Effectiveness of Ozone Treatment, Ultrasonic Treatment, and Ultraviolet Irradiation in Removing Candida albicans Adhered to Acrylic Resins Fabricated by Different Manufacturing Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fabrication of Resin Specimens

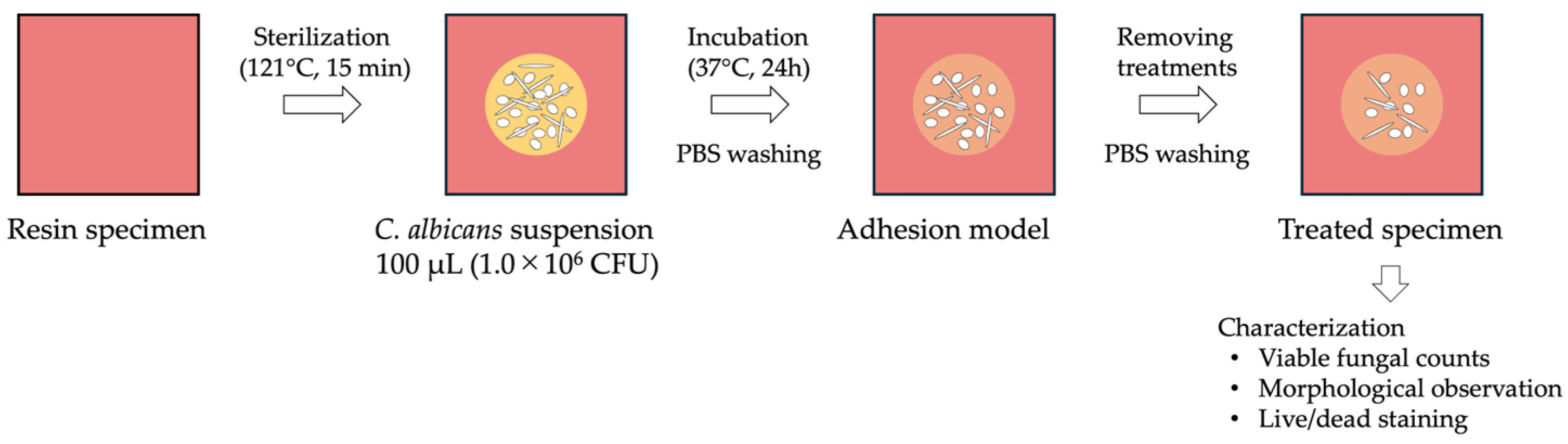

2.2. Preparation of Fungal Strains, Suspensions, and Adhesion Models

2.3. Treatments for the Adhesion Model (Table 1 and Figure 1)

- Immersion in tap water

- 2.

- Immersion in ozonated water

- 3.

- Ultrasonic cleaning

- 4.

- UV irradiation

- 5.

- Immersion in denture cleaner

- 6.

- Combination

| Code | Treatment Methods |

|---|---|

| Ctrl | Immersion in tap water for 5 min |

| OZ | Immersion in ozonated water for 5 min |

| US | Ultrasonic cleaning for 5 min |

| UV1 | UV (285 nm) irradiation for 1 min (distance 40 mm) |

| UV3 | UV (285 nm) irradiation for 3 min (distance 40 mm) |

| UV5 | UV (285 nm) irradiation for 5 min (distance 40 mm) |

| PO | Immersion in peroxide-type denture cleanser for 5 min |

| PK | Immersion in enzyme-type denture cleanser for 5 min |

| TP1 | Immersion in ozonated water for 5 min, and ultrasonic cleaning for 5 min, and UV irradiation for 1 min |

| TP3 | Immersion in ozonated water for 5 min, and ultrasonic cleaning for 5 min, and UV irradiation for 3 min |

| TP5 | Immersion in ozonated water for 5 min, and ultrasonic cleaning for 5 min, and UV irradiation for 5 min |

2.4. Evaluation of C. albicans Adhering to Resin Specimens

- Viable fungal counts (CFU/mL)

- 2.

- Scanning electron microscopy observation (SEM)

- 3.

- Fluorescence observation of live and dead C. albicans

- 4.

- Statistical analysis

3. Results

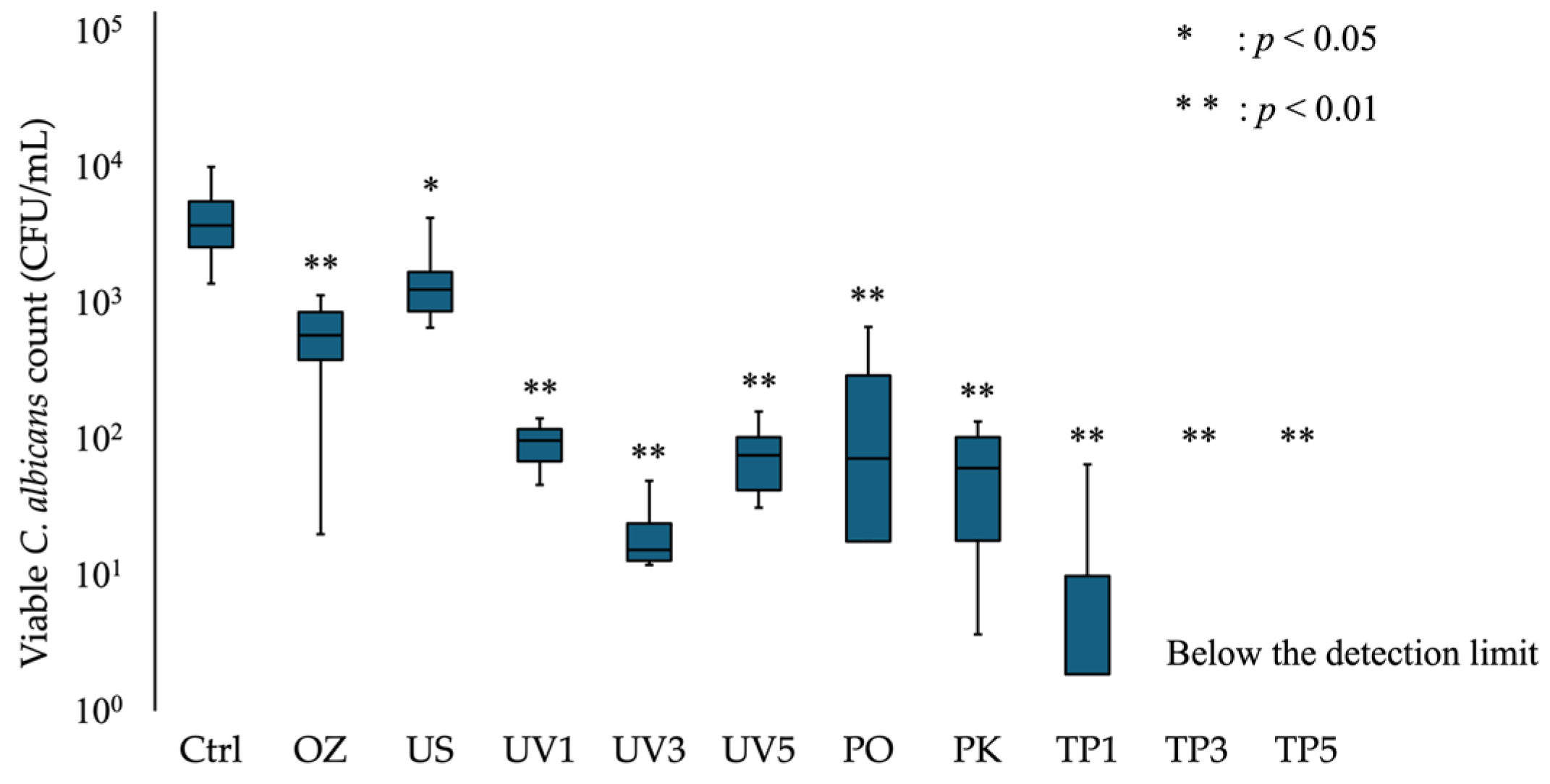

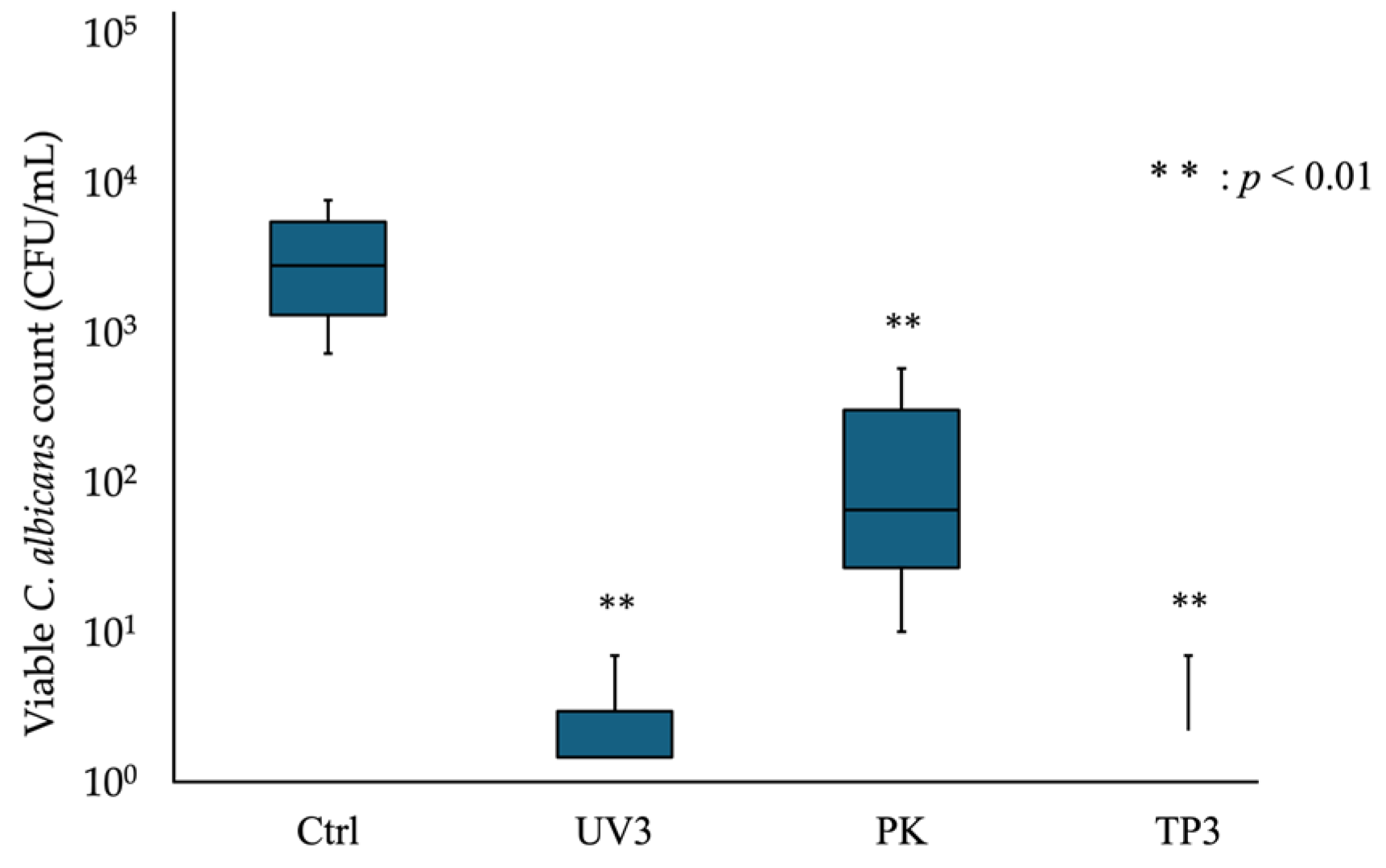

3.1. Viable Counts of C. albicans

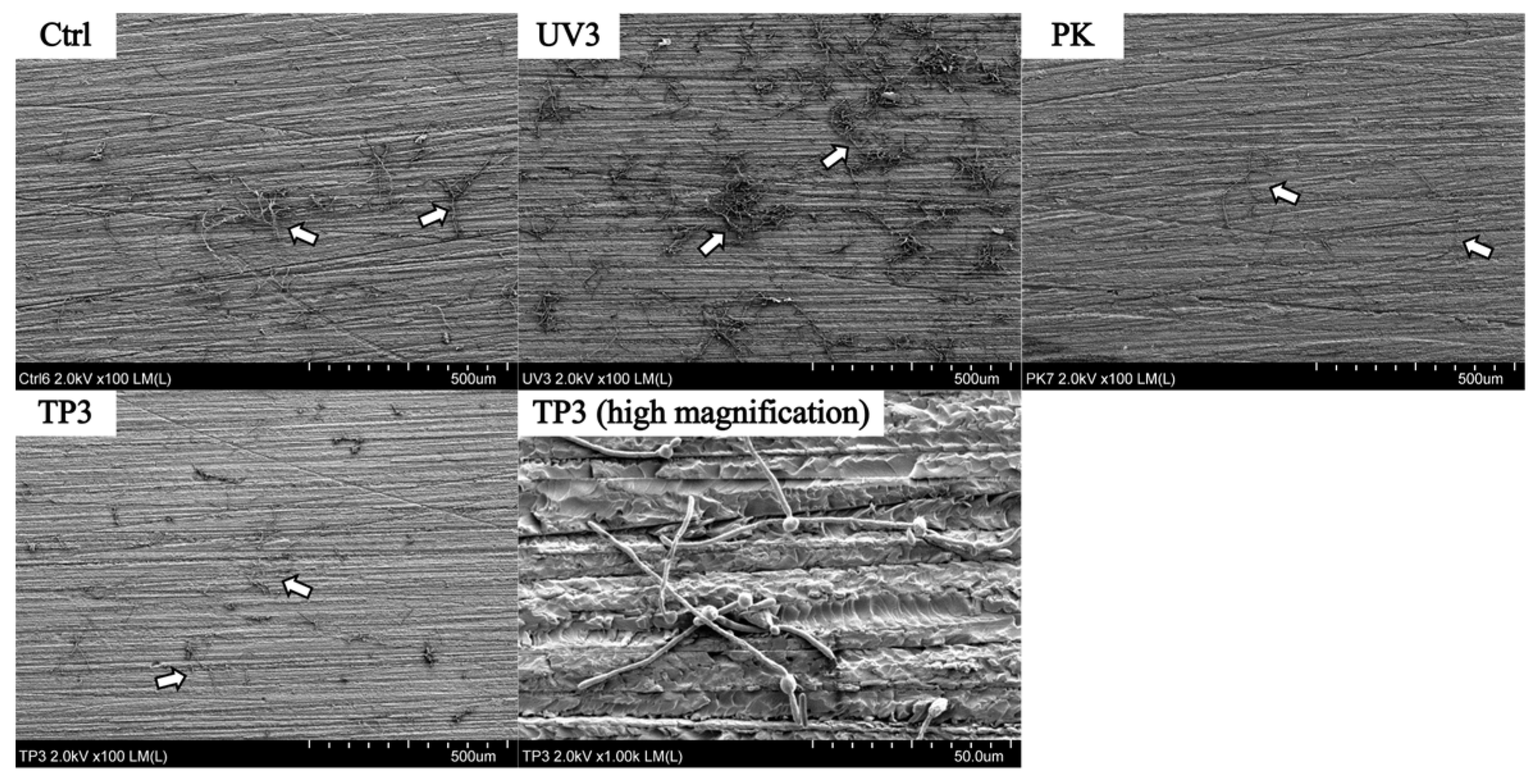

3.2. SEM Observation

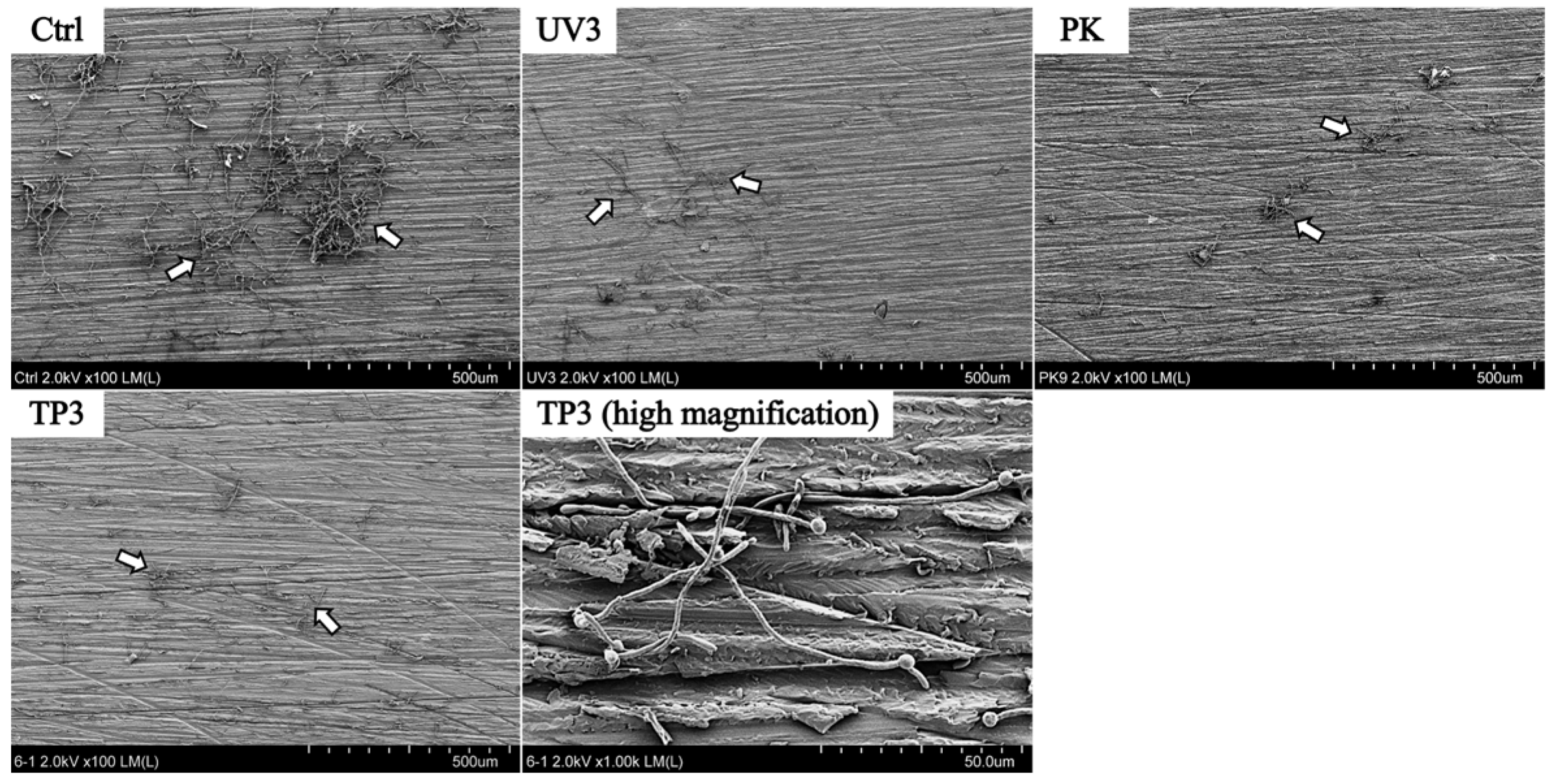

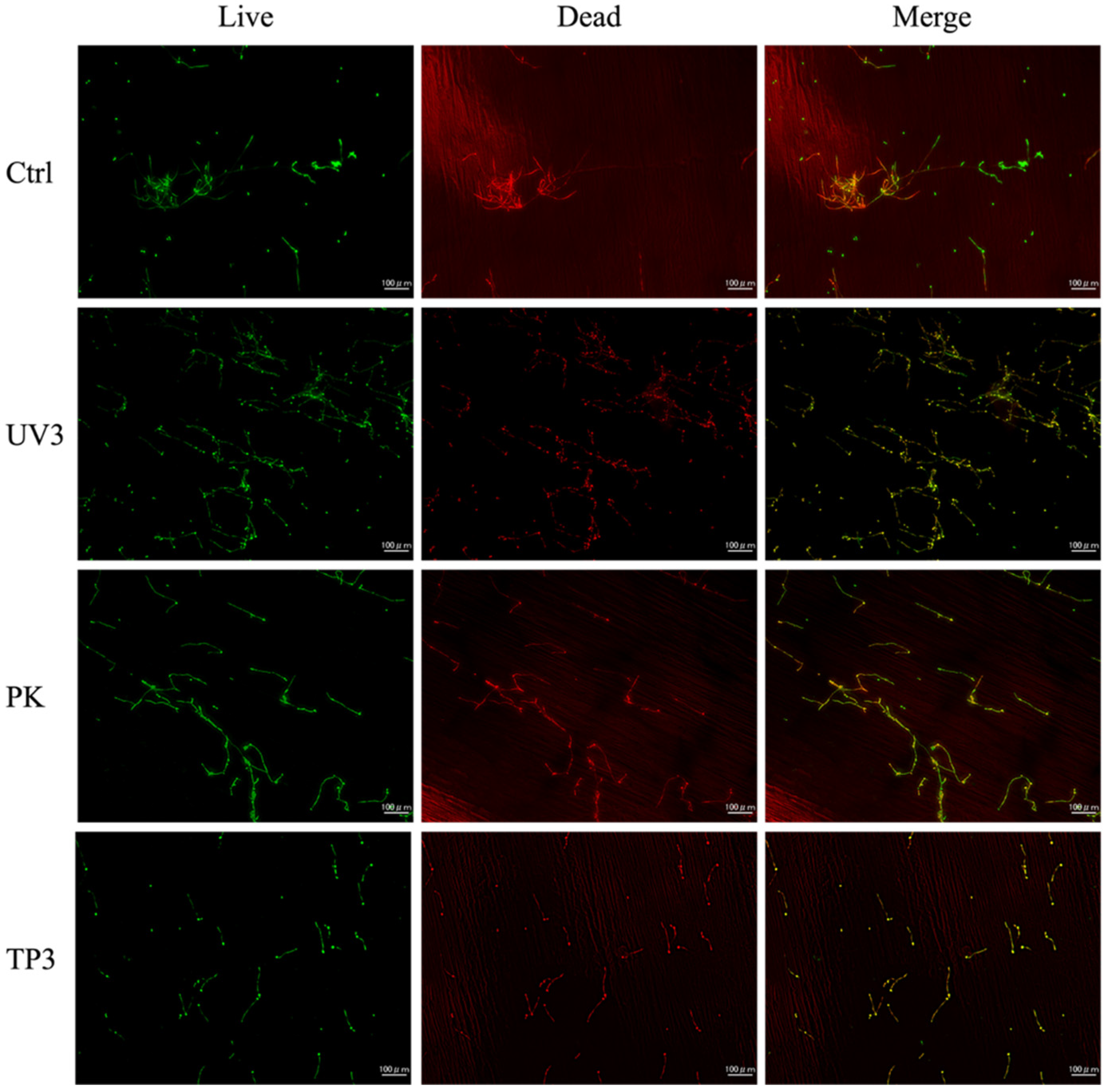

3.3. Fluorescence Observation of Viable and Dead C. albicans

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

References

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results 2024. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/assets/Files/WPP2024_Summary-of-Results.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Douglass, C.W.; Shih, A.; Ostry, L. Will there be a need for complete dentures in the United States in 2020? J. Prosthet. Dent. 2002, 87, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonas, P.; Milward, P.; McAndrew, R. Denture cleanliness and hygiene: An overview. Br. Dent. J. 2022, 233, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, M.S. Prosthodontic applications of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA): An update. Polymers 2020, 12, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfouzan, A.; Tuwaym, M.; Aldaghri, E.; Alojaymi, T.; Alotiabi, H.; Taweel, S.; Al-Otaibi, H.; Ali, R.; Alshehri, H.; Labban, N. Efficacy of denture cleansers on microbial adherence and surface topography of conventional and CAD/CAM-processed denture base resins. Polymers 2023, 15, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susewind, S.; Lang, R.; Hahnel, S. Biofilm formation and Candida albicans morphology on the surface of denture base materials. Mycoses 2015, 58, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murat, S.; Alp, G.; Alatali, C.; Uzun, M. In vitro evaluation of adhesion of Candida albicans on CAD/CAM PMMA-based polymers. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, E873–E879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalcanti, Y.W.; Wilson, M.; Lewis, M.; Williams, D.; Senna, P.M.; Del-Bel-Cury, A.A.; da Silva, W.J. Salivary pellicles equalise surfaces’ charges and modulate the virulence of Candida albicans biofilm. Arch. Oral Biol. 2016, 66, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, R.; Conrad, R.; Bullard, J.; Goodson, L.; Mehta, N.; Lech, S.; Loewy, Z. Evaluation of microbial flora found in previously worn prostheses from the northeast and southwest regions of the United States. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2010, 103, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, L.E.; Smith, K.; Williams, C.; Nile, C.J.; Lappin, D.F.; Bradshaw, D.; Lambert, M.; Robertson, D.P.; Bagg, J.; Hannah, V.; et al. Dentures are a reservoir for respiratory pathogens. J. Prosthodont. 2016, 25, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhan Kumar, S.; Natarajan, S.; Ks, S.; Sundarajan, S.K.; Natarajan, P.; Arockiam, A.S. Dentures and the oral microbiome: Unraveling the hidden impact on edentulous and partially edentulous patients—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid. Based Dent. 2025, 26, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andjelkovic, M.; Sojic, L.T.; Lemic, A.M.; Nikolic, N.; Kannosh, I.Y.; Milasin, J. Does the prevalence of periodontal pathogens change in elderly edentulous patients after complete denture treatment? J. Prosthodont. 2017, 26, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André, R.F.; Andrade, I.M.; Silva-Lovato, C.H.; Paranhos Hde, F.; Pimenta, F.C.; Ito, I.Y. Prevalence of mutans streptococci isolated from complete dentures and their susceptibility to mouthrinses. Braz. Dent. J. 2011, 22, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumi, Y.; Kagami, H.; Ohtsuka, Y.; Kakinoki, Y.; Haruguchi, Y.; Miyamoto, H. High correlation between the bacterial species in denture plaque and pharyngeal microflora. Gerodontology 2003, 20, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfern, J.; Tosheva, L.; Malic, S.; Butcher, M.; Ramage, G.; Verran, J. The denture microbiome in health and disease: An exploration of a unique community. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 75, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McReynolds, D.E.; Moorthy, A.; Moneley, J.O.; Jabra-Rizk, M.A.; Sultan, A.S. Denture stomatitis- An interdisciplinary clinical review. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 32, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayahara, M.; Kataoka, R.; Arimoto, T.; Tamaki, Y.; Yamaguchi, N.; Watanabe, Y.; Yamasaki, Y.; Miyazaki, T. Effects of surface roughness and dimorphism on the adhesion of Candida albicans to the surface of resins: Scanning electron microscope analyses of mode and number of adhesions. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2014, 5, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobile, C.; Johnson, A. Candida albicans biofilms and human disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 69, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniluk, T.; Tokajuk, G.; Stokowska, W.; Fiedoruk, K.; Sciepuk, M.; Zaremba, M.L.; Rozkiewicz, D.; Cylwik-Rokicka, D.; Kedra, B.A.; Anielska, I.; et al. Occurrence rate of oral Candida albicans in denture wearer patients. Adv. Med. Sci. 2006, 51, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ponde, N.O.; Lortal, L.; Ramage, G.; Naglik, J.R.; Richardson, J.P. Candida albicans biofilms and polymicrobial interactions. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 47, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, M.; Nobile, C.J. Candida albicans biofilms: Development, regulation, and molecular mechanisms. Microbes Infect. 2016, 18, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felton, D.; Cooper, L.; Duqum, I.; Minsley, G.; Guckes, A.; Haug, S.; Meredith, P.; Solie, C.; Avery, D.; Deal Chandler, N. Evidence-based guidelines for the care and maintenance of complete dentures: A publication of the American College of Prosthodontists. J. Prosthodont. 2011, 20, S1–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, K.; Kamikawa, Y.; Sugihara, K. In vitro and in vivo removal of oral Candida from the denture base. Gerodontology 2016, 33, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milward, P.; Katechia, D.; Morgan, M.Z. Knowledge of removable partial denture wearers on denture hygiene. Br. Dent. J. 2013, 215, E20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Liu, X.D.; Cai, Y. Effects of two peroxide enzymatic denture cleaners on Candida albicans biofilms and denture surface. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, A.; Idris, G.; Hajeer, M.; Alawer, K.; Cannon, R. Efficacy of removing Candida albicans from orthodontic acrylic bases: An in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasso, C.; Ribas, B.; Ferrisse, T.; de Oliveira, J.; Jorge, J. The antimicrobial activity of an antiseptic soap against Candida albicans and Streptococcus mutans single and dual-species biofilms on denture base and reline acrylic resins. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, Y.; Sato, Y.; Owada, G.; Minakuchi, S. Effectiveness of a combination denture-cleaning method versus a mechanical method: Comparison of denture cleanliness, patient satisfaction, and oral health-related quality of life. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2018, 62, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, T.W.; Burrow, M.F.; McGrath, C. Efficacy of ultrasonic home-care denture cleaning versus conventional denture cleaning: A randomised crossover clinical trial. J. Dent. 2024, 148, 105215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamio, A.; Barboza, A.; da Silva, M.; Soto, A.; de Andrade, J.; Duque, T.; da Cruz, A.; Mazzon, R.; Badaro, M. Disinfection strategies for poly(methyl methacrylate): Method sequence, solution concentration, and intraoral temperature on antimicrobial activity. Polymers 2025, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaypetch, R.; Rudrakanjana, P.; Tua-Ngam, P.; Tosrisawatkasem, O.; Thairat, S.; Tonput, P.; Tantivitayakul, P. Effects of two novel denture cleansers on multispecies microbial biofilms, stain removal and the denture surface: An in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faot, F.; Cavalcanti, Y.; Bertolini, M.; Pinto, L.; da Silva, W.; Cury, A. Efficacy of citric acid denture cleanser on the Candida albicans biofilm formed on poly(methyl methacrylate): Effects on residual biofilm and recolonization process. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latib, Y.; Owen, C.; Patel, M. Viability of Candida albicans in denture base resin after disinfection: A preliminary study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2018, 31, 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arita, M.; Nagayoshi, M.; Fukuizumi, T.; Okinaga, T.; Masumi, S.; Morikawa, M.; Kakinoki, Y.; Nishihara, T. Microbicidal efficacy of ozonated water against Candida albicans adhering to acrylic denture plates. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2005, 20, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binns, R.; Li, W.; Wu, C.D.; Campbell, S.; Knoernschild, K.; Yang, B. Effect of ultraviolet radiation on Candida albicans biofilm on poly(methylmethacrylate) resin. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, K.; Horinouchi, R.; Murakami, M.; Isii, M.; Kamashita, Y.; Shimotahira, N.; Suehiro, F.; Nishi, Y.; Murata, H.; Nishimura, M. The disinfectant effects of portable ultraviolet light devices and their application to dentures. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2024, 51, 104434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodacre, B.J.; Goodacre, C.J. Additive manufacturing for complete denture fabrication: A narrative review. J. Prosthodont. 2022, 31, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 20795-1:2013; Dentistry—Base Polymers—Part 1: Denture Base Polymers. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/62277.html (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Elvis, A.M.; Ekta, J.S. Ozone therapy: A clinical review. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2011, 2, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Yadav, A.K.; Wei, T.; Kang, P. Ozone disinfection of waterborne pathogens: A review of mechanisms, applications, and challenges. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 60709–60730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shichiri-Negoro, Y.; Tsutsumi-Arai, C.; Arai, Y.; Satomura, K.; Arakawa, S.; Wakabayashi, N. Ozone ultrafine bubble water inhibits the early formation of Candida albicans biofilms. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwawaki, Y.; Matsuda, T.; Kurahashi, K.; Honda, T.; Goto, T.; Ichikawa, T. Effect of water temperature during ultrasonic denture cleaning. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 61, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, P.C.; Andrade, I.M.; Peracini, A.; Souza-Gugelmin, M.C.; Silva-Lovato, C.H.; de Souza, R.F.; Paranhos Hde, F. The effectiveness of chemical denture cleansers and ultrasonic device in biofilm removal from complete dentures. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2011, 19, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y.; Seto, K.; Kamashita, Y.; Take, C.; Kurono, A.; Nagaoka, E. Examination of denture-cleaning methods based on the quantity of microorganisms adhering to a denture. Gerodontology 2012, 29, e259–e266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koujan, A.; Aggarwal, H.; Chen, P.H.; Li, Z.; Givan, D.A.; Zhang, P.; Fu, C.C. Evaluation of Candida albicans adherence to CAD-CAM milled, 3D-printed, and heat-cured PMMA resin and efficacy of different disinfection techniques: An in vitro study. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 32, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirowitz, A.; Rahmanov, A.; Shlomo, E.; Zelikman, H.; Dolev, E.; Sterer, N. Effect of denture base fabrication technique on Candida albicans adhesion in vitro. Materials 2021, 14, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fouzan, A.F.; Al-Mejrad, L.A.; Albarrag, A.M. Adherence of Candida to complete denture surfaces in vitro: A comparison of conventional and CAD/CAM complete dentures. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2017, 9, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, R.B.; Khoder, G.; Fayed, B.; Kedia, R.A.; Elkareimi, Y.; Alharbi, N. Influence of fabrication technique on adhesion and biofilm formation of Candida albicans to conventional, milled, and 3D-printed denture base resin materials: A comparative in vitro study. Polymers 2023, 15, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, T.; Alshanta, O.; Kean, R.; Bradshaw, D.; Pratten, J.; Williams, C.; Woodall, C.; Ramage, G.; Brown, J. Candida albicans as an essential “Keystone” component within polymicrobial oral biofilm models? Microorganisms 2021, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Andrade, I.; Cruz, P.; da Silva, C.; de Souza, R.; Paranhos, H.; Candido, R.; Marin, J.; de Souza-Gugelmin, M. Effervescent tablets and ultrasonic devices against Candida and mutans streptococci in denture biofilm. Gerodontology 2011, 28, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kaneko, C.; Sawada, T.; Ishikawa, T.; Miura, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Takemoto, S. Effectiveness of Ozone Treatment, Ultrasonic Treatment, and Ultraviolet Irradiation in Removing Candida albicans Adhered to Acrylic Resins Fabricated by Different Manufacturing Methods. Materials 2026, 19, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010053

Kaneko C, Sawada T, Ishikawa T, Miura T, Kobayashi T, Takemoto S. Effectiveness of Ozone Treatment, Ultrasonic Treatment, and Ultraviolet Irradiation in Removing Candida albicans Adhered to Acrylic Resins Fabricated by Different Manufacturing Methods. Materials. 2026; 19(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaneko, Chihiro, Tomofumi Sawada, Taichi Ishikawa, Toshitaka Miura, Takuya Kobayashi, and Shinji Takemoto. 2026. "Effectiveness of Ozone Treatment, Ultrasonic Treatment, and Ultraviolet Irradiation in Removing Candida albicans Adhered to Acrylic Resins Fabricated by Different Manufacturing Methods" Materials 19, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010053

APA StyleKaneko, C., Sawada, T., Ishikawa, T., Miura, T., Kobayashi, T., & Takemoto, S. (2026). Effectiveness of Ozone Treatment, Ultrasonic Treatment, and Ultraviolet Irradiation in Removing Candida albicans Adhered to Acrylic Resins Fabricated by Different Manufacturing Methods. Materials, 19(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010053