Synthesis of Few-Layer Graphene from Lignin and Its Application for the Creation of Thermally Conductive and UV-Protective Coatings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Initial Material for Synthesis of Coatings

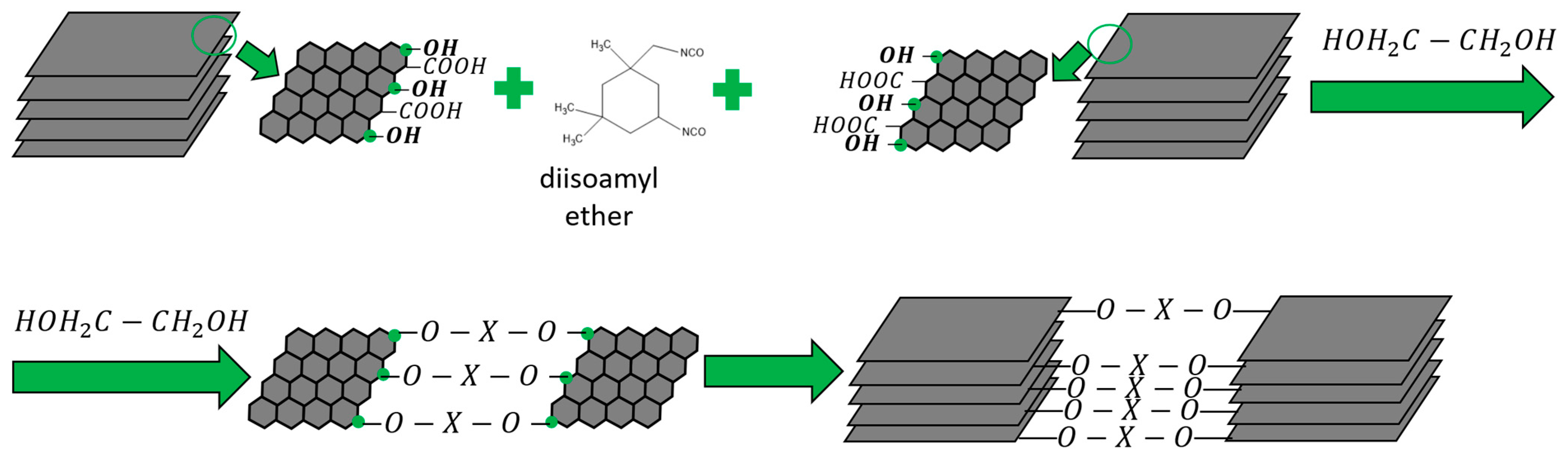

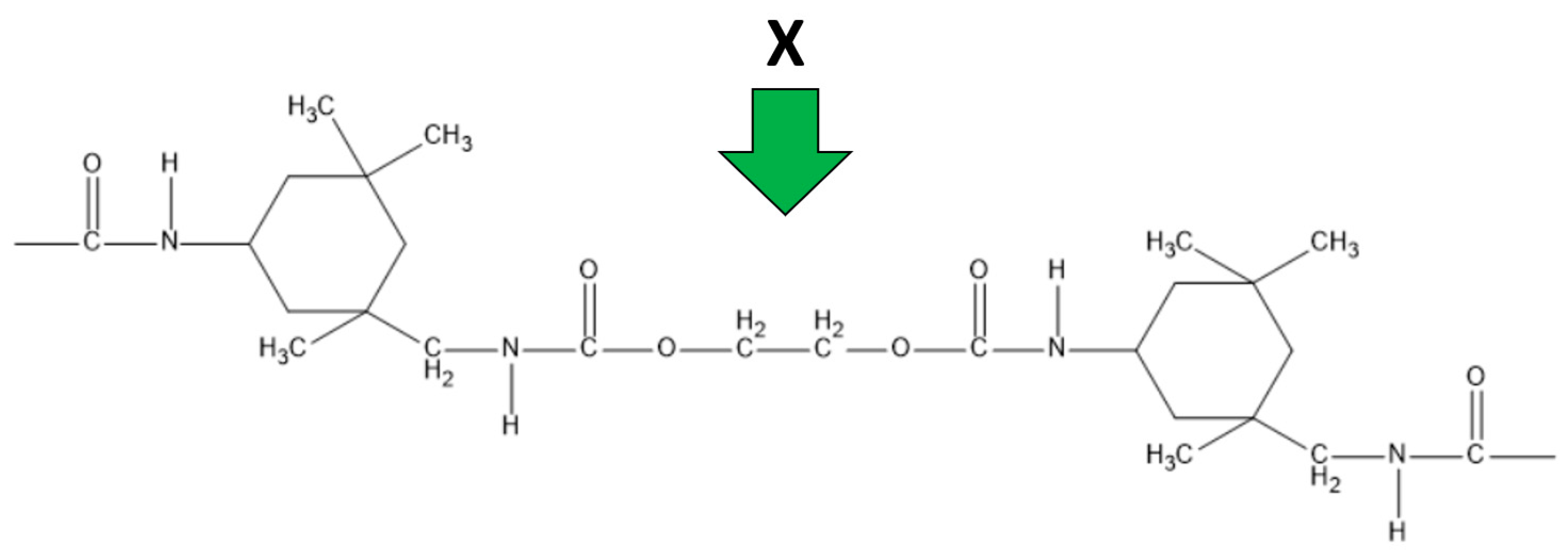

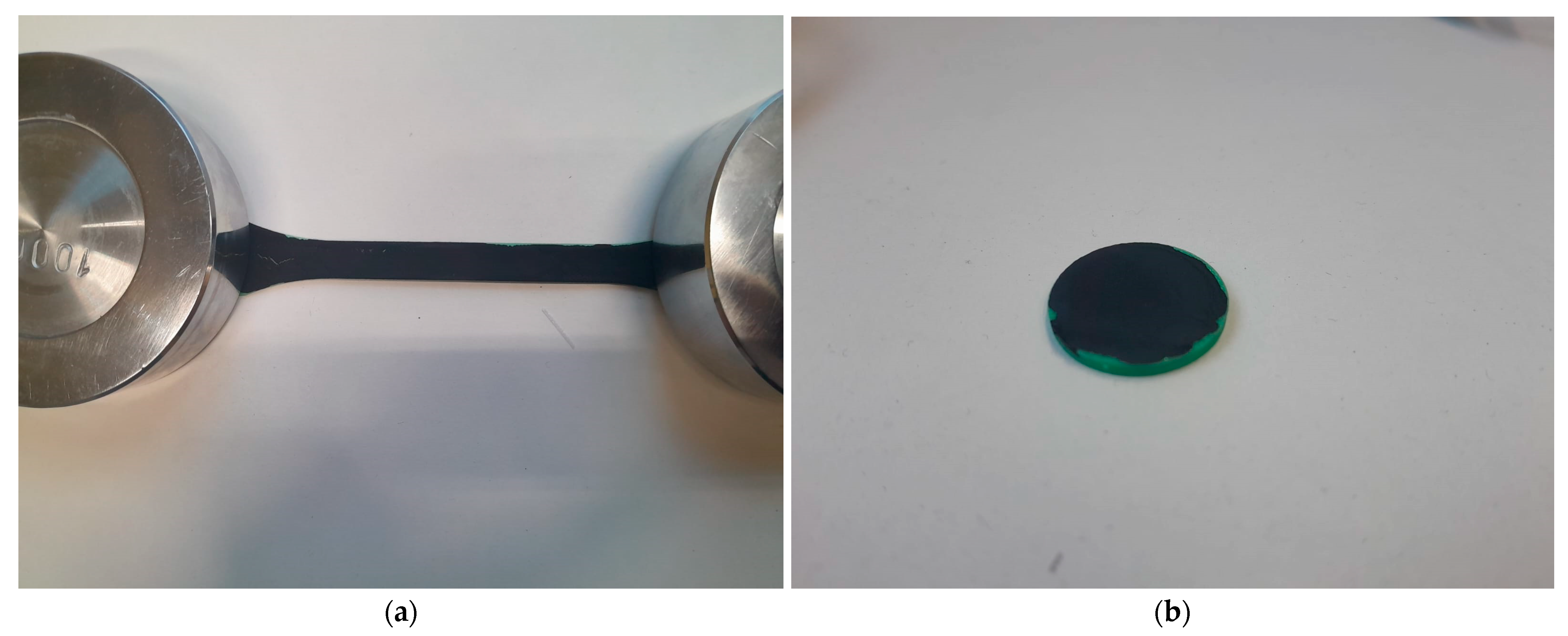

2.2. Coating Synthesis Methodology

2.3. Characterization Methods of Initial Few-Layer Graphene and Coatings Based on FLG

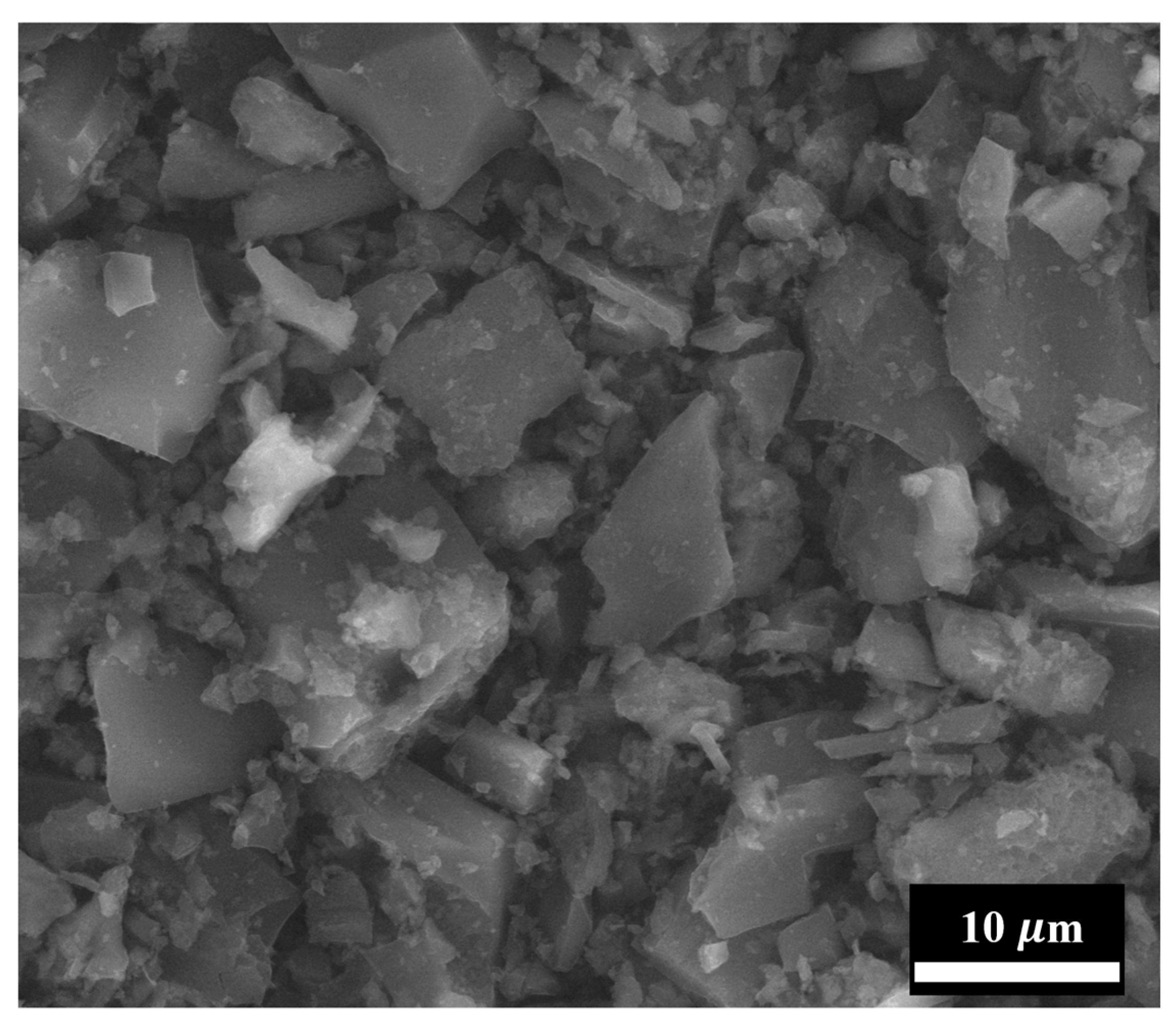

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FLG | few-layer graphene |

| GNS | graphene nanostructures |

| CVD | Chemical vapor deposition |

| SHS | self-propagating high-temperature synthesis |

References

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, M.; Jin, W.; Zhang, J.; Fan, G.; Feng, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Lee, J.S.; Luan, G.; et al. A comprehensive review of unlocking the potential of lignin-derived biomaterials: From lignin structure to biomedical application. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chio, C.; Sain, M.; Qin, W. Lignin Utilization: A Review of Lignin Depolymerization from Various Aspects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 107, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, J.; Lapierre, C.; Boerjan, W. Lignin Structure and Its Engineering. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 56, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthäuser, J.; Biziks, V.; Mai, C.; Militz, H. Lignin and Lignin-Derived Compounds for Wood Applications—A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, O.; Kim, K.H. Lignin to Materials: A Focused Review on Recent Novel Lignin Applications. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libretti, C.; Correa, L.S.; Meier, M.A.R. From waste to resource: Advancements in sustainable lignin modification. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 4358–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, D.C.; Ma, Z.; Romero, J.J. The Antimicrobial Properties of Technical Lignins and Their Derivatives—A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arrigo, P.; Rossato, L.A.; Strini, A.; Serra, S. From waste to value: Recent insights into producing vanillin from lignin. Molecules 2024, 29, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Ren, B.; Cheng, H. Conversion of lignin to nitrogenous chemicals and functional materials. Materials 2024, 17, 5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/TS 21356-1:2021; Nanotechnologies—Structural Characterization of Graphene—Part 1: Graphene from Powders and Dispersions. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Balandin, A.A.; Ghosh, S.; Calizo, I.; Teweldebrhan, D.; Miao, F.; Lau, C.N. Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 902–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urade, A.R.; Lahiri, I.; Suresh, K.S. Graphene properties, synthesis and applications: A review. Jom 2023, 75, 614–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollik, K.; Lieder, M. Review of the application of graphene-based coatings as anticorrosion layers. Coatings 2020, 10, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, N.F.; Park, J.; Oh, H. Facile tool for green synthesis of graphene sheets and their smart free-standing UV protective film. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 458, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staneva, A.D.; Dimitrov, D.K.; Gospodinova, D.N.; Vladkova, T.G. Antibiofouling activity of graphene materials and graphene-based antimicrobial coatings. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; He, P.; Yang, S.; Ding, G. Thermally Conductive Graphene-Based Films for High Heat Flux Dissipation. Carbon 2025, 233, 119908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriani, A.B.; Mohamed, A.; Mamat, M.H.; Muti, N.; Ismail, R.; Malek, M.F.; Ahmad, M.K. Synthesis, Transfer and Application of Graphene as a Transparent Conductive Film: A Review. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2020, 43, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fang, Y.; Ou, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, L.; Zhou, F.; Liu, W. Synergistic Anti-Corrosion and Anti-Wear of Epoxy Coating Functionalized with Inhibitor-Loaded Graphene Oxide Nanoribbons. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 220, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulyk, B.; Freitas, M.A.; Santos, N.F.; Mohseni, F.; Carvalho, A.F.; Yasakau, K.; Fernandes, A.; Bernardes, A.; Figueiredo, B.; Silva, R.; et al. A Critical Review on the Production and Application of Graphene and Graphene-Based Materials in Anti-Corrosion Coatings. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2022, 47, 309–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia, H.H.; Li, G.H.; Lan, Y.X.; Kunwar, R.; Kuo, L.Y.; Yeh, J.M.; Liu, W.R. Experimental and Theoretical Calculations of Fluorinated Few-Layer Graphene/Epoxy Composite Coatings for Anticorrosion Applications. Carbon 2024, 217, 118604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahryari, Z.; Yeganeh, M.; Gheisari, K.; Ramezanzadeh, B. A Brief Review of the Graphene Oxide-Based Polymer Nanocomposite Coatings: Preparation, Characterization, and Properties. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2021, 18, 945–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Zhang, M.; Cui, Y.; Bao, D.; Peng, J.; Gao, Y.; Lin, D.; Geng, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H. A Novel Polymer Composite Coating with High Thermal Conductivity and Unique Anti-Corrosion Performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 439, 135660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutapea, J.A.A.; Puspitasari, N.; Fahmi, M.Z.; Kurniawan, F. Comprehensive Review of Graphene Synthesis Techniques: Advancements, Challenges, and Future Directions. Micro 2025, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Cruz, A.; Ruiz-Hernández, A.R.; Becerra-Rojas, J.; García-Carvajal, O.Y.; Ayala-Cortés, A.; Martínez-Casillas, D.C. A Review of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Synthesis Methods for the Production of Graphene, Graphene Oxide and Reduced Graphene Oxide. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 14543–14578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzhanov, A.G. The Chemistry of Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. J. Mater. Chem. 2004, 14, 1779–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzhanov, A.G.; Sharivker, S.Y. Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis of Carbides, Nitrides, and Borides. In Materials Science of Carbides, Nitrides and Borides; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 205–222. [Google Scholar]

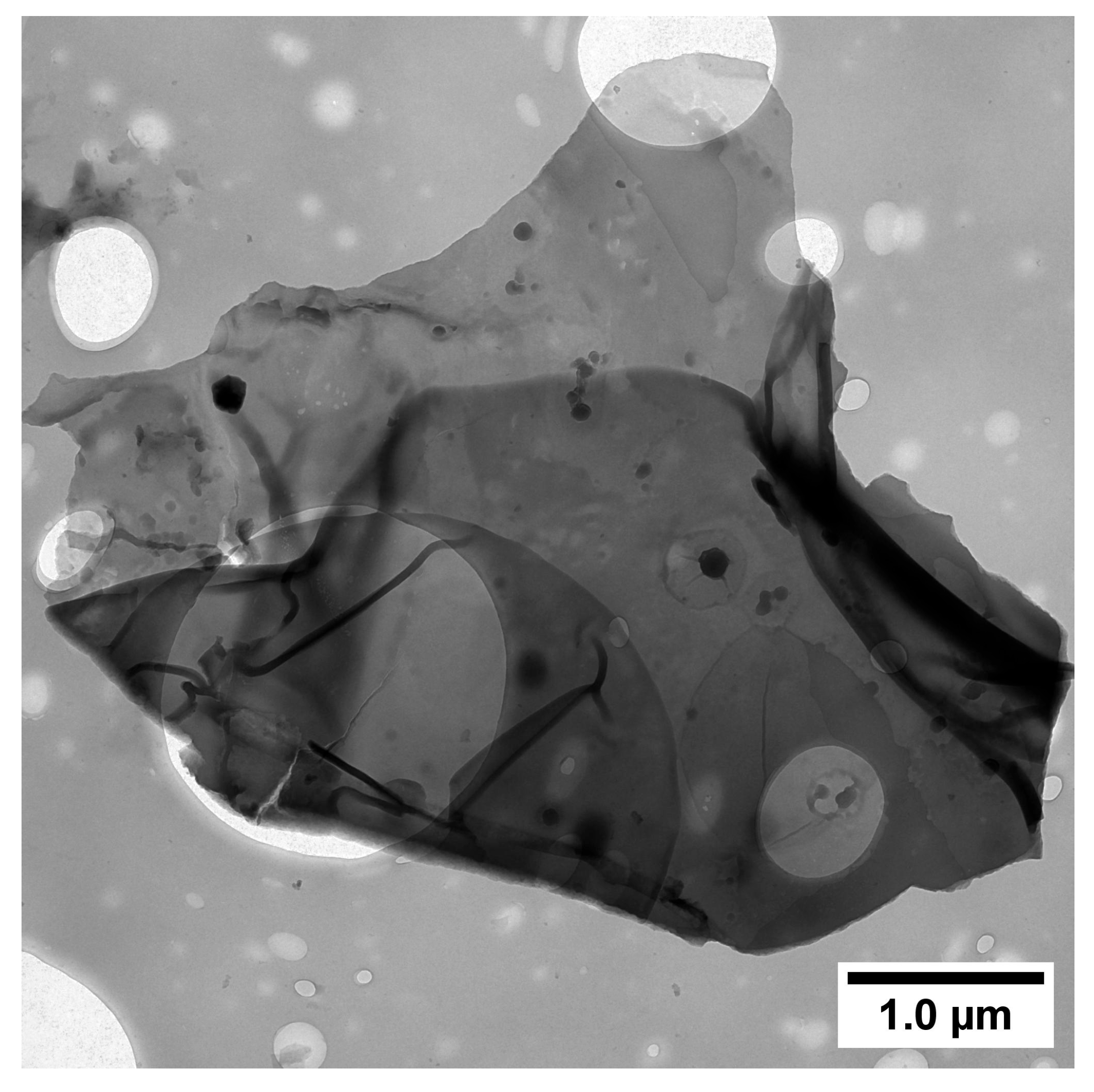

- Voznyakovskii, A.P.; Vozniakovskii, A.A.; Kidalov, S.V. New Way of Synthesis of Few-Layer Graphene Nanosheets by the Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis Method from Biopolymers. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozniakovskii, A.A.; Voznyakovskii, A.P.; Kidalov, S.V.; Osipov, V.Y. Structure and Paramagnetic Properties of Graphene Nanoplatelets Prepared from Biopolymers Using Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. J. Struct. Chem. 2020, 61, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voznyakovskii, A.P.; Neverovskaya, A.A.; Vozniakovskii, A.A.; Kidalov, S.V. A Quantitative Chemical Method for Determining the Surface Concentration of Stone–Wales Defects for 1D and 2D Carbon Nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

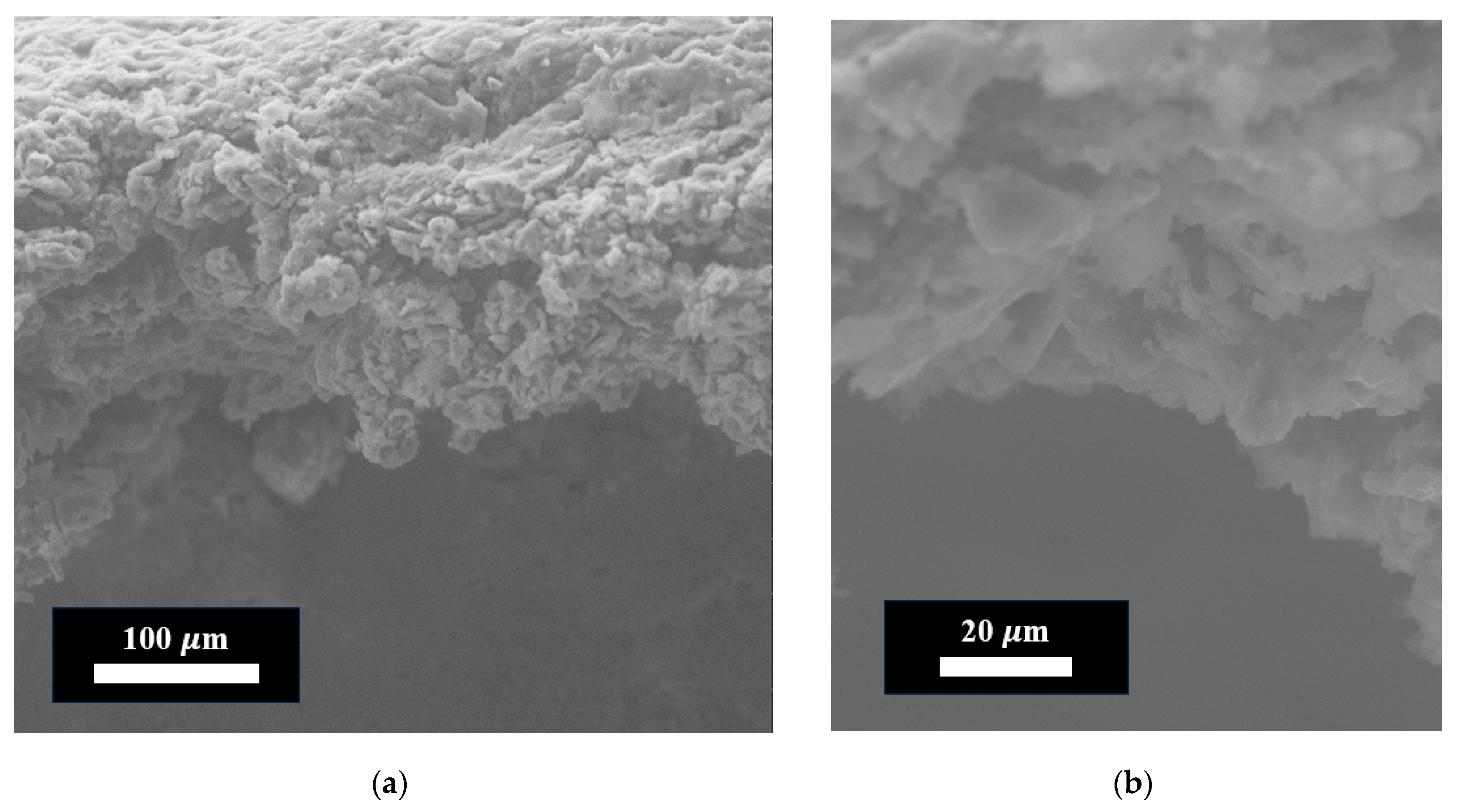

- Kidalov, S.V.; Voznyakovskii, A.P.; Vozniakovskii, A.A.; Titova, S.I.; Auchynnikau, Y.V. The Effect of Few-Layer Graphene on the Complex of Hardness, Strength, and Thermo-Physical Properties of Polymer Composite Materials Produced by Digital Light Processing (DLP) 3D Printing. Materials 2023, 16, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trikkaliotis, D.G.; Mitropoulos, A.C.; Kyzas, G.Z. Graphene Oxide Synthesis, Properties and Characterization Techniques: A Comprehensive Review. ChemEngineering 2021, 5, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjundappa, V.S.; Bommegowda, K.B.; Yallur, B.C.; Koppad, S.; Kudur, S.P. Efficient Strategies to Produce Graphene and Functionalized Graphene Materials: A Review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2023, 14, 100386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhametzhanov, M.N.; Sheichenko, V.I.; Ban’kovskii, A.I.; Rybalko, K.S.; Boryaev, K.I. Stizolin—A new sesquiterpene lactone from Stizolophus balsamita. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1969, 5, 49–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 527-1:2019; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties. Part 1: General Principles. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Santos, R.M.; Pimenta, A.; Botelho, G.; Machado, A.V. Influence of the Testing Conditions on the Efficiency and Durability of Stabilizers against ABS Photo-Oxidation. Polym. Test. 2013, 32, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorio, R.; Villanueva Díez, S.; Sánchez, A.; D’hooge, D.R.; Cardon, L. Influence of Different Stabilization Systems and Multiple Ultraviolet A (UVA) Aging/Recycling Steps on Physicochemical, Mechanical, Colorimetric, and Thermal-Oxidative Properties of ABS. Materials 2020, 13, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

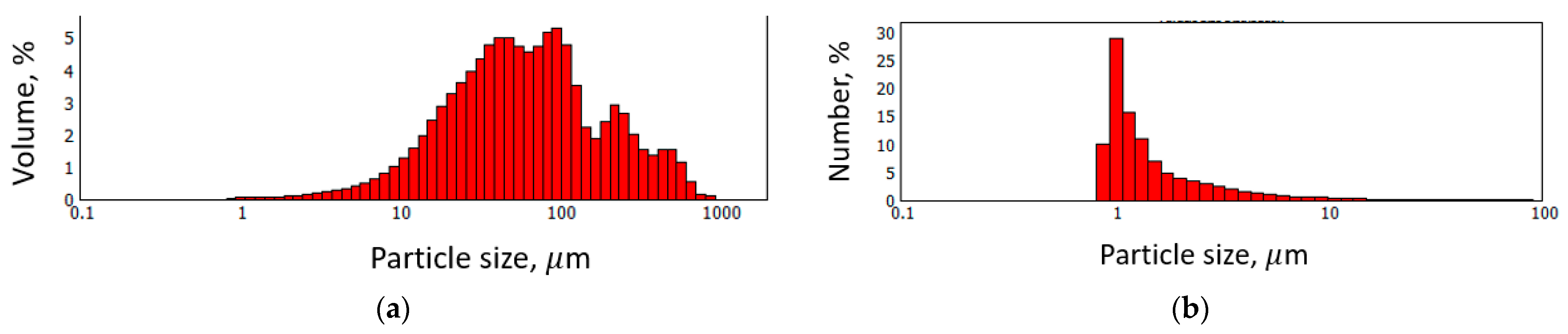

- Blott, S.J.; Croft, D.J.; Pye, K.; Saye, S.E.; Wilson, H.E. Particle Size Analysis by Laser Diffraction. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2004, 232, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

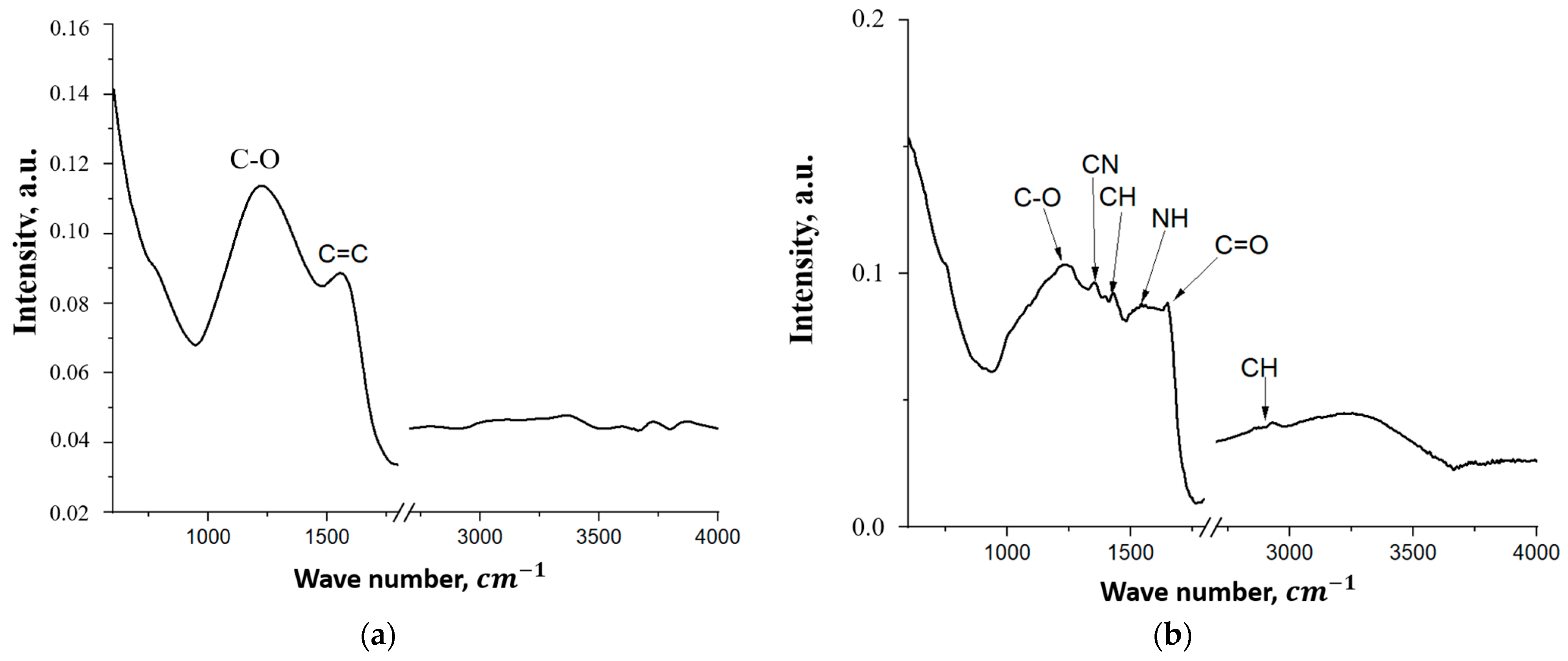

- Surekha, G.; Krishnaiah, K.V.; Ravi, N.; Suvarna, R.P. FTIR, Raman and XRD Analysis of Graphene Oxide Films Prepared by Modified Hummers Method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1495, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, K.B.H.; Sien, W.C.; Shahrom, M.S.B.R.; Hao, L.C.; Baderuliksan, N.Y.; Norzali, N.R. FTIR Spectroscopy Analysis of the Prepolymerization of Palm-Based Polyurethane. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2010, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

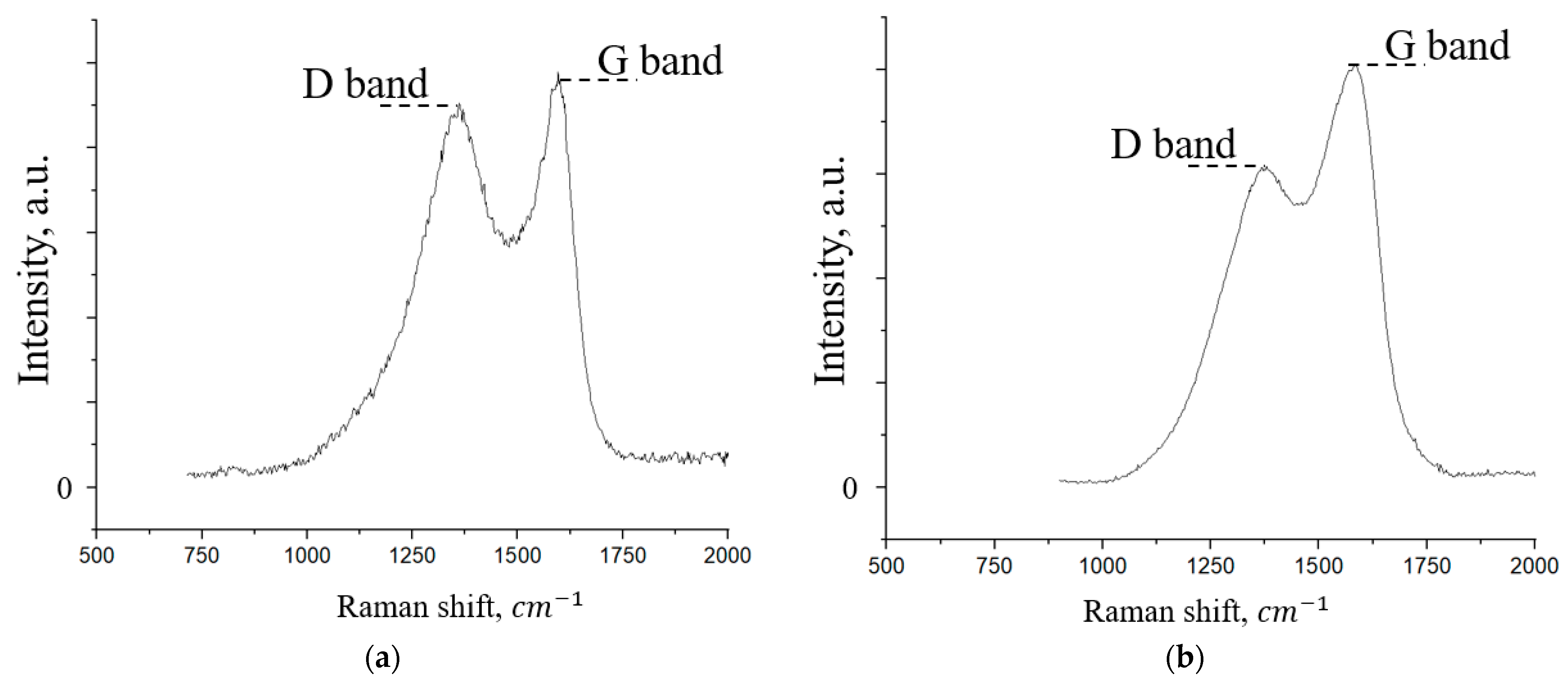

- Saito, R.; Hofmann, M.; Dresselhaus, G.; Jorio, A.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Raman Spectroscopy of Graphene and Carbon Nanotubes. Adv. Phys. 2011, 60, 413–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Chakraborty, B.; Sood, A.K. Raman Spectroscopy of Graphene on Different Substrates and Influence of Defects. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2008, 31, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonsalla, T.; Moore, A.L.; Meng, W.J.; Radadia, A.D.; Weiss, L. 3-D Printer Settings Effects on the Thermal Conductivity of Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS). Polym. Test. 2018, 70, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raney, K.; Lani, E.; Kalla, D.K. Experimental Characterization of the Tensile Strength of ABS Parts Manufactured by Fused Deposition Modeling Process. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 7956–7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassie, N.; Scott, G. Polymer Degradation and Stabilisation; CUP Archive: Cambridge, UK, 1988; p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- Piton, M.; Rivaton, A. Photo-Oxidation of ABS at Long Wavelengths (λ > 300 nm). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1997, 55, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaemy, M.; Scott, G. Mechanisms of Antioxidant Action: The Effectiveness of a Polymer-Bound UV Stabiliser for ABS in Relation to Its Method of Preparation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1981, 3, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-B.; Lin, M.-L.; Cong, X.; Liu, H.-N.; Tan, P.-H. Raman Spectroscopy of Graphene-Based Materials and Its Applications in Related Devices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 1822–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Samani, M.K.; Li, H.; Dong, L.; Zhang, Z.; Su, G.; Ye, L.; Chen, S.; Chen, K.; Pan, J.; et al. Tailoring the Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Graphene Film by Structural Engineering. Small 2018, 14, 1801346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.; Li, Z.X.; Li, Y.Q.; Hu, N.; Fu, S.-Y.; Novoselov, K.S. Graphene Film for Thermal Management: A Review. Nano Mater. Sci. 2021, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Nikkhah, M.; Ebrahimi, S. A Review on Graphene’s Light Stabilizing Effects for Reduced Photodegradation of Polymers. Crystals 2020, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

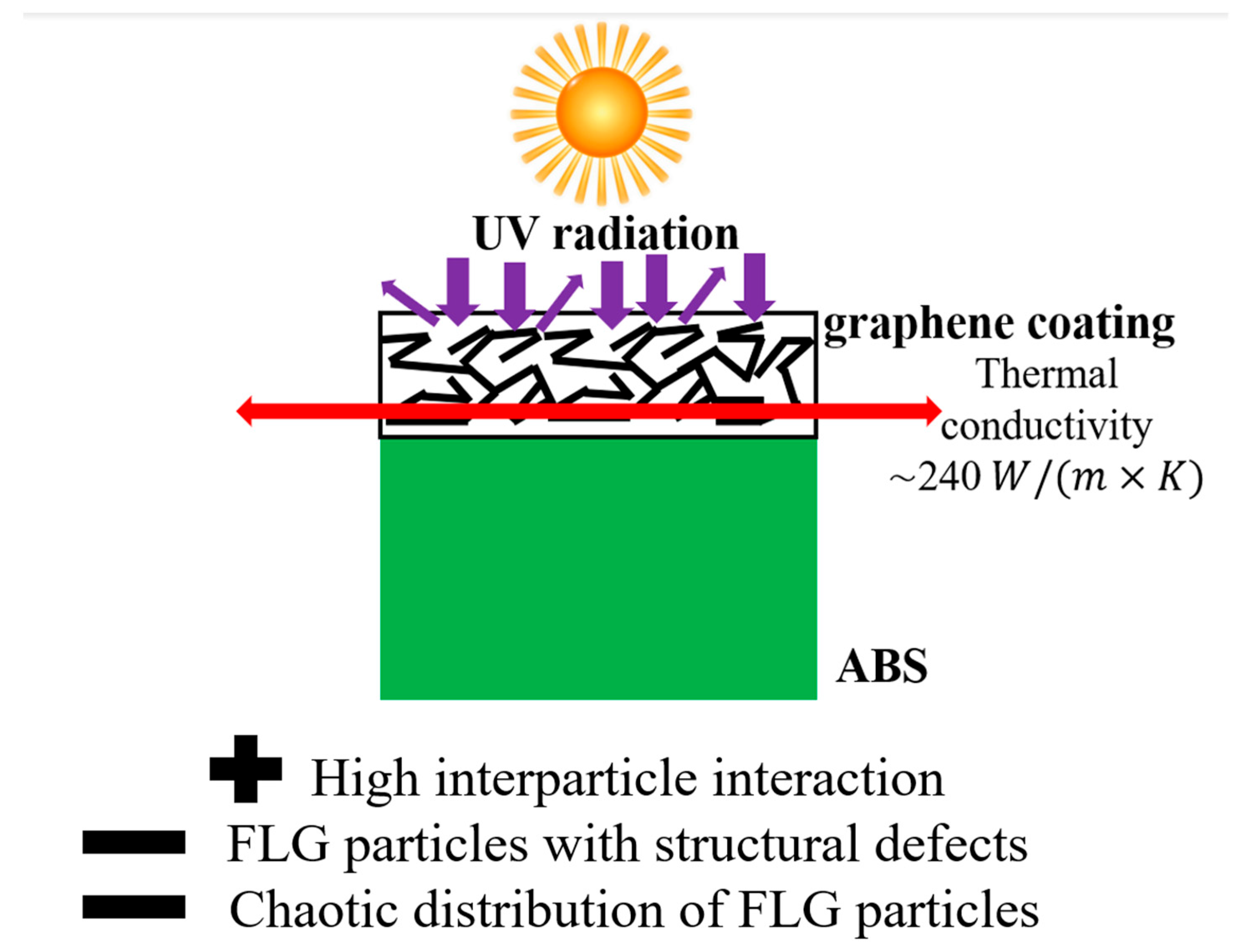

| Through-Plane Thermal Conductivity of ABS Substrate, W/(m × K) | In-Plane Thermal Conductivity of ABS Substrate, W/(m × K) | In-Plane Thermal Conductivity of FLG Coating, W/(m × K) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 244 ± 8 |

| Initial ABS | Initial ABS After UV Exposure | ABS + FLG Coating | ABS + FLG Coating After UV Exposure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile strength, MPa | 29 ± 1 | 19 ± 1 | 29 ± 1 | 30 ± 1 |

| Elongation at break, % | 7 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 7 ± 1 | 7 ± 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vozniakovskii, A.; Voznyakovskii, A.; Neverovskaya, A.; Podlozhnyuk, N.; Kidalov, S.; Auchynnikau, E. Synthesis of Few-Layer Graphene from Lignin and Its Application for the Creation of Thermally Conductive and UV-Protective Coatings. Materials 2025, 18, 5429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235429

Vozniakovskii A, Voznyakovskii A, Neverovskaya A, Podlozhnyuk N, Kidalov S, Auchynnikau E. Synthesis of Few-Layer Graphene from Lignin and Its Application for the Creation of Thermally Conductive and UV-Protective Coatings. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235429

Chicago/Turabian StyleVozniakovskii, Aleksei, Alexander Voznyakovskii, Anna Neverovskaya, Nikita Podlozhnyuk, Sergey Kidalov, and Evgeny Auchynnikau. 2025. "Synthesis of Few-Layer Graphene from Lignin and Its Application for the Creation of Thermally Conductive and UV-Protective Coatings" Materials 18, no. 23: 5429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235429

APA StyleVozniakovskii, A., Voznyakovskii, A., Neverovskaya, A., Podlozhnyuk, N., Kidalov, S., & Auchynnikau, E. (2025). Synthesis of Few-Layer Graphene from Lignin and Its Application for the Creation of Thermally Conductive and UV-Protective Coatings. Materials, 18(23), 5429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235429