A Photocatalytic TiO2 Coating with Optimized Mechanical Properties Shows Strong Antimicrobial Activity Against Foodborne Pathogens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of Experiments

2.2. Optimized-Coating Fabrication

2.3. Characterization of the Coating

2.3.1. Structural and Quality Analysis

2.3.2. Mechanical Analysis

2.3.3. Antimicrobial Activity

Coating Effects on Attached Bacteria

Coating Effects on Bacterial Biofilms

3. Results

3.1. Synthetic Factors Screening Experiment

3.1.1. Microstructure and Crystal Phase

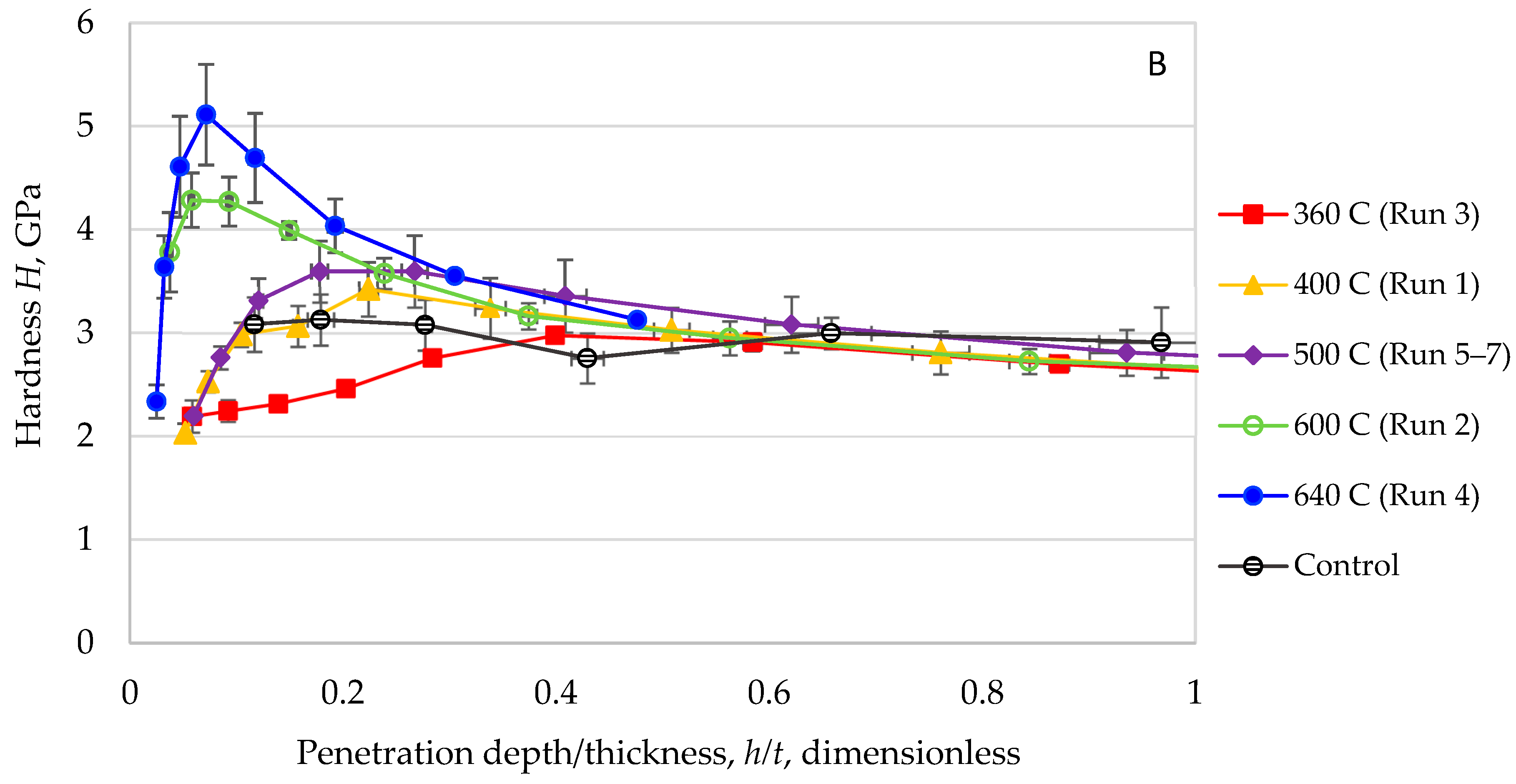

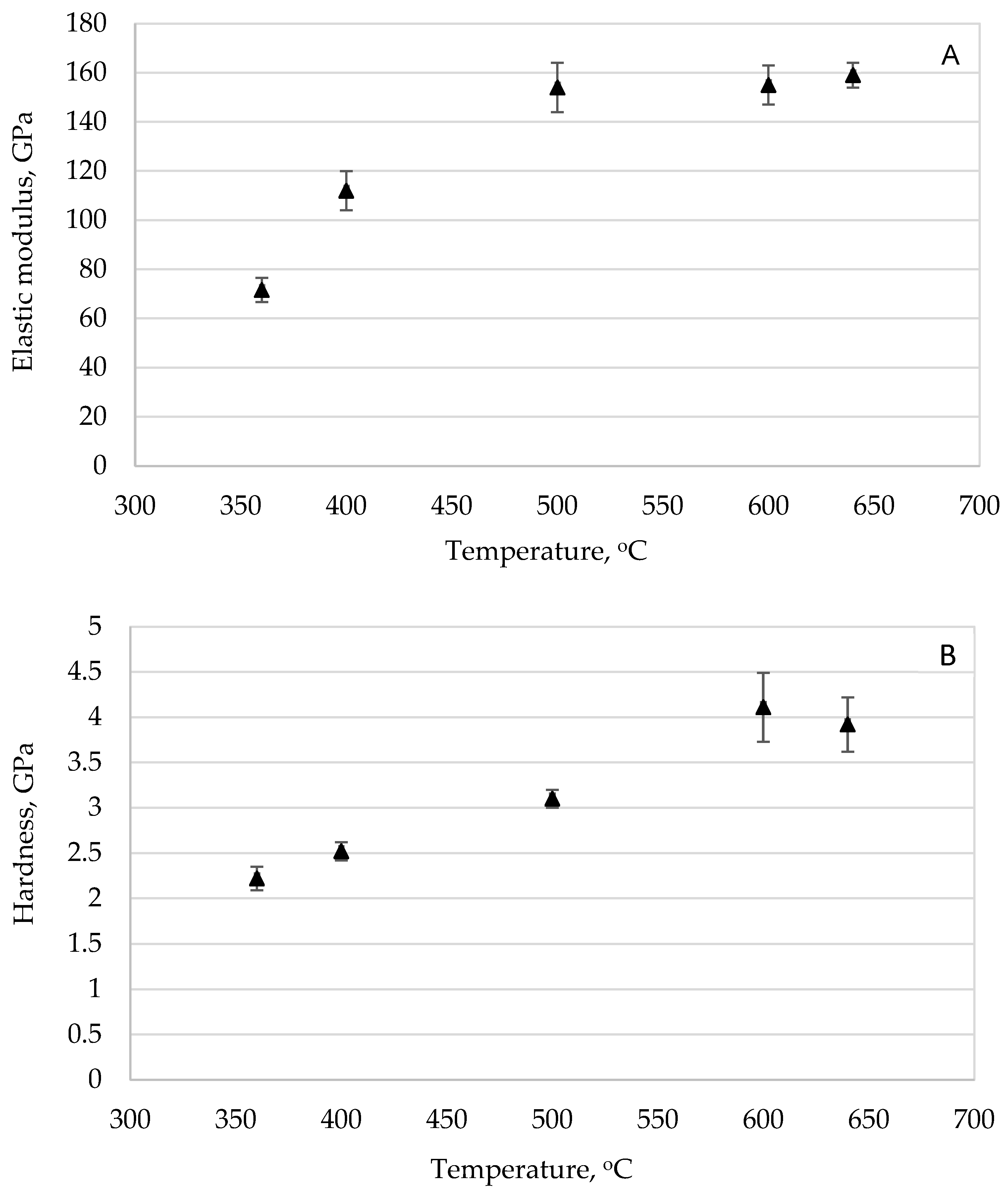

3.1.2. Nanoindentation Hardness and Elastic Modulus

3.2. Trends Determination Experiment

3.3. Optimization of Hardness, Elastic Modulus, and Photocatalytic Activity

3.4. Optimized Coating’s Structural and Quality Analysis

3.4.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

3.4.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

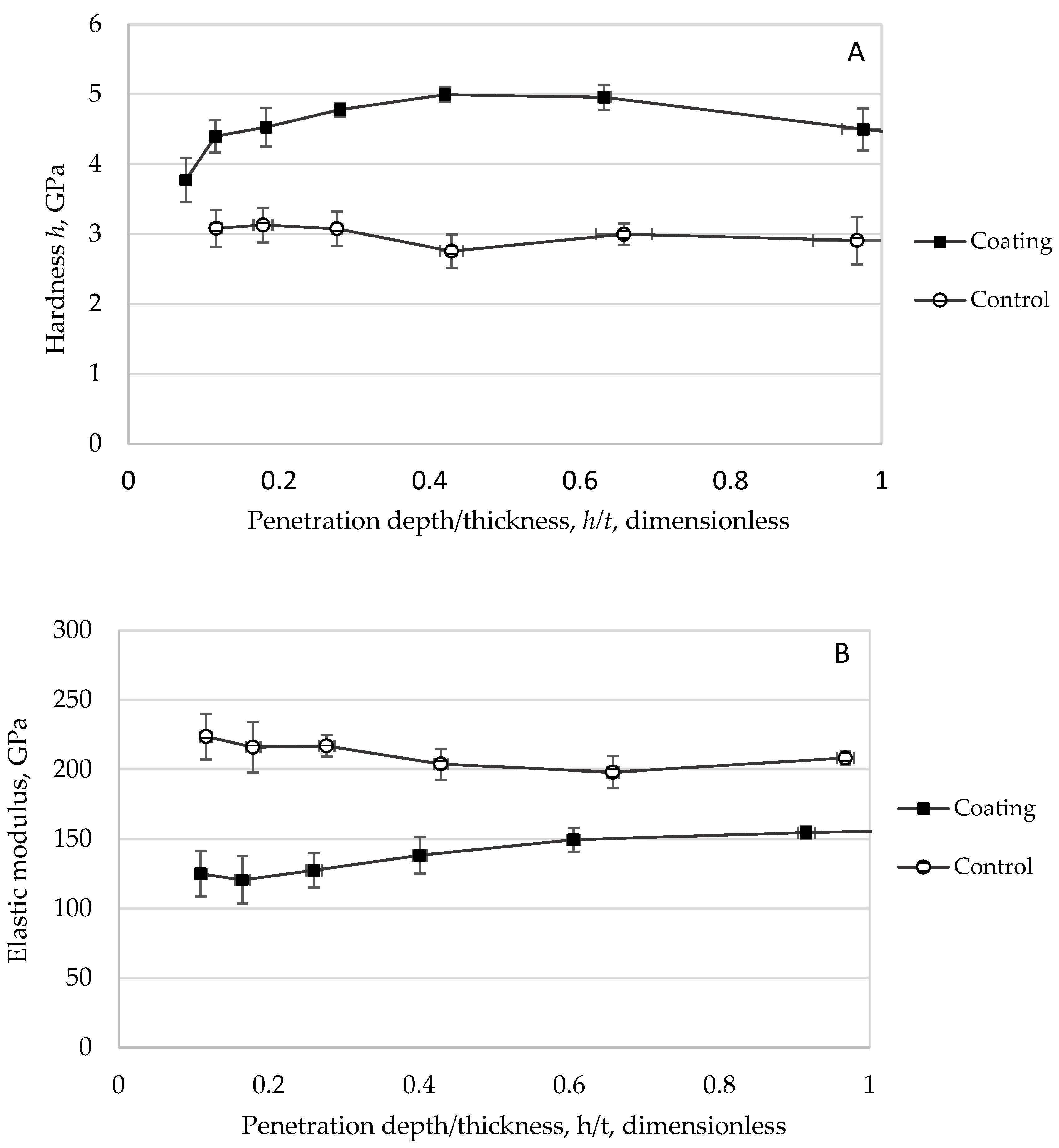

3.4.3. Hardness and Elastic Modulus

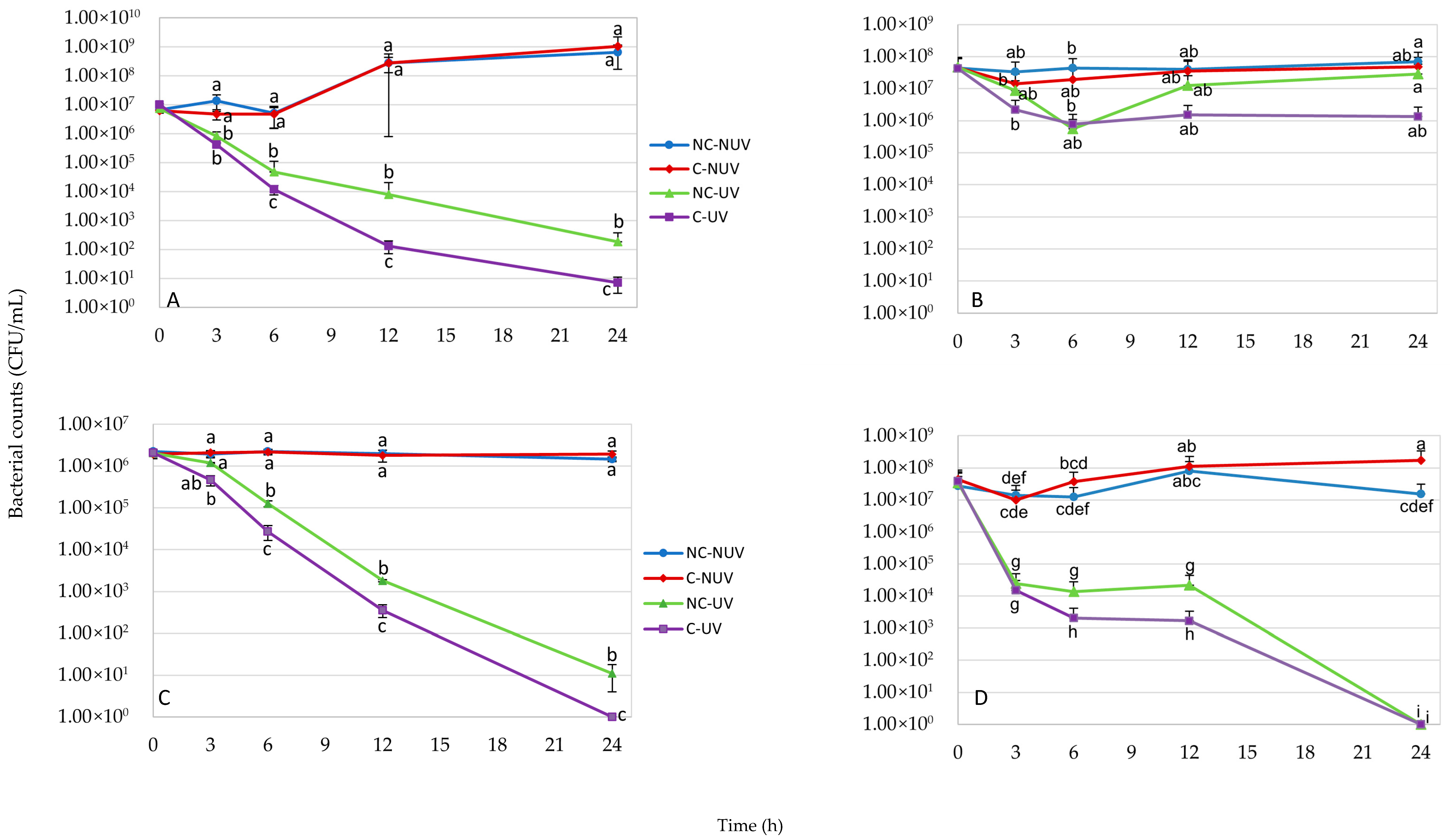

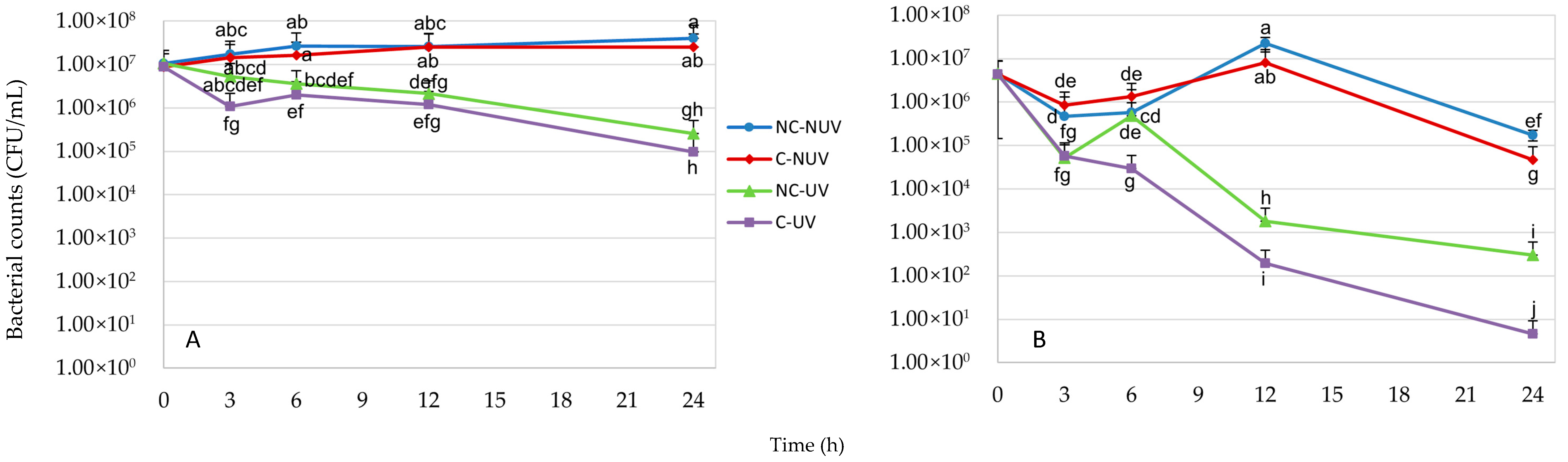

3.5. Coating Effects on Pathogenic Bacteria

3.5.1. Effects of Protocol 1 and 2 Coatings on Attached Cells

3.5.2. Effects of Protocol 2 Coatings on Pathogenic Biofilms

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. World Health Organization, Food Safety, Key Facts. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safety (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- CDC. Burden of Foodborne Illness: Findings. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/2011-foodborne-estimates.html (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- FDA. Food and Drug Administration, Report of the Occurrence of Foodborne Illness Risk Factors in Fast Food and Full-Service Restaurants, 2013–2014. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/117509/download?attachment (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- CDC. Food Safety. 2017. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/food-safety/prevention/index.html (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Hussain, M.; Dawson, C. Economic impact of food safety outbreaks on food businesses. Foods 2013, 2, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Dominguez, E.; Nguyen, P.H.; Hunt, H.K.; Mustapha, A. Antimicrobial coatings for food contact surfaces: Legal framework, mechanical properties, and potential applications. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 1825–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamisse, E.; Firmesse, O.; Christieans, S.; Chassaing, D.; Carpentier, B. Impact of cleaning and disinfection on the non-culturable and culturable bacterial loads of food-contact surfaces at a beef processing plant. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 158, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.L.; Pires, A.C.S.; Behaine, J.J.S.; Araújo, E.A.; de Andrade, N.J.; de Carvalho, A.F. Effect of cleaning treatment on adhesion of Streptococcus agalactiae to milking machine surfaces. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 1868–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemmireddy, V.K.; Hung, Y.-C. Effect of binder on the physical stability and bactericidal property of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanocoatings on food contact surfaces. Food Control 2015, 57, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemmireddy, V.K.; Hung, Y.-C. Using photocatalyst metal oxides as antimicrobial surface coatings to ensure food safety-opportunities and challenges. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Niu, J.; Chen, Y. Mechanism of photogenerated reactive oxygen species and correlation with the antibacterial properties of engineered metal-oxide nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 5164–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemmireddy, V.K.; Hung, Y.-C. Photocatalytic TiO2 coating of plastic cutting board to prevent microbial cross-contamination. Food Control 2017, 77, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, R.; Ishiguro, H.; Yao, Y.; Kajioka, J.; Fujishima, A.; Sunada, K.; Minoshima, M.; Hashimoto, K.; Kubota, Y. Photocatalytic inactivation of influenza virus by titanium dioxide thin film. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2012, 11, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilja, M.; Forsgren, J.; Welch, K.; Åstrand, M.; Engqvist, H.; Strømme, M. Photocatalytic and antimicrobial properties of surgical implant coatings of titanium dioxide deposited through cathodic arc evaporation. Biotechnol. Lett. 2012, 34, 2299–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bideau, M.; Claudel, B.; Dubien, C.; Faure, L.; Kazouan, H. On the “Immobilization” of titanium dioxide in the photocatalytic oxidation of spent waters. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 1995, 91, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, G.C.; Espinosa-Medina, M.A.; Martinez-Villafane, A.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, J.G.; Castano, V.M. Study of ceramic and hybrid coatings produced by the sol-gel method for corrosion protection. Open Corros. J. 2009, 2, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villatte, G.; Massard, C.; Descamps, S.; Sibaud, Y.; Forestier, C.; Awitor, K.O. Photoactive TiO2 antibacterial coating on surgical external fixation pins for clinical application. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 3367–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çomaklı, O.; Yazıcı, M.; Kovacı, H.; Yetim, T.; Yetim, A.F.; Çelik, A. Tribological and electrochemical properties of TiO2 films produced on cp-ti by sol-gel and silar in bio-simulated environment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 352, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, R.W. Mechanical Properties of Ceramics and Composites: Grain and Particle Effects; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Visai, L.; De Nardo, L.; Punta, C.; Melone, L.; Cigada, A.; Imbriani, M.; Arciola, C.R. Titanium oxide antibacterial surfaces in biomedical devices. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2011, 34, 929–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Mekprasart, W.; Pecharapa, W. Anatase/rutile TiO2 composite prepared via sonochemical process and their photocatalytic activity. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 6159–6165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsellami, L.; Dappozze, F.; Fessi, N.; Houas, A.; Guillard, C. Highly photocatalytic activity of nanocrystalline TiO2 (anatase, rutile) powders prepared from TiCl4 by sol–gel method in aqueous solutions. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 113, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendavid, A.; Martin, P.J.; Takikawa, H. Deposition and modification of titanium dioxide thin films by filtered arc deposition. Thin Solid Film. 2000, 360, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafedh, D.; Kaouther, K.; Ahmed, B.C.L. Multi-Property Improvement of TiO2-WO3 mixed oxide films deposited on 316l stainless steel by electrophoretic method. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 326, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Dominguez, E. Photocatalytic Antimicrobial Coating for Food Contact Surfaces. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA, July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Dominguez, E.; Nguyen, P.; Hylen, A.; Maschmann, M.R.; Mustapha, A.; Hunt, H.K. Design and characterization of mechanically stable, nanoporous TiO2 thin film antimicrobial coatings for food contact surfaces. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 251, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, H.; Mustapha, A.; Torres-Dominguez, E. Antimicrobial Coating for Food Contact Surfaces. US Non-Provisional Patent Application: 17/499,374, 12 October 2021. Available online: https://patents.justia.com/patent/20220112381 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Lazic, Z.R. Design of Experiments in Chemical Engineering: A Practical Guide; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Xiang, Y.; Vlassak, J.J. Novel technique for measuring the mechanical properties of porous materials by nanoindentation. J. Mater. Res. 2006, 21, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Atefyekta, S.; Ercan, B.; Karlsson, J.; Taylor, E.; Chung, S.; Webster, T. Antimicrobial performance of mesoporous titania thin films: Role of pore size, hydrophobicity, and antibiotic release. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, A.M. Nanotechnology Cookbook: Practical, Reliable and Jargon-Free Experimental Procedures, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Cripps, A.C. Nanoindentation, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Giuliani, F.; Atkinson, A. Surface quality improvement of porous thin films suitable for nanoindentation. Acta Mater. 2015, 99, 5720–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çomaklı, O.; Yetim, T.; Çelik, A. The effect of calcination temperatures on wear properties of TiO2 coated CP-Ti. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 246, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, C.J.; Sherer, G.W. Sol-Gel Science: The Physics and Chemistry of Sol-Gel Processing; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Urade, V.N.; Bollmann, L.; Kowalski, J.D.; Tate, M.P.; Hillhouse, H.W. Controlling interfacial curvature in nanoporous silica films formed by evaporation-induced self-assembly from nonionic surfactants. II. Effect of processing parameters on film structure. Langmuir 2007, 23, 4268–4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Run | Synthetic Factor | Coating Thickness, nm | Response | Crystallite Size, nm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol | Ti:EO 1 | taging, h | rpm | Tsintering, °C | Hardness, GPa | Elastic Modulus, GPa | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 6000 | 400 | 608 ± 33 | 0.527 ± 0.02 | 39.9 ± 2.8 | 15.54 |

| 2 | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 2000 | 600 | 688 ± 51 | 1.28 ± 0.21 | 118 ± 7 | 18.32 |

| 3 | 1 | 0.5 | 240 | 6000 | 400 | 905 ± 82 | 0.394 ± 0.18 | 60.6 ± 7.9 | 18.32 |

| 4 | 1 | 0.5 | 240 | 2000 | 600 | 1103 ± 94 | 1.03 ± 0.26 | 171 ± 3 | 16.70 |

| 5 | 2 | 1.2 | 240 | 6000 | 600 | 1156 ± 122 | 4.27 ± 0.45 | 188 ± 23 | 24.15 |

| 6 | 2 | 1.2 | 240 | 2000 | 400 | 1750 ± 198 | 2.66 ± 0.21 | 168 ± 9 | 17.71 |

| 7 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 6000 | 600 | 825 ± 76 | 5.32 ± 0.61 | 221 ± 26 | 19.95 |

| 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 2000 | 400 | 854 ± 84 | 2.48 ± 0.21 | 153 ± 14 | 22.68 |

| Run | Synthetic Factor | Response | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol | Ti:EO 1 | taging, h | rpm | Tsintering, °C | Coating Thickness, nm | Hardness, GPa | Elastic Modulus, GPa | |

| 1 | 2 | 1.2 | 1 | 2000 | 400 | 988 ± 11 | 2.52 ± 0.10 | 112 ± 8 |

| 2 | 2 | 1.2 | 1 | 2000 | 600 | 1005 ± 8 | 4.11 ± 0.38 | 155 ± 8 |

| 3 | 2 | 1.2 | 1 | 2000 | 360 | 1102 ± 10 | 2.22 ± 0.13 | 72 ± 5 |

| 4 | 2 | 1.2 | 1 | 2000 | 640 | 1021 ± 13 | 3.92 ± 0.30 | 159 ± 5 |

| 5 | 2 | 1.2 | 1 | 2000 | 500 | 895 ± 18 | 3.10 ± 0.08 | 154 ± 15 |

| 6 | 2 | 1.2 | 1 | 2000 | 500 | 1054 ± 14 | 3.16 ± 0.10 | 144 ± 10 |

| 7 | 2 | 1.2 | 1 | 2000 | 500 | 1073 ± 12 | 2.77 ± 0.06 | 153 ± 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres Domínguez, E.; Chenggeer, F.; Mao, L.; Maschmann, M.R.; Hunt, H.K.; Mustapha, A. A Photocatalytic TiO2 Coating with Optimized Mechanical Properties Shows Strong Antimicrobial Activity Against Foodborne Pathogens. Materials 2025, 18, 5640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245640

Torres Domínguez E, Chenggeer F, Mao L, Maschmann MR, Hunt HK, Mustapha A. A Photocatalytic TiO2 Coating with Optimized Mechanical Properties Shows Strong Antimicrobial Activity Against Foodborne Pathogens. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245640

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres Domínguez, Eduardo, Fnu Chenggeer, Liang Mao, Matthew R. Maschmann, Heather K. Hunt, and Azlin Mustapha. 2025. "A Photocatalytic TiO2 Coating with Optimized Mechanical Properties Shows Strong Antimicrobial Activity Against Foodborne Pathogens" Materials 18, no. 24: 5640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245640

APA StyleTorres Domínguez, E., Chenggeer, F., Mao, L., Maschmann, M. R., Hunt, H. K., & Mustapha, A. (2025). A Photocatalytic TiO2 Coating with Optimized Mechanical Properties Shows Strong Antimicrobial Activity Against Foodborne Pathogens. Materials, 18(24), 5640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245640