Molybdenum Nitride and Oxide Layers Grown on Mo Foil for Supercapacitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

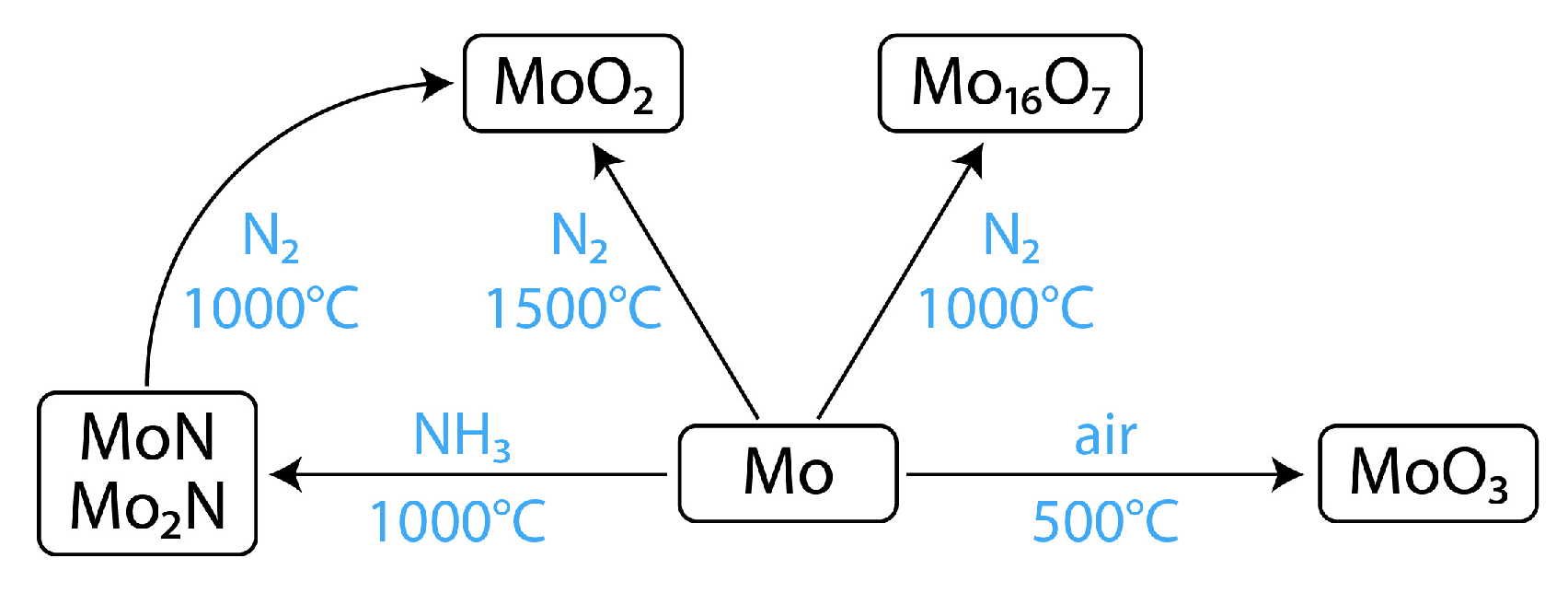

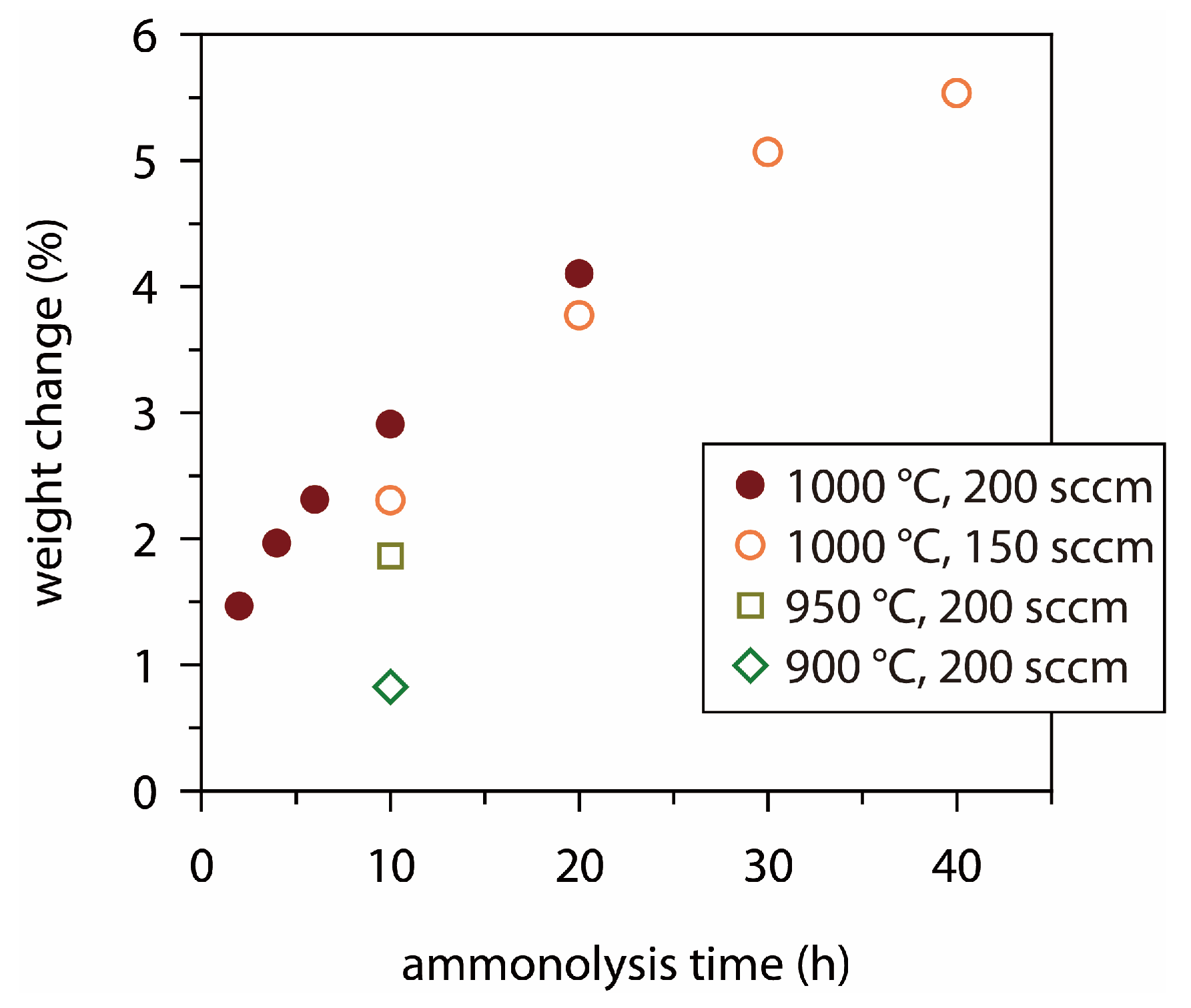

3.1. Surface Modification of Mo Foil by Heat Treatment

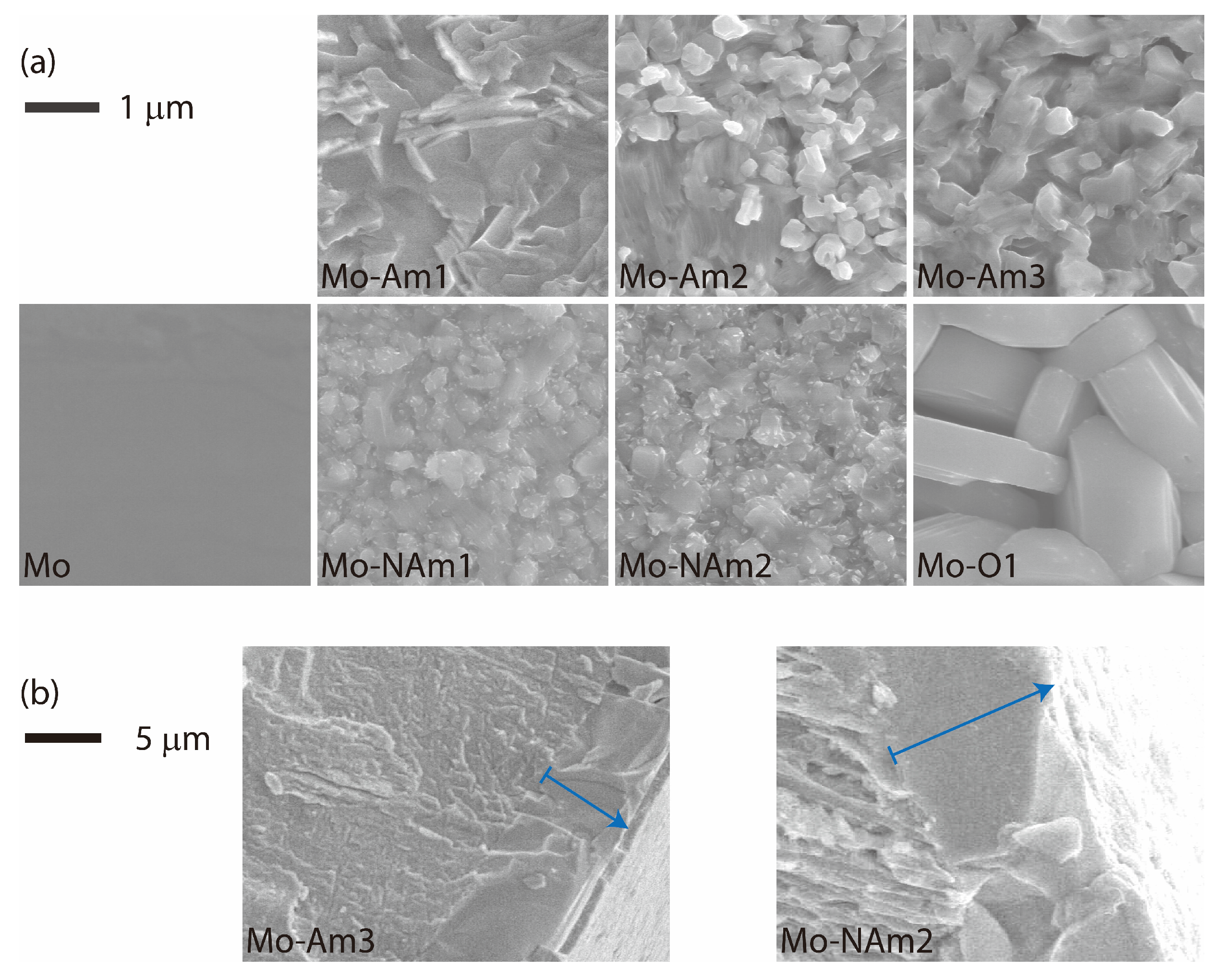

3.2. SEM, UV-Vis, and XPS

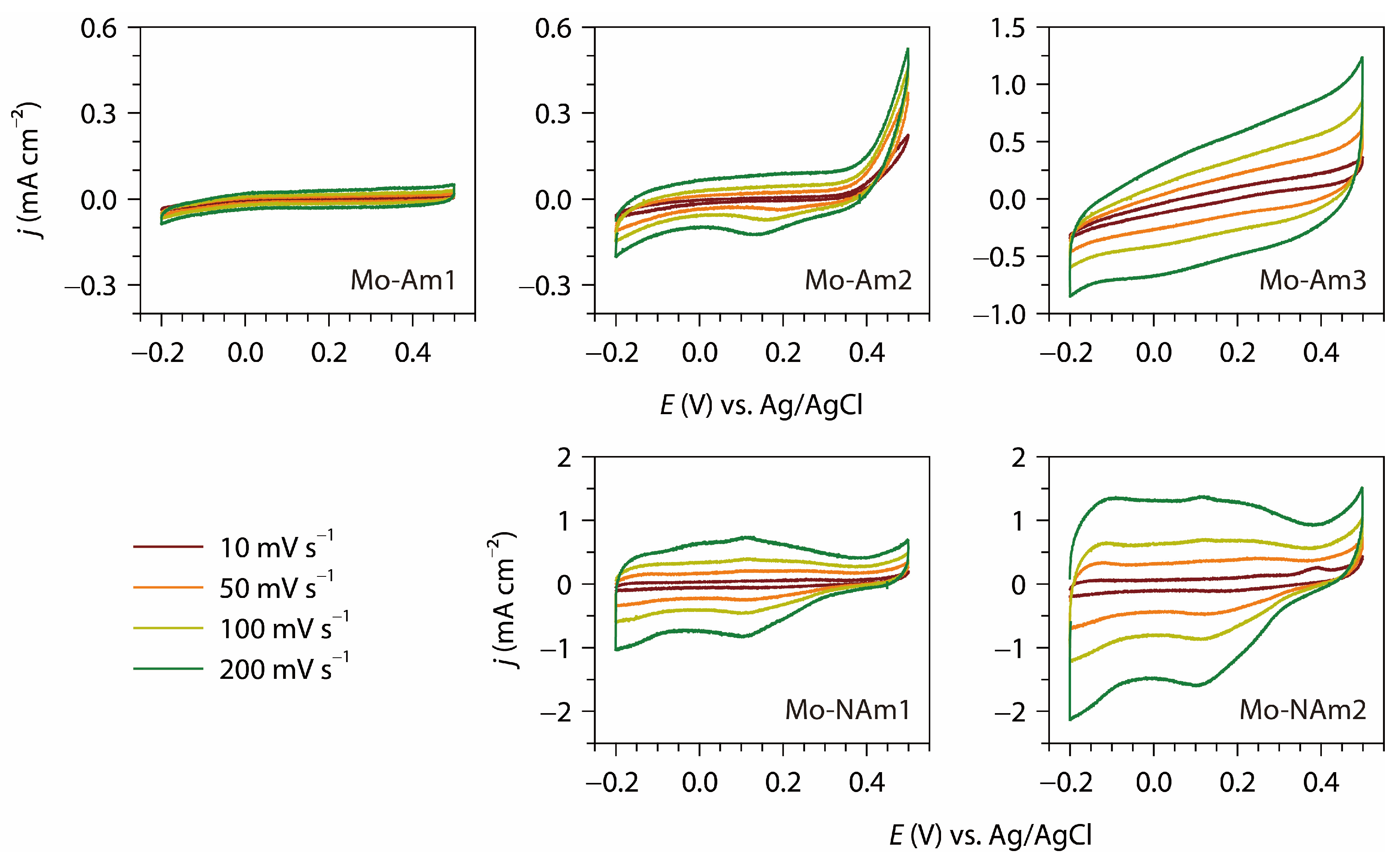

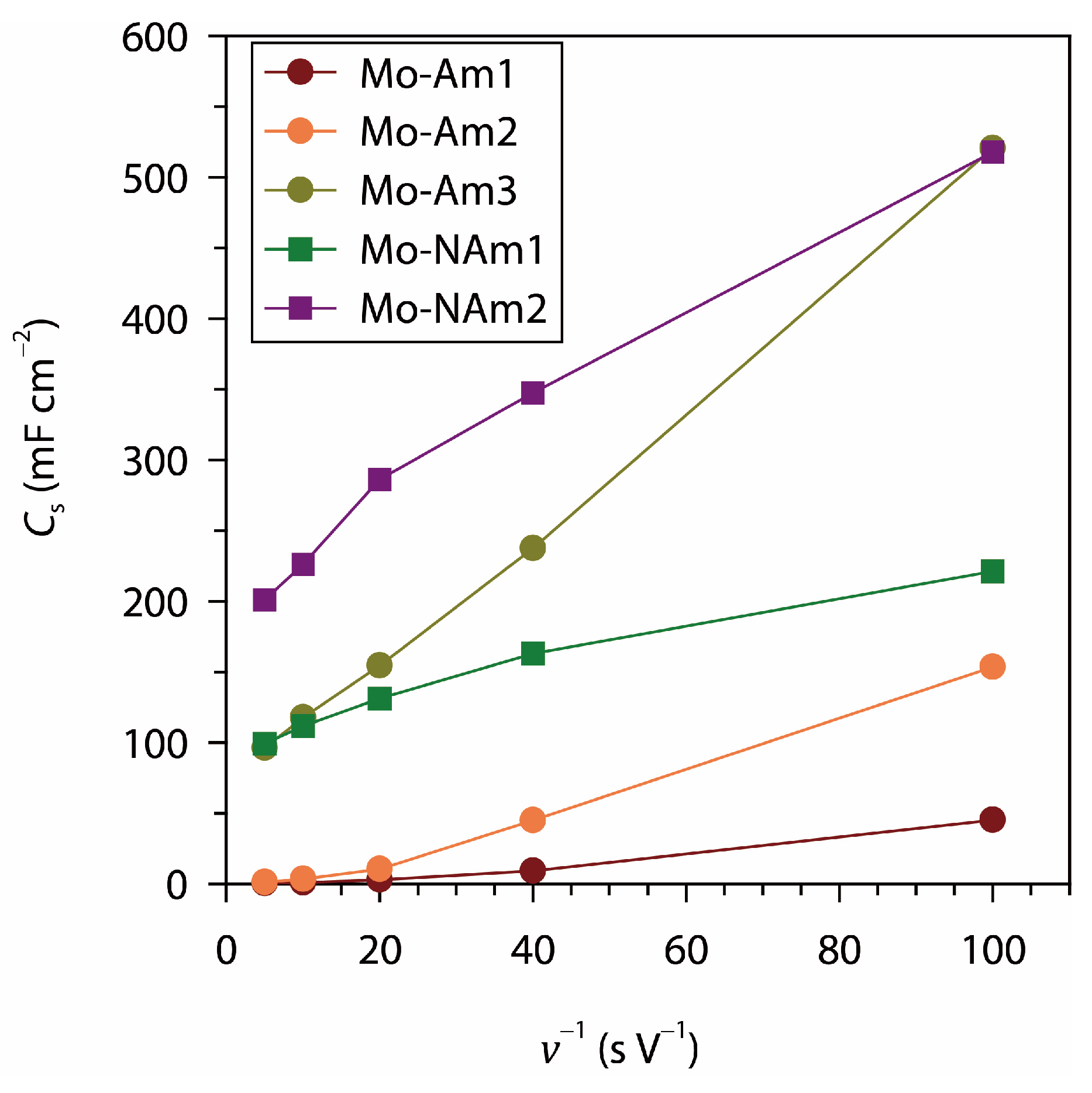

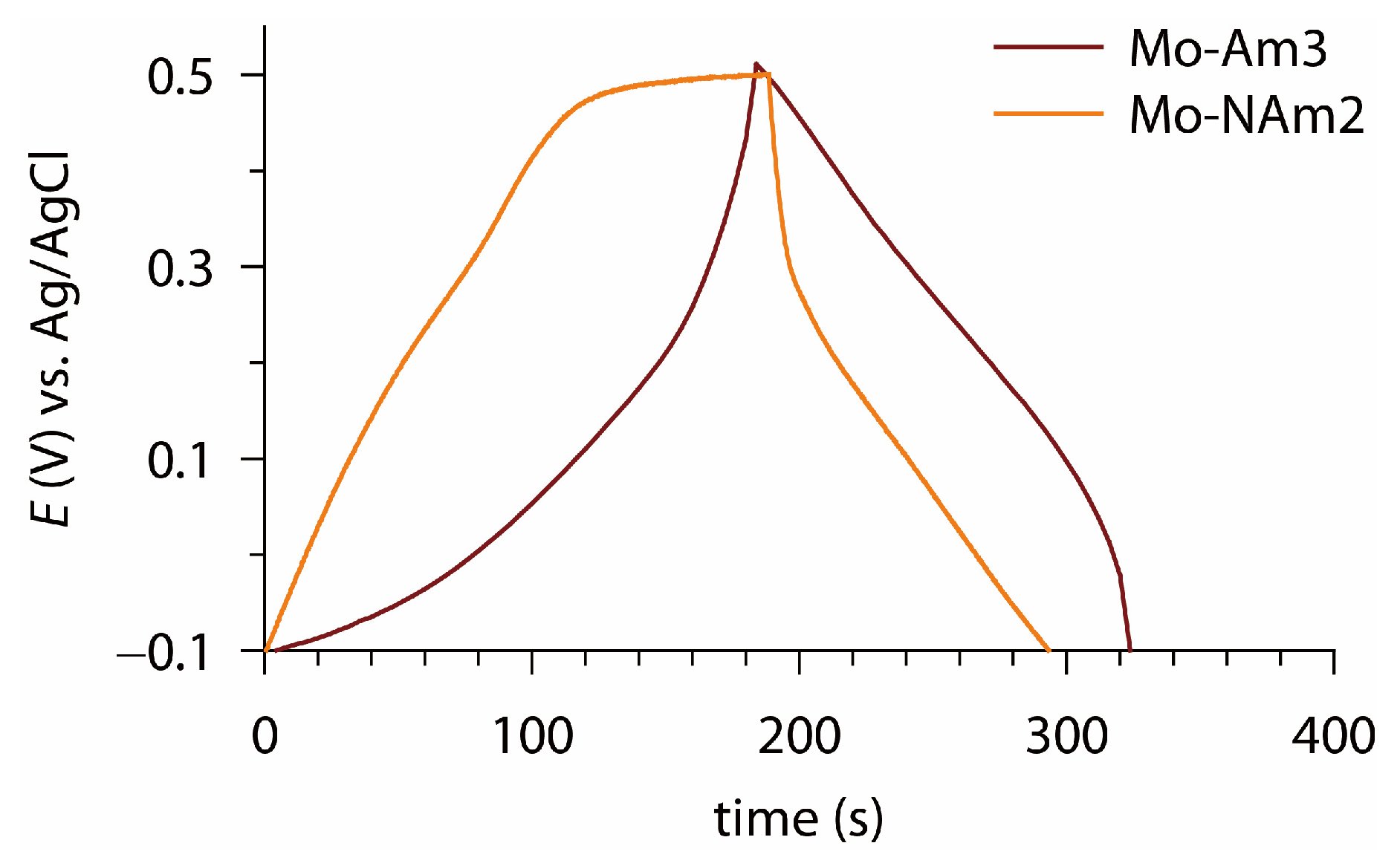

3.3. Electrochemical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kandhasamy, M.; Duvaragan, B.K.; Kamaraj, S.; Shanmugam, G. An overview on classification of energy storage systems. In Materials for Boosting Energy Storage. Volume 2: Advances in Sustainable Energy Technologies; Kumar, S.S., Sharma, P., Kumar, T., Kumar, V., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Ali, A.; D’Angola, A. A review of renewable energy communities: Concepts, scope, progress, challenges, and recommendations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najib, S.; Erdem, E. Current progress achieved in novel materials for supercapacitor electrodes: Mini review. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 2817–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonam; Sharma, K.; Arora, A.; Tripathi, S.K. Review of supercapacitors: Materials and devices. J. Energy Storage 2019, 21, 801–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Goikolea, E.; Barrena, J.A.; Mysyk, R. Review on supercapacitors: Technologies and materials. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 1189–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lee, P.S. Electrochemical supercapacitors: From mechanism understanding to multifunctional applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2003311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouzandeh, P.; Kumaravel, V.; Pillai, S.C. Electrode materials for supercapacitors: A review of recent advances. Catalysts 2020, 10, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksoud, M.I.A.A.; Fahim, R.A.; Shalan, A.E.; Elkodous, M.A.; Olojede, S.O.; Osman, A.I.; Farrell, C.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Awed, A.S.; Ashour, A.H.; et al. Advanced materials and technologies for supercapacitors used in energy conversion and storage: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 375–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béguin, F.; Presser, V.; Balducci, A.; Frackowiak, E. Carbons and electrolytes for advanced supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 2219–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro-Prado, I.; Salinas-Torres, D.; Ruiz-Rosas, R.; Morallón, E.; Cazorla-Amorós, D. Design of activated carbon/activated carbon asymmetric capacitors. Front. Mater. 2016, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnan, M.; Raj, A.G.K.; Subramani, K.; Santhoshkumara, S.; Sathish, M. The fascinating supercapacitive performance of activated carbon electrodes with enhanced energy density in multifarious electrolytes. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 3029–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, N.A.M.; Mahmoud, M.S.; Moustafa, H.M. Comparing specific capacitance in rice husk-derived activated carbon through phosphoric acid and potassium hydroxide activation order variations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Su, Y. Recent progress of transition metal-based oxide composite electrode materials in supercapacitor. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2025, 9, 2400578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, U.N.; Ghosh, S.; Thomas, T. Metal oxynitrides as promising electrode materials for supercapacitor applications. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 1255–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.; Thomas, T. Recent advances and prospects of metal oxynitrides for supercapacitor. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2022, 68, 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, D.; Ge, Z.; Pan, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Mitsuzaki, N.; Jia, S.; Chen, Z. Recent advances in transition metal sulfide-based electrode materials for supercapacitors. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 8314–8326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lin, H.; Zhai, L.; Nie, M.; Zhou, J.; Zhuo, S. Enhanced supercapacitor performance based on 3D porous graphene with MoO2 nanoparticles. J. Mater. Res. 2017, 32, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, E.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Z.; Shao, M.; Deng, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, X. Facile synthesis of MoO2 nanoparticles as high performance supercapacitor electrodes and photocatalysts. Ceram. Inter. 2016, 42, 2198–2203. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Lee, C.W.; Yoon, S. Development of an ordered mesoporous carbon/MoO2 nanocomposite for high performance supercapacitor electrode. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2011, 14, A157–A160. [Google Scholar]

- Riaz, M.B.; Hussain, D.; Awan, S.U.; Rizwan, S.; Zainab, S.; Shah, S.A. 2-Dimensional Ti3C2Tx/NaF nano-composites as electrode materials for hybrid battery-supercapacitor applications. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi-Qashqay, S.; Zamani-Meymian, M.R.; Maleki, A. A simple method of fabrication hybrid electrodes for supercapacitors. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abebe, E.M.; Ujihara, M. Simultaneous electrodeposition of ternary metal oxide nanocomposites for high-efficiency supercapacitor applications. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 17161–17174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Park, J.W.; Lee, D.W.; Baughman, R.H.; Kim, S.J. Electrodeposition of α-MnO2/γ-MnO2 on carbon nanotube for yarn supercapacitor. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobade, R.G.; Dabke, N.B.; Shaikh, S.F.; Al-Enizi, A.M.; Pandit, B.; Lokhande, B.J.; Ambare, R.C. Influence of deposition potential on electrodeposited bismuth-copper oxide electrodes for asymmetric supercapacitor. Batter. Supercaps 2024, 7, e202400163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanapongpisit, N.; Wongprasod, S.; Laohana, P.; Sonsupap, S.; Khajonrit, J.; Musikajaroen, S.; Wongpratat, U.; Yotburut, B.; Maensiri, S.; Meevasana, W.; et al. Enhancing activated carbon supercapacitor electrodes using sputtered Cu-doped BiFeO3 thin films. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.H.; Choi, D.J.; Kim, H.; Cho, W.I.; Yoon, Y.S. Thin film supercapacitors using a sputtered RuO2 electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2001, 148, A275–A278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z. MoOx thin films deposited by magnetron sputtering as an anode for aqueous micro-supercapacitors. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2013, 14, 065005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhao, T.; Chen, Q.; Li, P.; Wang, K.; Zhong, M.; Wei, J.; Wu, D.; Wei, B.; Zhu, H. Flexible all solid-state supercapacitors based on chemical vapor deposition derived graphene fibers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 17752–17757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bláha, M.; Bouša, M.; Valeš, V.; Frank, O.; Kalbáč, M. Two-dimensional CVD-graphene/polyaniline supercapacitors: Synthesis strategy and electrochemical operation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 34686–34695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Su, J.; Wang, X. Atomic layer deposition in the development of supercapacitor and lithium-ion battery devices. Carbon 2021, 179, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y.-I. Growth of oxide and nitride layers on titanium foil and their electrochemical properties. Materials 2025, 18, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas-Lizana, F.; Gomez-Quero, S.; Perret, N.; Kiwi-Minsker, L.; Keane, M.A. β-Molybdenum nitride: Synthesis mechanism and catalytic response in the gas phase hydrogenation of p-chloronitrobenzene. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2011, 1, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, C.L.; Kawashima, T.; McMillan, P.F.; Machon, D.; Shebanova, O.; Daisenberger, D.; Soignard, E.; Takayama-Muromachi, E.; Chapon, L.C. Crystal structure and high-pressure properties of γ-Mo2N determined by neutron powder diffraction and X-ray diffraction. J. Solid State Chem. 2006, 179, 1762–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganin, A.Y.; Kienle, L.; Vajenine, G.V. Synthesis and characterisation of hexagonal molybdenum nitrides. J. Solid State Chem. 2006, 179, 2339–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demura, M.; Nagao, M.; Lee, C.-H.; Goto, Y.; Nambu, Y.; Avdeev, M.; Masubuchi, M.; Mitsudome, T.; Sun, W.; Tadanaga, K.; et al. Nitrogen-rich molybdenum nitride synthesized in a crucible under air. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 4989–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, M.; Biswal, A.; Beura, D.P.; Mohanty, D.; Mishra, T.T.; Mishra, S.; Roy, D.; Behera, J.N. Review on molybdenum-based negative electrodes for high-performance supercapacitors. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 16715–16736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, D.; Lin, R.; Jiang, K.; Yu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yan, H.; Mai, W. High-performance porous molybdenum oxynitride based fiber supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 29699–29706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palraj, J.; Arulraj, A.; M, S.; Therese, H.A. Rapid and stable energy storage using MoN/Mo2N composite electrodes. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2024, 19, 100579. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.; Zhao, H.; Javed, M.S.; Siyal, S.H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Ahmad, A.; Hussain, I.; Habila, M.A.; Han, W. Biodegradable MoNx@Mo-foil electrodes for human-friendly supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 5749–5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, K.; Yu, L. One-step hydrothermal synthesis of MoO2/MoS2 nanocomposites as high-performance electrode material for supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 49909–49918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, W.; Shen, R.; Yang, R.; Yu, G.; Guo, X.; Peng, L.; Ding, W. Partially nitrided molybdenum trioxide with promoted performance as an anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 699–704. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Mei, Y.; Huang, Y. Nanostructured Mo-based electrode materials for electrochemical energy storage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 2376–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaf, Z.N.; Miran, H.A.; Jiang, Z.-T.; Altarawneh, M. Molybdenum nitrides from structures to industrial applications. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2023, 39, 329–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safeer, M.; Sathiskumar, C.; John, N.S. Metallic MoO2 as a highly selective catalyst for electrochemical nitrogen fixation to ammonia under ambient conditions. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202203344. [Google Scholar]

- Kreider, M.E.; Stevens, M.B.; Liu, Y.; Patel, A.M.; Statt, M.J.; Gibbons, B.M.; Gallo, A.; Ben-Naim, M.; Mehta, A.; Davis, R.C.; et al. Nitride or oxynitride? Elucidating the composition-activity relationships in molybdenum nitride electrocatalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 2946–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Neuefeind, J.C.; Adzic, R.R.; Khalifah, P.G. Molybdenum nitrides as oxygen reduction reaction catalysts: Structural and electrochemical studies. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 2128–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Zhai, S.; Wang, S.; Ru, Q.; Hou, X.; Hui, K.S.; Hui, K.N.; Chen, F. Recent progress in binder-free electrodes synthesis for electrochemical energy storage application. Batter. Supercaps 2021, 4, 860–880. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wei, X.; Chen, L.; Shi, J.; He, M. Nickel-molybdenum nitride nanoplate electrocatalysts for concurrent electrolytic hydrogen and formate productions. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, F.; Ma, H.; Shen, L.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, T.; Ma, J.; Geng, X.; Kiran, A.; Zhu, N. Wearable helical molybdenum nitride supercapacitors for self-powered healthcare smartsensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 29780–29787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.G.-M.; Pimlott, J.L.; Down, M.P.; Rowley-Neale, S.J.; Banks, C.E. MoO2 nanowire electrochemically decorated graphene additively manufactured supercapacitor platforms. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Du, H.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Zhang, X. Microwave synthesis of MoS2/MoO2@CNT nanocomposites with excellent cycling stability for supercapacitor electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 9545–9555. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bail, A. Whole powder pattern decomposition methods and applications: A retrospection. Powder Diffr. 2005, 20, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.C.; von Dreele, R.B. General Structure Analysis System; Los Alamos National Laboratory: Los Alamos, NM, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Toby, B.H. EXPGUI, a graphical user interface for GSAS. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2001, 34, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubelka, P.; Munk, F. Ein beitrag zur optic der farbanstriche. Z. Tech. Phys. 1931, 12, 593–601. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, N.; Ma, X.; Su, Y.; Jiang, P.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, D. TiN thin film electrodes on textured silicon substrates for supercapacitors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, H802–H809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, G. Röntgenuntersuchungen über molybdän- und wolframnitride. Z. Phys. Chem. B 1930, 7, 339–362. [Google Scholar]

- Lengauer, W.J. Formation of molybdenum nitrides by ammonia nitridation of MoCl5. J. Cryst. Growth 1988, 87, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, C.L.; McMillan, P.F.; Soignard, E.; Leinenweber, K. Determination of the crystal structure of δ-MoN by neutron diffraction. J. Solid State Chem. 2004, 177, 1488–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Range, K.J. High pressure synthesis of molybdenum nitride MoN. J. Alloys Compd. 2000, 296, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilića, A.; Cardenasa, L.; Mesbaha, A.; Bonjourb, E.; Jameb, P.; Michelc, C.; Loridanta, S.; Perret, N. Guidelines for the synthesis of molybdenum nitride: Understanding the mechanism and the control of crystallographic phase and nitrogen content. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 924, 166576. [Google Scholar]

- Saur, E.J.; Schechinger, H.D.; Rinderer, L. Preparation and superconducting properties of MoN and MoC in form of wires. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1981, MAG-17, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Karam, R.; Ward, R. The preparation of β-molybdenum nitride. Inorg. Chem. 1970, 9, 1385–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, B.G. A refinement of the crystal structure of molybdenum dioxide. Acta Chem. Scand. 1967, 21, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, D.O.; Watson, G.W.; Payne, D.J.; Atkinson, G.R.; Egdell, R.G.; Law, D.S.L. Theoretical and experimental study of the electronic structures of MoO3 and MoO2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 4636–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulder, J.F.; Stickle, W.F.; Sobol, P.E.; Bomben, K.D. Handbook of X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy; Perkin-Elmer: Eden Prairie, MN, USA, 1992; pp. 112–113. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z. Novel [111] oriented γ-Mo2N thin films deposited by magnetron sputtering as an anode for aqueous micro-supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 245, 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Huang, K.; Tang, H.L.; Lei, M. Porous and single-crystalline-like molybdenum nitride nanobelts as a non-noble electrocatalyst for alkaline fuel cells and electrode materials for supercapacitors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 996–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, A.; Shen, Y.; Cui, T.; Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Zhan, R.; Tang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Deng, S. One-step synthesis of heterostructured Mo@MoO2 nanosheets for high-performance supercapacitors with long cycling life and high rate capability. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giardi, R.; Porro, S.; Topuria, T.; Thompson, L.; Pirri, C.F.; Kim, H.-C. One-pot synthesis of graphene-molybdenum oxide hybrids and their application to supercapacitor electrodes. Appl. Mater. Today 2015, 1, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Heat Treatment | XRD Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Mo-Am1 | (NH3) 1000 °C, 2 h | δ-MoN, γ-Mo2N |

| Mo-Am2 | (NH3) 1000 °C, 10 h | δ-MoN, γ-Mo2N |

| Mo-Am3 | (NH3) 1000 °C, 20 h | δ-MoN, γ-Mo2N |

| Mo-N1 | (N2) 1000 °C, 10 h | Mo16N7 |

| Mo-N2 | (N2) 1500 °C, 2 h | MoO2 |

| Mo-NAm1 | (NH3) 1000 °C, 10 h/(N2) 1000 °C, 2 h | MoO2 |

| Mo-NAm2 | (NH3) 1000 °C, 20 h/(N2) 1000 °C, 2 h | MoO2 |

| Mo-O1 | (air) 500 °C, 0.5 h | α-MoO3 |

| Sample | δ-MoN (Hexagonal, Z = 8) | γ-Mo2N (Cubic, Z = 2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a (Å) | c (Å) | V (Å3) | a (Å) | V (Å3) | |

| Mo-Am1 | 5.7412(1) | 5.625(1) | 160.56(6) | 4.16795(5) | 72.405(2) |

| Mo-Am2 | 5.738(1) | 5.622(1) | 160.28(6) | 4.1708(4) | 72.55(2) |

| Mo-Am3 | 5.738(2) | 5.622(1) | 160.29(8) | 4.1705(4) | 72.54(2) |

| Literature | 5.7356 | 5.6281 | 160.34 | 4.1616 | 72.07 |

| Sample | MoO2 (Monoclinic, Z = 4) | ||||

| a (Å) | b (Å) | c (Å) | β (°) | V(Å3) | |

| Mo-NAm1 | 5.6119(4) | 4.8559(4) | 5.6267(4) | 120.935 | 131.52(2) |

| Mo-NAm2 | 5.6121(5) | 4.8557(6) | 5.6274(5) | 120.944 | 131.53(2) |

| Literature | 5.6109 | 4.8562 | 5.6285 | 120.95 | 131.52 |

| Electrode | Cs | Test Condition | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| MoN/Mo2N composite | 306.7 F g−1 | GCD (1 A g−1) | [38] |

| MoN@Mo | 10 F cm−2 | GCD (1 A g−1) | [39] |

| MoN on N-doped carbon cloth | 467.6 mF cm−2 | GCD (5 mA cm−2) | [49] |

| Mo2N (dense film) | 55 mF cm−2 | CV (5 mV s−1) | [67] |

| Mo2N (nanobelts) | 160 F g−1 | CV (5 mV s−1) | [68] |

| Mo-Am3 | 521 mF cm−2 | CV (10 mV s−1) | 1 |

| MoON/TiN | 736.6 mF cm−2 | CV (10 mV s−1) | [37] |

| Mo@MoO2 | 205.1 F g−1 | GCD (1 A g−1) | [69] |

| MoO2/graphene | 140 F g−1 | GCD (1 A g−1) | [70] |

| Mo-NAm2 | 518 mF cm−2 | CV (10 mV s−1) | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, D.H.; Kim, Y.-I. Molybdenum Nitride and Oxide Layers Grown on Mo Foil for Supercapacitors. Materials 2025, 18, 5649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245649

Lim DH, Kim Y-I. Molybdenum Nitride and Oxide Layers Grown on Mo Foil for Supercapacitors. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245649

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Dong Hyun, and Young-Il Kim. 2025. "Molybdenum Nitride and Oxide Layers Grown on Mo Foil for Supercapacitors" Materials 18, no. 24: 5649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245649

APA StyleLim, D. H., & Kim, Y.-I. (2025). Molybdenum Nitride and Oxide Layers Grown on Mo Foil for Supercapacitors. Materials, 18(24), 5649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245649