Improving the Strength of Eucalyptus Wood Joints Through Optimized Rotary Welding Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Pretreatment of Eucalyptus Wood Substrate

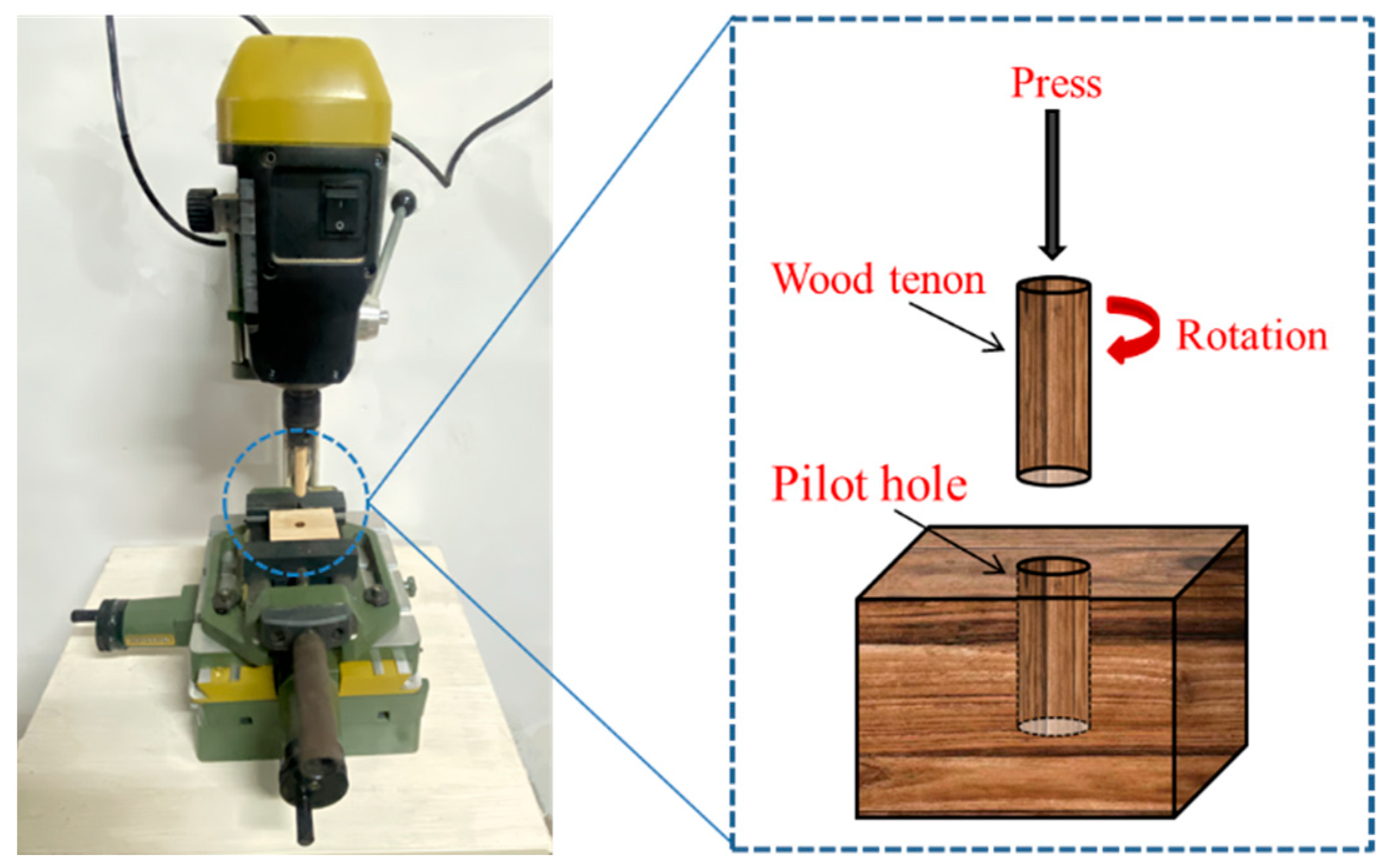

2.3. Preparation and Performance Testing of Welded Wood

2.4. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Tenon-to-Pilot Hole Diameter Ratio on the Performance of Welded Wood

3.2. Effect of Welding Dwell Time on the Performance of Welded Wood

3.3. Effect of Welding Depth on the Performance of Welded Wood

3.4. Effect of Welding Base Surface on the Performance of Welded Wood

3.5. Effect of Insertion Angle on the Performance of Welded Wood

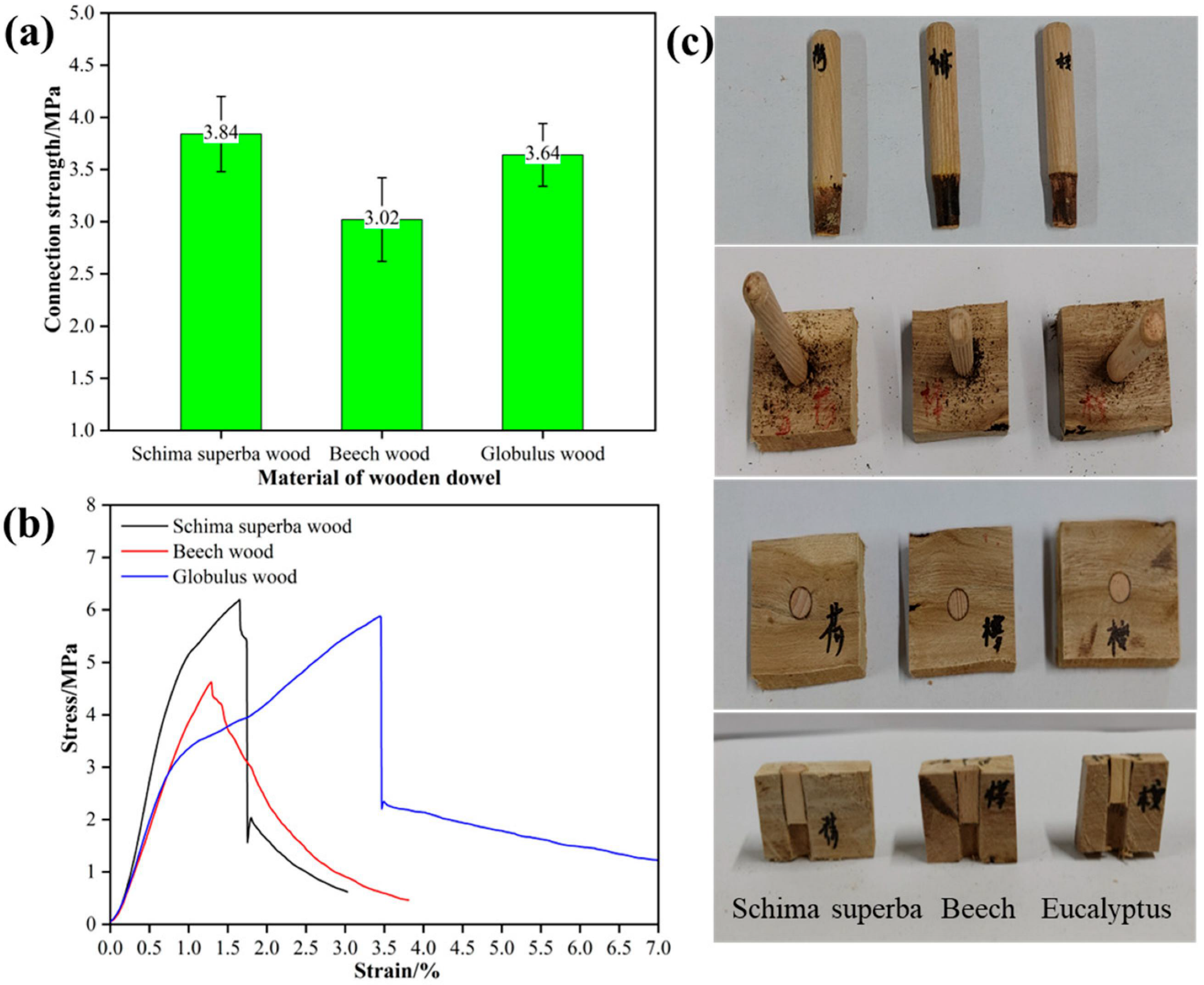

3.6. Effect of Tenon Species on the Performance of Welded Wood

3.7. FT-IR Spectroscopy Analysis

3.8. XPS Analysis

3.9. XRD Analysis

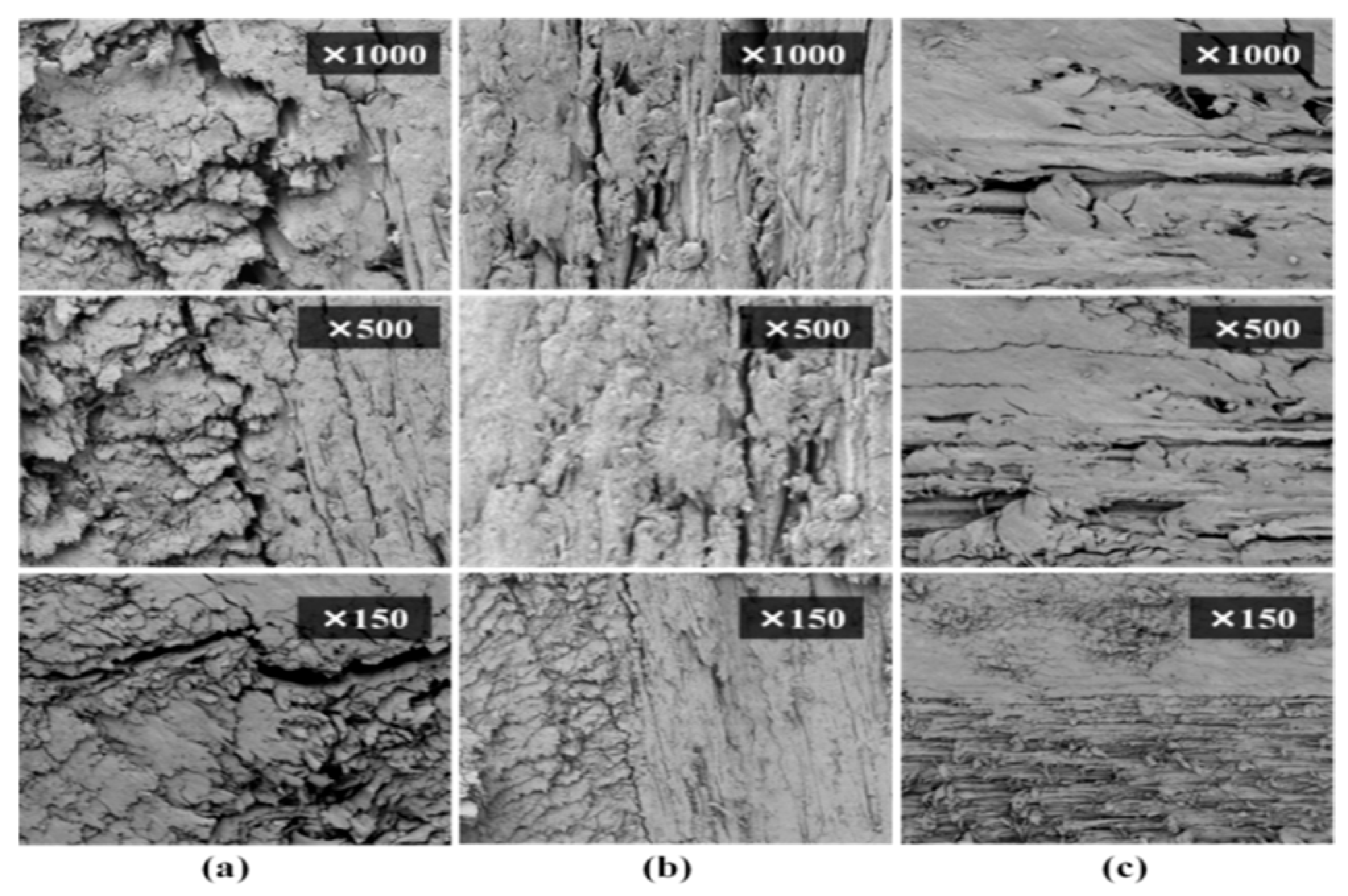

3.10. SEM Analysis

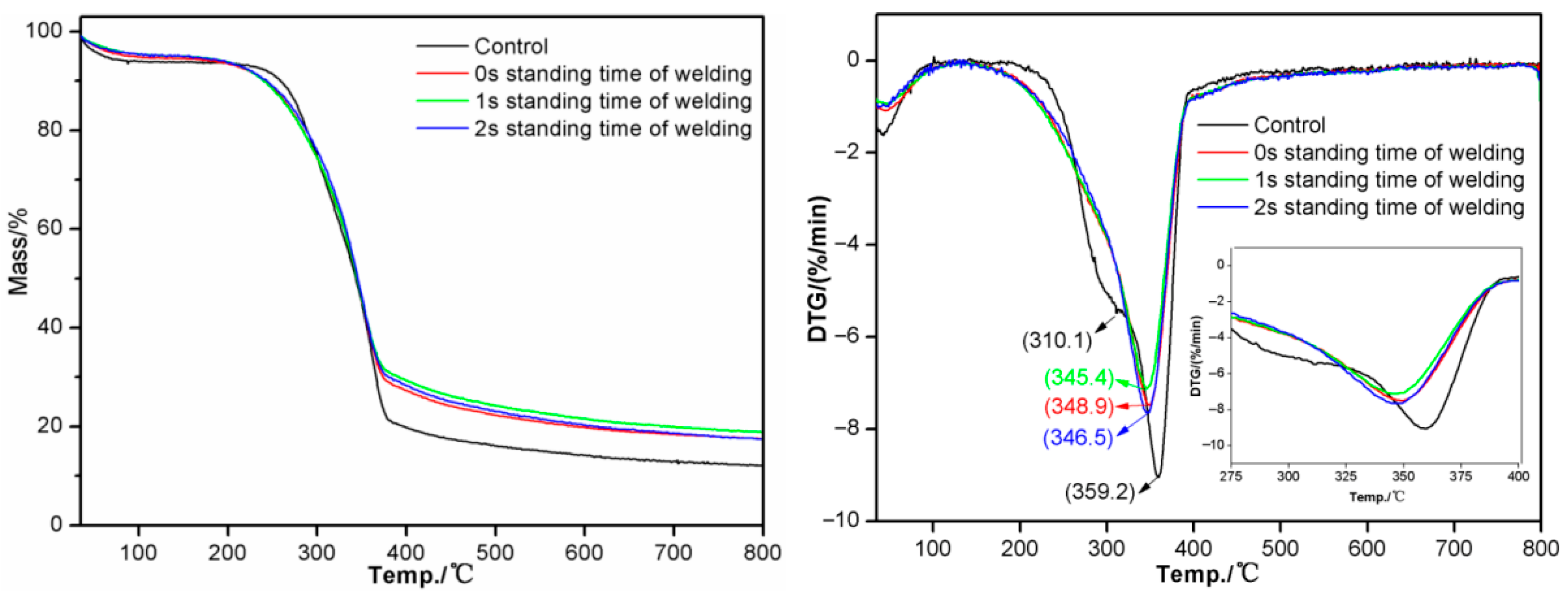

3.11. TG/DTG Analysis

4. Conclusions

- This study successfully achieved its objective to systematically evaluate rotary welding parameters for eucalyptus wood and characterize their effects on joint performance. The central results demonstrate clear optimization pathways: the tenon-to-pilot hole diameter ratio of 1:0.8 maximized connection strength at 3.79 MPa, zero-second dwell time proved optimal as longer durations caused thermal degradation reducing strength by over 50%, and increasing welding depth to 25 mm significantly enhanced performance compared to shallower depths.

- Chemical and microstructural analyses revealed that welding-induced partial degradation of hemicellulose and cellulose led to new chemical bond formation and increased carbonyl compounds. XRD showed increased wood crystallinity, SEM confirmed tighter interfaces with enhanced mechanical interlocking, and TGA verified improved thermal stability. These integrated modifications collectively explain the mechanical performance improvements.

- Several limitations should be noted. The study examined only eucalyptus as substrate wood, limiting generalization to other species. Only selected process parameters were evaluated, leaving additional factors unexplored. Furthermore, all testing was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, which may not fully replicate industrial manufacturing or long-term field performance.

- Future research directions should include testing rotary welding on other wood species to validate parameter transferability, and evaluating joint performance under varying humidity conditions to assess moisture resistance. Additionally, testing under real-world usage loads would verify durability in practical structural applications.

- Despite these limitations, the findings provide practical guidance for optimizing rotary welding protocols in sustainable wood manufacturing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, C.; Zhou, N.; Guo, P.R.; Li, M.; Wang, F.; Li, J.J.; Han, Y.F.; Wu, Z.G.; Lu, W.J. Innovative barnacle-inspired organic–inorganic hybrid magnesium oxychloride cement composites with exceptional mechanical strength and water resistance. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, L.J.; Xiong, X.Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, N.; Qiu, Z.J.; Jin, T.; Chen, Y.F. Preparation of a novel melamine formaldehyde resin with palmitoylated melamine involved and its functional coating. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2024, 132, 103670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.C.; Li, Z.S.; Wei, R.Z.; Ma, T.H.; Xie, X.B.; Yang, G.E.; Qing, Y.; Li, X.G.; Kuang, C.T.; et al. A high-strength, environmental-friendly, and multifunctional soy protein adhesive inspired by biomineralization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 451, 138753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yu, L.P.; Li, L.F.; Liang, J.K.; Wu, Z.G.; Yang, G.F.; Yin, S.; Gong, F. Comparison of nail-holding performance of Pinus massoniana and Cunninghamia lanceolata dimension lumber based on round steel nails. BioResources 2024, 19, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, B.; Wei, P.; Wang, L. Cross-laminated timber (CLT) in China: A state-of-the-art. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2019, 4, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, A.; Leban, J.M.; Kanazawa, F.; Properzi, M.; Pichelin, F. Wood dowel bonding by high-speed rotation welding. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2004, 18, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leban, J.M.; Pizzi, A.; Properzi, M.; Pichelin, F.; Gelhaye, P.; Rose, C. Wood welding: A challenging alternative to conventional wood gluing. Scand. J. For. Res. 2005, 20, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedara, A.K.A.; Chianella, I.; Endrino, J.L.; Zhang, Q. Adhesiveless Bonding of Wood—A Review with a Focus on Wood Welding. BioResources 2021, 16, 6448–6470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Lu, H.Y.; Zheng, Y.L.; Tian, Y. Tribological properties of the rotary friction welding of wood. Tribol. Int. 2022, 167, 107396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornuault, P.H.; Carpentier, L. Tribological mechanisms involved in friction wood welding. Tribol. Int. 2019, 141, 105963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthoff, B.; Schaaf, A.; Hentschel, H. Method for Joining Wood. DE 19620273, 27 November 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri, H.R.; Pizzi, A.; Leban, J.M.; Delmotte, L.; Lindgren, O.; Vaziri, M. Causes for the improved water resistance in Pine wood Linear welded joints. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2011, 25, 1987–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, M.; Lindgren, O.; Pizzi, A.; Mansouri, H.R. Moisture Sensitivity of Scots Pine Joints Produced by Linear Frictional Welding. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2010, 24, 1515–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrani, P.; Pizzi, A.; Mansouri, H.R.; Leban, J.M.; Delmotte, L. Physico-chemical causes of the extent of water resistance of linearly welded wood joints. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2009, 23, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, A.; Mansouri, H.R.; Leban, J.M.; Delmotte, L.; Pichelin, F. Enhancing the exterior performance of wood joined by linear and rotational welding. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2011, 25, 2717–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Lu, H.Y.; Zheng, Y.L.; Tian, Y. Tribological and mechanical properties of wood dowel rotation welding with different additives. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2023, 37, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, A.; Despres, A.; Mansouri, H.R.; Leban, J.M.; Rigolet, S. Wood joints by through-dowel rotation welding: Microstructure 13C-NMR and water resistance. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2006, 20, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Gao, Y.; Yi, S.; Ni, C.; Zhang, J.; Luo, X. Mechanics and pyrolysis analyses of rotation welding with pretreated wood dowels. J. Wood Sci. 2017, 63, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Li, D.; Xu, X.X.; Li, Q.; Yu, D.Y.; Wu, Z.G.; Liang, J.K.; Peng, J.; Gu, W.; Zhao, X.; et al. Effects of Dowel Rotation Welding Conditions on Connection Performance for Chinese Fir Dimension Lumbers. Forests 2024, 15, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmotte, L.; Ganne-Chedeville, C.; Leban, J.M.; Pizzi, A.; Pichelin, F. CP-MAS 13C-NMR and FT-IR investigation of the degradation reactions of polymer constituents in wood welding. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2007, 93, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.X.; He, J.R.; Yang, J.W.; Sun, Q.Y.; Lu, X.N.; Zhang, Z.F. Study on Water Resistance Improvement of Wood Dowel Rotation Welding Joints. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2023, 43, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitzthum, K.; Feist, F.; Krenke, T. Wood Dowel Welding Without a Pilot Hole–An Investigation into Joining Low-Density Plywood. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2025, 83, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Viana, A.C.; Maduro de Campos, C.E.; Dias de Moraes, P.; Lindolfo Weingaertner, W. Bond-line Strength, Chemical Properties and Cellulose Crystallinity of Welded Pine and Itauba Wood. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 19, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covelli, C.; Yuan, S.; Grewell, D.; Schmidt-Rohr, K. Structural Changes from Vibration Welding of Maple and Pine Woods Analyzed by Solid-State NMR. Weld. World 2022, 66, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.H.; Liu, K.; Zhao, Y.H.; Bouchaïr, A. Pullout Resistance of Densified Wood Dowel Welded by Rotation Friction. J. Mater. Civil Eng. 2022, 34, 4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biwole, J.; Biwole, A.; Mfomo, J.; Segovia, C.; Pizzi, A.; Chen, X.Y.; Fongnzossie, E.; Ateba, A.; Meausoone, P.J. Causes of Differential Behavior of Extractives on the Natural Cold Water Durability of the Welded Joints of Three Tropical Woods. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2021, 36, 1314–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.W.; He, J.R.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhang, Z.F. A Method of Using a Combination of Multiple Chemical Additives to Improve the Performance of Wood (Round Tenon) Rotary Friction Welding. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2025, 83, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 1927.21-2022; Test Methods for Physical and Mechanical Properties of Small Clear Wood Specimens—Part 21: Determination of Nail and Screw Holding Power. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Kanazawa, F.; Pizzi, A.; Properzi, M.; Delmotte, L.; Pichelin, F. Parameters influencing wood-dowel welding by high-speed rotation. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2005, 19, 1025–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleville, B.; Amirou, S.; Pizzi, A.; Barbara, O. Optimization of Wood Welding Parameters for Australian Hardwood Species. BioResources 2016, 12, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.J.; Pizzi, A. Schichtholz aus Holz-und Bambuslagen verbunden durch lineares Vibrations-Reibschweißen. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2013, 71, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Župčić, I.; Vlaović, Z.; Domljan, D.; Grbac, I. Influence of Various Wood Species and Cross-Sections on Strength of a Dowel Welding Joint. Drv. Ind. 2014, 65, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Castro, D.; Eres-Castellanos, A.; Vivas, J.; Caballero, F.G.; San-Martín, D.; Capdevila, C. Morphological and crystallographic features of granular and lath-like bainite in a low carbon microalloyed steel. Materi. Charact. 2022, 184, 111703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyota, M.; Mikami, Y.; Hashimoto, T.; Taniguchi, K.; Ikeda, R.; Mochizuki, M. The effect of martensitic transformation on residual stress in resistance spot welded high-strength steel sheets. J. Alloy Compd. 2012, 577, S684–S689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Deng, X.; Li, L.; Xi, X.; Tian, M.; Yu, L.; Zhang, B. Effects of heat treatment on interfacial properties of Pinus Massoniana wood. Coatings 2021, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Kuo, P.C. Isothermal torrefaction kinetics of hemicellulose, cellulose, lignin and xylan using thermogravimetric analysis. Energy 2011, 3, 6451–6460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, S.R.; Zheng, Y.; Luo, Z.Y.; Cen, K.F. Mechanism study of wood lignin pyrolysis by using TG-FTIR analysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2008, 82, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.F.; Wang, S.R.; Ma, X.Q. Mechanism Study of Cellulose Rapid Pyrolysis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2004, 43, 5605–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, J.; Zhong, X.; Yang, Y.; Yang, G.; Yin, S.; Gong, F.; Chen, C.; Li, H.; Meng, T.; Jian, Y.; et al. Improving the Strength of Eucalyptus Wood Joints Through Optimized Rotary Welding Conditions. Materials 2025, 18, 5596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245596

Liang J, Zhong X, Yang Y, Yang G, Yin S, Gong F, Chen C, Li H, Meng T, Jian Y, et al. Improving the Strength of Eucalyptus Wood Joints Through Optimized Rotary Welding Conditions. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245596

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Jiankun, Xiao Zhong, Yuqi Yang, Guifen Yang, Shuang Yin, Feiyan Gong, Chuchu Chen, Huali Li, Tong Meng, Yulan Jian, and et al. 2025. "Improving the Strength of Eucalyptus Wood Joints Through Optimized Rotary Welding Conditions" Materials 18, no. 24: 5596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245596

APA StyleLiang, J., Zhong, X., Yang, Y., Yang, G., Yin, S., Gong, F., Chen, C., Li, H., Meng, T., Jian, Y., Li, D., Long, C., Song, Z., & Wu, Z. (2025). Improving the Strength of Eucalyptus Wood Joints Through Optimized Rotary Welding Conditions. Materials, 18(24), 5596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245596