Flexural Performance of CLT Plates Under Coupling Effect of Load and Moisture Content

Abstract

1. Introduction

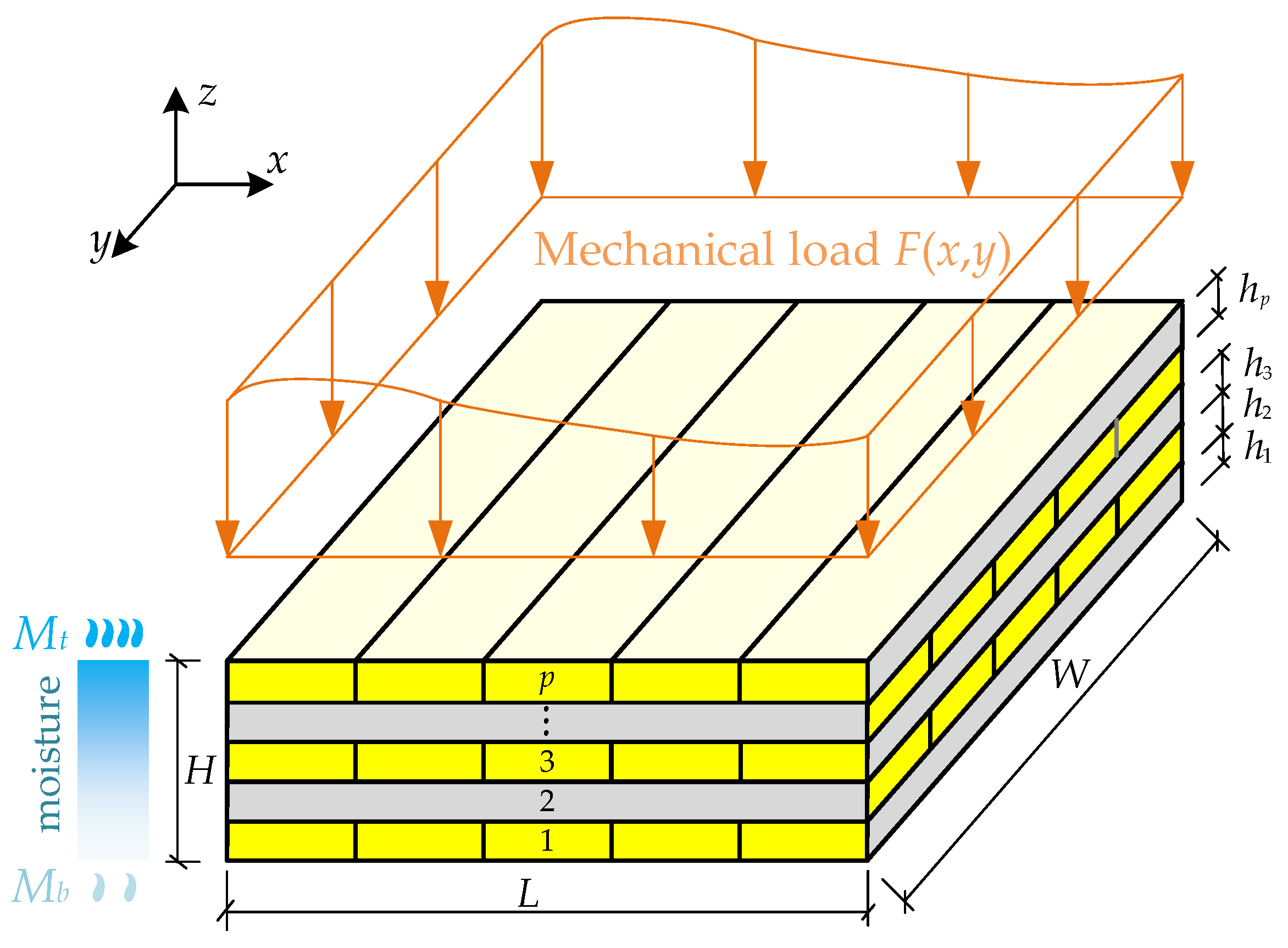

2. Analytical Model for CLT Plates

2.1. Governing Equations

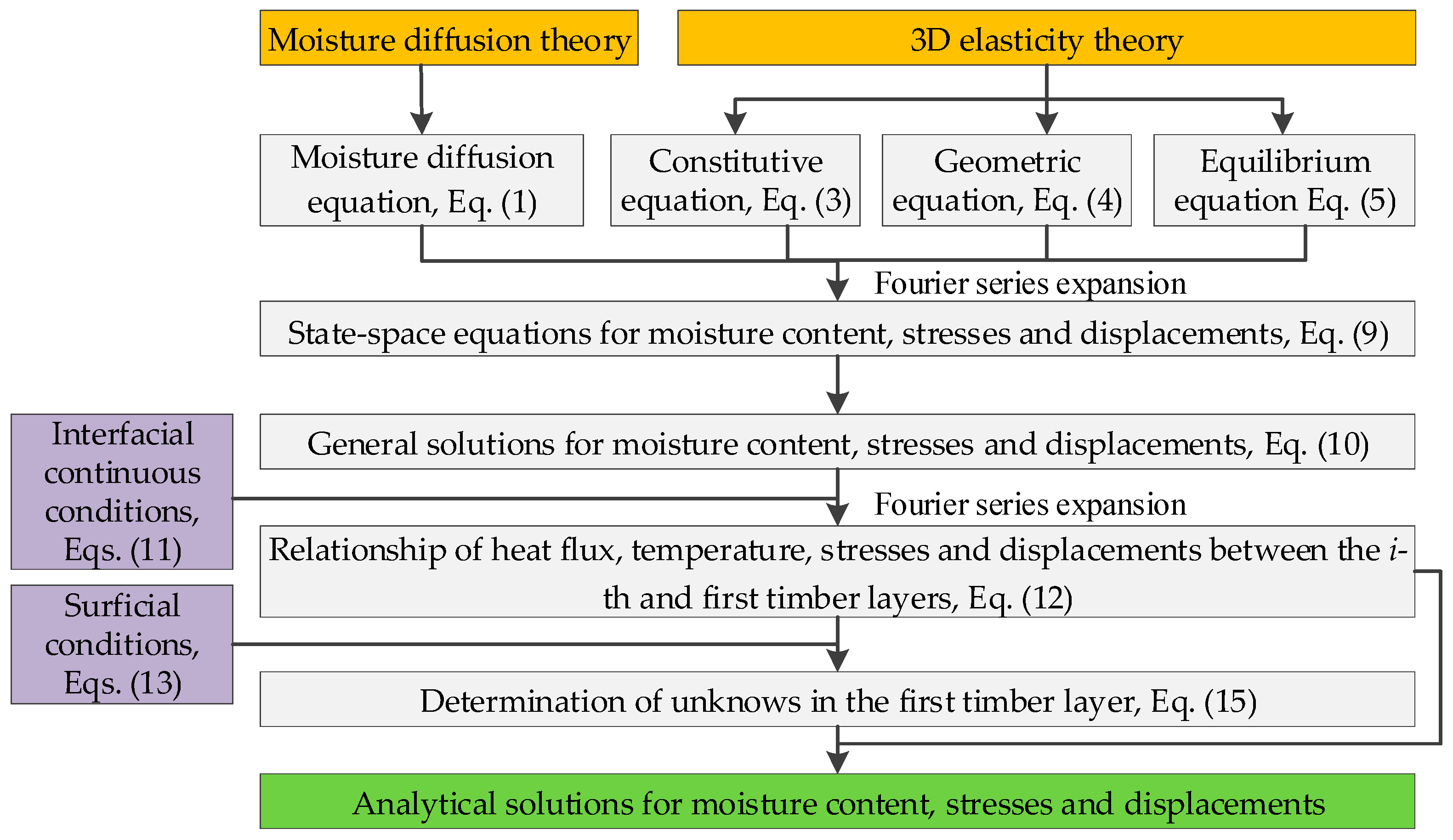

2.2. Solutions of Moisture, Stresses and Displacements of CLT Plate

3. Numerical Model

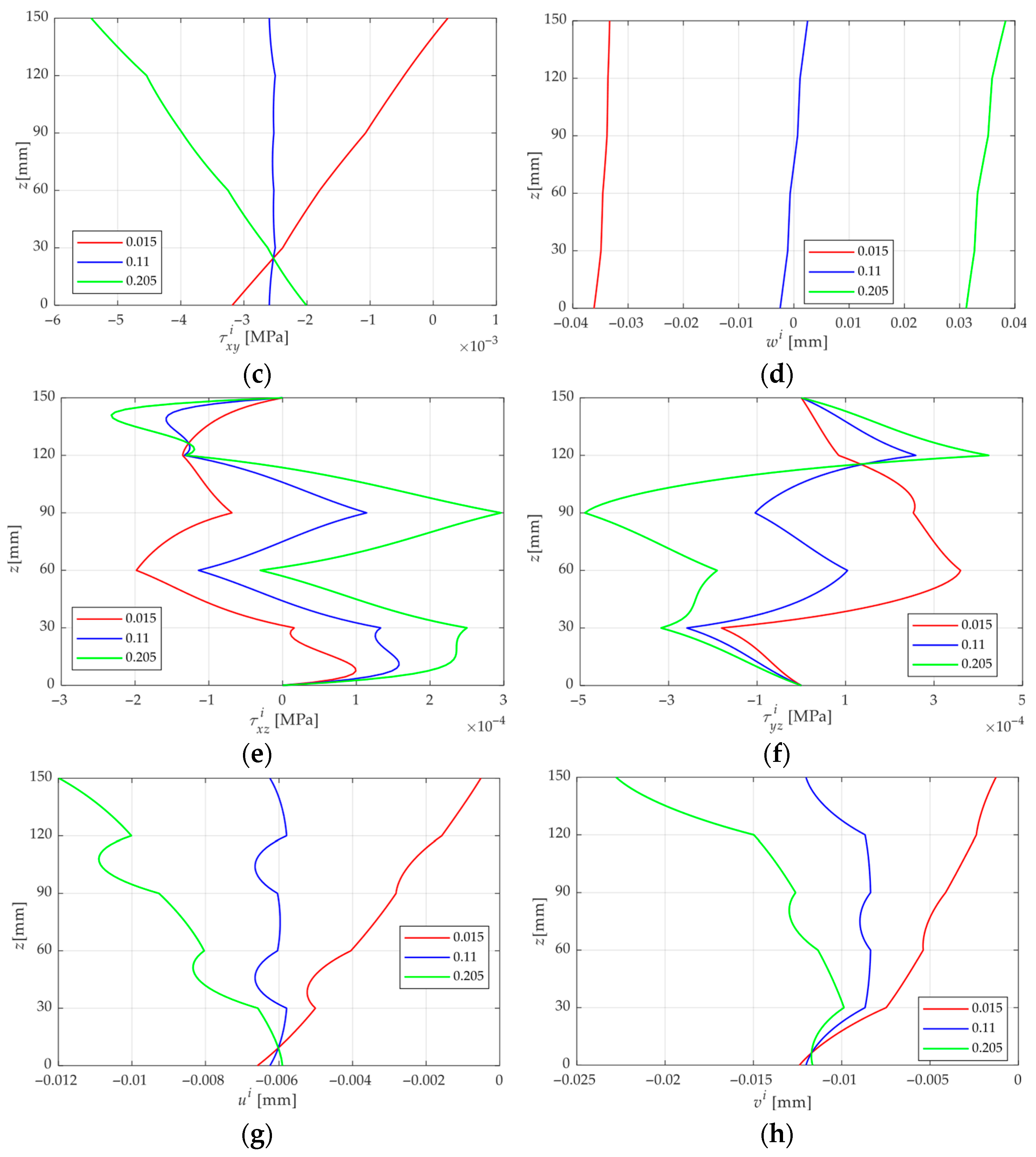

4. Results and Discussion

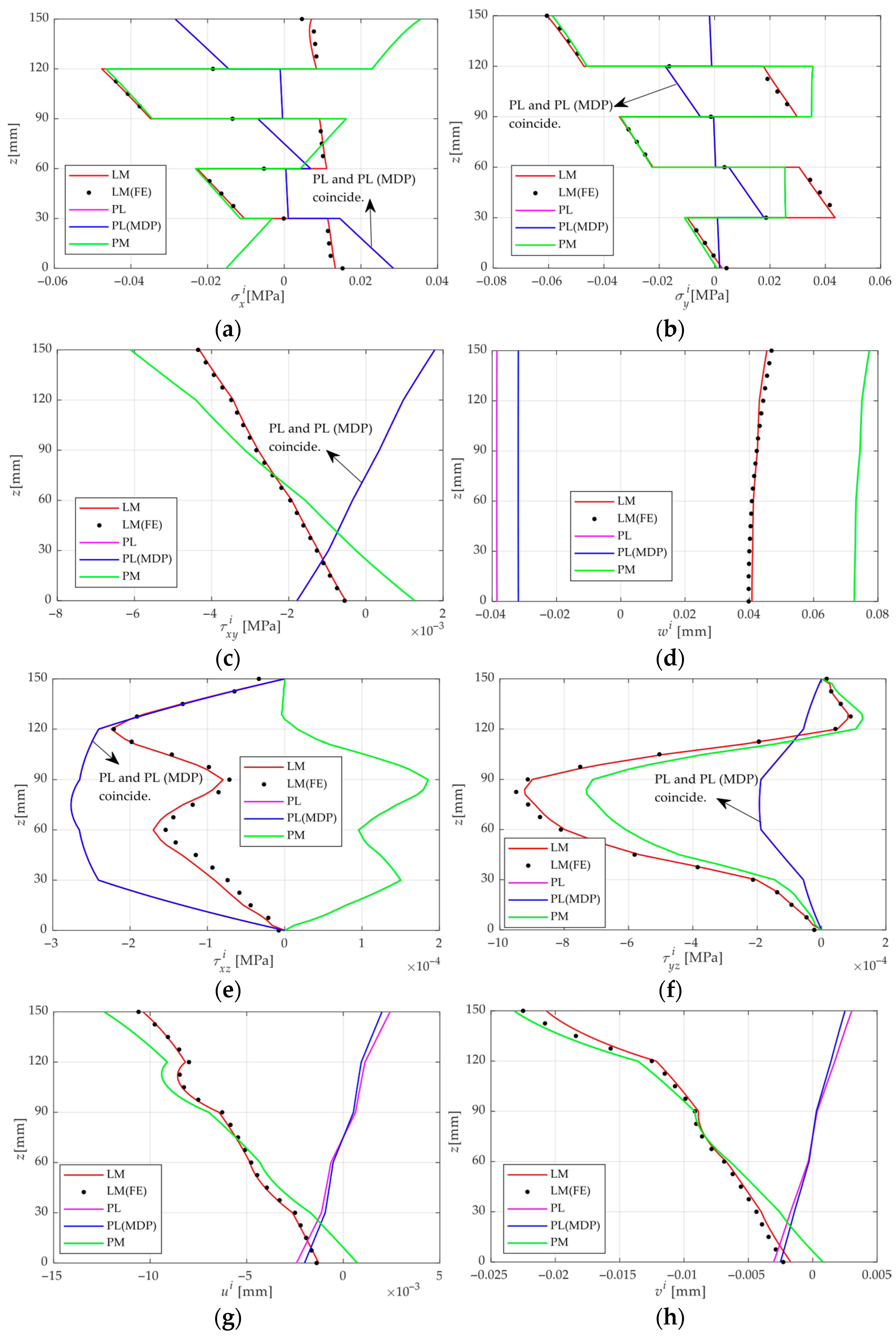

4.1. Comparison and Decoupling Analyses

4.2. Effect of Wood Specie

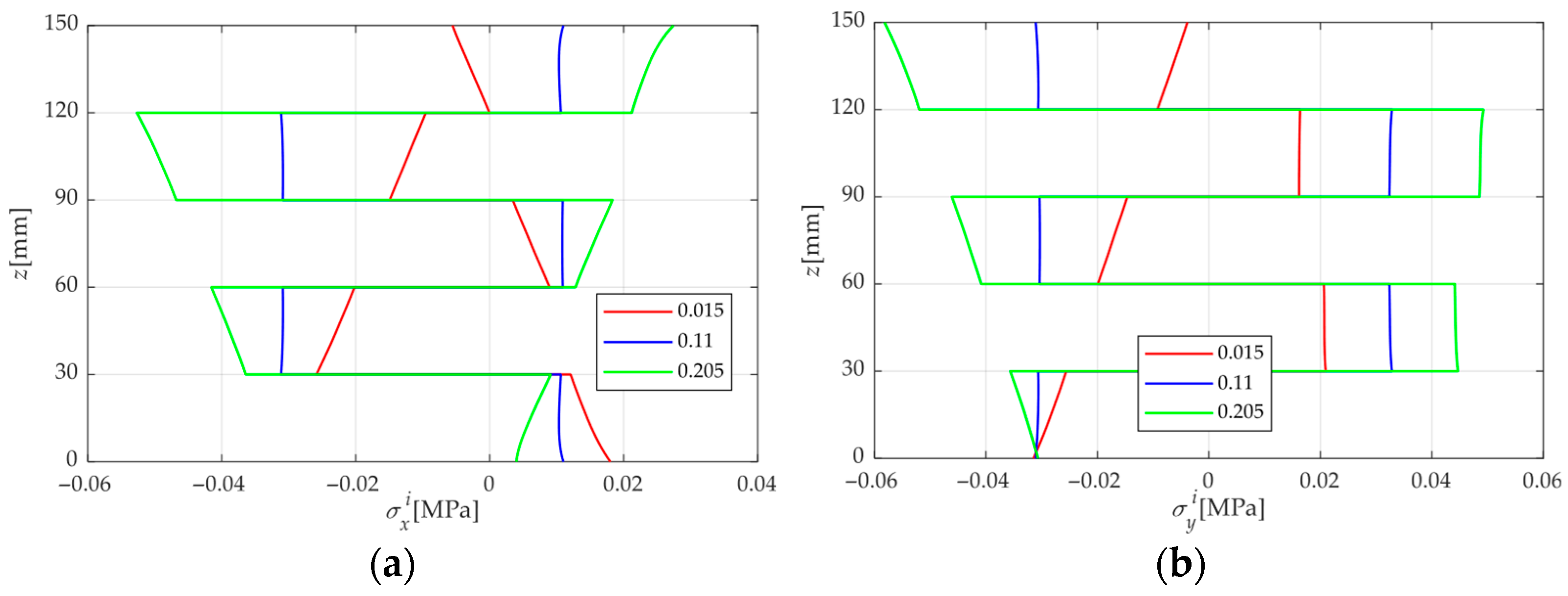

4.3. Effect of Surface MC Difference

5. Conclusions

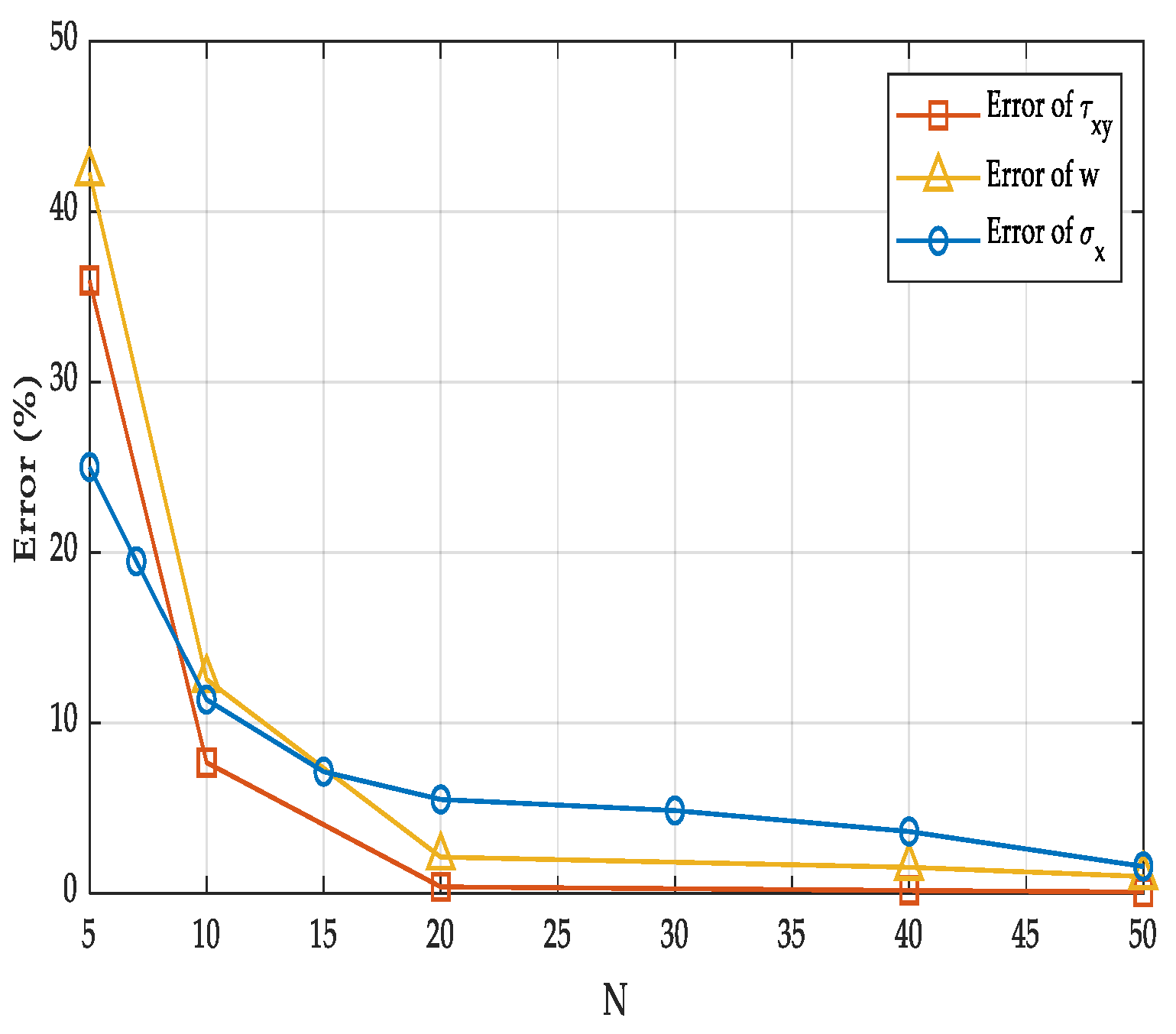

- The FE results tend to agree with the present analytical solution as the FE mesh becomes finer. When the number of finite element elements reaches 6.25 × 109, the errors in the typical normal stress, shear stress, and deflection compared with the present solution are 1.59%, 0.0901%, and 1.02%, respectively. In addition, the FE results exhibit relatively large discrepancies near the surfaces. The analytical solution provides significantly higher computational efficiency in predicting the LM-coupled response of CLT plates than the FE simulations, as the latter require increasingly longer computation times when the mesh is refined.

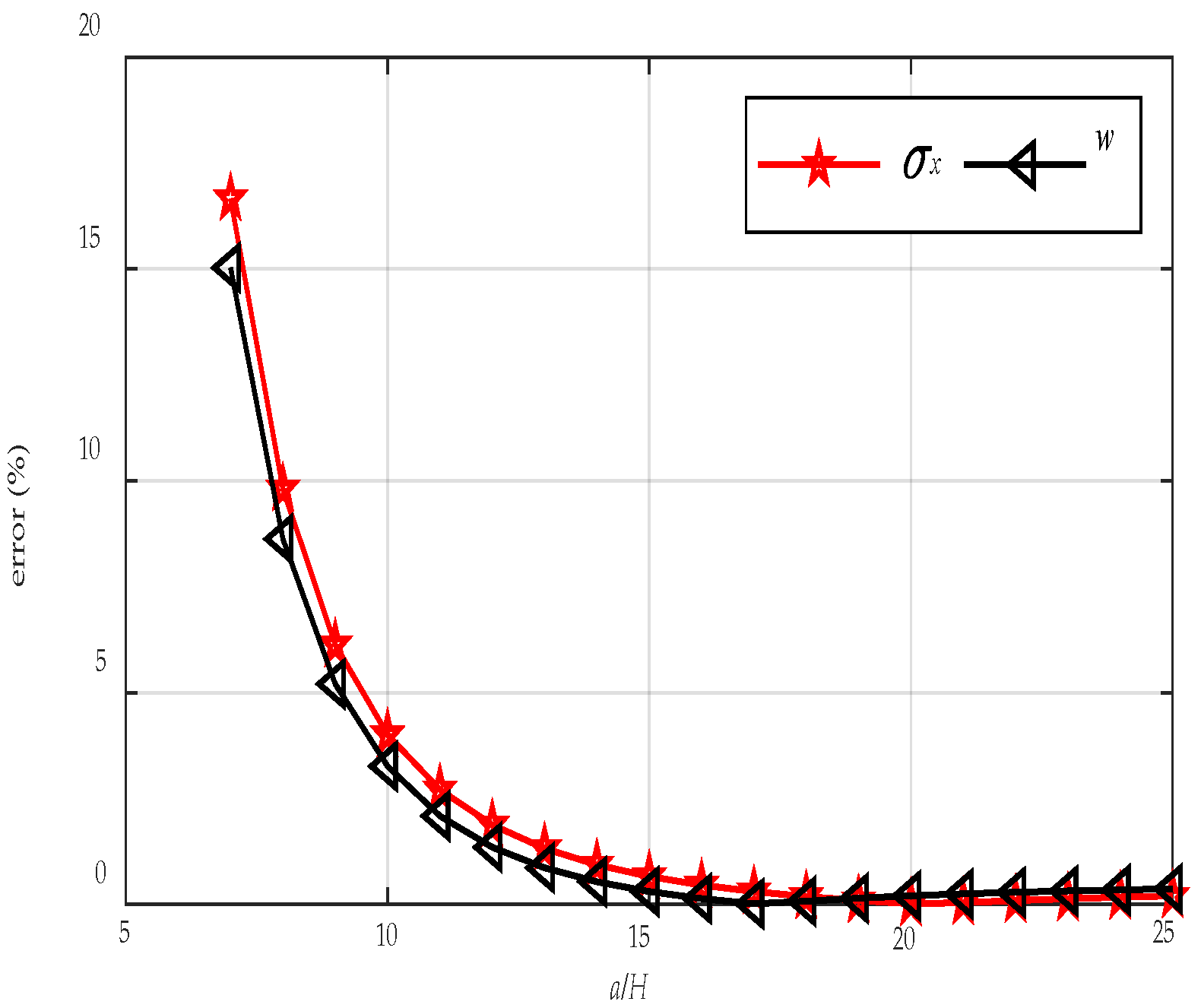

- The Kirchhoff plate solution agrees well with the present solution when the length-to-thickness ratio of the CLT plate is large; however, the discrepancy increases markedly as the plate becomes thicker. When a/H = 7, the errors of normal stress, and deflection reach 16.66% and 15.03%. This is due to the transverse shear deformation of the plate being neglected in the Kirchhoff theory.

- For the mechanical analysis of CLT plates under LM conditions, it is found that the conventional superposition principle is no longer applicable, leading to errors of up to 18.2%. This study proposes a modified superposition principle that accounts for the effect of MDP under PL conditions in addition to the traditional superposition approach.

- When the MC at the top surface of the CLT plate exceeds that at the bottom, stress and displacement generally occur in opposing directions. This is because the external load tends to bend the plate downward, whereas the moisture-induced expansion on the upper surface drives an upward deformation. Consequently, under LM coupling, these opposing flexural effects partially compensate for each other, thus reducing the overall stress and deformation of the CLT plate.

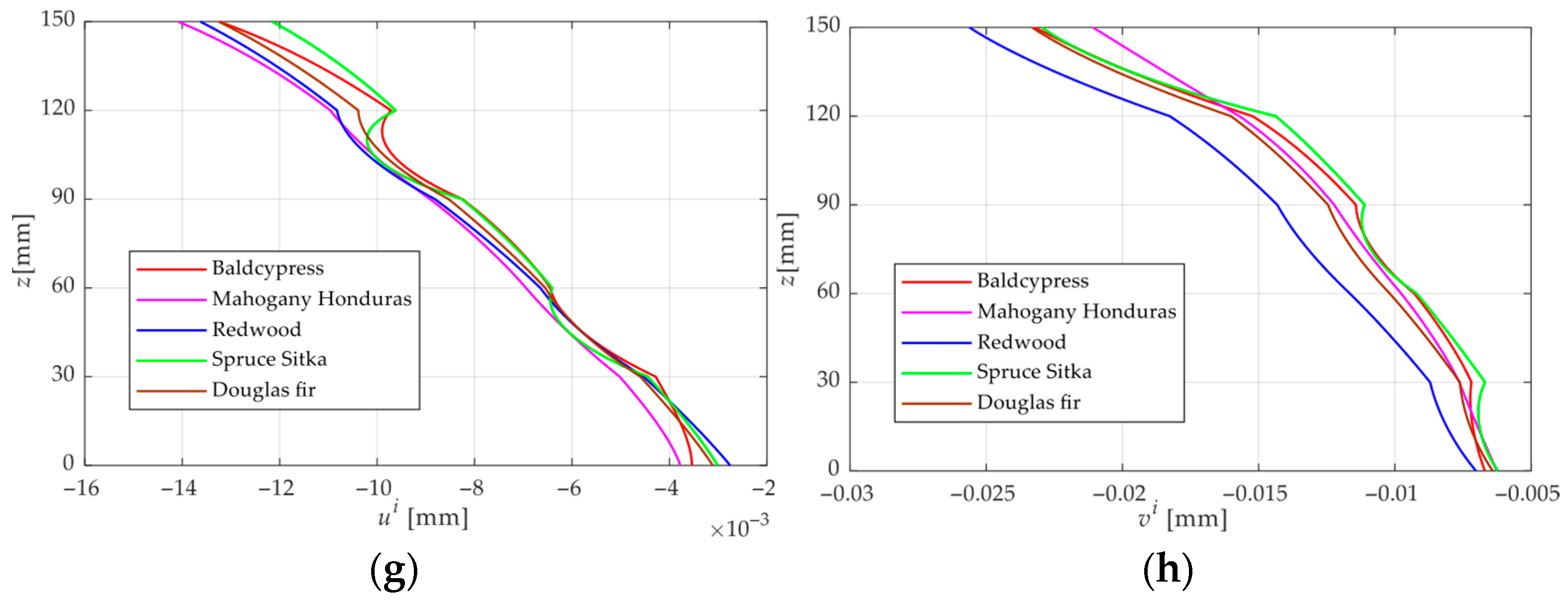

- For a CLT plate under PL conditions, the stresses and displacements exhibit clear symmetric or antisymmetric distributions with respect to the mid-plane of the plate. However, such symmetry occurs only when the CLT is under uniform moisture content, and in this case, the symmetry is exactly opposite to that observed under PL conditions.

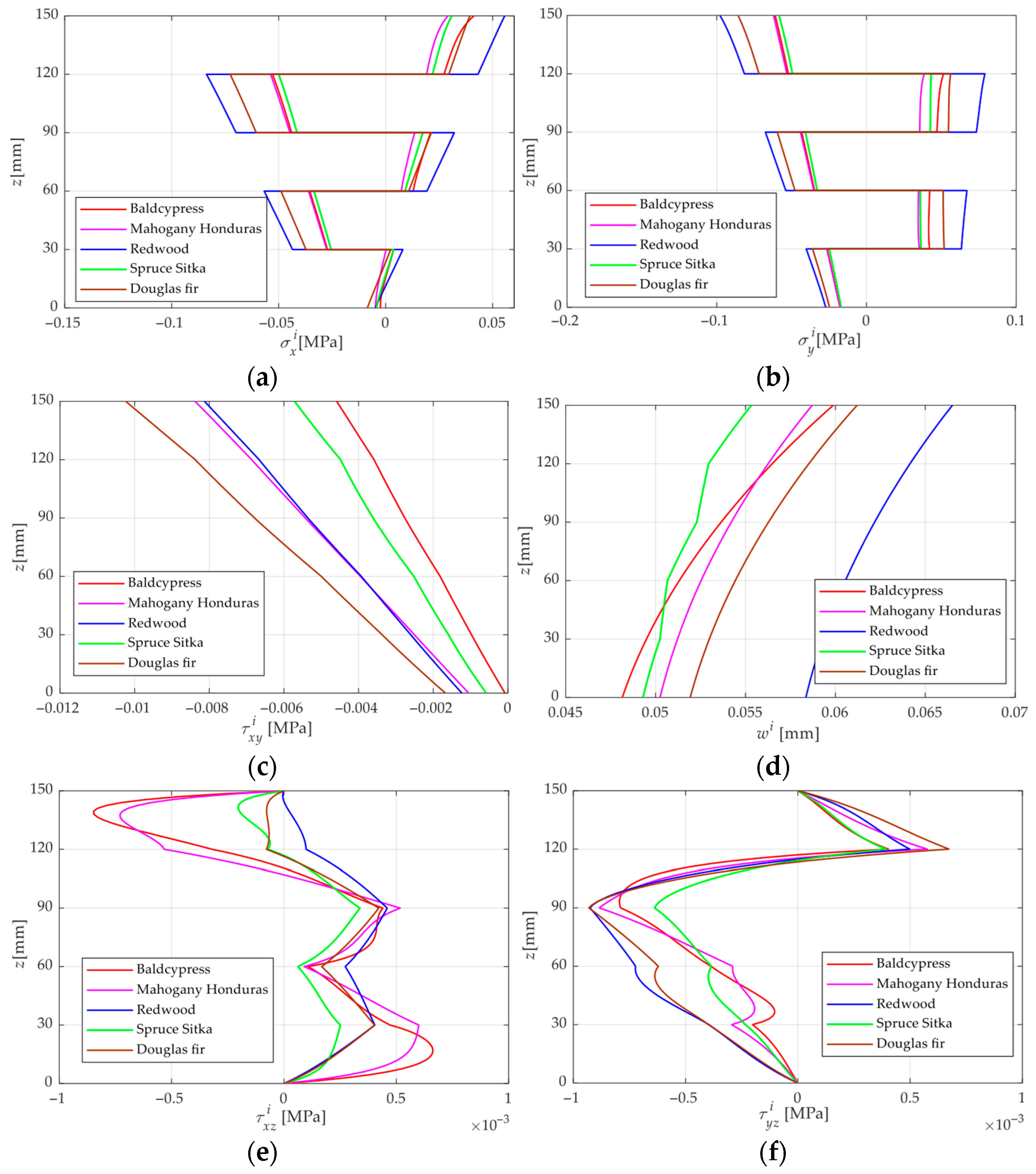

- Through the analysis of mechanical behaviors of different wood species under the PM condition, it can be concluded that the primary factors governing the moisture-induced stress and displacement responses are the elastic modulus, shear modulus, and the relative magnitude of the moisture expansion coefficient. Owing to the pronounced elastic modulus anisotropy between the longitudinal and tangential directions, moisture-induced stresses differ markedly between odd and even laminae, with adjacent layers generally exhibiting opposite stress directions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

Appendix A

References

- Pang, S.-J.; Jeong, G.Y. Swelling and shrinkage behaviors of cross-laminated timber made of different species with various lamina thickness and combinations. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 240, 117924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ido, H.; Nagao, H.; Kato, H.; Miura, S. Strength properties and effect of moisture content on the bending and compressive strength parallel to the grain of sugi (Cryptomeria japonica) round timber. J. Wood Sci. 2013, 59, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Sun, X.; Li, Z.; Feng, W. Bending, shear, and compressive properties of three- and five-layer cross-laminated timber fabricated with black spruce. J. Wood Sci. 2020, 66, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, M.; Hiramatsu, Y.; Shindo, K.; Ohki, F.; Miyatake, A. Bending performance of sugi cross-laminated timber (CLT) composed of different thickness laminae. J. Wood Sci. 2025, 71, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, A.; Schirén, W.; Hu, M. Dynamic and quasi-static evaluation of stiffness properties of CLT: Longitudinal MoE and effective rolling shear modulus. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2025, 83, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaher Omer Ahmed, A.; Garab, J.; Horváth-Szováti, E.; Kozelka, J.; Bejó, L. The Bending Properties of Hybrid Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) Using Various Species Combinations. Materials 2023, 16, 7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaai, Y.; Takanashi, R.; Ishihara, W.; Ohashi, Y.; Sawata, K.; Sasaki, T. Out-of-plane shear strength of cross-laminated timber made of Japanese Larch (Larix kaempferi) with various layups and spans. J. Wood Sci. 2023, 69, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülzow, A.; Richter, K.; Steiger, R. Influence of wood moisture content on bending and shear stiffness of cross laminated timber panels. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2011, 69, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Creep behavior of wood under cyclic moisture changes: Interaction between load effect and moisture effect. J. Wood Sci. 2016, 62, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, Z.; Li, H.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Z. Study on in-plane shear failure mode of cross-laminated timber panel. J. Wood Sci. 2022, 68, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, K.; Mori, T.; Mestar, M.; Inoue, R. Evaluation of in-plane shear performance of CLT using the asymmetric four-point bending test method and detailed examination of the method. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2025, 83, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzinski, S.; Crovella, P.L. Investigating the Out-of-Plane Bending Stiffness Properties in Hybrid Species Diagonal-Cross-Laminated Timber Panels. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takanashi, R.; Ohashi, Y.; Ishihara, W.; Matsumoto, K. Long-term bending properties of cross-laminated timber made from Japanese larch under constant environment. J. Wood Sci. 2021, 67, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Evaluating rolling shear strength properties of cross-laminated timber by short-span bending tests and modified planar shear tests. J. Wood Sci. 2017, 63, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobeš, P.; Lokaj, A.; Vavrušová, K. Stiffness and Deformation Analysis of Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) Panels Made of Nordic Spruce Based on Experimental Testing, Analytical Calculation and Numerical Modeling. Buildings 2023, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lee, H.; Choi, G.; Kang, S. Mechanical properties of ply-lam cross-laminated timbers fabricated with lumber and plywood. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2024, 82, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Yusof, N.; Tahir, P.M.; Lee, S.H.; Khan, M.A.; Mohammad Suffian James, R. Mechanical and physical properties of Cross-Laminated Timber made from Acacia mangium wood as function of adhesive types. J. Wood Sci. 2019, 65, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Branco, J.M.; Mehdipour, Z.; Xavier, J.; Rebouças, A.S.; Lourenço, P.B. Strain variation analysis of cross-laminated timber elements under cyclic moisture. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 41, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloisio, A.; Pasca, D.P.; Tomasi, R.; Fragiacomo, M. Sensitivity of bending stiffness to moisture content in adhesive-free wooden-doweled cross-laminated timber panels. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 490, 142143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandstätter, F.; Kalbe, K.; Autengruber, M.; Lukacevic, M.; Kalamees, T.; Ruus, A.; Annuk, A.; Füssl, J. Numerical simulation of CLT moisture uptake and dry-out following water infiltration through end-grain surfaces. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.; Riggio, M. Monitoring Moisture Performance of Cross-Laminated Timber Building Elements during Construction. Buildings 2019, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.-L.; Guan, H.-Y.; Kei, S. Effects of Moisture Content and Grain Direction on the Elastic Properties of Beech Wood Based on Experiment and Finite Element Method. Forests 2021, 12, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florisson, S.; Vessby, J.; Ormarsson, S. A three-dimensional numerical analysis of moisture flow in wood and of the wood’s hygro-mechanical and visco-elastic behaviour. Wood Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 1269–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yao, L.; Ma, Y.; Hou, Z.; Tang, J.; Wang, Y.; Ni, Y. The Moisture Diffusion Equation for Moisture Absorption of Multiphase Symmetrical Sandwich Structures. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Park, J.-H.; Chang, Y.-S.; Eom, C.-D.; Lee, J.-J.; Yeo, H. Classification of the conductance of moisture through wood cell components. J. Wood Sci. 2013, 59, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokovyy, Y.V.; Ma, C.C. Three-Dimensional Elastic Analysis of Transversely-Isotropic Composites. J. Mech. 2017, 33, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory. Wood Handbook: Wood as an Engineering Material; General Technical Report FPL–GTR–282; Forest Products Laboratory: Madison, WI, USA, 2021.

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, D.; Huo, R.; Xu, X. Elasticity solution of laminated beams with temperature-dependent material properties under a combination of uniform thermo-load and mechanical loads. J. Cent. South Univ. 2018, 25, 2537–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foraboschi, P. Three-layered plate: Elasticity solution. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 60, 764–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wu, Y.-F. Two-dimensional analytical solutions of simply supported composite beams with interlayer slips. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2007, 44, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material Property | Bald Cypress | Mahogany Honduras | Redwood | Spruce Sitka | Douglas Fir |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL (12%) | 10,890 | 11,330 | 10,120 | 11,880 | 13,297.7 |

| EL (green) | 8910 | 10,120 | 8910 | 9350 | 10,717.5 |

| ET/EL | 0.039 | 0.064 | 0.089 | 0.043 | 0.050 |

| ER/EL | 0.084 | 0.107 | 0.087 | 0.078 | 0.068 |

| GLR/EL | 0.063 | 0.066 | 0.066 | 0.064 | 0.064 |

| GLT/EL | 0.054 | 0.086 | 0.077 | 0.061 | 0.078 |

| GRT/EL | 0.007 | 0.028 | 0.011 | 0.003 | 0.007 |

| μLR | 0.338 | 0.314 | 0.36 | 0.372 | 0.292 |

| μLT | 0.326 | 0.533 | 0.346 | 0.467 | 0.449 |

| μTL | 0.013 | 0.034 | 0.031 | 0.025 | 0.029 |

| μTR | 0.356 | 0.326 | 0.4 | 0.245 | 0.374 |

| λL | 1 × 10−7 | 2.5 × 10−7 | 5 × 10−7 | 1.8 × 10−7 | 5 × 10−7 |

| λT | 6.2 × 10−2 | 4.2 × 10−2 | 4 × 10−8 | 7 × 10−8 | 5 × 10−8 |

| λR | 3.8 × 10−2 | 3 × 10−2 | 4 × 10−8 | 7 × 10−8 | 5 × 10−8 |

| βL | 2 × 10−5 | 2 × 10−5 | 1 × 10−5 | 2 × 10−5 | 2 × 10−5 |

| βT | 6.2 × 10−4 | 4.2 × 10−4 | 5 × 10−4 | 5 × 10−4 | 5.5 × 10−4 |

| βR | 3.8 × 10−4 | 3 × 10−4 | 2.4 × 10−4 | 3 × 10−4 | 2.8 × 10−4 |

| Mp | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.24 |

| Solution | Present | FE | Experiment Repeated Tests | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Average | |||

| 3-layer | 62.49 | 63.24 | 59.5 | 69.47 | 75.12 | 68.03 |

| 5-layer | 83.77 | 84.69 | 85.76 | 87.19 | 104 | 92.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Zhang, T.; Wang, H.; Zhao, A.; Wu, P. Flexural Performance of CLT Plates Under Coupling Effect of Load and Moisture Content. Materials 2025, 18, 5597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245597

Xu J, Zhang T, Wang H, Zhao A, Wu P. Flexural Performance of CLT Plates Under Coupling Effect of Load and Moisture Content. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245597

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jinpeng, Tianyi Zhang, Huanyu Wang, Aiguo Zhao, and Peng Wu. 2025. "Flexural Performance of CLT Plates Under Coupling Effect of Load and Moisture Content" Materials 18, no. 24: 5597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245597

APA StyleXu, J., Zhang, T., Wang, H., Zhao, A., & Wu, P. (2025). Flexural Performance of CLT Plates Under Coupling Effect of Load and Moisture Content. Materials, 18(24), 5597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245597