Phase Transition Behavior and Threshold Characteristics of GeTe Thin Films Under Single-Pulse Nanosecond Laser Irradiation

Abstract

1. Introduction

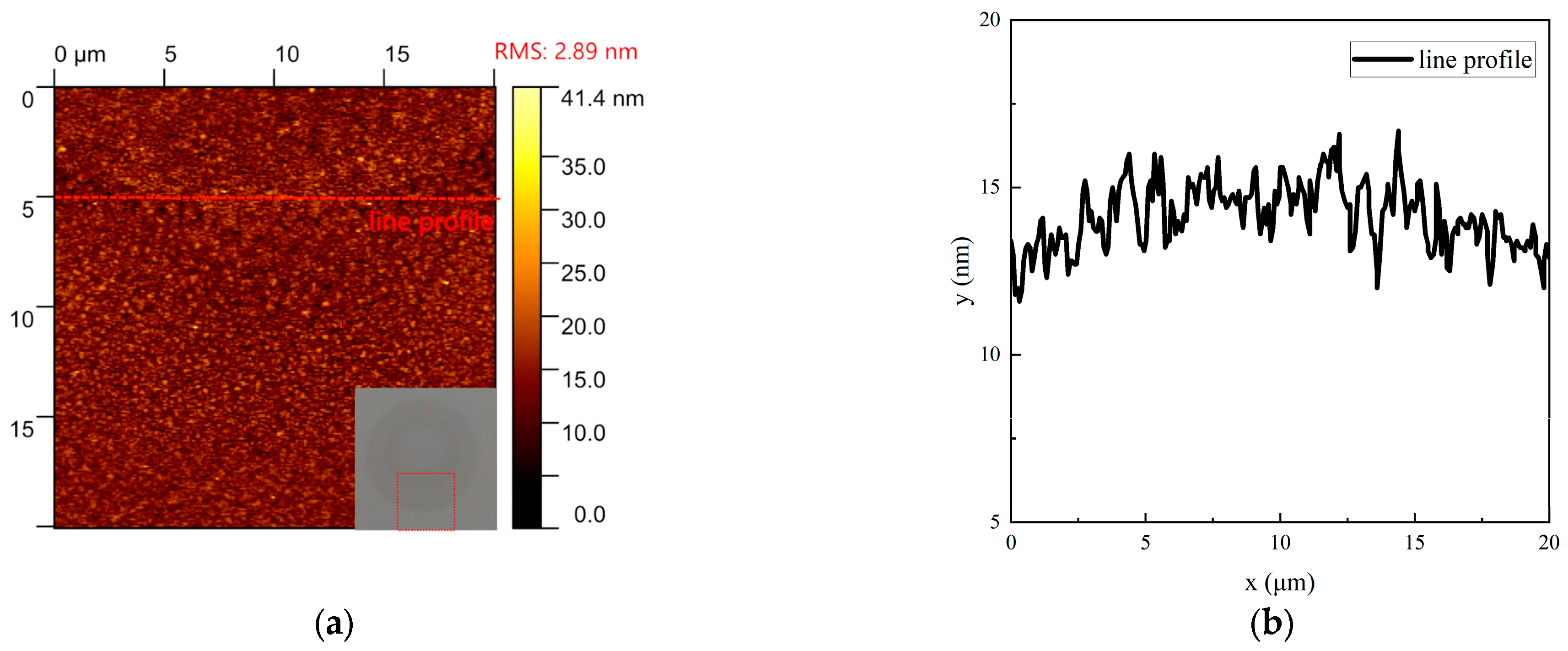

2. Materials and Methods

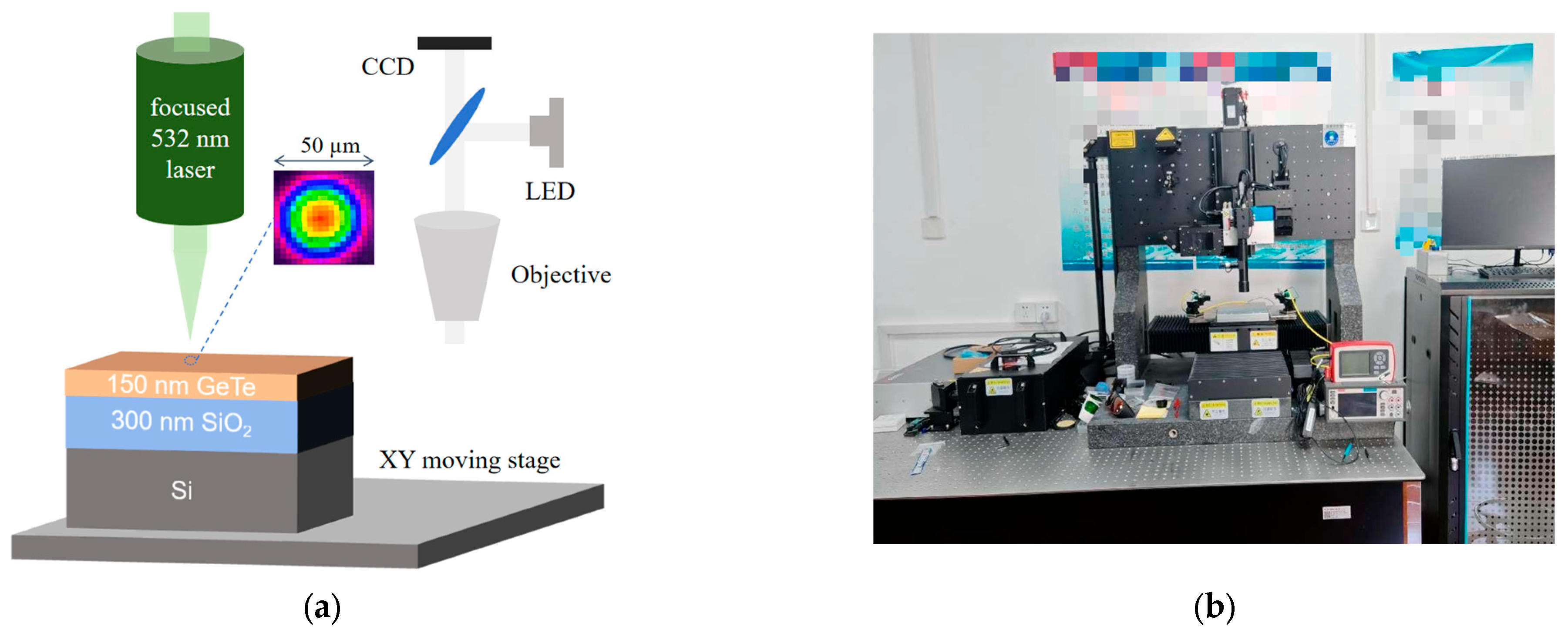

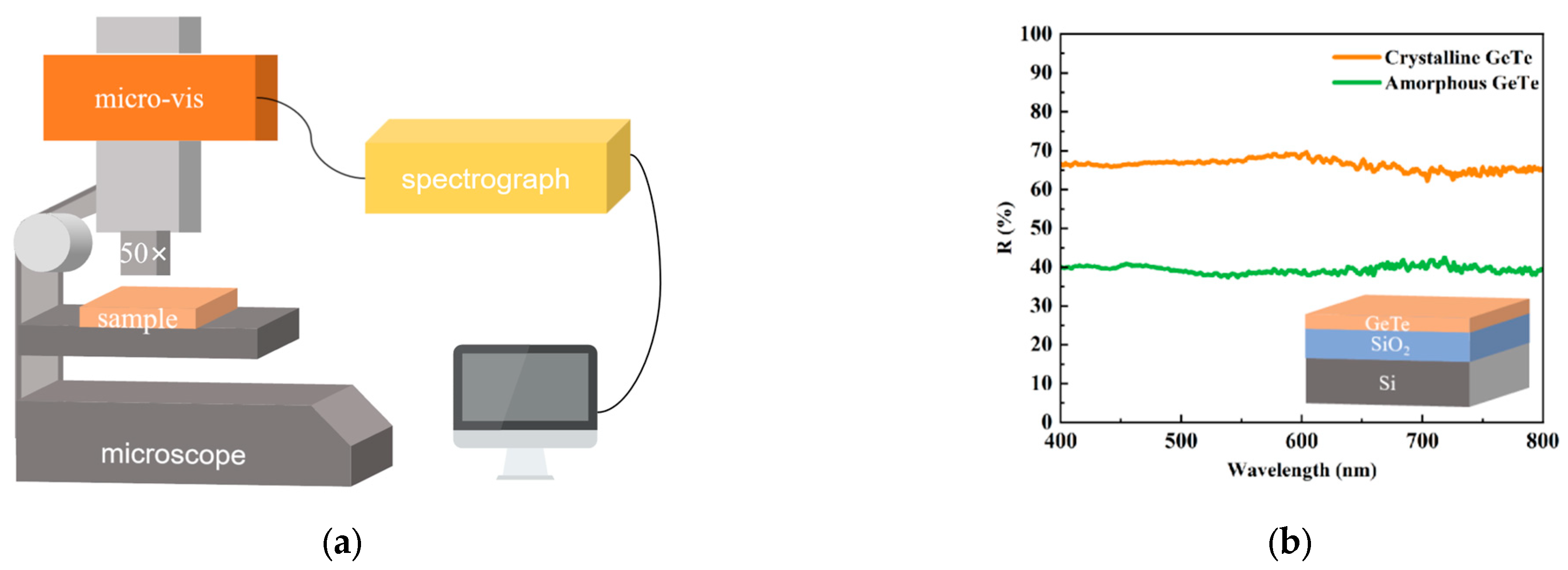

2.1. Experimental Setup

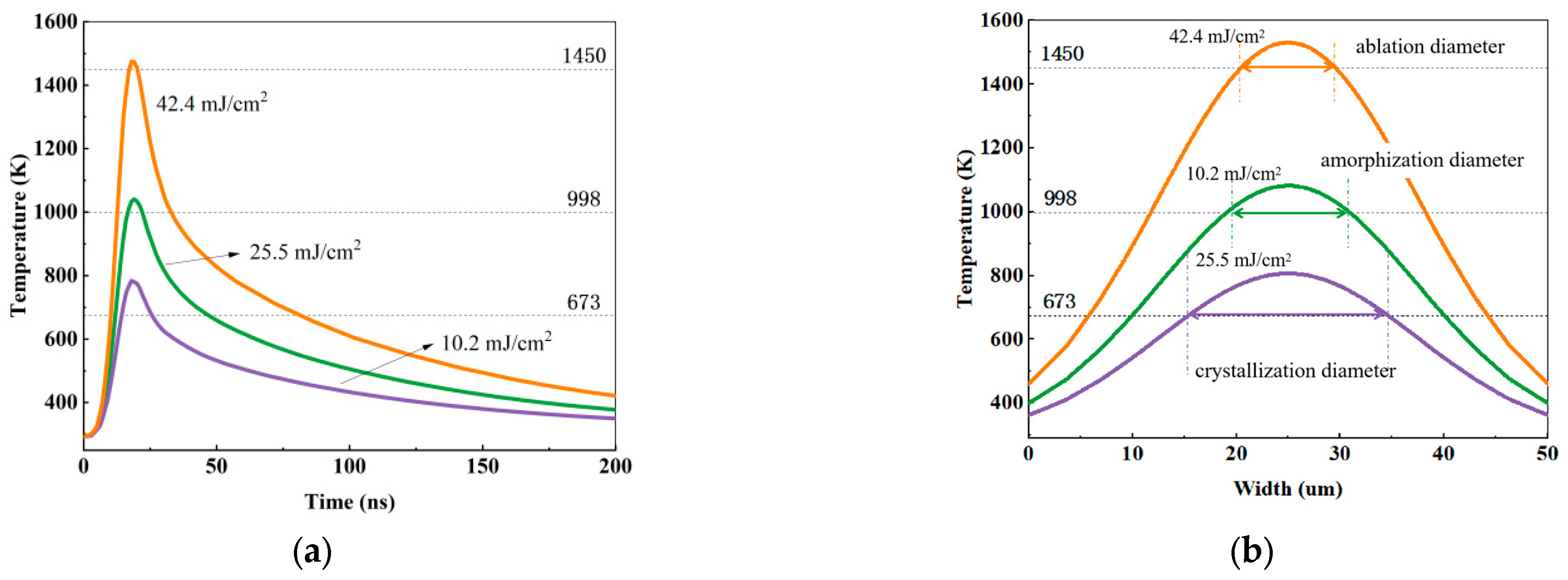

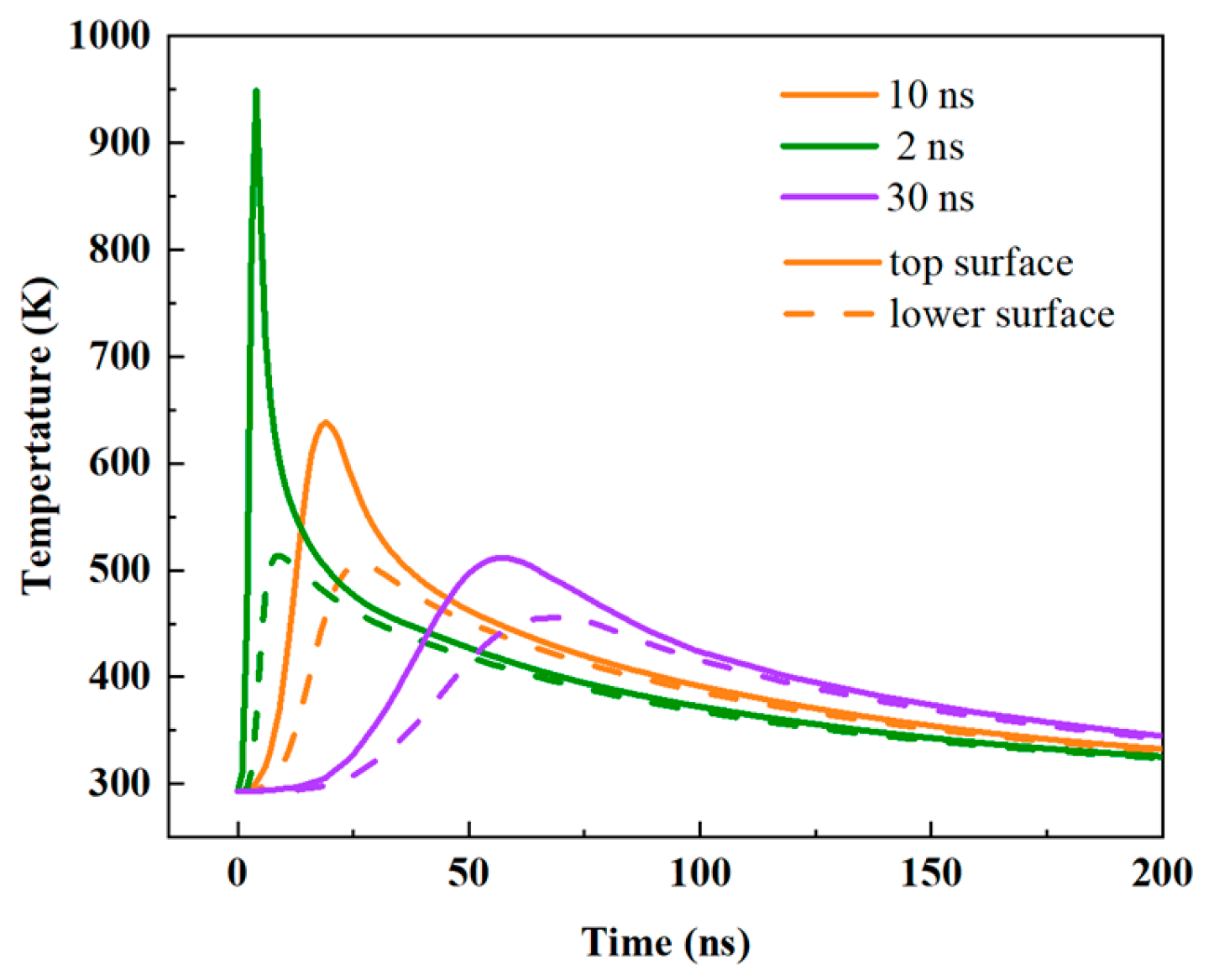

2.2. Theoretical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Amorphization Behavior

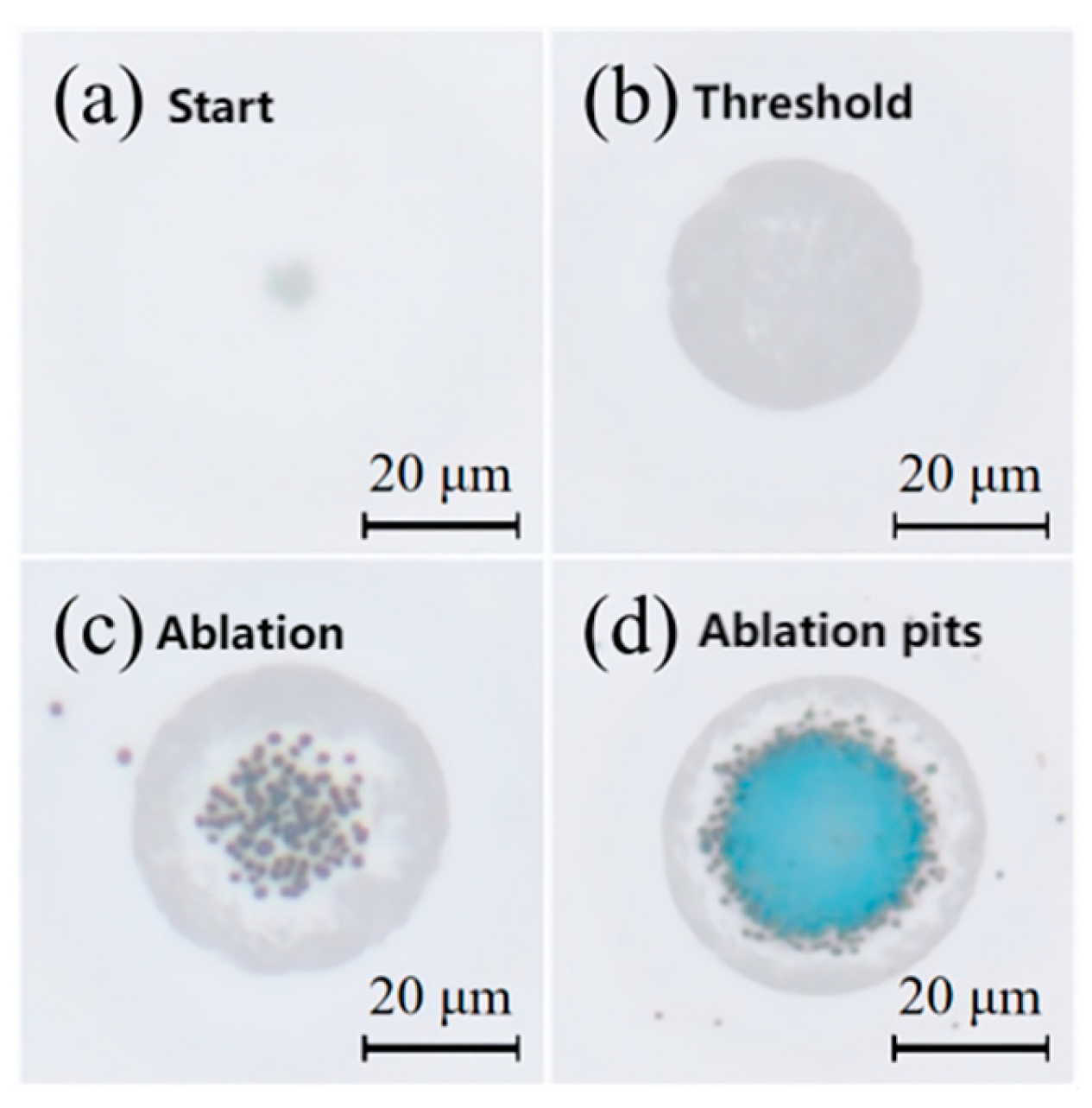

- Initial stage (<25.44 mJ/cm2): No significant morphological changes were observed.

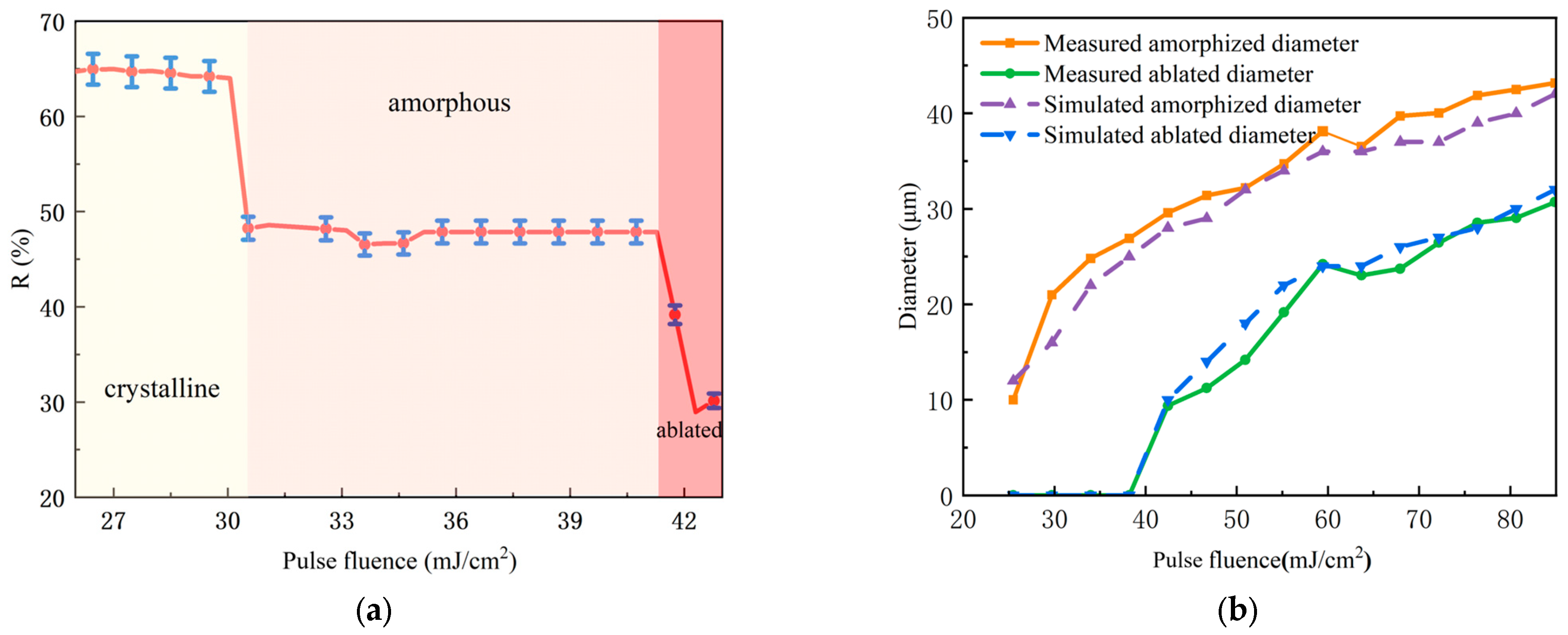

- Amorphization stage (25.44–41.28 mJ/cm2): This higher fluence range delivered enough energy to completely melt the GeTe film (temperature > 998 K). Gray circular spots emerged, indicating phase transition (Figure 5a). The diameter of amorphized regions increased with laser power, attributed to the radial threshold gradient of the Gaussian energy profile (Figure 5b). The reflectivity of the amorphized region decreased to 47% ± 2%. The simulated laser fluence threshold was verified by micro-spectroscopic measurements. The detected reflectance change occurred at a slightly lower fluence than that needed for an optically visible spot, as the spectroscopic method is more sensitive to incipient phase transitions. In the fluence of 38 mJ/cm2, the maximum ablation-free amorphized diameter reached 25 μm.

- Ablation stage (>41.28 mJ/cm2): The spot coverage approached 50 μm, with the expansion rate decreasing as ablation initiated (Figure 5c). Further increasing the fluence causes the central temperature to exceed the ablation threshold, leading to observable ablation. The resulting surface became populated with particulates, consequently enhancing diffuse scattering and reducing the measured reflectance to around 30%. Ultimately, at the highest fluences, the blue SiO2 substrate was exposed, confirming the complete ejection of GeTe from the central region.

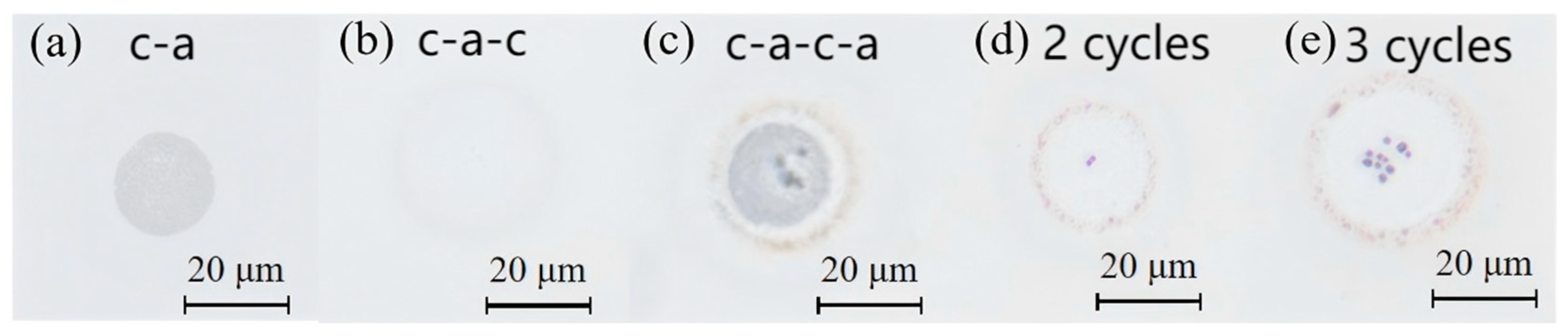

3.2. Crystallization Behavior

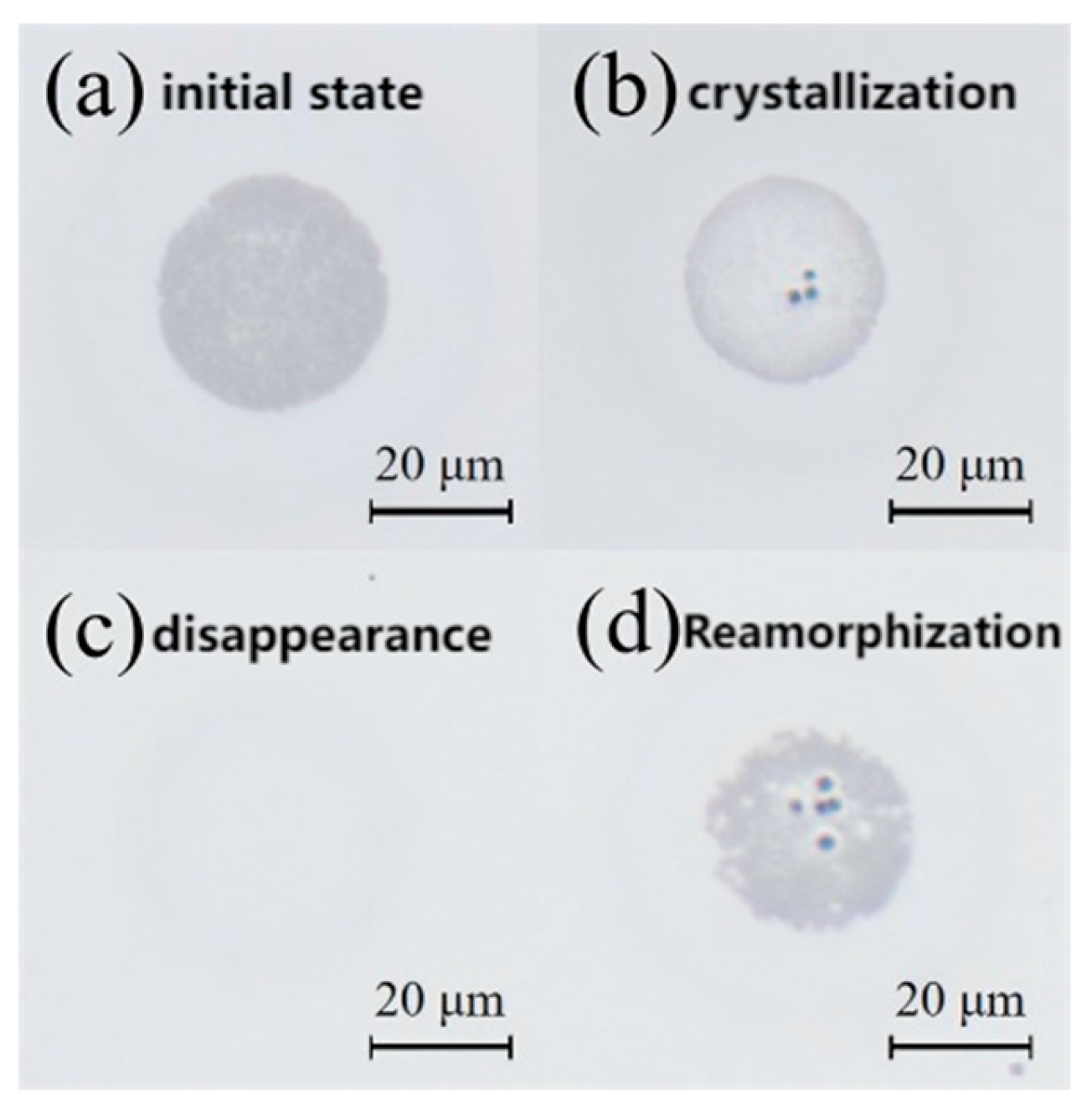

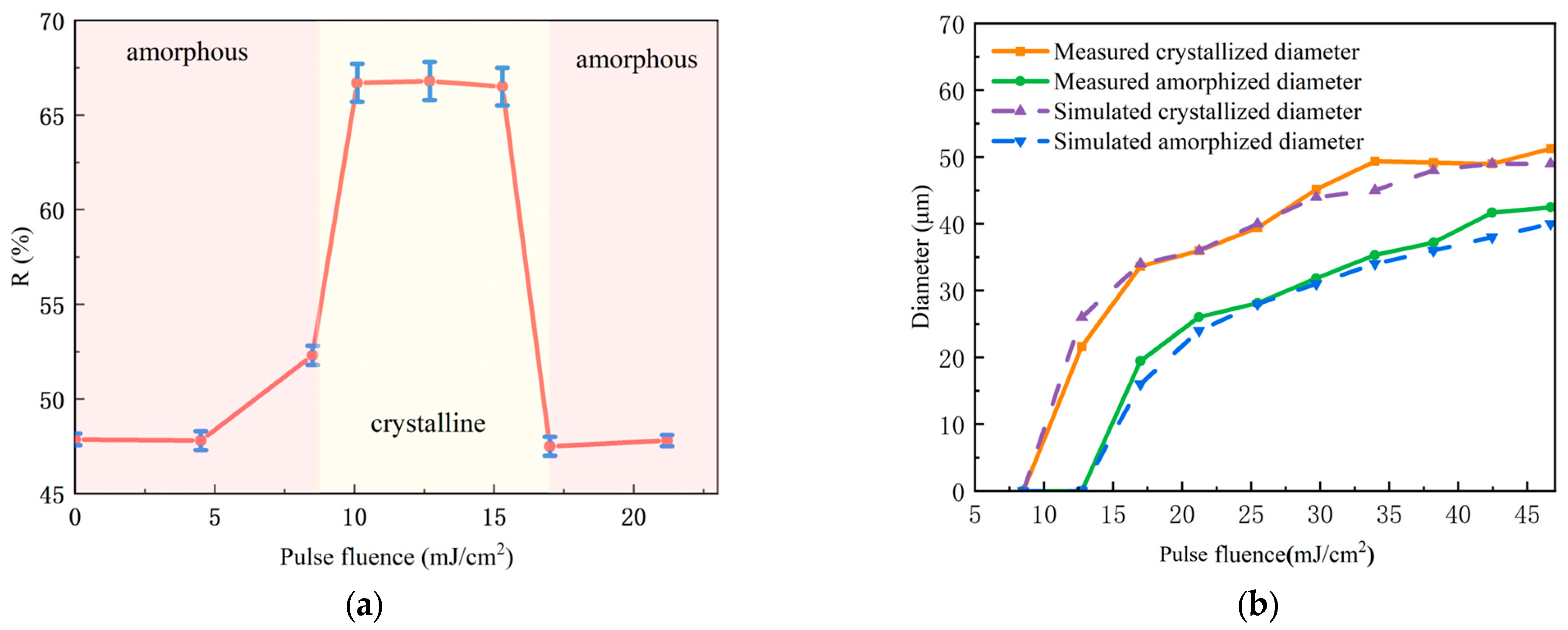

- Initial state: When there is no pulse excitation or the pulse energy is lower than 8.5 mJ/cm2, the original amorphous state is maintained.

- Crystallization (8.5–15 mJ/cm2): Within this range, the laser energy deposition is sufficient to raise the film temperature above the crystallization temperature (~673 K) but below the melting point (~998 K). When laser fluence exceeds 8.5 mJ/cm2, the degree of amorphization weakens and the reflectivity increases; when laser fluence exceeds 10.2 mJ/cm2, the amorphous spot completely disappears. At this point, the surface reflectivity of GeTe film is about 67%, which has been crystallized. This energy input provides the necessary thermal activation for atomic rearrangement, allowing for the growth of crystallized nuclei from the amorphous matrix through a solid-phase crystallization mechanism.

- Reamorphization state (>15 mJ/cm2): Further increasing fluence causes the central region temperature to exceed the amorphous threshold, leading to reamorphization, and the reflectivity level of GeTe film returns to amorphous state.

4. Conclusions

- The threshold fluences were quantitatively determined: recrystallization occurs at 8.5 mJ/cm2, while melt-quenching amorphization requires 25.4 mJ/cm2, consistent with coupled thermal–optical simulations and time-resolved reflectometry.

- Morphological degradation—including increased roughness, nanoscale protrusions, and cyclical ablative loss—currently limits endurance. This underscores the material-level challenge in achieving high-cycle operability.

- For the realization of reliable optically addressable phase-change devices, future efforts should concentrate on (i) optimizing GeTe stoichiometry and interfacial adhesion, (ii) developing engineered beam profiles with flat-top intensity distributions, and (iii) investigating the early stages of degradation to implement predictive failure mitigation strategies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GeTe | Germanium telluride |

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscope |

| CCD | Charge-Coupled Device |

| RF | Radio-Frequency |

| GST | GeSbTe |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| RMS | Root-Mean-Square Error |

References

- Bahl, S.K.; Chopra, K.L. Amorphous versus Crystalline GeTe Films. III. Electrical Properties and Band Structure. J. Appl. Phys. 1970, 41, 2196–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wełnic, W.; Botti, S.; Reining, L.; Wuttig, M. Origin of the optical contrast in phase-change materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 236403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuttig, M.; Bhaskaran, H.; Taubner, T. Phase-change materials for non-volatile photonic applications. Nat. Photonics 2017, 11, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, E.K.; Shi, L.P.; Zhao, R.; Lim, K.G.; Chong, T.C.; Schlesinger, T.E.; Bain, J.A. Low resistance, high dynamic range reconfigurable phase change switch for radio frequency applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 418–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Mansour, R.R. Experimental Investigation of Performance, Reliability, and Cycle Endurance of Nonvolatile DC-67 GHz Phase-Change RF Switches. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2021, 69, 4697–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fowler, C.; Liang, J.; Azhar, B.; Shalaginov, M.Y.; Deckoff-Jones, S.; An, S.; Chou, J.B.; Roberts, C.M.; Liberman, V.; et al. Electrically reconfigurable non-volatile metasurface using low-loss optical phase-change material. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Eom, S.H.; Lee, H.; Da Silva, J.L.; Kang, Y.S.; Lee, T.Y.; Khang, Y.H. Optical Properties of Pseudobinary Gete, Ge2sb2te5, Gesb2te4, Gesb4te7, And Sb2te3 from Ellipsometry and Density Functional Theory. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 115209. [Google Scholar]

- Gaković, B.; Petrović, S.; Siogka, C.; Milovanović, D.; Momčilović, M.; Tsibidis, G.D.; Stratakis, E. Selective Ablation and Laser-Induced Periodical Surface Structures (LIPSS) Produced on (Ni/Ti) Nano Layer Thin Film with Ultra-Short Laser Pulses. Photonics 2024, 11, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laprais, C.; Zrounba, C.; Bouvier, J.; Blanchard, N.; Bugnet, M.; Gassenq, A.; Gutiérrez, Y.; Vazquez-Miranda, S.; Espinoza, S.; Thiesen, P.; et al. Reversible Single-Pulse Laser-Induced Phase Change of Sb2S3 Thin Films: Multi-Physics Modeling and Experimental Demonstrations. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2401214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crunteanu, A.; Huitema, L.; Orlianges, J.C.; Guines, C.; Passerieux, D. Optical switching of GeTe phase change materials for high-frequency applications. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Workshop Series on Advanced Materials and Processes for RF and THz Applications (IMWS-AMP), Pavia, Italy, 20–22 September 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gawelda, W.; Siegel, J.; Afonso, C.N.; Plausinaitiene, V.; Abrutis, A.; Wiemer, C. Dynamics of laser-induced phase switching in GeTe films. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 123102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Thelander, E.; Lorenz, P.; Gerlach, J.W.; Decker, U.; Rauschenbach, B. Nanosecond laser-induced phase transitions in pulsed laser deposition-deposited GeTe films. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 116, 133501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salicio, O.; Wiemer, C.; Fanciulli, M.; Gawelda, W.; Siegel, J.; Afonso, C.N.; Plausinaitiene, V.; Abrutis, A. Effect of pulsed laser irradiation on the structure of GeTe films deposited by metal organic chemical vapor deposition: A Raman spectroscopy study. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 33520–33521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Thelander, E.; Gerlach, J.W.; Decker, U.; Rauschenbach, B. Crystallization kinetics of GeTe phase-change thin films grown by pulsed laser deposition. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2015, 48, 295304–295306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoux, S.; Cabral, C.; Krusin-Elbaum, L.; Jordan-Sweet, J.L.; Virwani, K.; Hitzbleck, M.; Salinga, M.; Madan, A.; Pinto, T.L. Phase transitions in Ge–Sb phase change materials. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 064918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Gao, L.; Peng, Y.; Qu, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, N.; Zhang, J. Novel four-port RF phase change switches based on GeTe thin film. J. Micromechanics Microeng. 2023, 33, 095004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionin, V.V.; Kiselev, A.V.; Eliseev, N.N.; Mikhalevsky, V.A.; Pankov, M.A.; Lotin, A.A. Multilevel reversible laser-induced phase transitions in GeTe thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 117, 011901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlet, I.; Guerber, S.; Naoui, A.; Charbonnier, B.; Dupré, C.; Lugo-Alvarez, J.; Hellion, C.; Allain, M.; Podevin, F.; Perret, E.; et al. Optical Actuation Performance of Phase-Change RF Switches. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 2024, 45, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliseev, N.; Kiselev, A.; Ionin, V.; Mikhalevsky, V.; Burtsev, A.; Pankov, M.; Karimov, D.; Lotin, A. Wide range optical and electrical contrast modulation by laser-induced phase transitions in GeTe thin films. Results Phys. 2020, 19, 103466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevison, G.A.; Burrow, J.A.; Guo, H.; Sarangan, A.; Hendrickson, J.R.; Agha, I. Wavelength and power dependence on multilevel behavior of phase change materials. AIP Adv. 2021, 11, 85327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Thelander, E.; Gerlach, J.W.; Decker, U.; Zhu, B.; Rauschenbach, B. Single Pulse Laser-Induced Phase Transitions of PLD-Deposited Ge2Sb2Te5Films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 3621–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintersteller, S.; Yarema, O.; Kumaar, D.; Schenk, F.M.; Safonova, O.V.; Abdala, P.M.; Wood, V.; Yarema, M. Unravelling the amorphous structure and crystallization mechanism of GeTe phase change memory materials. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Lotnyk, A.; Ehrhardt, M.; Gerlach, J.W.; Rauschenbach, B. Realization of Multilevel States in Phase-Change Thin Films by Fast Laser Pulse Irradiation. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 5, 1700169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dun, A.; Wei, J.; Gan, F. Marangoni effect induced micro/nano-patterning on Sb2Te3 phase change thin film by laser pulse. Appl. Phys. A 2011, 103, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S.K.; Chopra, K.L. Amorphous Versus Crystalline GeTe Films. II. Optical Properties. J. Appl. Phys. 1969, 40, 4940–4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santala, M.K.; Reed, B.W.; Raoux, S.; Topuria, T.; LaGrange, T.; Campbell, G.H. Irreversible reactions studied with nanosecond transmission electron microscopy movies: Laser crystallization of phase change materials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 174105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevzorov, A.; Mikhalevsky, V.; Eliseev, N.; Kiselev, A.; Burtsev, A.; Ionin, V.; Maliutin, A.; Khmelenin, D.; Glebov, V.; Lotin, A. Two-stage conductivity switching of GST thin films induced by femtosecond laser radiation. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 157, 108773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastard, A.; Bastien, J.C.; Hyot, B.; Lhostis, S.; Mompiou, F.; Bonafos, C.; Servanton, G.; Borowiak, C.; Lorut, F.; Bicais-Lepinay, N.; et al. Crystallization study of “melt quenched” amorphous GeTe by transmission electron microscopy for phase change memory applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 243103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhang, D.; Shan, D.; Guo, B. Finite element simulation of temperature field in laser cleaning of TA15 titanium alloy oxide film. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2022, 52, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SiO2 | GeTe_a | GeTe_c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cp [J/(kg·K)] | 730 | 278 | 252 |

| Rho [kg/m3] | 2203 | 5600 | 5910 |

| Thermal conductivity [W/(m·K)] | 1.38 | 3.08 | 3.08 |

| Absorption coefficient [1/m] | 1 × 10−3 | 5.71 × 107 | 6.64 × 107 |

| Conductivity [S/m] | 0 | 0.64 | 3 × 105 |

| Relative dielectric constant | 4.2 | 18 | 18 |

| Transition temperature [K] | - | 473–673 | 998 |

| Erosion temperature | - | - | 1450 |

| Document | GeTe Thickness | Substrate | Laser Parameters | Crystallization | Amorphization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [23] | 75 nm | Si | 248 nm, 20 ns, pump-probe setup | 26 mJ/cm2, 5 pulses | 112 mJ/cm2 |

| [25] | 60 nm | Si | 248 nm, 20 ns, pump-probe setup | 11–14 mJ/cm2 >5 pulses | 162–182 mJ/cm2 |

| [12] | 200 nm | Al2O3 | 248 nm, 30 ns, a KrF excimer laser | 90 mJ/cm2 | 180 mJ/cm2 |

| [17] | 100 nm | SiO2 | 532 nm, 13 ns, Top hat | 47.6 mJ/cm2 | 70 mJ/cm2 |

| This work | 150 nm | SiO2 | 532 nm, 10 ns, Gaussian | 8.5–15 mJ/cm2 | 25.4 mJ/cm2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, Q.; Qian, S.; Jiang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Fu, Y. Phase Transition Behavior and Threshold Characteristics of GeTe Thin Films Under Single-Pulse Nanosecond Laser Irradiation. Materials 2025, 18, 5466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235466

Li Y, Ma X, Chen Q, Qian S, Jiang Y, Zheng Y, Fu Y. Phase Transition Behavior and Threshold Characteristics of GeTe Thin Films Under Single-Pulse Nanosecond Laser Irradiation. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235466

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yajing, Xinyu Ma, Qiang Chen, Sixian Qian, Yixuan Jiang, Yuejun Zheng, and Yunqi Fu. 2025. "Phase Transition Behavior and Threshold Characteristics of GeTe Thin Films Under Single-Pulse Nanosecond Laser Irradiation" Materials 18, no. 23: 5466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235466

APA StyleLi, Y., Ma, X., Chen, Q., Qian, S., Jiang, Y., Zheng, Y., & Fu, Y. (2025). Phase Transition Behavior and Threshold Characteristics of GeTe Thin Films Under Single-Pulse Nanosecond Laser Irradiation. Materials, 18(23), 5466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235466