Evaluation of Mechanical Anisotropy of New Polycarbonate Through Process Parameter Optimization in Material Extrusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Material

2.2. MEX Process

2.3. Physical Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

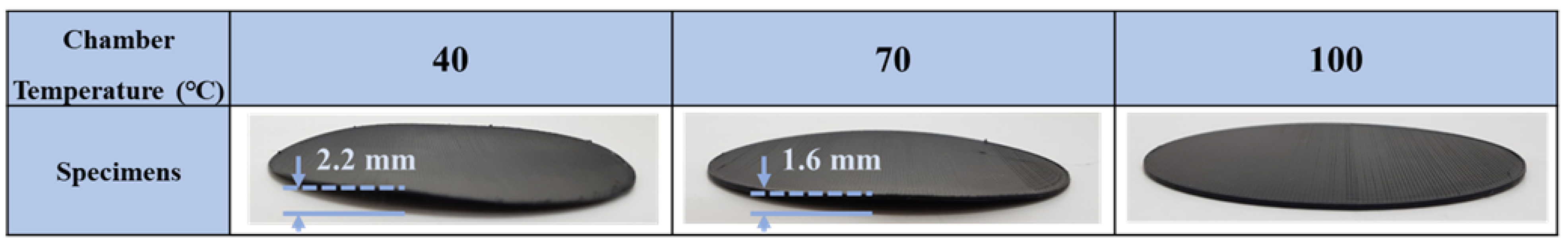

3.1. Comparison of Shrinkage According to the Chamber Temperature

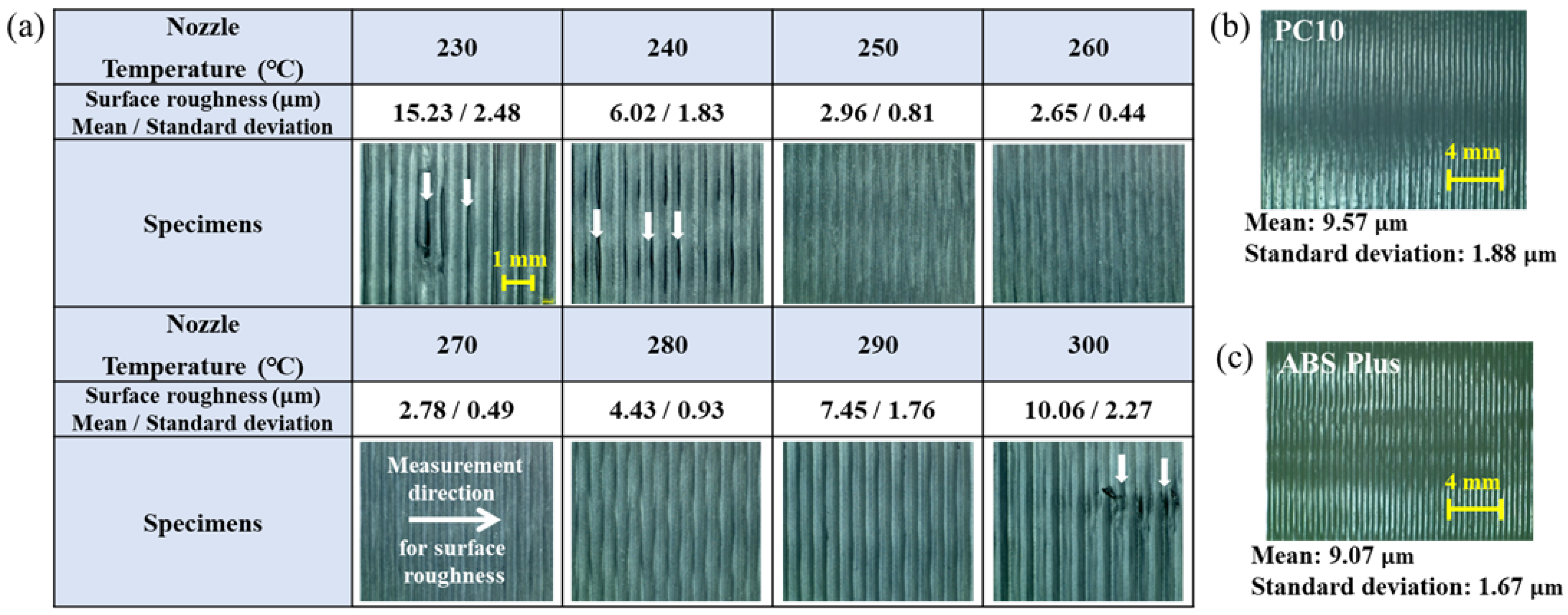

3.2. Comparison of Surface Roughness According to the Nozzle Temperature

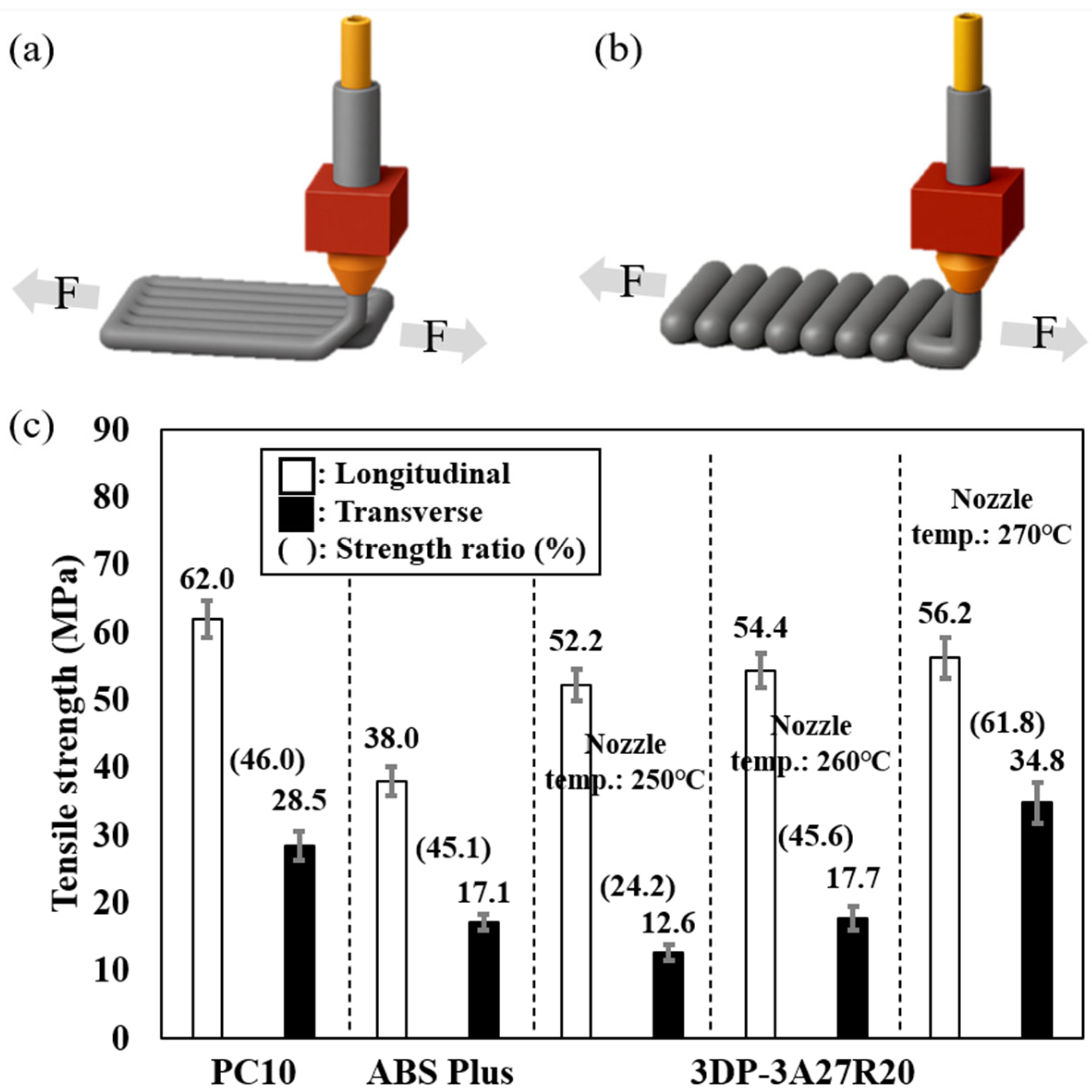

3.3. Comparison of Tensile Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yeshiwas, T.A.; Tiruneh, A.B.; Sisay, M.A. A review article on the assessment of additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Eng. 2025, 20, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ramanujan, D.; Ramani, K.; Chen, Y.; Williams, C.B.; Wang, C.C.L.; Shin, Y.C.; Zhang, S.; Zavattieri, P.D. The status, challenges, and future of additive manufacturing in engineering. Comput.-Aided Des. 2015, 69, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parupelli, S.; Desai, S. A Comprehensive Review of Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing): Processes, Applications and Future Potential. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2019, 16, 244–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Lee, J.H.; Yang, J.; Heogh, W.; Kang, D.; Yeon, S.M.; Kim, S.H.; Hong, S.; Son, Y.; Park, J. Lightweight injection mold using additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V lattice structures. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 79, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanpreecha, C.; Manonukul, A. A Review on Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing of Metal and How It Compares with Metal Injection Moulding. Metals 2022, 12, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleff, A.; Küster, B.; Stonis, M.; Overmeyer, L. Process monitoring for material extrusion additive manufacturing: A state-of-the-art review. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 6, 705–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambiase, F.; Pace, F.; Andreucci, E.; Paoletti, A. In-plane transverse mechanical properties in material extrusion components: Critical evaluation of sample preparation methodologies. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 5719–5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, C.Y.; Tolbert, J.W.; Chow, L.W.; Guvendiren, M. Interlayer bonding strength of 3D printed PEEK specimens. Soft Matter 2021, 17, 4775–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, T.; Almeida, J.H.S., Jr.; Falzon, B.G.; Kazancı, Z. Tension and Compression Properties of 3D-Printed Composites: Print Orientation and Strain Rate Effects. Polymers 2023, 15, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-López, F.; Pavón, M.M.L.; Correa, E.C.; Molina, M.H. Effects of Nozzle Temperature on Mechanical Properties of Polylactic Acid Specimens Fabricated by Fused Deposition Modeling. Polymers 2024, 16, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, F.; Cong, W.; Qiu, J.; Wei, J.; Wang, S. Additive manufacturing of carbon fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites using fused deposition modeling. Compos. Part B Eng. 2015, 80, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tymrak, B.M.; Kreiger, M.; Pearce, J.M. Mechanical properties of components fabricated with open-source 3-D printers under realistic environmental conditions. Mater. Des. 2014, 58, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, V.; Babu, K.; Kannan, G.; Mensah, R.A.; Samantaray, S.K.; Das, O. The thermal properties of FDM printed polymeric materials: A review. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 228, 110902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, J.-R.; Vogt, B.D. Size and print path effects on mechanical properties of material extrusion 3D printed plastics. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 7, 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Lee, J.E.; Park, J.; Lee, N.-K.; Son, Y.; Park, S.-H. High-temperature 3D printing of polyetheretherketone products: Perspective on industrial manufacturing applications of super engineering plastics. Mater. Des. 2021, 211, 110163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Runzi, M.; Wang, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y. Influence of Filament Moisture on 3D Printing Nylon. Technologies 2025, 13, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šafář, M.; Dütsch, L.; Harničárová, M.; Valíček, J.; Kušnerová, M.; Tozan, H.; Kopal, I.; Falta, K.; Borzan, C.; Palková, Z. Comprehensive Prediction Model for Analysis of Rolling Bearing Ring Waviness. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, E.B.; Di Nisio, F.G.; Cano, F.C.; Voltolini, R.; Volpato, N. A study about weak intralayer bonding in extrusion-based additive manufacturing due to resumed extrusion during filling. Polym. Test. 2024, 140, 108595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlon, S.; Le Boterff, J.; Soulestin, J. Fused filament fabrication of polypropylene: Influence of the bead temperature on adhesion and porosity. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 38, 101838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukindar, N.A.; Yasir, A.S.H.M.; Azhar, M.D.; Azhar, M.A.M.; Halim, N.F.H.A.; Sulaiman, M.H.; Sabli, A.S.H.A.; Ariffin, M.K.A.M. Evaluation of the surface roughness and dimensional accuracy of low-cost 3D-printed parts made of PLA–aluminum. Heliyon 2024, 10, 25508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahar, A.; Belhabib, S.; Guessasma, S.; Benmahiddine, F.; Hamami, A.E.A.; Belarbi, R. Mechanical and Thermal Properties of 3D Printed Polycarbonate. Energies 2022, 15, 3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, P.; Bazan, A.; Bulicz, M. Effect of 3D Printing Orientation on the Accuracy and Surface Roughness of Polycarbonate Samples. Machines 2024, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, H.B.; Park, J.; Lee, N.-K.; Son, Y.; Park, S.-H. 3D printing of bio-based polycarbonate and its potential applications in ecofriendly indoor manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 31, 100974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohdi, N.; Yang, R. Material Anisotropy in Additively Manufactured Polymers and Polymer Composites: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.E.; Son, Y.; Park, S.J. Evaluation of Mechanical Anisotropy of New Polycarbonate Through Process Parameter Optimization in Material Extrusion. Materials 2025, 18, 5511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245511

Han J, Kim S, Lee JE, Son Y, Park SJ. Evaluation of Mechanical Anisotropy of New Polycarbonate Through Process Parameter Optimization in Material Extrusion. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245511

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Jaemin, Seongjun Kim, Ji Eun Lee, Yong Son, and Seong Je Park. 2025. "Evaluation of Mechanical Anisotropy of New Polycarbonate Through Process Parameter Optimization in Material Extrusion" Materials 18, no. 24: 5511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245511

APA StyleHan, J., Kim, S., Lee, J. E., Son, Y., & Park, S. J. (2025). Evaluation of Mechanical Anisotropy of New Polycarbonate Through Process Parameter Optimization in Material Extrusion. Materials, 18(24), 5511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245511