On the Heterogeneity of Deformation and Fracture in Bimetallic Specimens of the C11000-Inconel 625 System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

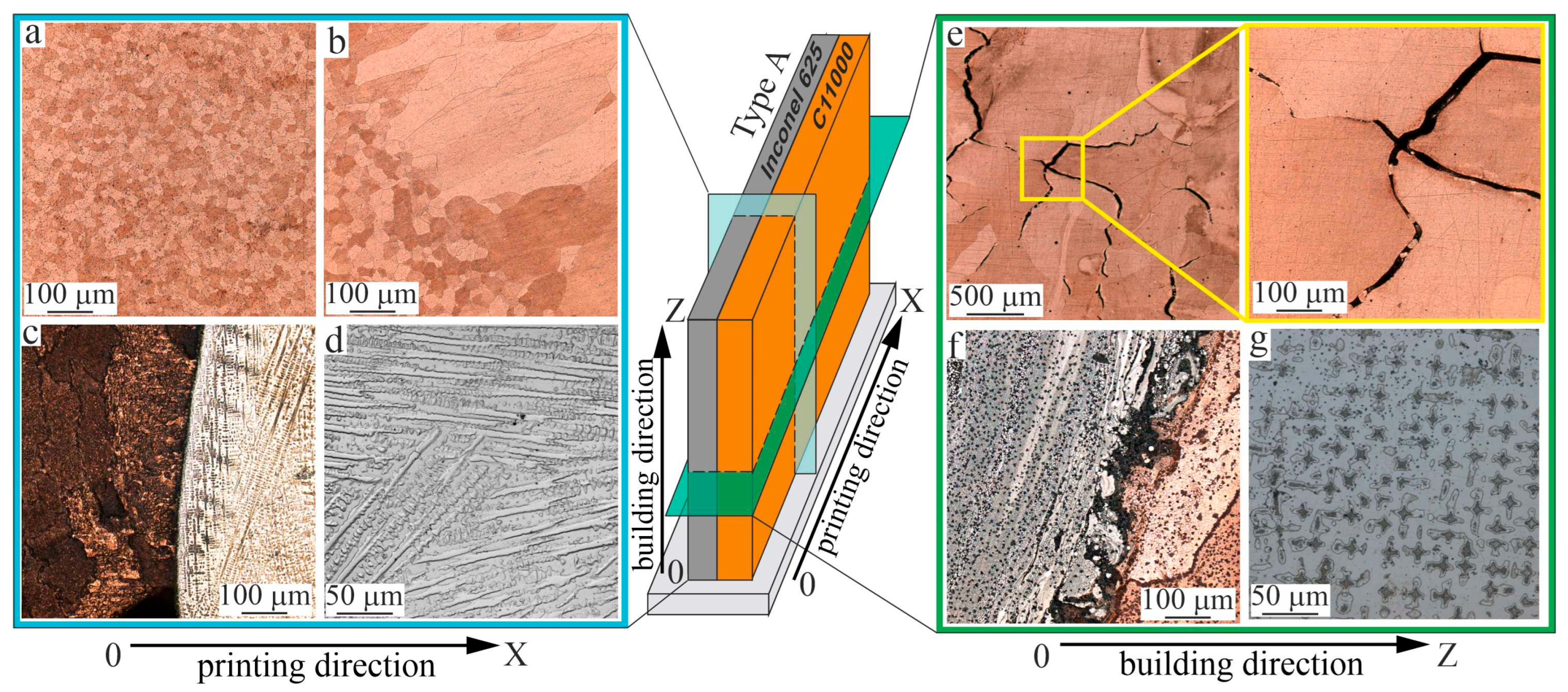

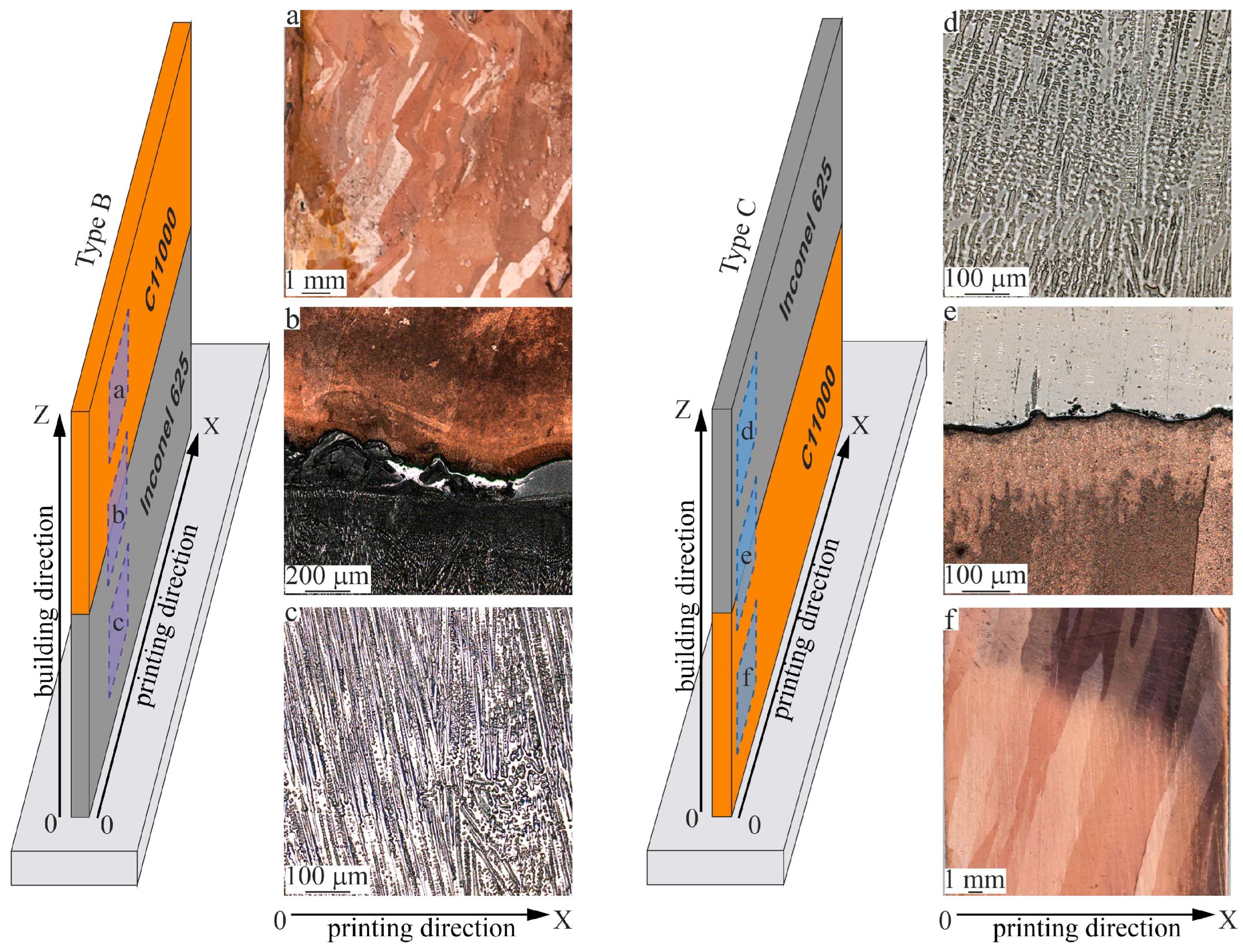

3.1. Macrostructure of C11000-Inconel 625 Bimetallic Specimens of Types A, B, and C

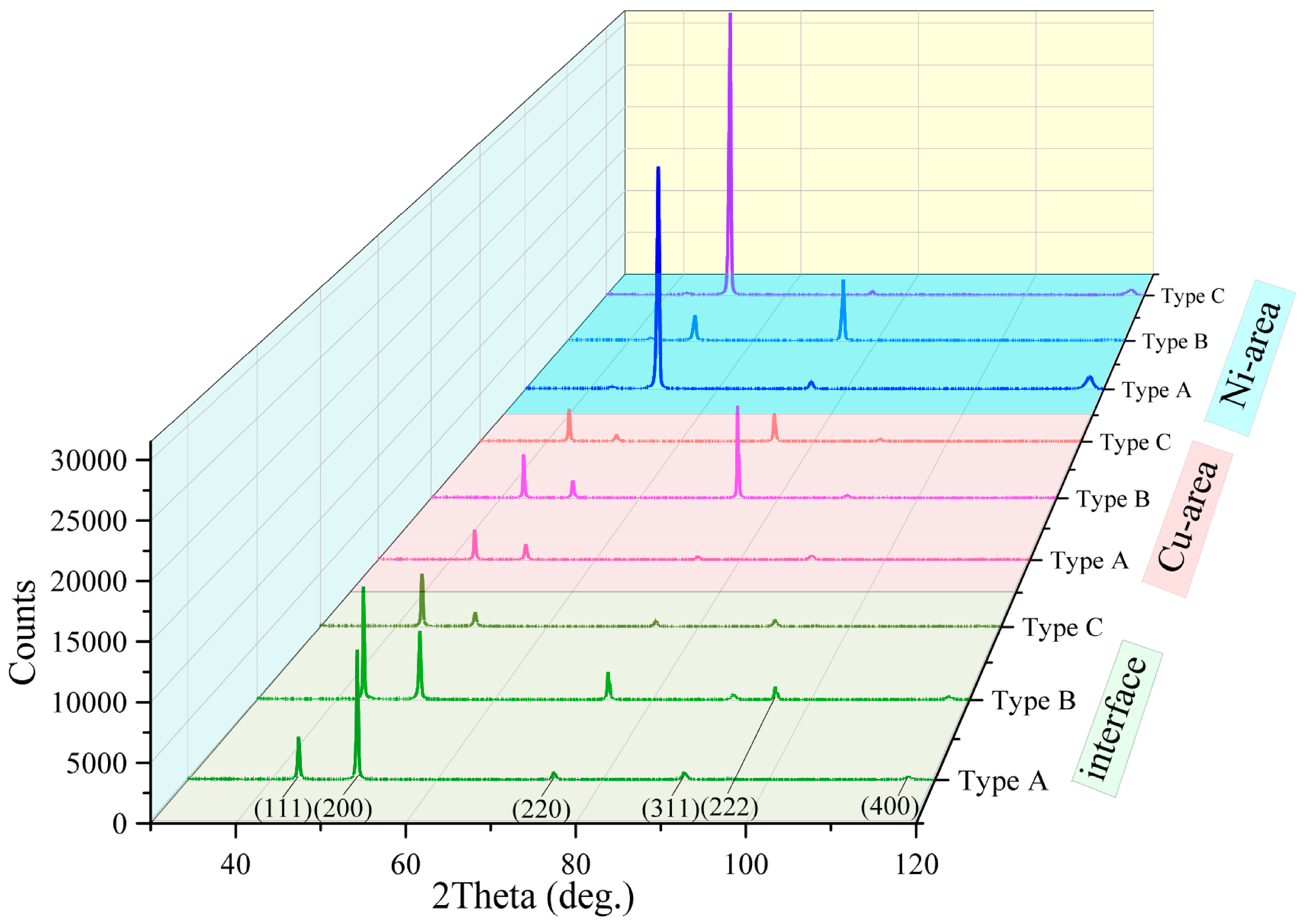

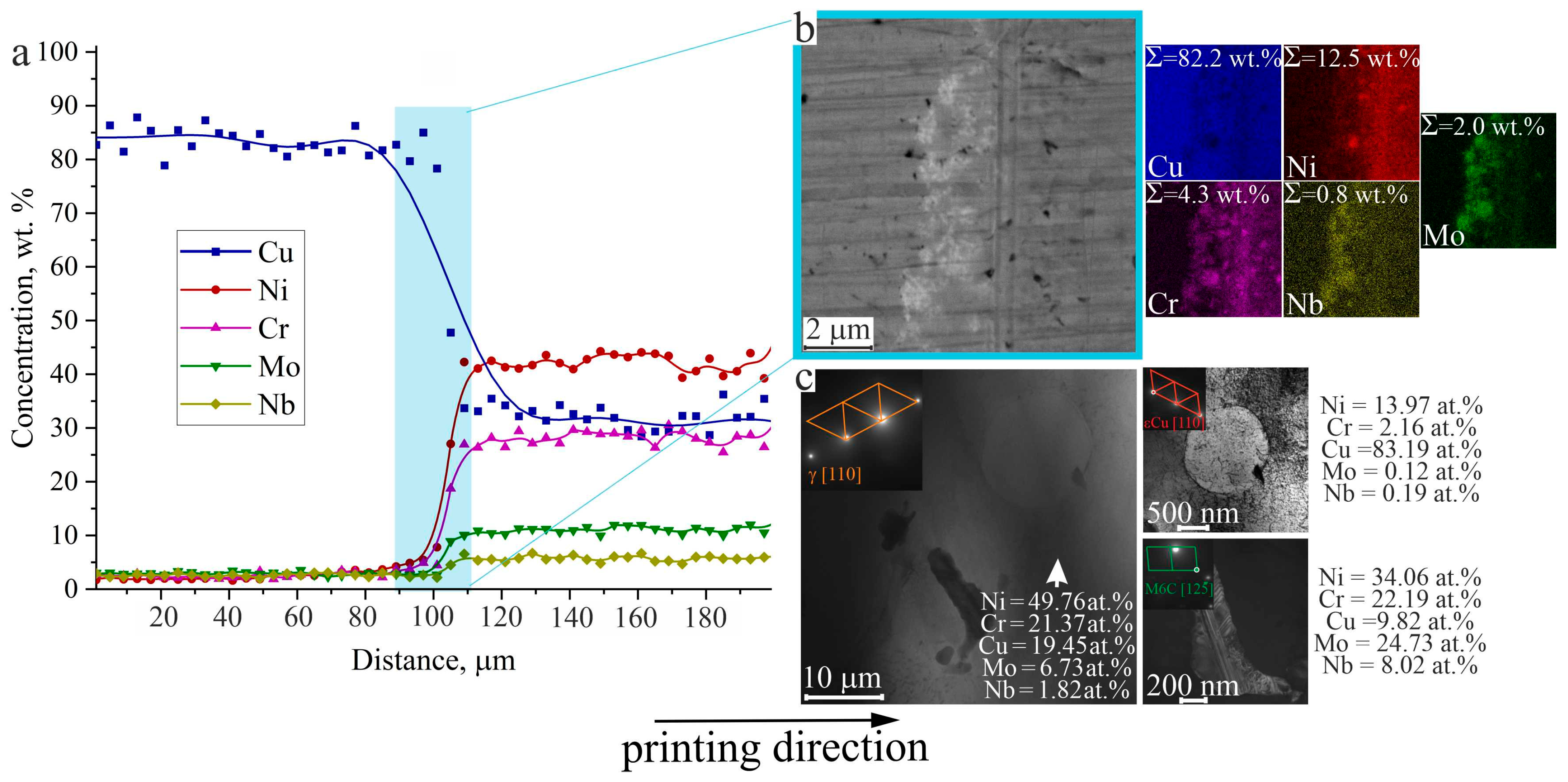

3.2. Structural and Phase State Analysis of Bimetallic Specimens of Copper C11000-Inconel 625 Types A, B, and C

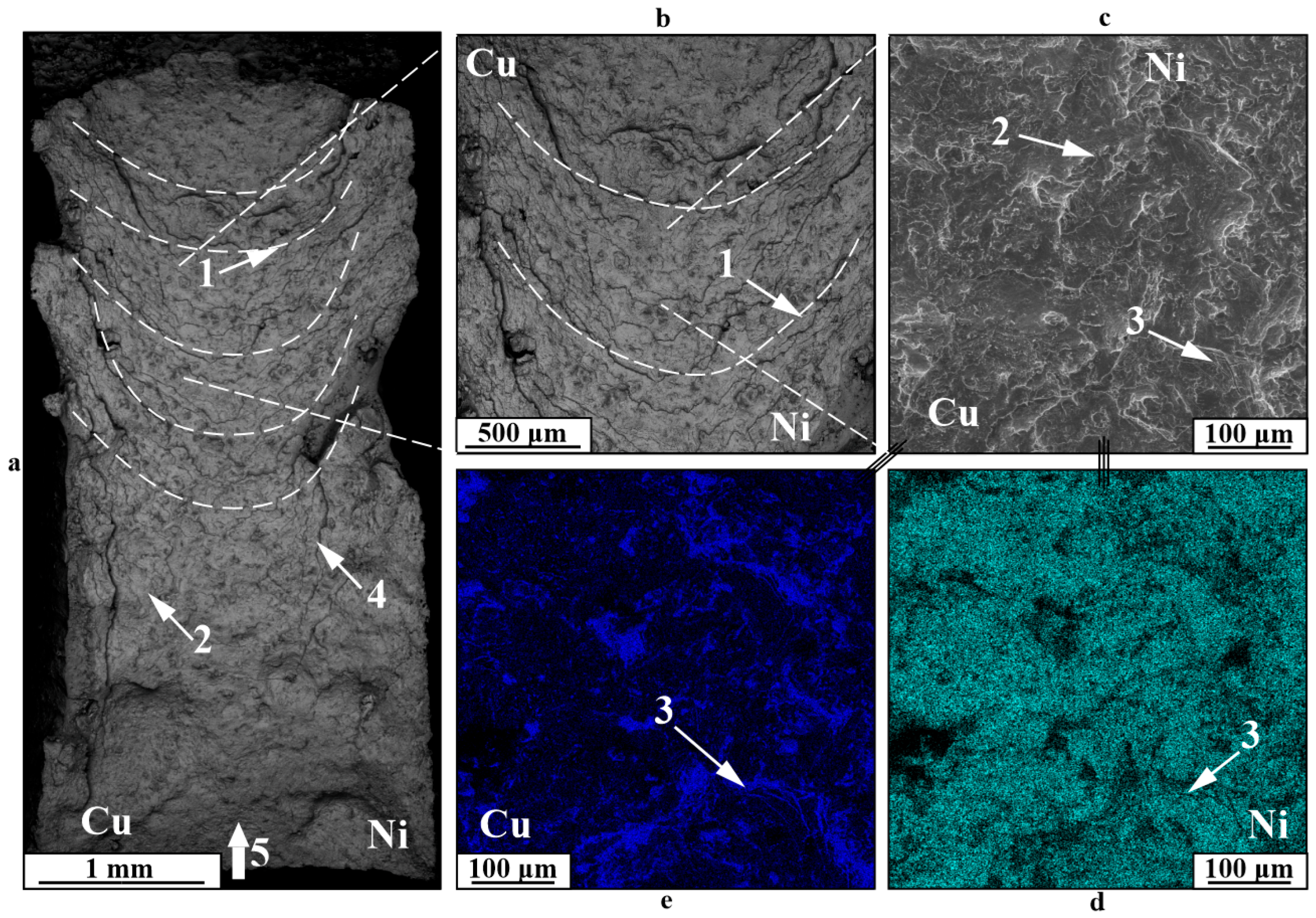

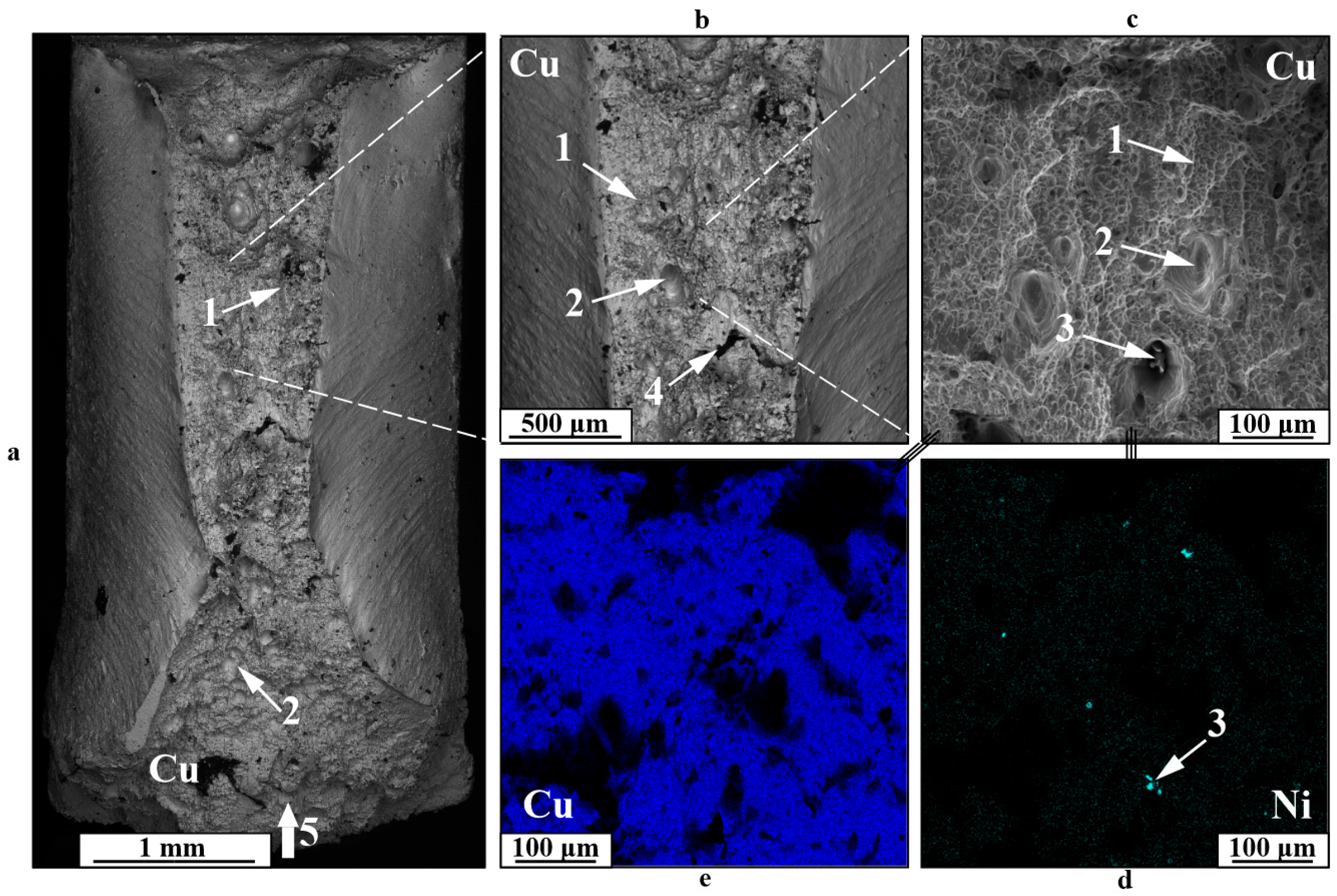

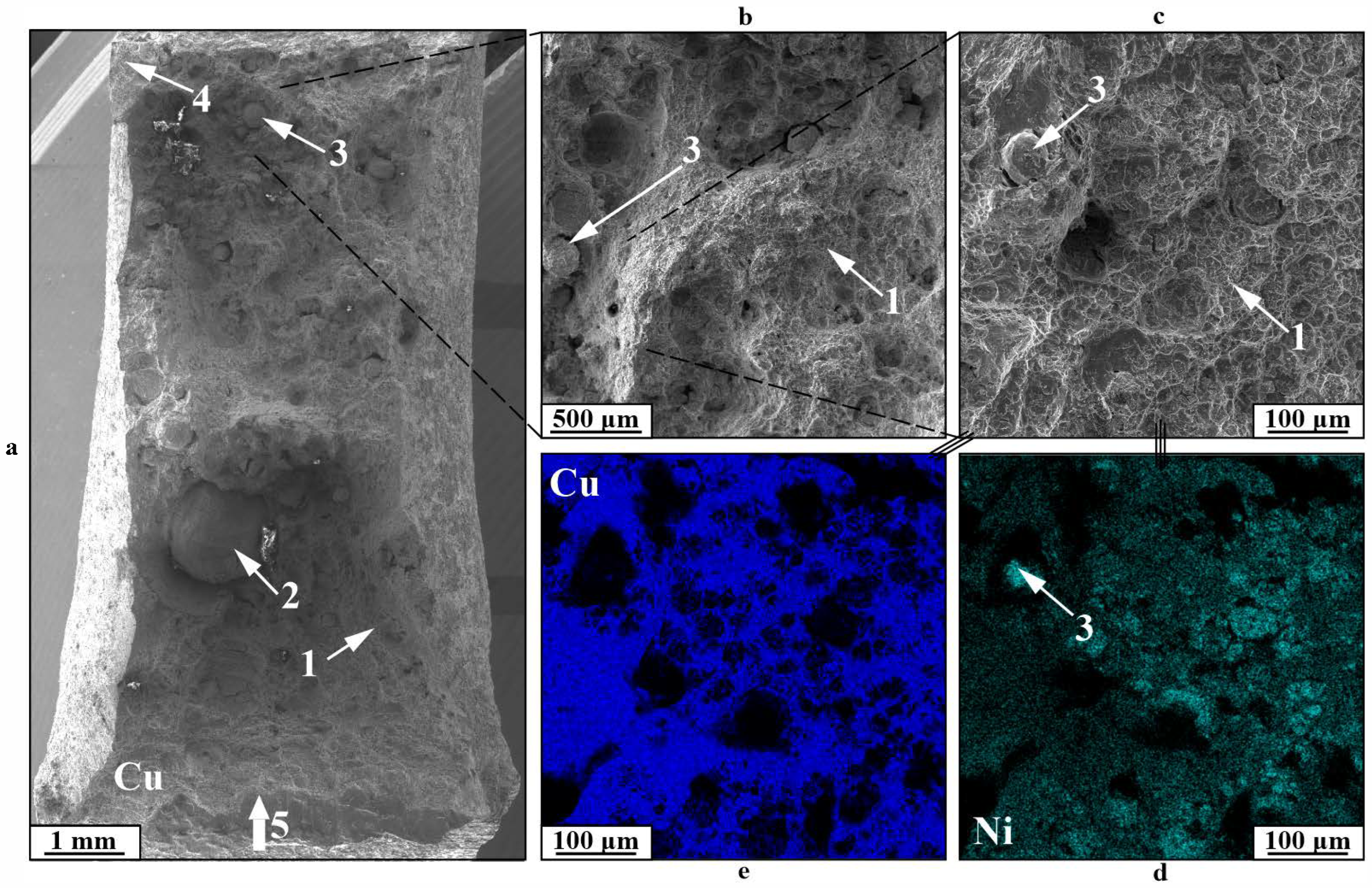

3.3. Mechanical Properties and Fractography of the Bimetallic Specimens C11000-Inconel 625 of Types A, B, and C

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thirunavukarasu, G.; Chatterjee, S.; Kundu, S. Scope for improved properties of dissimilar joints of ferrous and non-ferrous metals. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2017, 27, 1517–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Li, B. A bimodal and heterogeneous laminate structure with alternately distributed copper-base and nickel-base alloys via multi-material laser powder bed fusion (MM-LPBF) additive manufacturing. Mater. Lett. 2024, 377, 137494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenych, O.; Kostryzhev, A. Strengthening mechanisms in nickel-copper alloys: A review. Metals 2020, 10, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.; Zhang, G. New process for integrated manufacturing of copper alloy shells by bimetal 3D printing remanufacturing technology. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 11052–11063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamunya, Y.E.P.; Davydenko, V.V.; Pissis, P.; Lebedev, E.V. Electrical and thermal conductivity of polymers filled with metal powders. Eur. Polym. J. 2002, 38, 1887–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.H.; Zhang, X.M.; Ding, H. Tool wear characteristics in machining of nickel-based superalloys. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2013, 64, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Chavez, L.Y.; Ruiz, A.; Lopez-Morelos, V.H.; Rubio-Gonzalez, C. Microstructural characterization and mechanical response of Inconel 600 welded joint. Mater. Charact. 2019, 157, 109882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.S.; Kim, H.P.; Cho, H.D.; Lee, H.H. Microscopic examination of an Alloy 600/182 weld. Mater. Charact. 2009, 60, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, D.; Swaroop, S. Laser shock peening enhanced corrosion properties in a nickel based Inconel 600 superalloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 694, 1309–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbewande, A.T.; Chukwukaeme, C.; Ojo, A.O. Joining of superalloy Inconel 600 by diffusion induced isothermal solidification of a liquated insert metal. Mater. Charact. 2008, 59, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Pinkerton, A.J.; Li, L. Fibre laser welding of dissimilar alloys of Ti–6Al–4V and Inconel 718 for aerospace applications. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2011, 52, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzarelli, M.; Battista, F. Oxygen-methane rocket thrust chambers: Review of heat transfer experimental studies. Acta Astronaut. 2023, 209, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immich, H.; Alting, J.; Kretschmer, J.; Preclik, D. Technology developments for thrust chambers of future launch vehicle liquid rocket engines. Acta Astronaut. 2003, 53, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degroh, H.C.I.; Ellis, D.L.; Loewenthal, W.S. Comparison of GRCop-84 to other Cu alloys with high thermal conductivities. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2008, 17, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.Q.; Jin, P.; Chen, Z.W.; Lv, J.; Cai, G. Thermal-structural analysis for reusable thrust chamber using temperature-dependent CuZr alloy model adapted to cryogenic to elevated temperature. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 145, 108782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Liu, F.J.; Zhang, X.H.; Xie, H.; Yao, C. The rapid electroforming technology of outer wall for liquid rocket engine thrust chamber. Missiles Space Veh. 2022, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Qian, J.; Hu, X.; Li, T.; Li, H. Microstructure and properties of electroformed nickel under different waveform conditions. Rare Met. 2023, 42, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velu, M.; Bhat, S. Metallurgical and mechanical examinations of steel–copper joints arc welded using bronze and nickel-base superalloy filler materials. Mater. Des. 2013, 47, 793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Abbasi, M.; Poursina, D.; Gheysarian, A.; Bagheri, B. Microstructures and mechanical properties of friction stir welded dissimilar steel-copper joints. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2017, 31, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiao, K.X.; Zhang, J.L.; Liu, J. Microstructure and mechanical properties investigations of copper-steel composite fabricated by explosive welding. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 731, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shotri, R.; Faes, K.; De, A. Magnetic pulse welding of copper to steel tubes—Experimental investigation and process modelling. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 58, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B. Recent advances in brazing fillers for joining of dissimilar materials. Metals 2021, 11, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardalani, A.; Naffakh-Moosavy, H. Investigating the microstructure and mechanical properties in furnace brazing Ti–6Al–4V to 17-4 PH stainless steel dissimilar joint with BNi-2 filler metal. J. Adv. Join. Process. 2024, 9, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.-Y.; Li, X.-Q.; Wan, B.; Zhu, D.-Z.; Qu, S.-G.; Yang, C. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of TiAl/GH536 joints vacuum brazed with Ti–Zr–Cu–Ni filler metal. Intermetallics 2022, 142, 107468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Pan, Z.; Cuiuri, D.; Li, H. Wire-feed additive manufacturing of metal components: Technologies, developments and future interests. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 81, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pixner, F.; Warchomicka, F.; Peter, P.; Steuwer, A.; Colliander, M.H.; Pederson, R.; Enzinger, N. Wire-Based Additive Manufacturing of Ti-6Al-4V Using Electron Beam Technique. Materials 2020, 13, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanjara, P.; Watanabe, K.; de Formanoir, C.; Yang, Q.; Bescond, C.; Godet, S.; Brochu, M.; Nezaki, K.; Gholipour, J.; Patnaik, P. Titanium Alloy Repair with Wire-Feed Electron Beam Additive Manufacturing Technology. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 3979471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Luan, P.; Hu, X.; Xu, C. Processing, microstructure, and mechanical behavior of AZ31 magnesium alloy fabricated by electron beam additive manufacturing. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 938, 168567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhan, B.; He, J.; Wang, K. The double-wire feed and plasma arc additive manufacturing process for deposition in Cr-Ni stainless steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 259, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junwen, J.; Zavdoveev, A.; Vedel, D.; Baudin, T.; Motrunich, S.; Klochkov, I.; Friederichs, S.; Strelenko, N.; Skoryk, M. CMT-based wire arc additive manufacturing of Inconel 625 alloy. Emerg. Mater. Res. 2023, 12, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolubaev, E.A.; Rubtsov, V.E.; Chumaevsky, A.V.; Astafurova, E.G. Micro-, meso- and macrostructural design of bulk metallic and polymetallic materials by wire-feed electron-beam additive manufacturing. Phys. Mesomech. 2022, 25, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushnarev, Y.V.; Semenchuk, V.M.; Chumaevskii, A.V.; Osipovich, K.S.; Rubtsov, V.E.; Kolubaev, E.A. Production of experimental samples of nickel-based alloy and copper nozzles by electron beam additive manufacturing. Russ. Phys. J. 2024, 67, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xiong, H.; Yu, H.; Qin, R.; Liu, W.; Yuan, H. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of wire-feed electron beam additive manufactured Ti-5Al-2Sn-2Zr-4Mo-4Cr alloy with different subtransus heat treatments. Mater. Des. 2020, 195, 109063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Yao, Z.; Tao, X.; Huang, C.; Zhang, S. Alleviating plastic anisotropy of boron modified titanium alloy by constructing layered structure via electron beam directed energy deposition. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 50, 102561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osipovich, K.; Vorontsov, A.; Chumaevskii, A.; Moskvichev, E.; Zakharevich, I.; Dobrovolsky, A.; Sudarikov, A.; Zykova, A.; Rubtsov, V.; Kolubaev, E. Features of microstructure and texture formation of large-sized blocks of C11000 copper produced by electron beam wire-feed additive technology. Materials 2022, 15, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osipovich, K.S.; Astafurova, E.G.; Chumaevskii, A.V.; Kalashnikov, K.N.; Astafurov, S.V.; Maier, G.G.; Melnikov, E.V.; Moskvina, V.A.; Panchenko, M.Y.; Tarasov, S.Y.; et al. Gradient transition zone structure in “steel–copper” sample produced by double wire-feed electron beam additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 9258–9272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Chen, G.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Feng, J. Microstructure evolution of copper/steel gradient deposition prepared using electron beam freeform fabrication. Mater. Lett. 2018, 213, 374–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norkett, J.E.; Fisher, C.R. Temperature-dependent material property database of cast 70/30 Cu–Ni material. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 2025, 14, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, G. Mechanical properties of undercooled Cu70Ni30 alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 2000, 35, 5581–5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wu, H.-B.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Gao, F.; Zhou, X.-D. Effect of thickness reduction on microstructure and properties of rolled C71500 cupronickel alloy tube. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 3273–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, Z.; Qing, W.; Yingmin, W.; Lishi, W.; Chuang, D. Effect of heat treatment on the highly corrosion-resistant Cu70Ni27.7Fe2.3 alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 505, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Gan, R.; Xiao, H.; Shen, Y. Cavitation erosion characterization of Cu–Ni alloy laser cladding layer under the action of high-pressure water jet. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1020, 179325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wu, H.-B.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Zhou, X.-D. Dynamic recovery and recrystallization behaviors of C71500 copper–nickel alloy under hot deformation. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 7678–7692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, M. Corrosion behavior of high-strength C71500 copper–nickel alloy in simulated seawater with high concentration of sulfide. Materials 2022, 15, 8513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnati, S.; Liou, F.F.; Newkirk, J.W. Characterization of copper–nickel alloys fabricated using laser metal deposition and blended powder feedstocks. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 103, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Gao, S.; Wang, L.; Ding, J.; Lu, Y.; Wen, Y.; Qu, X.; Zhang, B.; Song, X. Full-composition-gradient in-situ alloying of Cu–Ni through laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 85, 104166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B. Material properties of gradient copper–nickel alloy fabricated by wire arc additive manufacturing based on bypass-current PAW. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 83, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraz, V.R.; Gerasimov, S.S.; Gruzdeva, I.A.; Shveikin, V.P.; Chemesova, A.V.; Ovchinnikova, A.O.; Veretennikova, I.A. The additive technology to obtain a three-dimensional model of the 81Cu–19Ni alloy. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 966, 012119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleta, M.; Kulasa, J.; Kowalski, A.; Kwaśniewski, P.; Boczkal, S.; Nowak, M. Microstructure, mechanical and corrosion properties of Copper–Nickel 90/10 alloy produced by CMT-WAAM method. Materials 2023, 17, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, N.; Snyder, K.; Smith, I.; Duong, A.; Carpenter, E.; Barua, R. The first layer: Single-track insights into direct energy deposition processed Cu–Ni thermoelectric alloys. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.T.; Panwisawas, C.; Ghoussoub, J.N.; Gong, Y.; Clark, J.; Németh, A.; McCartney, D.G.; Reed, R.C. Alloys-by-design: Application to new superalloys for additive manufacturing. Acta Mater. 2021, 202, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsoy, A.; Gaudez, S.; Hearn, W.A.; Baganis, A.; Hegedüs, Z.; Chen, Y.; Rack, A.; Logé, R.E.; Van Petegem, S. Phase-separation-driven cracking in additive manufacturing of Ni-Cu alloy systems. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 110, 104950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.; Guimarães, B.; Cerqueira, M.; Silva, F.; Carvalho, O. Multi-Material Inconel 718 Parts with Highly Conductive Copper Cooling Channels for Aerospace Applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2023, 25, 2201349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belan, J. GCP and TCP phases presented in nickel-base superalloys. Mater. Today Proc. 2016, 3, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Cu | Ni | Cr | Mo | Nb | Fe | Mn | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C11000 | 99.9 | up to 0.002 | - | - | - | up to 0.005 | - | - |

| Inconel 625 | - | 58.0 | 20.0–23.0 | 8.0–10.0 | 3.2–4.2 | 5.0 | up to 0.05 | up to 0.1 |

| Specimens | Material | Beam Current, mA | Scanning Speed, mm/min | Wire Feed Speed, mm/min | Estimated Layer Height, mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A | Inconel 625 | 86.0 → 60.0 | 350.0 | 1392.6 | 1.0 |

| C11000 | 90.0 → 115.0 | 400.0 | 1591.5 | 1.0 | |

| Type B | Inconel 625 | 85.6 → 39.0 | 250.0 | 1293.1 | 1.3 |

| C11000 | 55.0 | 350.0 | 1392.6 | 1.0 | |

| Type C | Inconel 625 | 78.0 → 70.0 | 350.0 | 1392.6 | 1.0 |

| C11000 | 65.0 | 250.0 | 1293.1 | 1.3 |

| Specimens | Impact Toughness, kJ/sm2 | Cycles to Failure, ×1000 | YS, MPa | UTS, MPa | Elongation, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A | 44.5 | 135 * | 415 | 755 | 69 |

| Type B | 32.0 | 1000 | 350 * | 730 * | 72 |

| Type C | 41.0 | 1000 | 325 * | 665 * | 73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Osipovich, K.; Semenchuk, V.; Chumaevskii, A.; M. Korsunsky, A.; Kushnarev, Y.; Moskvichev, E.; Amirov, A.; Gurianov, D.; Tarasov, S.; Kolubaev, E. On the Heterogeneity of Deformation and Fracture in Bimetallic Specimens of the C11000-Inconel 625 System. Materials 2025, 18, 5450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235450

Osipovich K, Semenchuk V, Chumaevskii A, M. Korsunsky A, Kushnarev Y, Moskvichev E, Amirov A, Gurianov D, Tarasov S, Kolubaev E. On the Heterogeneity of Deformation and Fracture in Bimetallic Specimens of the C11000-Inconel 625 System. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235450

Chicago/Turabian StyleOsipovich, Kseniya, Vyacheslav Semenchuk, Andrey Chumaevskii, Alexander M. Korsunsky, Yuri Kushnarev, Evgeny Moskvichev, Alihan Amirov, Denis Gurianov, Sergei Tarasov, and Evgeny Kolubaev. 2025. "On the Heterogeneity of Deformation and Fracture in Bimetallic Specimens of the C11000-Inconel 625 System" Materials 18, no. 23: 5450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235450

APA StyleOsipovich, K., Semenchuk, V., Chumaevskii, A., M. Korsunsky, A., Kushnarev, Y., Moskvichev, E., Amirov, A., Gurianov, D., Tarasov, S., & Kolubaev, E. (2025). On the Heterogeneity of Deformation and Fracture in Bimetallic Specimens of the C11000-Inconel 625 System. Materials, 18(23), 5450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235450