Macroscopic and Microscopic Performance Study of Filling-Type Large-Size Cement-Stabilized Macadam

Highlights

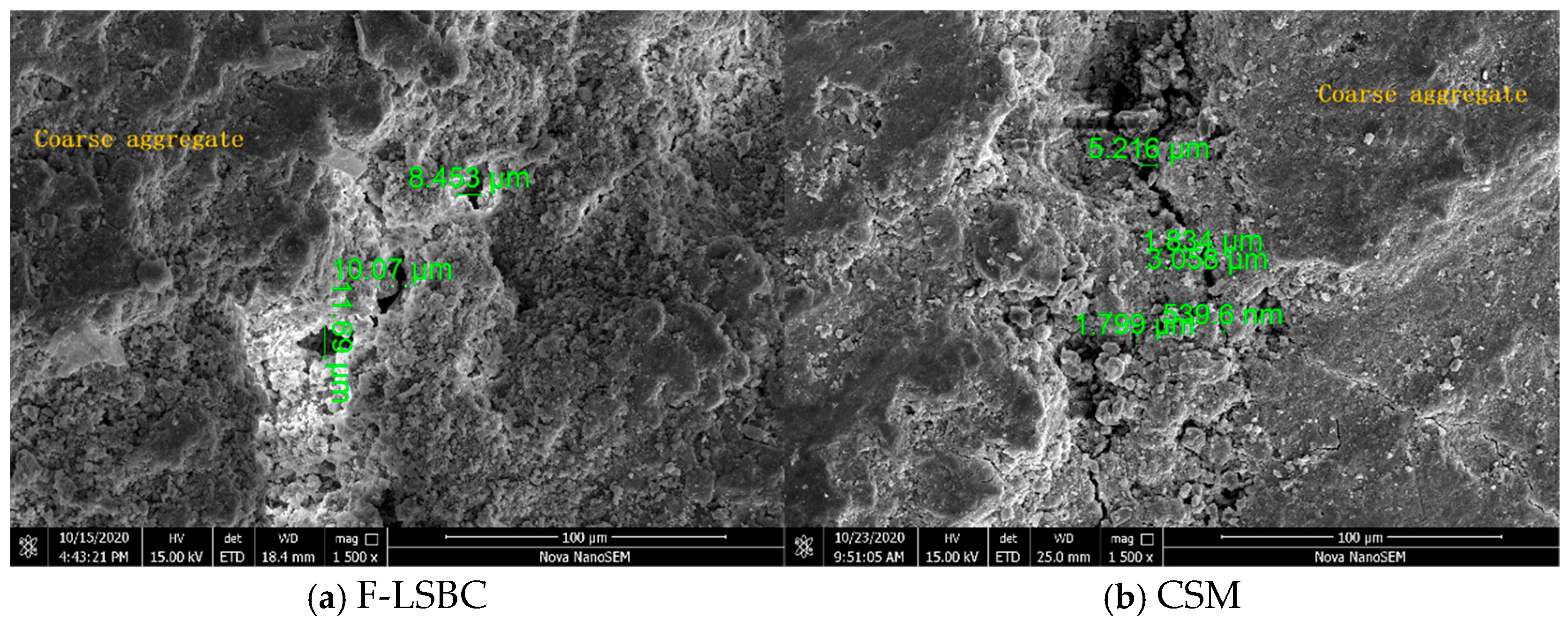

- F-LSBC exhibits 60–75% ITZ modulus and 55% hardness compared to conventional CSM.

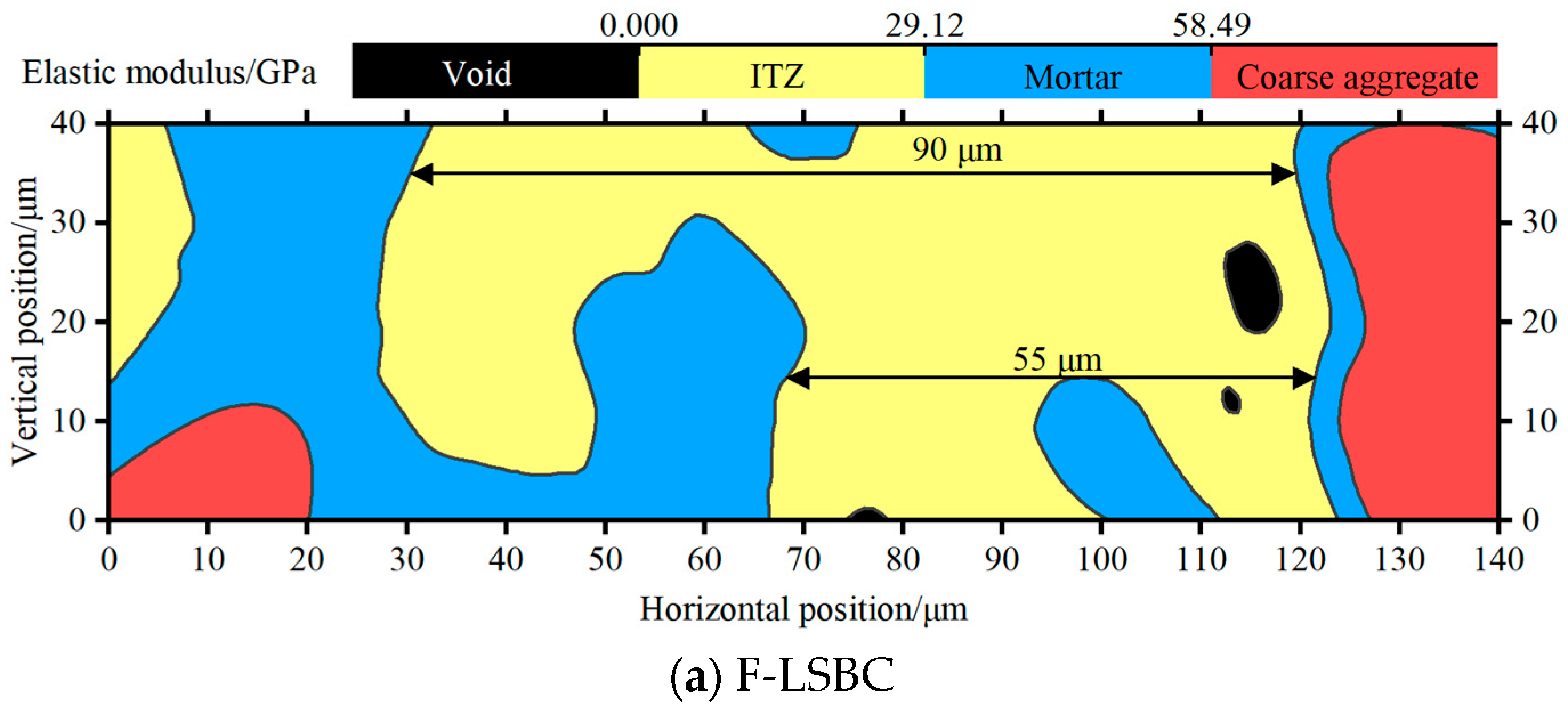

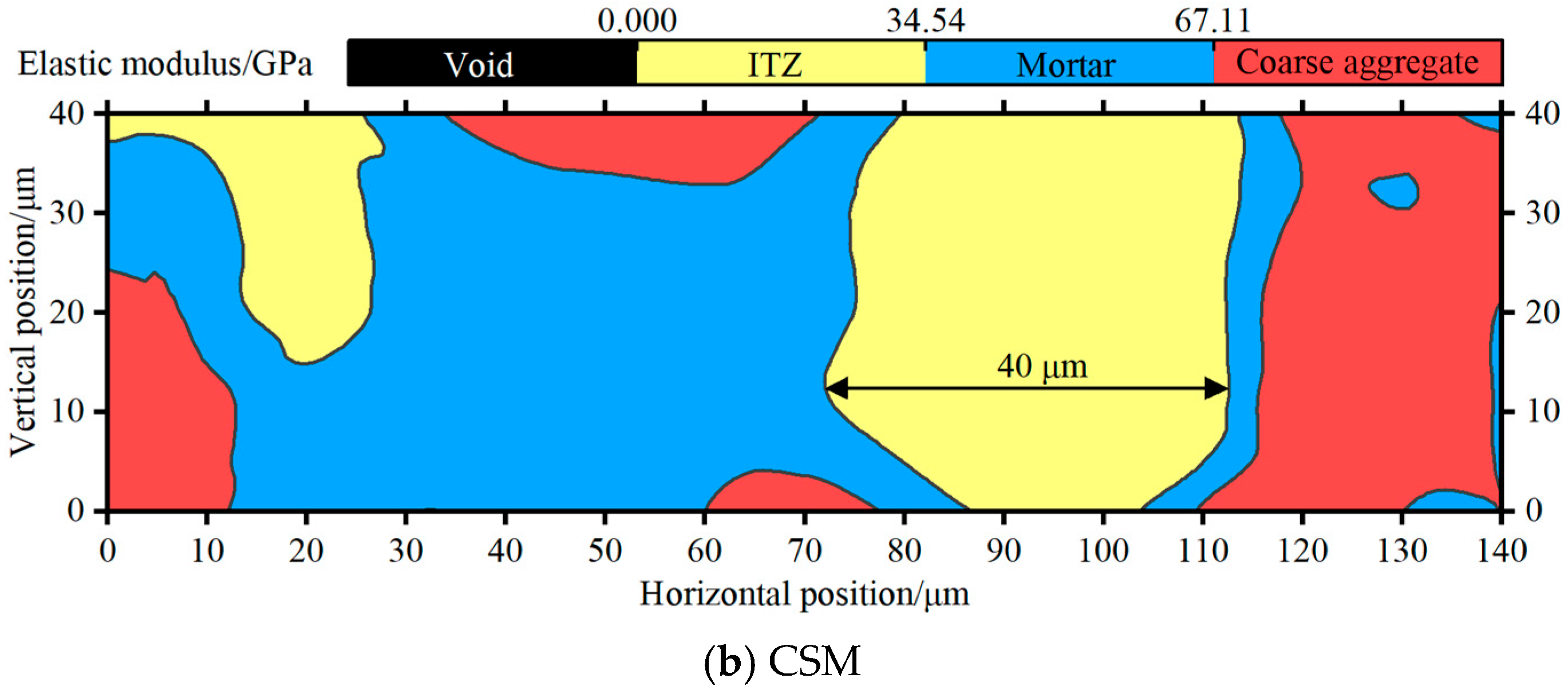

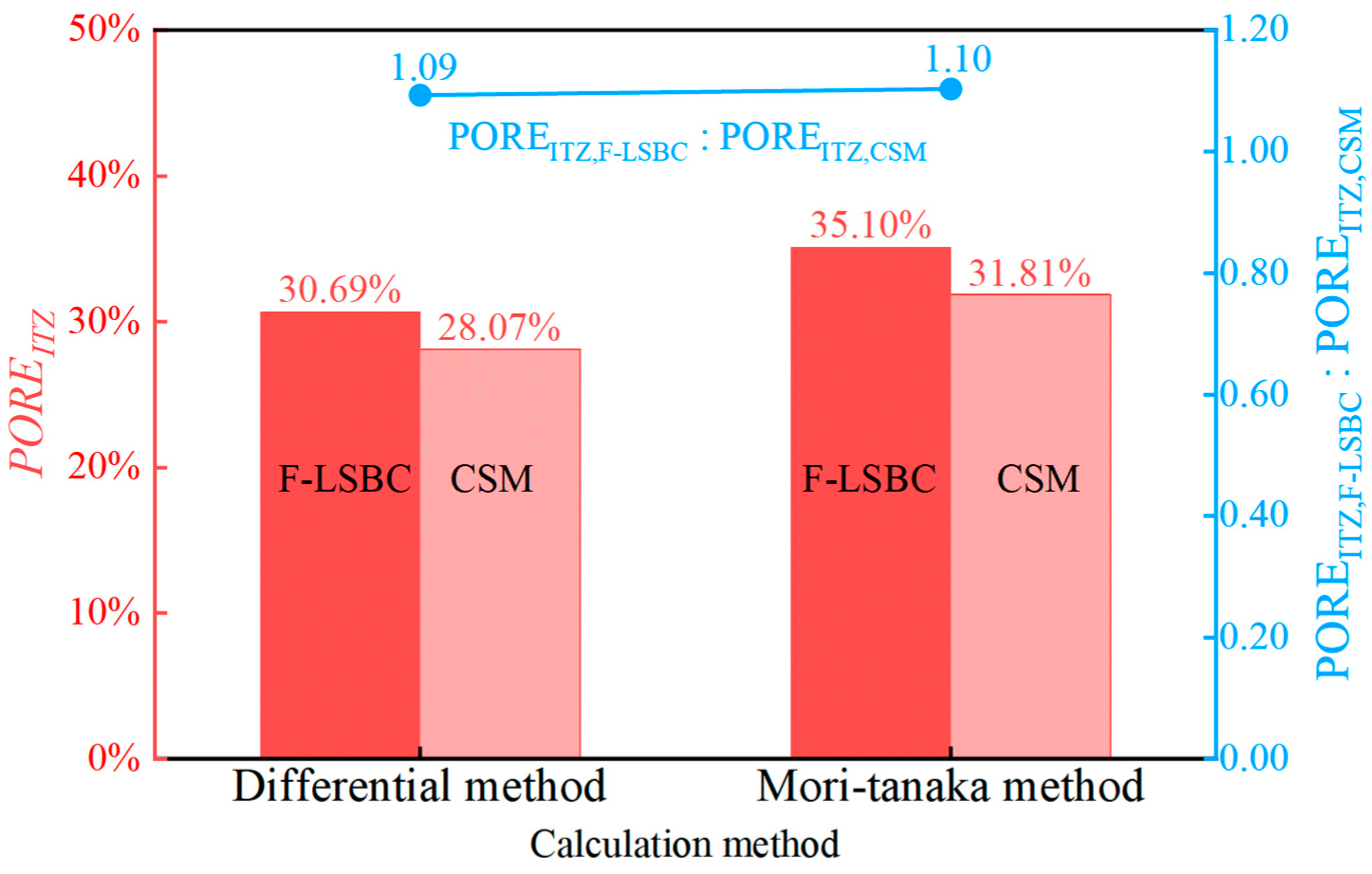

- The ITZ of F-LSBC is thicker (55–90 μm) and 1.5× larger in volume fraction than in CSM.

- F-LSBC shows lower strength and fatigue life due to pronounced interfacial weakening.

- High coarse aggregate content and weak interface reduce overall shrinkage deformation.

- Nanoindentation–macro testing links ITZ microstructure to macroscopic performance.

- Interface engineering is key to balancing strength and crack resistance in F-LSBC bases.

- Weak ITZ design provides “crack-without-displacement” behavior for shrinkage control.

- Enhancing ITZ compactness can improve both mechanical durability and fatigue resistance.

- Results guide optimization of semi-rigid base materials for reflection crack mitigation.

- Findings support durable, low-shrinkage cement-stabilized base design for pavements.

Abstract

1. Introduction

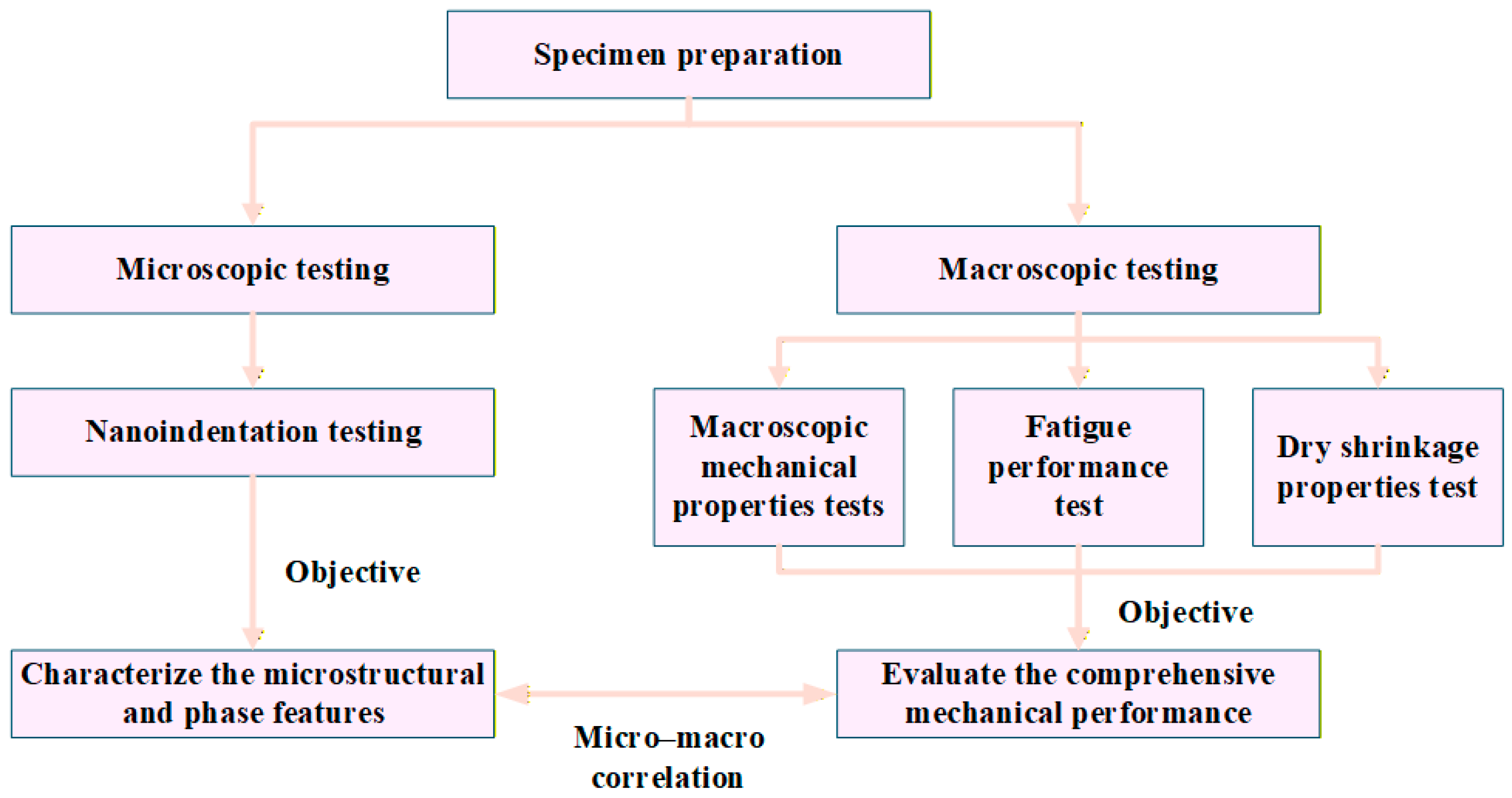

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Preparation

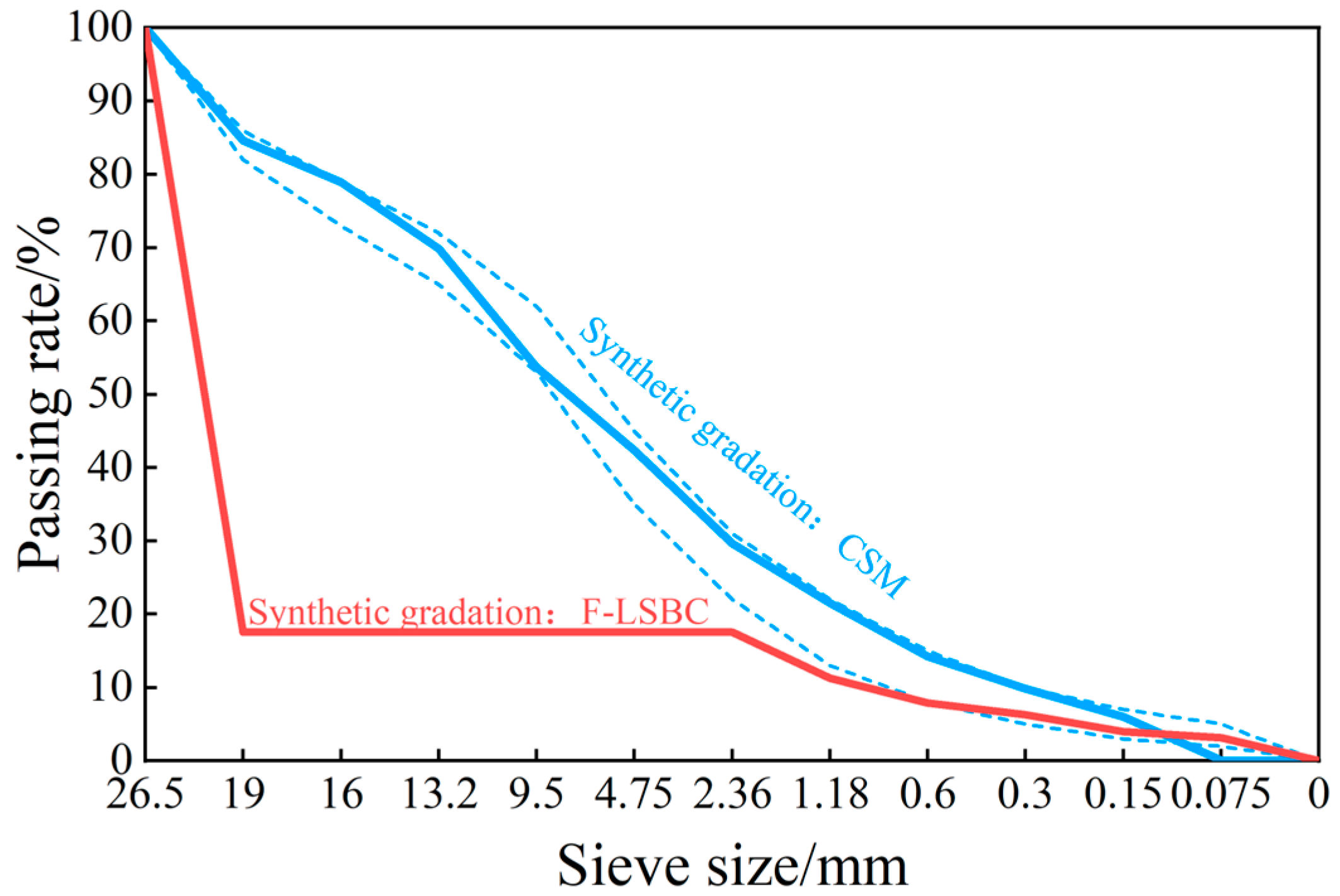

2.1.1. Synthetic Gradation

2.1.2. Physical Parameters

2.1.3. Specimen Preparation and Curing

2.2. Microscopic Testing

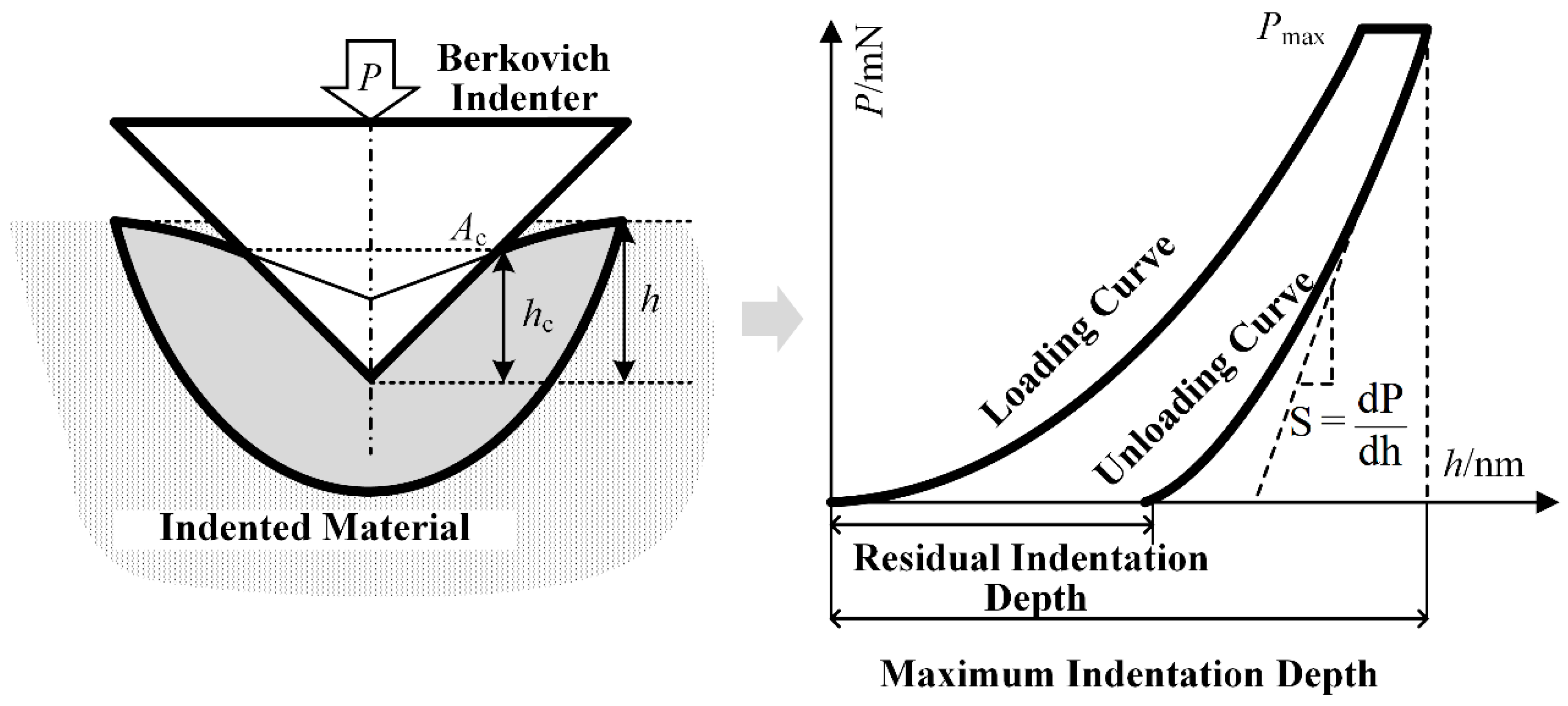

2.2.1. Principle of Nanoindentation Testing

2.2.2. Statistical Nanoindentation Principle

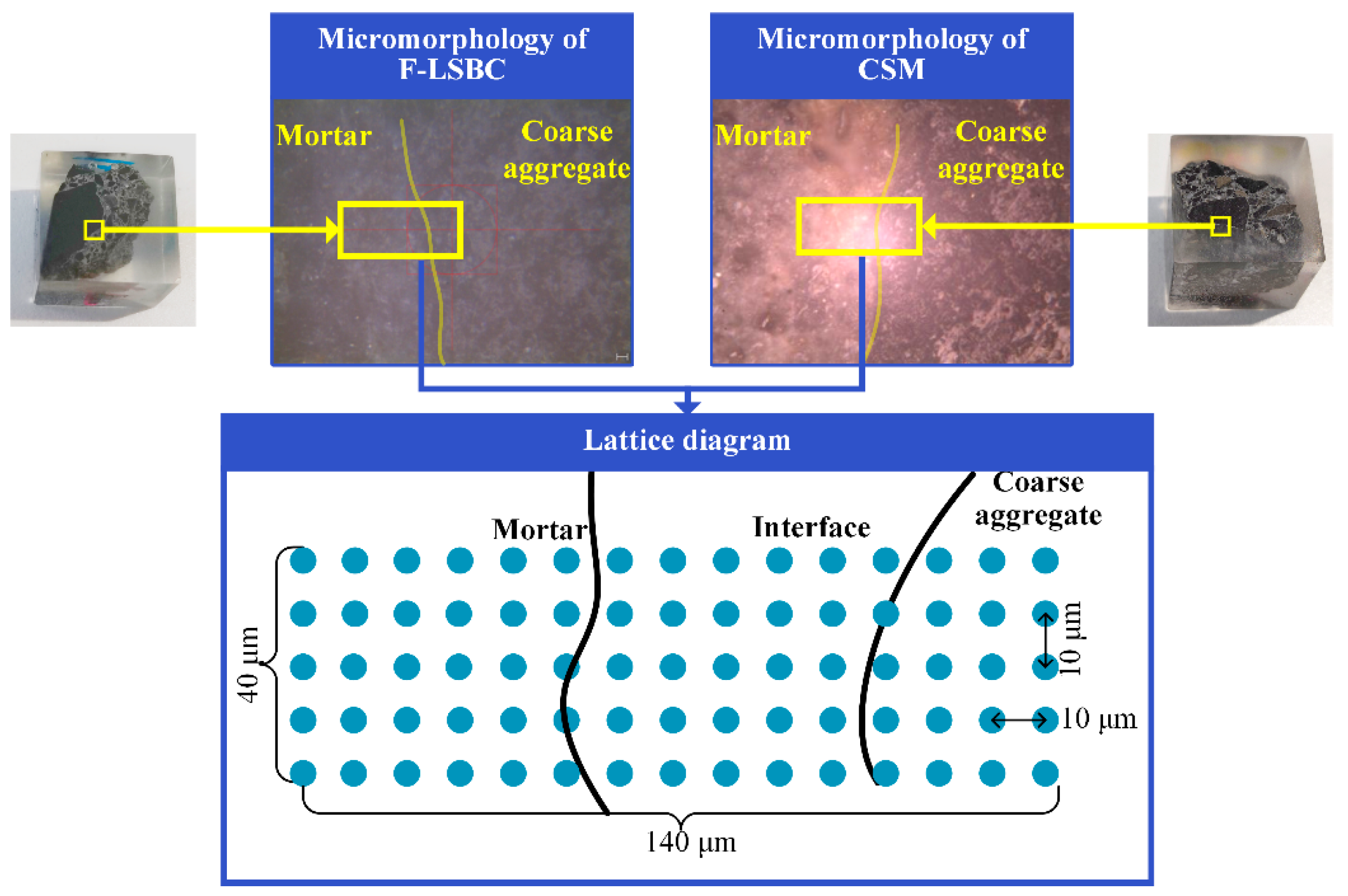

2.2.3. Fabrication of Nanoindentation Specimens

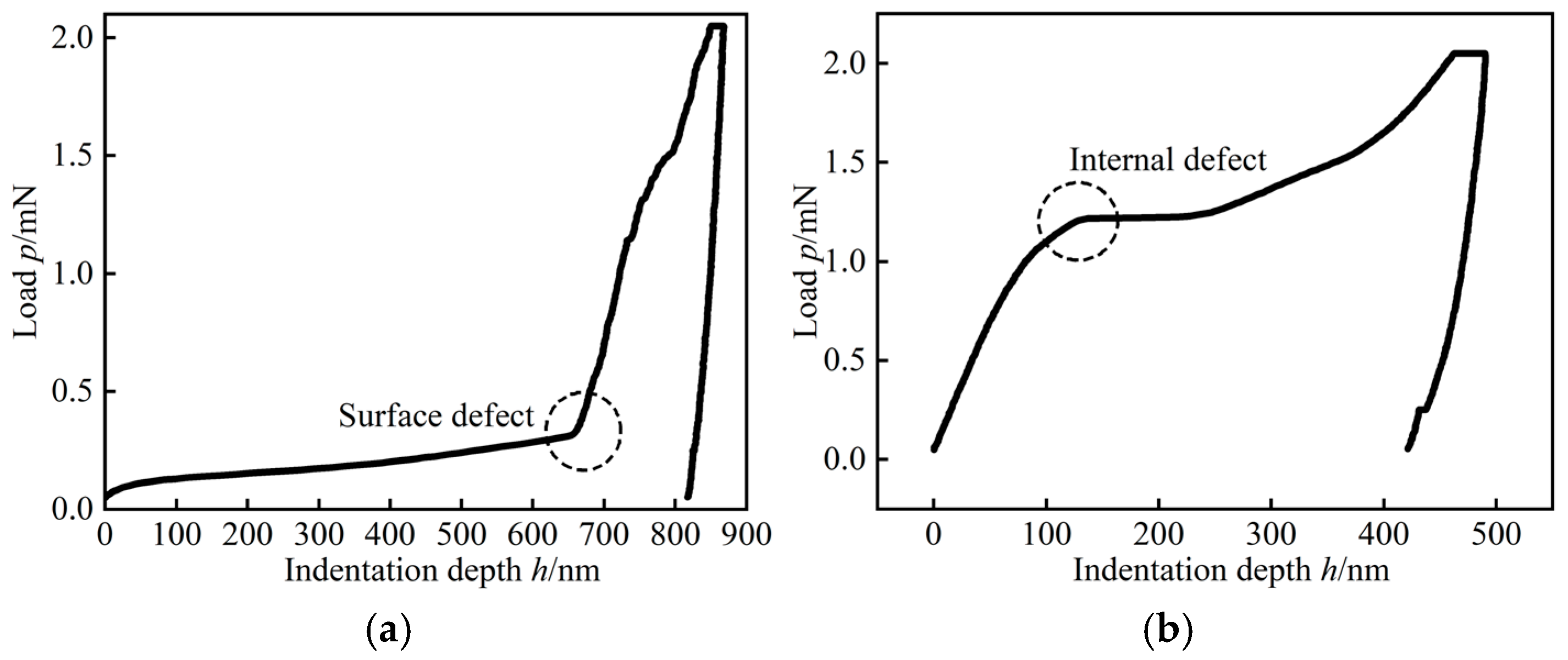

2.2.4. Test Parameters

2.3. Macroscopic Testing

2.3.1. Macroscopic Mechanical Properties Tests

2.3.2. Fatigue Performance Test

2.3.3. Dry Shrinkage Properties Test

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Micromechanical Properties

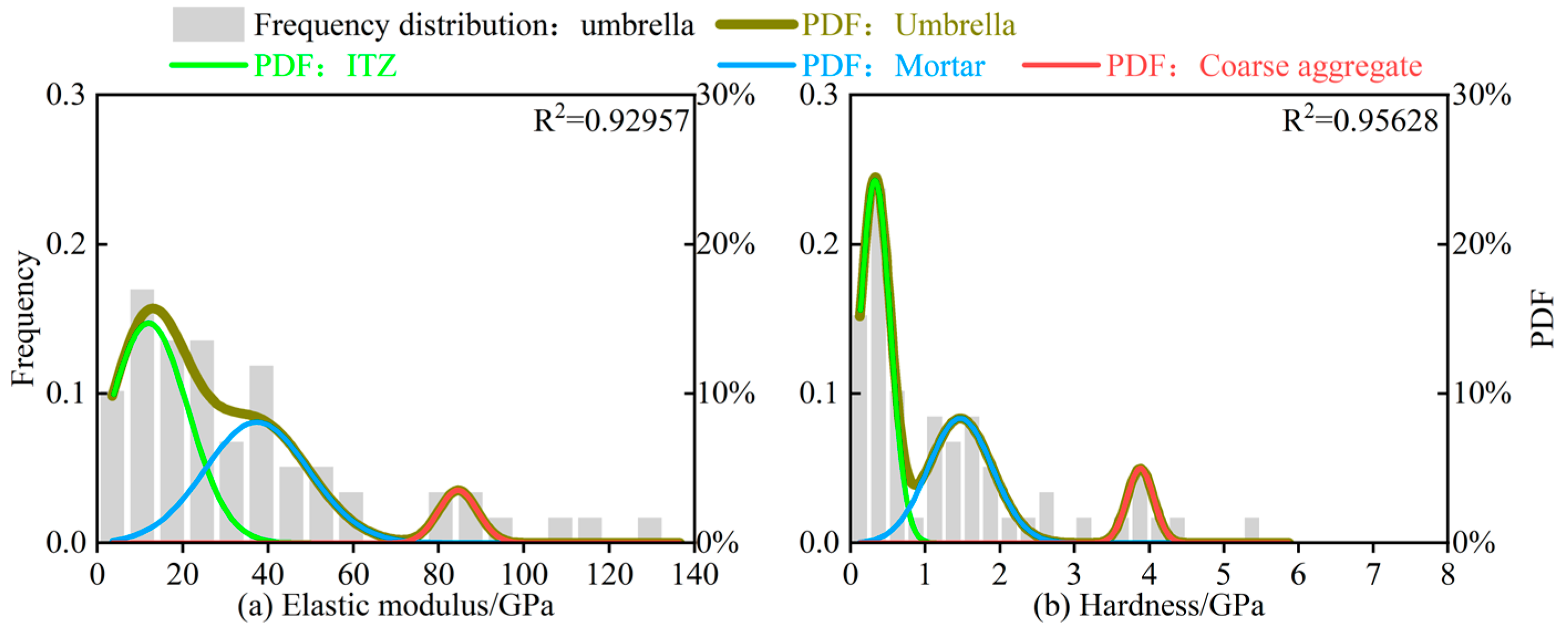

3.1.1. Deconvolution Analysis

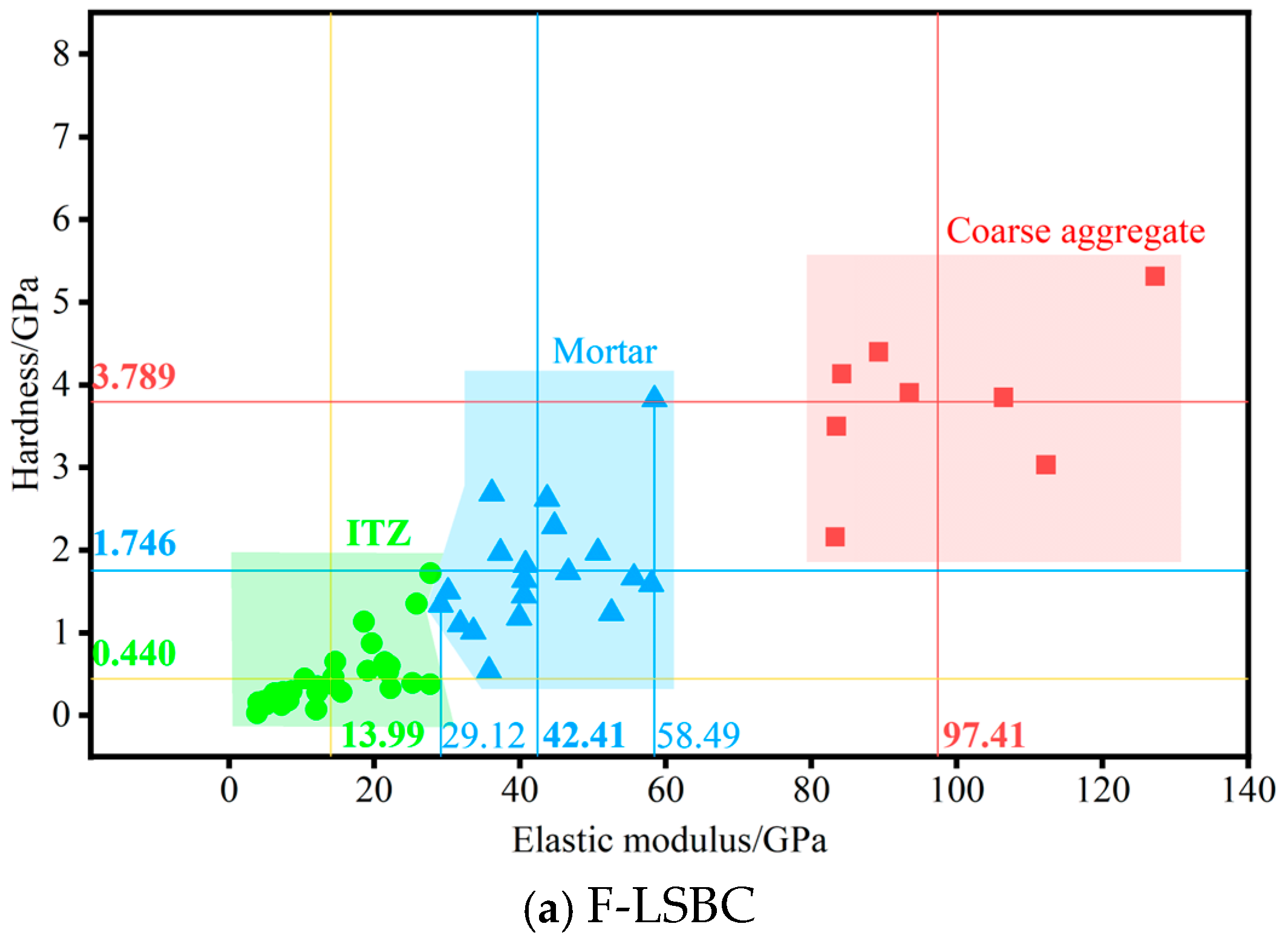

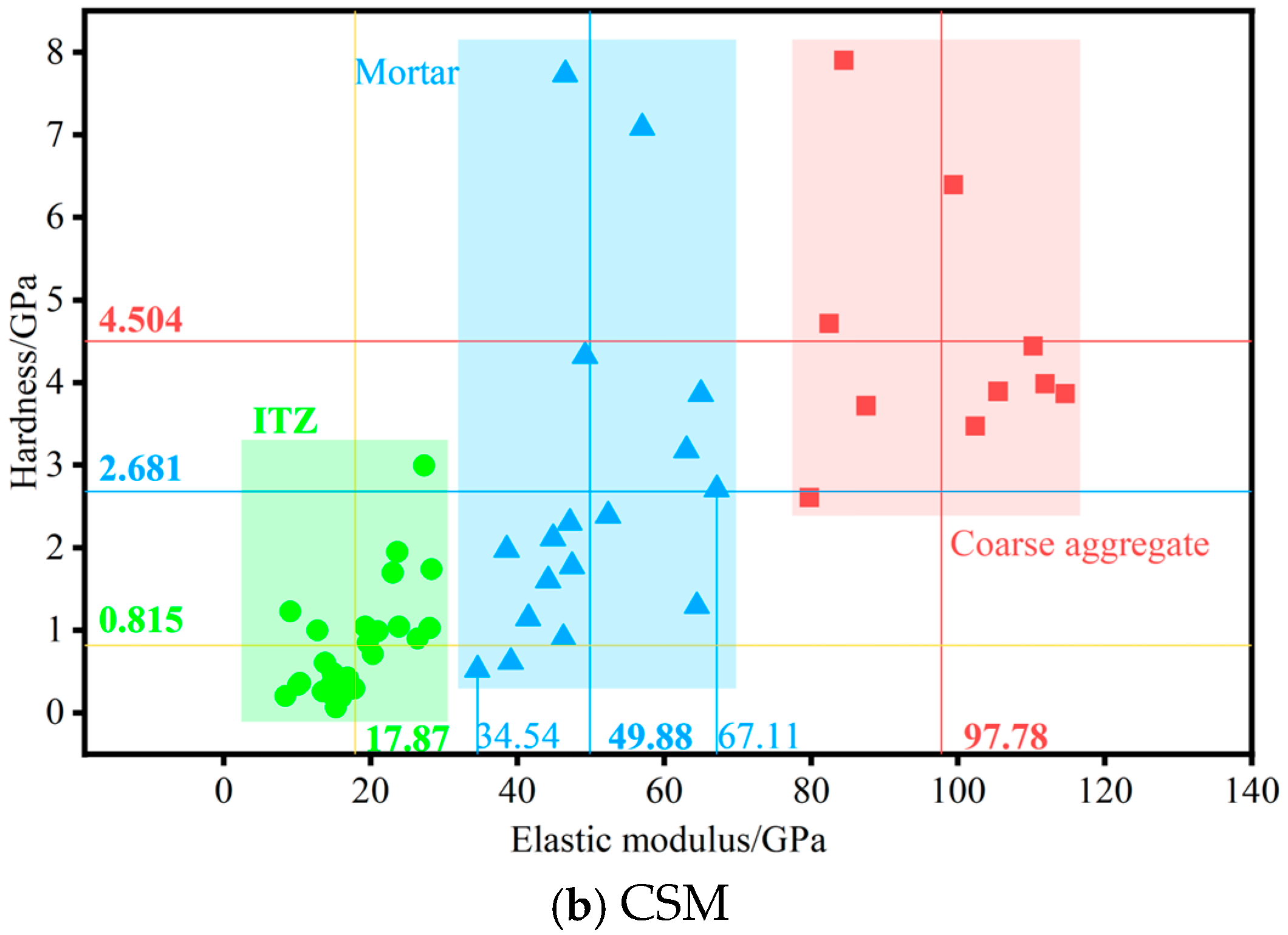

3.1.2. Cluster Analysis

3.1.3. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Elastic Modulus

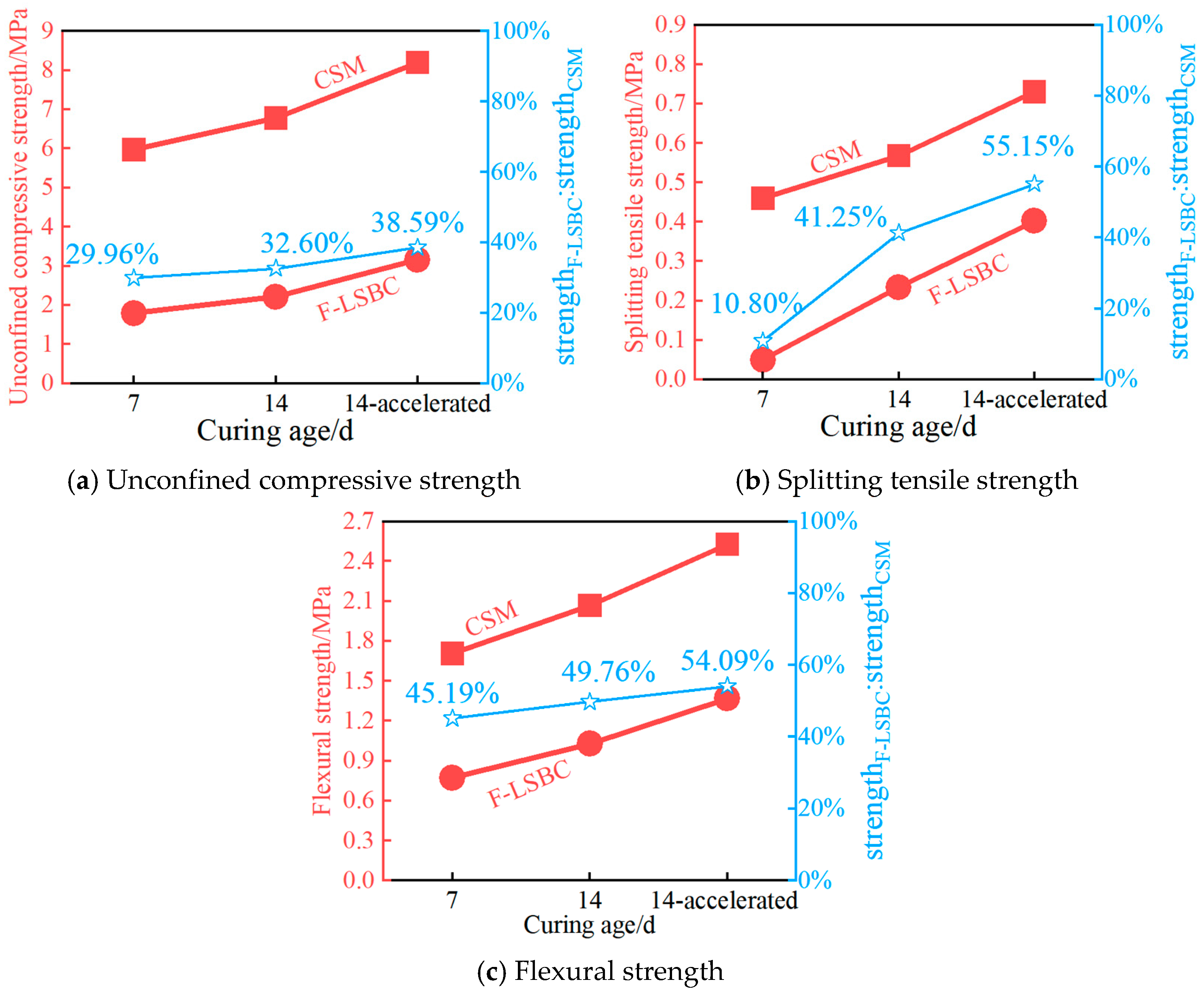

3.2. Microstructural Characteristics

3.3. Macroscopic Mechanical Properties

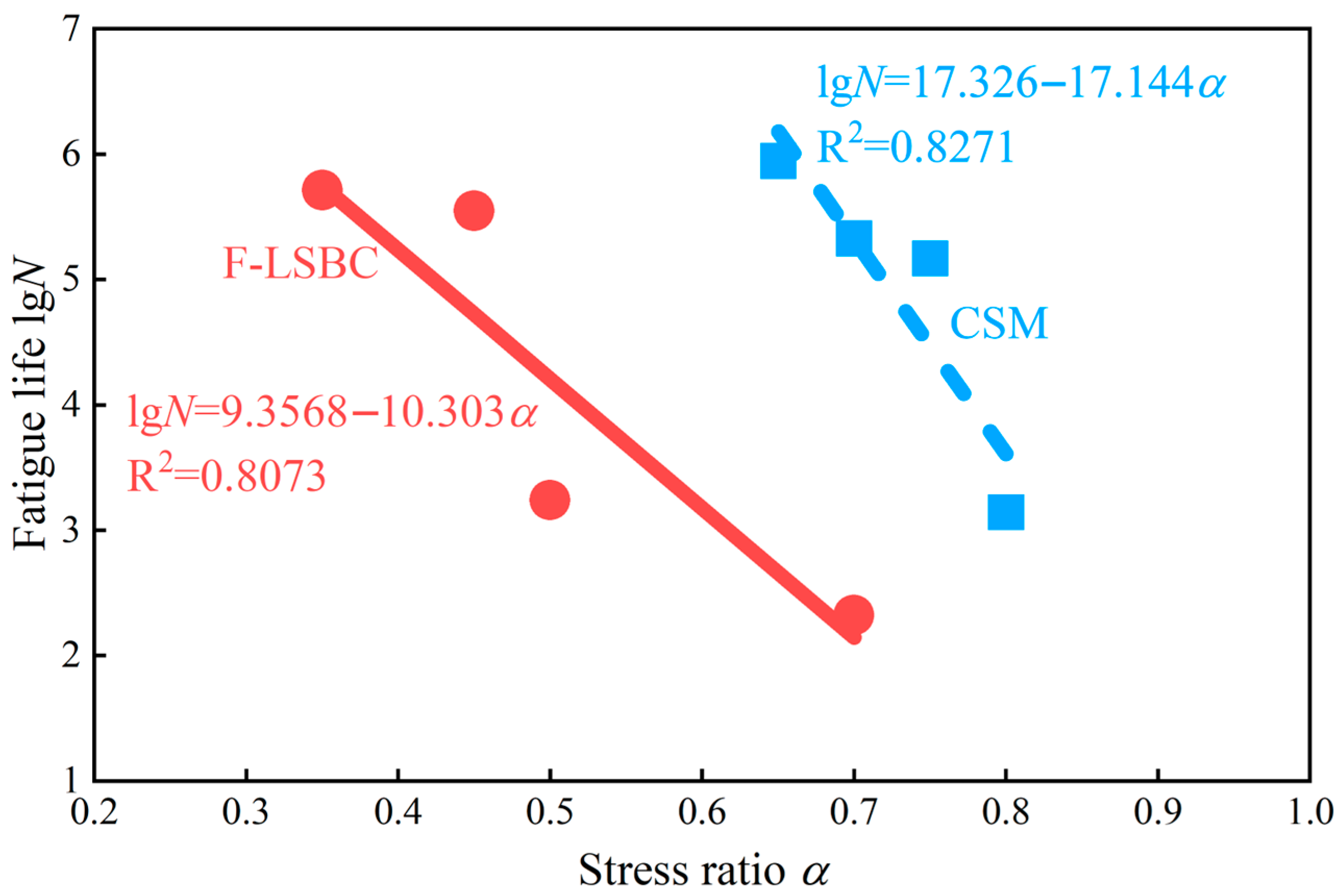

3.4. Fatigue Performance

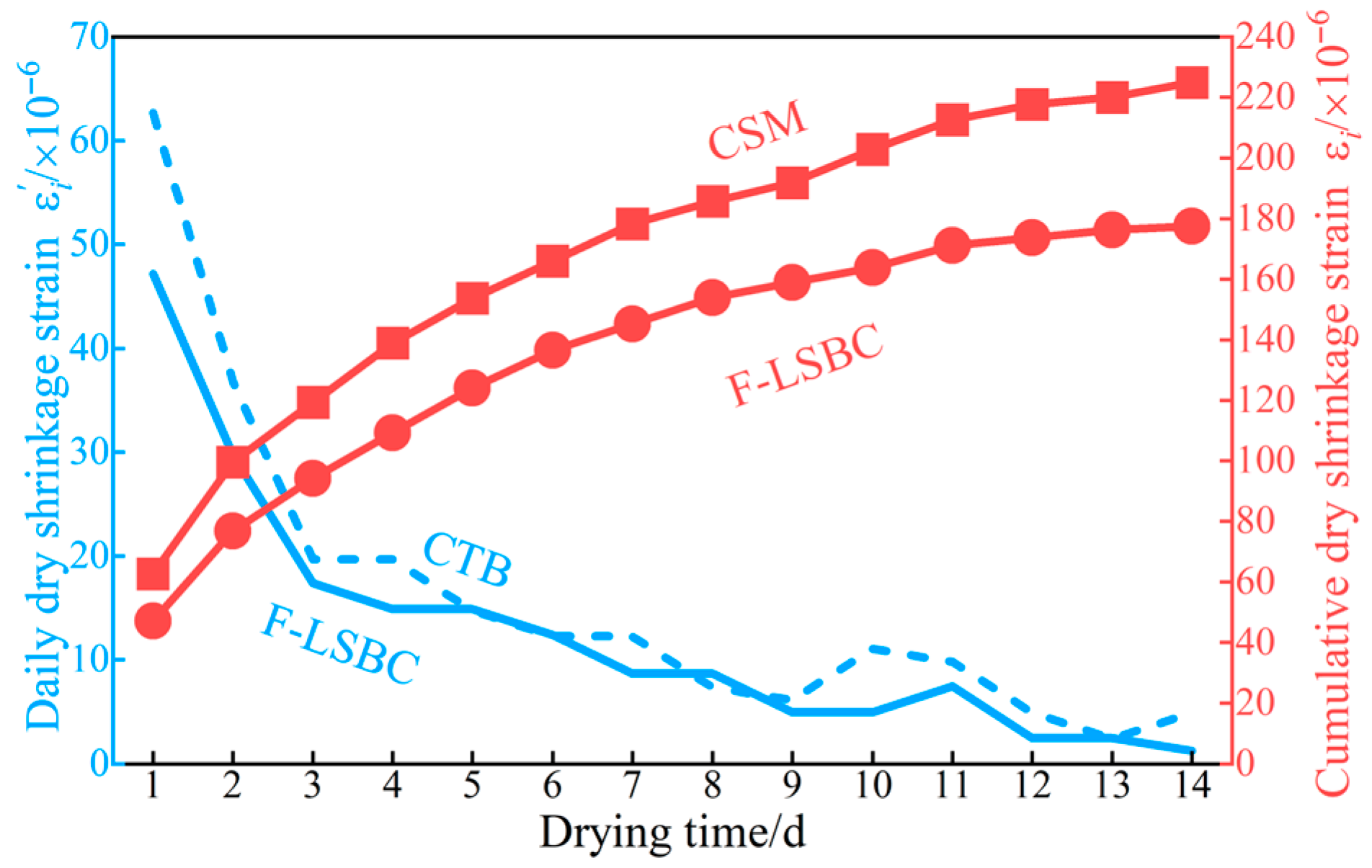

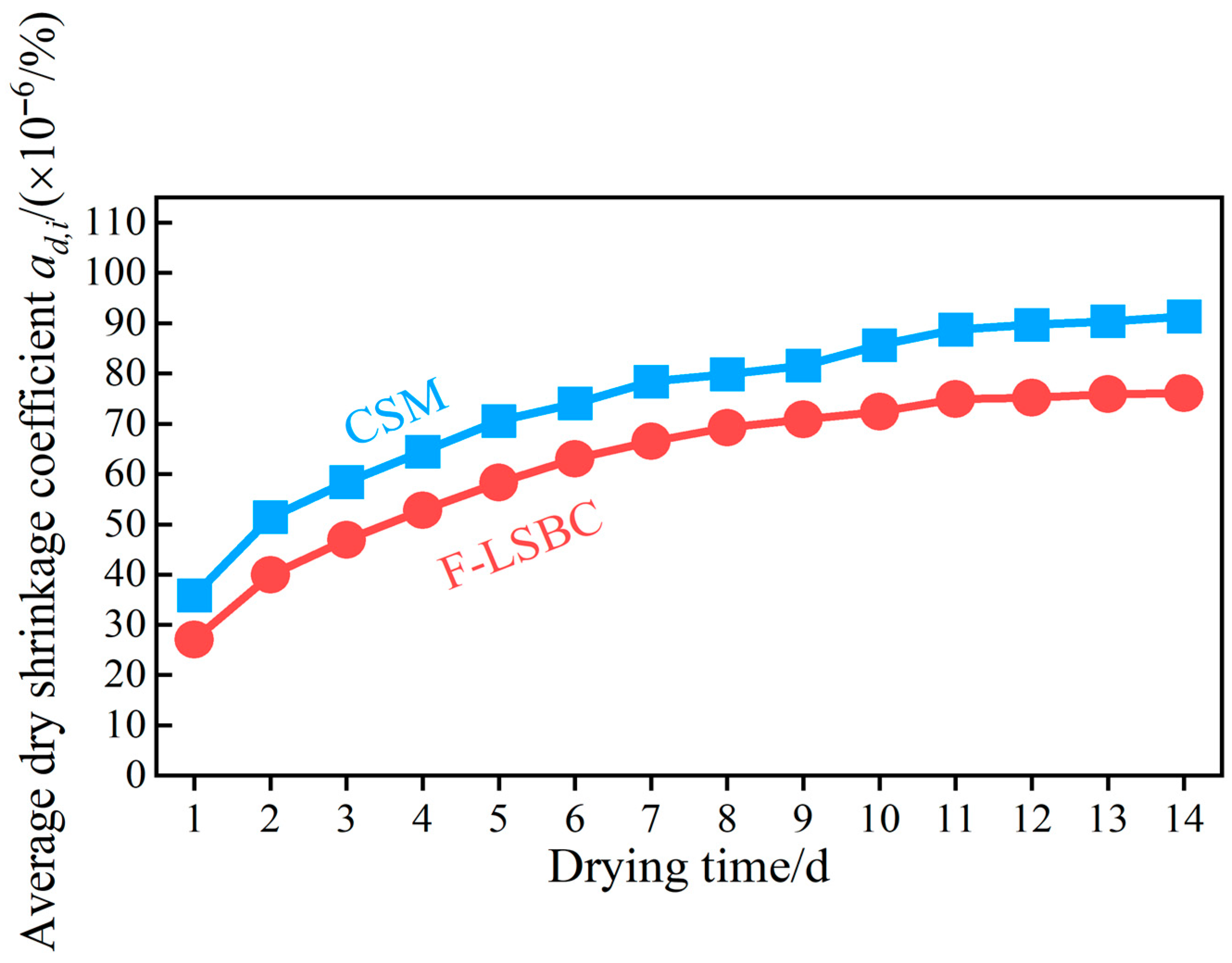

3.5. Dry Shrinkage Properties

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Nanoindentation and statistical analysis revealed that the ITZ in F-LSBC exhibits significantly lower elastic modulus and hardness, higher porosity, and greater thickness (55–90 μm) than that in CSM. These interfacial weaknesses are the primary cause of the observed mechanical degradation.

- (2)

- Due to ITZ deterioration, F-LSBC demonstrates markedly reduced compressive, tensile, and flexural strength, as well as shortened fatigue life, in comparison to CSM. This study quantitatively links ITZ properties with macroscopic mechanical behavior, offering a mechanistic understanding of performance loss.

- (3)

- Despite weaker strength, F-LSBC benefits from a high coarse aggregate content and a weak interface-induced “crack-without-displacement” mechanism, which effectively reduces drying shrinkage strain and delays shrinkage development.

- (4)

- The findings emphasize the critical role of ITZ characteristics in determining the durability and deformation behavior of cement-stabilized materials. Interface optimization is key to reconciling the strength–crack-resistance trade-off in F-LSBC, offering a pathway to improve the structural performance of semi-rigid base layers.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, P.; Cai, Y.; Jin, Z.; Moshtagh, E. Cracking resistance and mechanical properties of basalt fibers reinforced cement-stabilized macadam. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2019, 165, 312–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liang, N.; Xiang, Y.; Qin, M. Crack Resistance and Mechanical Properties of Polyvinyl Alcohol Fiber-Reinforced Cement-Stabilized Macadam Base. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 6564076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Yan, S.; Chen, X.; Dong, S.; Zhao, X.; Polaczyk, P. Review on the mesoscale characterization of cement-stabilized macadam materials. J. Road Eng. 2023, 3, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, A.; Mingard, K.; Lord, J.D.; Roebuck, B.; Tice, D.R.; Mottershead, K.J.; Fairweather, N.D.; Bradbury, A.K. Sensitivity of stress corrosion cracking of stainless steel to surface machining and grinding procedure. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 3398–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, N.; Elseifi, M.A.; Zhang, Z. Mitigation strategies for reflection cracking in rehabilitated pavements—A synthesis. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2016, 9, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Xiong, H.; Luo, R. A review and perspective for research on moisture damage in asphalt pavement induced by dynamic pore water pressure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 204, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, B. Experimental and simulation study on the expansion mechanism of polyurethane grout. Polymer 2024, 304, 127097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solatiyan, E.; Ho, V.T.; Bueche, N.; Vaillancourt, M.; Carter, A. Evaluation of Crack Development Through a Bituminous Interface Reinforced with Geosynthetic Materials by Using a Novel Approach. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023, 2677, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, Q. Study on the applicability of asphalt concrete skeleton in the semi-flexible pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 327, 126923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Han, D.; Yang, T.; Tang, D.; Huang, Y.; Tang, N.; Zhao, Y. Field observations and laboratory evaluations of asphalt pavement maintenance using hot in-place recycling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 271, 121864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.V.; Saride, S. Evaluation of cracking resistance potential of geosynthetic reinforced asphalt overlays using direct tensile strength test. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 162, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Xu, L.; Cao, Z.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Xiao, F. Interlayer distress characteristics and evaluations of semi-rigid base asphalt pavements: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 431, 136441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, K.; Bai, Y.; Wang, R. Impact of composition and knitting methods of fiberglass grid on the progression of reflective crack in asphalt pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 419, 135579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.-H.; Lee, K.-W.; Ryu, S.-W. Development of cement-treated base material for reducing shrinkage cracks. In Geomaterials 2006; Transportation Research Record-Series; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Volume 1952, pp. 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, P.; Ma, Z.; Li, H.; Gong, P.; Liu, Z.; Han, J.; Xu, M.; Hua, S. Evaluation of the shrinkage properties and crack resistance performance of cement-stabilized pure coal-based solid wastes as pavement base materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 421, 135680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.V.; Saride, S.; Zornberg, J.G. Fatigue performance of geosynthetic-reinforced asphalt layers. Geosynth. Int. 2021, 28, 584–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Li, J.; Yan, X.; Xiong, Z. Research Progress on the Activity Stimulation of Lithium Slag in Concrete. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Jin, Z.; Yang, J.; He, J.; Huang, X.; Ye, X.; Li, G.; Wang, C. Study on the Performance of Recycled Cement-Stabilized Macadam Mixture Improved Using Alkali-Activated Lithium Slag-Fly Ash Composite. Minerals 2024, 14, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, H.; Rupasinghe, M.; Sofi, M.; Sharma, R.; Ranzi, G.; Mendis, P.; Zhang, Z. A Review on Cementitious and Geopolymer Composites with Lithium Slag Incorporation. Materials 2024, 17, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Lin, Y.; Chen, S.; Sun, X.; Yang, X.; Huang, Q. Mechanical properties and repairing mechanism of recycled cement stabilized macadam for road base based on microbial induced carbonate precipitation technology. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhao, Y.; Ji, A.; Ding, Z. Enhancing recycled aggregates quality through biological deposition treatment. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 100, 111681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, C.; Li, M. Experimental study on cement stabilized macadam-gangue mixture in road base. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 2022, 42, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T/CECS G:K23-01-2019; Technical Specification for Large Stone Base Course Filled with Cement Stabilized Macadam. China Communication Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Pan, Y.; Han, D.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Xia, X.; Zhao, Y. Macroscopic properties and microscopic characterisation of an optimally designed anti-cracking stone base course filled with cement stabilised macadam. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2025, 26, 340–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Li, Z.; Ma, T.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Wang, J. Evaluation on the Crack Resistance of Cement-Stabilized Macadam Mixture with Crack-Resistant Interlocking Gap Gradation and Rubber Powder. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2024, 36, 04024269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, W.; Gan, Y.; Mahmood, A.H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, K. Nano- and Microscopic Investigation on the Strengthening Mechanism of ITZs Using Waste Glass Powder in Modeled Aggregate Concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2024, 36, 04024007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Pan, B.; Zhou, C.; Sun, Y.; Song, C. A novel insight into the interface fracture between magnesium phosphate cement mortar and cement concrete. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2220062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Han, L.; Wu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, R. Mix proportion design and production optimization of stone filled with cement stabilized macadam considering shrinkage resistance and easy construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Chen, A.; Lin, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, Y. Microscale characterization of an anti-cracking stone base course filled with cement stabilized macadam. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 425, 136037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Optimizing Composition of Cement-Treated Aggregates Based on Weakening Interface. Ph.D. Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.; Han, D.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, D.; Chen, Y. Experiment investigation on mix proportion optimization design of anti-cracking stone filled with cement stabilized macadam. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 393, 132136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JTG E51-2009; Test Methods of Materials Stabilized with Inorganic Binders for Highway Engineering. China Communication Press: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Long, X.; Dong, R.; Su, Y.; Chang, C. Critical Review of Nanoindentation-Based Numerical Methods for Evaluating Elastoplastic Material Properties. Coatings 2023, 13, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Shen, Z.; Lu, C.; Jia, Q.; Guan, C.; Chen, C.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. Reverse Analysis of Surface Strain in Elasto-Plastic Materials by Nanoindentation. Int. J. Appl. Mech. 2021, 13, 2150106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilakarathna, P.S.M.; Mendis, P.; Lee, H.; Chandrathilaka, E.R.K.; Vimonsatit, V.; Baduge, K.S.K. Multiscale modelling framework for elasticity of ultra high strength concrete using nano/microscale characterization and finite element representative volume element analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 327, 126968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.; Stephens, C.S.; Allison, P.G.; Sanchez, F. Effect of Carbon Nanofiber Clustering on the Micromechanical Properties of a Cement Paste. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L. M&S highlight: Constantinides et al. (2003), on the use of nanoindentation for cementitious materials. Mater. Struct. 2022, 55, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, G.; Ulm, F.-J. The nanogranular nature of C-S-H. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2007, 55, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Wang, Z. A review of the interfacial transition zones in concrete: Identification, physical characteristics, and mechanical properties. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 300, 109979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandamme, M.; Ulm, F.J. Viscoelastic solutions for conical indentation. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2006, 43, 3142–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Cripps, A.C. Critical review of analysis and interpretation of nanoindentation test data. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 200, 4153–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandamme, M.; Ulm, F.-J.; Fonollosa, P. Nanogranular packing of C-S-H at substochiometric conditions. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JB/T 12721-2016; In-Situ Nano-Indentation/Scratch Testing Instruments for Solid Materials-Technical Specification. China Machine Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Xiang, X.; Chen, W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, G.; Wu, J.; Tian, W. Application of recycled concrete aggregates in continuous-graded cement stabilized macadam. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Li, L.; Du, Y.; Li, F. Identification of interfacial transition zone in asphalt concrete based on nano-scale metrology techniques. Mater. Des. 2017, 129, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M.; Höpken, W. Clustering. In Applied Data Science in Tourism: Interdisciplinary Approaches, Methodologies, and Applications; Egger, R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 129–149. [Google Scholar]

- Korouzhdeh, T.; Eskandari-Naddaf, H.; Kazemi, R. The ITZ microstructure, thickness, porosity and its relation with compressive and flexural strength of cement mortar; influence of cement fineness and water/cement ratio. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2022, 16, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, R.W. Elastic-Moduli of a Solid Containing Spherical Inclusions. Mech. Mater. 1991, 12, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Huang, G.; Li, R.; Pei, J. Study on fatigue crack propagation failure in semi-rigid base. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 134007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JTG/T F20-2015; Technical Guidelines for Construction of Highway Roadbases. China Communication Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Lu, T.; Liang, X.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z. Experimental and numerical study on the mitigation of autogenous shrinkage of cementitious material. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 141, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Properties | Density/g·cm−3 | Fineness/ m2·kg−1 | Setting Time/Min | Compressive Strength/MPa | Flexural Strength/MPa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Setting | Final Setting | 3 d | 28 d | 3 d | 28 d | |||

| Test result | 3.065 | 345 | 150 | 240 | 22.6 | 54.5 | 4.8 | 9.1 |

| Requirement | ≥300 | ≥45 | ≤600 | ≥17.0 | ≥42.5 | ≥3.5 | ≥6.5 | |

| Category | Sieve Size /mm | The Original Gradation of the Limestone Aggregate | Synthetic Gradations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | 2# | 3# | CSM | F-LSBC | ||

| Aggregate gradation (passing rate, %) | 26.5 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 19 | 34.6 | 100 | 100 | 84.63 | 17.56 | |

| 16 | 10.27 | 100 | 100 | 78.91 | 17.56 | |

| 13.2 | 0 | 80.73 | 100 | 69.85 | 17.56 | |

| 9.5 | 0 | 33.88 | 100 | 53.69 | 17.56 | |

| 4.75 | 0 | 1.34 | 99.89 | 42.42 | 17.56 | |

| 2.36 | 0 | 0 | 70.54 | 29.63 | 17.56 | |

| 1.18 | 0 | 0 | 51.16 | 21.49 | 11.29 | |

| 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 33.98 | 14.27 | 7.89 | |

| 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 23.52 | 9.88 | 6.33 | |

| 0.15 | 0 | 0 | 14.37 | 6.04 | 3.96 | |

| 0.075 | 0 | 0 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 3.16 | |

| Mass fraction of synthetic gradation for CSM | 23.50% | 34.50% | 42.00% | 100% | / | |

| Density/g·cm−3 | Apparent density | 2.739 | 2.739 | 2.725 | 2.733 | / |

| Bulk volume density | 2.703 | 2.698 | 2.725 | 2.711 | / | |

| Mass fraction of mineral aggregates | Coarse aggregate | / | / | / | 57.58% | 82.44% |

| Fine aggregate | / | / | / | 42.42% | 17.56% | |

| Fine-to-coarse aggregate ratio | / | / | / | 0.734 | 0.213 | |

| Indicators | Material Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filler | F-LSBC | CSM | ||

| Cement Content/% | 30 | 5.27 | 52.7 | |

| Compaction Test Results | /g·cm−3 | 2.240 | 2.294 | 2.391 |

| /% | 8.27 | 1.79 | 3.87 | |

| Volumetric indicators | /% | / | 33.17 | 51.56 |

| /% | / | 15.11 | 12.31 | |

| Materials | Statistical Indicators | Elastic Modulus/GPa | Hardness/GPa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITZ | Mortar | Coarse Aggregate | ITZ | Mortar | Coarse Aggregate | ||

| F-LSBC | Mean value | 11.99 | 37.38 | 84.54 | 0.325 | 1.469 | 3.88 |

| Standard deviation | 3.61 | 9.62 | 3.18 | 0.017 | 0.067 | 0.071 | |

| Volume fraction | 49.46% | 48.33% | |||||

| CSM | Mean value | 19.13 | 44.34 | 89.42 | 0.576 | 1.900 | 4.017 |

| Standard deviation | 1.35 | 2.33 | 7.97 | 0.073 | 0.168 | 0.055 | |

| Volume fraction | 30.09% | 38.27% | |||||

| Dry Shrinkage Characteristics | Data Source | Materials | Regression Equation | R2 | ID Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 14 | F-LSBC | 0.9941 | (11) | ||

| CSM | 0.9937 | (12) | |||

| Figure 15 | F-LSBC | 0.9934 | (13) | ||

| CSM | 0.9973 | (14) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ran, J.; Wang, H.; Tang, D.; Zhang, N.; Li, M.; Jia, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y. Macroscopic and Microscopic Performance Study of Filling-Type Large-Size Cement-Stabilized Macadam. Materials 2025, 18, 5501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245501

Ran J, Wang H, Tang D, Zhang N, Li M, Jia Y, Ma L, Zhang Y. Macroscopic and Microscopic Performance Study of Filling-Type Large-Size Cement-Stabilized Macadam. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245501

Chicago/Turabian StyleRan, Jin, Hailin Wang, Dong Tang, Naitian Zhang, Meiling Li, Yanshun Jia, Lianxia Ma, and Yinbo Zhang. 2025. "Macroscopic and Microscopic Performance Study of Filling-Type Large-Size Cement-Stabilized Macadam" Materials 18, no. 24: 5501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245501

APA StyleRan, J., Wang, H., Tang, D., Zhang, N., Li, M., Jia, Y., Ma, L., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Macroscopic and Microscopic Performance Study of Filling-Type Large-Size Cement-Stabilized Macadam. Materials, 18(24), 5501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245501