Multiscale Viscoelastic Analysis of Asphalt Concrete

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Reliable recognition of the AC microstructure in 2D using the high-quality image processing;

- Carrying out a viscoelastic analysis with a Burgers material model used for the mastic phase;

- Facilitating the analysis with the RVE-based local evaluation of the effective parameter tensor.

2. Materials and Methods

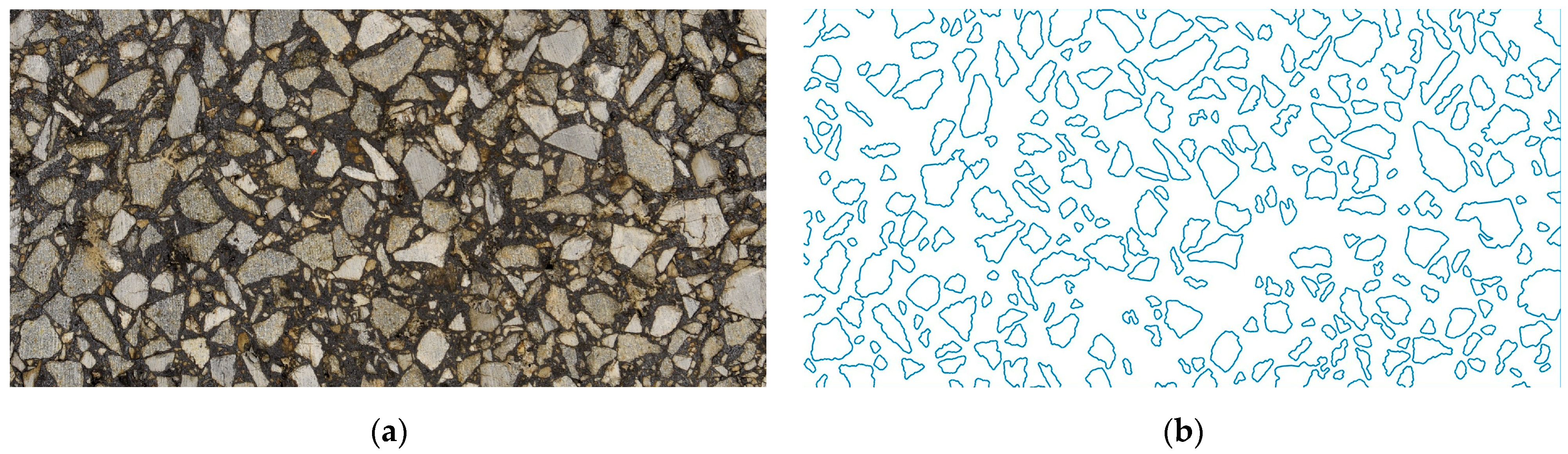

2.1. AC Specimens and High-Quality Images

2.2. Microstructure Geometry Recognition

- Taking of the high-quality images with the specimens dusted off, cleaned and light adjusted properly in order to eliminate any factors that can potentially reduce the quality of the image;

- Converting truecolor images to the grayscale based on the intensity (see [14] for details on the intensity function used);

- Adaptive binarization of the grayscale image (with the sensitivity parameter set as 0.65 in this study);

- Removing holes, filtering (removing inclusions below the 2 mm threshold) and other minor processing (e.g., erosion) to obtain the binary image of the biphasic domain;

- Segmentation and boundary of each aggregate particle detection;

- Optionally, some processing of the boundary shape. Herein, the error-controlled algorithm developed in [14] was used to simplify the description of the microstructure geometry. Practically, up to five iterations were used for every inclusion due to the selected precision in area reconstruction equal to 10%. As demonstrated in [14], this simplification is justified at this scale of analysis, and it introduces only negligible error to the solution. Simultaneously, the reduction in the finite element mesh density is substantial, which reduces the computational cost of the whole framework.

2.3. Constitutive Modeling

- Generalized Burgers material model comprises a number of Kelvin–Voigt and Maxwell elements linked in series;

- Consequently, the total strain can be additively decomposed into elastic , viscous and viscoelastic term ;

- Generally, the moduli are associated with the springs in the mechanical interpretation of the model; thus, they represent the elastic material behavior. The viscosities are associated with the dumpers in the mechanical representation; they model the viscous behavior of the material. Specifically, the instantaneous and recoverable material response is modeled by the Maxwell element’s spring. The irrecoverable material response is modeled by the dumper of this element. The delayed, yet recoverable, material response is modeled by the Kelvin–Voigt element (parallel combination of the spring and dumper).

- In the absence of the body forces, linearized incremental formulation of the viscoelasticity problem yields the following:

- The analysis is carried out with a division of the whole analysis period into a set of properly selected time instances—discretization of the time domain with intervals ;

- The initial solution increment at every time instance is the elastic solution increment; it is equivalent to the solution of Equation (1) without its rightmost term;

- Inelastic strain increments are computed according to Equations (2) and (3);

- The load vector contributions (the rightmost term in Equation (1)) are computed elementwise and assembled;

- Equation (1) is solved in its full form;

- Iterative procedure is repeated to obtain the equilibrium;

- Final incremental quantities of displacements, strains and stresses are saved and the response at the next time instance is evaluated.

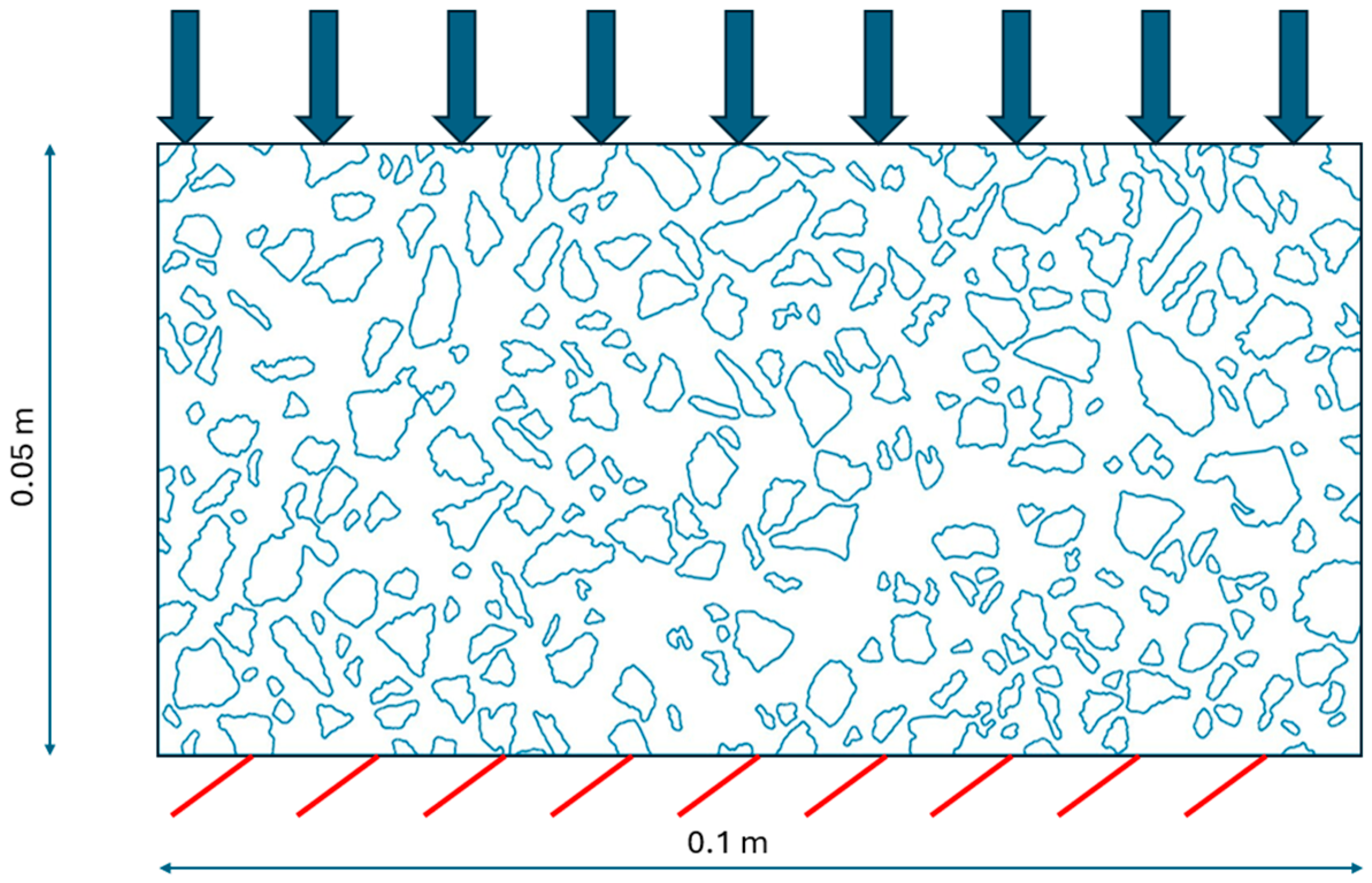

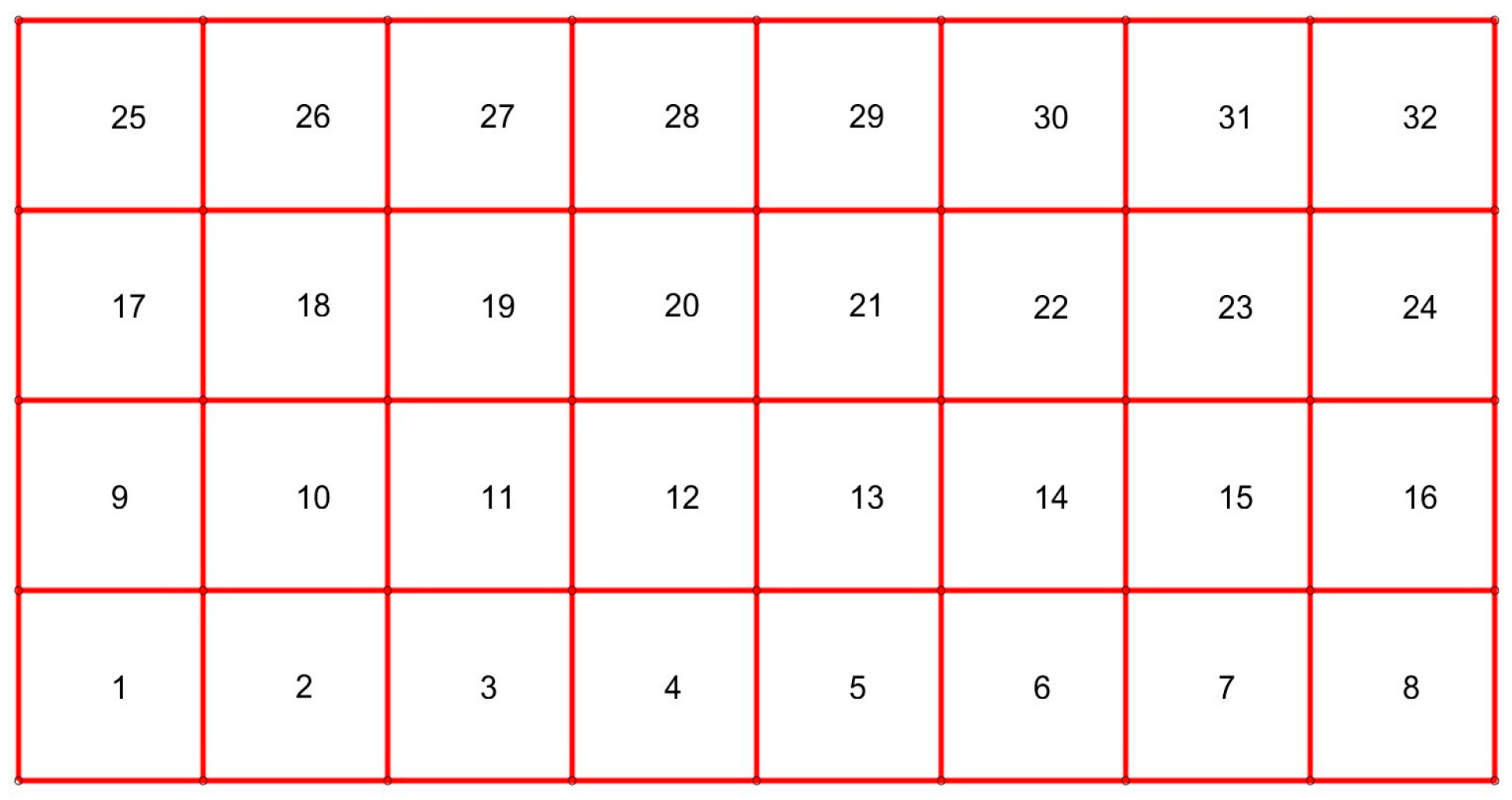

2.4. Numerical Homogenization of the Burgers Material

- In this paper, we extend the findings of the study [25] in the context of the viscoelastic analysis in the small strains range. Herein, we use only the linear approximation in the finite element analysis and do not modify the RVE boundary condition, which was the main aspect of that paper.

- In the “offline” step, evaluate the effective tensors of material properties for every RVE associated with a respective Gauss point—this is performed only once;

- In the “online” step, solve the macroscale problem at a specific time instance and compute the strains at every Gauss point;

- Use the Gauss points’ strains to impose the kinematic boundary conditions for the corresponding RVEs (, where denotes the displacements along the boundary, is the average stress tensor within the macro element and stands for the point position);

- Solve these local BVPs using Equation (1) (for a given time instance) and compute average inelastic strains;

- Use these inelastic strains to update the load vector in Equation (1) at the macroscale level.

3. Results

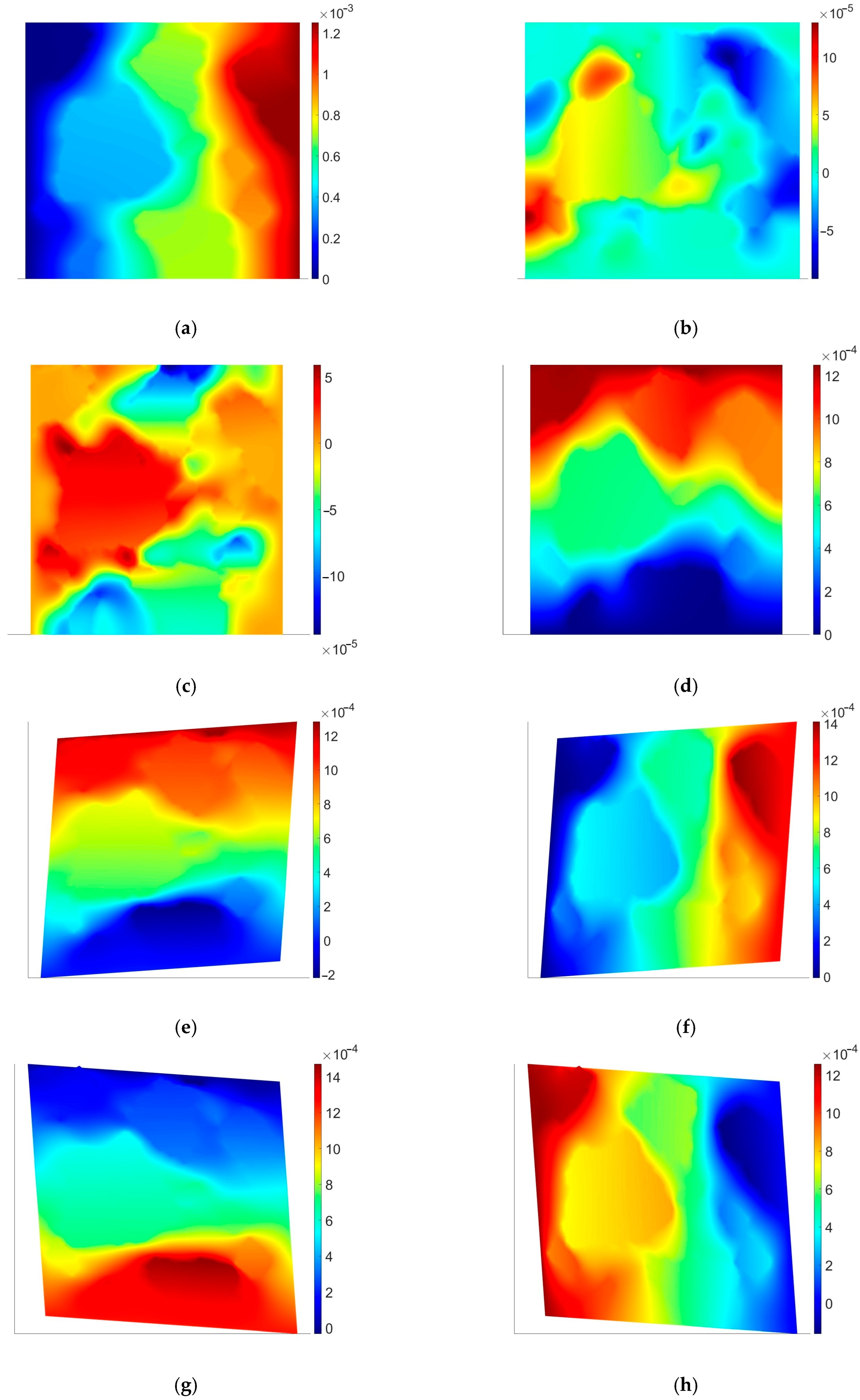

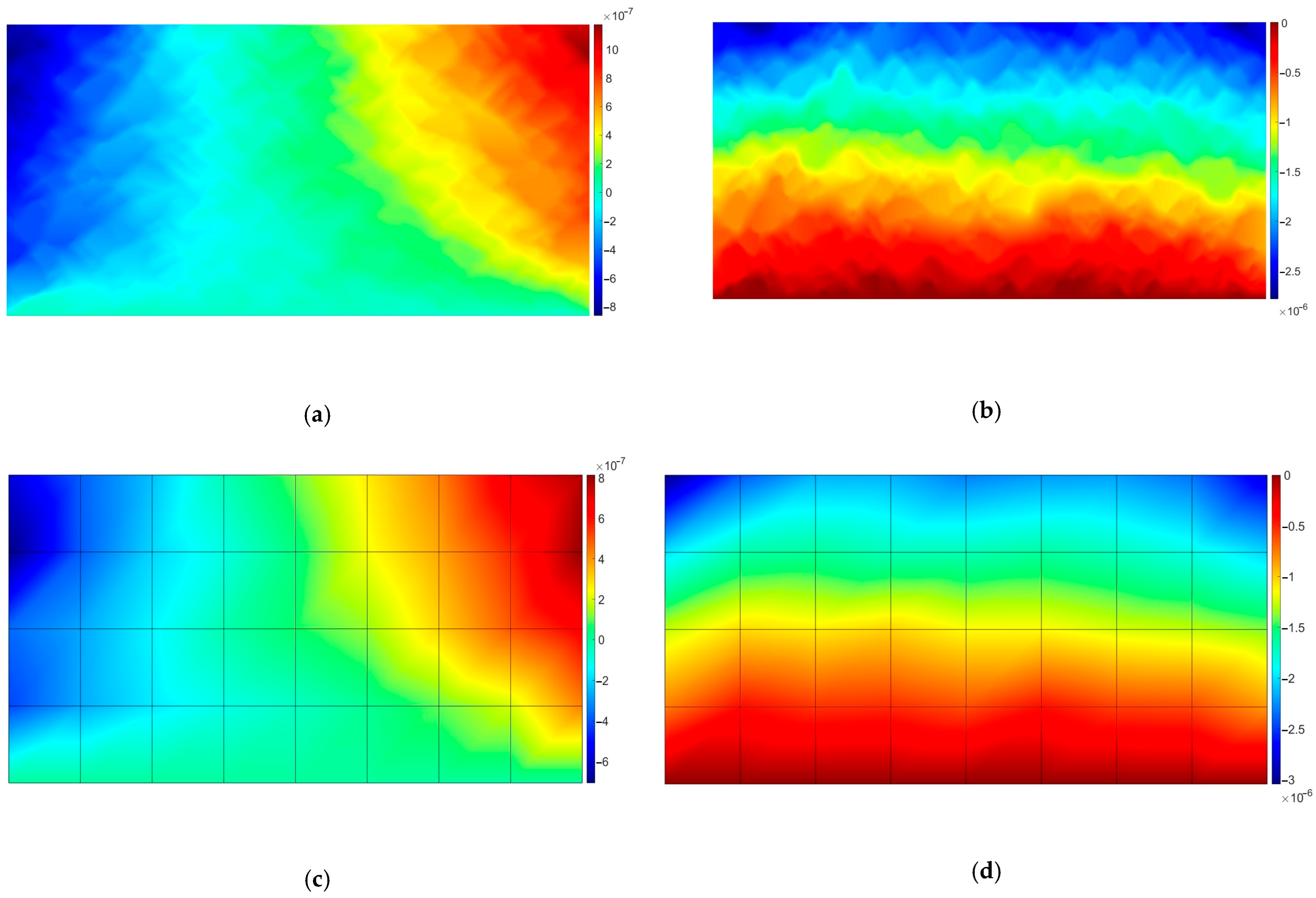

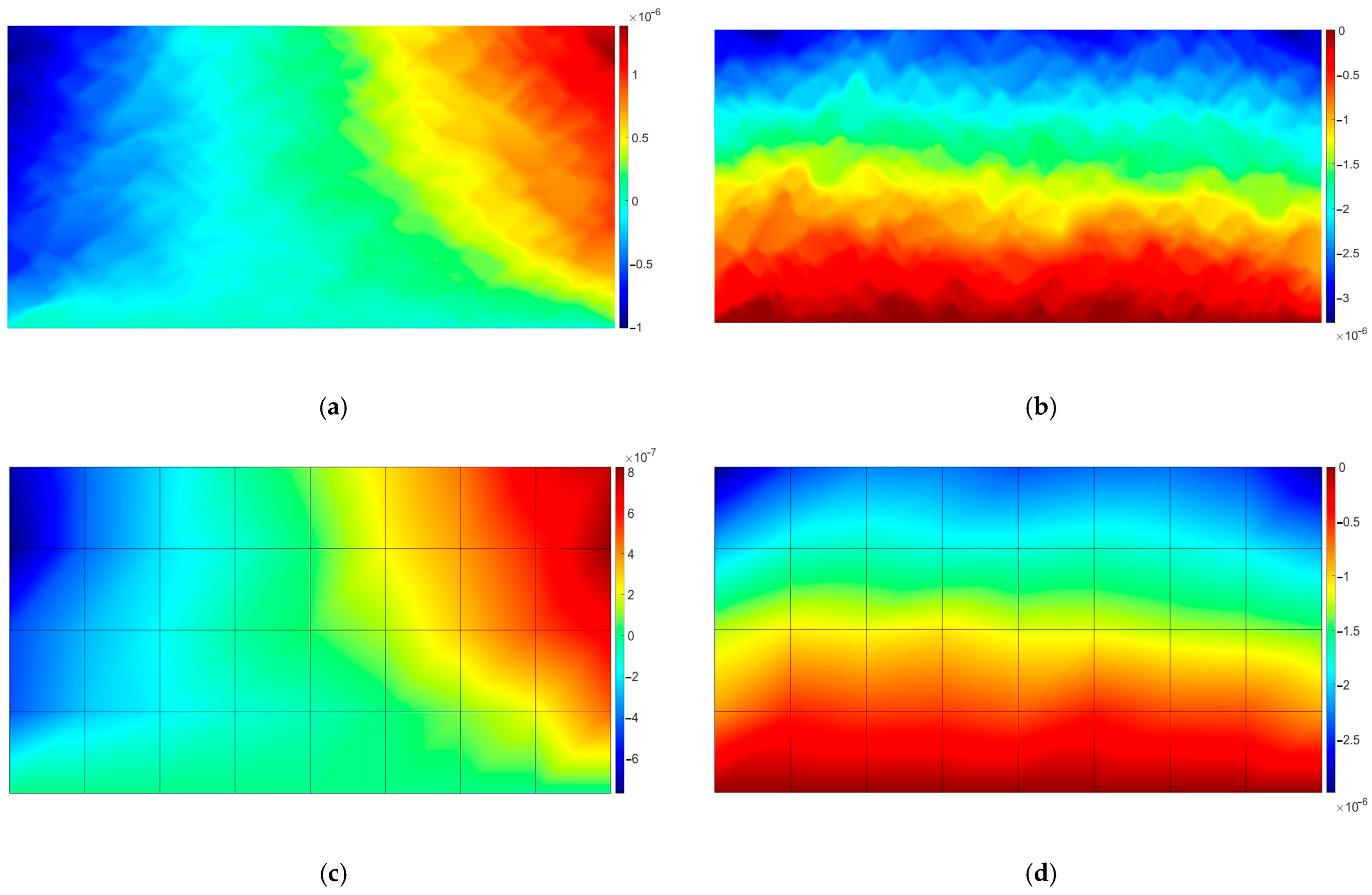

3.1. Linear Elastic Test

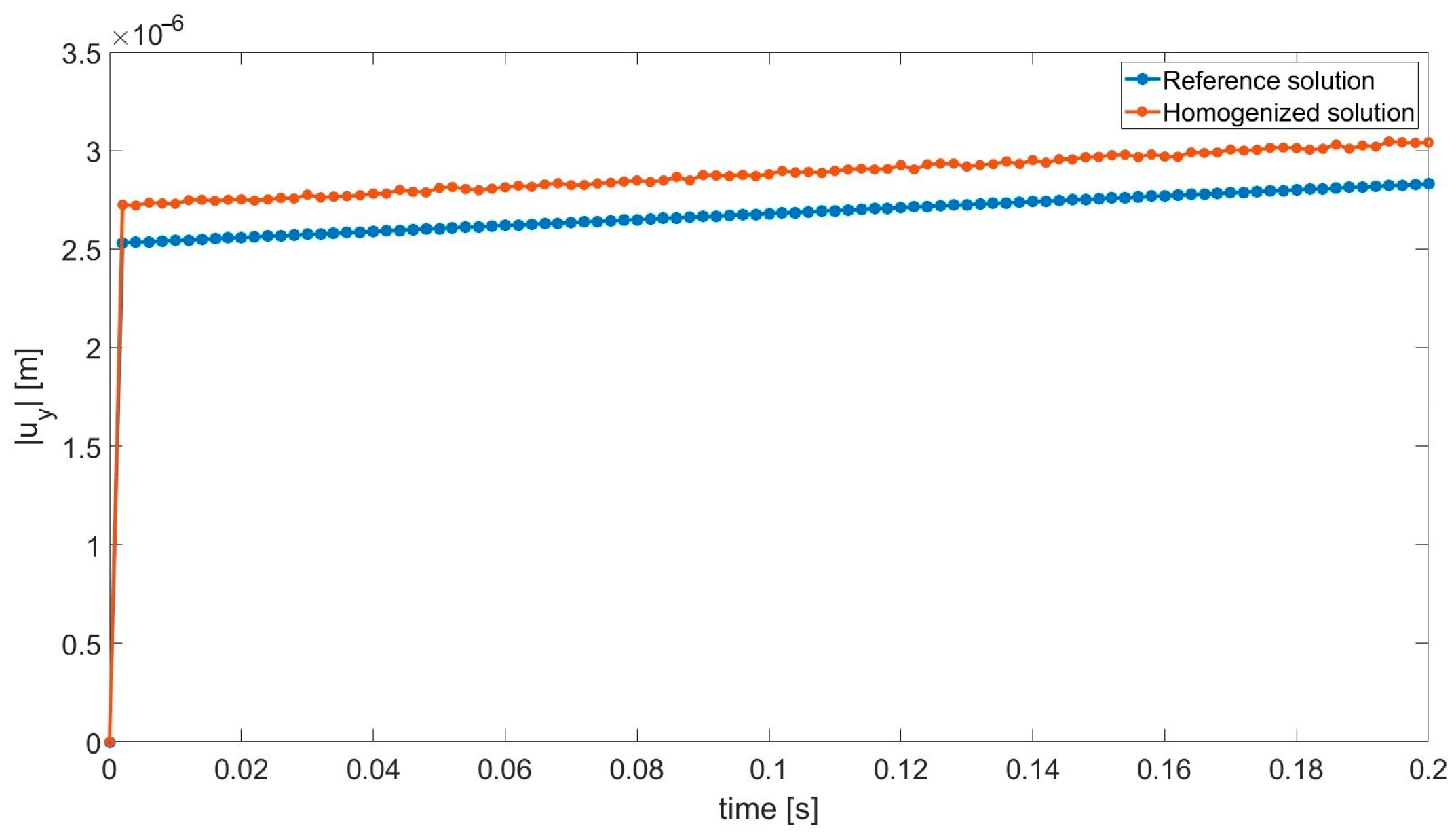

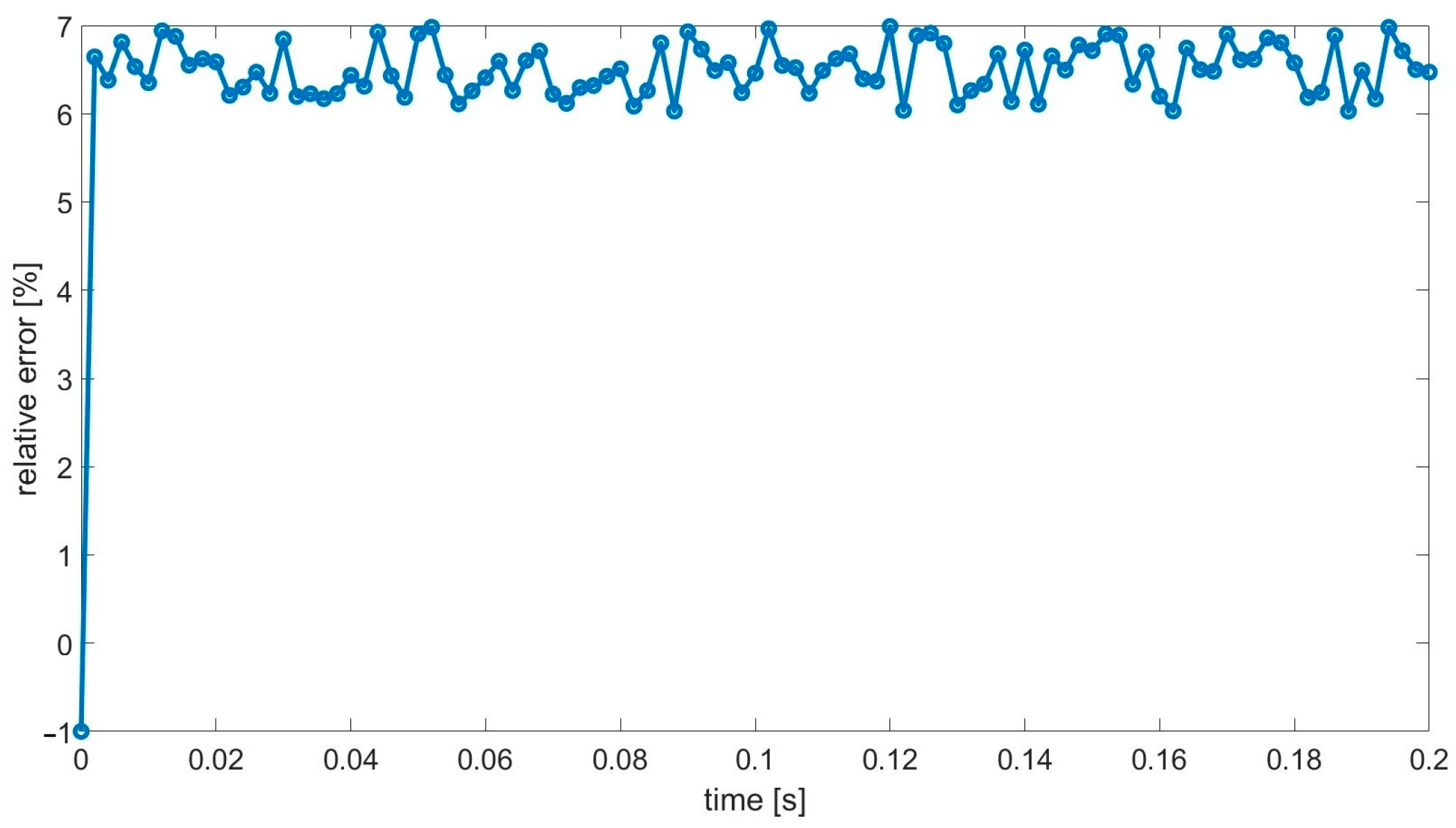

3.2. Viscoelastic Test

4. Discussion

- The microstructure geometry is very irregular; it does not exhibit periodicity;

- The dimensions of the specimens (corresponding to the thicknesses of the pavement layers) make it difficult to easily fulfill the requirement of the scale separation in context of the RVE size—in the numerical tests presented in this paper, the findings of [25] were used to specify the optimal RVE size;

- The value of the main parameter (the Young modulus) exhibits a very large difference between the phases of the specimen.

- The relative homogenization error measured in the maximum norm was equal to 6.8% and 6.9% for the elasticity and viscoelasticity problem, respectively;

- The reduction in the NDOF is equal to about 510 times—it is particularly promising in the context of viscoelastic analysis;

- The relative error seems not to accumulate drastically—in the presented results, it oscillated around approximately 6.5% for the selected point;

- The effective tensor of material parameters is in line with a rough approximation using a simple mixture rule.

5. Conclusions

- Image processing is a versatile tool for microstructure recognition;

- Multiscale analysis of asphalt concrete and other asphalt mixtures is necessary to investigate the microscale phenomena efficiently;

- Numerical homogenization in the presented form can be an effective method of viscoelastic analysis in the small strain range—it is the main novelty of the paper;

- Special attention should be paid to the accurate selection of the RVE size in such an analysis;

- Further research efforts should consider 3D analysis using the proposed framework with the microstructure recognized using the XRCT scans.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Asphalt concrete |

| BVP | Boundary value problem |

| CH | Computational homogenization |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| FEM | Finite element method |

| GPR | Ground penetrating radar |

| ITZ | Interface transition zone |

| NDOF | Number of degrees of freedom |

| NH | Numerical homogenization |

| RVE | Representative volume element |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| XRCT | X-ray computed tomography |

References

- Stopka, G.; Gieleta, R.; Panowicz, R.; Wałach, D.; Kaczmarczyk, G.P. High Strain Rate Response of Sandstones with Different Porosity under Dynamic Loading Using Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar (SHPB). Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarczyk, G.P.; Wałach, D. New Insights into Cement-Soil Mixtures with the Addition of Fluidized Bed Furnace Bottom Ashes. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarczyk, G.P.; Wałach, D.; Natividade-Jesus, E.; Ferreira, R. Change of the Structural Properties of High-Performance Concretes Subjected to Thermal Effects. Materials 2022, 15, 5753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Wu, S.; Xiao, F.; Pang, L.; Xiao, Y. Conductive asphalt concrete: A review on structure design, performance, and practical applications. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2014, 26, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elseifi, M.A.; Abdel-Khalek, A.M.; Gaspard, K.; Zhang, Z.; Ismail, S. Evaluation of continuous deflection testing using the rolling wheel deflectometer in Louisiana. J. Transp. Eng. 2012, 138, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. Distribution of the temperature field in a pavement structure. In Structural Behavior of Asphalt Pavements; Butterworth-Heinemann: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 61–177. ISBN 9780128499085. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Wei, K.; Wei, J.; Han, W.; Zhang, X.; Hu, G.; Wei, S.; Niu, L.; Chen, K.; Fu, Z.; et al. Research on the Road Performance of Asphalt Mixtures Based on Infrared Thermography. Materials 2022, 15, 4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedret Rodés, J.; Martínez Reguero, A.; Pérez-Gracia, V. GPR Spectra for Monitoring Asphalt Pavements. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Song, X.; Weng, C.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Z. A Hybrid Method Combining Voronoi Diagrams and the Random Walk Algorithm for Generating the Mesostructure of Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Sun, Y.; Gong, H.; Chen, J. Fast 3D Voronoi and Voxel–Based Mesostructure Modeling Method for Asphalt Concrete. J. Eng. Mech. 2023, 149, 7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; Yang, Z.J.; Yates, J.R.; Jivkov, A.P.; Zhang, C. Monte Carlo simulations of mesoscale fracture modelling of concrete with random aggregates and pores. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 75, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Cao, M. Mesoscale Mechanical Analysis of Concrete Based on a 3D Random Aggregate Model. Coatings 2025, 15, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczak, M.; Cecot, W. Towards asphalt concrete modeling by the multiscale finite element method. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2020, 171, 103367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczak, M.; Jaworska, I.; Tekieli, M. 2D Digital Reconstruction of Asphalt Concrete Microstructure for Numerical Modeling Purposes. Materials 2022, 15, 5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middendorf, M.; Umbach, C.; Liu, J.; Koenders, E.A.B. Contact area analysis of an asphalt-concrete boundary layer with X-ray computed tomography imaging. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 430, 136497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleri, E.; Harvey, J.T.; Yang, K.; Boone, J.M. Investigation of asphalt concrete rutting mechanisms by X-ray computed tomography imaging and micromechanical finite element modeling. Mater. Struct. 2013, 46, 1027–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, A.; Boshoff, W.P. A review of X-ray computed tomography of concrete and asphalt construction materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 199, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashidhar, N. X-Ray Tomography of Asphalt Concrete. Transp. Res. Rec. 1999, 1681, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, B.; Tan, Y. Meso-Structural Modeling of Asphalt Mixtures Using Computed Tomography and Discrete Element Method with Indirect Tensile Testing. Materials 2025, 18, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, D.; Yao, T.; Hu, Y.; Dou, H. Evolution of clogging of porous asphalt concrete in the seepage process through integration of computer tomography, computational fluid dynamics, and discrete element method. Comput.-Aided Civil Infrastruct. Eng. 2025, 40, 1652–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madej, Ł.; Sitko, M.; Fular, A.; Sarzyński, R.; Wermiński, M.; Perzyński, K. Capturing Local Material Heterogeneities in Numerical Modelling of Microstructure Evolution. J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 21, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüller, T.; Jänicke, R.; Steeb, H. Nonlinear modeling and computational homogenization of asphalt concrete on the basis of XRCT scans. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 109, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, F.; Chow, C.L.; Lau, D. A Review on Multiscale Modeling of Asphalt: Development and Applications. Multiscale Sci. Eng. 2022, 4, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Cucalon, L.; Rahmani, E.; Little, D.N.; Allen, D.H. A multiscale model for predicting the viscoelastic properties of asphalt concrete. Mech. Time-Depend. Mater. 2016, 20, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczak, M.; Oleksy, M. Higher order numerical homogenization in modeling of asphalt concrete. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2024, 62, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvas, D.; Stefanou, G.; Papadrakakis, M. Determination of RVE size for random composites with local volume fraction variation. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2016, 305, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelissou, C.; Baccou, J.; Monerie, Y.; Perales, F. Determination of the size of the representative volume element for random quasi-brittle composites. Int. J. Solid Struct. 2009, 46, 2842–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, I.; Brekelmans, W.; Geers, M. Computational homogenization for heat conduction in heterogeneous solids. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2008, 73, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Van Der Meer, F.P. A computational homogenization framework with enhanced localization criterion for macroscopic cohesive failure in heterogeneous materials. J. Theor. Comput. Appl. Mech. 2022, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, N.G.; Gunasegaram, D.R.; Murphy, A.B. Evaluation of computational homogenization methods for the prediction of mechanical properties of additively manufactured metal parts. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 64, 103415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hain, M.; Wriggers, P. Numerical homogenization of hardened cement paste. Comput. Mech. 2008, 42, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temizer, I.; Wriggers, P. On the computation of the macroscopic tangent for multiscale volumetric homogenization problems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2008, 198, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczak, M. Viscoelastic Analysis of Asphalt Concrete with a Digitally Reconstructed Microstructure. Materials 2024, 17, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zieliński, P.; Klimczak, M.; Tekieli, M.; Strzępek, M. An Evaluation of the Fracture Properties of Asphalt Concrete Mixes Using the Semi-Circular Bending Method and Digital Image Correlation. Materials 2025, 18, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials AASHTO. Mechanistic–Empirical Pavement Design Guide, a Manual of Practice; AASHTO: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.R. Modeling of Asphalt Concrete, 1st ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Collop, A.; Scarpas, A.; Kasbergen, C.; de Bondt, A. Development and finite element implementation of a stress dependent elasto-visco-plastic constitutive model with damage for asphalt. Transp. Res. Rec. 2003, 1832, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maio, U.; Gaetano, D.; Greco, F.; Lonetti, P.; Pranno, A. An adaptive cohesive interface model for fracture propagation analysis in heterogeneous media. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 325, 111330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadd, M.H.; Dai, Q.; Parameswaran, V.; Shukla, A. Simulation of Asphalt Materials Using Finite Element Micromechanical Model with Damage Mechanics. Transp. Res. Rec. 2003, 1832, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imoh, U.U.; Nagy, R.; Rad, M.M. Micro-mechanical characterization of polymer-modified asphalt mixtures using discrete element modelling with soft-bond and linear contact bond models. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 501, 144325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Young modulus E | 70,000 | [MPa] |

| Poisson ratio ν | 0.3 | [-] |

| Property | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Young modulus EM 1 | 700 | [MPa] |

| Young modulus EKV 2 | 120 | [MPa] |

| Poisson ratio ν | 0.3 | [-] |

| Poisson ratio equivalent νM 1 | 0.3 | [-] |

| Poisson ratio equivalent νKV 2 | 0.3 | [-] |

| Viscosity ηM 1 | 60,000 | [MPa s] |

| Viscosity ηKV 2 | 600 | [MPa s] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klimczak, M. Multiscale Viscoelastic Analysis of Asphalt Concrete. Materials 2025, 18, 5536. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245536

Klimczak M. Multiscale Viscoelastic Analysis of Asphalt Concrete. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5536. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245536

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlimczak, Marek. 2025. "Multiscale Viscoelastic Analysis of Asphalt Concrete" Materials 18, no. 24: 5536. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245536

APA StyleKlimczak, M. (2025). Multiscale Viscoelastic Analysis of Asphalt Concrete. Materials, 18(24), 5536. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245536