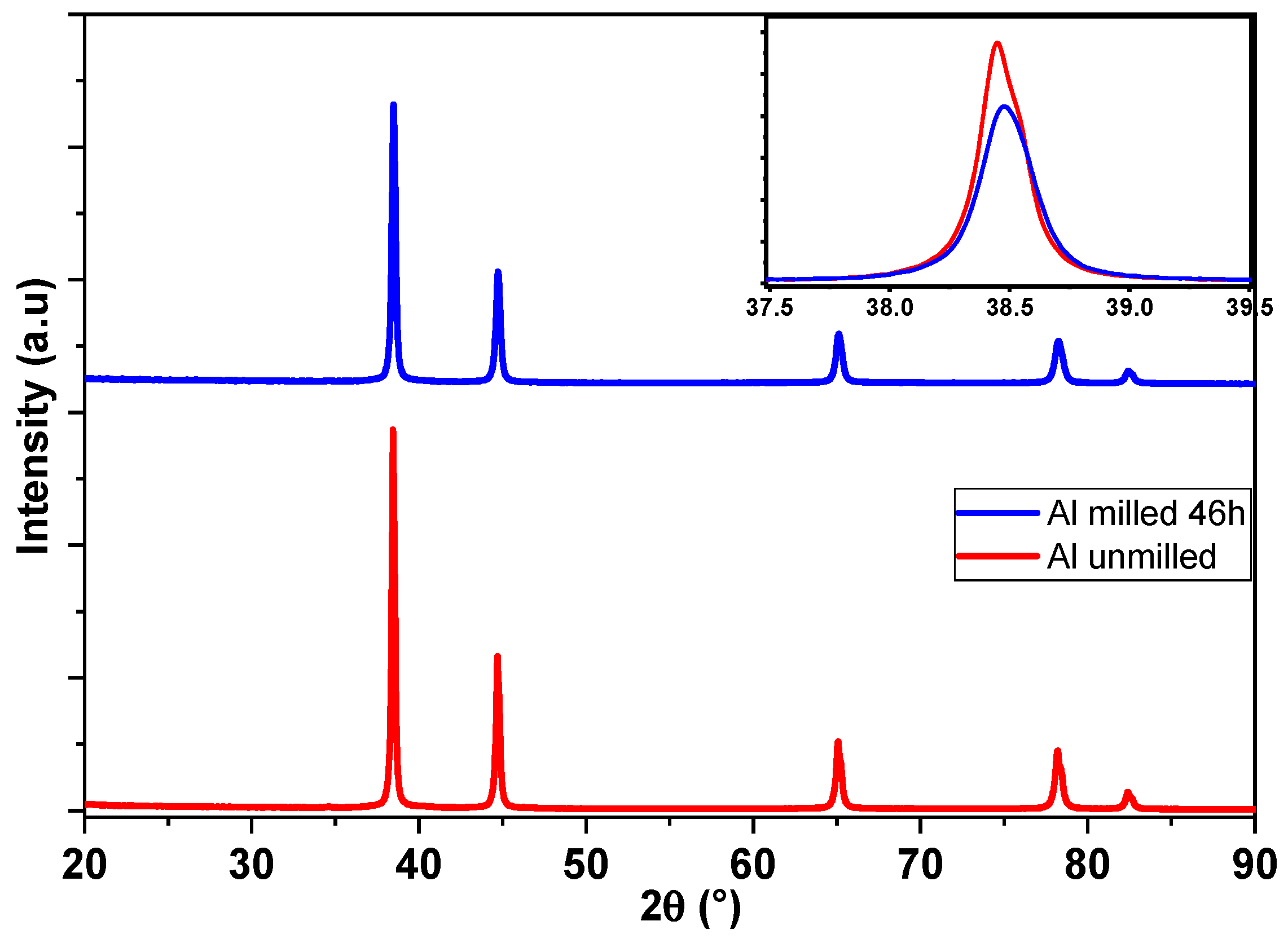

3.2. XRD Analysis of Powders

3.3. DSC of the Unmilled and Milled Powders

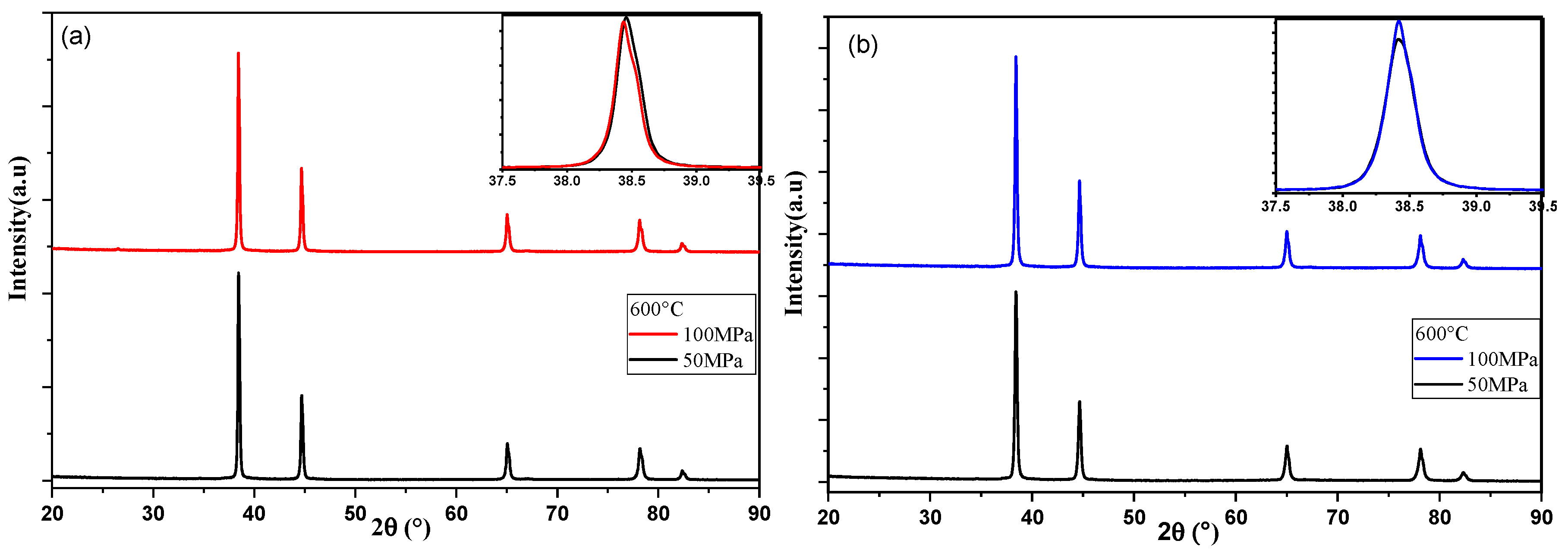

3.4. DRX of SPS-Consolidated Samples

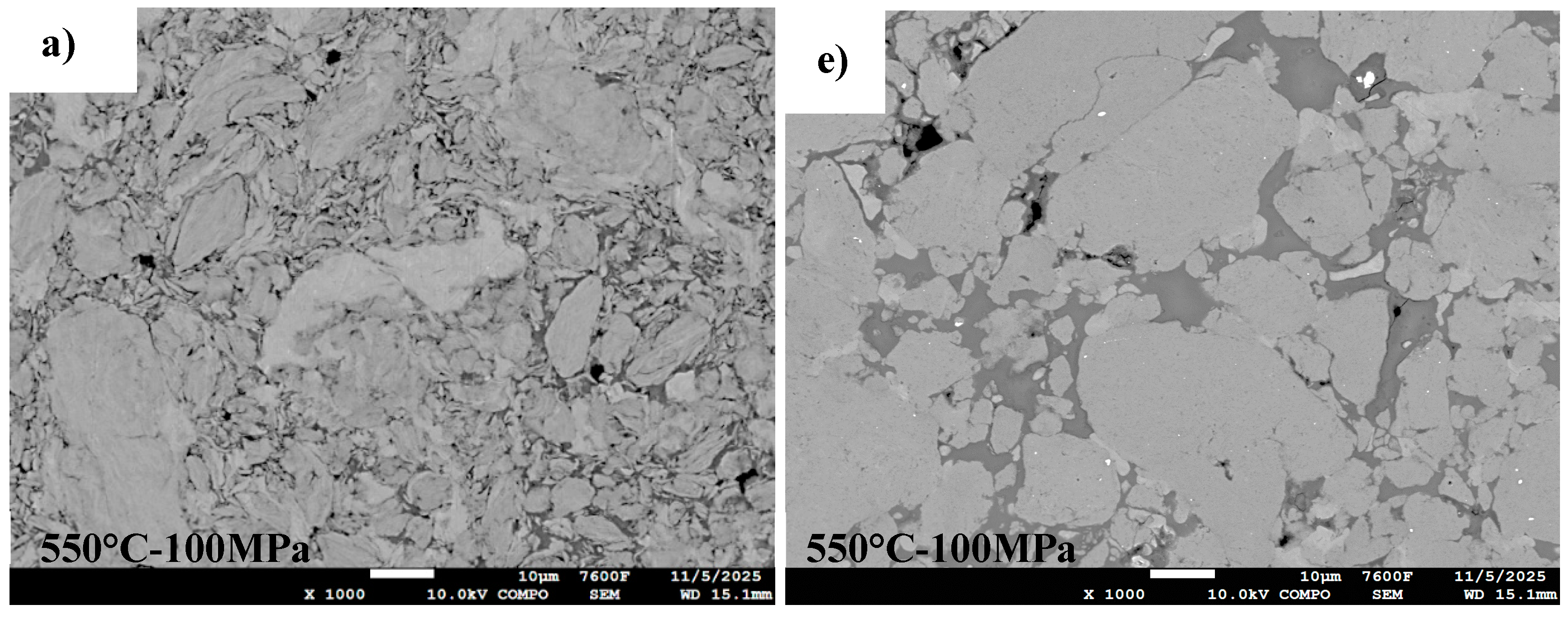

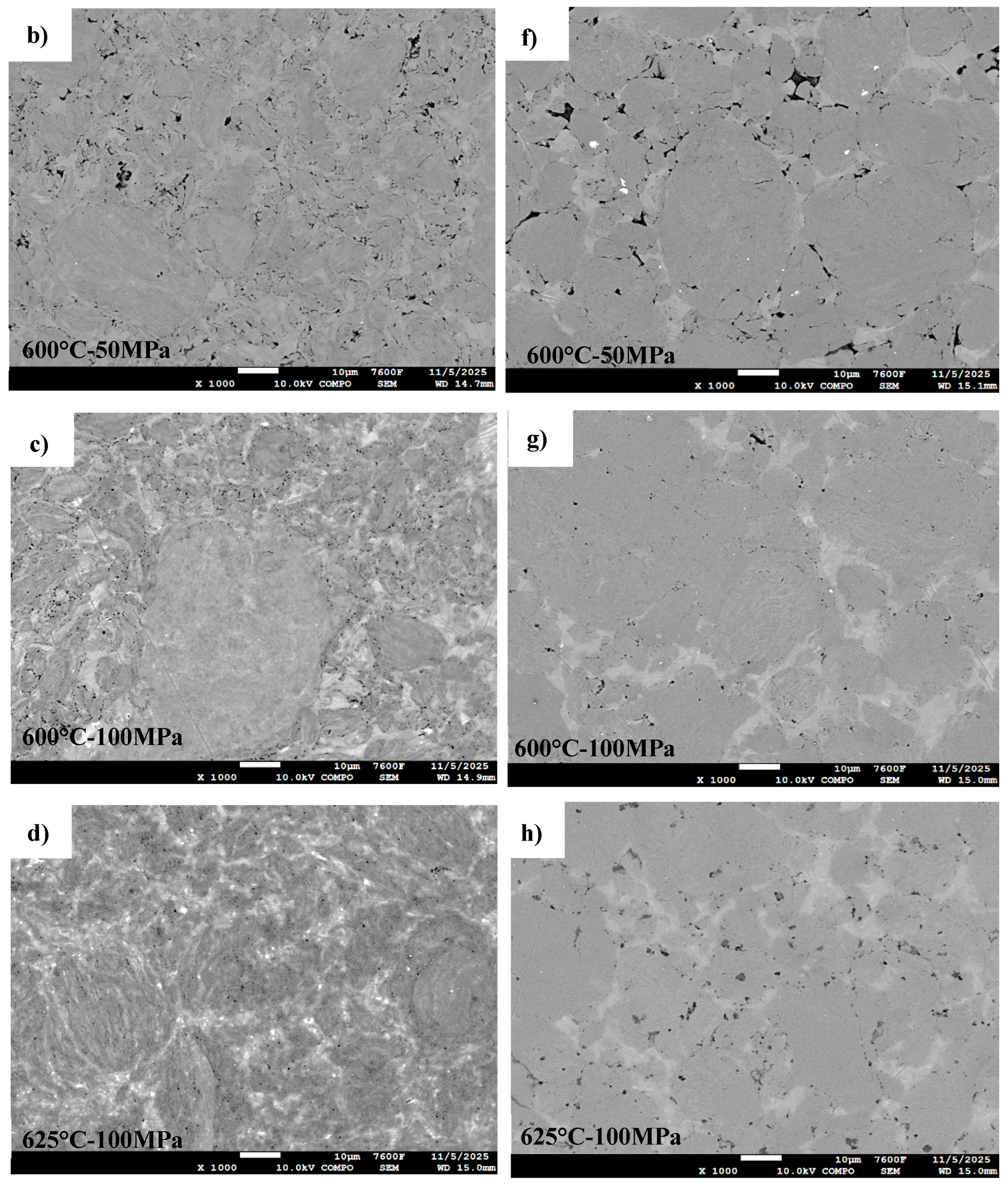

3.5. Microstructure of SPS-Consolidated Pellets

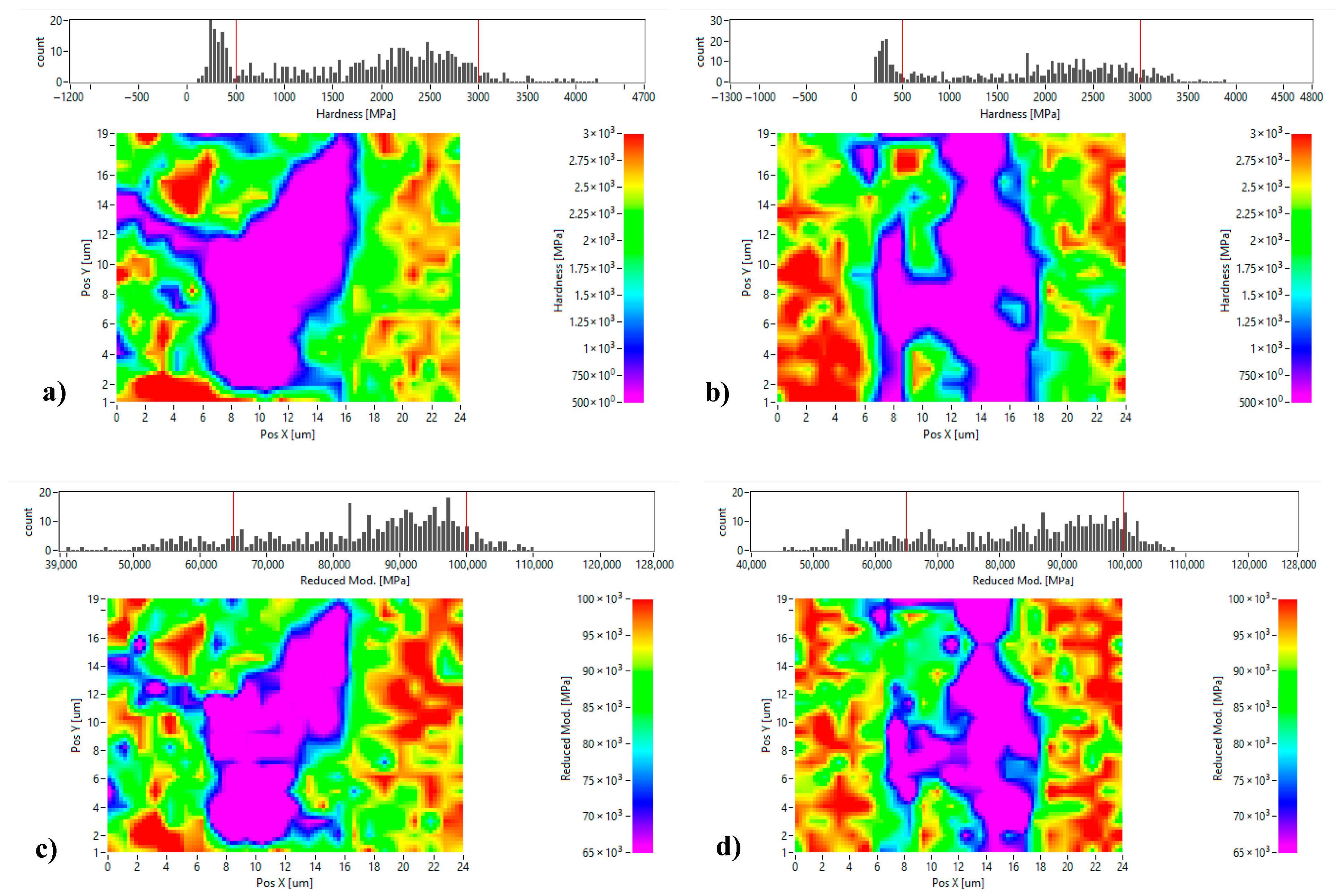

3.6. Nanoindentation

- Both zones (dark-gray and light-gray) exhibit significantly higher values of hardness and elastic modulus on samples obtained by consolidation of milled powders compared to those consolidated from unmilled powders for all same SPS parameters.

- For the SPS-consolidated unmilled powders:

- ○

- In the dark-gray zones (nano-grains), the nanohardness average values are not statistically different.

- ○

- In the light-gray zones (recrystallized grains), the nanohardness average values are statistically different with a confidence index of >99%

- For SPS-consolidated milled powders:

- ○

- In the dark-gray zones (nano-grains), the nanohardness average values are statistically different with a confidence index >99%.

- ○

- In the light-gray zones (recrystallized grains), the nanohardness average value of the SPS 600 °C–50 MPa sample is statistically different with a confidence index >99% in comparison with the other two samples, while the values measured on samples SPS 600 °C–100 MPa and SPS 625 °C–100 MPa are not statistically different.

- The average reduced elastic modulus of both zones (nano-grains or recrystallized grains) is bigger for samples made of milled powders than those made of unmilled powders.

3.7. Microhardness

3.8. Tribological Characterizations

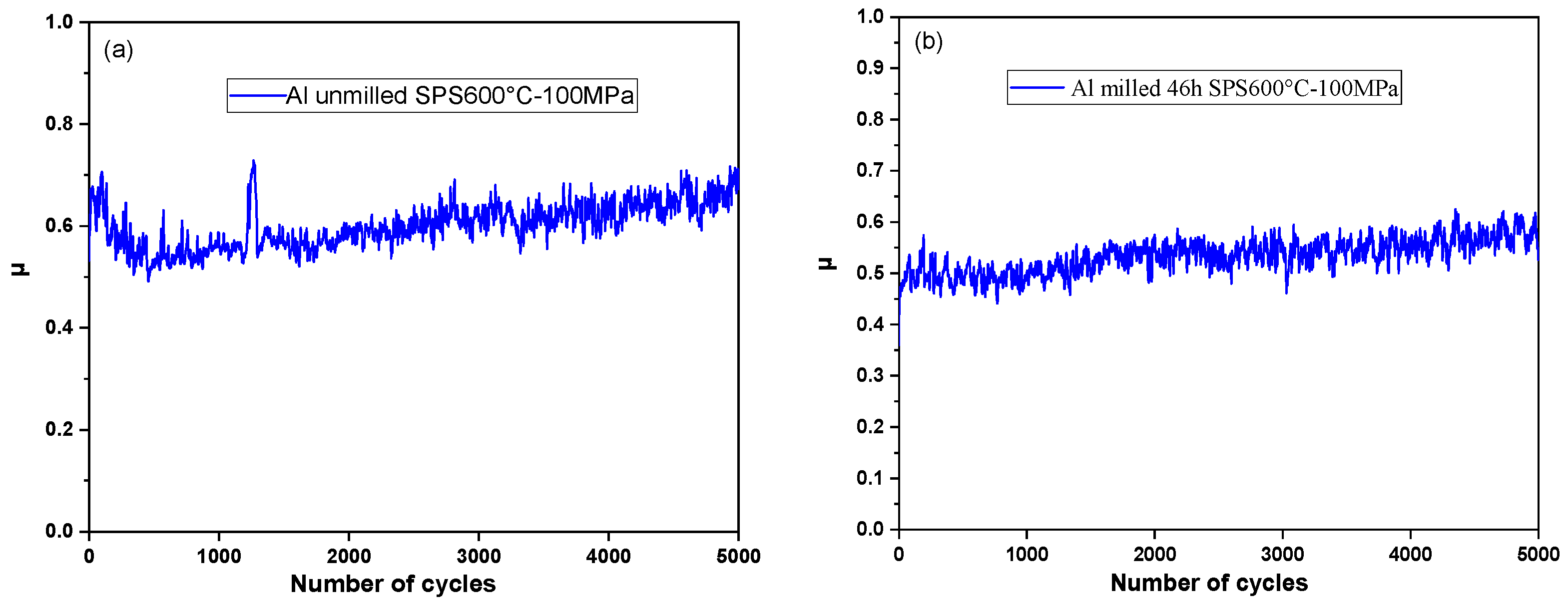

3.8.1. Coefficient of Friction

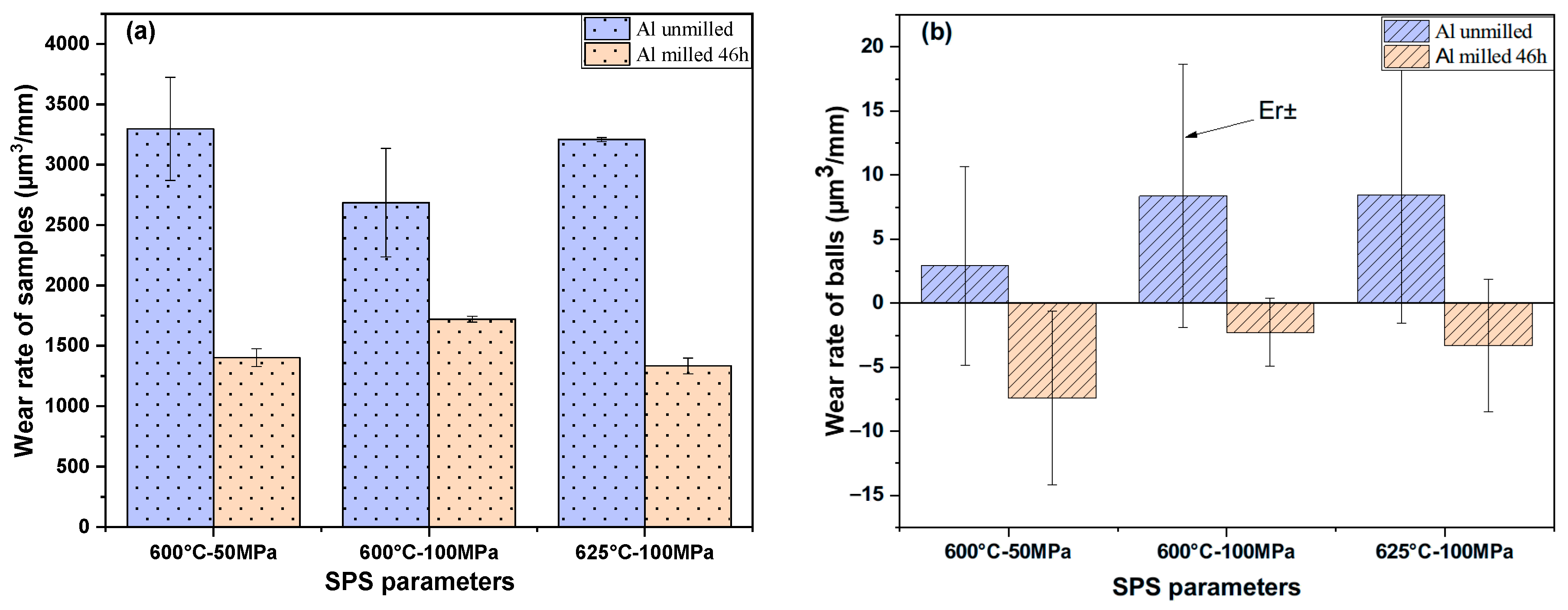

3.8.2. Wear Rate

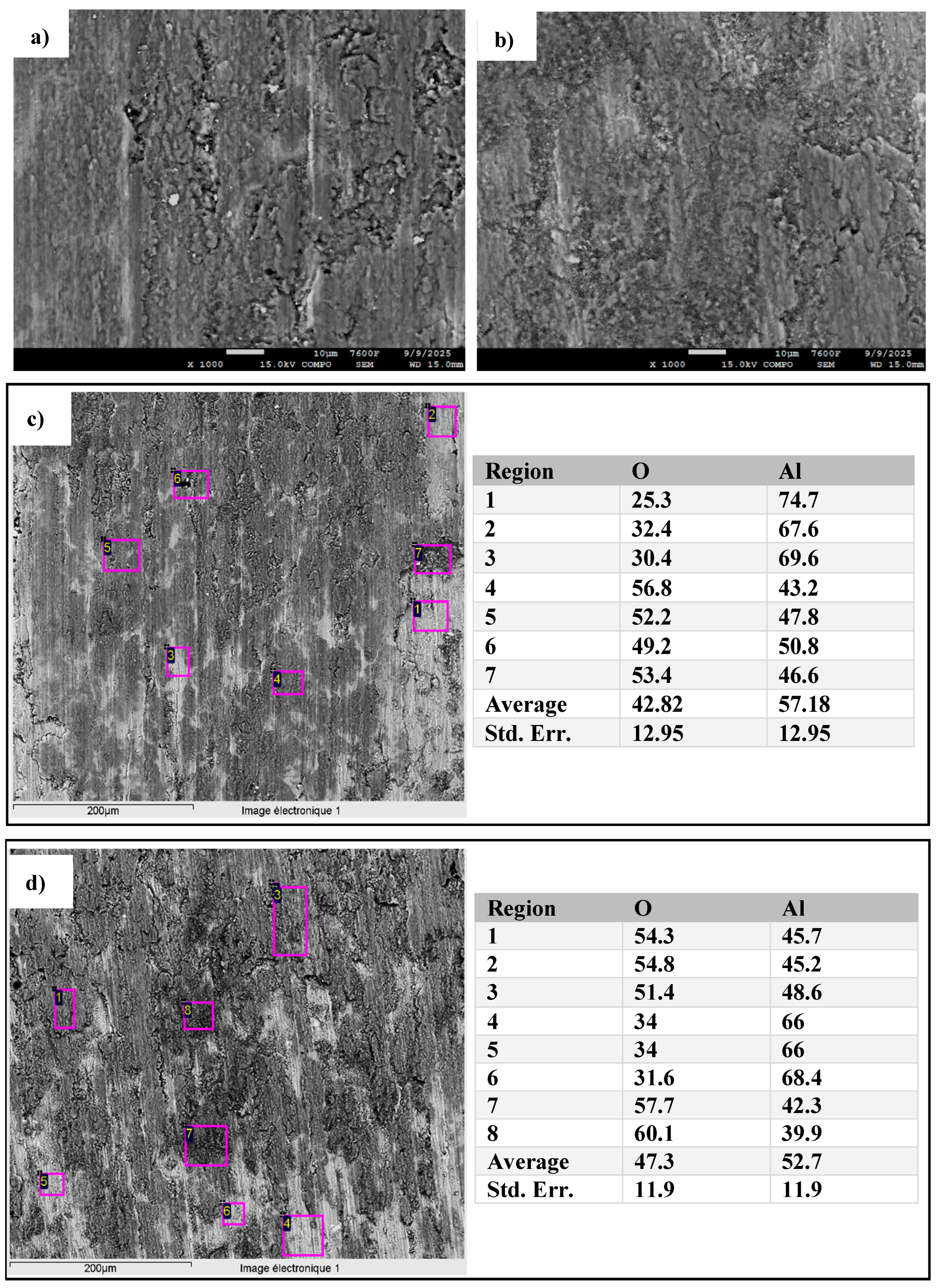

3.8.3. Morphologies of the Worn Surface

4. Conclusions

- In contrast to most studies in the literature where milling is achieved under an inert atmosphere (argon), this work was conducted in air. This particularity promotes the formation of alumina dispersion, which may contribute to the mechanical reinforcement of the consolidated materials.

- High-energy ball milling promoted powder agglomeration and increased grain size distribution while significantly refining crystallite size.

- The milled-aluminum sintered SPS sample achieved full densification (100%) at 600 °C and 100 MPa, which is not the case for the unmilled sample consolidated at these SPS parameters.

- All SPS-consolidated samples made of milled powders exhibited a higher dislocation density compared to the samples made of unmilled powders. This leads to greater hardness, as dislocation interactions restrict plastic deformation.

- Two principal morphologies were identified: small, agglomerated grains forming a hard phase, and recrystallized grains forming a soft phase.

- For the SPS temperature set to 625 °C, the unmilled and milled consolidated samples showed localized melting, whereas the sample consolidated from milled powders developed clusters of aluminum oxides.

- Milling has a measurable effect on improving the wear resistance of the samples, where the coefficient of friction varies from 0.68 for unmilled powders to 0.56 for milled powders after SPS consolidation at 600 °C – 100 MPa. The abrasive friction is minimized in samples made of milled powders.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shaikh, M.B.N.; Aziz, T.; Arif, S.; Ansari, A.H.; Karagiannidis, P.G.; Uddin, M. Effect of sintering techniques on microstructural, mechanical and tribological properties of Al-SiC composites. Surf. Interfaces 2020, 20, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Chen, F.; Cheng, F.; Li, Z.; Pang, G. Corrosion Properties of Pure Aluminum Prepared by Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) Using Different Grain Size of Aluminium Powders as Raw Material. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2020, 15, 9120–9134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwinski, F. Thermal Stability of Aluminum Alloys. Materials 2020, 13, 3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.S.; Zhuang, L.; Bottema, J.; Wittebrood, A.J.; De Smet, P.; Haszler, A.; Vieregge, A. Recent development in aluminium alloys for the automotive industry. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 280, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, B.; Bukvic, M.; Epler, I. Application of aluminum and aluminum alloys in engineering. Appl. Eng. Lett. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2018, 3, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starke, E.A., Jr.; Staley, J.T. Application of modern aluminum alloys to aircraft. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 1996, 32, 131–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonsino, C.M.; Ziese, J. Fatigue strength and applications of cast aluminium alloys with different degrees of porosity. Int. J. Fatigue 1993, 15, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.H.; Xue, P.; Wu, L.H.; Ni, D.R.; Xiao, B.L.; Ma, Z.Y. Achieving an ultra-high strength in a low alloyed Al alloy via a special structural design. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 755, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, C.S.; Cooper, K.P. Nanomechanics of Hall–Petch relationship in nanocrystalline materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2009, 54, 689–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanarayana, C. Mechanical alloying and milling. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2001, 46, 1–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, J.S. Dispersion strengthened superalloys by mechanical alloying. Metall. Trans. 1970, 1, 2943–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanarayana, C.; Ivanov, E.; Boldyrev, V.V. The science and technology of mechanical alloying. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2001, 304–306, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, L.; Lai, M.O.; Zhang, S. Modeling of the mechanical-alloying process. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 1995, 52, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.B.; Babu, B.S.; Jerrin, K.M.A.; Joseph, N.; Jiss, A. Review of Spark Plasma Sintering Process. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 993, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, Z.A.; Anselmi-Tamburini, U.; Ohyanagi, M. The effect of electric field and pressure on the synthesis and consolidation of materials: A review of the spark plasma sintering method. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokita, M. Progress of Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) Method, Systems, Ceramics Applications and Industrialization. Ceramics 2021, 4, 160–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Chen, W.; Fang, S.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, H.; Zhu, D. Alloying behavior and deformation twinning in a CoNiFeCrAl0.6Ti0.4 high entropy alloy processed by spark plasma sintering. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 553, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Oh, H.-C.; An, B.-H.; Kim, H.-D. Ultra-low temperature synthesis of Al4SiC4 powder using spark plasma sintering. Scr. Mater. 2013, 69, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, G.A.; Brochu, M.; Hexemer, R.L.; Donaldson, I.W.; Bishop, D.P. Consolidation of aluminum-based metal matrix composites via spark plasma sintering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 648, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Ohashi, O.; Yamaguchi, N. Sintering behavior of aluminum powder by spark plasma sintering. Trans. Mater. Res. Soc. Jpn. 2002, 27, 743–746. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.-F.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Lu, J.-F.; Korznikov, A.V.; Korznikova, E.; Wang, F.-C. Effect of sintering temperature on microstructures and mechanical properties of spark plasma sintered nanocrystalline aluminum. Mater. Des. 2014, 64, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.S.; Aljebreen, O.S.; Hakeem, A.S.; Laoui, T.; Patel, F.; Ali Baig, M.M. Tribological Behavior of Aluminum Hybrid Nanocomposites Reinforced with Alumina and Graphene Oxide. Materials 2022, 15, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rengifo, S.; Zhang, C.; Harimkar, S.; Boesl, B.; Agarwal, A. Tribological Behavior of Spark Plasma Sintered Aluminum-Graphene Composites at Room and Elevated Temperatures. Technologies 2017, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabandeh-Khorshid, M.; Omrani, E.; Menezes, P.L.; Rohatgi, P.K. Tribological performance of self-lubricating aluminum matrix nanocomposites: Role of graphene nanoplatelets. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2016, 19, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoushtarian Mofrad, M.S.; Borhani, E.; Yousefieh, M.; Aminian, H. Surface morphology and Rietveld refinement characterisation of aluminium/titania nanocomposite produced by atmospheric plasma spraying and accumulative roll bonding. Can. Metall. Q. 2022, 62, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toby, B.H. R factors in Rietveld analysis: How good is good enough? Powder Diffr. 2006, 21, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saville, A.I.; Creuziger, A.; Mitchell, E.B.; Vogel, S.C.; Benzing, J.T.; Klemm-Toole, J.; Clarke, K.D.; Clarke, A.J. MAUD Rietveld Refinement Software for Neutron Diffraction Texture Studies of Single- and Dual-Phase Materials. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 2021, 10, 461–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, S.; Chowdhury, S.G.; Estrin, Y.; Manna, I. Mechanical properties of Al7075 alloy with nano-ceramic oxide dispersion synthesized by mechanical milling and consolidated by equal channel angular pressing. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 548, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nečas, D.; Klapetek, P. Gwyddion: An open-source software for SPM data analysis. Open Phys. 2012, 10, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornuault, P.-H.; Colas, G.; Lenain, A.; Daudin, R.; Gravier, S. On the diversity of accommodation mechanisms in the tribology of Bulk Metallic Glasses. Tribol. Int. 2020, 141, 105957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboor Bagherzadeh, E.; Dopita, M.; Mütze, T.; Peuker, U.A. Morphological and structural studies on Al reinforced by Al2O3 via mechanical alloying. Adv. Powder Technol. 2015, 26, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Saarna, M.; Yoon, S.; Weidenkaff, A.; Leparoux, M. Effect of milling time on dual-nanoparticulate-reinforced aluminum alloy matrix composite materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 590, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salur, E.; Aslan, A.; Kuntoğlu, M.; Acarer, M. Effect of ball milling time on the structural characteristics and mechanical properties of nano-sized Y2O3 particle reinforced aluminum matrix composites produced by powder metallurgy route. Adv. Powder Technol. 2021, 32, 3826–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.K.; Sivaprahasam, D.; Seetharama Raju, K.; Subramanya Sarma, V. Microstructure and mechanical properties of nanocrystalline high strength Al–Mg–Si (AA6061) alloy by high energy ball milling and spark plasma sintering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 527, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi Tousi, S.S.; Rad, R.Y.; Salahi, E.; Mobasherpour, I.; Razavi, M. Production of Al–20 wt.% Al2O3 composite powder using high energy milling. Powder Technol. 2009, 192, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, E.; Bouchonneau, N.; Alves, E.; Alves, K.; Araújo Filho, O.; Mesguich, D.; Chevallier, G.; Laurent, C.; Estournès, C. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AA7075 Aluminum Alloy Fabricated by Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS). Materials 2021, 14, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christudasjustus, J.; Witharamage, C.S.; Walunj, G.; Borkar, T.; Gupta, R.K. The influence of spark plasma sintering temperatures on the microstructure, hardness, and elastic modulus of the nanocrystalline Al-xV alloys produced by high-energy ball milling. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 122, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, H.; Cai, M.; Liu, L.; Zhai, P. The dynamic properties of SiCp/Al composites fabricated by spark plasma sintering with powders prepared by mechanical alloying process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 527, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, J.; Hazotte, A.; Monchoux, J.P.; Bouzy, E. Effect of powder state on spark plasma sintering of TiAl alloys. Intermetallics 2013, 34, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviot, A.; Sallamand, P.; Monchoux, J.P.; Marcelot, C.; Cours, R.; Geoffroy, N.; Jouvard, J.M.; Le Gallet, S. Phase and microstructure formation during reactive spark plasma sintering of AlxCoCrFeNi (x = 0.3 and 1) high entropy alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 32, 3047–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, A.; Ajdelsztajn, L.; Lavernia, E.J. Spark plasma sintering of a nanocrystalline Al-Cu-Mg-Fe-Ni-Sc alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2006, 37, 1343–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.Z.; Zhou, F.; Lavernia, E.J.; He, D.W.; Zhu, Y.T. Deformation twins in nanocrystalline Al. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 83, 5062–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, S.N.; Walley, S.M. The Hall–Petch and inverse Hall–Petch relations and the hardness of nanocrystalline metals. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 2661–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.S.S.; Deoghare, A.B. Effect of microwave sintering on the mechanical characteristics of Al/kaoline/SiC hybrid composite fabricated through powder metallurgy techniques. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 287, 126276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, W. Mechanical alloying and spark plasma sintering of the intermetallic compound Ti50Al50. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 440, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, A.; Alizadeh, A.; Baharvandi, H.R. Dry sliding tribological behavior and mechanical properties of Al2024–5 wt.%B4C nanocomposite produced by mechanical milling and hot extrusion. Mater. Des. 2014, 55, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, F.; Sharifi, H.; Saeri, M.R.; Tayebi, M. Effect of Reinforcement Volume Fraction on the Wear Behavior of Al-SiCp Composites Prepared by Spark Plasma Sintering. Silicon 2018, 10, 2473–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuis, R.L.; Subramanian, C.; Yellup, J.M. Dry sliding wear of aluminium composites—A review. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1997, 57, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Al | Fe | Si | Ti | Zn | V | Ga | Ni | Cu | Mo | Zr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concen-tration | 99.8 at.% | 0.11 at.% | 363 ppm | 120 ppm | 106 ppm | 101 ppm | 64 ppm | 59 ppm | 42 ppm | 18 ppm | 15 ppm |

| Element | Al Unmilled Powders, at. % | Al Powders Milled for 46 h, at. % |

|---|---|---|

| O | 7.0 (±0.6) | 10.8 (±0.9) |

| N | 0.017 (±0.006) | 0.028 (±0.010) |

| Sample | Unmilled (m−2) | Milled for 46 h (m−2) |

|---|---|---|

| Powders | ||

| SPS600 °C–50 MPa | ||

| SPS600 °C–100 MPa | ||

| SPS625 °C–100 MPa |

| Element. | Al Unmilled Powders SPS600 °C–100 MPa, at. % | Al Milled for 46 h SPS600 °C–100 MPa, at. % |

|---|---|---|

| O | 7.4 (±0.6) | 9.9 (±0.8) |

| N | 0.007 (±0.003) | 0.033 (±0.004) |

| Sample | Relative Density (%) |

|---|---|

| Al unmilled SPS 550 °C–50 MPa | 82.1 (±0.9) |

| Al unmilled SPS 600 °C–50 MPa | 95.4 (±0.9) |

| Al unmilled SPS 600 °C–100 MPa | 98.0 (±0.6) |

| Al unmilled SPS 625 °C–100 MPa | 100 (±0.5) |

| Al milled 46 h SPS 550 °C–50 MPa | 81.6 (±0.5) |

| Al milled 46 h SPS 600 °C–50 MPa | 95.5 (±0.4) |

| Al milled 46 h SPS 600 °C–100 MPa | 100 (±0.9) |

| Al milled 46 h SPS 625 °C–100 MPa | 98.7 (±0.6) |

| Samples | Dark Gray Phase (MPa) | Light Gray Phase (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| Al unmilled SPS 600 °C–50 MPa | 2634 (±109) | 150 (±29) |

| Al unmilled SPS 600 °C–100 MPa | 2635 (±130) | 380 (±60) |

| Al unmilled SPS 625 °C–100 MPa | 2637 (±97) | 480 (±28) |

| Al milled 46 h SPS 600 °C–50 MPa | 2740 (±85) | 400 (±65) |

| Al milled 46 h SPS 600 °C–100 MPa | 3415 (±175) | 662 (±78) |

| Al milled 46 h SPS 625 °C–100 MPa | 4027 (±180) | 630 (±73) |

| Samples | Dark Gray Phase (MPa) | Light Gray Phase (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| Al unmilled SPS 600 °C–50 MPa | 93.5 (±5) | 28.5 (±9) |

| Al unmilled SPS 600 °C–100 MPa | 85 (±5) | 61 (±8) |

| Al unmilled SPS 625 °C–100 MPa | 95 (±5) | 71 (±3) |

| Al milled 46 h SPS 600 °C–50 MPa | 90 (±2) | 65 (±5) |

| Al milled 46 h SPS 600 °C–100 MPa | 101 (±4) | 77 (±3) |

| Al milled 46 h SPS 625 °C–100 MPa | 115 (±7) | 76 (±4) |

| Samples | |

|---|---|

| Al unmilled SPS 600 °C–50 MPa | 0.65 (±0.04) |

| Al unmilled SPS 600 °C–100 MPa | 0.67 (±0.14) |

| Al unmilled SPS 625 °C–100 MPa | 0.88 (±0.061) |

| Al milled 46 h SPS 600 °C–50 MPa | 0.58 (±0.16) |

| Al milled 46 h SPS 600 °C–100 MPa | 0.56 (±0.03) |

| Al milled 46 h SPS 625 °C–50 MPa | 0.63 (±0.18) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ammari, H.; Le Gallet, S.; Cornuault, P.-H.; Herbst, F.; Geoffroy, N.; Chemingui, M.; Optasanu, V. Influence of Spark Plasma Sintering Parameters on the Microstructure, Mechanical and Tribological Characteristics of Air-Milled Aluminum. Materials 2025, 18, 5652. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245652

Ammari H, Le Gallet S, Cornuault P-H, Herbst F, Geoffroy N, Chemingui M, Optasanu V. Influence of Spark Plasma Sintering Parameters on the Microstructure, Mechanical and Tribological Characteristics of Air-Milled Aluminum. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5652. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245652

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmmari, Hanen, Sophie Le Gallet, Pierre-Henri Cornuault, Frédéric Herbst, Nicolas Geoffroy, Mahmoud Chemingui, and Virgil Optasanu. 2025. "Influence of Spark Plasma Sintering Parameters on the Microstructure, Mechanical and Tribological Characteristics of Air-Milled Aluminum" Materials 18, no. 24: 5652. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245652

APA StyleAmmari, H., Le Gallet, S., Cornuault, P.-H., Herbst, F., Geoffroy, N., Chemingui, M., & Optasanu, V. (2025). Influence of Spark Plasma Sintering Parameters on the Microstructure, Mechanical and Tribological Characteristics of Air-Milled Aluminum. Materials, 18(24), 5652. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245652