Properties of n-Octadecane PCM Composite with Recycled Aluminum as a Thermal Enhancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

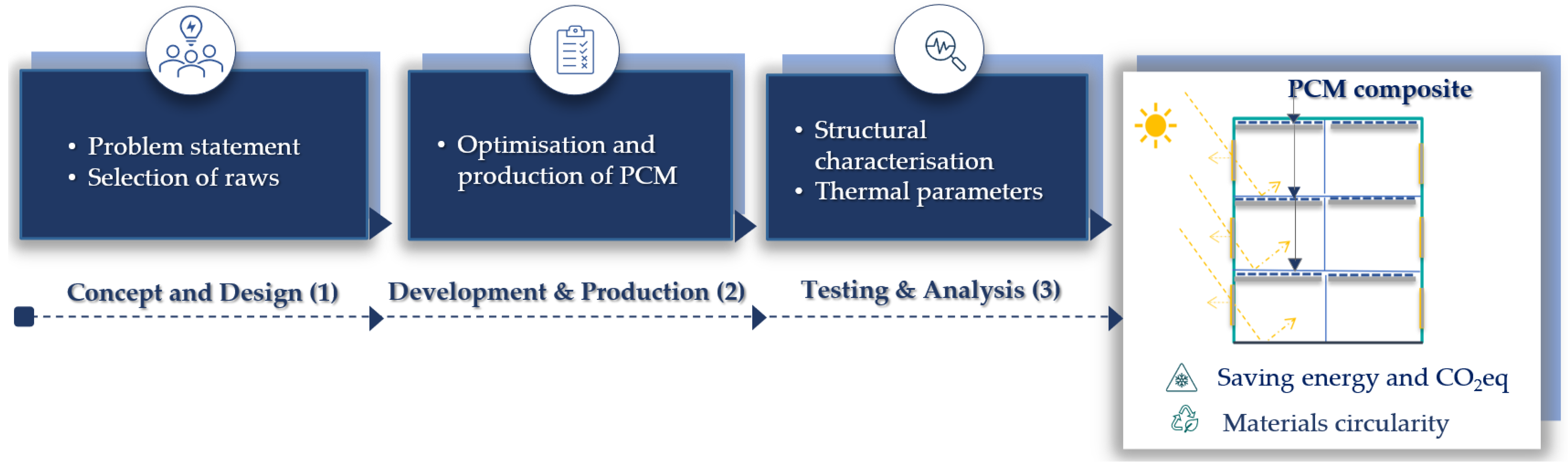

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Preparation of PCM Composites

2.3. Experimental Study and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermal Characterization of the PCM Composite

3.1.1. Non-Isothermal DTA Analysis

3.1.2. Isothermal Melting Analysis

3.1.3. Thermophysical Parameters

- -

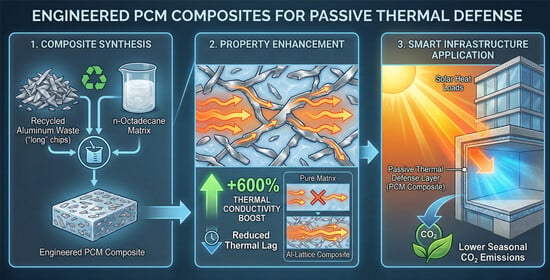

- Cost efficiency: The material cost is exceptionally low, maximizing the cost/benefit ratio for thermal enhancement.

- -

- Superior thermal enhancement: Due to the metallic nature and high intrinsic thermal conductivity of aluminum, it provides a much higher absolute conductivity increase compared to most oxide or ceramic fillers SiO2.

- -

- Environmental sustainability: Recycling aluminum supports the circular economy model by reusing waste material, with almost no supplementary energy input.

3.2. Mass of Composite Required for Passive Cooling

4. Conclusions

- -

- Recycled aluminum was selected for composite production. This was considered a simple and environmentally friendly way to increase the materials’ circularity, as well as to improve the thermal parameters of the composites. Al chips were used in two different percentages and lengths to exploit the maximum of their potential. The results show an increase of thermal conductivity from 0.22 W/m·K (n-octadecane) to 1.54 W/m·K, by approximately 600%, in the case of n-octadecane-Al-long. This was more effective than n-octadecane-Al-short, since its length permits fewer contact points for heat transfer.

- -

- Looking at the DTA curves, it was observed that the melting peak temperature (Tp) shifted to lower temperatures as the aluminum content increased.

- -

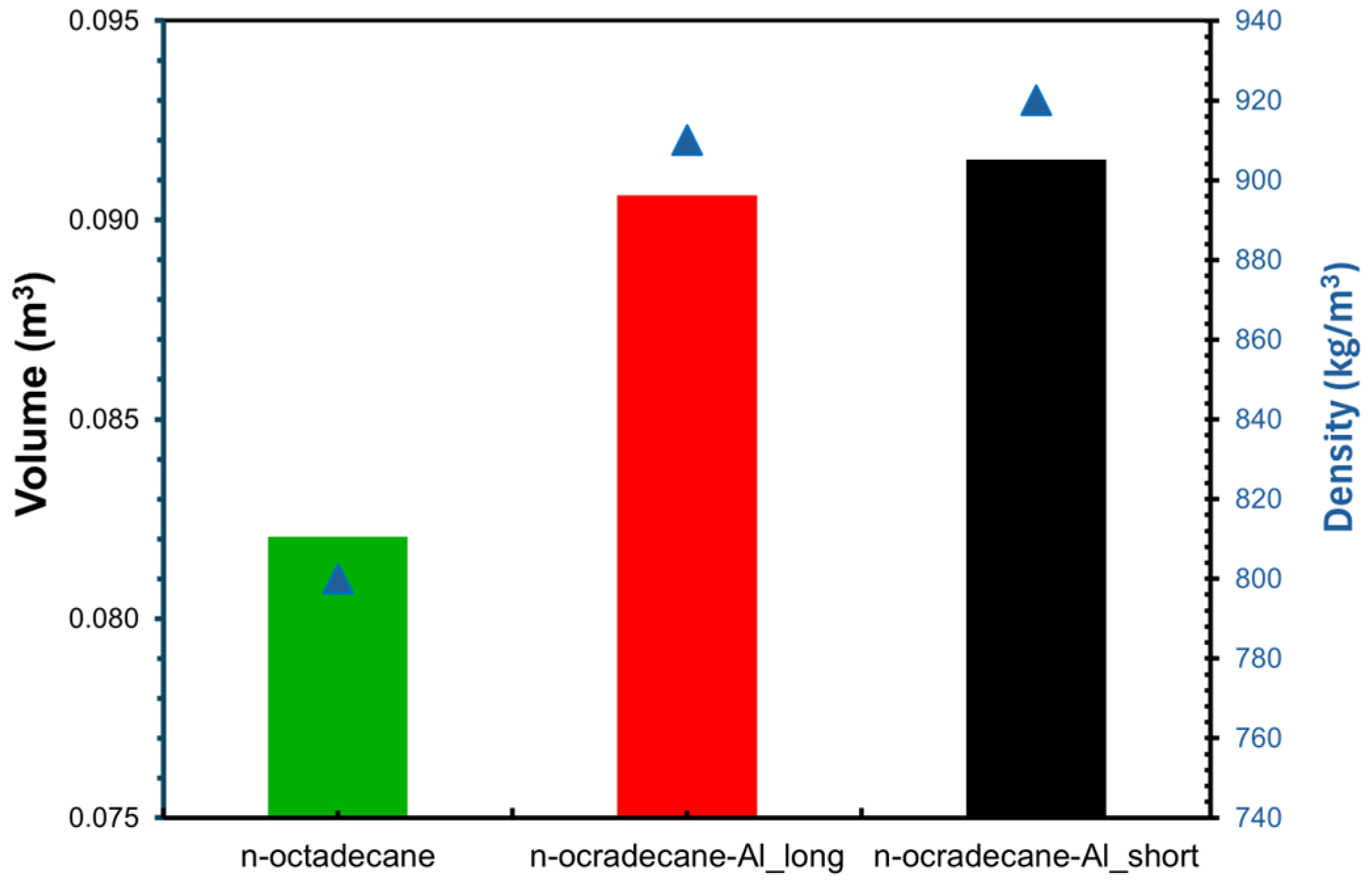

- The volume of PCM composites varied from 0.083 m3 for n-octadecane and 0.092 for n-octadecane-Al-short, which represents an increase of about 11%, which is required to absorb solar heat gains by the optimized PCM composite.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deroubaix, A.; Labuhn, I.; Camredon, M.; Gaubert, B.; Monerie, P.M.; Popp, M.; Ramarohetra, J.; Ruprich-Robert, Y.; Silvers, L.G.; Siour, G. Large uncertainties in trends of energy demand for heating and cooling under climate change. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Xin, Y.; He, T.; Zhao, G. A review of studies involving the effects of climate change on the energy consumption for building heating and cooling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Saeed, T. Space cooling achievement by using lower electricity in hot months through introducing PCM-enhanced buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 53, 104506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, K.; Medina, M.A. A parametric study on the thermal response of a building wall with a phase change material (PCM) layer for passive space cooling. J. Energy Storage 2022, 47, 103548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Absi, Z.A.; Asif, M.; Hafizal, M.I.M. Optimization study for PCM application in residential buildings under desert climatic conditions. J. Energy Storage 2024, 104, 114399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzabad, M.R.; Pourfayaz, F. The impact of using PCM layers in simultaneously the external and internal walls of building on energy annual consumption. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 24, 100689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.X.; Chen, X.N.; Xu, B.; Pei, G.; Jiao, D.S. Experimental analysis of building envelope integrating phase change material and cool paint under a real environment in autumn. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 461, 142674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, H. Review of Classification of PCMs, with a Focus on the Search for New, Suitable PCM Candidates. Energies 2024, 17, 4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abass, P.J.; Muthulingam, S. Comprehensive assessment of PCM integrated roof for passive building design: A study in energo-economics. Energy Build. 2024, 317, 114387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Torres, J.F.; Wang, X. PCM-based ceiling panels for passive cooling in buildings: A CFD modelling. Energy Build. 2023, 285, 112898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zhang, X.; Ji, J. Hygroscopic phase change composite material A review. J. Energy Storage 2021, 36, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jebaei, H.; Aryal, A.; Jeon, I.K.; Azzam, A.; Kim, Y.R.; Baltazar, J.C. Evaluating the potential of optimized PCM-wallboards for reducing energy consumption and CO2 emission in buildings. Energy Build. 2024, 315, 114320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, P.K.S.; Gupta, N.K.; Yadav, D.; Shukla, S.K.; Kaul, S. Thermal performance of the building envelope integrated with phase change material for thermal energy storage: An updated review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 79, 103690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbasi, R.; Hassani, P. Buildings with less HVAC power demand by incorporating PCM into envelopes taking into account ASHRAE climate classification. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 51, 104303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshuraiaan, B. Efficient utilization of PCM in building envelope in a hot environment condition. Int. J. Thermofluids 2022, 16, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizovtsev, M.I.; Sterlyagov, A.N. Effect of phase change material (PCM) on thermal inertia of walls in lightweight buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 82, 107912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.L.; Walvekar, R.; Wong, W.P.; Sharma, R.K.; Dharaskar, S.; Khalid, M. Advances in phase change materials, heat transfer enhancement techniques, and their applications in thermal energy storage: A comprehensive review. J. Energy Storage 2024, 87, 111329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atinafu, D.G.; Choi, J.Y.; Yun, B.Y.; Nam, J.; Kim, H.B.; Kim, S. Energy storage and key derives of octadecane thermal stability during phase change assembly with animal manure-derived biochar. Environ. Res. 2024, 240, 117405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Jia, Y.; Alva, G.; Fang, G. Review on thermal conductivity enhancement, thermal properties and applications of phase change materials in thermal energy storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2730–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalmaier, G.; Cobîrzan, N.; Sechel, N.A.; Vida-Simiti, I. Paraffin Graphite Composite Spheres for Thermal Energy Management. Materials 2025, 18, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G.T.; Hwang, H.S.; Lee, J.; Cha, D.A.; Park, I. n-Octadecane/fumed silica phase change composite as building envelope for high energy efficiency. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, R.; Wang, G.; Yu, W.; Su, H.; Su, L. Study on the preparation and properties of TiO2@ n-octadecane phase change microcapsules for regulating building temperature. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 249, 123429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhang, H.; Fang, G. Review on thermal conductivity improvement of phase change materials with enhanced additives for thermal energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Ma, C.; Wang, W. Study on the effect of different additives on improving the thermal conductivity of organic PCM. Phase Transit. 2022, 95, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choure, B.K.; Alam, T.; Kumar, R. A review on heat transfer enhancement techniques for PCM based thermal energy storage system. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Biswas, N.; Datta, A.; Manna, N.K.; Mandal, D.K.; Biswas, S. A comprehensive review on enhanced phase change materials (PCMs) for high-performance thermal energy storage: Progress, challenges, and future perspectives. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 50, 8933–8976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, K.; Lu, L.; Zhao, L.; Wang, G. Towards passive building thermal regulation: A state-of-the-art review on recent progress of PCM-integrated building envelopes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.H.; Ali, A.A.U.; Mezan, S.O. Synthesis and Characterization of Silica Nanoparticle (Sio2 Nps) Via Chemical Process. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 25, 6211–6218. [Google Scholar]

- Saikam, L.; Arthi, P.; Senthil, B.; Shanmugam, M. A review on exfoliated graphite: Synthesis and applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 152, 110685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, P.; Nagarajan, R.D.; Shetty, B.H.; Govindasamy, M.; Sundramoorthy, A.K. Recent trends in the applications of thermally expanded graphite for energy storage and sensors–a review. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 6294–6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69. Available online: https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C593453&Units=SI&Mask=FFF (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Information on Aluminium 6060. Available online: https://www.thyssenkrupp-materials.co.uk/aluminium-6060.html (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Aluminium Alloy-Commercial Alloy-6060-T5 Extrusions. Available online: https://www.aalco.co.uk/datasheets/Aluminium-Alloy-6060-T5--Extrusions_144.ashx (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- I5-2022; Normativ Pentru Proiectarea, Executarea Și Exploatarea Instalațiilor De Ventilare Și Climatizare., M.Of. Nr.3. 108 si 108 bis/8 Februarie 2023 (Norm for the Design, Execution and Operation of Ventilation and Air Conditioning Systems). Guvernul Romaniei: București, România, 2011. (In Romanian)

- C107/7-02; Normativ Pentru Proiectarea La Stabilitatea Termica A Elementelor De Inchidere Ale Cladirilor, published in B.C. nr. 8/2003 (Norm for the Design of Thermal Stability of Building Enclosing Elements). Available online: https://www.mdlpa.ro/userfiles/reglementari/Domeniul_IX/09_13_C_107_7_2002.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025). (In Romanian)

- Kissinger, H.E. Reaction Kinetics in Differential Thermal Analysis. Anal. Chem. 1957, 29, 1702–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, J.; He, M.; Song, S. Effects of Dopamine-Modified and Organic Intercalation on the Thermophysical Properties of Octadecane/Expanded Vermiculite Composite Phase Change Materials. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 13538–13545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalmaier, G.; Cobîrzan, N.; Fechete-Tutunaru, L.V.; Balan, M.C. Recycled Aluminum Paraffin Composite for Passive Cooling Application in Buildings. Materials 2025, 18, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.S.; Joshi, D.P. Effect of identical supporting matrix on thermal performance and shape stability of octadecane and paraffin wax phase change material. J. Energy Storage 2025, 140, 118981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Wang, H.; Wen, Q.; Xu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Shao, X.; Li, N. Controlled synthesis and thermal management studies of SiO2-Octadecane phase change nanocapsules. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 293, 113865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, S.; Miao, Y.; Wang, L.; Shi, J.; Wang, F.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, J. Development of octadecane/silica phase change nanocapsules for enhancing the thermal storage capacity of cement-based materials. J. Energy Storage 2024, 89, 111636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Emissions Reported to the UNFCCC and to the EU Greenhouse Gas Monitoring Mechanism, European Environment Agency (EEA). Available online: https://sdi.eea.europa.eu/catalogue/srv/eng/catalog.search#/metadata/3b7fe76c-524a-439a-bfd2-a6e4046302a2.

- Firman, L.O.M.; Ismail; Rahmalina, D.; Rahman, R.A. The Impact of Thermal Aging on the Degradation of Technical Parameter of a Dynamic Latent Thermal Storage System. Int. J. Thermofluids 2023, 19, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Recycled Aluminum Chips | Nanosilica (SiO2) | Expanded Graphite (EG)/ Graphene |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preparation Difficulty | Low (Mechanical) Method: Cleaning, sieving, and simple physical dispersion. Challenge: Settling issues (manageable with packing factor). | High (Chemical) Method: Sol-gel synthesis or in-situ polymerization. Challenge: Agglomeration of nanoparticles is a major issue; it requires ultrasonic dispersion or surface functionalization. | High (Complex) Method: Thermal expansion and vacuum impregnation. Challenge: A highly porous structure makes uniform PCM infiltration difficult without a vacuum; volume expansion creates handling issues. |

| Cost Effectiveness | Very high: Sourced from industrial waste (machining scrap). Material Cost: Very low. | Moderate (industrial fumed silica) to low (specialized/functionalized nano). Issue: High loading is required for a significant thermal boost, increasing the total cost. | Low (natural graphite) to moderate to high (expanded graphite/graphene). Issue: High processing costs make it prohibitive for large-scale building/thermal battery applications. |

| Environmental Friendliness | Excellent for circular economy practices. Energy/Carbon Footprint: Very low. Waste: Reduce landfilling. | Moderate energy/carbon footprint: Production involves energy-intensive electric furnaces. Risk: Nanoparticles pose potential inhalation/toxicity risks during handling and disposal. | Moderate to poor energy/carbon footprint: Graphitization requires extreme temperatures. Risk: EG production often uses strong acids and oxidizers. |

| PCM | Molar Mass (g/moL) | Density (g/cm3) | Melting Point (°C) | Viscosity (mPa·s) (20 °C) | Heat Capacity (J/(K·g)) | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-octadecane (C18H38) | 254.494 | 0.800 | 28–30 | 4.21 | 2.222 | 0.222 (solid) |

| Alloy | Si | Fe | Cu | Mn | Mg | Zn | Ti | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al 6060 [32] | 0.3–0.6 | 0.1–0.3 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.35–0.6 | <0.1 | <0.15 | R* |

| Al chips | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 0 | 0.05 | R* |

| Alloy | Density (Kg/m3) | Specific Heat Capacity (J/kg·K) | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al 6060 [33] | 2700 (at 20 °C) | 898 | 200–220 |

| Sample | Metal Content (Vol.%) |

|---|---|

| n-octadecane | 0 |

| n-octadecane-Al long | 7 |

| n-octadecane-Al short | 7.5 |

| Tpeak (°C) | Al Content wt.% | Heating Rates (K/min) |

|---|---|---|

| 34.8 | 0 (n-octadecane) | 9.97 |

| 30 | 7 (n-octadecane-Al-long) | 9.29 |

| 26.0 | 7.5 (n-octadecane-Al-short) | 8.75 |

| Sample | Density (g/cm3) | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) | Latent Heat of Fusion (kJ/kg) | Specific Heat Capacity (J/kg·K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-octadecane | 0.80 | 0.22 | 245 | 1908 |

| n-octadecane-Al-short | 0.92 | 0.44 | 191 | 1690 |

| n-octadecane-Al-long | 0.91 | 1.54 | 195 | 1700 |

| Sample | Effusivity (Ws1/2 m−2 K−1) | Percentage of Increase (%) | Diffusivity (m2/s) | Percentage of Increase (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-octadecane | 579 | - | 1.44 × 10−7 | - |

| n-octadecane Al-short | 827 | 43 | 2.83 × 10−7 | 96 |

| n-octadecane Al-long | 1543 | 166 | 9.95 × 10−7 | 590 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cobîrzan, N.; Thalmaier, G.; Mihaela, C.; Năsui, M.; Micu, D.D. Properties of n-Octadecane PCM Composite with Recycled Aluminum as a Thermal Enhancer. Materials 2025, 18, 5638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245638

Cobîrzan N, Thalmaier G, Mihaela C, Năsui M, Micu DD. Properties of n-Octadecane PCM Composite with Recycled Aluminum as a Thermal Enhancer. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245638

Chicago/Turabian StyleCobîrzan, Nicoleta, Gyorgy Thalmaier, Crețu Mihaela, Mircea Năsui, and Dan Doru Micu. 2025. "Properties of n-Octadecane PCM Composite with Recycled Aluminum as a Thermal Enhancer" Materials 18, no. 24: 5638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245638

APA StyleCobîrzan, N., Thalmaier, G., Mihaela, C., Năsui, M., & Micu, D. D. (2025). Properties of n-Octadecane PCM Composite with Recycled Aluminum as a Thermal Enhancer. Materials, 18(24), 5638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245638