Impact of Varied Recycled Aggregate Inclusions on Mechanical Properties and Damage Evolution Based on Multiphase Inclusion Theory

Highlights

- Hard inclusions disperse stress, enhancing the overall stiffness.

- Soft inclusions consistently exhibit stress concentration.

- Similar inclusions as the base materials provide stress compatibility

- Multiphase Inclusion Theory demonstrates predictive capability for stress concentration.

- It also supports the advanced design and optimization of composite materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

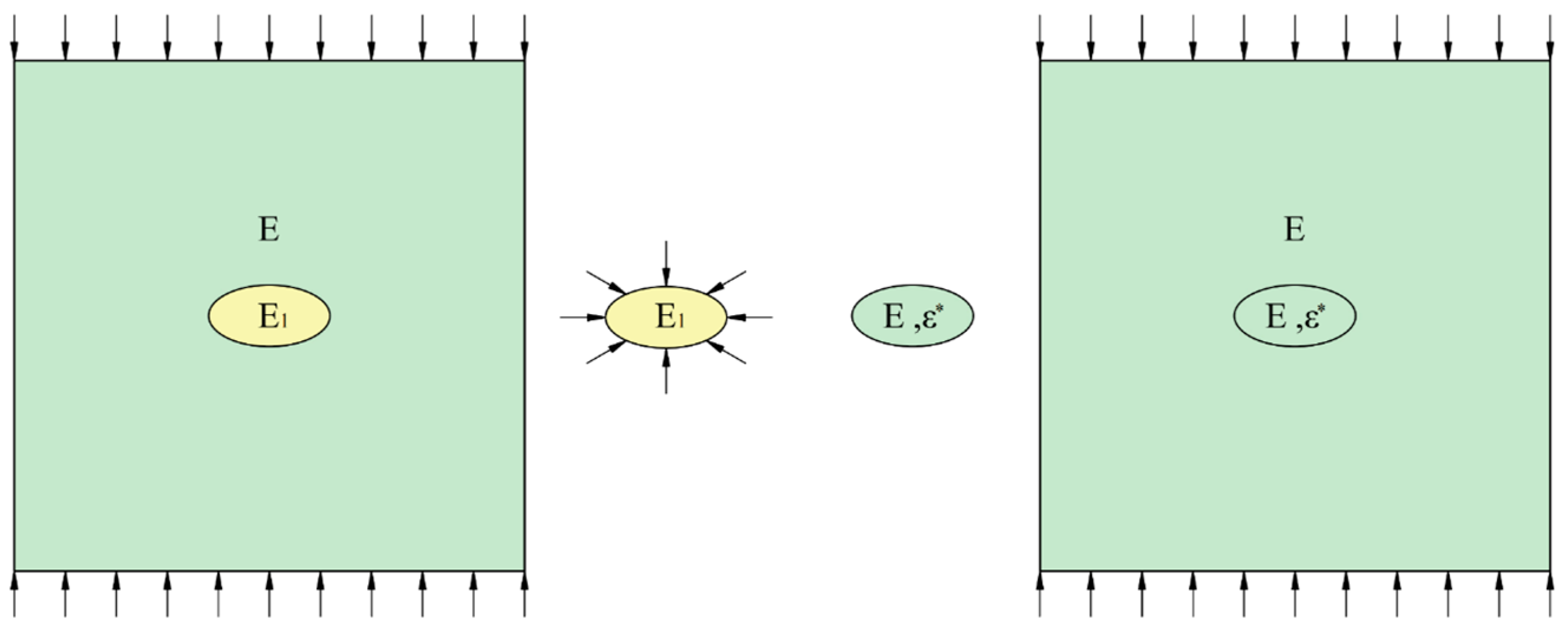

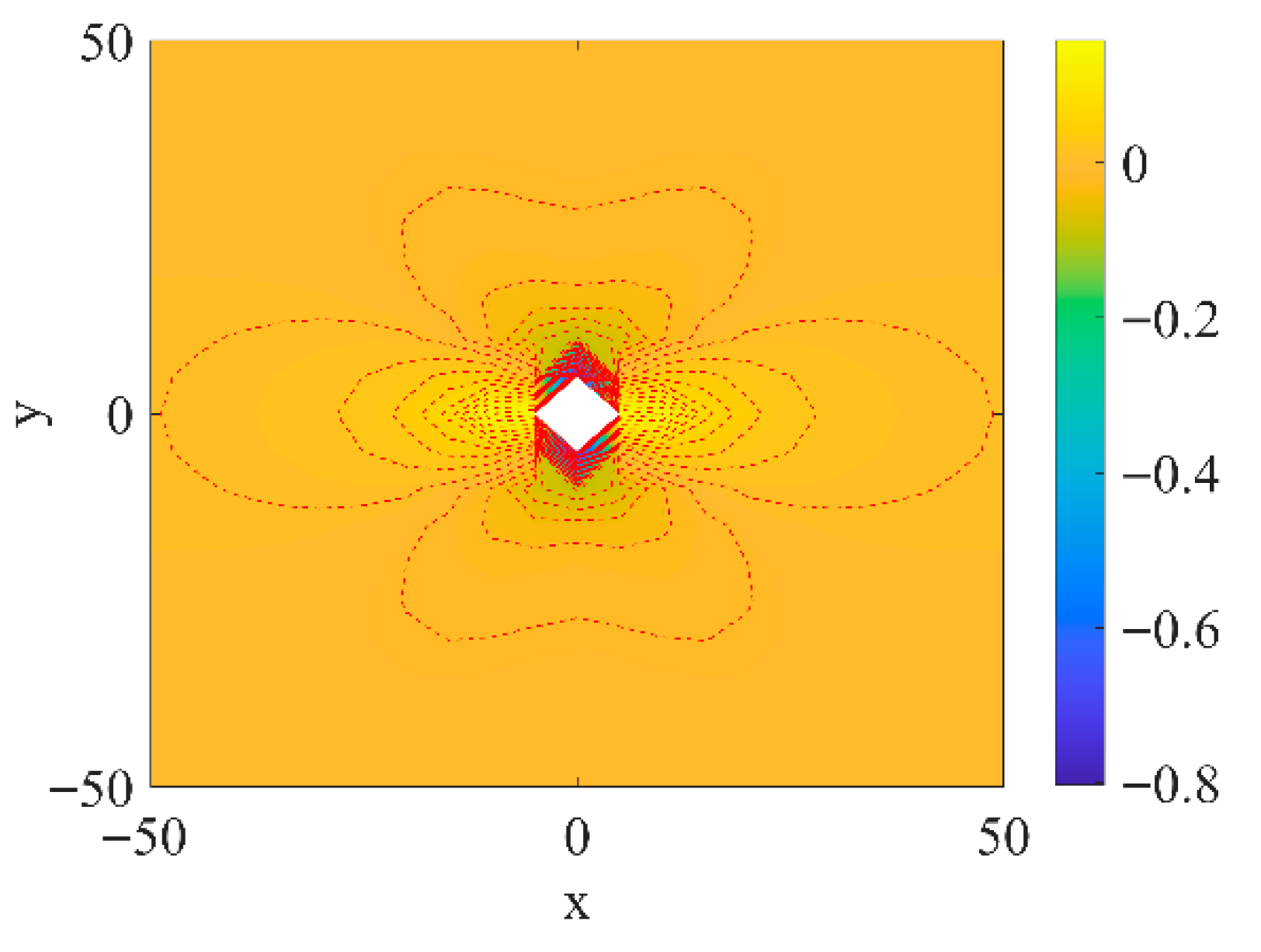

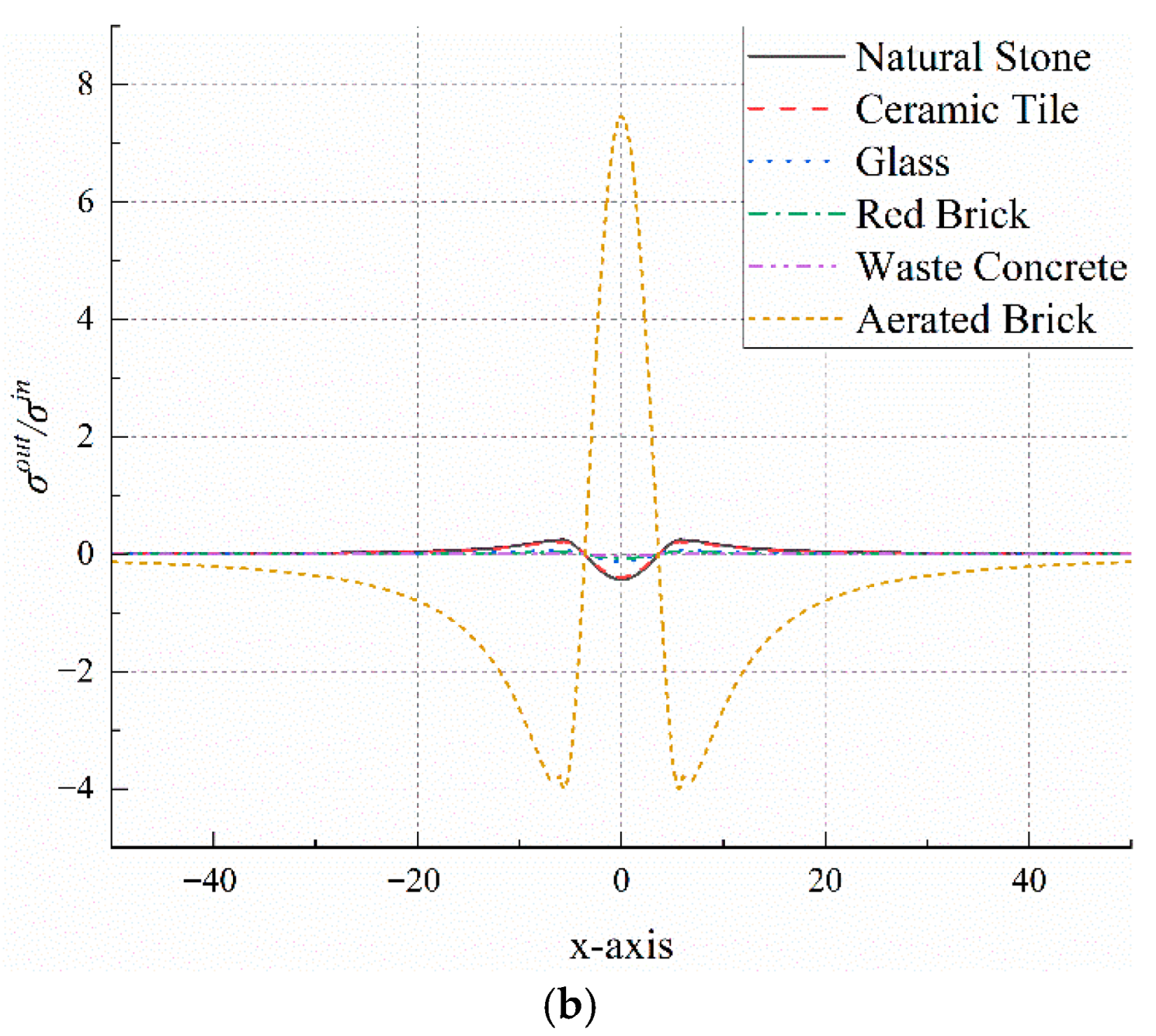

2. Stress Distribution Analysis Based on MIT

2.1. Overall Mechanical Properties Analysis Based on MIT

2.2. Determining the Internal and External Stress Fields of the Inclusion

3. Experimental Study of Model Recycled Concrete

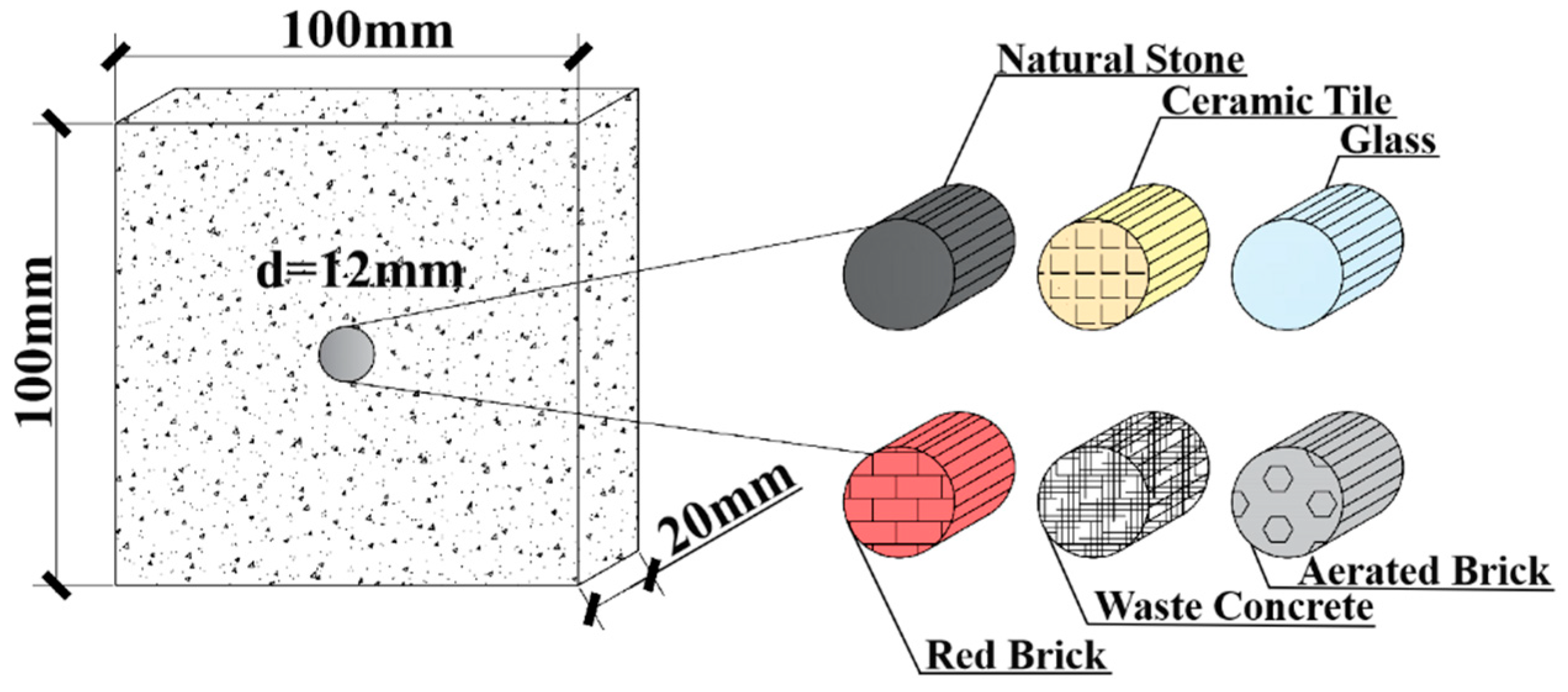

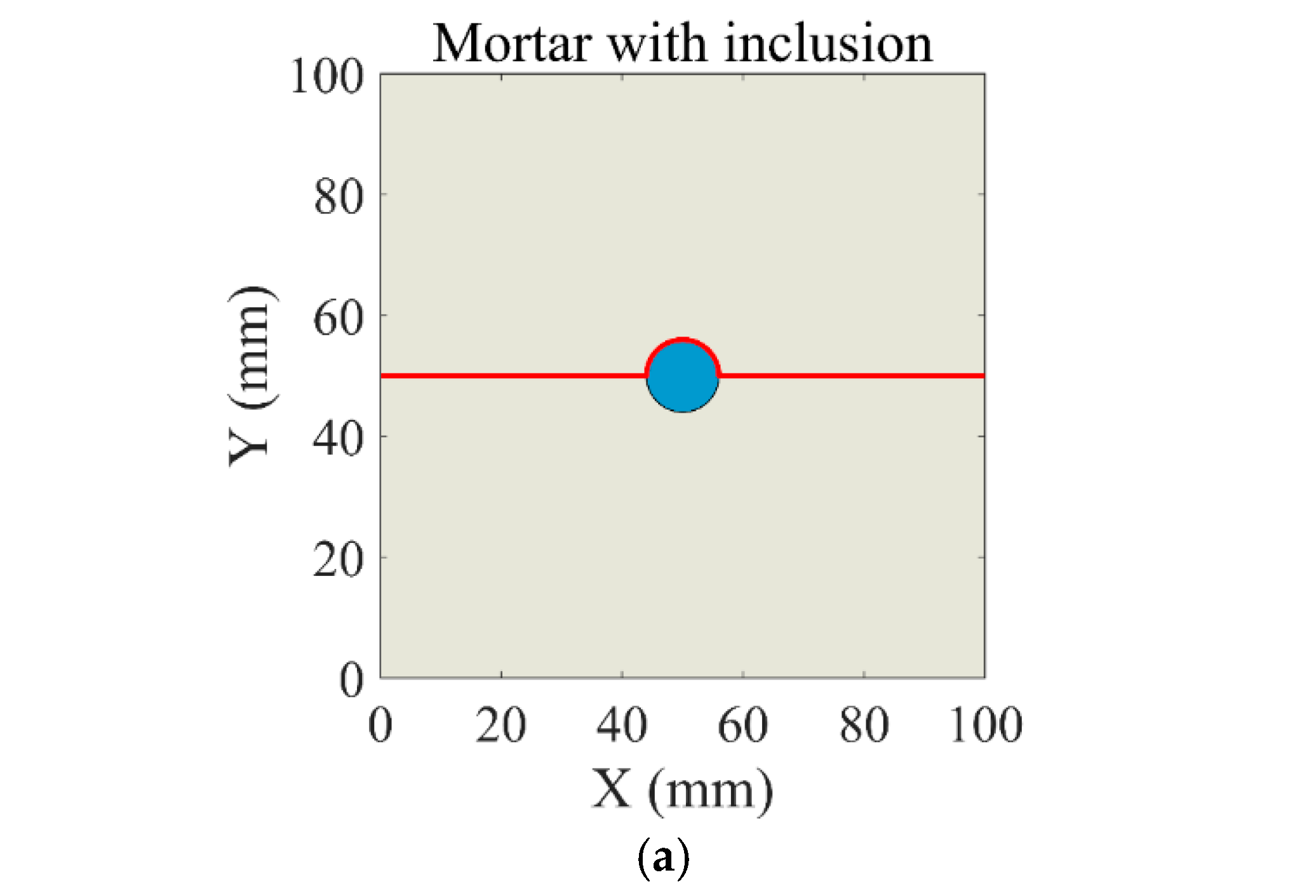

3.1. Concept of Model Recycled Concrete

3.2. Specimen Preparation and Model Fabrication

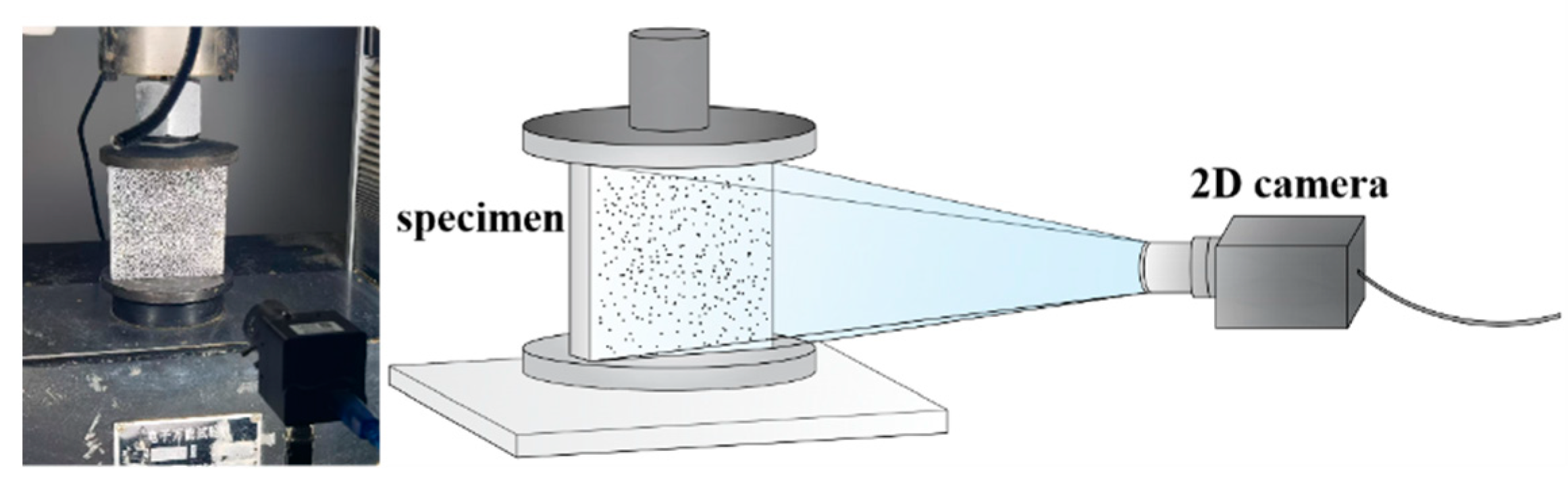

3.3. Testing Method

4. Results and Discussion

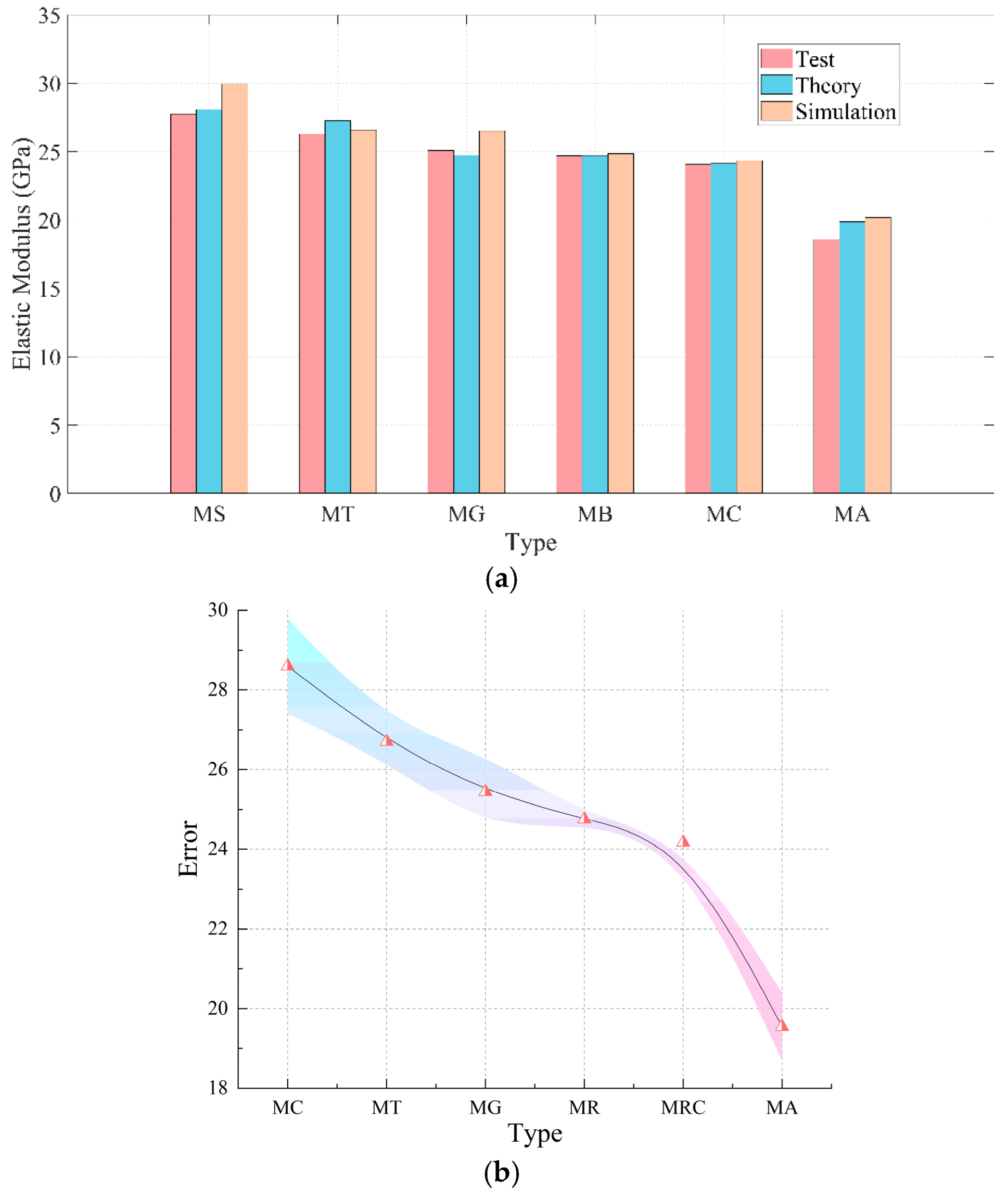

4.1. Mechanical Properties

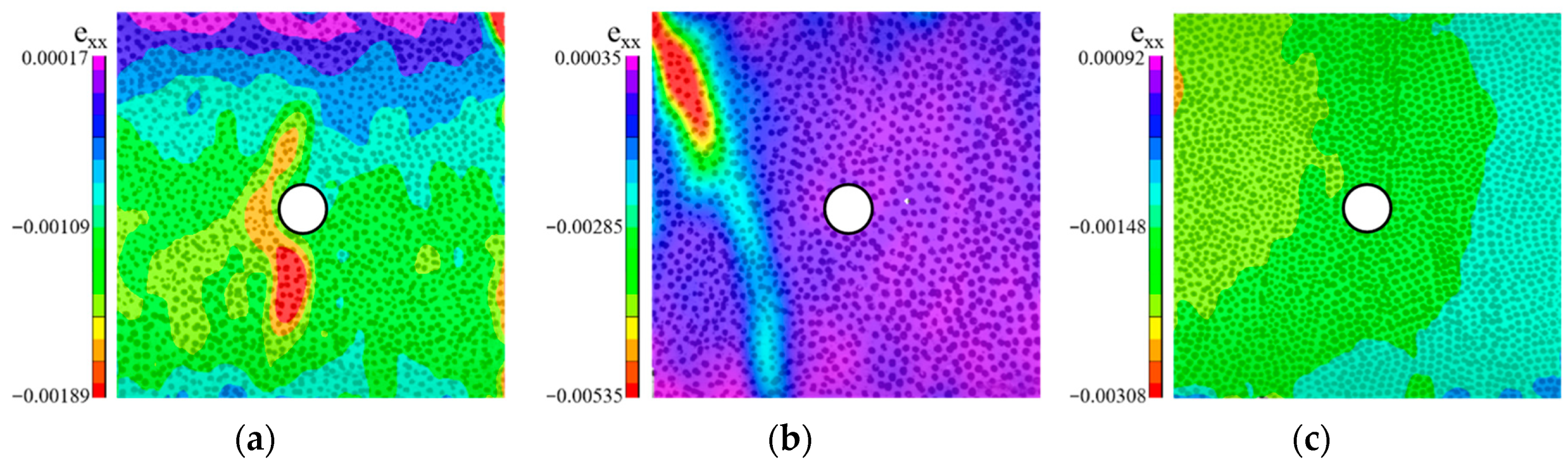

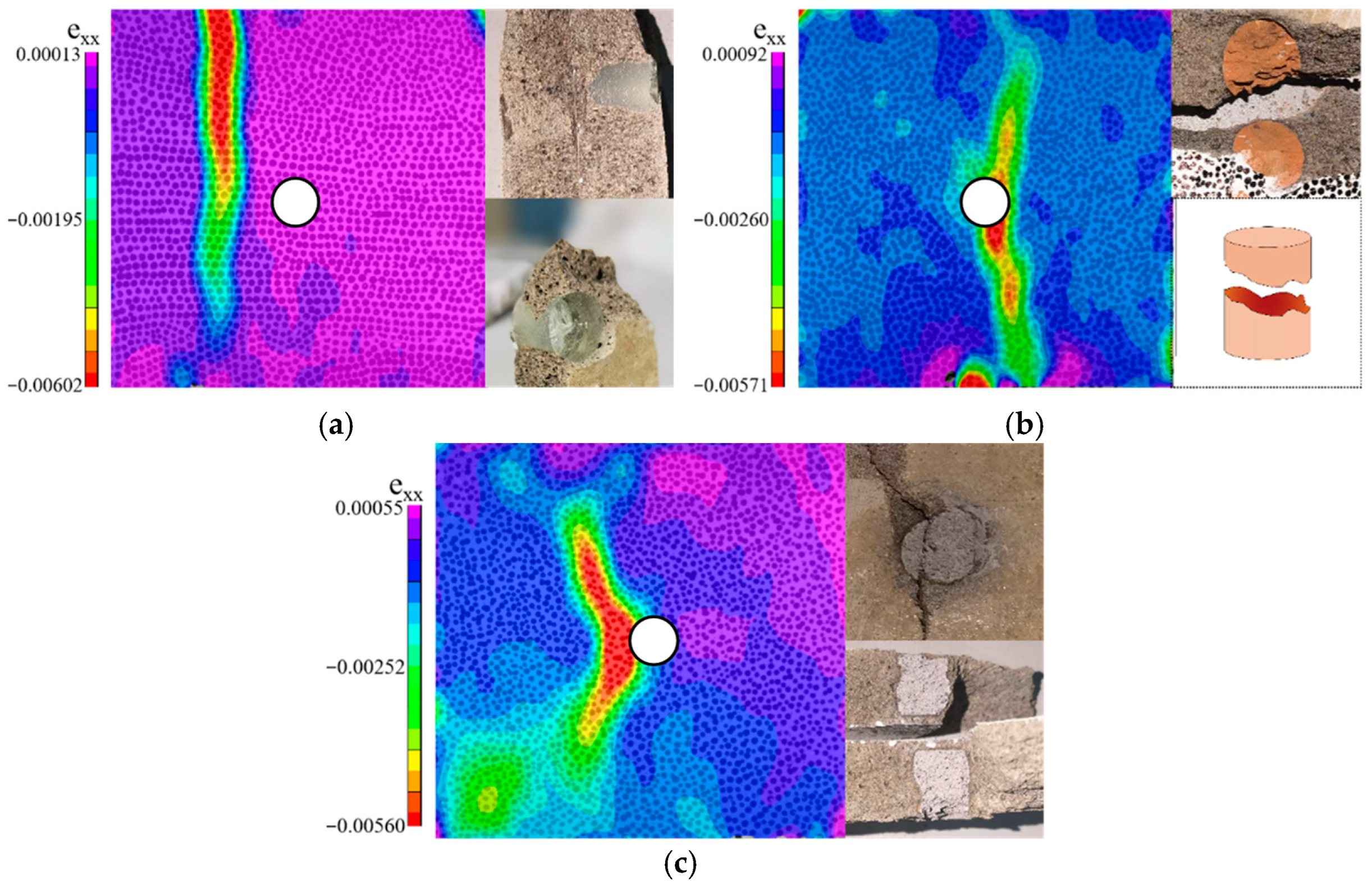

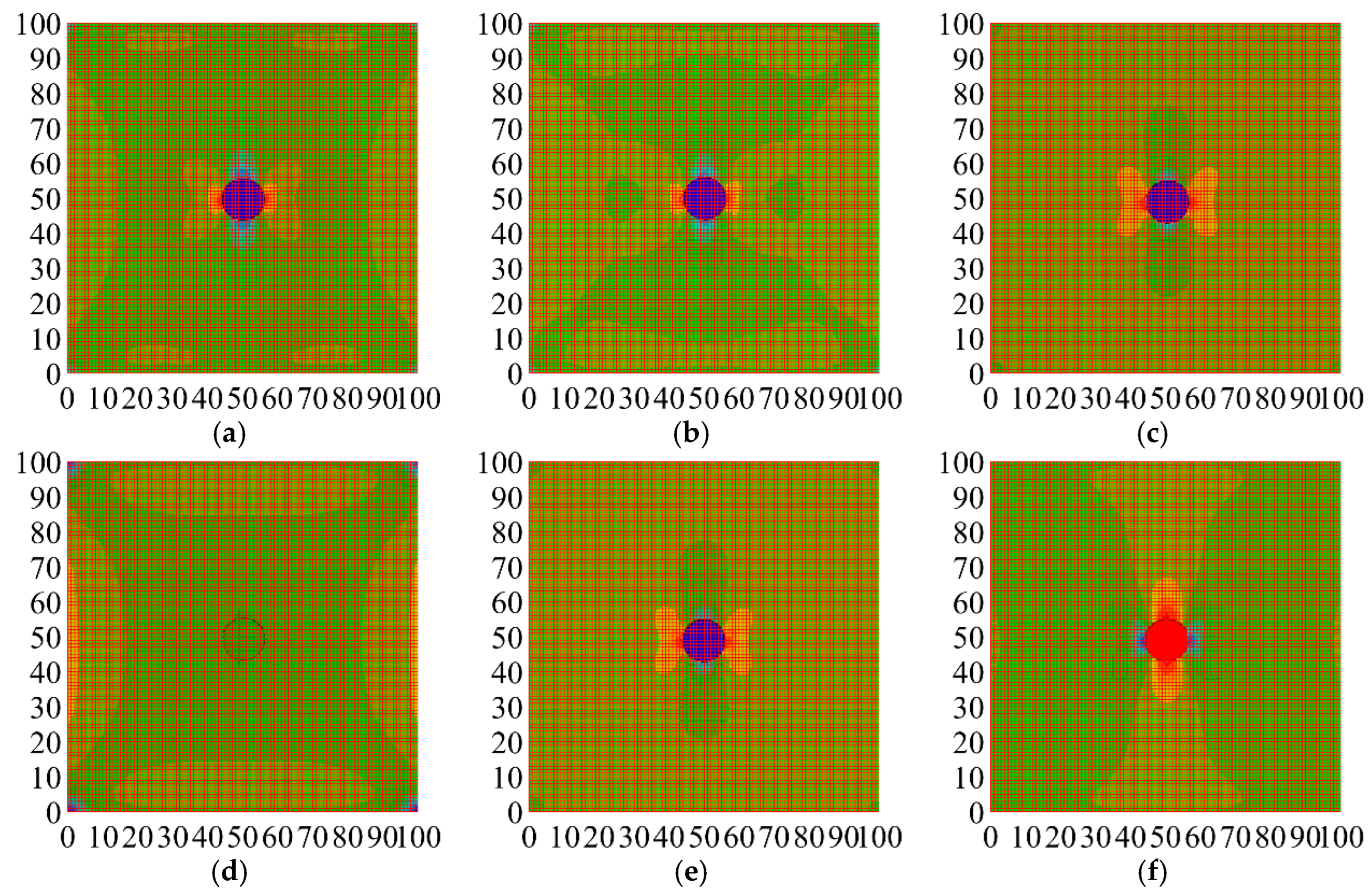

4.2. Damage Evolution

4.2.1. MS

4.2.2. MT

4.2.3. MG

4.2.4. MC

4.2.5. MB

4.2.6. MA

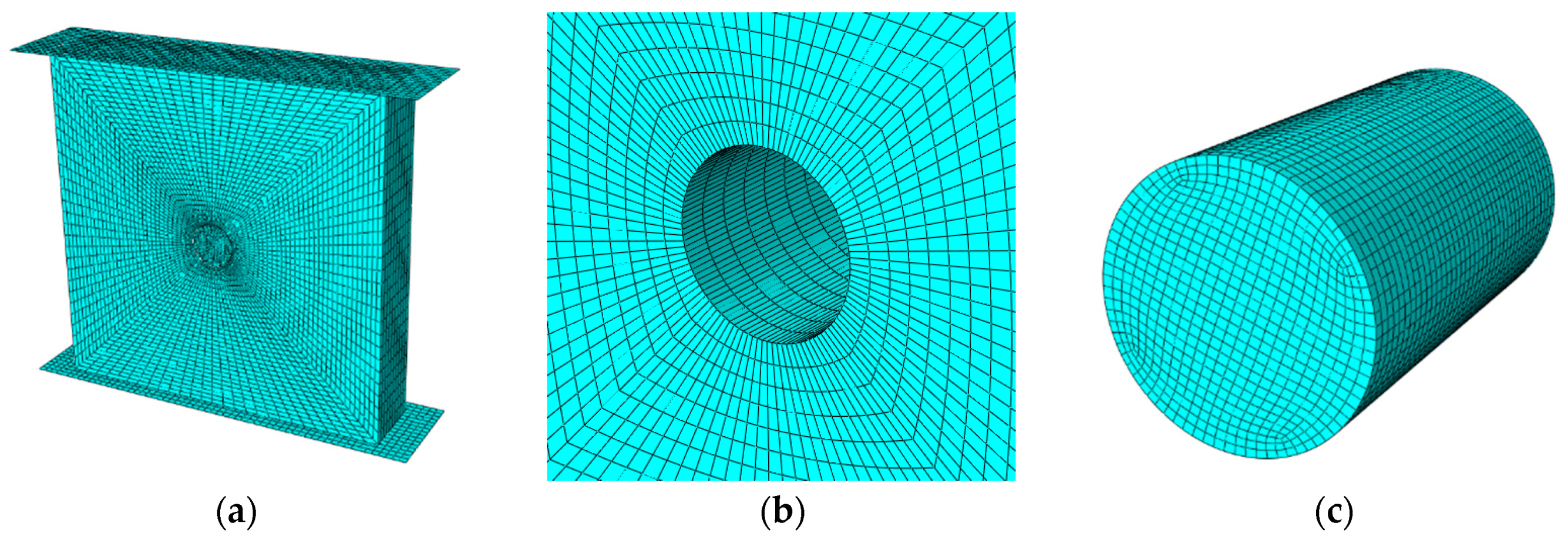

4.3. FEM Establishment of Model Recycled Concrete

4.4. Comparative Analysis of Elastic Stage

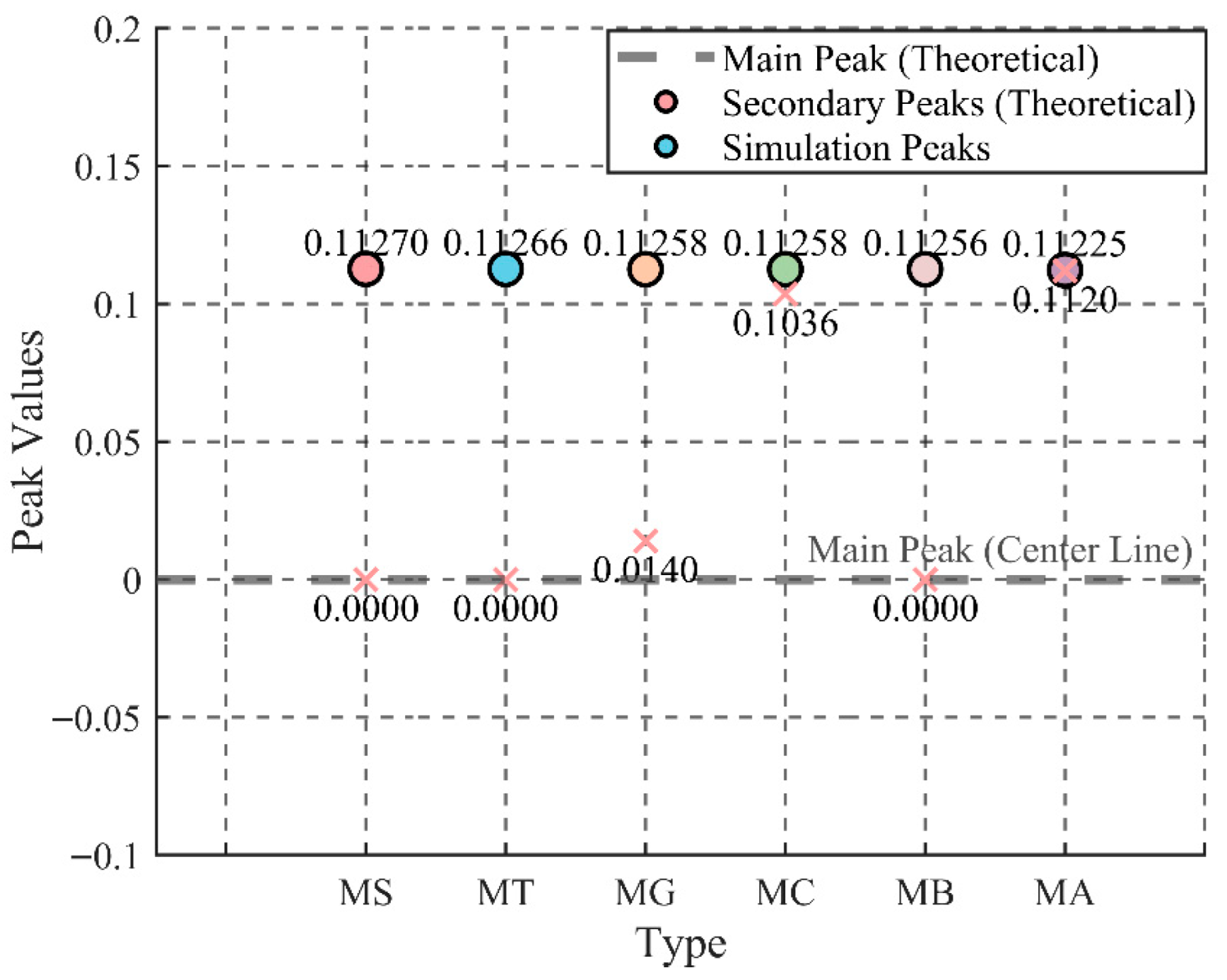

4.5. Comparative Analysis of Stress Concentration

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Detailed Formulations of Multiphase Inclusion Theory

Appendix A.1. Overall Mechanical Properties Analysis Based on MIT

Appendix A.1.1. Basic Eshelby Theory Formulations

Appendix A.1.2. Homogenization and Effective Properties

Appendix A.1.3. Dilute Approximation and Mori–Tanaka Method

Appendix A.2. Determining the Internal and External Stress Fields of the Inclusion

Appendix A.2.1. Internal Stress Field

Appendix A.2.2. Solution for the Eigenstress and External Field

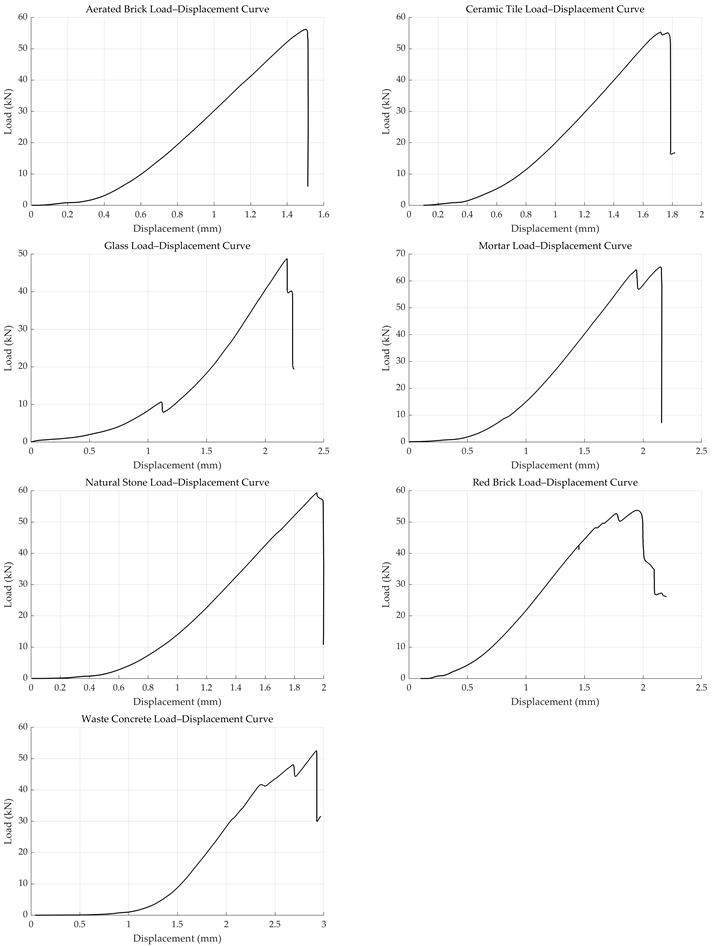

Appendix B. Representative Load–Displacement Curves of Constituent Materials

References

- Xiao, J.; Li, L.; Shen, L.; Poon, C.S. Compressive Behaviour of Recycled Aggregate Concrete under Impact Loading. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 71, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, W.; Corr, D.J.; Shah, S.P. Effects of Interfacial Transition Zones on the Stress–Strain Behavior of Modeled Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 52, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xiao, J.; Poon, C.S.; Li, L. Investigation on Modeled Recycled Concrete Prepared with Recycled Concrete Aggregate and Recycled Brick Aggregate. Jianzhu Jiegou Xuebao J. Build. Struct. 2020, 41, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, W.; Liu, Q. Meso-Level Numerical Simulation on Mechanical Properties of Modeled Recycled Concrete under Uniaxial Compression. Tongji Daxue Xuebao J. Tongji Univ. 2011, 39, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.W.Y.; Soomro, M.; Evangelista, A.C.J. A Review of Recycled Aggregate in Concrete Applications (2000–2017). Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 172, 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.B.; Lee, B.C.; Kim, J.H. Studies on Mechanical Properties of Concrete Containing Waste Glass Aggregate. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 2181–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabsh, S.W.; Abdelfatah, A.S. Influence of Recycled Concrete Aggregates on Strength Properties of Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 1163–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jin, C.; Li, X. Impact of Interfacial Transition Zone on Concrete Mechanical Properties: A Comparative Analysis of Multiphase Inclusion Theory and Numerical Simulations. Coatings 2024, 14, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbachiya, M.C.; Leelawat, T.; Dhir, R.K. Use of Recycled Concrete Aggregate in High-Strength Concrete. Mater. Struct. 2000, 33, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez del Bosque, I.F.; Zhu, W.; Howind, T.; Matías, A.; Sánchez de Rojas, M.I.; Medina, C. Properties of Interfacial Transition Zones (ITZs) in Concrete Containing Recycled Mixed Aggregate. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 81, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, A.; Khan, F.A.; Khan, S.W.; Haq, I.U.; Li, D.; Khan, D. Experimental Study on the Mechanical Behavior of Concrete Incorporating Fly Ash and Marble Powder Waste. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19147. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-70303-y (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Poon, C.S.; Kou, S.C.; Lam, L. Influence of Recycled Aggregate on Slump and Bleeding of Fresh Concrete. Mater. Struct. 2007, 40, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, S.-C.; Poon, C.-S.; Etxeberria, M. Influence of Recycled Aggregates on Long Term Mechanical Properties and Pore Size Distribution of Concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Li, W. Uniaxial Compressive Behaviors of Fly Ash/Slag-Based Geopolymeric Concrete with Recycled Aggregates. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 104, 103375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Heede, P.; De Belie, N. Environmental Impact and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Traditional and ‘Green’ Concretes: Literature Review and Theoretical Calculations. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letelier, V.; Tarela, E.; Moriconi, G. Mechanical Properties of Concretes with Recycled Aggregates and Waste Brick Powder as Cement Replacement. Procedia Eng. 2017, 171, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Thaickavil, N.N.; Wilson, P.M. Strength and Durability of Concrete Containing Recycled Concrete Aggregates. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 19, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshelby, J.D. The Determination of the Elastic Field of an Ellipsoidal Inclusion, and Related Problems. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1957, 241, 376–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.W.; Sun, L.Z. A Novel Formulation for the Exterior-Point Eshelby’s Tensor of an Ellipsoidal Inclusion. J. Appl. Mech. 1999, 66, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Fan, H.; Li, S. Interphase Model for Effective Moduli of Nanoparticle-Reinforced Composites. J. Eng. Mech. 2015, 141, 04015052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, W.; Sun, Z.; Shah, S.P. Crack Propagation in Recycled Aggregate Concrete under Uniaxial Compressive Loading. ACI Mater. J. 2012, 109, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xiao, J.; Zhi, X.; Wang, Z. Damage Evolution Study of Modeled Recycled Concrete Based on Orientation of Recycled Aggregate. Tongji Daxue Xuebao J. Tongji Univ. 2020, 48, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blikharskyy, Y.; Kopiika, N.; Khmil, R.; Selejdak, J.; Blikharskyy, Z. Review of Development and Application of Digital Image Correlation Method for Study of Stress–Strain State of RC Structures. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.; Sommacal, S.; Das, R.; Stachurski, Z.; Compston, P. Digital Image and Volume Correlation for Deformation and Damage Characterisation of Fibre-Reinforced Composites: A Review. Compos. Struct. 2023, 315, 116994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeliukstis, R.; Chen, X. Review of Digital Image Correlation Application to Large-Scale Composite Structure Testing. Compos. Struct. 2021, 271, 114143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, C. Mechanical Properties of Recycled Aggregate Concrete under Uniaxial Loading. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Hu, S.; Hua, K. Mesoscale Finite Element Modeling of Recycled Aggregate Concrete under Axial Tension. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 266, 121002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchione, F. Analytical Investigation on the Stress Distribution in Structural Elements Reinforced with Laminates Subjected to Axial Loads. IJE 2022, 35, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Average (GPa) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Average (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS-1 | 27.65 | 28.13 ± 0.46 | 37.17 | 36.03 ± 1.39 | 0.2392 | 0.2396 ± 0.0019 |

| MS-2 | 28.55 | 36.54 | 0.2417 | |||

| MS-3 | 28.25 | 34.39 | 0.2380 | |||

| MT-1 | 26.78 | 27.28 ± 0.47 | 27.28 | 28.52 ± 1.25 | 0.2375 | 0.2298 ± 0.0091 |

| MT-2 | 27.68 | 29.78 | 0.2322 | |||

| MT-3 | 27.38 | 28.76 | 0.2196 | |||

| MG-1 | 23.72 | 24.22 ± 0.47 | 24.40 | 24.14 ± 1.08 | 0.2285 | 0.2255 ± 0.0052 |

| MG-2 | 24.62 | 22.95 | 0.2195 | |||

| MG-3 | 24.32 | 25.08 | 0.2285 | |||

| MB-1 | 23.86 | 24.36 ± 0.45 | 22.93 | 21.45 ± 1.30 | 0.2426 | 0.2391 ± 0.0080 |

| MB-2 | 24.76 | 21.10 | 0.2448 | |||

| MB-3 | 24.46 | 20.34 | 0.2299 | |||

| MC-1 | 23.54 | 24.04 ± 0.46 | 26.80 | 26.50 ± 0.52 | 0.2535 | 0.2412 ± 0.0115 |

| MC-2 | 24.44 | 26.86 | 0.2312 | |||

| MC-3 | 24.14 | 25.83 | 0.2390 | |||

| MA-1 | 18.79 | 19.29 ± 0.46 | 18.15 | 19.63 ± 1.34 | 0.2195 | 0.2249 ± 0.0075 |

| MA-2 | 19.69 | 19.90 | 0.2209 | |||

| MA-3 | 19.39 | 20.83 | 0.2342 |

| Material Type | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Stone | 75.0 | 170.1 | 0.360 |

| Ceramic Tile | 60.0 | 107.1 | 0.225 |

| Glass | 29.8 | 97.3 | 0.221 |

| Red Brick | 26.8 | 9.7 | 0.217 |

| Waste Concrete | 25.0 | 30.1 | 0.225 |

| Aerated Brick | 2.0 | 5.0 | 0.201 |

| Mortar | 24.0 | 33.32 | 0.238 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Y.; Chen, T.; Gao, X.; Jin, C.; Liu, Q. Impact of Varied Recycled Aggregate Inclusions on Mechanical Properties and Damage Evolution Based on Multiphase Inclusion Theory. Materials 2025, 18, 5430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235430

Ma Y, Chen T, Gao X, Jin C, Liu Q. Impact of Varied Recycled Aggregate Inclusions on Mechanical Properties and Damage Evolution Based on Multiphase Inclusion Theory. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235430

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Yongsheng, Tiefeng Chen, Xiaojian Gao, Congkai Jin, and Qiong Liu. 2025. "Impact of Varied Recycled Aggregate Inclusions on Mechanical Properties and Damage Evolution Based on Multiphase Inclusion Theory" Materials 18, no. 23: 5430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235430

APA StyleMa, Y., Chen, T., Gao, X., Jin, C., & Liu, Q. (2025). Impact of Varied Recycled Aggregate Inclusions on Mechanical Properties and Damage Evolution Based on Multiphase Inclusion Theory. Materials, 18(23), 5430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235430