Effects of Dust Addition on the Reactivity and High-Temperature Compressive Strength of Ferro-Coke

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Sample Preparation

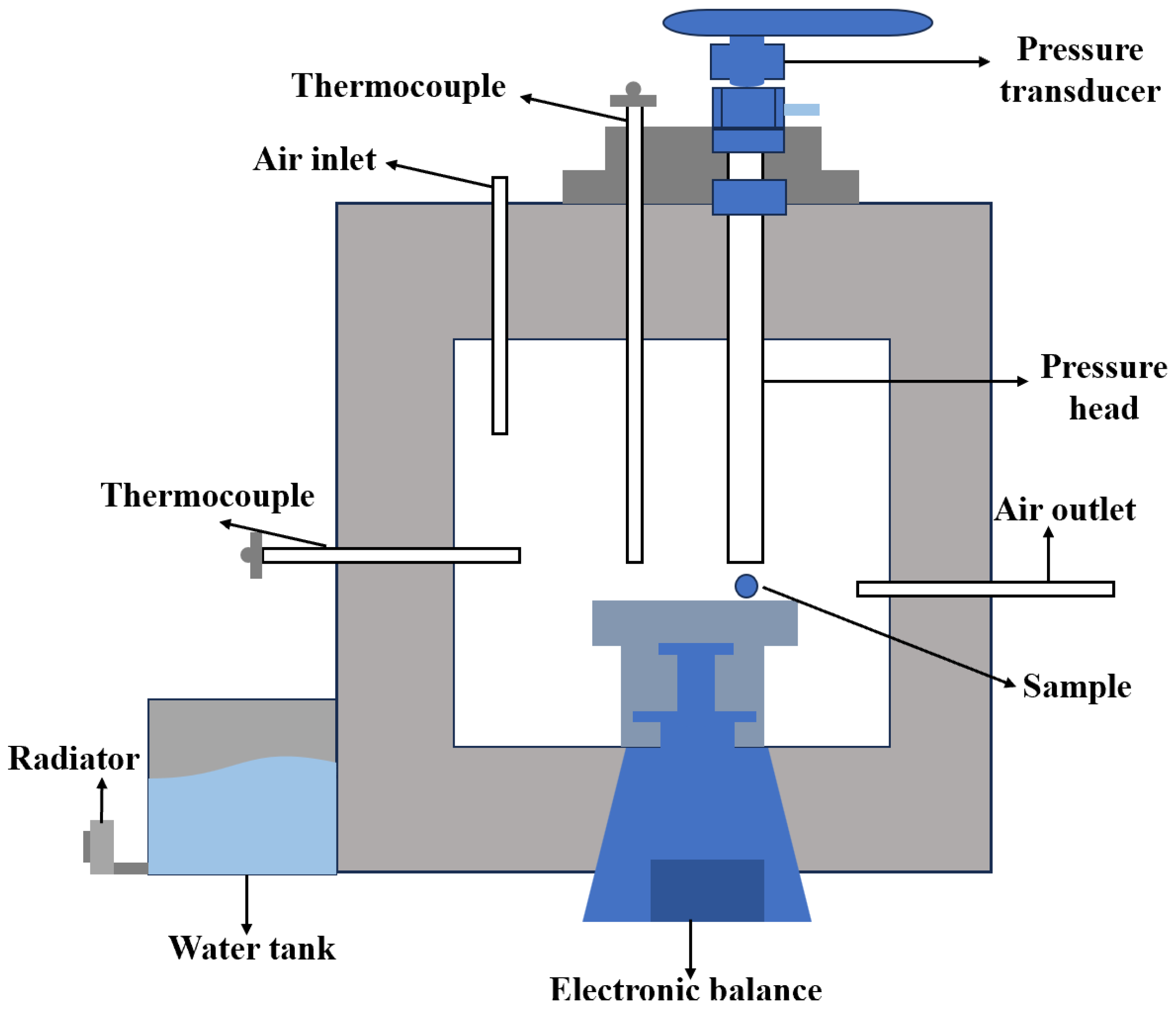

2.2.2. Carbonization and Gasification Tests

2.2.3. High-Temperature Strength Test

2.2.4. 3D CT Analysis

2.2.5. Ultra-Precise 3D Microscopy

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Reactivity of Ferro-Coke

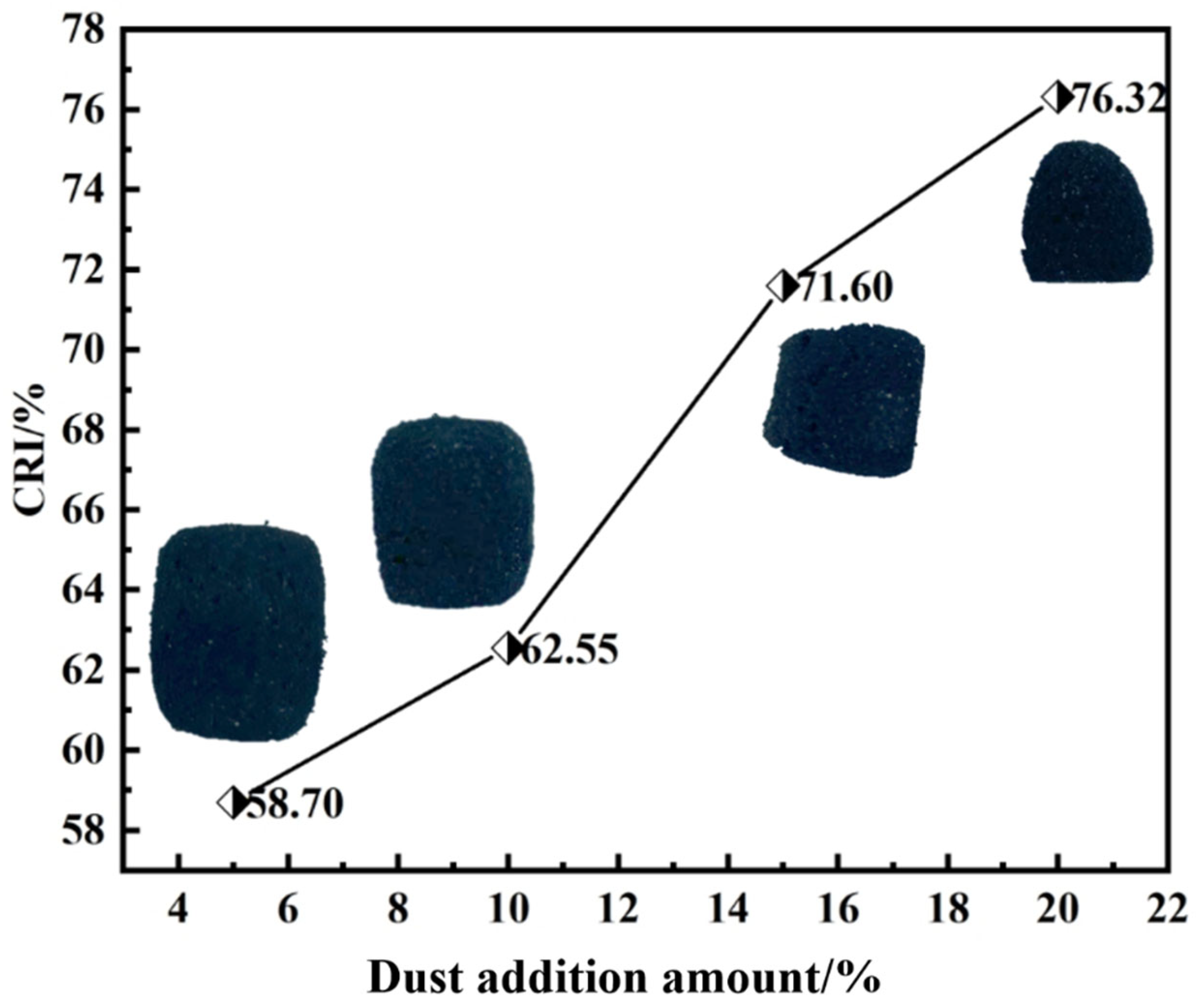

3.1.1. Effect of Iron-Carbon Containing Dust Addition

3.1.2. Effect of Gasification Temperature

3.2. High-Temperature Compressive Strength of Ferro-Coke

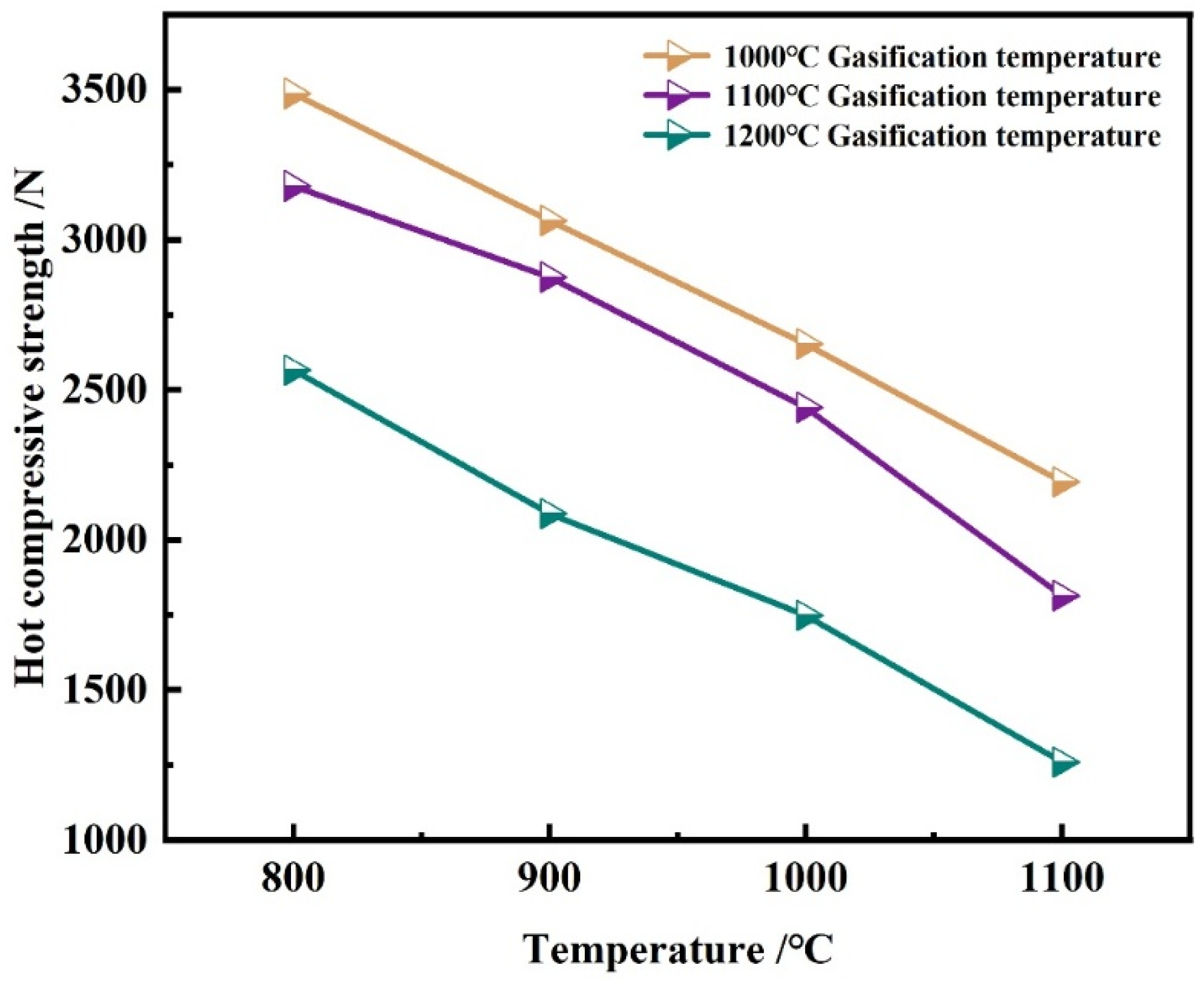

Effect of Gasification Temperature

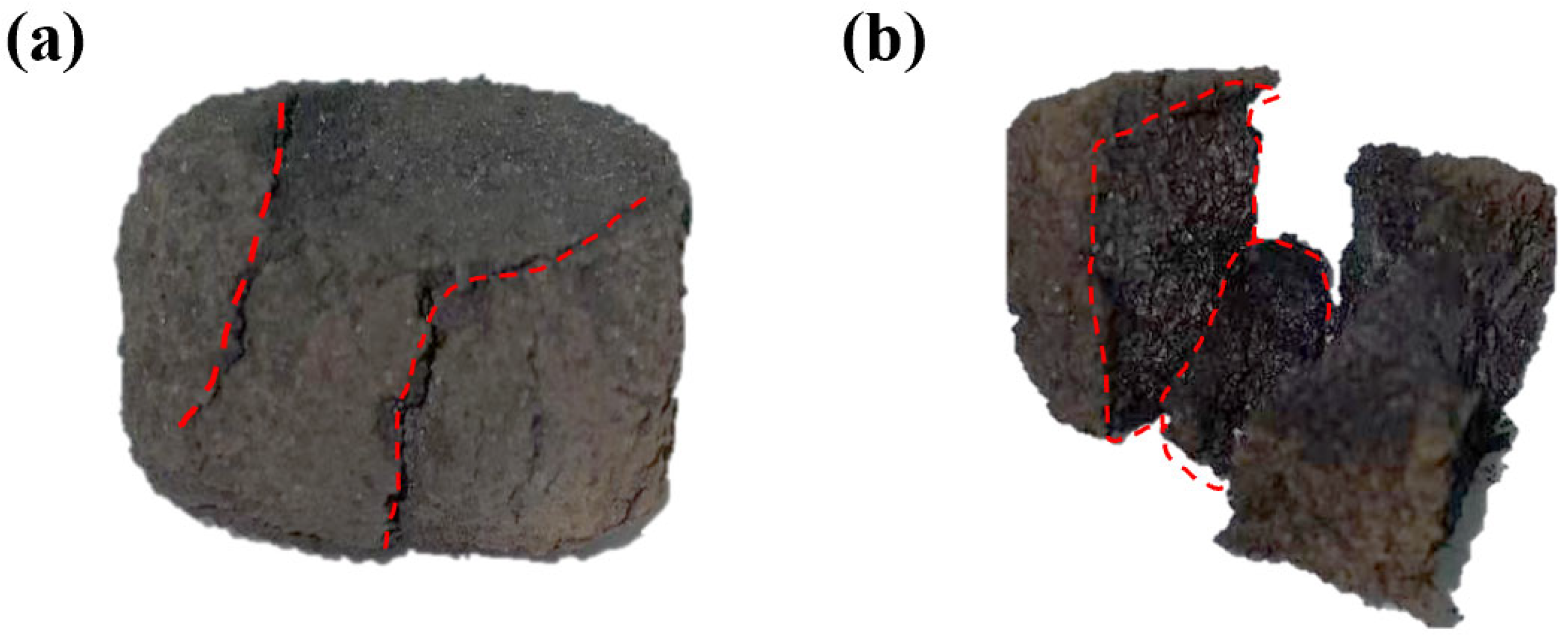

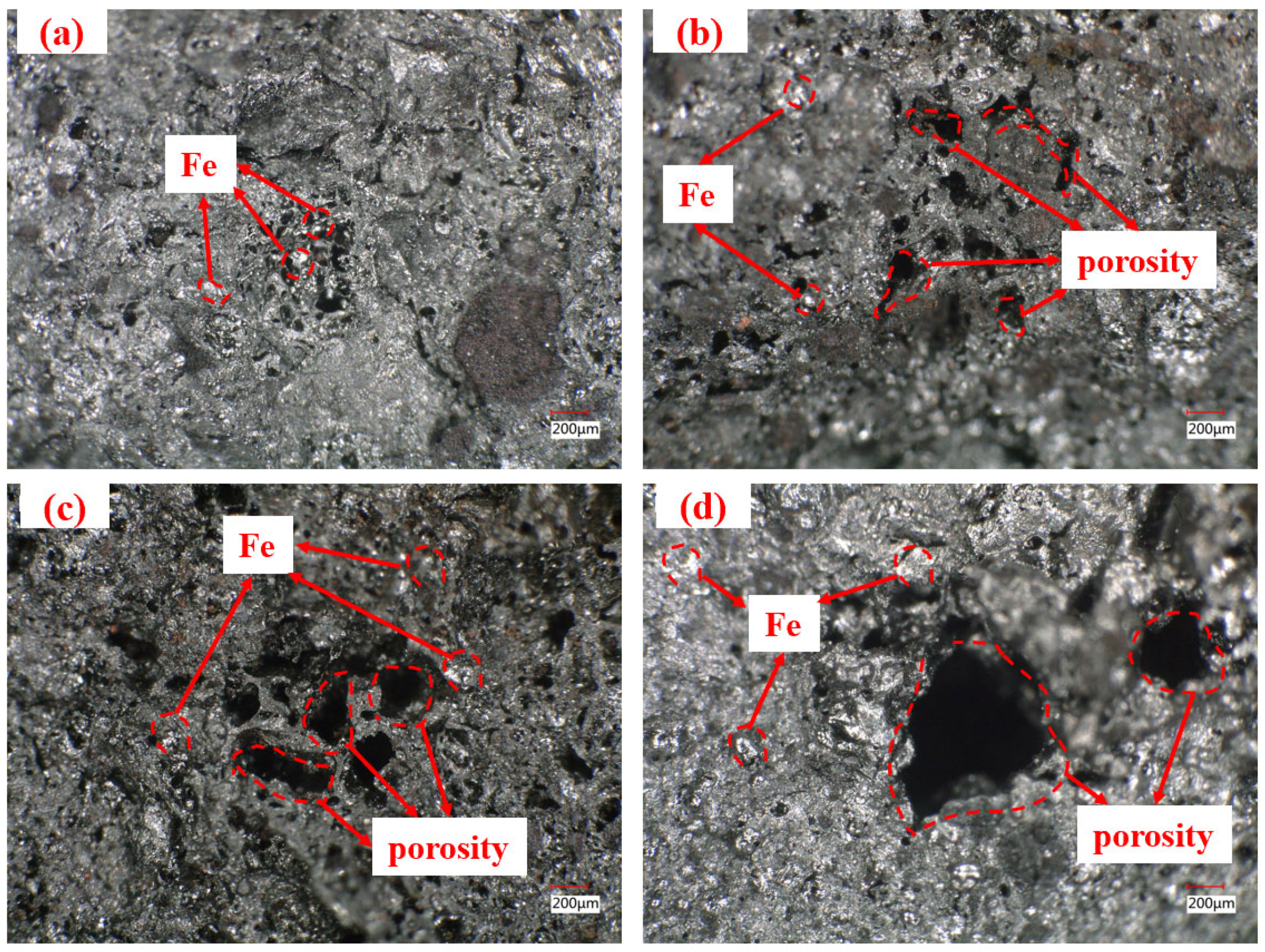

3.3. Microstructure of Ferro-Coke After Gasification and Thermal Cracking

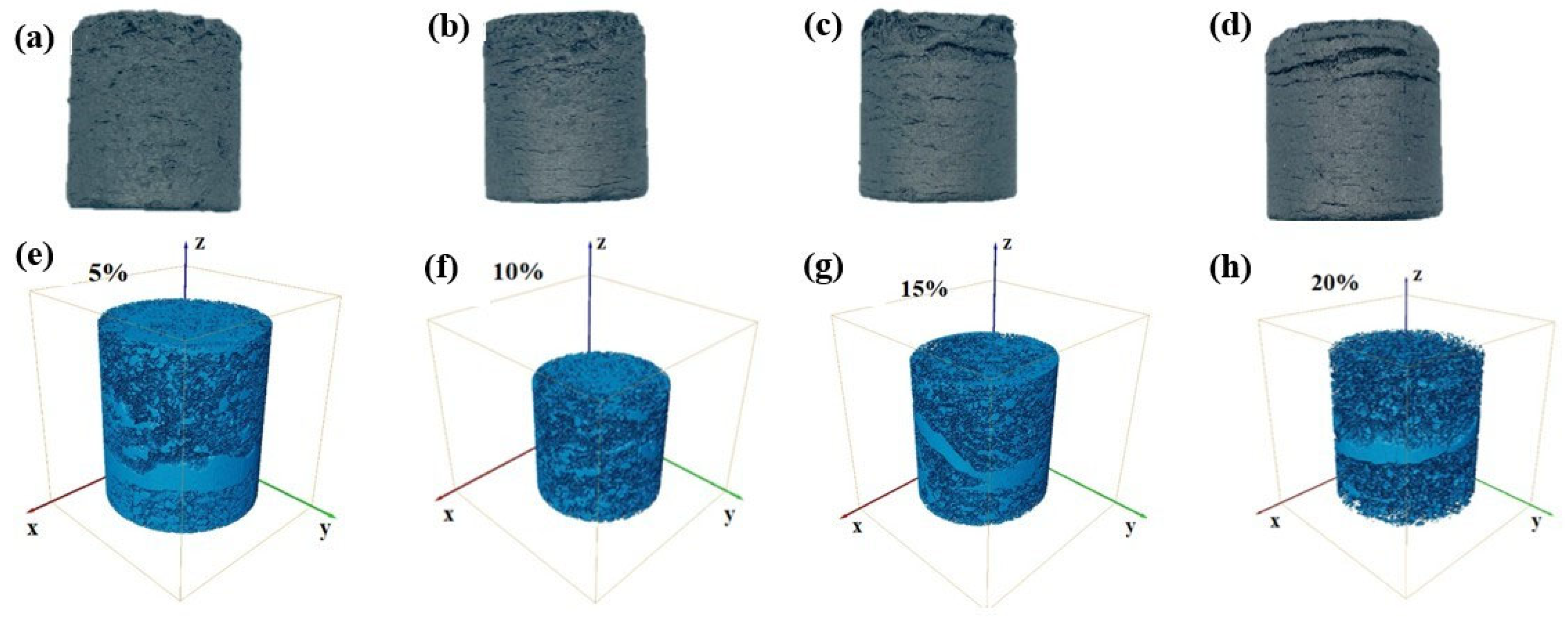

3.3.1. Effect of Iron-Carbon-Containing Dust Addition

3.3.2. Effect of Gasification Temperature

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Increasing the ICD addition elevates the CRI of ferro-coke. As the ICD addition increases from 5% to 20%, the CRI rises from 58.70% to 76.32%, while the high-temperature strength of ferro-coke after gasification decreases from 3260 N to 1954 N at 800 °C. Iron and zinc in the dust catalyze gasification, intensify internal erosion, and thereby reduce high-temperature strength.

- (2)

- Increasing the gasification temperature also raises CRI. When the gasification temperature increases from 1000 °C to 1200 °C, the CRI increases from 51.95% to 65.51%, accompanied by a decrease in high-temperature strength. Higher gasification temperatures enhance reactivity, increase porosity, and diminish the high-temperature strength.

- (3)

- At 5–10% ICD addition and a gasification temperature of 1100 °C, ferro-coke exhibits comparable strengths, indicating a balance between metallic iron contributing to the load-bearing skeleton and its suppression of coal expansibility. The high-temperature strength reduction in ferro-coke stems from the following two factors: (i) Zn catalyzes carbon gasification; (ii) Zn volatilizes at high temperature, generating additional porosity, enlarging specific surface area, and further accelerating carbon gasification.

- (4)

- Based on the comprehensive analysis of high-temperature compressive strength, reactivity, and structural evolution, an ICD addition of 10 wt.% appears to offer the best balance. Within this range, the beneficial catalytic effect on gasification is present without causing excessive structural degradation or zinc-induced weakening, thereby optimally mitigating high-temperature fragmentation for blast furnace application.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Q.; Wang, J.S.; She, X.F.; Xue, Q.G.; Guo, Z.C.; Wang, G.; Zuo, H.B. Principles and support technologies of low-carbon ironmaking for blast furnace. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 211, 115363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Pang, K.; Jiang, Z.; Meng, X.; Gu, Z. Development and problems of fluidized bed ironmaking process: An overview. J. Sustain. Metall. 2023, 9, 1399–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Pang, K.; Barati, M.; Meng, X. Hydrogen-based reduction technologies in low-carbon sustainable ironmaking and steelmaking: A review. J. Sustain. Metall. 2024, 10, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, X.; Bao, J.; Hao, Q.; Zheng, H.; Xu, R. Role of iron ore in enhancing gasification of iron coke: Structural evolution, influence mechanism and kinetic analysis. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2025, 32, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, R.; Shi, J.; Dong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ye, Y. Effect of Biochar Addition on the Strength Properties of Metallurgical Dust Briquettes. J. Sustain. Metall. 2025, 11, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-J.; Cao, M.-H.; Zhang, J.-L.; Xu, R.-S.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Yu, J.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-C. Synergistic reaction behavior of pyrolysis and reduction of briquette prepared by weakly caking coal and metallurgical dust. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2023, 30, 1367–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Dai, B.; Wang, W.; Schenk, J.; Xue, Z. Effect of iron ore type on the thermal behaviour and kinetics of coal-iron ore briquettes during coking. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 173, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chu, M.; Bao, J.; Liu, Z.; Tang, J.; Long, H. Experimental study on impact of iron coke hot briquette as an alternative fuel on isothermal reduction of pellets under simulated blast furnace conditions. Fuel 2020, 268, 117339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-T.; Chu, M.-S.; Zhao, W.; Liu, Z.-G. Effect of process parameters on the compressive strength of iron coke hot briquette. J. Northeast. Univ. Nat. Sci. 2016, 37, 810. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.-T.; Chu, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Liu, Z.; Tang, J.; Ying, Z. Research on the Post-reaction Strength of Iron Coke Hot Briquette Under Different Conditions. JOM 2018, 70, 1929–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, W.; Chu, M.; Liu, Z.; Tang, J.; Ying, Z. Effects of coal and iron ore blending on metallurgical properties of iron coke hot briquette. Powder Technol. 2018, 328, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, W.; Zhang, H.; Bi, X.; Shi, S. Impact of Potassium on Gasification Reaction and Post-Reaction Strength of Ferro-coke. ISIJ Int. 2017, 57, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.-S.; Deng, S.-L.; Zheng, H.; Wang, W.; Song, M.-M.; Xu, W.; Wang, F.-F. Influence of initial iron ore particle size on CO2 gasification behavior and strength of ferro-coke. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2020, 27, 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.-Z.; Sun, C.-Q.; Bi, X.-G. Experimental research of effect of iron ore powders ratio on ferro-coke quality. Iron Steel 2014, 49, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.-X.; Bi, X.-G.; Shi, S.-Z.; Wu, Q.; Sun, C.; Ma, Y.; Cheng, X.; Li, P. Influence of iron ore addition into coal blend for coke-making on coke properties. J. Wuhan Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2014, 37, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Zheng, H.; Wang, W.; Schenk, J.; Xue, Z. Influence of Iron Minerals on the Volume, Strength, and CO2 Gasification of Ferro-coke. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 12118–12127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhang, J.; Conejo, A.; Wu, B.; Wang, L.; Xu, Q. Effect of Zinc-Containing Dust on the Thermal Behavior and Kinetics of Coal–Dust Briquettes During Co-coking Process. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2025, 56, 6575–6591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, A.; Yamazaki, Y.; Matsuo, S.; Saito, Y.; Matsushita, Y.; Aoki, H.; Hamaguchi, M. Effect of HPC (Hyper-coal) on Strength of Ferro-coke during Caking Temperature. ISIJ Int. 2017, 57, 1524–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornostayev, S.; Härkki, J. Mechanism of Physical Transformations of Mineral Matter in the Blast Furnace Coke with Reference to Its Reactivity and Strength. Energy Fuels 2006, 20, 2632–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, Y.; Nomura, S.; Arima, T.; Kato, K. Effects of Coal Inertinite Size on Coke Strength. ISIJ Int. 2008, 48, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulos, N.; Dukino, R.; Sakurovs, R. The strength controlling properties of coke and their relationship to tumble drum indices and coal type. ACARP Proj. C 2002, C, 9060. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T31391-2015; Ultimate Analysis of Coal. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhang, J.; Conejo, A.; Wu, B.; Yang, Y.; Dong, Y. Effect of pore structure and dust ratio on mechanical and metallurgical properties of ferro-coke: Based on CT and 3D reconstruction technology. Powder Technol. 2026, 467, 121445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Zhao, R.; Kitagawa, K.; Wang, K.; Guo, Z.; Xie, Y. Study on utilizing zinc and lead-bearing metallurgical dust as sulfur absorbent during briquette combustion. Energy 2005, 30, 2251–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Proximate Analysis | Ultimate Analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fc/% | Ash/% | Vad/% | C | H | N | S | Oa | |

| RM | 21.57 | 12.13 | 66.30 | 77.14 | 4.28 | 2.48 | 1.328 | 2.74 |

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | TiO2 | K2O | Na2O | P2O5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM | 2.906 | 35.822 | 11.321 | 2.858 | 0.319 | 2.832 | 0.755 | 0.344 | 1.043 |

| TFe | CaO | SiO2 | MgO | Al2O3 | K | Na | ZnO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32.30 | 8.06 | 8.87 | 4.4 | 1.32 | 1.56 | 1.27 | 12.46 |

| Addition Amount of ICD | Gasification Temperature | High-Temperature Strength Test Temperature |

|---|---|---|

| 5% | 1100 °C | 800 °C/900 °C/1000 °C/ 1100 °C |

| 10% | 25 °C/1000 °C/1100 °C/1200 °C | |

| 15% | 1100 °C | |

| 20% | 1100 °C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, R.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, B. Effects of Dust Addition on the Reactivity and High-Temperature Compressive Strength of Ferro-Coke. Materials 2025, 18, 5637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245637

Wang R, Li S, Yang Y, Xu R, Zhang J, Zeng Y, Zhang Y, Wu B. Effects of Dust Addition on the Reactivity and High-Temperature Compressive Strength of Ferro-Coke. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245637

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Rongrong, Siqi Li, Yongsheng Yang, Runsheng Xu, Jianliang Zhang, Yu Zeng, Yuchen Zhang, and Bin Wu. 2025. "Effects of Dust Addition on the Reactivity and High-Temperature Compressive Strength of Ferro-Coke" Materials 18, no. 24: 5637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245637

APA StyleWang, R., Li, S., Yang, Y., Xu, R., Zhang, J., Zeng, Y., Zhang, Y., & Wu, B. (2025). Effects of Dust Addition on the Reactivity and High-Temperature Compressive Strength of Ferro-Coke. Materials, 18(24), 5637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245637