Basalt-Based Composite with Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO)—Preliminary Study on Anti-Cut Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Basalt Fibers

1.2. Properties of Graphene–rGO—Strength, Stiffness, and Chemical Resistance

1.3. Research Examples of Comparable Composites

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Tested

2.2. Cut Resistance Evaluation Methods

2.3. Composite Preparation: Vacuum-Assisted Resin Infusion with Graphene-Modified Epoxy System

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Composite Preparation

3.2. Cut Resistance Evaluation

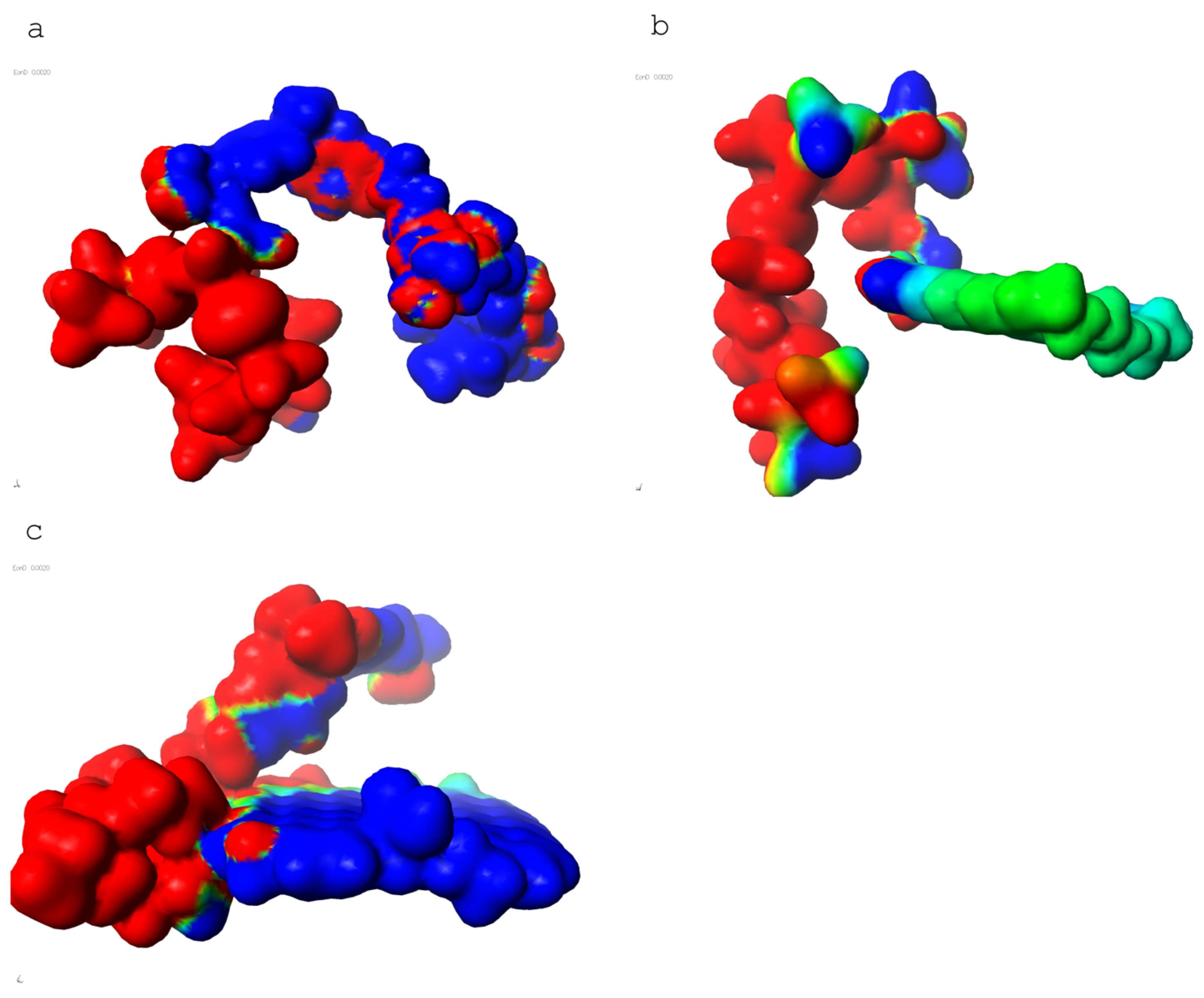

3.3. Molecular Simulations

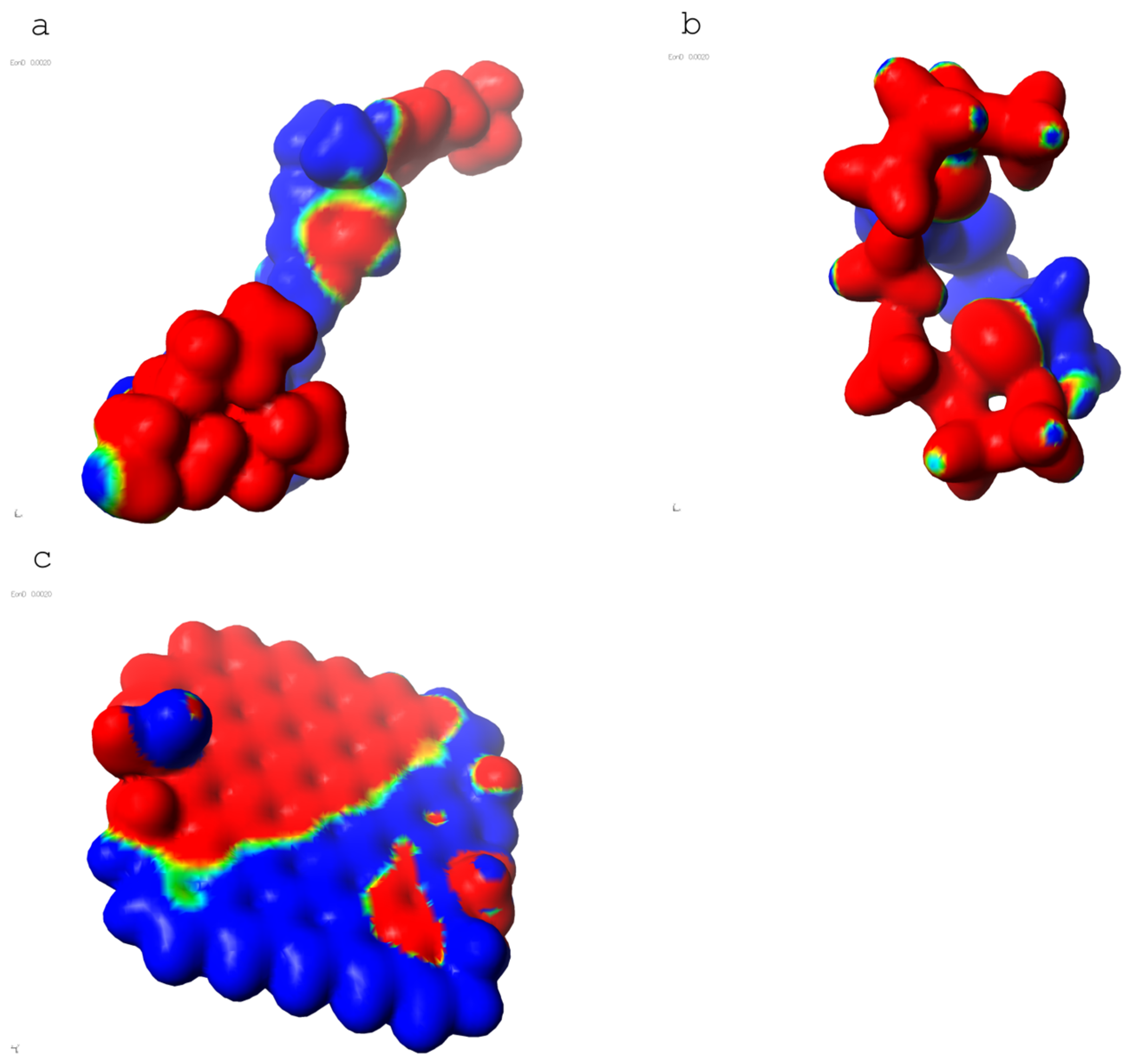

3.3.1. Stage 1—Modeling of Pure Components

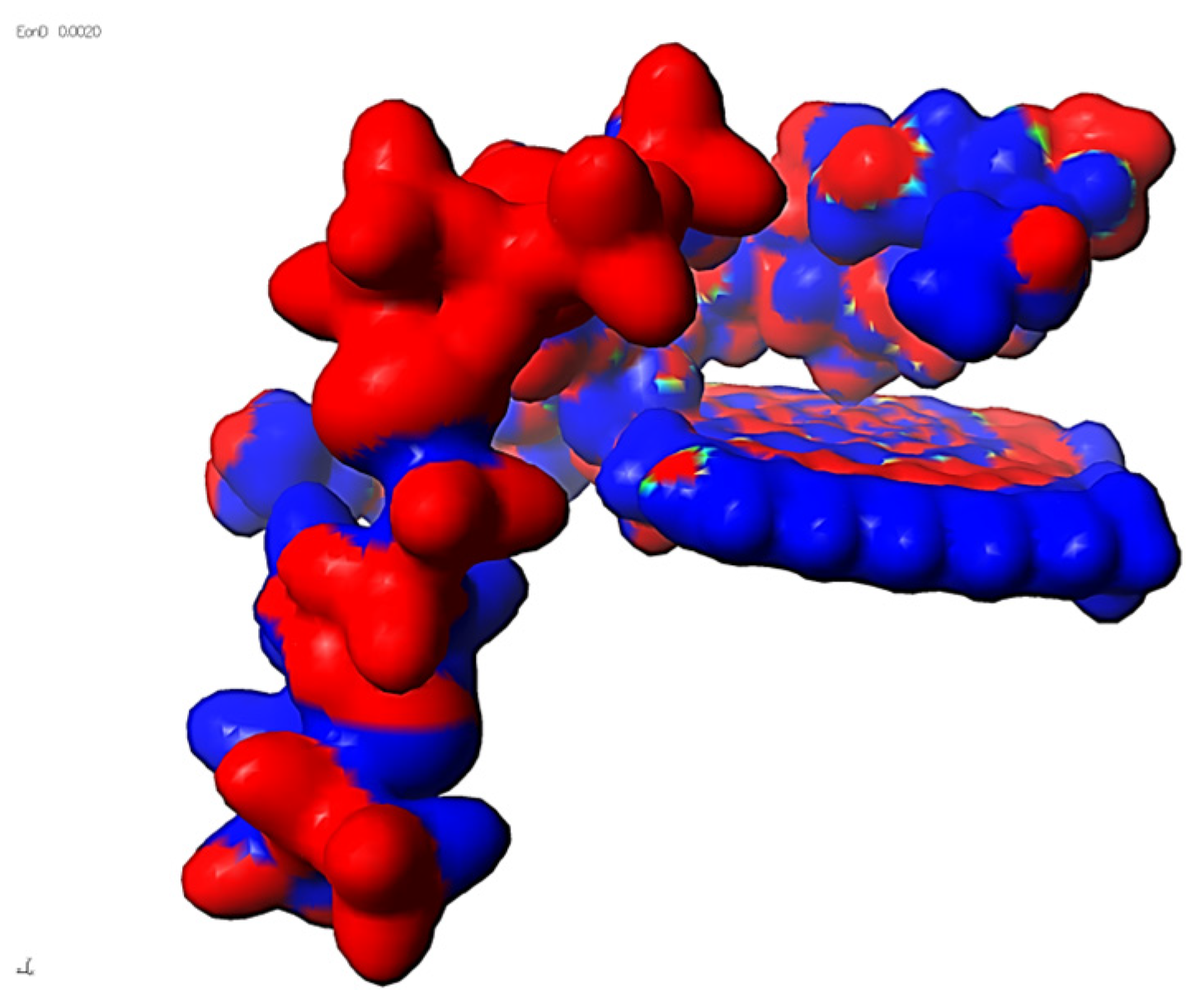

3.3.2. Stage 2—Pairwise Interactions

3.3.3. Stage 3—Ternary System Modeling

3.4. Summary

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Irzmańska, E.; Mizera, K.; Litwicka, N.; Sałasińska, K. An Approach to Testing Anti-vandal Composite Materials as a Function of Their Thickness and Striker Shape—A Case Study. Polymers 2024, 16, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irzmańska, E.; Mizera, K.; Sałasińska, K. Validation procedures for assessing the properties of anti-vandal materials for applications in public transport vehicles. Polimery 2024, 69, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilewicz, P.; Cichocka, A.; Frydrych, I. Underwear for Protective Clothing Used by Foundry Workers. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2016, 24, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydrych, I.; Cichocka, A.; Adamczyk, P.; Dominiak, J. Comparative Analysis of the Thermal Insulation of Traditional and Newly Designed Protective Clothing for Foundry Workers. Polymers 2016, 8, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miśkiewicz, P.; Frydrych, I.; Pawlak, W.; Cichocka, A. Modification of Surface of Basalt Fabric on Protecting Against High Temperatures by the Method of Magnetron Sputtering. Autex Res. J. 2019, 19, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydrych, I. Towaroznawstwo odzieżowe—Surowce na ubrania ochronne Część I: Ubrania chroniące przed ogniem. Przegląd Włókienniczy-Włókno Odzież Skóra 2008, 6, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Savanan, D. Spinning the Rock—Basalt Fibers. J. TX 2006, 86, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Militký, J.; Kovačič, V.; Bajzík, V. Mechanical Properties of Basalt Filaments. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2007, 15, 64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Witek, J.; Łukwiński, L.; Wasilewski, R. Ocena Własności Fizyko-Chemicznych Odpadów Zawierających Nieorganiczne Włókna Sztuczne. Available online: https://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-article-BPP1-0035-0061 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Van de Velde, K.; Kiekens, P.; Van Langenhove, L. Basalt Fibres as Reinforcement for Composites. Available online: https://www.basaltex.com/products/woven-fabrics (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Lisakovski, A.N.; Tsybulya, Y.L.; Me/dvedyev, A.A. Yarns of basalt continuous fibers—Part I. Rev. Text. 2003, 10, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ćerný, M.; Glogar, P.; Goliáš, V.; Hruška, J.; Jakeš, P.; Sucharda, Z.; Vávrová, I. Comparison of mechanical properties and structural changes of continuous basalt and glass fibres at elevated temperatures. Ceram.-Silikáty 2007, 51, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V.; Firsov, A.A. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitby, R.L.D. Chemical Control of Graphene Architecture: Tailoring Shape and Properties. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 9733–9754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balandin, A.A.; Ghosh, S.; Bao, W.; Calizo, I.; Teweldebrhan, D.; Miao, F.; Lau, C.N. Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 902–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelin, C.-E.; Pelin, G. Mechanical properties of basalt fiber/epoxy resin composites. INCAS Bull. 2024, 16, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepetcioglu, H.; Lapčík, L.; Lapčíková, B.; Vašina, M.; Hui, D.; Ovsík, M.; Staněk, M.; Murtaja, Y.; Kvítek, L.; Lapčíková, T.; et al. Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2024, 13, 20240052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolhasani, M.M.; Azimi, S.; Mousavi, M.; Anwar, S.; Amiri, M.H.; Shirvanimoghaddam, K.; Naebe, M.; Michels, J.; Asadi, K. Porous graphene/poly(vinylidene fluoride) nanofibers for pressure sensing. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, e52040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, Y.; Muramatsu, K.; Sumi, H.; Nishioka, Y. Graphene-coated carbon fiber cloth for flexible electrodes of glucose fuel cells. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 55, 02BE05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Qi, P.; Ding, X.; Zhang, H. Graphene composite coated carbon fiber: Electrochemical synthesis and application in electrochemical sensing. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 11250–11255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabedini, A.; Ang, A.; Nikzad, M.; Fox, B.; Lau, K.; Hameed, N. Evolving strategies for producing multiscale graphene-enhanced fiber-reinforced polymer composites for smart structural applications. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1903501. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Song, D.; Jiang, J.; Li, W.; Huang, H.; Yu, Z.; Peng, Z.; Zhu, X.; Wang, F.; Lan, H. Electrically assisted continuous vat photopolymerization 3D printing for fabricating high-performance ordered graphene/polymer composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 250, 110449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Ali, M.A.; Khan, T.; Anwer, S.; Liao, K.; Umer, R. MXene and graphene coated multifunctional fiber reinforced aerospace composites with sensing and EMI shielding abilities. Compos. Part A 2023, 165, 107351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3822; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Single Textile Fibers. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D2101; Test Method for Tensile Properties of Single Man-Made Textile Fibers Taken From Yarns and Tows. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1994.

- Militký, J.; Kovačič, V.; Rubnerova, J. Influence of thermal treatment on tensile failure of basalt fibers. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2002, 69, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1082-3:2000; Protective Clothing—Gloves and Arm Guards Protecting Against Cuts and Stabs by Hand Knives—Part 3: Impact Cut Test for Fabric, Leather and Other Materials. iTeh, Inc.: Newark, DE, USA, 2000.

- EN ISO 13998:2003; Protective Clothing. Aprons, Trousers and Vests Protecting Against Cuts and Stabs by Hand Knives. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- EN ISO 13997:2023; (TDM Test) Protective Clothing. Mechanical Properties. Determi-Nation of Resistance to Cutting by Sharp Objects. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- Kaczmarek, Ł.; Balik, M.; Warga, T.; Acznik, I.; Lota, K.; Miszczak, S.; Sobczyk-Guzenda, A.; Kyzioł, K.; Zawadzki, P.; Wosiak, A. Functionalization Mechanism of Reduced Graphene Oxide Flakes with BF3·THF and Its Influence on Interaction with Li+ Ions in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Materials 2021, 14, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opuchlik, N. The Influence of Hydrogen on Selected Mechanical Properties of Polymer Composites with Graphene Addition. Master’s Thesis, Institute of Materials Science and Engineering Lodz Unveristy of Technology, Lodz, Poland, 2025. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Roślak, A. Analysis of Strength Characteristics of Epoxy Resins with a Graphene Powder. Master’s Thesis, Institute of Materials Science and Engineering, Lodz University of Technology, Lodz, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Basalt Fiber | Glass Fiber (Type E) |

|---|---|---|

| Fiber diameter, µm | 7–22 | 5–20 |

| Density, g/cm3 | 2.65 | 2.60 |

| Tensile strength, MPa | 4150–4800 | 3450 |

| Young’s modulus, GPa | 100–110 | 76 |

| Elongation at break, % | 3.30 | 4.76 |

| Operating temperature range, °C | −260 to +700 | −60 to +380 |

| Short-term maximum heat resistance, °C | +750 | +550 |

| Melting point, °C | +1050 to +1460 | +730 to +1000 |

| Thermal insulation (conductivity), W/m2·K | 0.031–0.038 | 0.034–0.040 |

| No. | Fabric Description | Areal Density (g/m2) | Thickness (mm) | Weave | Thread Density (Threads/dm) Warp g0/ Weft gt | Warp Yarn Type | Weft Yarn Type | Other External Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fabric made of 100% basalt fiber yarn  | 805 | 0.91 | Warp-faced twill 3/1 S | g0 = 40/ gt = 40 | Continuous filament yarn | Continuous filament yarn | Good drapability. Pronounced surface texture. Visible gaps in the structure. Lower yarn slippage in both warp and weft directions. |

| 2 | Fabric made of 100% basalt fiber yarn  | 385 | 0.49 | Plain | g0 = 30/ gt = 30 | Continuous filament yarn | Continuous filament yarn | Good drapability. Pronounced surface texture. Visible gaps in the structure. High yarn slippage In both warp and weft directions. |

| 3 | Fabric made of 100% basalt fiber yarn  | 286 | 0.31 | Plain | g0 = 100 gt = 100 | Continuous filament yarn | Continuous filament yarn | Dense fabric structure, low flexibility. Some yarn slippage in both warp and weft directions. |

| 4 | Fabric made of 100% aluminized basalt fiber yarn   | 228 | 0.29 | Plain | g0 = 100/ gt = 80 | Continuous filament yarn | Continuous filament yarn | Good drapability. Distinct surface texture. No visible gaps in the structure. No yarn slippage in either warp or weft directions. |

| Mechanical Parameter | Basalt Fiber | E-Glass Fiber |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength [24] [mN/tex] | 600–730 | 350–500 |

| Stress [25] [MPa] | 4000–4300 | 3450–3800 |

| Tensile Modulus [25] [GPa] | 84–87 | 72–76 |

| No. | Component [%] | E-Glass Fibers | S-Glass Fibers | C-Glass Fibers | Basalt Fibers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SiO2 | 52–56 | 65 | 64–68 | 51.56 |

| 2 | Al2O3 | 12–16 | 25 | 3–5 | 18.24 |

| 3 | CaO | 16–25 | – | 11–15 | 5.15 |

| 4 | MgO | 0–5 | 10 | 2–4 | 1.30 |

| 5 | B2O3 | 5–10 | – | 4–6 | – |

| 6 | Na2O | 0.8 | 0.3 | 7–10 | 6.36 |

| 7 | K2O | – | – | – | 4.50 |

| 8 | TiO2 | – | – | – | 1.23 |

| 9 | Fe2O3 | – | – | – | 4.02 |

| 10 | FeO | – | – | – | 2.14 |

| 11 | MnO | – | – | – | 0.28 |

| 12 | H2O | – | – | – | 0.46 |

| 13 | P2O5 | – | – | – | 0.26 |

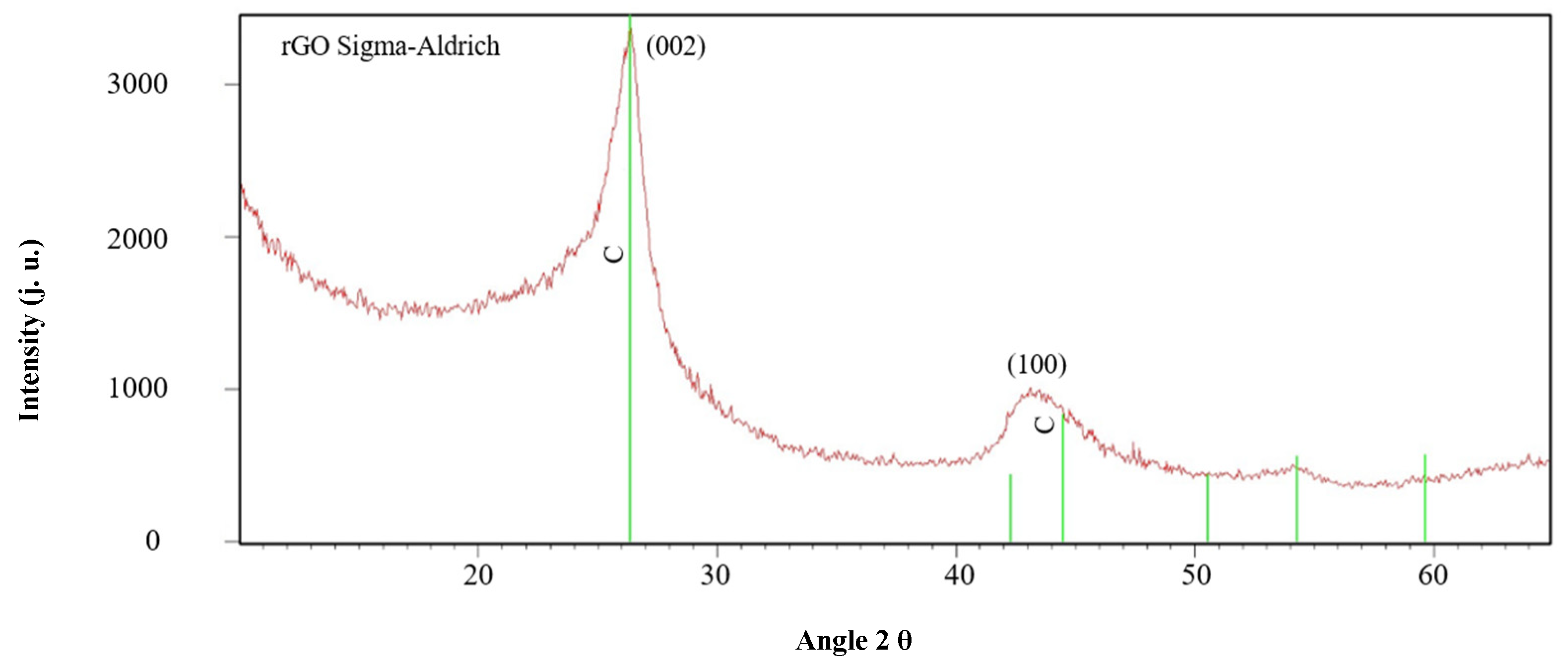

| 2θ [°] | β [°] | H [nm] | d002 [nm] | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25.91 | 3.04 | 2.8 | 0.343 | ~8 |

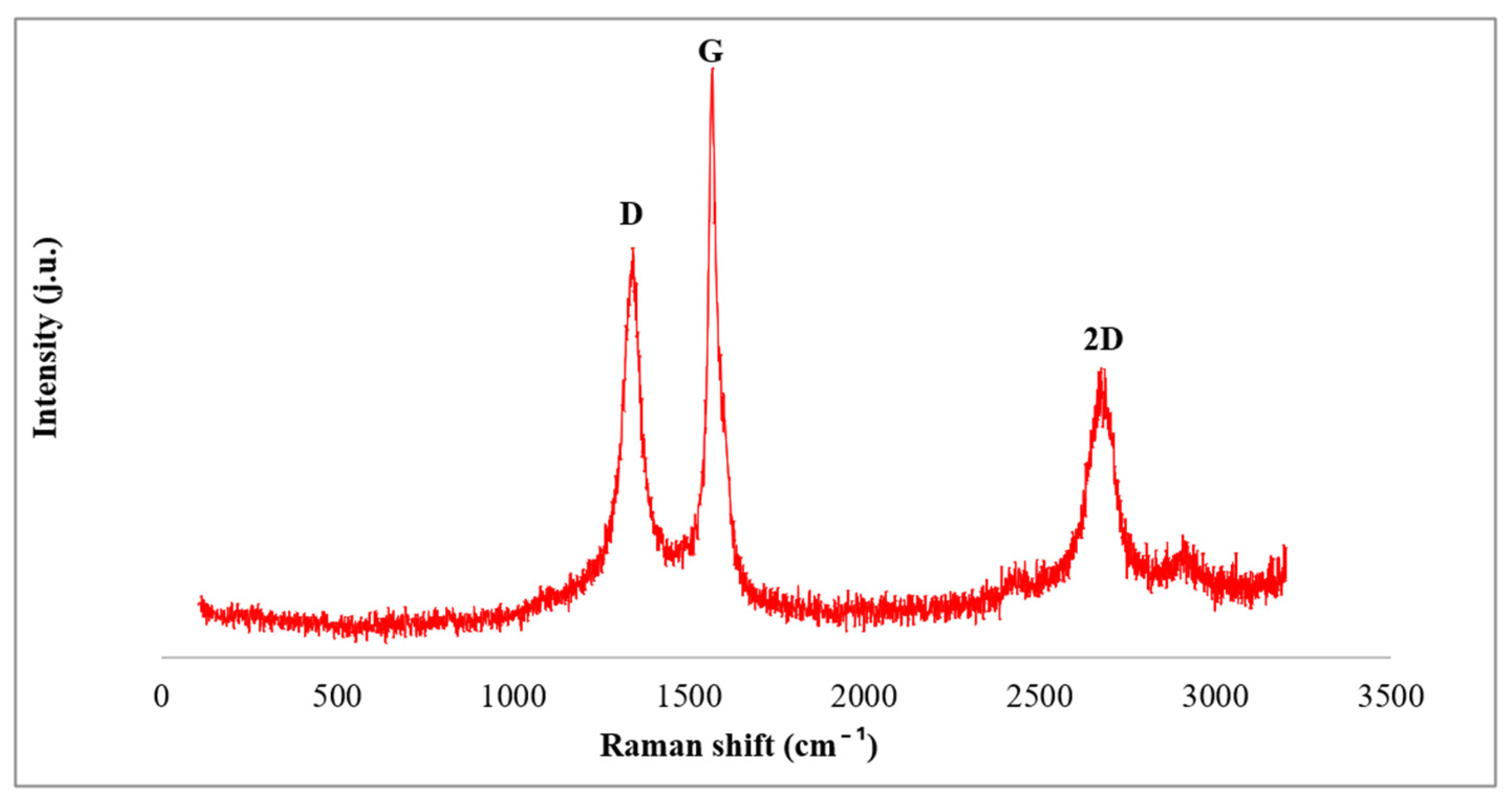

| Intensity (j. u.) | Shift (cm−1) | Intensity Ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | IG | I2D | D | G | 2D | ID/IG | I2D/IG |

| 940.2 | 1412.2 | 549.9 | 1339 | 1567.4 | 2677.2 | 0.67 | 0.39 |

| No. | Structure of the Sample Presented via Optical Microscope OPTAtech, 10× Magnification | Knife Impact Resistance According to EN ISO 13998:2003 (Blade Impact Energy: 2.45 J) | Cut Resistance Against Sharp Objects According to EN ISO 13997:2023 (All Samples Tested with 150 N Force) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | >55 mm | 0 mm No visible point of cut |

| 2 |  | >55 mm | 0 mm |

| 3 |  | >55 mm No visible point of cut | 0 mm No visible point of cut |

| 4 |  | >55 mm | 0 mm |

| No. | Structure of the Sample Presented via Optical Microscope OPTAtech, 10× Magnification | Cut Resistance from Blade Impact According to EN 1082-3:2000 (Blade Impact Energy: 2.45 J) | Cut Resistance to Sharp Objects According to EN ISO 13997:2023 (All Samples Tested with 150 N Force) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | 19 mm | The sample was too small and stiff to allow measurement using the TDM device. |

| 2 |  | 41.5 mm | 56.4 mm |

| 3 |  | >55 mm | 60.6 mm |

| 4 |  | 32.5 mm | 59.7 mm |

| Molecular System | System Energy Value (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| Cross-linked LG 700 resin | −393 |

| rGO | +225 |

| Basalt | −4279 |

| Cross-linked LG 700 resin–rGO | −178 |

| Basalt–rGO | −4055 |

| Cross-linked LG 700 resin–basalt | −4677 |

| Cross-linked LG 700 resin–rGO–basalt | −4439 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cichocka, A.; Frydrych, I.; Zawadzki, P.; Kaczmarek, Ł.; Irzmańska, E.; Kropidłowska, P. Basalt-Based Composite with Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO)—Preliminary Study on Anti-Cut Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 5513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245513

Cichocka A, Frydrych I, Zawadzki P, Kaczmarek Ł, Irzmańska E, Kropidłowska P. Basalt-Based Composite with Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO)—Preliminary Study on Anti-Cut Properties. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245513

Chicago/Turabian StyleCichocka, Agnieszka, Iwona Frydrych, Piotr Zawadzki, Łukasz Kaczmarek, Emilia Irzmańska, and Paulina Kropidłowska. 2025. "Basalt-Based Composite with Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO)—Preliminary Study on Anti-Cut Properties" Materials 18, no. 24: 5513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245513

APA StyleCichocka, A., Frydrych, I., Zawadzki, P., Kaczmarek, Ł., Irzmańska, E., & Kropidłowska, P. (2025). Basalt-Based Composite with Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO)—Preliminary Study on Anti-Cut Properties. Materials, 18(24), 5513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245513