3D Printed Beam with Optimized Internal Structure—Experimental and Numerical Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Algorithm for Generated Structure

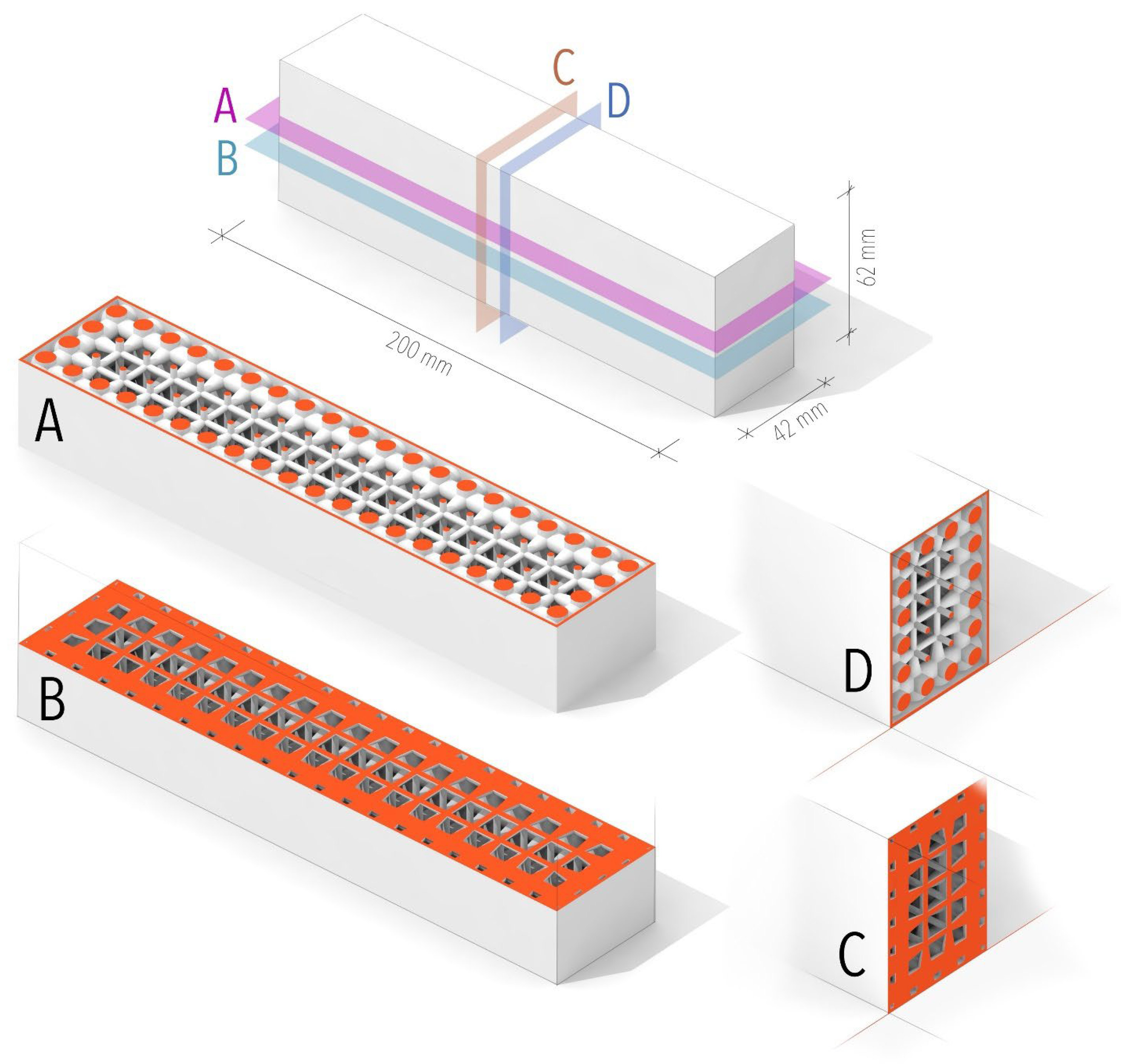

2.2. Sample Geometry and Material Properties

3. Experimental and Numerical Analysis

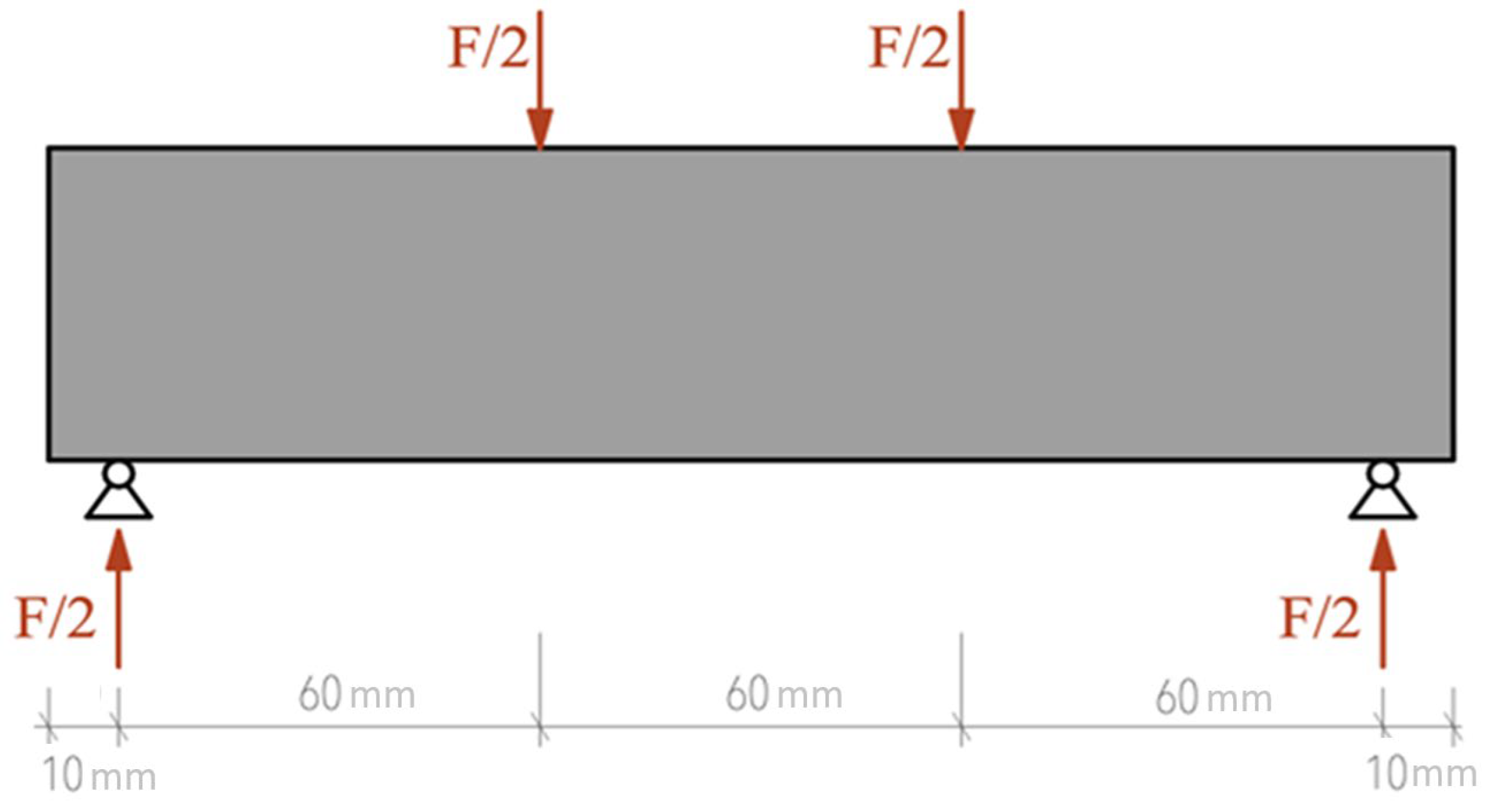

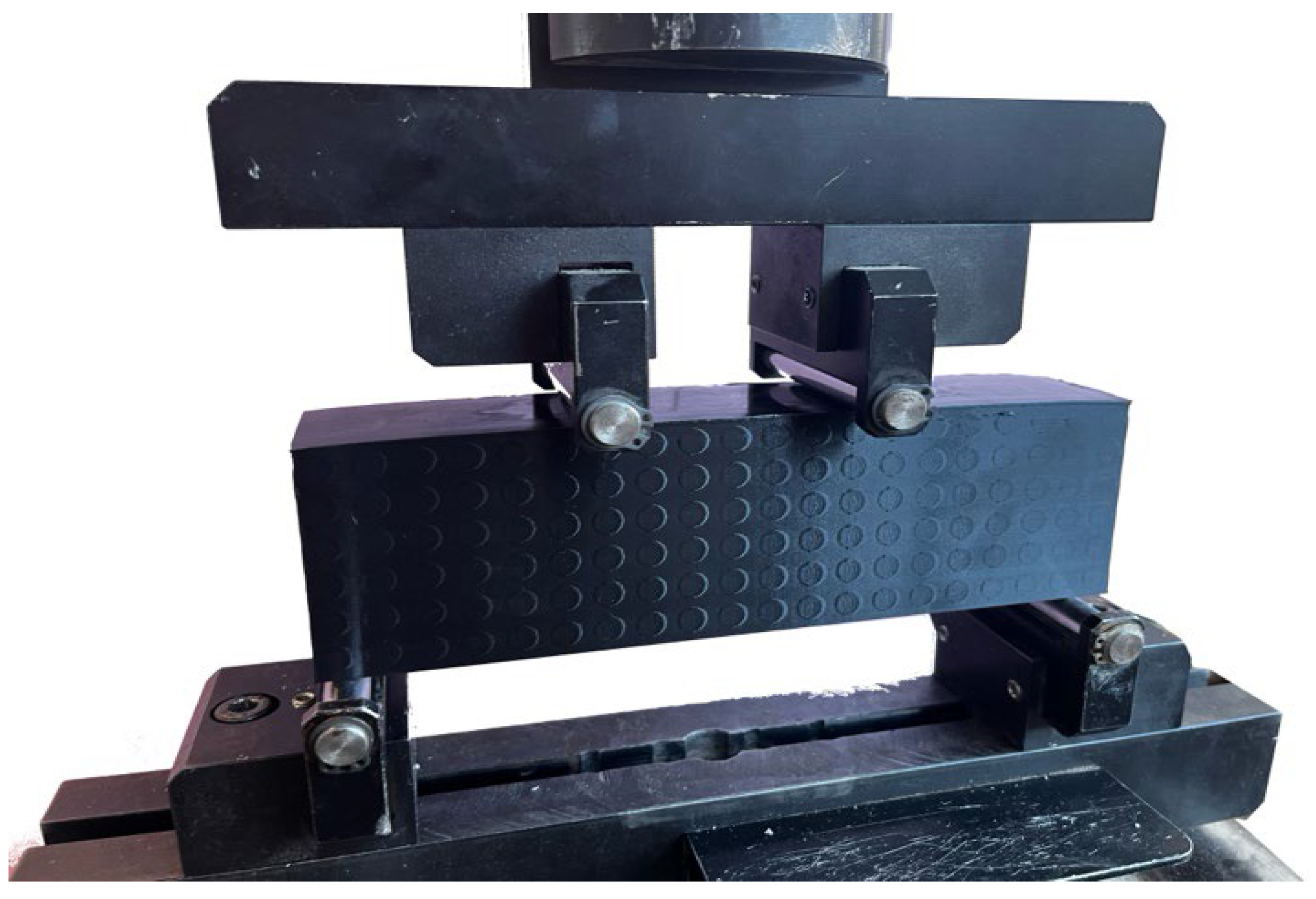

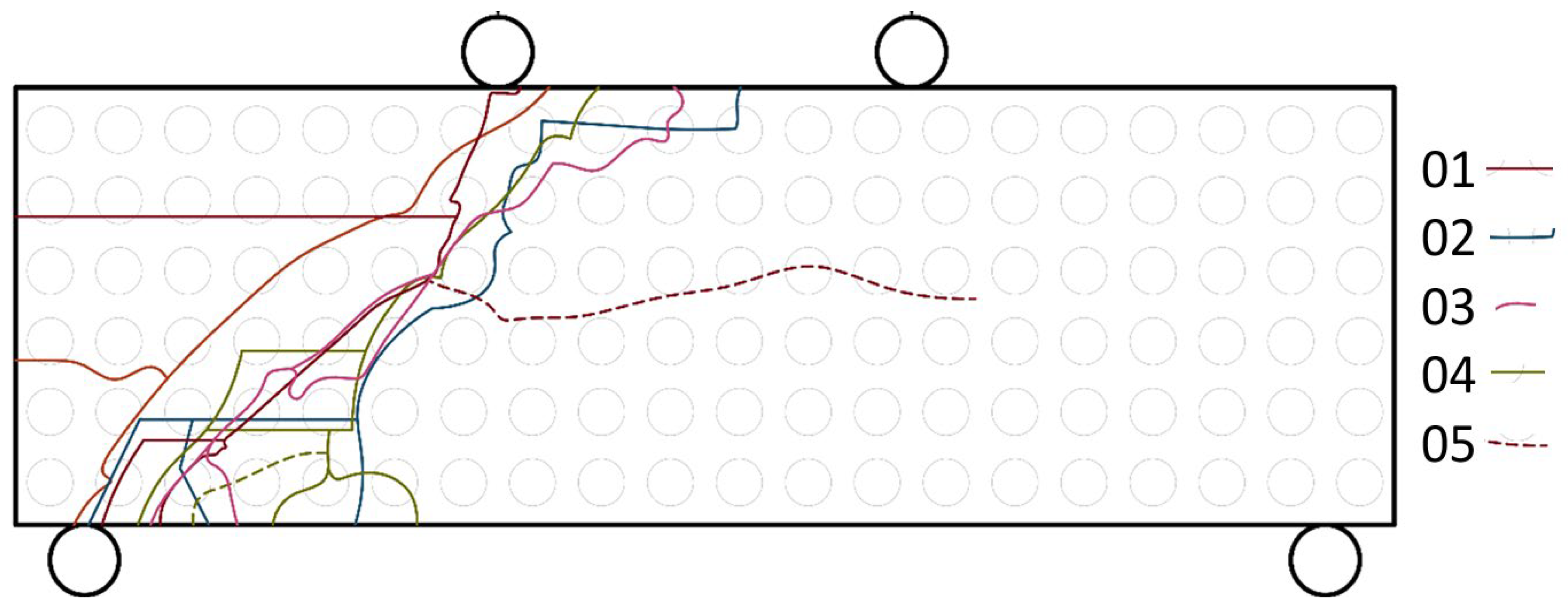

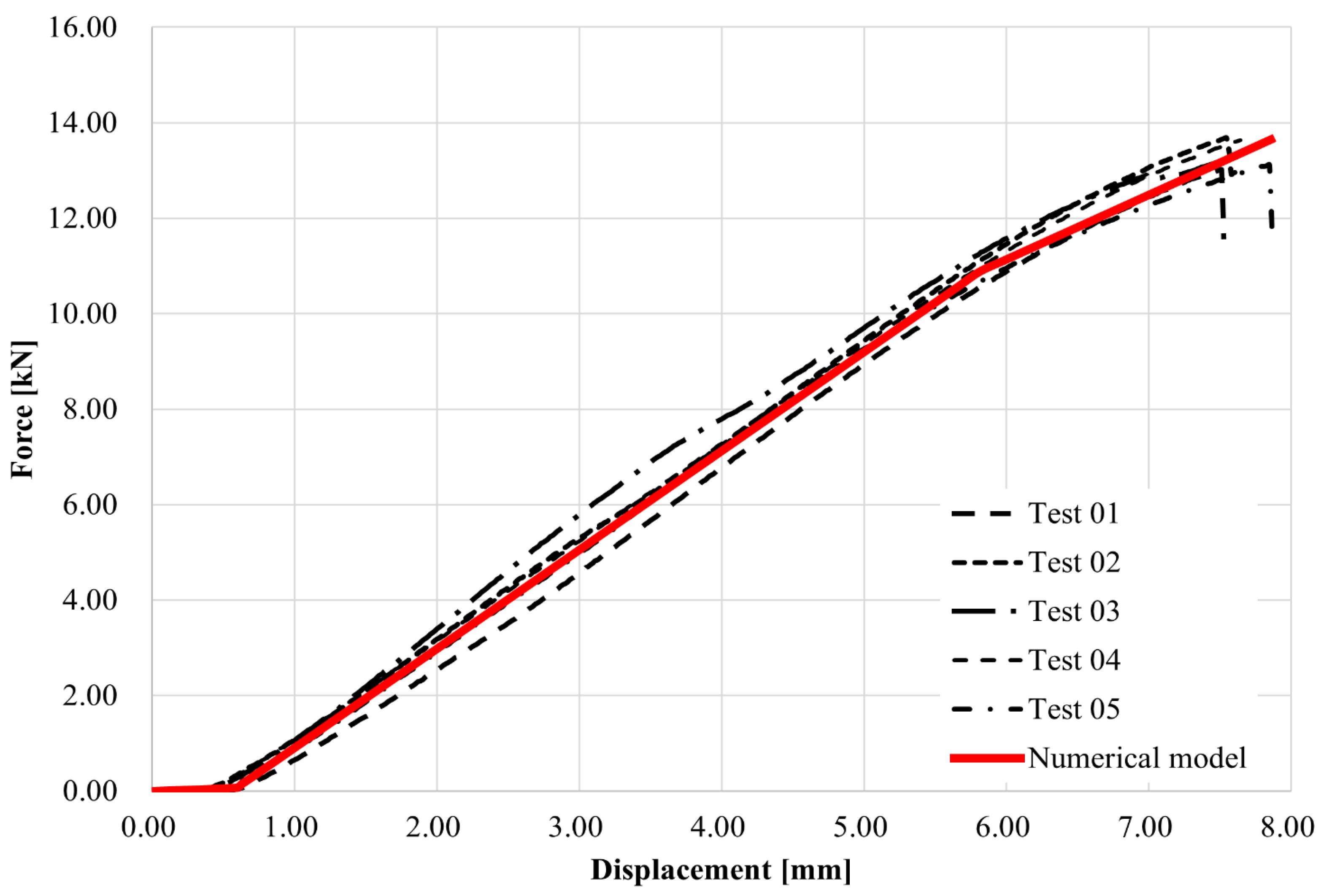

3.1. Four-Point Bending Test

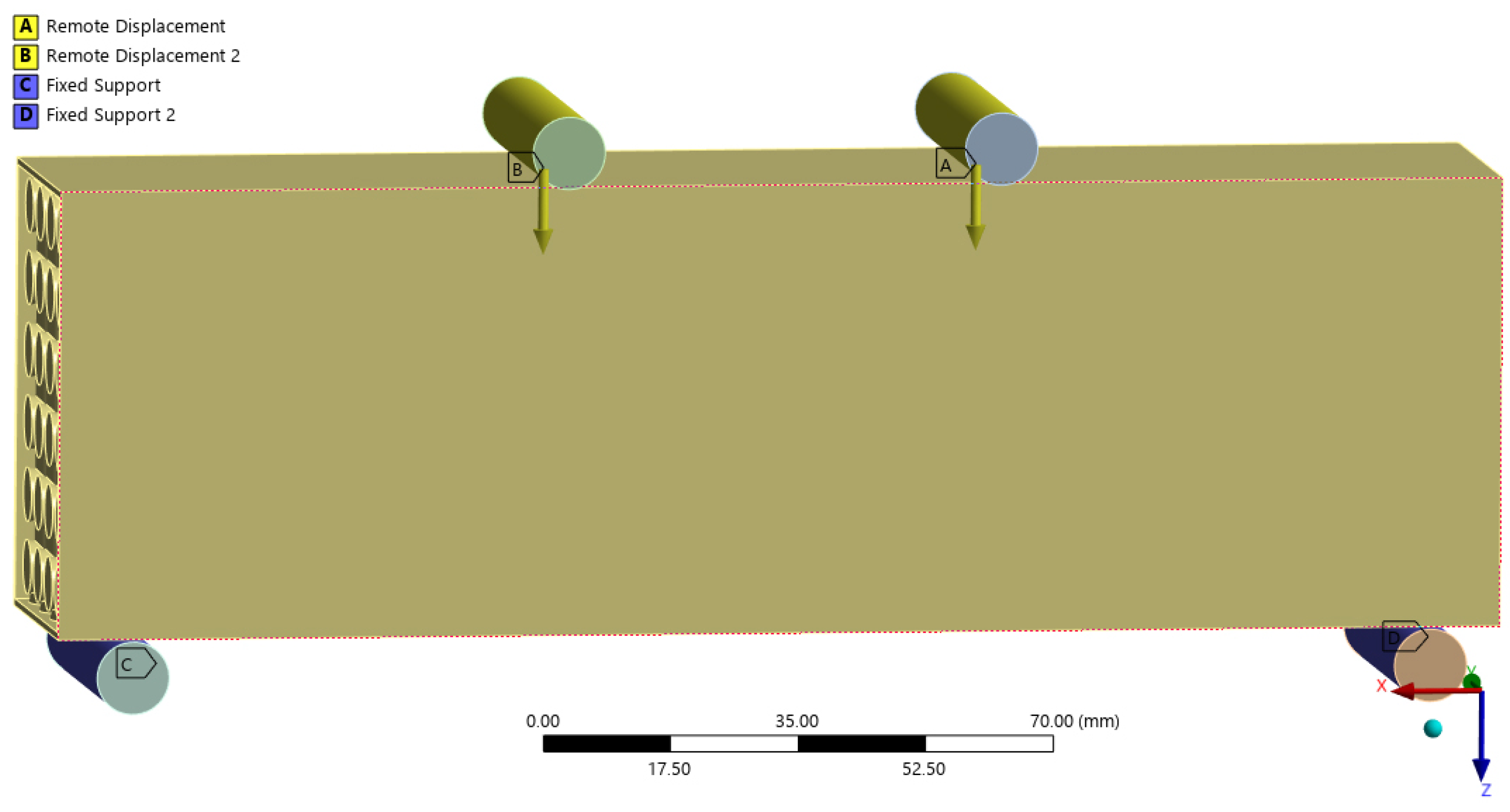

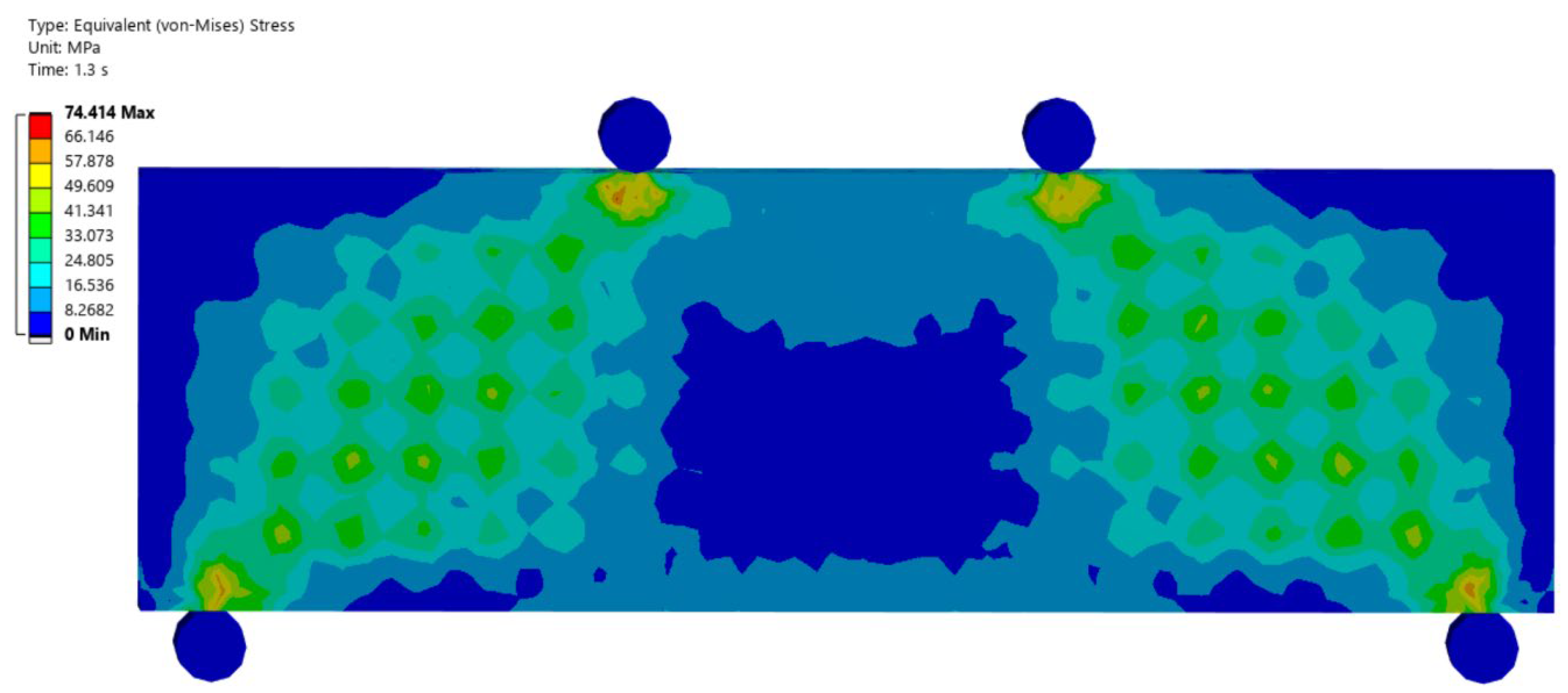

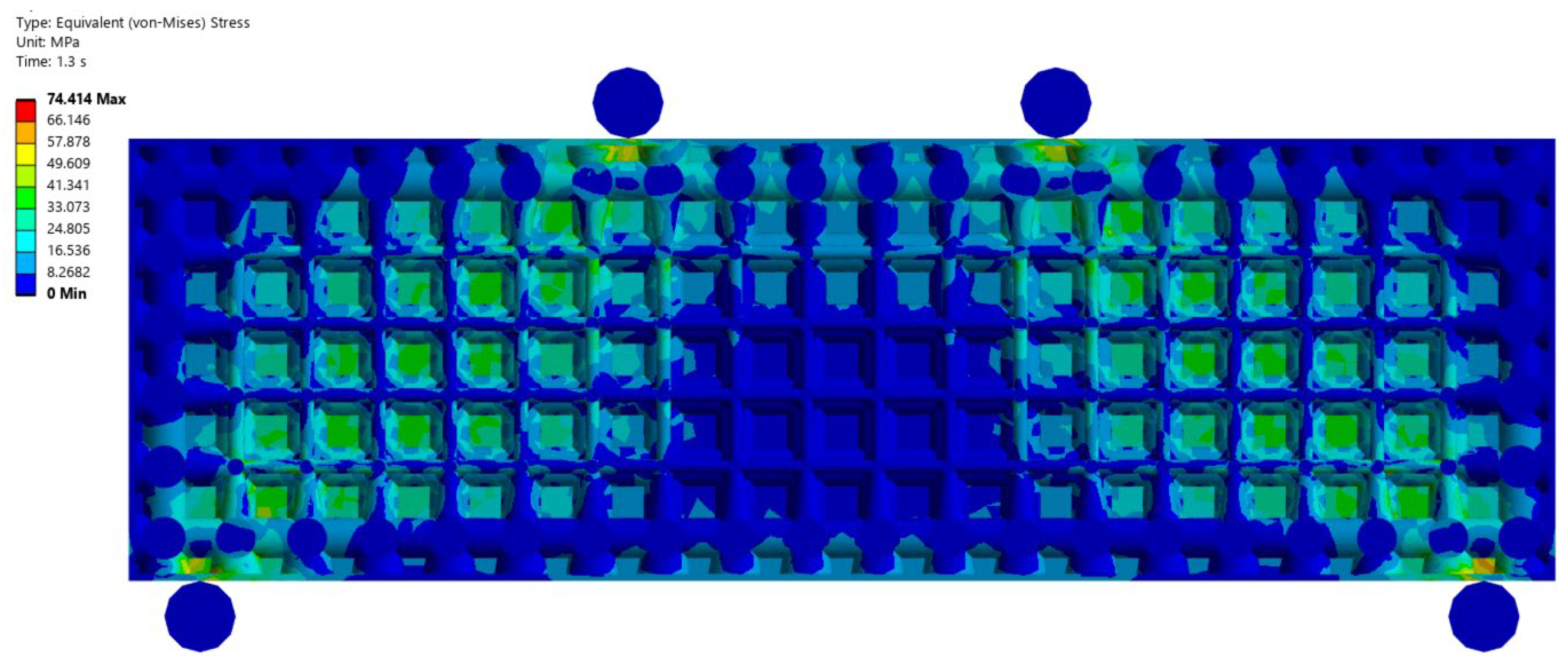

3.2. Numerical Model

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Su, A.; Al’Aref, S.J. History of 3D Printing. 3D Print. Appl. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, J.M.; Caminero, M.A.; García-Plaza, E.; Núñez, P.J. Additive Manufacturing of PLA Structures Using Fused Deposition Modelling: Effect of Process Parameters on Mechanical Properties and Their Optimal Selection. Mater. Des. 2017, 124, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizon, J.R.C.; Espera, A.H.; Chen, Q.; Advincula, R.C. Mechanical Characterization of 3D-Printed Polymers. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 20, 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Geng, P.; Li, G.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J. Influence of Layer Thickness and Raster Angle on the Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed PEEK and a Comparative Mechanical Study between PEEK and ABS. Materials 2015, 8, 5834–5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabacu, S.; Ducu, C. Numerical Investigations of 3D Printed Structures under Compressive Loads Using Damage and Fracture Criterion: Experiments, Parameter Identification, and Validation. Extreme Mech. Lett. 2020, 39, 100775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravani, M.R.; Zolfagharian, A. Fracture and Load-Carrying Capacity of 3D-Printed Cracked Components. Extreme Mech. Lett. 2020, 37, 100692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.K.; Senthil, P.; Adarsh, S.; Anoop, M.S. An Investigation to Study the Combined Effect of Different Infill Pattern and Infill Density on the Impact Strength of 3D Printed Polylactic Acid Parts. Compos. Commun. 2021, 24, 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubombo, C.; Huneault, M.A. Effect of Infill Patterns on the Mechanical Performance of Lightweight 3D-Printed Cellular PLA Parts. Mater. Today Commun. 2018, 17, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Ruban, W.; Deepanraj, A.; Bhuvanesh, R.; Bhuvanesh, T. Effect on Infill Density on Mechanical Properties of PETG Part Fabricated by Fused Deposition Modelling. In Proceedings of the Materials Today: Proceedings; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Dudescu, C.; Racz, L. Effects of Raster Orientation, Infill Rate and Infill Pattern on the Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Materials. ACTA Univ. Cibiniensis 2017, 69, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoratko, A.; Katzer, J. Harnessing 3D Printing of Plastics in Construction—Opportunities and Limitations. Materials 2021, 14, 4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzer, J.; Szatkiewicz, T. Effect of 3D Printed Spatial Reinforcement on Flexural Characteristics of Conventional Mortar. Materials 2020, 13, 3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon-Hernandez, S.; Garcia-Gonzalez, D.; Jérusalem, A.; Arias, A. Design of FDM 3D Printed Polymers: An Experimental-Modelling Methodology for the Prediction of Mechanical Properties. Mater. Des. 2020, 188, 108414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, P.; Pařenica, P.; Juračka, D.; Krejsa, M. Numerical Analysis of 3D Printed Joint of Wooden Structures Regarding Mechanical and Fatigue Behaviour. Fract. Struct. Integr. 2024, 19, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandrino, J.D.; Concepcion, R.S.; Lauguico, S.C.; Tobias, R.R.; Venancio, L.; Macasaet, D.; Bandala, A.A.; Dadios, E.P. A Machine Learning Approach of Lattice Infill Pattern for Increasing Material Efficiency in Additive Manufacturing Processes. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Robot. Res. 2020, 9, 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, W.; Pucklitzsch, T.; Dietrich, D.; Nickel, D. Mechanical Performance of Hexagonal Close-Packed Hollow Sphere Infill Structures with Shared Walls under Compression Load. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 59, 103135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kwon, C.; Yoo, J.; Min, S.; Nomura, T.; Dede, E.M. Design of Spatially-Varying Orthotropic Infill Structures Using Multiscale Topology Optimization and Explicit de-Homogenization. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 40, 101920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzer, J.; Skoratko, A. Concept of Using 3D Printing for Production of Concrete-Plastic Columns with Unconventional Cross-Sections. Materials 2021, 14, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maszybrocka, J.; Dworak, M.; Nowakowska, G.; Osak, P.; Łosiewicz, B. The Influence of the Gradient Infill of PLA Samples Produced with the FDM Technique on Their Mechanical Properties. Materials 2022, 15, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xie, D.; Gu, J.; Shen, L.; Tian, Z.; Zhao, J. Mechanical Properties and Dynamic Characterization of Gradient IWP Structures Fabricated by Additive Manufacturing. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 42, 111154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusa i3 Original Prusa I3 MK3S+ 3D Printer. Available online: https://help.prusa3d.com/cs/product/mk3s-2/o-vasi-tiskarne_201 (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- ANSYS. ANSYS Meshing User’s Guide. Available online: https://customercenter.ansys.com/ (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Juracka, D.; Kawulok, M.; Bujdos, D.; Krejsa, M. Influence of Size and Orientation of 3D Printed Fiber on Mechanical Properties under Bending Stress. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 2022, 66, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juračka, D.; Bujdoš, D.; Lehner, P. Numerical and Experimental Analysis of Mechanical and Fatigue Properties of Special Shaped 3D Printed Sample. Fract. Struct. Integr. 2025, 19, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Sample | Weight (g) | Printing Time (Hours) |

|---|---|---|

| Structured | 267 | 33.16 |

| Solid | 634 | 20.16 |

| Parameter | PC Blend |

|---|---|

| Density [kg·m3] | 1220 |

| Modulus of elasticity [GPa] | 1.90 |

| Poisson ratio [-] | 0.35 |

| Tensile strength [MPa] | 63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juracka, D.; Lehner, P.; Kawulok, M.; Bujdos, D.; Krejsa, M. 3D Printed Beam with Optimized Internal Structure—Experimental and Numerical Approach. Materials 2025, 18, 5512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245512

Juracka D, Lehner P, Kawulok M, Bujdos D, Krejsa M. 3D Printed Beam with Optimized Internal Structure—Experimental and Numerical Approach. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245512

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuracka, David, Petr Lehner, Marek Kawulok, David Bujdos, and Martin Krejsa. 2025. "3D Printed Beam with Optimized Internal Structure—Experimental and Numerical Approach" Materials 18, no. 24: 5512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245512

APA StyleJuracka, D., Lehner, P., Kawulok, M., Bujdos, D., & Krejsa, M. (2025). 3D Printed Beam with Optimized Internal Structure—Experimental and Numerical Approach. Materials, 18(24), 5512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245512