Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Performance of BiVO4 Photoanodes Through Few-Layer MoS2 Composite Formation for Efficient Water Oxidation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

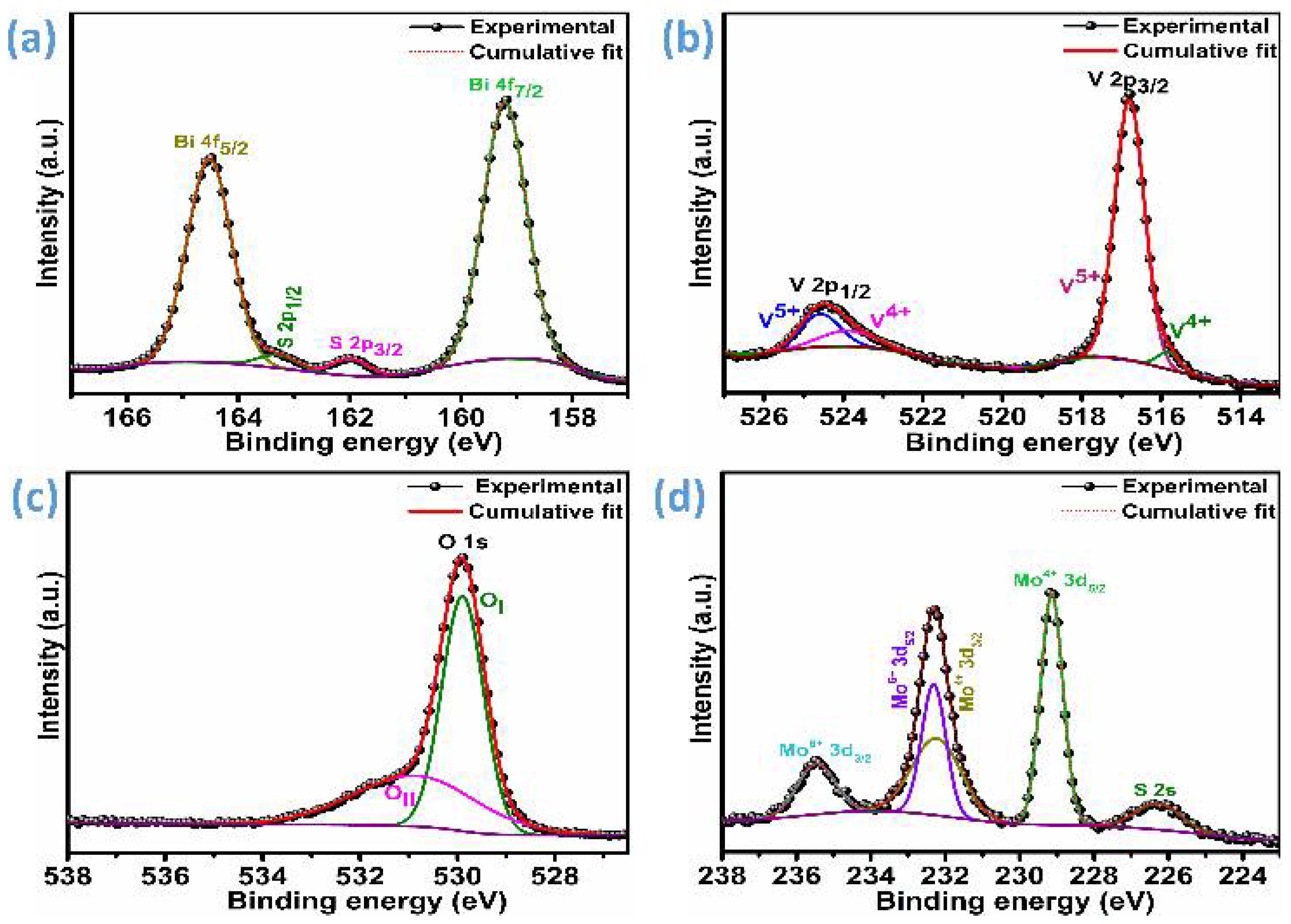

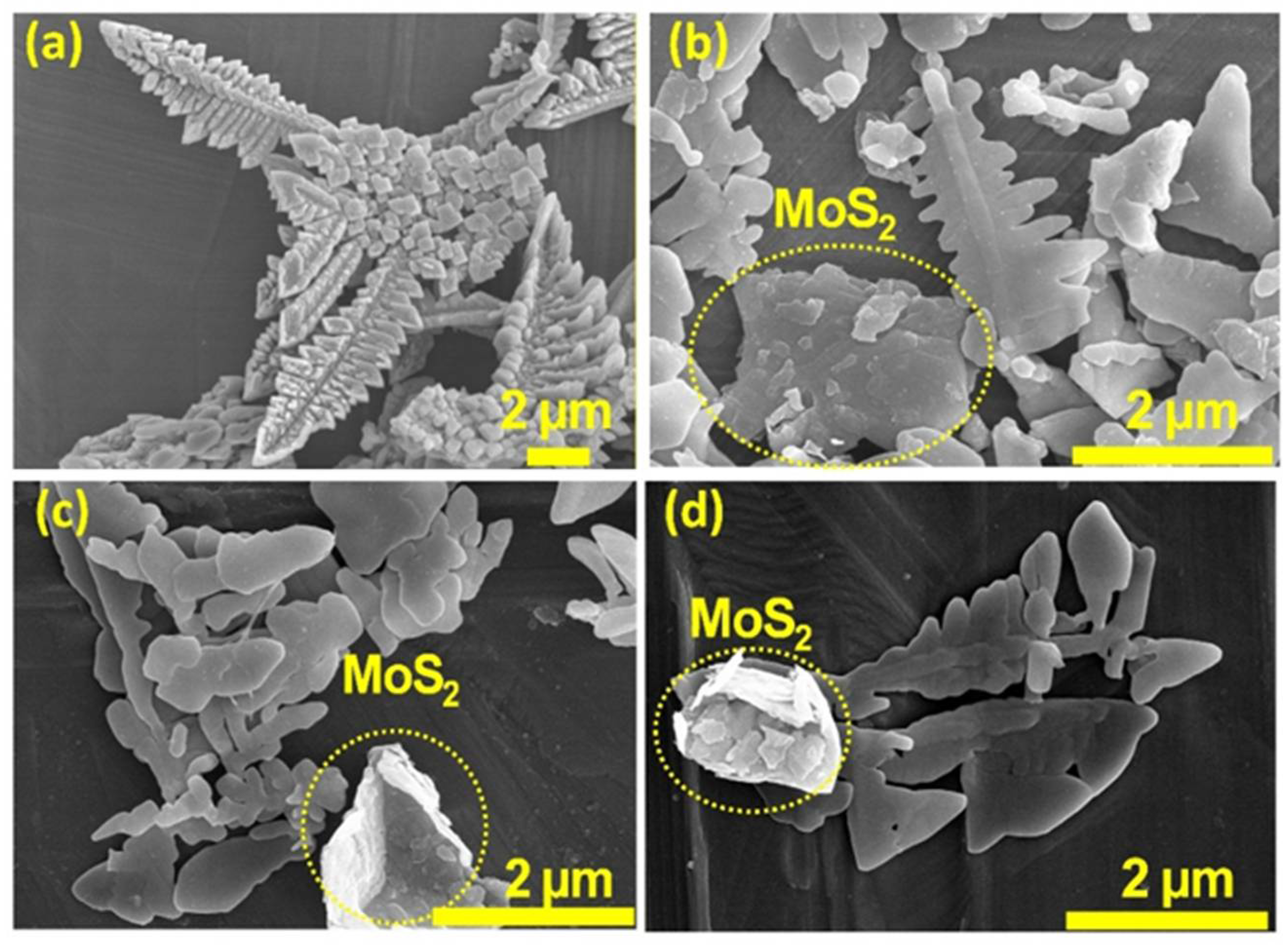

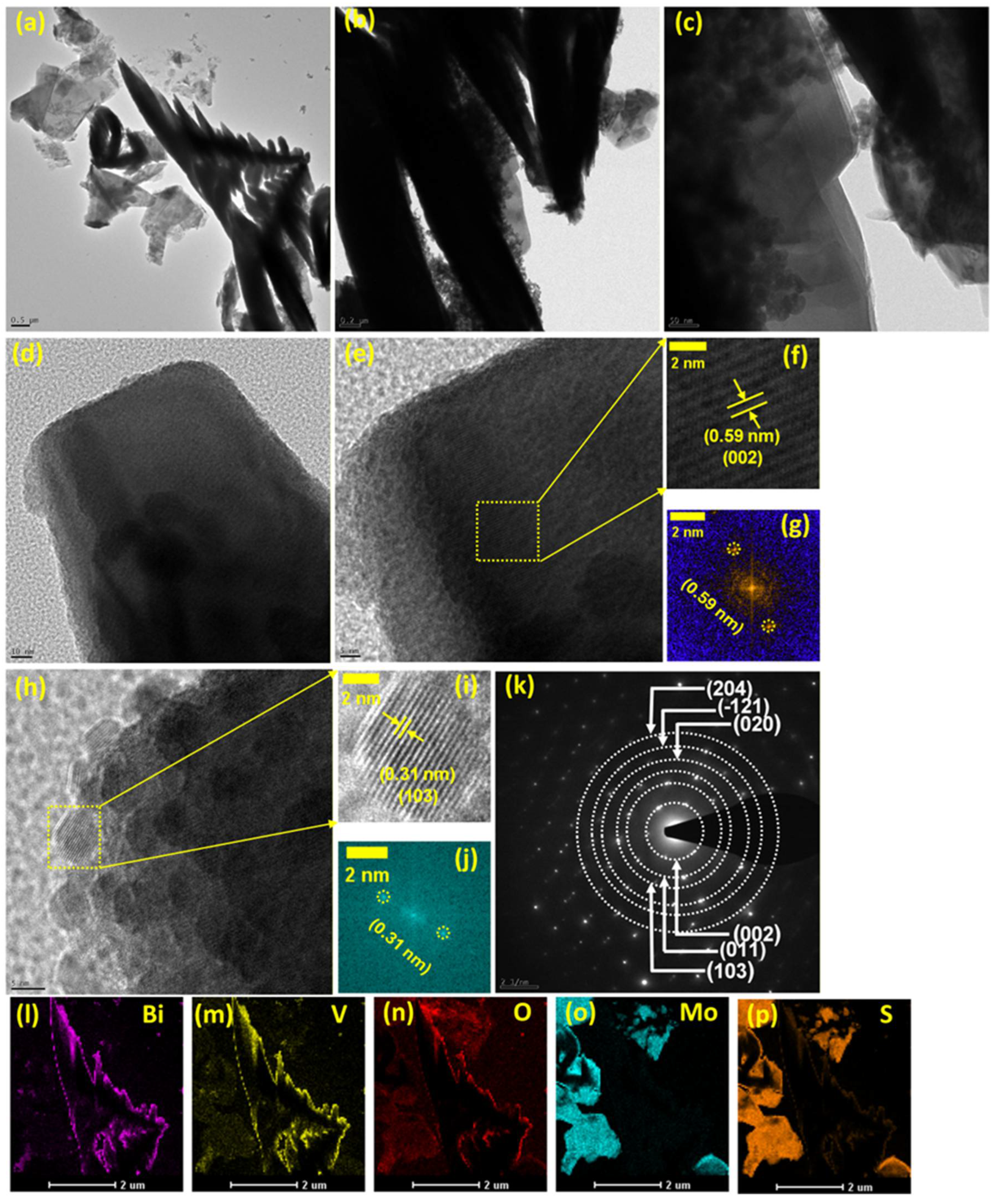

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chavan, G.T.; Dubal, D.P.; Cho, E.C.; Patil, D.R.; Gwag, J.S.; Mishra, R.K.; Mishra, Y.K.; An, J.; Yi, J. A Roadmap of Sustainable Hydrogen Production and Storage: Innovations and Challenges. Small 2025, 21, 2411444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.S.; Johar, M.A.; Hassan, M.A.; Patil, D.R.; Ryu, S.W. Anchoring MWCNTs to 3D Honeycomb ZnO/GaN Heterostructures to Enhancing Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation. Appl. Catal. B 2018, 237, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, G. Efficient Solar Energy Harvesting and Storage through a Robust Photocatalyst Driving Reversible Redox Reactions. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1802294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, Z.; Fang, D.; Low, J.; Yi, J. Covalent Bridges in Bi Loaded BiVO4 Enabling Rapid Charge Transfer for Efficient Photocatalytic Water Oxidation. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e00666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Domen, K. Particulate Photocatalysts for Light-Driven Water Splitting: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Design Strategies. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 919–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Fang, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Lin, W.; Wang, X. Remarkable Oxygen Evolution by Co-Doped ZnO Nanorods and Visible Light. Appl. Catal. B 2021, 296, 120369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Lindley, S.A.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.Z. Hematite Heterostructures for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting: Rational Materials Design and Charge Carrier Dynamics. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 2744–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninakanti, R.; Borah, R.; Craig, T.; Ciocarlan, R.G.; Cool, P.; Bals, S.; Verbruggen, S.W. Au@TiO2 Core-Shell Nanoparticles with Nanometer-Controlled Shell Thickness for Balancing Stability and Field Enhancement in Plasmon-Enhanced Photocatalysis. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 33430–33440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Da, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X.; Gong, X.; Zheng, G. WO3 Nanoflakes for Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Conversion. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 11770–11777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.W.; Cha, S.; Kwak, I.; Kwon, I.S.; Park, K.; Jung, C.S.; Cha, E.H.; Park, J. Surface-Modified Ta3N5 Nanocrystals with Boron for Enhanced Visible-Light-Driven Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 36715–36722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trześniewski, B.J.; Smith, W.A. Photocharged BiVO4 Photoanodes for Improved Solar Water Splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2016, 4, 2919–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xie, Z.; Li, W.; Aziz, H.S.; Abbas, M.; Zheng, Z.; Su, Z.; Fan, P.; Chen, S.; Liang, G. Charge Transport Enhancement in BiVO4 Photoanode for Efficient Solar Water Oxidation. Materials 2023, 16, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.S.; Mali, M.G.; Hassan, M.A.; Patil, D.R.; Kolekar, S.S.; Ryu, S.W. One-Pot in Situ Hydrothermal Growth of BiVO4/Ag/RGO Hybrid Architectures for Solar Water Splitting and Environmental Remediation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Liu, S.; Yao, L.; Li, X.; Deng, C.; Zhou, N.; Hu, K. BiVO4 Photoanode with Hole Transport Layer of Dual-Heterojunction for Efficient Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 540, 147280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Kang, H.J.; Magesh, G.; Kim, J.Y.; Jang, J.W.; Lee, J.S. Improved Photoelectrochemical Activity of CaFe2O4/BiVO4 Heterojunction Photoanode by Reduced Surface Recombination in Solar Water Oxidation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 17762–17769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh Thu, C.T.; Jo, H.J.; Koyyada, G.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, J.H. Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation Using TiO2-Co3O4 p–n Heterostructures Derived from in Situ-Loaded ZIF-67. Materials 2023, 16, 5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.B.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H.J.; Gao, L.J.; Li, L.; Cao, R.; Hao, Q.Y. Engineering Cu/NiCu LDH Heterostructure Nanosheet Arrays for Highly-Efficient Water Oxidation. Materials 2023, 16, 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Yang, S.; He, H.; Sun, C. Fabrication of a Novel P-n Heterojunction Photocatalyst n-BiVO4@p-MoS2 with Core-Shell Structure and Its Excellent Visible-Light Photocatalytic Reduction and Oxidation Activities. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 185, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Su, Y.; Ennaji, I.; Khojastehnezhad, A.; Siaj, M. Encapsulation of Few-Layered MoS2 on Electrochemical-Treated BiVO4 Nanoarray Photoanode: Simultaneously Improved Charge Separation and Hole Extraction towards Efficient Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yu, K.; Lei, X.; Guo, B.; Fu, H.; Zhu, Z. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Novel MoS2/BiVO4 Hetero-Nanoflowers with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity and a Mechanism Investigation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 22681–22689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Wu, D.; Xu, B.; Xu, H.; Cai, Z.; Peng, J.; Weng, J.; Xu, S.; Zhu, C.; Wang, F.; et al. Two-dimensional material-based saturable absorbers: Towards compact visible-wavelength all-fiber pulsed lasers. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mane, S.M.; Teli, A.M.; Tayade, N.T.; Pawar, K.J.; Kulkarni, S.B.; Choi, J.; Yoo, J.W.; Shin, J.C. Correlative structural refinement-magnetic tunability, and enhanced magnetostriction in low-temperature, microwave-annealed, Ni- substituted CoFe2O4 nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 895, 162627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, Z.; Tayebi, M.; Kolaei, M.; Tayyebi, A.; Ryu, H.; Jang, J.I.; Lee, B.K. Simultaneous Enhancement of Charge Separation and Hole Transportation in a W:α-Fe2O3/MoS2 Photoanode: A Collaborative Approach of MoS2 as a Heterojunction and W as a Metal Dopant. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 39215–39229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, T.; Dong, W. In Situ Photoelectrochemical Activation of Sulfite by MoS2 Photoanode for Enhanced Removal of Ammonium Nitrogen from Wastewater. Appl. Catal. B 2019, 244, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, X.; Yan, H.; Wu, G.; Ma, G.; Wen, F.; Wang, L.; Li, C. Enhancement of Photocatalytic H2 Evolution on CdS by Loading MoS2 as Cocatalyst under Visible Light Irradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 7176–7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdavi, M.; Kimiagar, S.; Abrinaei, F. Preparation of Few-Layered Wide Bandgap MoS2 with Nanometer Lateral Dimensions by Applying Laser Irradiation. Crystals 2020, 10, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alebachew, N.; Ananda Murthy, H.C.; Gonfa, B.A.; Eschwege, K.G.; Langner, E.H.G.; Coetsee, E.; Demissie, T.B. Nanocomposites with ZrO2@S-Doped g-C3N4 as an Enhanced Binder-Free Sensor: Synthesis and Characterization. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 13775–13790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, A.F.; Hernández-Barreto, D.F.; Bernal, V.; Giraldo, L.; Moreno-Piraján, J.C.; Silva, E.A.; Alves, M.C.M.; Morais, J.; Hernandez, Y.; Cortés, M.T.; et al. Sulfur-Doped g-C3N4 Heterojunctions for Efficient Visible Light Degradation of Methylene Blue. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 47821–47834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.B.; Shafiq, F.; Sagir, M.; Tahir, M.S. Construction of visible-light-driven ternary ZnO-MoS2-BiVO4 composites for enhanced photocatalytic activity. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 11, 241–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.J.; Tu, J.R.; Ye, Z.J.; Chen, D.Q.; Hu, B.; Huang, Y.W.; Chen, T.T.; Cao, D.P.; Yu, Z.T.; Zou, Z.G. MoS2-graphene/ZnIn2S4 hierarchical microarchitectures with anelectron transport bridge between light-harvesting semiconductorand cocatalyst: A highly efficient photocatalyst for solar hydrogen generation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 188, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govinda Raj, M.; Vijaykumar, E.; Preetha, R.; Narendran, M.G.; Neppolian, B.; Bosco, A.J. Implanting TiO2@MoS2/BiVO4 nanocomposites via sonochemically assisted photoinduced charge carriers promotes highly efficient photocatalytic removal of tetracycline. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 929, 167252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Long, X.; Wei, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, T.; Li, F.; Hu, Y.; Ma, J.; Jin, J. Facile Growth of AgVO3 Nanoparticles on Mo-Doped BiVO4 Film for Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 378, 122193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; He, G.S.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Li, J. Engineering Heteropolyblue Hole Transfer Layer for Efficient Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting of BiVO4 Photoanodes. Appl. Catal. B 2024, 349, 123895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, G.; Wang, J.; Li, A.; Corvini, P.F.X. Engineering Efficient Hole Transport Layer Ferrihydrite-MXene on BiVO4 Photoanodes for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting: Work Function and Conductivity Regulated. Appl. Catal. B 2022, 315, 121606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Xue, K.; Luo, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Y. Phase Engineering of 1 T-MoS2 on BiVO4 Photoanode with p–n Junctions: Establishing High Speed Charges Transport Channels for Efficient Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 144965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, H.; Du, L.; Tian, G. Efficient Separation of Photogenerated Charges in Sandwiched Bi2S3−BiOCl Nanoarrays/BiVO4 Nanosheets Composites for Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 3223–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, G.; Tang, L.; Xu, Y.; Ma, C.; Chen, Z.; Han, S.; Yan, M.; Lu, Z. Construction of a Direct Z-Type Heterojunction Relying on Mos2 Electronic Transfer Platform Towards Enhanced Photodegradation Activity of Tetracycline. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Jung, D.; Park, C.Y.; Kang, D.J. Synthesis of Single-Crystalline Sodium Vanadate Nanowires Based on Chemical Solution Deposition Method. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2015, 165, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.T.; Ma, C.H.; Luong, T.T.; Wei, L.L.; Yen, T.C.; Hsu, W.T.; Chang, W.H.; Chu, Y.C.; Tu, Y.Y.; Pande, K.P.; et al. Layered MoS2 grown on c-sapphire by pulsed laser deposition. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 2015, 9, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Dela Pena, T.A.; Seo, S.; Choi, H.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Woo, J.; Choi, C.H.; Lee, S. Co-Catalytic Effects of Bi-Based Metal–Organic Framework on BiVO4 Photoanodes for Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 563, 150357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yu, S.; Dai, Y.; Huang, X.; Chou, L.; Lu, G.; Dong, G.; Bi, Y. Nitrogen-Incorporation Activates NiFeOx Catalysts for Efficiently Boosting Oxygen Evolution Activity and Stability of BiVO4 Photoanodes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liang, X.; Wang, P.; Huang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, X.; Zhang, X. Fabrication of Large Size Nanoporous BiVO4 Photoanode by a Printing-Like Method for Efficient Solar Water Splitting Application. Catal. Today 2020, 340, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Patil, S.S.; Lee, K. Nanospace-Confined Worm-Like BiVO4 in TiO2 Space Nanotubes (SPNTs) for Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Production. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 432, 141213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, M.; Dey, S.; Rao, C.N.R. Photoelectrochemical Oxygen Evolution Reaction Activity of Amorphous Co–La Double Hydroxide–BiVO4 Fabricated by Pulse Plating Electrodeposition. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 1062–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Hisatomi, T.; Kuang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, M.; Iwase, A.; Jia, Q.; Nishiyama, H.; Minegishi, T.; Nakabayashi, M.; et al. Surface Modification of CoOx-Loaded BiVO4 Photoanodes with Ultrathin p-Type NiO Layers for Improved Solar Water Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5053–5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Yoo, J.E.; Lee, K. Enhanced photoelectrochemical hydrogen production via linked BiVO4 nanoparticles on anodic WO3 nanocoral structures. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2024, 8, 1448–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.W.; Siao, Y.S.; Lai, Y.H.; Hsieh, P.Y.; Tsao, C.W.; Lu, Y.J.; Chen, Y.C.; Hsu, Y.J.; Chu, Y.C. Flexible BiVO4/WO3/ITO/Muscovite Heterostructure for Visible-Light Photoelectrochemical Photoelectrode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 21186–21193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, A.; Bian, W.; Corvini, P.F.-X. Au@CoS-BiVO4 {010} Constructed for Visible-Light-Assisted Peroxymonosulfate Activation. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patil, D.R.; Patil, S.S.; Mishra, R.K.; Mane, S.M.; Ryu, S.Y. Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Performance of BiVO4 Photoanodes Through Few-Layer MoS2 Composite Formation for Efficient Water Oxidation. Materials 2025, 18, 5639. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245639

Patil DR, Patil SS, Mishra RK, Mane SM, Ryu SY. Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Performance of BiVO4 Photoanodes Through Few-Layer MoS2 Composite Formation for Efficient Water Oxidation. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5639. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245639

Chicago/Turabian StylePatil, Deepak Rajaram, Santosh S. Patil, Rajneesh Kumar Mishra, Sagar M. Mane, and Seung Yoon Ryu. 2025. "Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Performance of BiVO4 Photoanodes Through Few-Layer MoS2 Composite Formation for Efficient Water Oxidation" Materials 18, no. 24: 5639. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245639

APA StylePatil, D. R., Patil, S. S., Mishra, R. K., Mane, S. M., & Ryu, S. Y. (2025). Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Performance of BiVO4 Photoanodes Through Few-Layer MoS2 Composite Formation for Efficient Water Oxidation. Materials, 18(24), 5639. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245639