Experimental Investigation on Factors Influencing the Early-Age Strength of Geopolymer Paste, Mortar, and Concrete

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

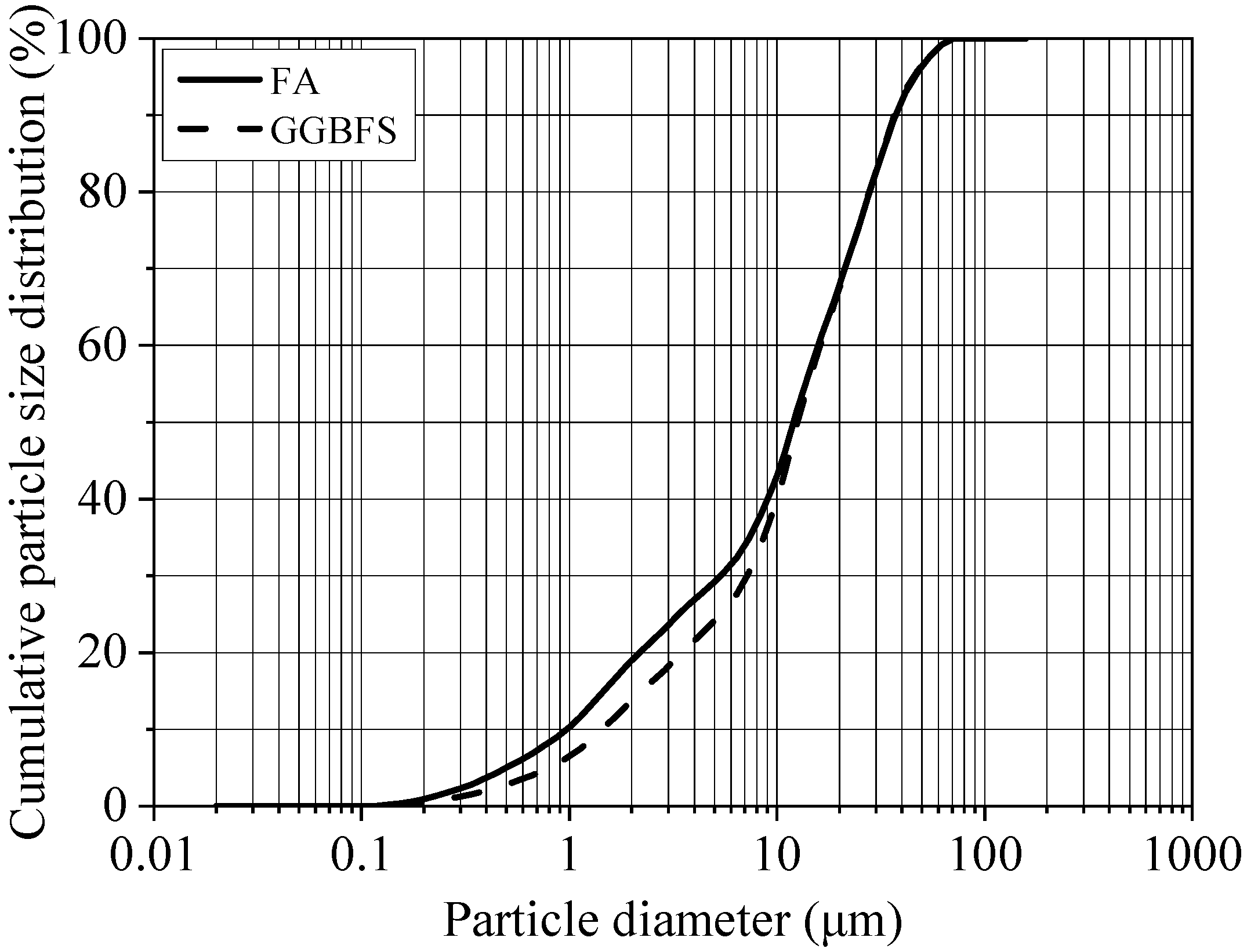

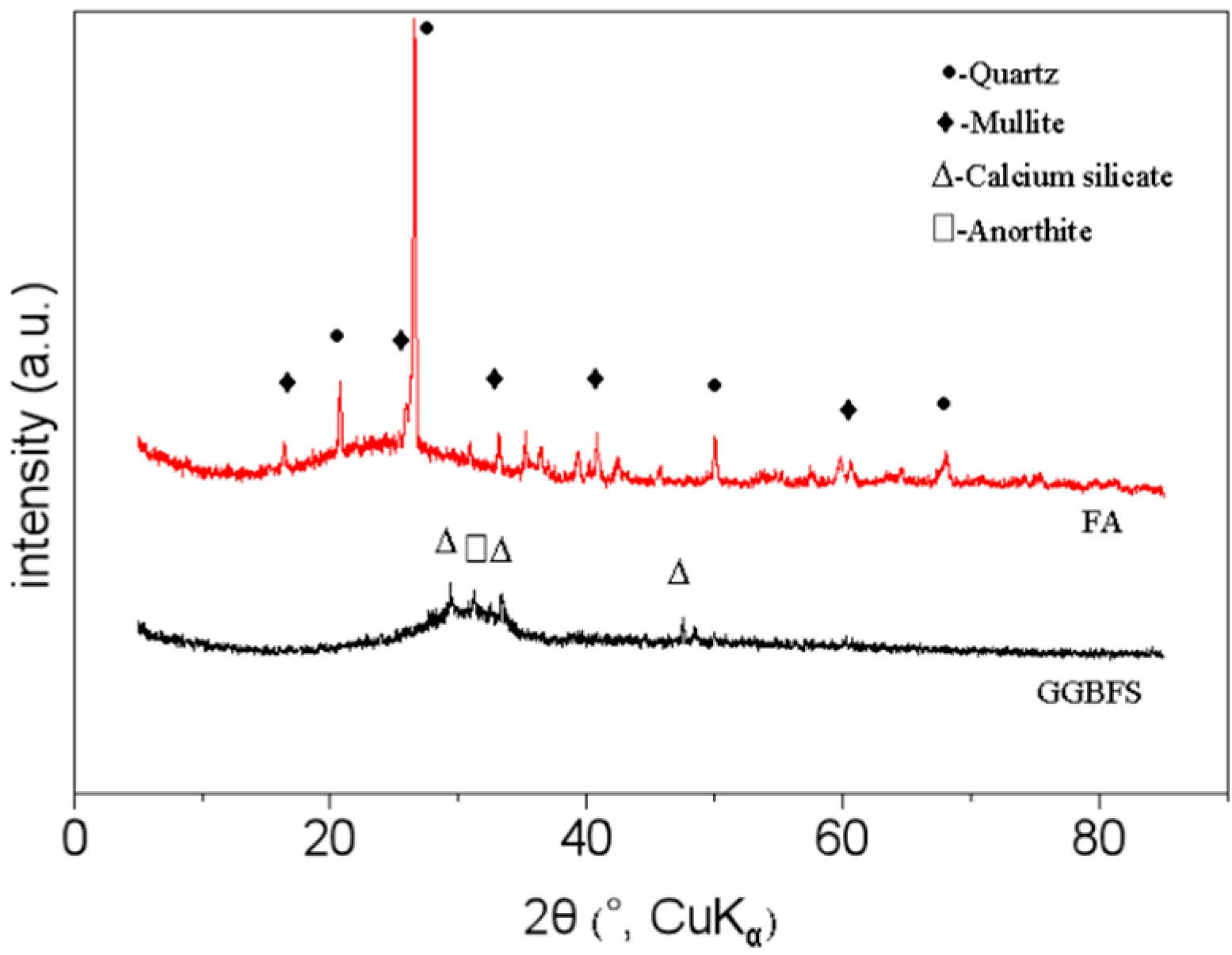

2.1. Source Materials

2.2. Aggregates and Alkaline Activator

2.3. Specimen Preparation and Curing

2.4. Mix Proportion and Testing Methods

2.5. Microstructural Characterization

2.6. Grey Relational Analysis

- (1)

- Determination of sequences

- (2)

- Calculate the mean value of each sequence

- (3)

- Normalize each sequence to obtain dimensionless standardized data sequences x′(k)

- (4)

- Calculate the absolute difference (Δci(k)) between the elements of each comparison child sequence (x′0(k)) and the corresponding elements of the parent sequence (x′i(k))

- (5)

- Determine the maximum (M) and minimum (q) of the absolute differences

- (6)

- Calculate the correlation coefficient between each child sequence and the parent sequence Lci(k)

- (7)

- Calculate the degree of correlation (γci) between each child sequence and the parent sequence

3. Results and Discussion

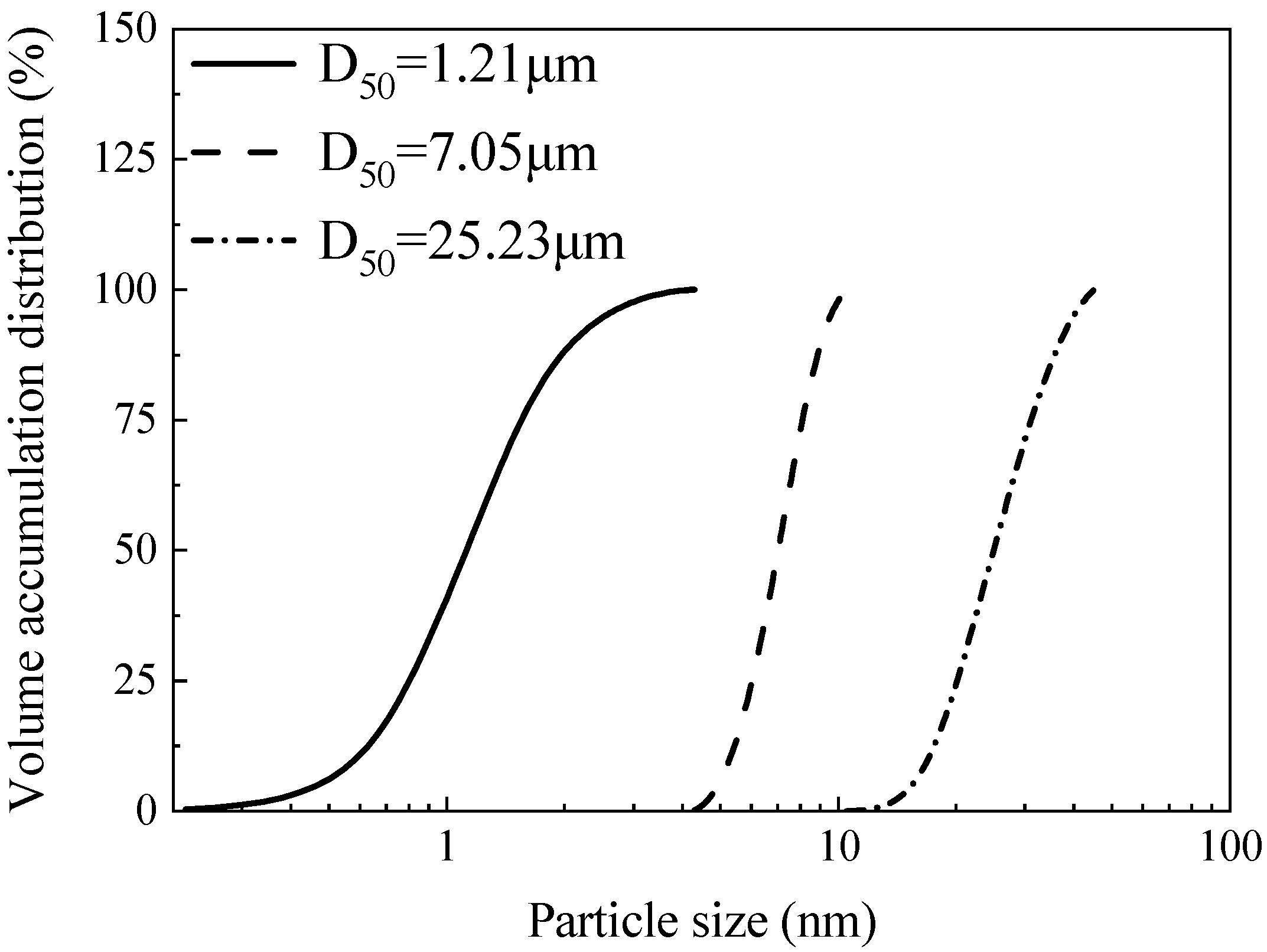

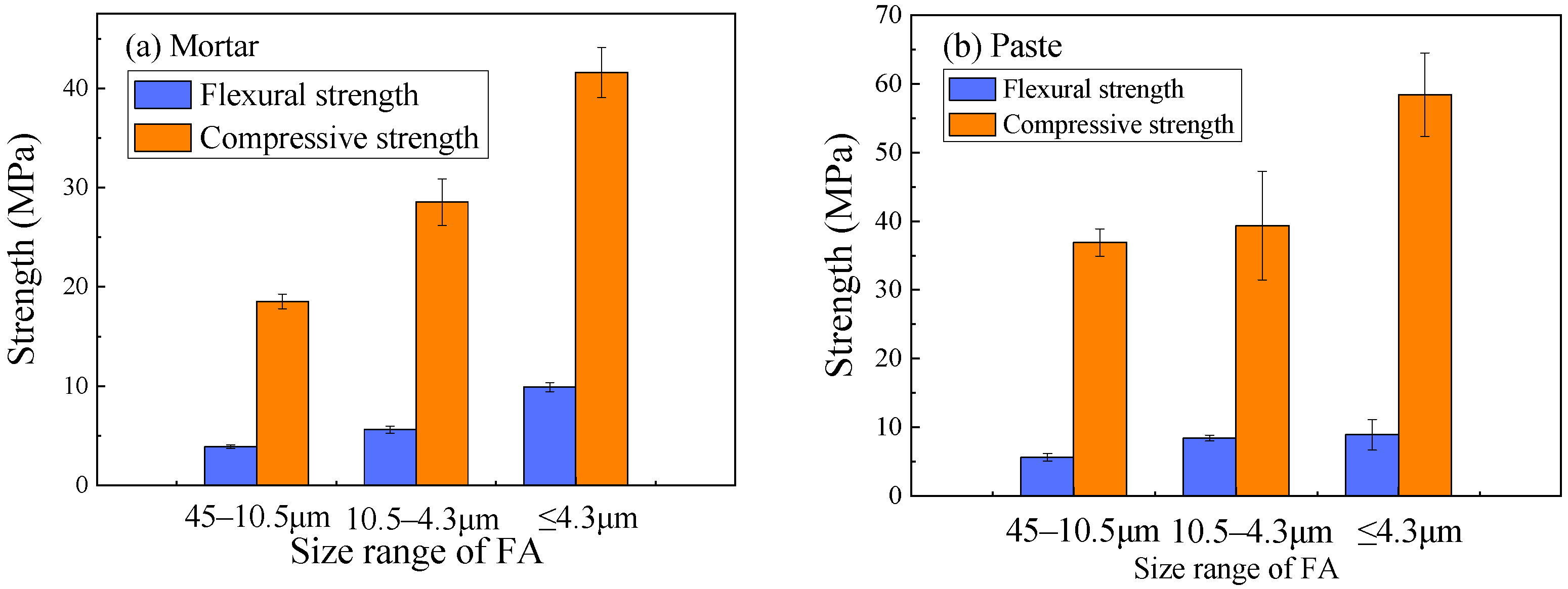

3.1. Effect of FA Particle Size on Mechanical Strength

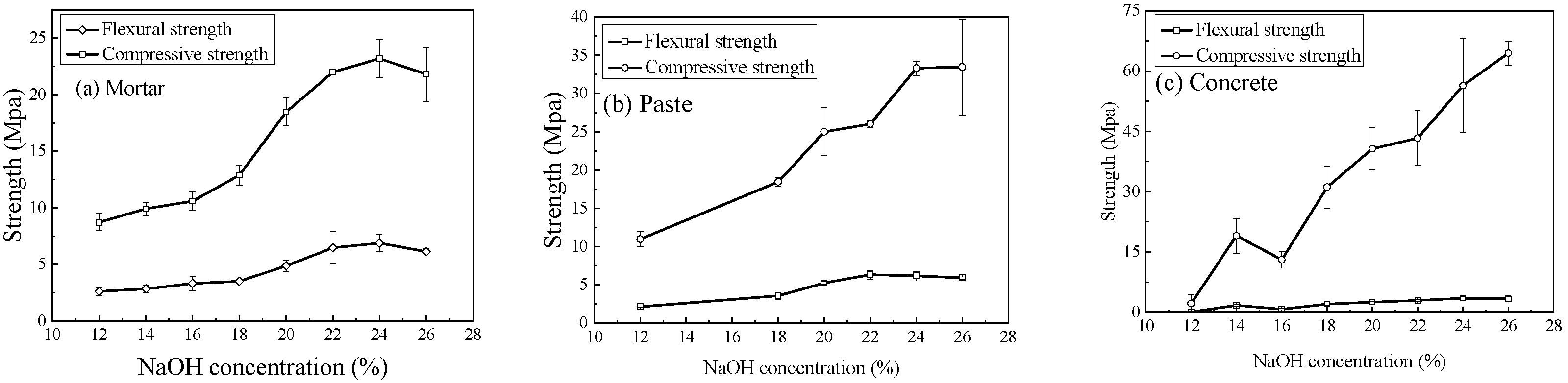

3.2. Effect of NaOH Concentration

3.3. Effect of Sodium Silicate Activator

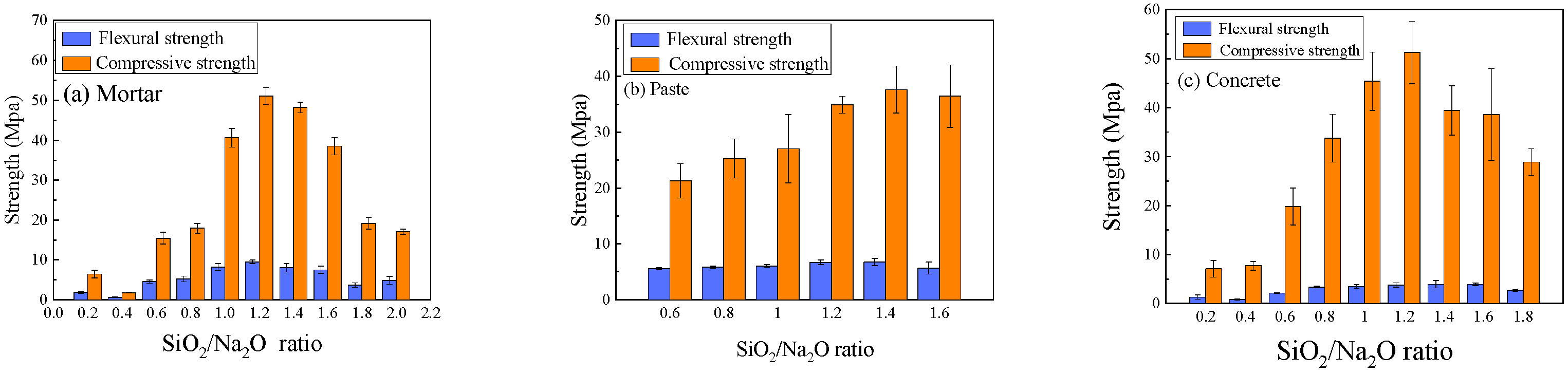

3.3.1. Effect of SiO2/Na2O Ratio

3.3.2. Effect of H2O/Na2O Ratio

3.4. Effect of Curing Conditions and Failure Modes

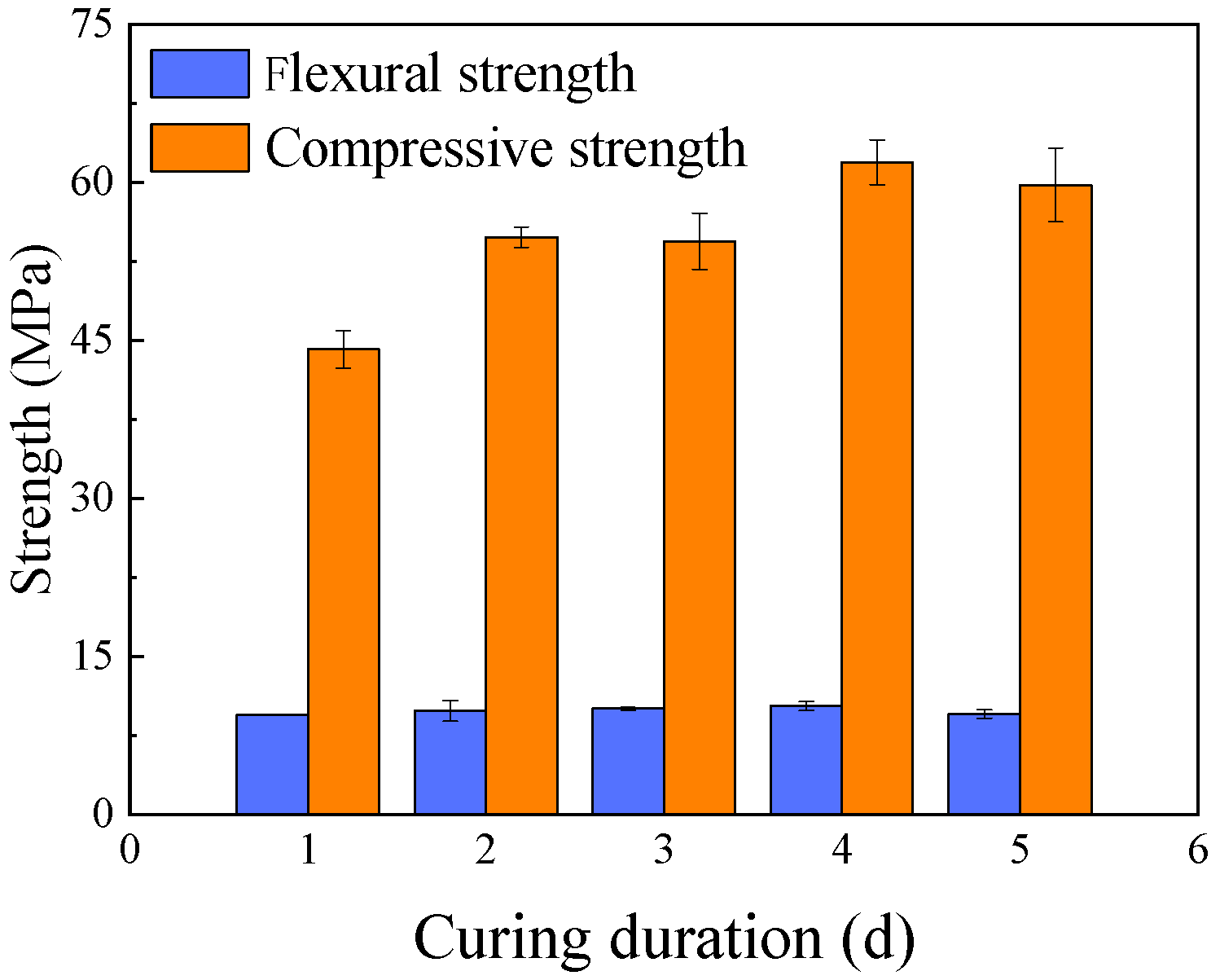

3.4.1. Effect of Curing Temperature and Duration

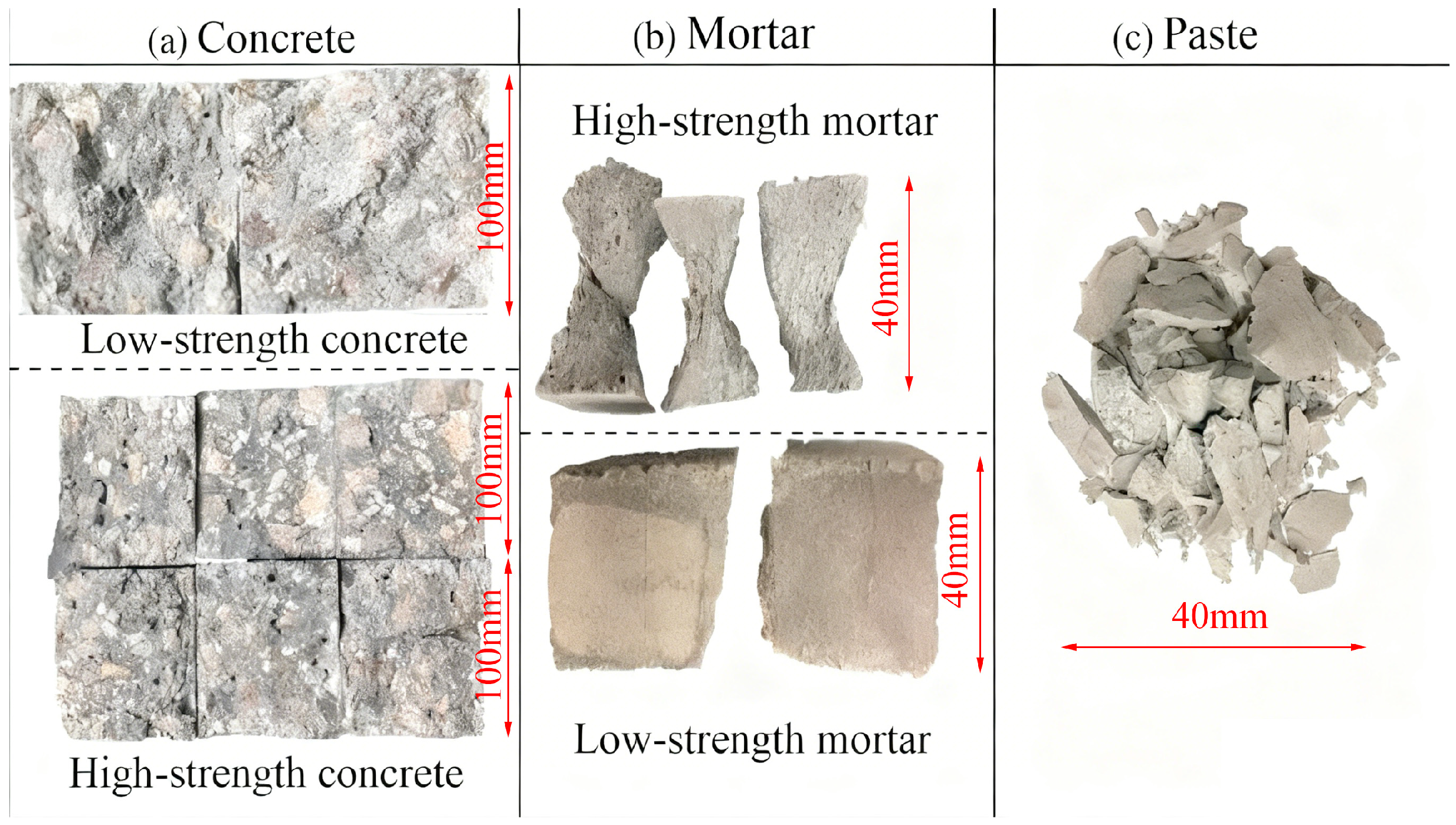

3.4.2. Failure Modes of Geopolymer Specimens

3.5. Effect of Mix Proportion Ratios

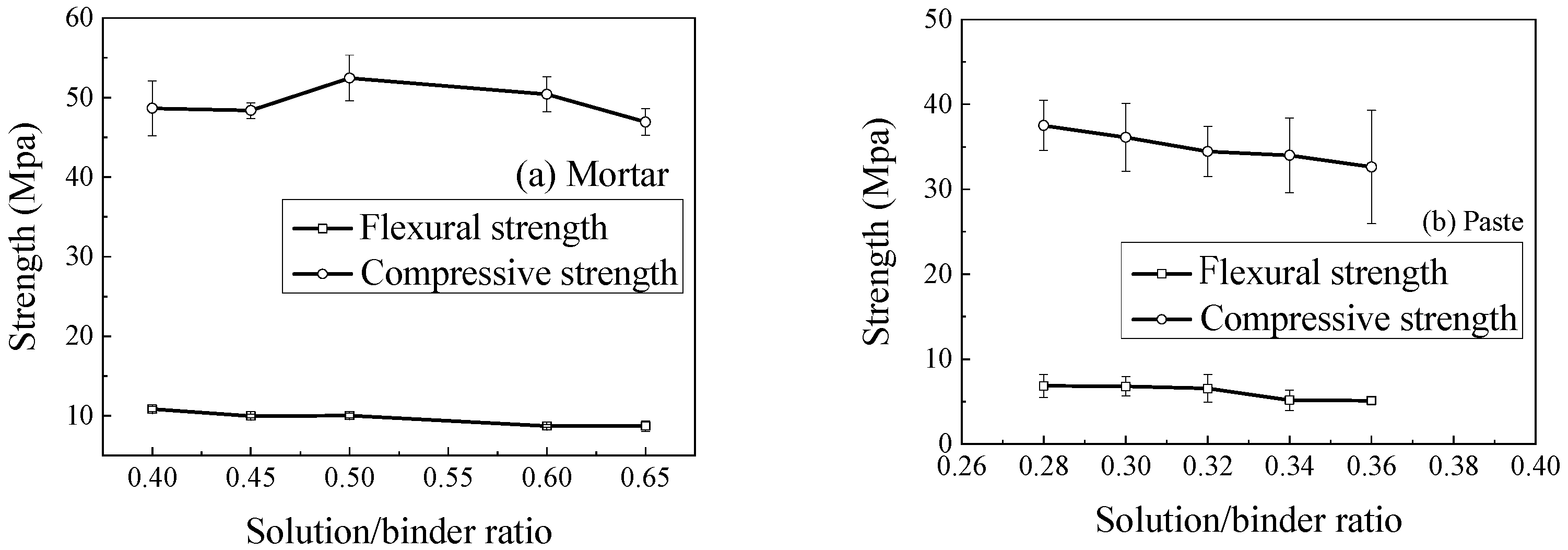

3.5.1. Effect of Solution/Binder Ratio

3.5.2. Effect of Binder/Sand Ratio

3.6. Grey Relational Analysis of Influencing Factors

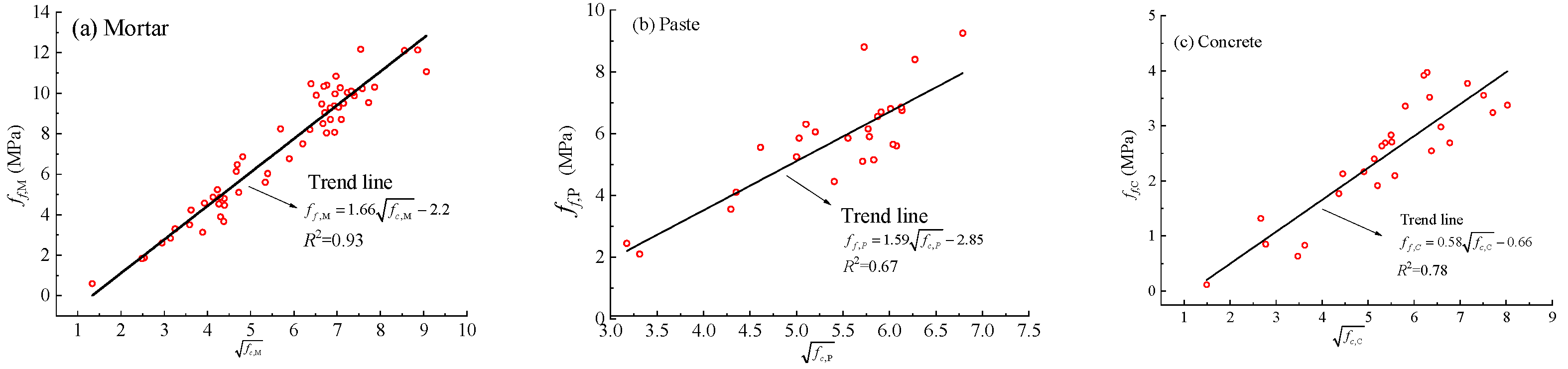

3.7. Correlation Between Compressive and Flexural Strength

3.8. Microstructural Analysis

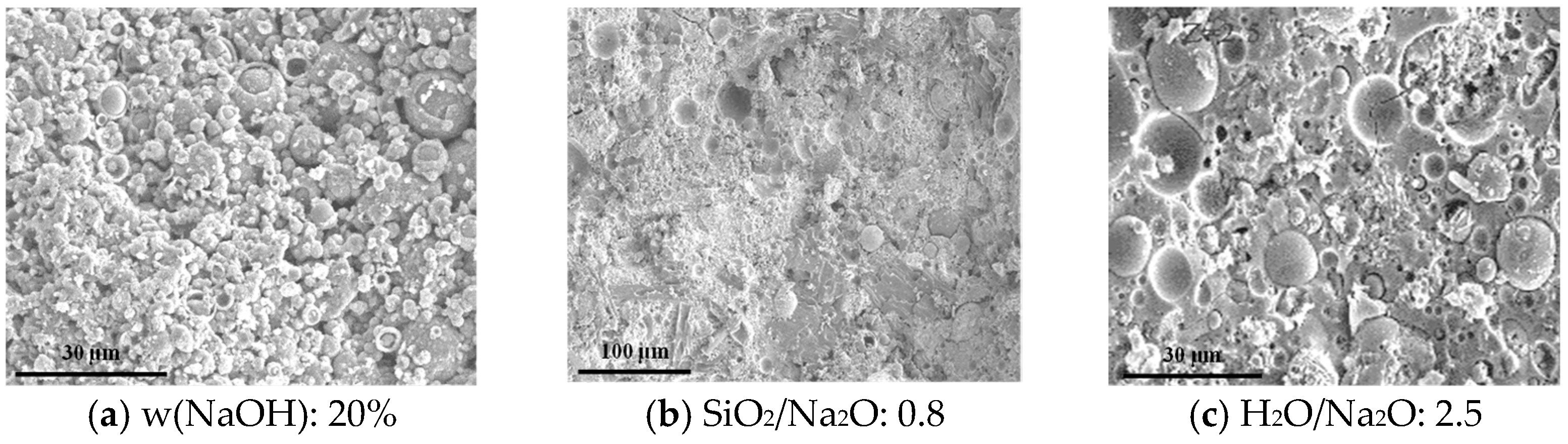

3.8.1. SEM Analysis

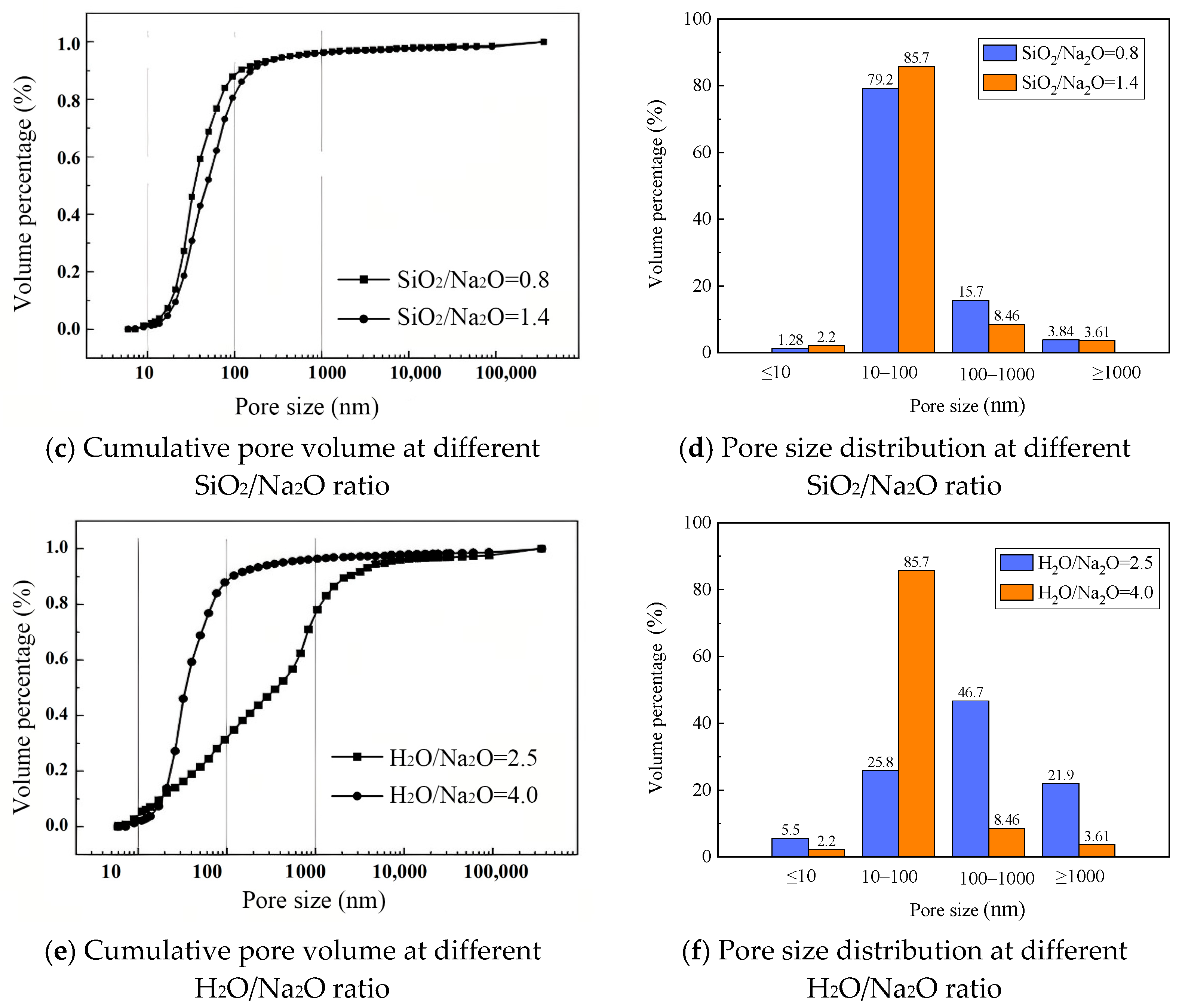

3.8.2. MIP Analysis

4. Predictive Models for Mechanical Strength

4.1. Multivariate Regression Model for Mortar Strength

4.2. Compressive Strength Prediction Model for Concrete Using Mortar Strength

4.2.1. Size Effect on Mortar Compressive Strength

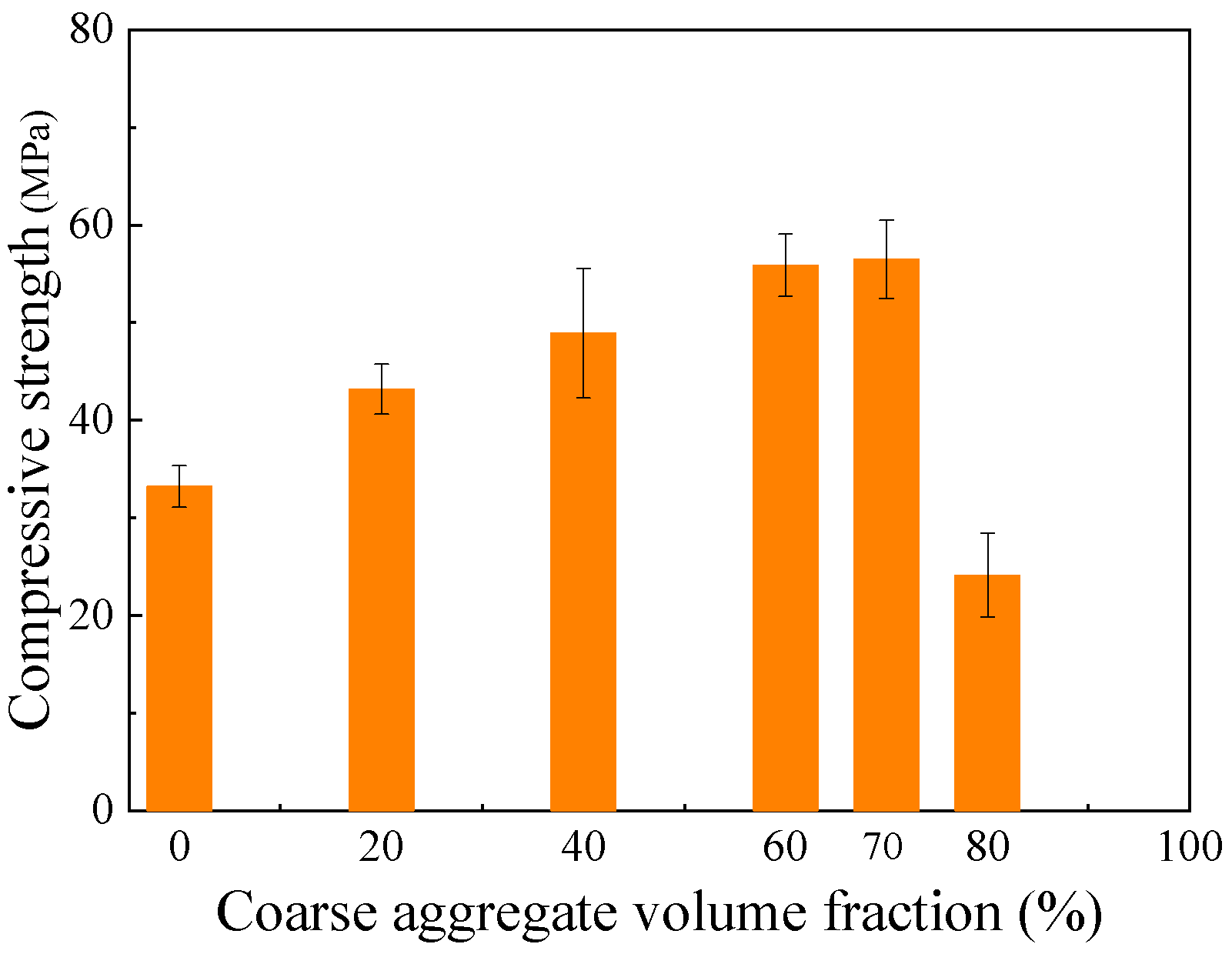

4.2.2. Effect of Coarse Aggregate Content

4.2.3. Final Predictive Model and Validation

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The chemical characteristics of the activator and the curing temperature are the primary factors controlling the mechanical performance of geopolymers. Both compressive and flexural (or splitting tensile) strengths initially increase and then decrease with rising NaOH concentration or sodium silicate modulus, with optimal ranges of 24~26% for NaOH concentration and 1.2~1.4 for the SiO2/Na2O ratio. Compressive and flexural strengths decrease almost linearly with increasing H2O/Na2O ratio, indicating that the lower limit of this ratio is dictated by workability requirements. Thermal curing accelerates strength development and temperatures of 70~80 °C markedly enhance reaction rates. Although prolonging heat curing can further increase geopolymer strength, the efficiency gain is limited; therefore, a curing duration within 24 h is recommended.

- (2)

- The mechanical strength of geopolymer mixtures is sensitive to mix proportions. For mortar, increasing the solution-to-binder ratio from 0.4 to 0.65 moderately reduces compressive strength and decreases flexural strength by 19.9%, indicating that the lowest ratio ensuring workability is preferable. An optimal binder-to-sand ratio also exists, as excessive binder can weaken tensile-related properties, while compressive strength remains relatively stable. For concrete, compressive strength increases with coarse aggregate content up to 60~70%, then declines. Careful selection of solution/binder, binder/sand, and aggregate ratios is therefore essential to optimize performance.

- (3)

- SEM and MIP analyses indicate that at 20% NaOH concentration, a SiO2/Na2O ratio of 0.8, and H2O/Na2O of 4.0, SEM images frequently show residual unreacted particles accompanied by increased microcracking and interparticle debonding. In contrast, at 30% NaOH, a SiO2/Na2O ratio of 1.2, and H2O/Na2O of 2.5, SEM reveals a progressive reduction in identifiable unreacted fly ash particles and the formation of a more homogeneous and dense gel matrix. MIP data further corroborate these observations: under the latter conditions, total porosity decreases and pore throats are refined, whereas the former conditions lead to increased meso- and macroporosity or reduced connectivity of the gel network. Overall, superior mechanical performance of geopolymer materials corresponds to higher gel content, fewer unreacted particles, and lower porosity.

- (4)

- Grey relational analysis ranks compressive strength influence as: curing temperature > silicate modulus > water content > liquid-to-solid ratio > binder-to-sand ratio > curing time > GGBFS content; flexural strength follows a similar trend. According to the regression analyses, all three material systems exhibited strong square-root-type correlations between compressive strength and flexural or splitting tensile strength. A generalized regression model was also developed to relate mortar strength to the compressive strength of geopolymer concrete, incorporating both size-effect and coarse-aggregate content corrections. The model further enables prediction of splitting tensile strength. At the current stage, partial validation indicates that the model can reliably capture the strength-variation trends of geopolymer concrete with respect to the SiO2/Na2O ratio, the H2O/Na2O ratio, and the binder-to-sand ratio.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| OPC | Ordinary Portland cement |

| FA | Fly ash |

| GGBFS | Ground granulated blast furnace slag |

| SiO2 | Silicon dioxide |

| Al2O3 | Aluminum oxide |

| NaOH | Sodium hydroxide |

| H2O | Water |

| Na2SiO3 | Sodium silicate solution |

| n | Molar ratio of silicon dioxide to sodium oxide |

| z | Molar ratio of water to sodium oxide |

| S | Mass ratio of activator solution to binder |

| C | Mass ratio of binder to sand |

| ω | Mass ratio of GGBFS to total binder |

| V | Volume fraction of coarse aggregate |

| T | Curing temperature |

| t | Curing duration |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| GRA | Grey relational analysis |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| D50 | Median particle sizes |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| MIP | Mercury intrusion porosimetry |

References

- Bărbulescu, A.; Hosen, K. Cement industry pollution and its impact on the environment and population health: A review. Toxics 2025, 13, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Abdalla, J.A.; Zhang, X. Eco-efficient high-strength engineered cementitious composites: Mechanical and self-healing behaviors influenced by fly ash content and particle size. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hawileh, R.A. Synergistic effect of waste steel slag powder and fly ash in sustainable high strength engineered cementitious composites: From microstructure to macro-performance. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Yang, F.; Weng, Y.; Qian, S. Sustainable high strength, high ductility engineered cementitious composites (ECC) with substitution of cement by rice husk ash. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Lu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Abdalla, J.A.; Hawileh, R.A. Incorporating nanomaterials into high strength ECC: Boosting self-healing and mechanical properties for marine infrastructure. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Abdalla, J.A.; Yu, J.; Chen, Y.; Hawileh, R.A.; Mahmoudi, F. Use of polypropylene fibers to mitigate spalling in high strength PE-ECC under elevated temperature. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Abdalla, J.A.; Hawileh, R.A. Incorporating expanded verminculites into high strength ECC: Improving its tensile properties and autogenous self-healing behavior. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 492, 142906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Lu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Abdalla, J.A.; Hawileh, R.A.; Zhang, X. Tailoring sustainable lightweight insulating ECC for structural use via incorporating recycled expanded polystyrene: Microstructural and mechanical properties. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 530, 146867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Qin, F.; Zhang, Z.; Di, J. Cyclic Behavior of GFRP-Reinforced ECC-Concrete Composite Bridge Columns: Experimental, Numerical, and Analytical Study. Compos. Part B Eng. 2026, 311, 113253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.; Nanda, B.; Patro, S.; Krishna, R. A comprehensive review on compressive strength and microstructure properties of GGBS-based geopolymer binder systems. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 417, 135242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Shi, B.; Dai, X.; Chen, C.; Lai, C. A State-of-the-Art Review on the Freeze–Thaw Resistance of Sustainable Geopolymer Gel Composites: Mechanisms, Determinants, and Models. Gels 2025, 11, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshani, F.; Kargari, A.; Norouzbeigi, R.; Mahmoodi, N.M. Role of fabrication parameters on microstructure and permeability of geopolymer microfilters. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 210, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, H.; Chen, J.; Dong, Z.; Li, L.-Y. Development of a ternary high-temperature resistant geopolymer and the deterioration mechanism of its concrete after heat exposure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genua, F.; Lancellotti, I.; Leonelli, C. Geopolymer-based stabilization of heavy metals, the role of chemical agents in encapsulation and adsorption. Polymers 2025, 17, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glukhovsky, V.D. Ancient, modern and future concretes. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Alkaline Cements and Concretes, Kiev, Ukraine, 11–14 October 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Davidovits, J.; Huaman, L.; Davidovits, R. Ancient organo-mineral geopolymer in South-American Monuments: Organic matter in andesite stone. SEM and petrographic evidence. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 7385–7399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, L.; Gan, Y.; Lv, L.; Dai, L.; Dai, W.; Lin, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z. Thermal impacts on eco-friendly ultra-lightweight high ductility geopolymer composites doped with low fiber volume. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 458, 139607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, J.A.; Thomas, B.S.; Hawileh, R.A.; Yang, J.; Jindal, B.B.; Ariyachandra, E. Influence of nano-TiO2, nano-Fe2O3, nanoclay and nano-CaCO3 on the properties of cement/geopolymer concrete. Clean. Mater. 2022, 4, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, J.A.; Hawileh, R.A.; Bahurudeen, A.; Jyothsna, G.; Sofi, A.; Shanmugam, V.; Thomas, B.S. A comprehensive review on the use of natural fibers in cement/geopolymer concrete: A step towards sustainability. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, M.S.; AnuPriya, A. Development and properties of low-calcium fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Int. J. Innov. Res. Adv. Eng. 2024, 11, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzali, S.A.E.; Shayanfar, M.A.; Ghanooni-Bagha, M.; Golafshani, E.; Ngo, T. The use of machine learning techniques to investigate the properties of metakaolin-based geopolymer concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 446, 141305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, F.S.; Fadel, O.; Selim, F.A.; Hassan, H.S. Examining the effect of hybrid activator on the strength and durability of slag-fine metakaolin based geopolymer cement. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 43, 101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, J.; Qin, F.; Sun, F. Thermal effect on mechanical properties of metakaolin-based engineered geopolymer composites (EGC). Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, R. Mechanical activation of fly ash: Effect on reaction, structure and properties of resulting geopolymer. Ceram. Int. 2011, 37, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi, L.N.; Deaver, E.E.; Ziehl, P. Effect of source and particle size distribution on the mechanical and microstructural properties of fly Ash-Based geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 167, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutsos, M.; Boyle, A.P.; Vinai, R.; Hadjierakleous, A.; Barnett, S.J. Factors influencing the compressive strength of fly ash based geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 110, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tome, S.; Nana, A.; Tchakouté, H.K.; Temuujin, J.; Rüscher, C.H. Mineralogical evolution of raw materials transformed to geopolymer materials: A review. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 35855–35868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; El-Korchi, T.; Zhang, G.; Liang, J.; Tao, M. Synthesis factors affecting mechanical properties, microstructure, and chemical composition of red mud–fly ash based geopolymers. Fuel 2014, 134, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somna, K.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Kajitvichyanukul, P.; Chindaprasirt, P. NaOH-activated ground fly ash geopolymer cured at ambient temperature. Fuel 2011, 90, 2118–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridtirud, C.; Chindaprasirt, P.; Pimraksa, K. Factors affecting the shrinkage of fly ash geopolymers. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2011, 18, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komljenović, M.; Baščarević, Z.; Bradić, V. Mechanical and microstructural properties of alkali-activated fly ash geopolymers. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 181, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.K.; Cao, Z.M.; Li, T.; Luo, X.P.; Yan, Q.; Chen, Q.; Huang, Z.J. Compressive strength and efflorescence extent of rare earth tailings-based geopolymer with different alkaline activators. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 35, 3819–3825. [Google Scholar]

- Görhan, G.; Kürklü, G. The influence of the NaOH solution on the properties of the fly ash-based geopolymer mortar cured at different temperatures. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 58, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmak, P.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Shen, S.L. Strength development in clay–fly ash geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 40, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Liu, R.; Qin, G.; Jiang, M.; Wu, Y.; Guo, Y. Study on high-ductility geopolymer concrete: The influence of oven heat curing conditions on mechanical properties and microstructural development. Materials 2024, 17, 4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayrak, B.; Akarsu, O.; Kılıç, M.; Alcan, H.G.; Çelebi, O.; Kaplan, G.; Aydın, A.C. Experimental study of bond behavior of geopolymer concrete under different curing conditions using a pull-out test. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 439, 137357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Majidi, M.H.; Lampropoulos, A.; Cundy, A.; Meikle, S. Development of geopolymer mortar under ambient temperature for in situ applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 120, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heah, C.Y.; Kamarudin, H.; Al Bakri, A.M.; Binhussain, M.; Luqman, M.; Nizar, I.K.; Ruzaidi, C.; Liew, Y. Effect of curing profile on kaolin-based geopolymers. Phys. Procedia 2011, 22, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovnaník, P. Effect of curing temperature on the development of hard structure of metakaolin-based geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1176–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencardino, F.; Mazzuca, P.; do Carmo, R.; Costa, H.; Curto, R. Cement-based mortars with waste paper sludge-derived cellulose fibers for building applications. Fibers 2024, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C618-23; Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ASTM C989/C989M-22a; Standard Specification for Slag Cement for Use in Concrete and Mortars. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- GB/T 17671-2021; Methods of Testing Cements—Determination of Strength (ISO Method). State Administration for Market Regulation and Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB/T 14685-2022; Pebbles and Crushed Stones for Construction. State Administration for Market Regulation and Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Mechanical Properties of Ordinary Concrete. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019.

| Sample | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | Na2O | K2O | SO3 | P2O5 | TiO2 | Others * | LOI ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fly ash, % | 59.87 | 24.66 | 4.14 | 3.84 | 1.23 | 0.45 | 0.18 | 0.71 | 0.30 | 1.27 | 0.15 | 3.20 |

| GGBFS, % | 33.20 | 15.00 | 0.81 | 35.07 | 6.34 | 0.39 | 0.61 | 2.43 | 0.00 | 2.34 | 1.51 | 2.30 |

| Geopolymer Materials | Solution/Binder Ratio | Binder/Sand Ratio | Sand Ratio | n | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paste | 0.4 | - | - | 1.0 | 4.0 |

| Mortar | 0.5 | 0.5 | - | 1.0 | 4.0 |

| Concrete | 0.5 | 0.6 | 33% | 1.0 | 4.0 |

| Single-Factor | Variable Range | Number of Specimens |

|---|---|---|

| FA fineness (μm) | 45–10.5, 10.5–4.3, ≤4.3 | 18 ** |

| NaOH concentration (%) | 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26 | 48 ** + 48 * |

| n | 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, 1.8, 2.0 | 60 ** + 60 * |

| z | 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0 | 30 ** + 24 * |

| T (°C) | 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90 | 18 ** |

| t (day) | 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0 | 15 ** |

| S | 0.4, 0.45, 0.5, 0.55, 0.6, 0.65 | 33 ** |

| C | 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8; (0.8, 1.0, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6) * | 15 ** + 30 * |

| ω (%) | 12.5, 20, 40, 60, 80 | 15 ** |

| D (mm) | 10, 40, 50, 70.7, 100 | 15 ** |

| V (%) | 0.0, 20, 40, 60, 70, 80 | 18 * |

| Parameter | n | z | T | t | s | c | ω |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compressive Strength | 0.8553 | 0.8531 | 0.8683 | 0.8044 | 0.8474 | 0.8447 | 0.8008 |

| Flexural Strength | 0.8862 | 0.8859 | 0.9040 | 0.8374 | 0.8816 | 0.8820 | 0.8278 |

| Variable | NaOH Concentration | SiO2/Na2O Ratio | H2O/Na2O Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20% | 30% | 0.8 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 4.0 | |

| Porosity | 21.4% | 19.7% | 21.0% | 19.8% | 14.4% | 19.8% |

| Average pore size | 96.4 nm | 153.8 nm | 112.2 nm | 42.5 nm | 60.3 nm | 32.6 nm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, S.; Abdalla, J.A.; Hawileh, R.A.; Liu, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Experimental Investigation on Factors Influencing the Early-Age Strength of Geopolymer Paste, Mortar, and Concrete. Materials 2025, 18, 5648. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245648

Yang S, Abdalla JA, Hawileh RA, Liu J, Yu Y, Zhang Z. Experimental Investigation on Factors Influencing the Early-Age Strength of Geopolymer Paste, Mortar, and Concrete. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5648. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245648

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Shiyu, Jamal A. Abdalla, Rami A. Hawileh, Jianhua Liu, Yaqin Yu, and Zhigang Zhang. 2025. "Experimental Investigation on Factors Influencing the Early-Age Strength of Geopolymer Paste, Mortar, and Concrete" Materials 18, no. 24: 5648. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245648

APA StyleYang, S., Abdalla, J. A., Hawileh, R. A., Liu, J., Yu, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2025). Experimental Investigation on Factors Influencing the Early-Age Strength of Geopolymer Paste, Mortar, and Concrete. Materials, 18(24), 5648. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245648