Laser Directed Energy Deposition of Inconel625 to Ti6Al4V Heterostructure via Nonlinear Gradient Transition Interlayers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

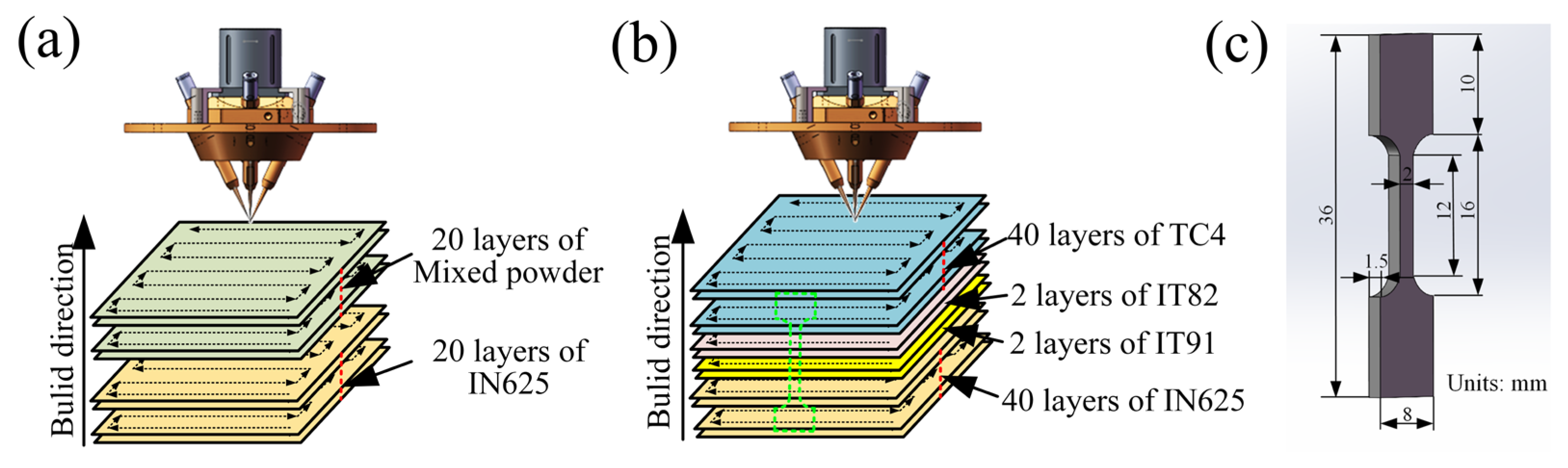

2.2. The Manufacturing of the IN625/TC4 HS

2.3. Characterization Methods

3. Results and Discussion

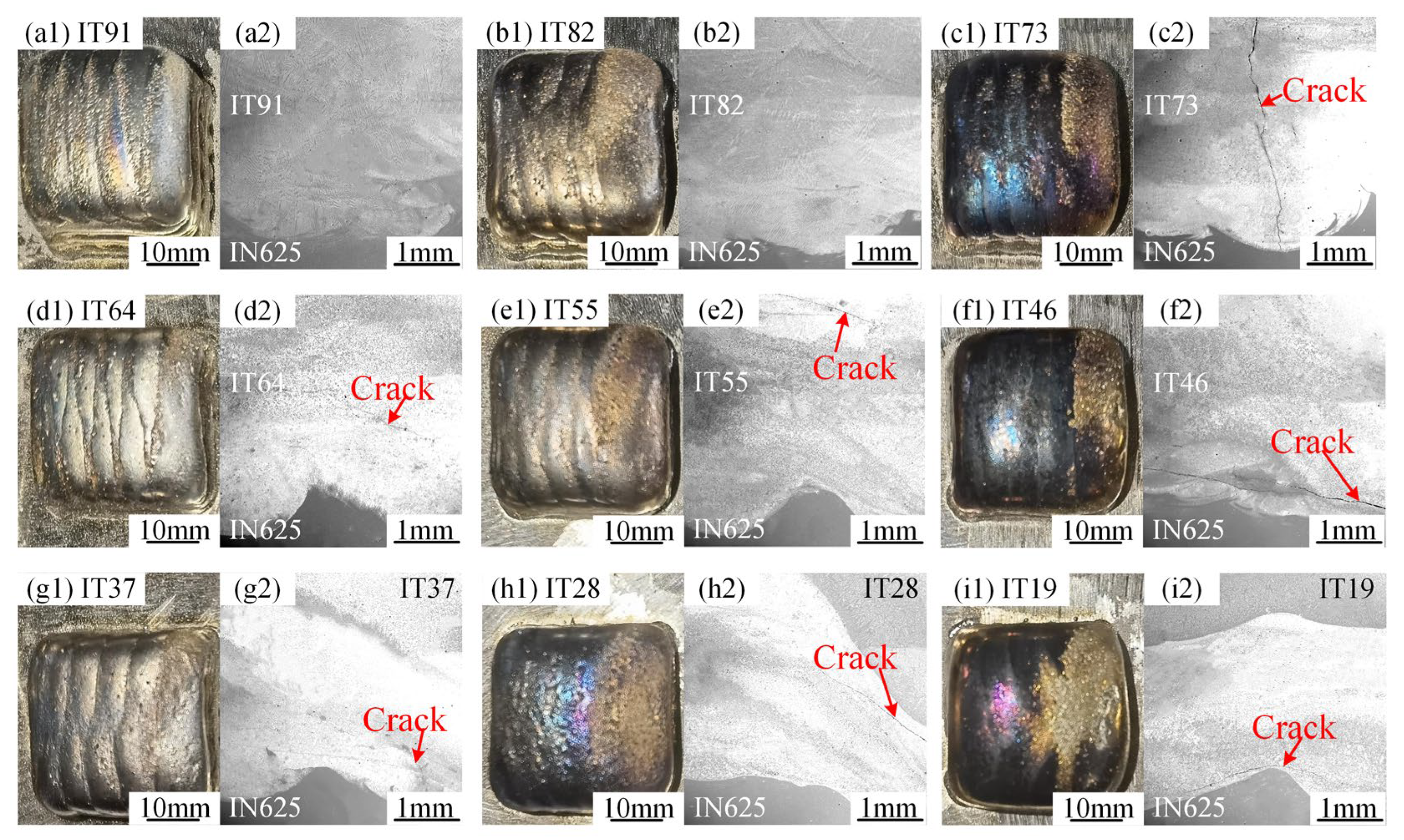

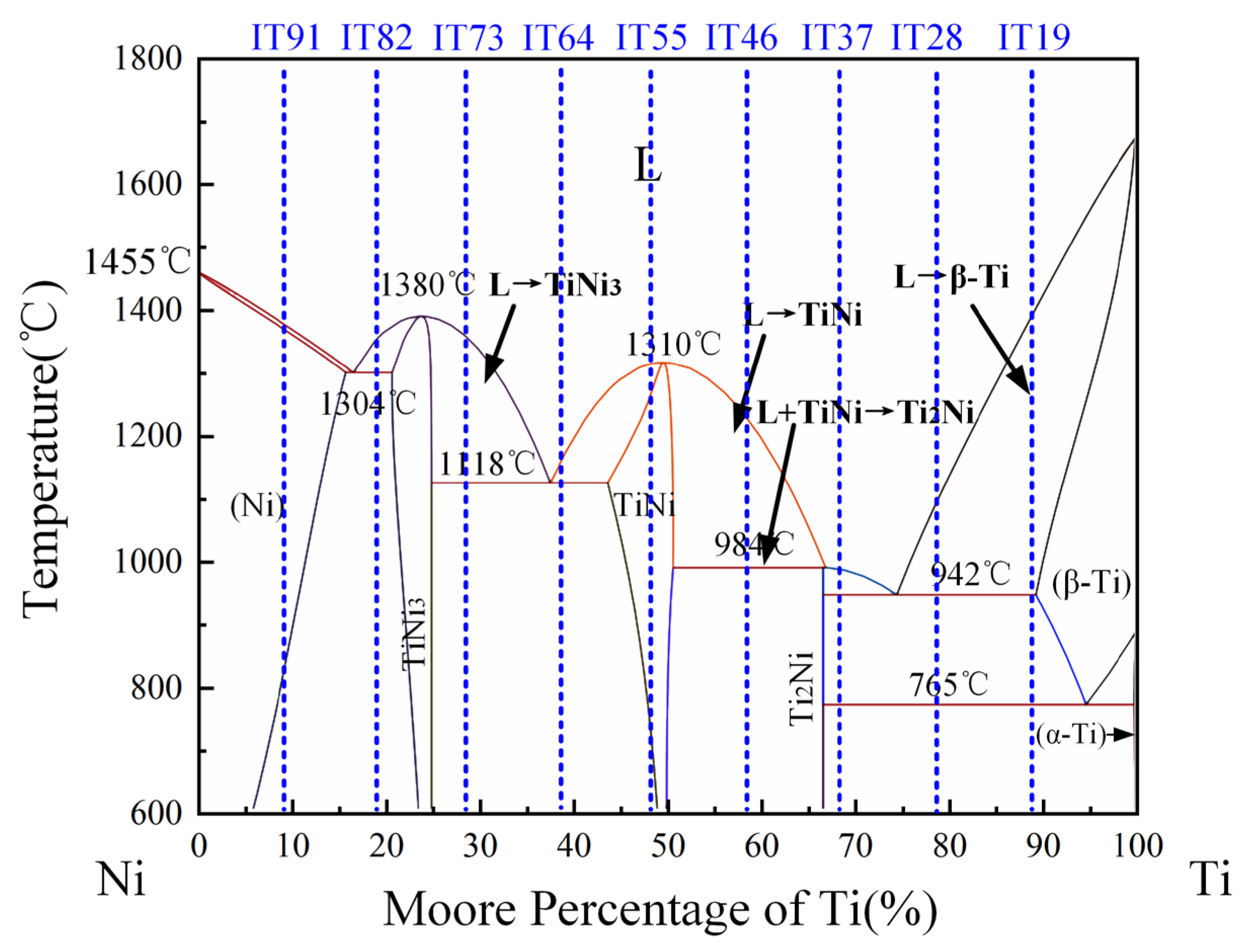

3.1. Selection of Transition Layers

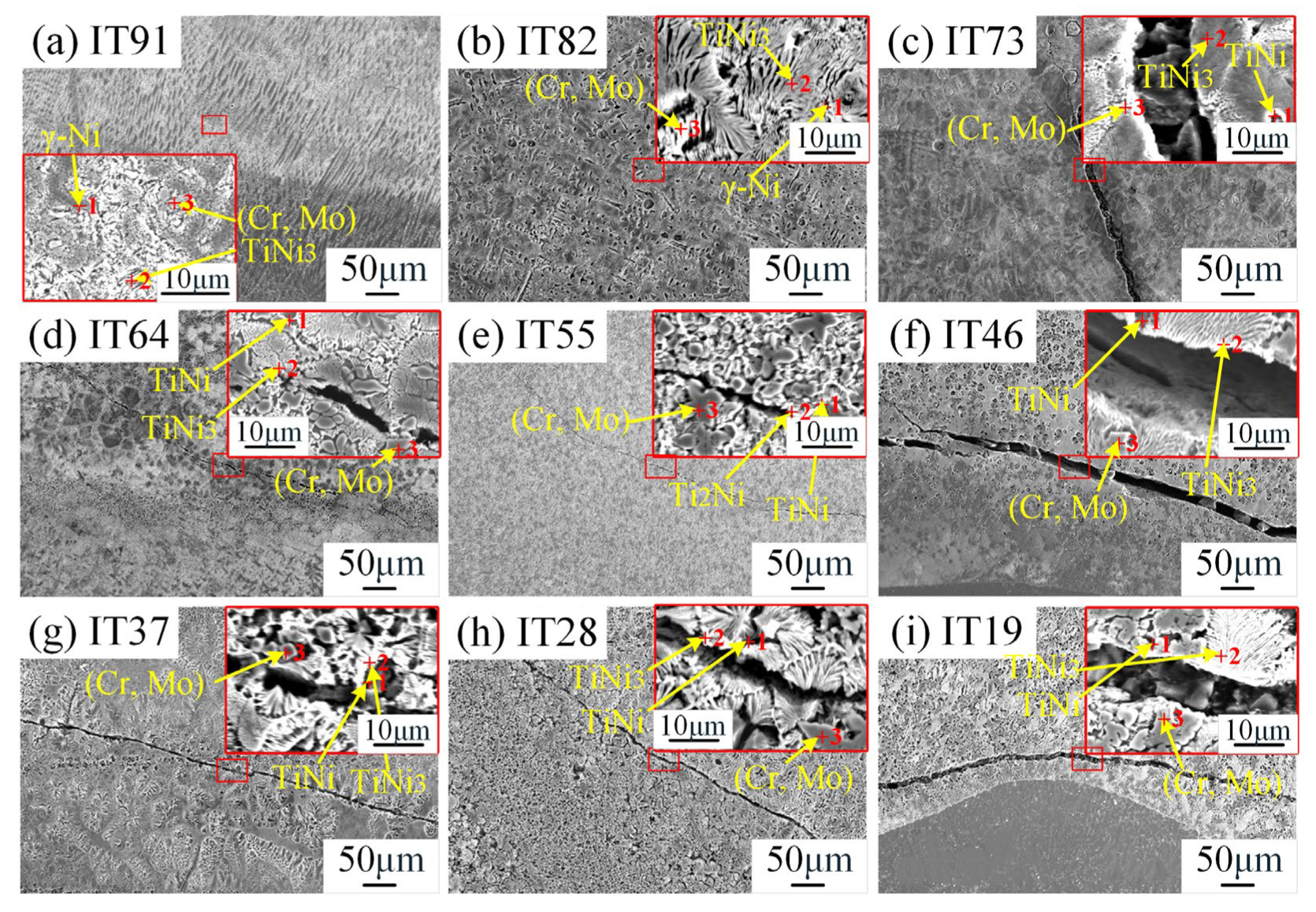

3.2. Microstructure Analysis

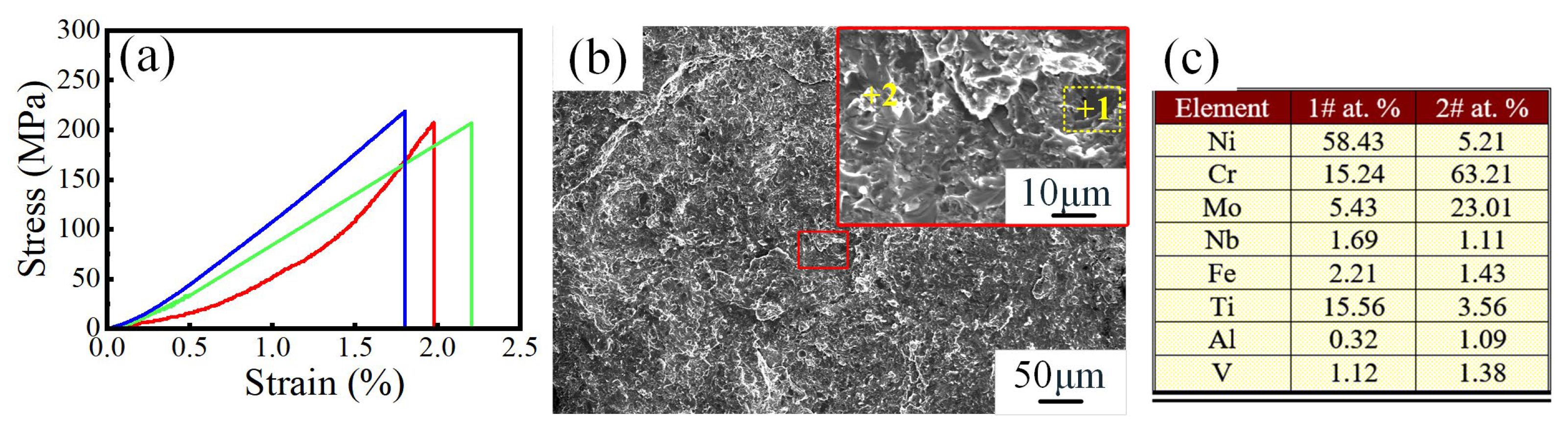

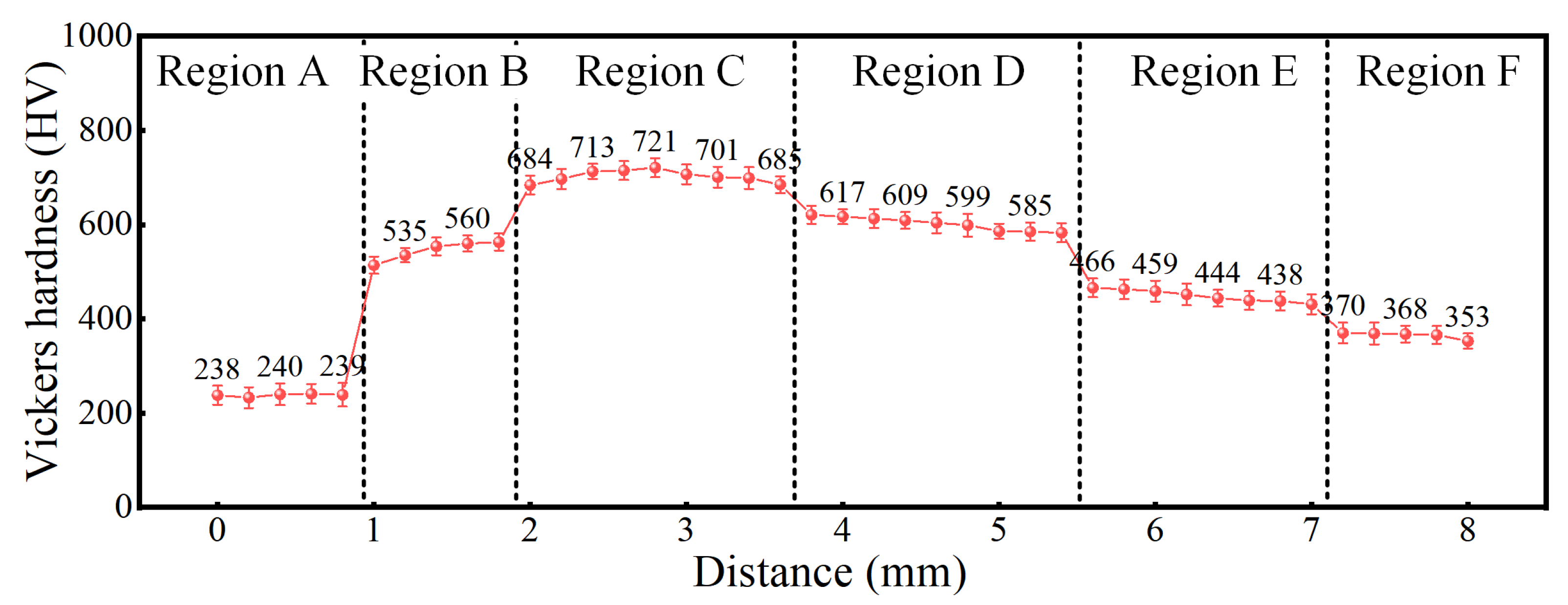

3.3. Mechanical Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.; Yuan, D.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wei, C. Effect of deposition sequence on interface characteristics of IN718/CuSn10 horizontal bimetallic structures via laser directed energy deposition. Mater. Design 2025, 255, 114085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, X.; Yuan, D.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Wei, C. Interfacial characterization and cracking behavior of NiTi/AlSi12 bimetallic structures fabricated by multi-material laser additive manufacturing. Mater. Charact. 2025, 224, 115075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Yan, Y.; Chen, J.; Liang, C.; Bi, G.; Zhao, C. Microstructure and mechanical property evolution of 316L/18Ni300 bimetallic structure manufactured by laser powder bed fusion. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 929, 148141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, R.S.; Jhavar, S. Multi-wire additive manufacturing: A comprehensive review on materials, microstructure, methodological advances, and applications. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsten, J.; Angelina, M.; Sergej, G.; Ömer, Ü.; Andrey, G.; Michael, R. Laser Welding of SLM-Manufactured Tubes MadeofIN625 and IN718. Materials 2019, 12, 2967. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, S.M.; Krishna, K.M.; Sharma, S.; Joshi, S.S.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Banerjee, R.; Dahotre, N.B. Thermo-mechanical process variables driven microstructure evolution during additive friction stir deposition of IN625. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 80, 103958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guowei, L.; Yinshuang, W.; Yahong, L.; Pengxiang, G.; Xinyu, L.; Wencai, X.; Dawei, Y. Microstructure and mechanical properties of laser welded Ti-6Al-4V (TC4) titanium alloy joints. Opt. Laser. Technol. 2024, 170, 110320. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, T.; Jiang, T.; Dai, G.; Guo, Y.; Sun, Z.; Chang, H.; Han, Y.; Li, S.; Alexandrov, I.V. The microstructure evolution of TC4-(TiB + TiC)/TC4 laminated composites by laser melting deposition. Mater. Charact. 2023, 197, 112665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chang, Y.; Gu, L.; Luo, Y.; Ge, B. Study of microstructure of nickel-based superalloys at high temperatures. Scripta Mater. 2017, 126, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodor, A.B.; Mădălin, D. The Influence of Alloying Elements on the Hot Corrosion Behavior of Nickel-Based Superalloys. Materials 2025, 18, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farabi, E.; He, X.; Obersteiner, D.; Musi, M.; Neves, J.; Klein, T.; Primig, S. Synergistic precipitation reactions in a novel high-temperature Ti-alloy. Scripta Mater. 2025, 259, 116543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, X.; Ren, C.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Liu, Q.; Shi, H.; Chan, K.C.; Song, N.; Xiang, D.; Sun, H.; et al. Enhanced strength and ductility in α-titanium alloys through in-situ alloying via additive manufacturing. J. Alloy. Compd. 2025, 1027, 180598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Qin, J.; Cheng, K.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Dong, P. Design and Performance of a Compact Air-Breathing Jet Hybrid-Electric Engine Coupled with Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 613205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Fan, M.; Huo, X.; Ma, N.; Lu, F. The heterogeneous microstructure of laser welded joint and its effect on mechanical properties for dissimilar 9Cr steel and alloy 617. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 1094–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Duan, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhong, S. The Study on Mechanical Strength of Titanium-Aluminum Dissimilar Butt Joints by Laser Welding-Brazing Process. Materials 2019, 12, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dildin, A.N.; Gerasimov, V.Y.; Zaitseva, O.V. The Structure of Multi-Layer Composite Material Obtained by the Method of Diffusion Welding. Mater. Sci. Forum 2019, 946, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Tian, W.-T.; Yang, Q.-H.; Yang, J.; Wang, K.-S. Inertia radial friction welding of Ti60(near-α)/TC18(near-β) bimetallic components: Interfacial bonding mechanism, heterogenous microstructure and mechanical properties. Mater. Charact. 2024, 208, 113598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, A.D.; Farzad, K. Underwater submerged dissimilar friction-stir welding of AA5083 aluminum alloy and A441 AISI steel. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 102, 4383–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Song, X.; Hu, S.; Fu, W.; Chen, X.; Cao, J. Evaluation of mechanical properties and vacuum brazing for TiAl/GH3536 hetero-honeycomb sandwich ultrathin-walled structure. Weld. World 2022, 66, 1999–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Liu, G.; Xie, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, J.; Li, A.; Jin, Q. Interfacial microstructure evolution and brazing properties of the vacuum-brazed QAl9-4/1Cr17Ni2 joints with a novel Cu-Mn-Ag-Ni-Zn filler metal. Vacuum 2025, 233, 113960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yu, Y.; Li, L.; Zhou, H. Underlying mechanism of interfacial evolution in laminate IN625/TC4 composites for enhanced mechanical properties. Mater. Charact. 2024, 210, 113795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Lu, L.; Xin, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, G.; Cai, Y.; Tian, Y. Microstructure and mechanical properties of a novel functionally graded material from Ti6Al4V to Inconel 625 fabricated by dual wire + arc additive manufacturing. J. Alloy. Compd. 2022, 903, 163981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Cory, J.G.; David, P.F.; Susmita, B.; Amit, B. Additive manufacturing of Ti-Ni bimetallic structures. Mater. Design 2022, 215, 110461. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Lu, H.; Liang, Y.; Luo, K.; Lu, J. Integrated manufacturing method for compressor blisks: LDED Ti65 on sheet Ti-6Al-4V. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 932, 148266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Xue, H.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, G.; Xu, F.; Melentiev, R.; Newman, S.; Yu, N. Review of online quality control for laser directed energy deposition (LDED) additive manufacturing. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2025, 45, 062005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Shen, J.; Hu, S.; Geng, K.; Xu, N. 316L/Ti6Al4V bimetallic structure with Ni interlayer fabricated by laser melting deposition. Mater. Lett. 2022, 321, 132451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, L.; Lyu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhan, X. Temperature variation and mass transport simulations of invar alloy during continuous-wave laser melting deposition. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 152, 108163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xu, D.; Geng, S.; Fan, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, F. Mechanical properties, corrosion behavior and cytotoxicity of Ti-6Al-4V alloy fabricated by laser metal deposition. Mater. Charact. 2021, 179, 111302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P.; Elangovan, S.; Mohanraj, R.; Ramakrishna, J.R. A review on properties of Inconel 625 and Inconel 718 fabricated using direct energy deposition. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 7892–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debroy, T.; Wei, H.L.; Zuback, J.S.; Mukherjee, T.; Elmer, J.W.; Milewski, J.O.; Beese, A.M.; Wilson-Heid, A.; De, A.; Zhang, W. Additive manufacturing of metallic components—Process, structure and properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 92, 112–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.T.; Weng, F.; Sui, S.; Chew, Y.; Bi, G. Progress and perspectives in laser additive manufacturing of key aeroengine materials. Int. J. Mach. Tool. Manuf. 2021, 170, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, D.N.; Alireza, K.; Gabriele, I.; Kate, T.Q.N.; David, H. Additive manufacturing (3D printing): A review of materials, methods, applications and challenges. Compos. Part. B Eng. 2018, 143, 172–196. [Google Scholar]

- Bonny, O.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Additive manufacturing of Inconel 718—Ti6Al4V bimetallic structures. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 22, 844–851. [Google Scholar]

- Domack, M.S.; Baughman, J.M. Development of nickel-titanium graded composition components. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2005, 11, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, Z.; Yu, C.; Liu, C.; Zhan, Y. Finite element analysis for residual stress of TC4/Inconel718 functionally gradient materials produced by laser additive manufacturing. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 152, 108146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Xie, G.; Chang, H. Microstructural evolution and high temperature resistance of functionally graded material Ti-6Al-4V/Inconel 718 coated by directed energy deposition-laser. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 848, 156255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, N.; Liu, X.; Jing, Z.; Xu, G.; Xing, F. Laser melting deposition of Inconel625/Ti6Al4V bimetallic structure with Cu/V interlayers. Mater. Res. Express 2023, 10, 076516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.-O.; Helander, T.; Höglund, L.; Shi, P.F.; Sundman, B. Thermo-Calc and DICTRA, Computational tools for materials science. Calphad 2002, 26, 273–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbio, L.D.; Otis, R.A.; Borgonia, J.P.; Dillon, R.P.; Shapiro, A.A.; Liu, Z.; Beese, A.M. Additive manufacturing of a functionally graded material from Ti-6Al-4V to Invar: Experimental characterization and thermodynamic calculations. Acta. Mater. 2017, 127, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Jiang, X.; Sun, H.; Song, T.; Mo, D.; Li, X. Interfacial reaction and microstructure investigation of 4J36/Ni/Cu/V/TC4 diffusion-bonded joints. Mater. Lett. 2021, 305, 130809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.E.; Otis, R.A.; Borgonia, J.P.; Borgonia, J.P.; Suh, J.-O.; Dillon, R.P.; Shapiro, A.A.; Hofmann, D.C.; Liu, Z.-K.; Beese, A.M. Functionally graded material of 304L stainless steel and inconel 625 fabricated by directed energy deposition: Characterization and thermodynamic modeling. Acta. Mater. 2016, 108, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Xu, N.; Jing, Z.; Xu, G.; Xing, F. Effect of Solution Temperature on Microstructure and Properties of Ti6Al4V by Laser-Directed Energy Deposition. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 32, 1515–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mass Fraction (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IN625 | C | Fe | Al | Mo | Nb | Cr | Si | Ti | Ni |

| 0.05 | 4.01 | 0.30 | 8.85 | 3.59 | 22.1 | 0.02 | 0.21 | Bal. | |

| TC4 | C | Fe | Al | O | H | N | V | Ti | |

| 0.007 | 0.206 | 6.26 | 0.082 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 4.08 | Bal. | ||

| Name | Material Composition (vol.%) | Laser Power (W) | Scan Speed (mm/min) | Layer Thickness (mm) | Protective Gas Flow Rate (L/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IN625 | 100%IN625 | 1800 | 720 | 0.6 | 15 |

| IT91 | 90%IN625 + 10%TC4 | 1850 | 720 | 0.6 | 15 |

| IT82 | 80%IN625 + 20%TC4 | 1900 | 720 | 0.6 | 15 |

| IT73 | 70%IN625 + 30%TC4 | 1950 | 720 | 0.6 | 15 |

| IT64 | 60%IN625 + 40%TC4 | 2000 | 720 | 0.6 | 15 |

| IT55 | 50%IN625 + 50%TC4 | 2050 | 720 | 0.6 | 15 |

| IT46 | 40%IN625 + 60%TC4 | 2100 | 720 | 0.6 | 15 |

| IT37 | 30%IN625 + 70%TC4 | 2150 | 720 | 0.6 | 15 |

| IT28 | 20%IN625 + 80%TC4 | 2200 | 720 | 0.6 | 15 |

| IT19 | 10%IN625 + 90%TC4 | 2250 | 720 | 0.6 | 15 |

| TC4 | 100%TC4 | 2300 | 720 | 0.6 | 15 |

| Location | Ni | Cr | Mo | Nb | Fe | Ti | Al | V | Deduced Phases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IT91 | a1 | 59.78 ± 1.54 | 20.43 ± 1.03 | 6.56 ± 0.53 | 2.14 ± 0.04 | 3.21 ± 0.07 | 3.21 ± 0.09 | 2.43 ± 0.04 | 2.24 ± 0.03 | γ-Ni |

| a2 | 62.89 ± 2.36 | 6.78 ± 0.66 | 4.32 ± 0.12 | 3.21 ± 0.07 | 1.01 ± 0.02 | 18.21 ± 0.98 | 2.01 ± 0.03 | 1.57 ± 0.06 | TiNi3 | |

| a3 | 8.91 ± 0.78 | 67.01 ± 2.54 | 16.25 ± 0.99 | 1.01 ± 0.04 | 1.13 ± 0.02 | 2.46 ± 0.06 | 1.59 ± 0.04 | 1.64 ± 0.03 | (Cr, Mo) | |

| IT82 | b1 | 55.21 ± 1.87 | 20.31 ± 1.01 | 8.34 ± 0.87 | 3.21 ± 0.09 | 4.11 ± 0.18 | 5.96 ± 0.59 | 1.53 ± 0.06 | 1.33 ± 0.02 | γ-Ni |

| b2 | 60.32 ± 2.56 | 7.01 ± 0.19 | 5.59 ± 0.13 | 2.21 ± 0.09 | 2.59 ± 0.08 | 19.32 ± 1.01 | 1.54 ± 0.02 | 1.42 ± 0.06 | TiNi3 | |

| b3 | 10.21 ± 0.33 | 64.32 ± 2.98 | 18.53 ± 0.98 | 1.01 ± 0.02 | 2.31 ± 0.06 | 1.21 ± 0.03 | 1.03 ± 0.02 | 1.38 ± 0.02 | (Cr, Mo) | |

| IT73 | c1 | 50.71 ± 1.98 | 1.59 ± 0.09 | 1.06 ± 0.06 | 1.54 ± 0.05 | 1.32 ± 0.05 | 41.21 ± 1.87 | 1.55 ± 0.02 | 1.02 ± 0.03 | TiNi |

| c2 | 60.21 ± 2.33 | 6.64 ± 0.23 | 3.21 ± 0.15 | 1.09 ± 0.05 | 1.11 ± 0.06 | 23.48 ± 1.01 | 1.05 ± 0.03 | 3.21 ± 0.04 | TiNi3 | |

| c3 | 4.22 ± 0.07 | 65.32 ± 2.68 | 18.43 ± 1.03 | 1.61 ± 0.09 | 1.59 ± 0.02 | 5.03 ± 0.04 | 2.21 ± 0.04 | 1.59 ± 0.03 | (Cr, Mo) | |

| IT64 | d1 | 49.32 ± 2.01 | 2.54 ± 0.08 | 1.11 ± 0.08 | 1.32 ± 0.06 | 1.11 ± 0.03 | 42.21 ± 1.87 | 1.11 ± 0.06 | 1.28 ± 0.09 | TiNi |

| d2 | 58.24 ± 1.68 | 9.21 ± 0.25 | 4.54 ± 0.16 | 2.25 ± 0.13 | 2.21 ± 0.16 | 20.34 ± 1.23 | 1.54 ± 0.09 | 1.67 ± 0.07 | TiNi3 | |

| d3 | 9.24 ± 0.19 | 60.24 ± 1.94 | 20.21 ± 1.01 | 5.32 ± 0.13 | 1.59 ± 0.12 | 1.21 ± 0.14 | 1.01 ± 0.09 | 1.18 ± 0.04 | (Cr, Mo) | |

| IT55 | e1 | 50.34 ± 1.88 | 3.24 ± 0.09 | 1.59 ± 0.07 | 1.04 ± 0.01 | 1.05 ± 0.02 | 40.21 ± 1.84 | 1.08 ± 0.04 | 1.45 ± 0.03 | TiNi |

| e2 | 31.81 ± 1.89 | 2.54 ± 0.05 | 2.02 ± 0.06 | 1.13 ± 0.03 | 1.14 ± 0.02 | 55.53 ± 2.02 | 3.59 ± 0.08 | 2.24 ± 0.09 | Ti2Ni | |

| e3 | 10.24 ± 0.51 | 58.43 ± 1.91 | 20.34 ± 1.01 | 3.29 ± 0.09 | 3.21 ± 0.08 | 2.22 ± 0.08 | 1.11 ± 0.02 | 1.16 ± 0.02 | (Cr, Mo) | |

| IT46 | f1 | 45.02 ± 2.31 | 4.63 ± 0.24 | 2.50 ± 0.06 | 3.25 ± 0.07 | 2.51 ± 0.07 | 38.35 ± 1.93 | 2.18 ± 0.04 | 1.56 ± 0.02 | TiNi |

| f2 | 54.54 ± 2.01 | 6.94 ± 0.07 | 5.62 ± 0.06 | 2.62 ± 0.03 | 1.50 ± 0.05 | 22.08 ± 0.99 | 4.33 ± 0.02 | 2.37 ± 0.04 | TiNi3 | |

| f3 | 10.59 ± 0.19 | 60.23 ± 1.88 | 18.84 ± 0.97 | 3.57 ± 0.06 | 3.21 ± 0.06 | 1.04 ± 0.03 | 1.32 ± 0.02 | 1.20 ± 0.03 | (Cr, Mo) | |

| IT37 | g1 | 41.59 ± 1.01 | 5.56 ± 0.08 | 3.21 ± 0.03 | 1.77 ± 0.05 | 1.94 ± 0.06 | 41.24 ± 0.87 | 3.21 ± 0.04 | 1.48 ± 0.02 | TiNi |

| g2 | 58.24 ± 1.69 | 3.33 ± 0.03 | 3.21 ± 0.02 | 2.77 ± 0.06 | 1.79 ± 0.02 | 23.24 ± 0.99 | 4.55 ± 0.12 | 2.87 ± 0.08 | TiNi3 | |

| g3 | 13.34 ± 0.78 | 55.55 ± 2.43 | 17.24 ± 0.99 | 6.64 ± 0.16 | 2.89 ± 0.32 | 1.33 ± 0.04 | 1.34 ± 0.04 | 1.67 ± 0.05 | (Cr, Mo) | |

| IT28 | h1 | 35.43 ± 0.53 | 6.64 ± 0.16 | 2.97 ± 0.09 | 1.94 ± 0.09 | 1.58 ± 0.08 | 42.99 ± 1.08 | 3.54 ± 0.15 | 4.91 ± 0.18 | TiNi |

| h2 | 60.33 ± 2.63 | 5.59 ± 0.11 | 1.67 ± 0.08 | 1.04 ± 0.04 | 1.99 ± 0.03 | 21.53 ± 0.89 | 5.64 ± 0.16 | 2.21 ± 0.06 | TiNi3 | |

| h3 | 10.94 ± 0.25 | 59.64 ± 2.08 | 17.31 ± 0.76 | 5.54 ± 0.26 | 1.88 ± 0.06 | 1.69 ± 0.06 | 1.37 ± 0.05 | 1.63 ± 0.06 | (Cr, Mo) | |

| IT19 | i1 | 36.99 ± 1.36 | 7.32 ± 0.15 | 3.84 ± 0.11 | 2.59 ± 0.14 | 1.55 ± 0.07 | 44.68 ± 1.39 | 1.55 ± 0.05 | 1.48 ± 0.04 | TiNi |

| i2 | 58.34 ± 1.78 | 6.03 ± 0.14 | 2.55 ± 0.02 | 1.87 ± 0.02 | 1.43 ± 0.03 | 22.95 ± 0.77 | 3.24 ± 0.04 | 3.59 ± 0.09 | TiNi3 | |

| i3 | 9.94 ± 0.26 | 60.33 ± 2.33 | 17.84 ± 0.87 | 5.44 ± 0.15 | 1.21 ± 0.04 | 2.04 ± 0.06 | 1.33 ± 0.07 | 1.87 ± 0.09 | (Cr, Mo) | |

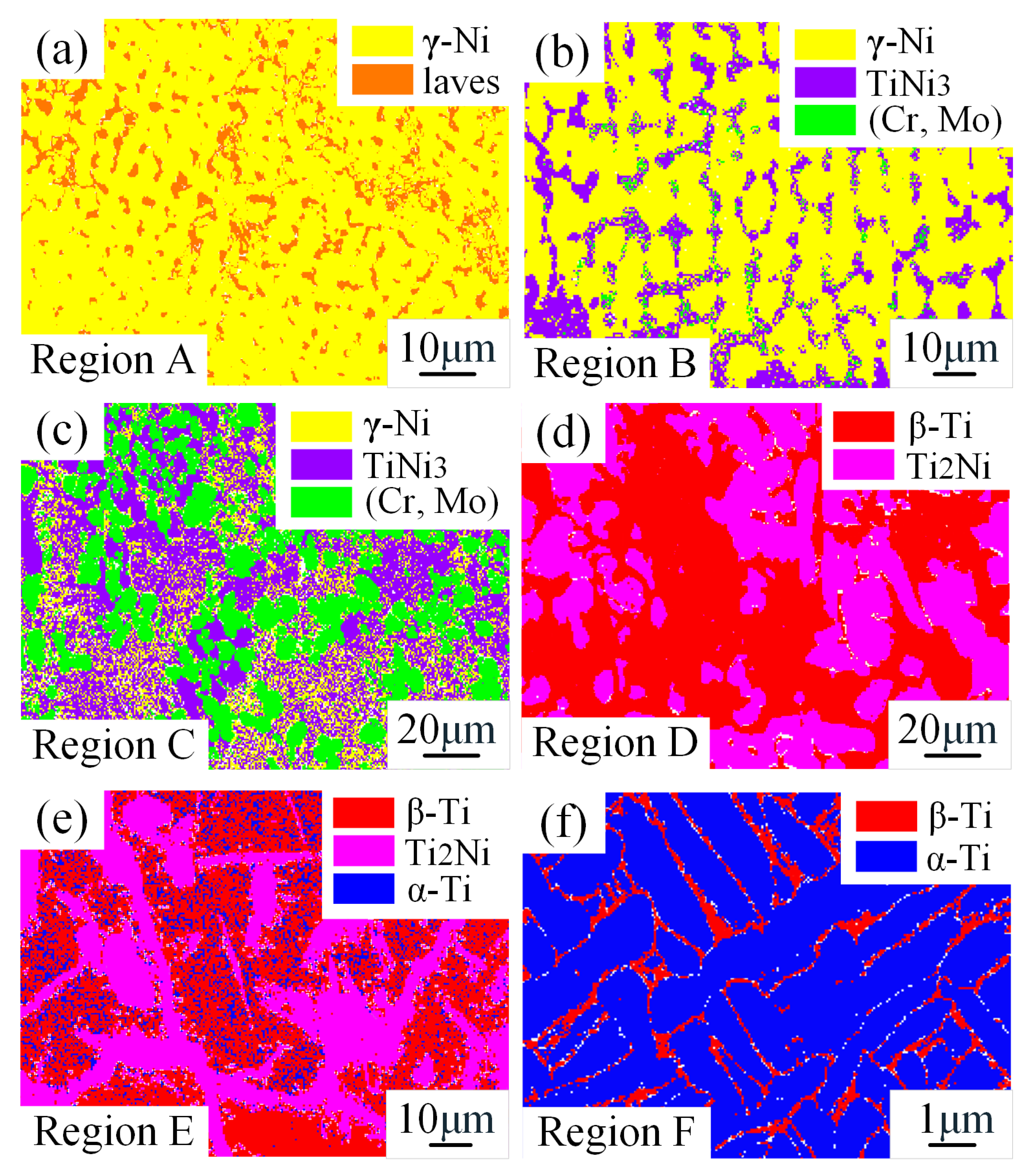

| Location | Ni | Cr | Mo | Nb | Fe | Ti | Al | V | Deduced Phases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region A | a1 | 66.57 ± 2.23 | 18.09 ± 1.01 | 2.89 ± 0.09 | 1.17 ± 0.02 | 3.75 ± 0.15 | 4.53 ± 0.13 | 1.68 ± 0.06 | 1.32 ± 0.03 | γ-Ni |

| a2 | 39.87 ± 1.03 | 17.24 ± 0.87 | 14.55 ± 0.19 | 12.97 ± 0.16 | 5.77 ± 0.15 | 7.32 ± 0.16 | 1.03 ± 0.06 | 1.25 ± 0.05 | laves | |

| Region B | b1 | 59.52 ± 2.34 | 23.06 ± 1.01 | 4.87 ± 0.09 | 2.68 ± 0.04 | 4.53 ± 0.09 | 2.60 ± 0.05 | 1.28 ± 0.04 | 1.46 ± 0.03 | γ-Ni |

| b2 | 57.78 ± 2.01 | 22.43 ± 1.03 | 6.06 ± 0.05 | 2.64 ± 0.04 | 3.11 ± 0.11 | 3.31 ± 0.09 | 2.03 ± 0.07 | 2.64 ± 0.08 | γ-Ni | |

| b3 | 60.89 ± 2.66 | 6.78 ± 0.16 | 3.32 ± 0.07 | 4.21 ± 0.10 | 1.03 ± 0.04 | 20.19 ± 0.66 | 2.22 ± 0.07 | 1.36 ± 0.05 | TiNi3 | |

| b4 | 14.40 ± 0.88 | 54.52 ± 1.96 | 23.15 ± 1.03 | 1.11 ± 0.02 | 1.10 ± 0.03 | 2.48 ± 0.03 | 1.52 ± 0.02 | 1.72 ± 0.05 | (Cr, Mo) | |

| Region C | c1 | 57.77 ± 1.69 | 13.66 ± 0.89 | 6.96 ± 0.36 | 2.71 ± 0.03 | 3.35 ± 0.06 | 12.64 ± 0.55 | 1.04 ± 0.05 | 1.87 ± 0.06 | γ-Ni + TiNi3 |

| c2 | 3.11 ± 0.04 | 64.22 ± 2.34 | 24.83 ± 1.56 | 1.03 ± 0.02 | 2.29 ± 0.07 | 2.11 ± 0.03 | 1.13 ± 0.03 | 1.28 ± 0.06 | (Cr, Mo) | |

| Region D | d1 | 11.19 ± 0.66 | 6.28 ± 0.15 | 1.82 ± 0.04 | 1.60 ± 0.03 | 1.87 ± 0.09 | 68.82 ± 2.65 | 3.53 ± 0.08 | 4.89 ± 0.09 | β-Ti |

| d2 | 27.53 ± 1.56 | 1.32 ± 0.05 | 1.14 ± 0.04 | 1.04 ± 0.02 | 1.80 ± 0.05 | 60.49 ± 2.34 | 3.32 ± 0.06 | 3.36 ± 0.08 | Ti2Ni | |

| d3 | 27.70 ± 1.33 | 2.83 ± 0.09 | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 1.19 ± 0.05 | 1.35 ± 0.04 | 62.73 ± 2.08 | 1.90 ± 0.06 | 1.01 ± 0.05 | Ti2Ni | |

| Region E | e1 | 1.56 ± 0.05 | 3.43 ± 0.09 | 1.63 ± 0.05 | 1.15 ± 0.05 | 1.40 ± 0.04 | 78.30 ± 3.01 | 9.39 ± 0.89 | 3.14 ± 0.04 | α-Ti |

| e2 | 5.08 ± 0.15 | 4.11 ± 0.11 | 1.64 ± 0.05 | 1.29 ± 0.04 | 1.45 ± 0.04 | 73.98 ± 3.21 | 5.94 ± 0.43 | 6.51 ± 0.28 | β-Ti | |

| e3 | 5.37 ± 0.11 | 3.51 ± 0.09 | 1.72 ± 0.06 | 1.22 ± 0.03 | 1.56 ± 0.03 | 75.71 ± 2.99 | 4.41 ± 0.13 | 6.50 ± 0.38 | β-Ti | |

| e4 | 29.45 ± 1.03 | 1.91 ± 0.09 | 1.33 ± 0.08 | 1.13 ± 0.07 | 1.06 ± 0.08 | 57.19 ± 1.87 | 6.36 ± 0.06 | 1.57 ± 0.04 | Ti2Ni | |

| e5 | 28.51 ± 1.01 | 1.00 ± 0.03 | 1.05 ± 0.04 | 1.11 ± 0.06 | 1.42 ± 0.05 | 63.92 ± 1.88 | 1.47 ± 0.05 | 1.52 ± 0.03 | Ti2Ni | |

| e6 | 26.90 ± 1.23 | 1.80 ± 0.10 | 1.12 ± 0.09 | 1.02 ± 0.03 | 1.28 ± 0.02 | 64.41 ± 2.13 | 1.92 ± 0.04 | 1.55 ± 0.05 | Ti2Ni | |

| Region F | f1 | - | - | - | - | - | 88.99 ± 2.44 | 8.76 ± 0.26 | 2.25 ± 0.04 | α-Ti |

| f2 | - | - | - | - | - | 86.73 ± 2.29 | 3.60 ± 0.05 | 9.67 ± 0.18 | β-Ti | |

| Region | Phase Type and Volume Fraction (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ-Ni | laves | (Cr, Mo) | TiNi3 | Ti2Ni | β-Ti | α-Ti | |

| Region A | 81.4 | 17.1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Region B | 73.2 | - | 3.0 | 23.0 | - | - | - |

| Region C | 19.2 | - | 38.4 | 38.1 | - | - | - |

| Region D | - | - | - | - | 39.4 | 57.7 | |

| Region E | - | - | - | - | 35.1 | 51.3 | 9.3 |

| Region F | - | - | - | - | - | 8.7 | 90.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, W.; Xu, G.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cui, G.; Qin, P.; Shang, J.; Fan, X. Laser Directed Energy Deposition of Inconel625 to Ti6Al4V Heterostructure via Nonlinear Gradient Transition Interlayers. Materials 2025, 18, 5598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245598

Wang W, Xu G, Hou Y, Zhang C, Cui G, Qin P, Shang J, Fan X. Laser Directed Energy Deposition of Inconel625 to Ti6Al4V Heterostructure via Nonlinear Gradient Transition Interlayers. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245598

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Wenbo, Guojian Xu, Yaqing Hou, Chenyi Zhang, Guohao Cui, Pengyu Qin, Juncheng Shang, and Xiuru Fan. 2025. "Laser Directed Energy Deposition of Inconel625 to Ti6Al4V Heterostructure via Nonlinear Gradient Transition Interlayers" Materials 18, no. 24: 5598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245598

APA StyleWang, W., Xu, G., Hou, Y., Zhang, C., Cui, G., Qin, P., Shang, J., & Fan, X. (2025). Laser Directed Energy Deposition of Inconel625 to Ti6Al4V Heterostructure via Nonlinear Gradient Transition Interlayers. Materials, 18(24), 5598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245598