Analysis of Superjunction MOSFET (CoolMOS™) Concept Limitations—Part I: Theory

Abstract

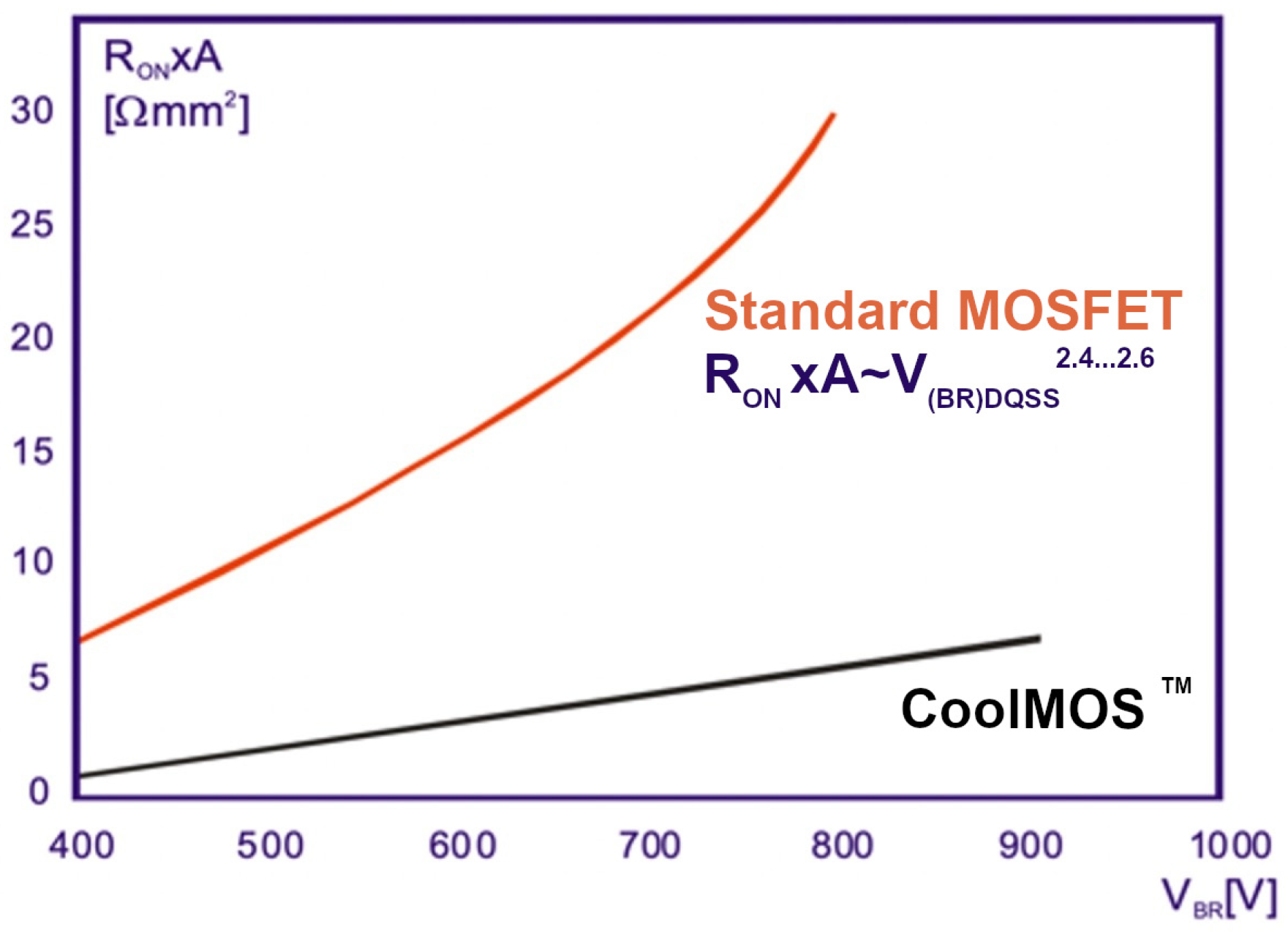

1. Introduction

2. Materials

2.1. Superjunction Origin

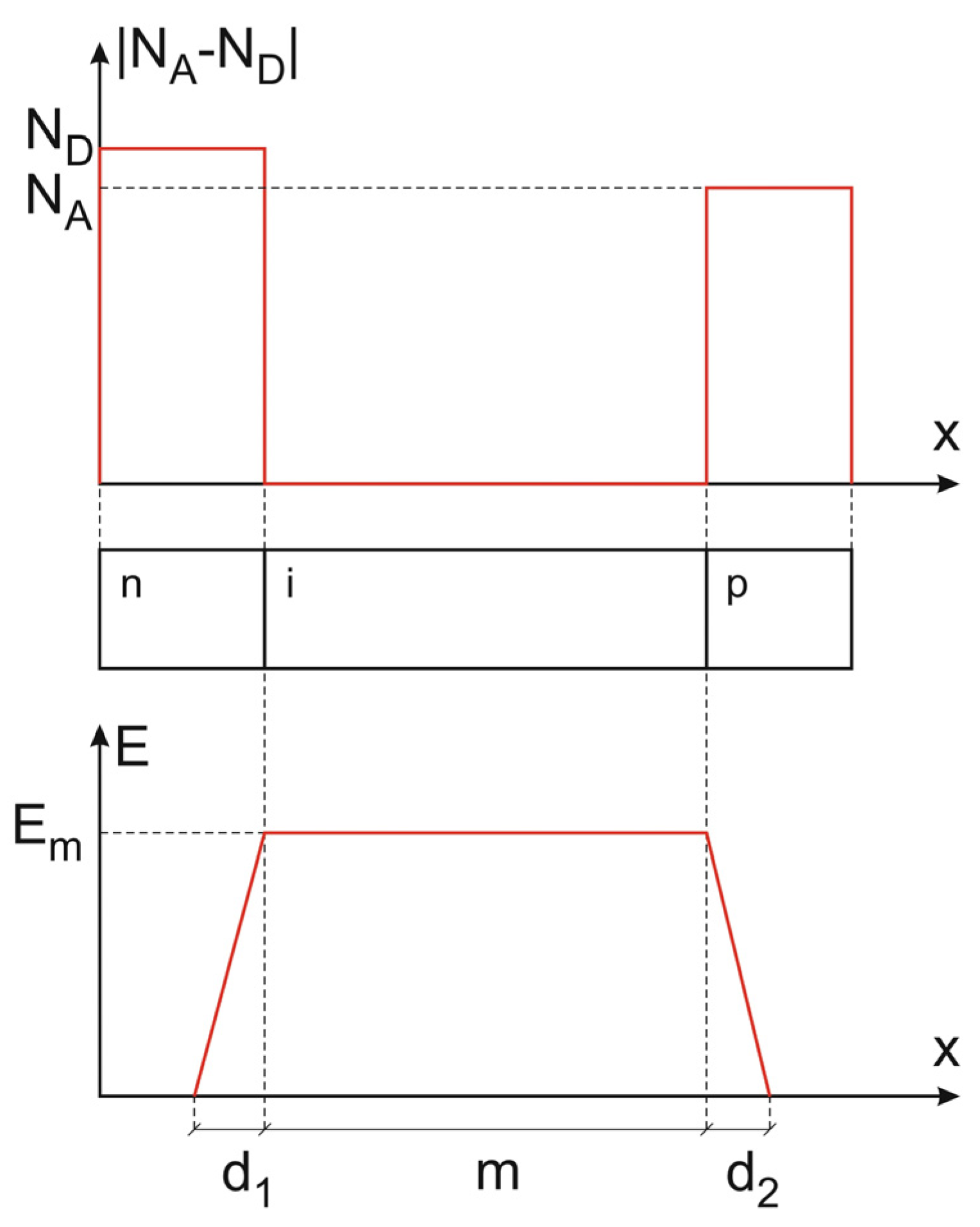

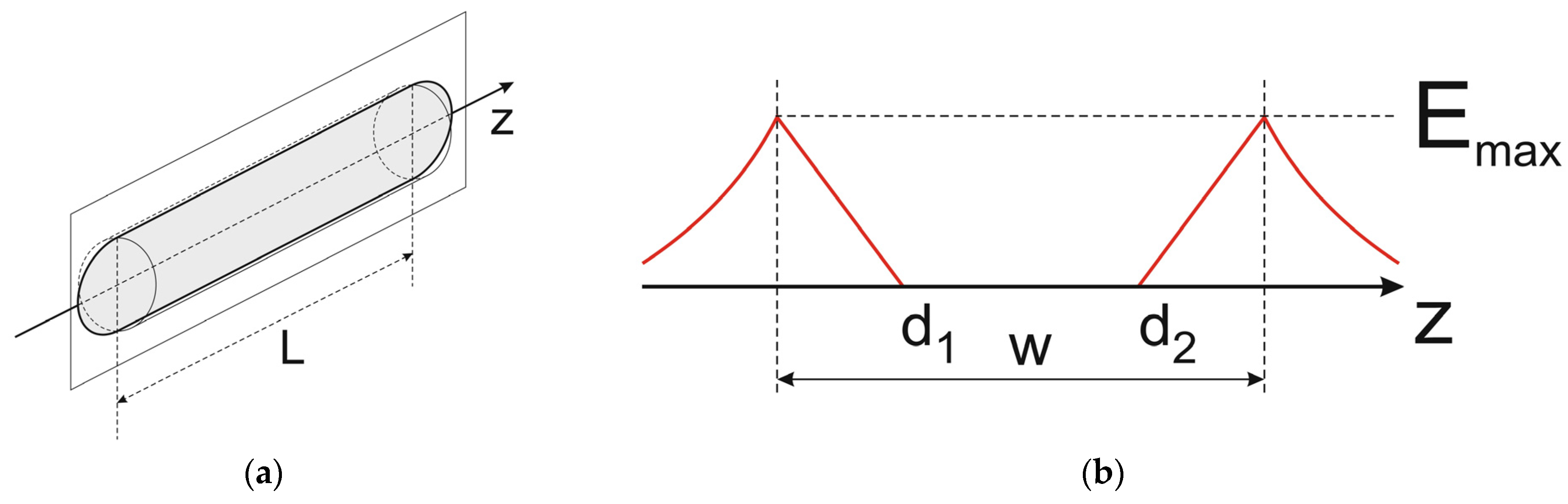

2.1.1. Built-In Charge Flat Field Domain (bcFFD)

2.1.2. Doped Semiconductor Flat Field Domain (dsFFD)

2.2. Superjunction Diode

2.2.1. Reverse Bias Ability

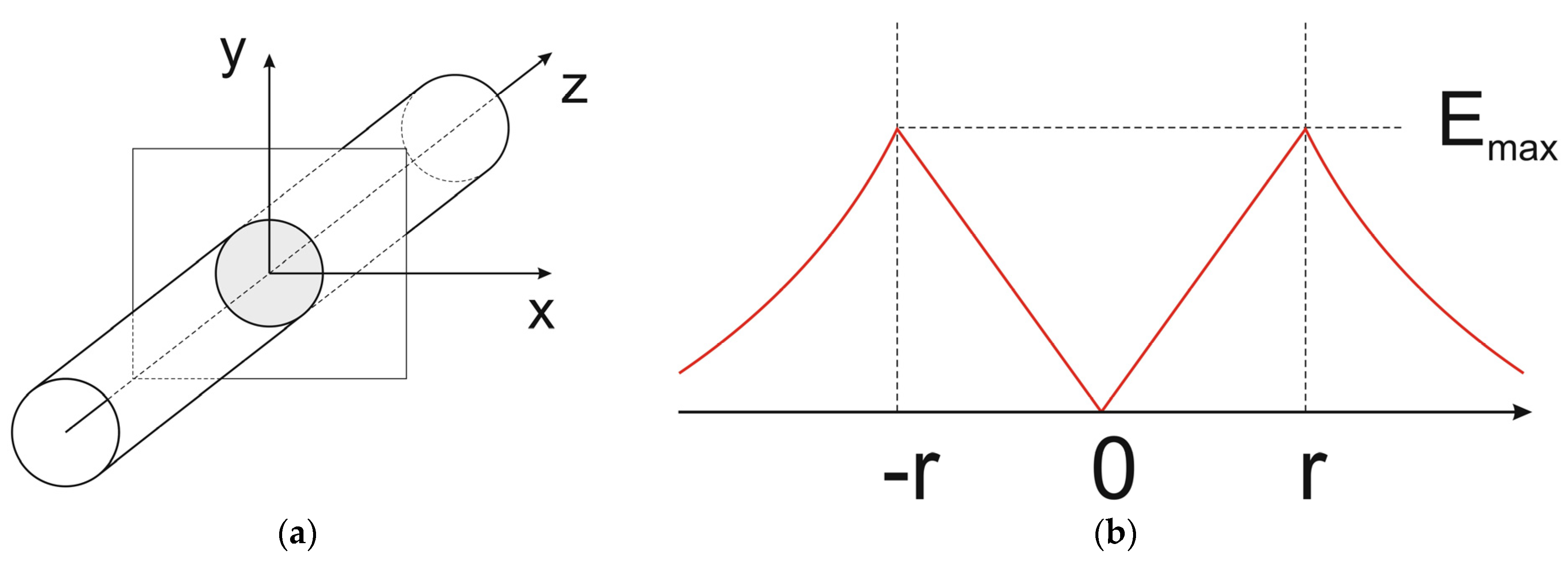

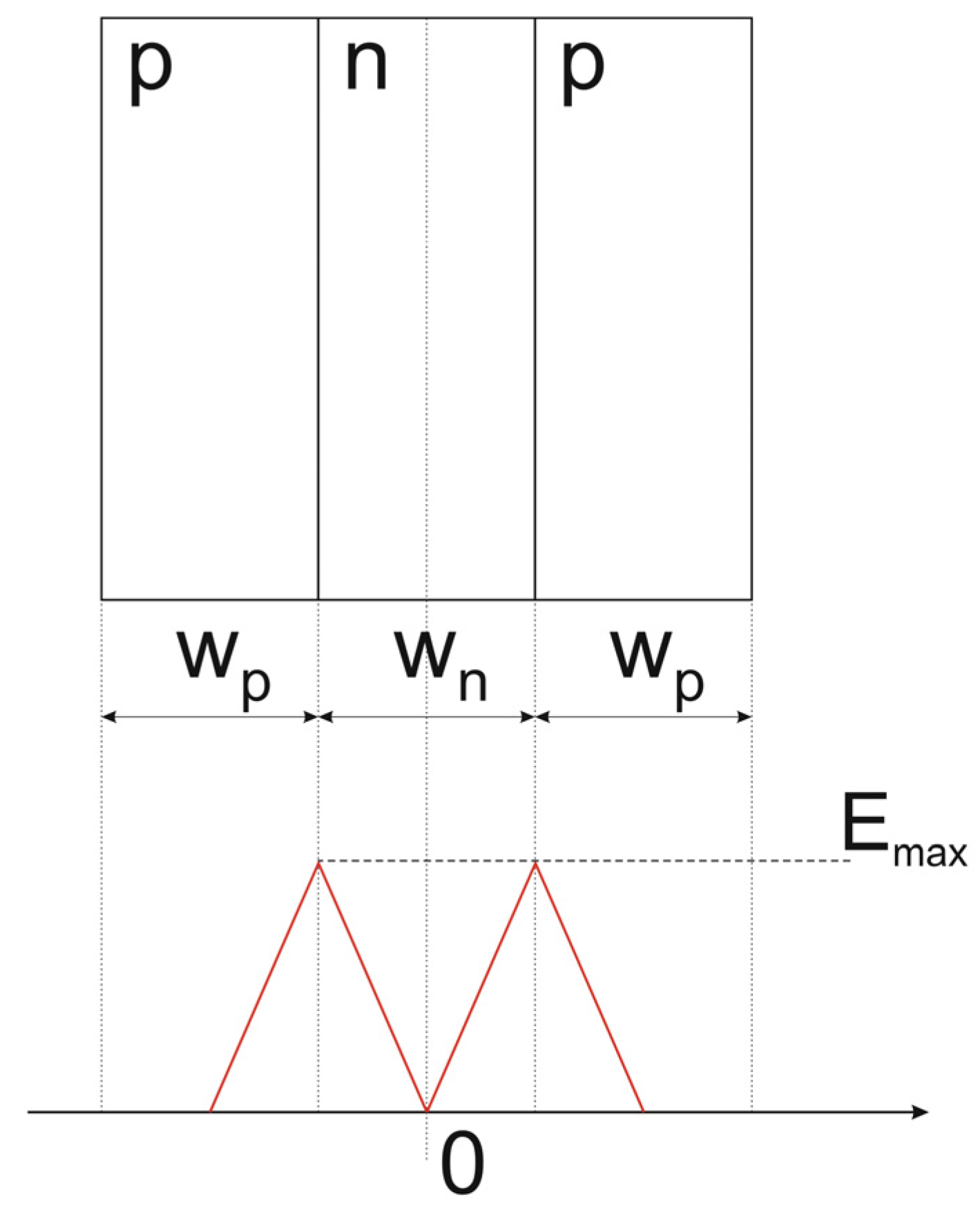

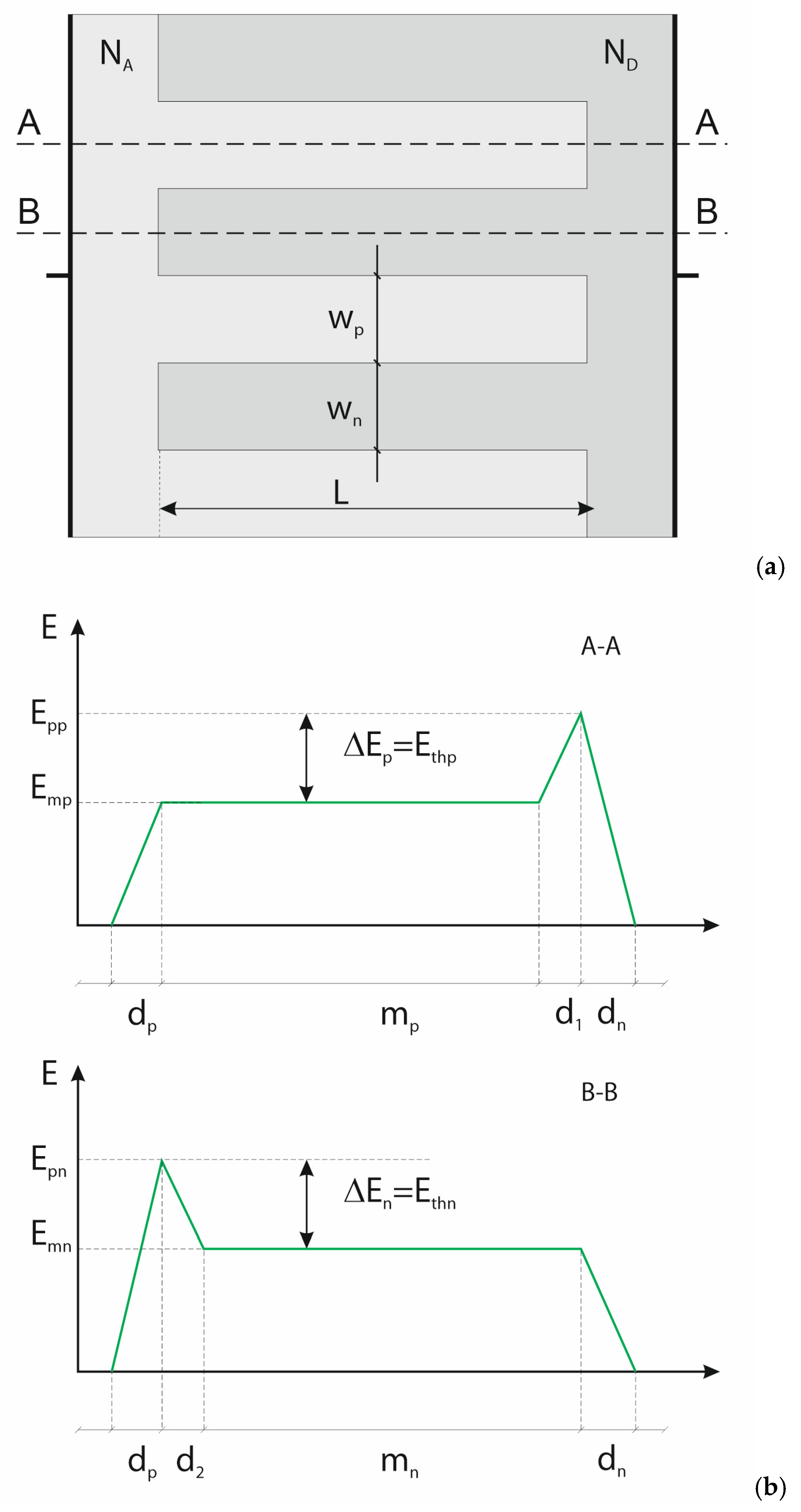

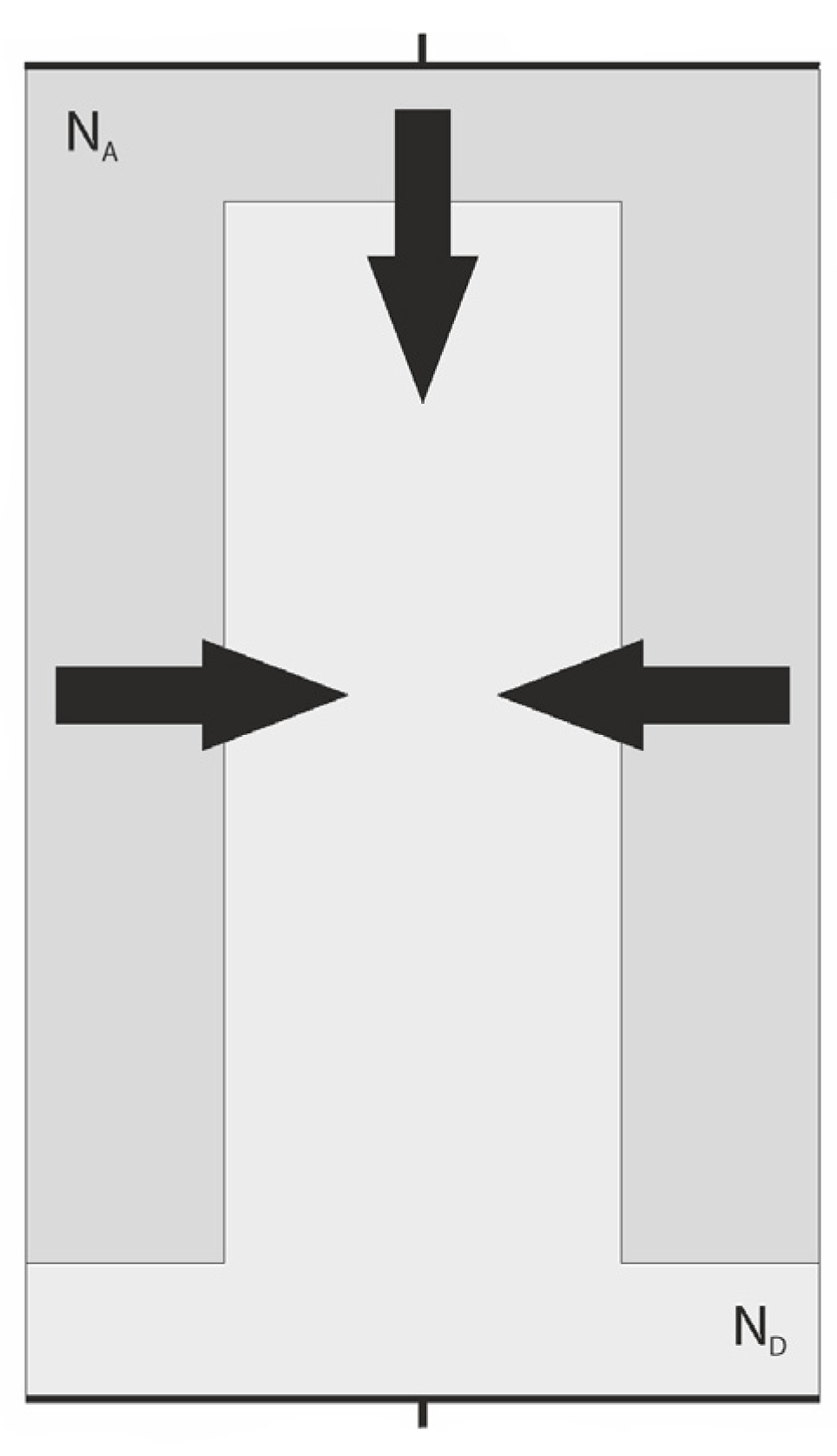

- Comparing (6), (7), and (1), one can notice that they are almost identical. They describe the same FFD phenomenon taking place in the diodes corresponding to p- and n-pillars of the superjunction diode in Figure 7 and the ideal p-i-n diode in Figure 3. Its presence leads to devices with generally unlimited blocking voltage. In the case of diodes corresponding to pillars in Figure 7, they can be formally considered as separate devices, although eventually they are aggregated into one device, which results in the identical length L and the identical maximal electrical field strength Epp = Epn. In the paper, the p-pillar diode is considered the main one, and next, the results are extended to the n-pillar diode.

- According to (6) and (7), the reverse voltage drops, VSJp and VSJn, increase with the increase of mn and mp, whereas the maximum electric fields, Epp and Epn remain unchanged. For a symmetrical superjunction, in which NA = ND, one can simplify Equations (6) and (7), taking into account that d1 = d2, and mn = mp = m. Now they become identical: VSJp = VSJn = VSJ.

- In the parallel pillar connection, the relation VSJn = VSJp must be kept at all times. Since the electric field strength on the junction plane is constant, the relation Epp = Epn is fulfilled. To obtain Ethn = Ethp = Eth, the construction of the diode must ensure that the dsFFD areas come out in both the pillars at the same bias.

- In the pillars, the avalanche breakdown occurs when the maximum electric field, Epp or Epn, reaches the local critical magnitude Ecritp or Ecritn, which may locally differ, e.g., due to the changes in dopant concentration, as it is shown in Figure 8. So, the breakdown voltage for p- or n-pillar is:

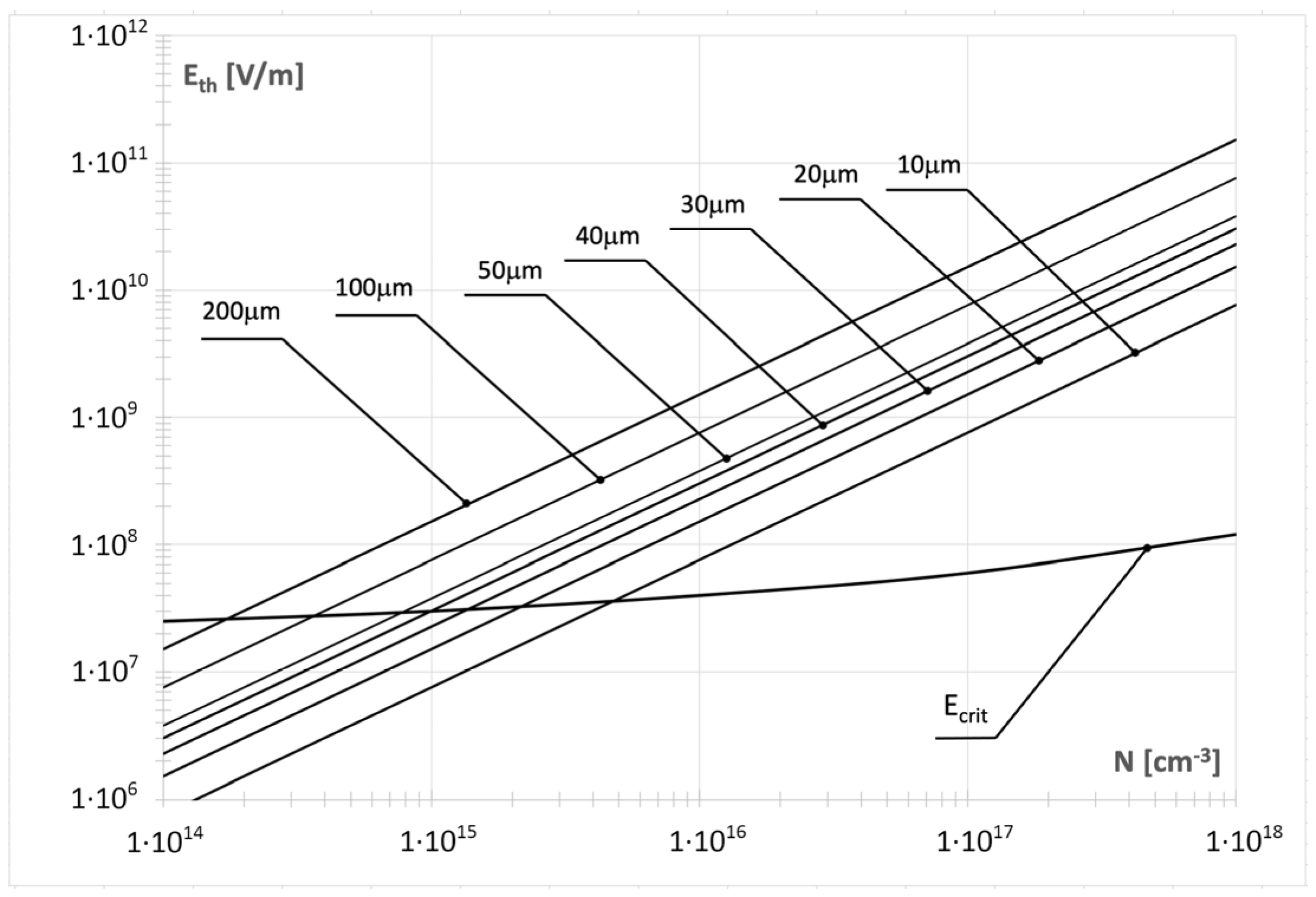

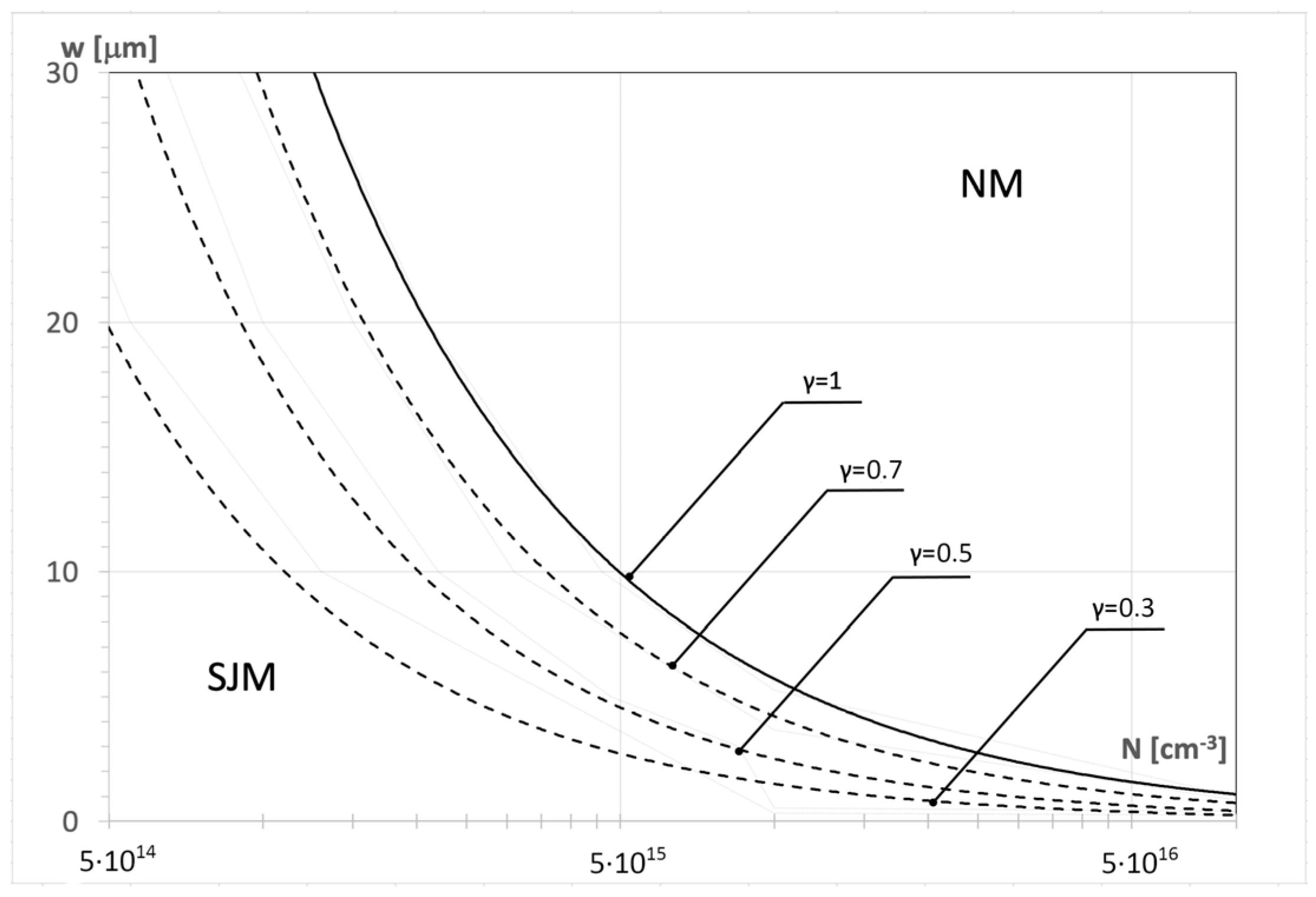

- The first element of Relations (8) and (9) corresponds to the breakdown voltage of a planar p-n junction, whereas the second one represents the complementary component introduced by the superjunction effect. It does not occur when Eth ≥ Ecrit, and the breakdown voltage is defined by the doping concentrations, NA and ND only. The superjunction component in (8) and (9) can be presented generally as:where γ = Eth/Ecrit ∈ <0;1>—the superjunction coefficient.

- Introducing ∆Ep = Eth < Ecritp into (5), one can obtain the design condition ensuring the presence of the superjunction effect in the p-pillar:

- Similar consideration performed for the n-pillar will result in a similar design condition, ensuring the presence of the superjunction effect in the n-pillar:

- In Figure 7, the superjunction is formed as a parallel connection of several p- and n-pillars with their own breakdown voltages, VBp and VBn, respectively. Generally, they may be different when Ecritn ≠ Ecritp and the total superjunction breakdown voltage is equal to the lower pillar breakdown voltage VBp or VBn.

- In each pillar, the product N,w must correspond to a point inside the SJM region in Figure 9 to allow FFD areas to be built in.

- The junction planes separating pillars must be parallel to ensure the flatness of the electric field inside the FFD areas.

- To ensure the simultaneous development of the identical reverse voltage drop in the separated pillars, the magnitude of the electric field strength on the junction plane must be the same. It also concerns the threshold electric field Ethn, which, taking advantage of (13), leads to the restriction:

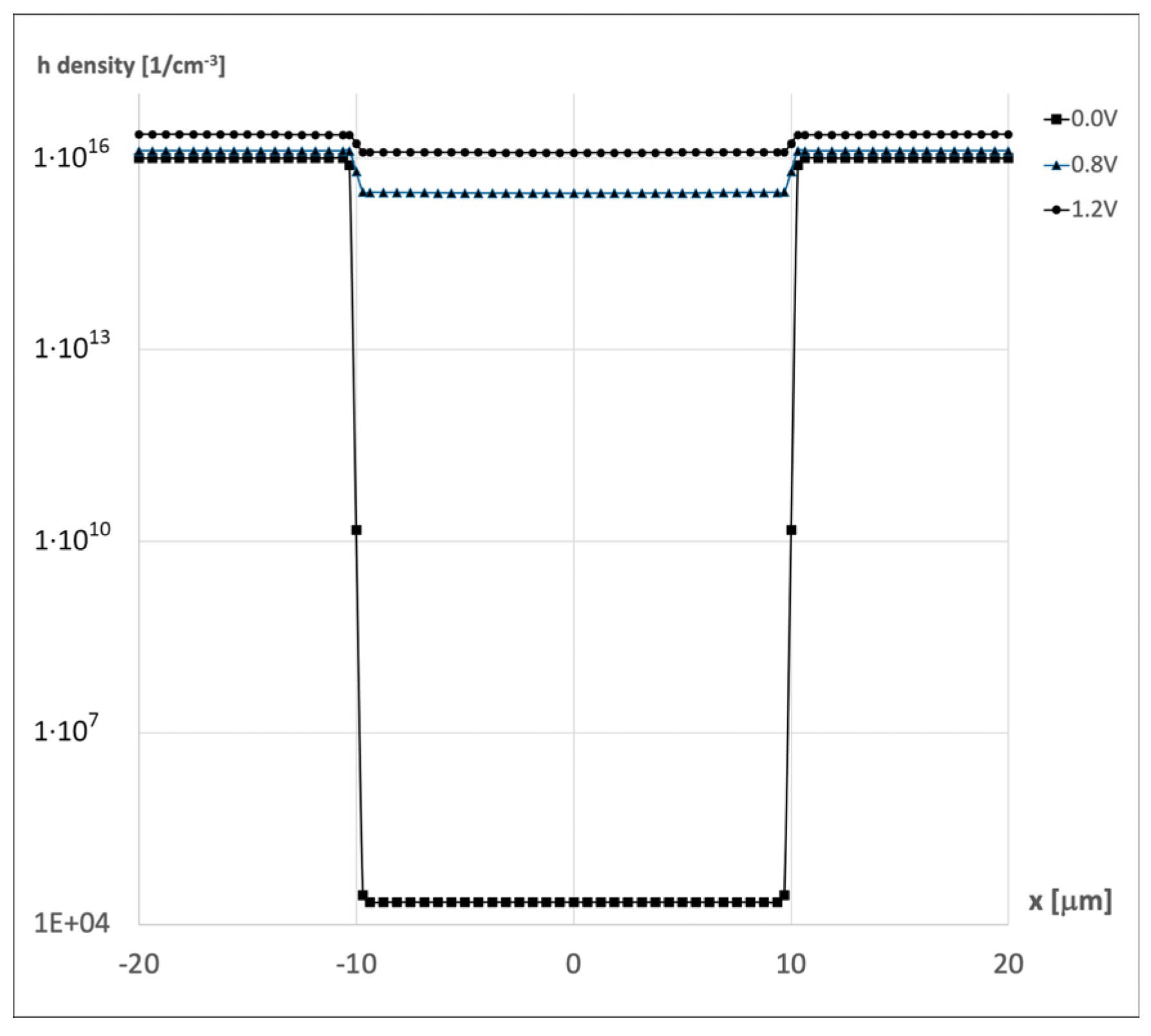

2.2.2. Forward Bias Conditions

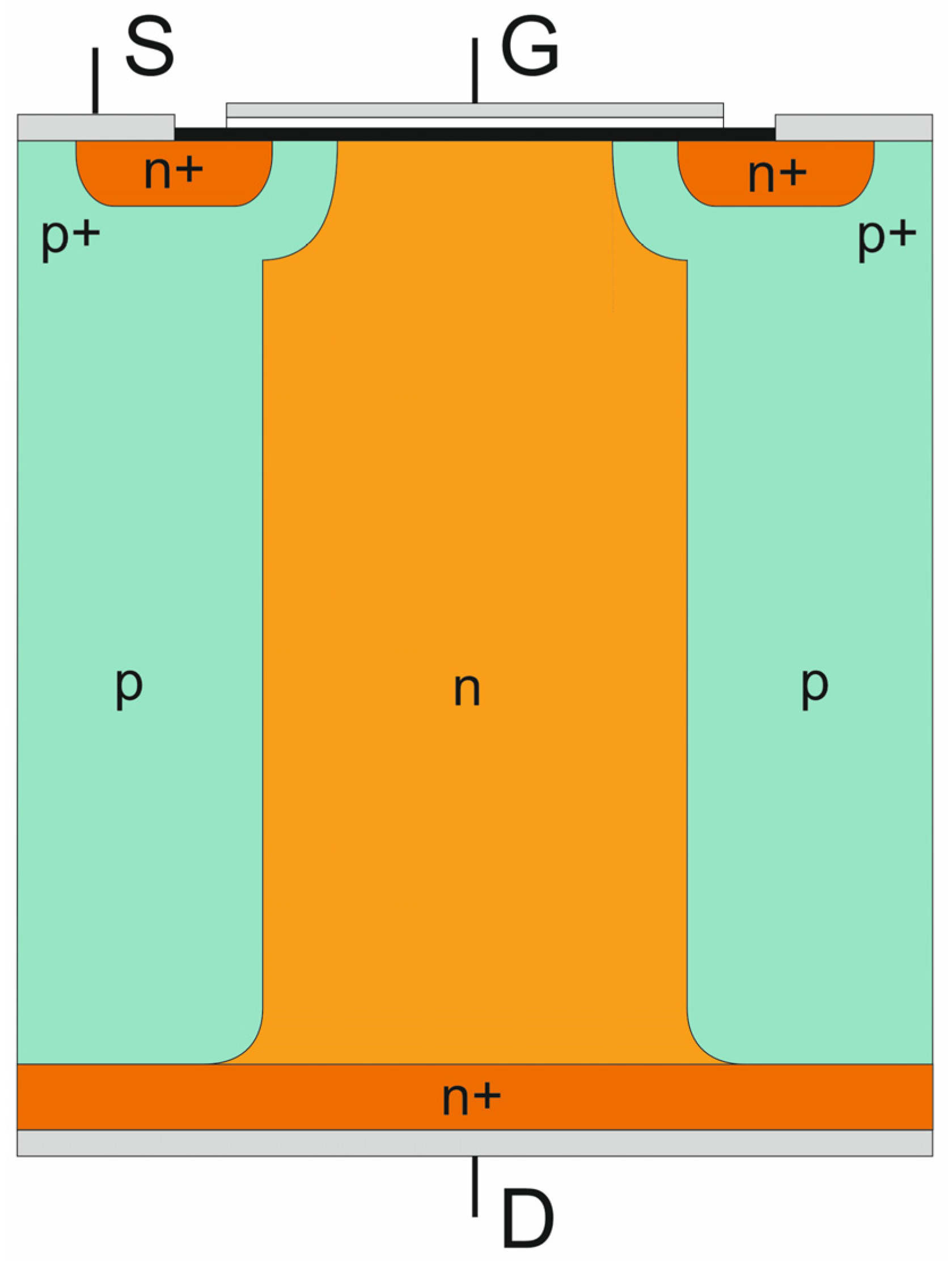

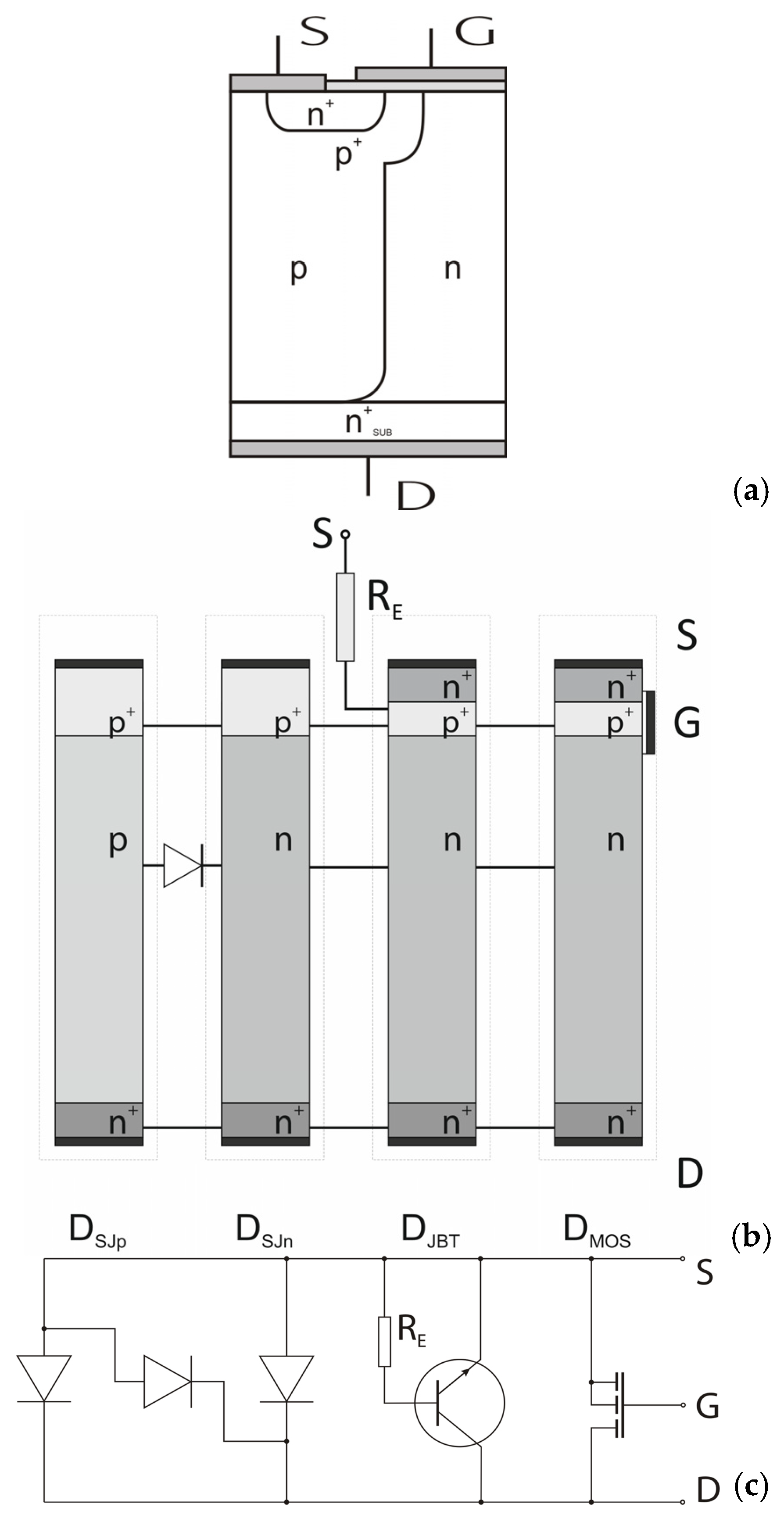

2.3. Superjunction CoolMOS™ Transistor

- The CoolMOS™ forward current flows in the section DMOS only, which reduces the effective area of current flow to the n-pillar;

- The CoolMOS™ breakdown voltage is limited to its lowest magnitude occurring in the section DJBT and is determined by Relation (15);

- The first component of Relation (15) represents the breakdown of the planar p-n junction and is limited by the Ecrit, whereas the second one represents the superjunction effect and has no physical limits, and it is decisive mainly for the final breakdown voltage of CoolMOS™. Therefore, for simplicity, the Relation (15) can be reduced to the second component only:

3. Discussion

- The superjunction diode constitutes a parallel connection of several p- and n-pillars with their own breakdown voltages.

- The pillars’ junction planes need to be parallel to ensure the electric field remains uniform throughout the FFD regions.

- The proper work of the SJ diode requires the symmetry in the pillars design that should fulfill Condition (14).

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | |

| SJ | SuperJunction |

| SJM | SuperJunction Mode |

| NM | Normal Mode |

| NA, ND | doping concentration in the p- and n-layer |

| E, Ecrit, Eth | electric field, critical electric field, threshold electric field |

| VSJ | reverse voltage drops in superjunction |

| VB, RON | breakdown voltage, on-resistance |

| wp, wn | a and n column width |

| Symbols | |

| α | bipolar transistor coefficient |

| γ | superjunction coefficient |

References

- Fujihira, T. Theory of semiconductor superjunction devices. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1997, 36, 6254–6262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.B.; Mawby, P.A.; Board, K.; Salama, C.A.T. Theory of novel voltage-sustaining layer for power devices. Microelectron. J. 1998, 29, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, L.; Maerz, M.; Deboy, G. CoolMOS—An important milestone towards a new power MOSFET generation. In Proceedings of the 38th International Power Conversion Conference PCIM’98, Nuremberg, Germany, 26–28 May 1998; pp. 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, L.; Deboy, G.; Knapp, A.; Marz, M. CoolMOS—A new milestone in high voltage power MOS. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs ISPSD’99, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26–28 May 1999; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strollo, A.G.; Napoli, E. Power superjunction devices: An analytic model for breakdown voltage. Microelectron. J. 2001, 32, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strollo, A.G.; Napoli, E. Optimal on-resistance versus breakdown voltage tradeoff in superjunction power devices: A novel analytical model. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2001, 48, 2161–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondekar, P.; Patil, M.; Parikh, C. Analysis and design of super junction power MOSFET: CoolMOS for improved on resistance and breakdown voltage using theory of novel voltage sustaining layer. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Microelectronics, Nis, Serbia, 12–15 May 2002; pp. 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgórski, J. Analysis of New Structures of Unipolar Power Semiconductor Devices. Ph.D. Thesis, Lodz University of Technology, Lodz, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Podgórski, J.; Lisik, Z. Numerical investigation of the CoolMOS features. In Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications EPE’2003, Toulouse, France, 2–4 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, T.; Khemka, V.; Qin, G.; Zitouni, M.; Gupta, R. Modeling and analysis of 3-D core-shell superjunction structures. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2020, 68, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akshay, K.; Karmalkar, S. Optimum aspect ratio of superjunction pillars considering charge imbalance. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2021, 68, 1798–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, B.J.; Parikh, C.D.; Patil, M.B. Modeling of the CoolMOS transistor. II. DC model and parameter extraction. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2002, 49, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Udrea, F. True material limit of power devices—Applied to 2D superjunction MOSFET. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2018, 65, 1432–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, M.; Lisik, Z.; Podgórski, J. Numerical simulation of CoolMOS transistor, in Experience of Designing and Applications of CAD Systems in Microelectronics. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference CADSM 2001, Lviv-Slavsko, Ukraine, 12–17 February 2001; pp. 303–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisik, Z.; Podgórski, J.; Raj, E. Numerical evaluation of the influence of technology incorrectness on CoolMOS features. In Proceedings of the International Conference Modern Problems of Radio Engineering, Telecommunications and Computer Science, Lviv-Slavsko, Ukraine, 24–28 February 2004; pp. 565–567. [Google Scholar]

- Fujihira, T.; Miyasaka, Y. Simulated superior performances of semiconductor superjunction devices. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs ISPSD’98, Kyoto, Japan, 3–6 June 1998; pp. 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Hu, K.; Xu, W.; Xu, S.; Cui, W.; Zhang, W.; Ng, W.T. Numerical solutions for electric field lines and breakdown voltages in superjunction—Like power devices. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2020, 67, 3898–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, W.; Omura, I.; Aida, S.; Koduki, S.; Izumisawa, M.; Yoshioka, H.; Okumura, H.; Yamaguchi, M.; Ogura, T. A 15.5 m Ω cm2-680V superjunction MOSFET reduced on-resistance by lateral pitch narrowing. In Proceedings of the 18th International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs ISPSD’06, Naples, Italy, 4–8 June 2006; pp. 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, J.; Noda, Y.; Shibata, T.; Nogami, S.; Yamaoka, T.; Yamaguchi, H. 600V-class super junction MOSFET with high aspect ratio P/N columns structure. In Proceedings of the 20th International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs ISPSD’08, Orlando, FL, USA, 18–22 May 2008; pp. 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugi, A.; Takei, M.; Takahashi, K.; Yajima, A.; Tomizawa, H.; Nakazawa, H. Super junction MOSFETs above 600V with parallel gate structure fabricated by deep trench etching and epitaxial growth. In Proceedings of the 20th International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs ISPSD’08, Orlando, FL, USA, 18–22 May 2008; pp. 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecino, E.; Stückler, F.; Pippan, M.; Hancock, J. First generation of 650V super junction devices with RDS(on)*A values below 1 Ω*mm2-best efficiency that keeps the ease-of-use and enables higher power ratings and frequencies. In Proceedings of the International Exhibition & Conference for Power Electronics. Intelligent Motion, Renewable Energy and Energy Management PCIM Europe’13, Nuremberg, Germany, 14–16 May 2013; pp. 621–628. [Google Scholar]

- Udrea, F.; Deboy, G.; Fujihira, T. Superjunction power devices, History, Development and Future Prospects. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2017, 64, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synopsys. Sentaurus Manual; Synopsys, Inc.: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan, K.; Guan, L.; Bobde, M.; Lui, S.; Bhalla, A.; Yilmaz, H.; Zhang, L. Self terminating lateral-vertical hybrid super-junction FET that breaks RDS·A—Charge balance trade-off window. In Proceedings of the IEEE 30th International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs ISPSD’18, Chicago, IL, USA, 13–17 May 2018; pp. 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, S.M.; Li, Y.; Ng, K.K. Physics of Semiconductor Devices, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lisik, Z.; Podgórski, J. On-resistance modulation in Super Junction Diode. In Proceedings of the 14th Conference on Electron Technology—ELTE 2023, Ryn, Poland, 18–21 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lisik, Z.; Podgórski, J. Analysis of Superjunction MOSFET (CoolMOS™) Concept Limitations—Part I: Theory. Materials 2025, 18, 5451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235451

Lisik Z, Podgórski J. Analysis of Superjunction MOSFET (CoolMOS™) Concept Limitations—Part I: Theory. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235451

Chicago/Turabian StyleLisik, Zbigniew, and Jacek Podgórski. 2025. "Analysis of Superjunction MOSFET (CoolMOS™) Concept Limitations—Part I: Theory" Materials 18, no. 23: 5451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235451

APA StyleLisik, Z., & Podgórski, J. (2025). Analysis of Superjunction MOSFET (CoolMOS™) Concept Limitations—Part I: Theory. Materials, 18(23), 5451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235451