Broadband EMI Shielding Performance in Optically Transparent Flexible In2O3/Ag/In2O3 Thin Film Structures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Magnetron Sputtering IAI Structures

2.2. Scanning and Transmission Electron Microscopy, EDX, XRD Analysis and Atomic Force Microscopy of IAI Structures

2.3. Optoelectronic Properties

2.4. Measurements the Shielding Properties IAI Structures in the Range of 0.01–40 GHz

2.5. THz Time-Domain Spectroscopy (THz-TDS)

2.6. Mechanical and Chemical Stability Tests

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Features of IAI Structures

3.2. Optoelectronic Properties of IAI Structures

3.3. Spectroscopy of IAI Structures in Range 0.01–40 GHz

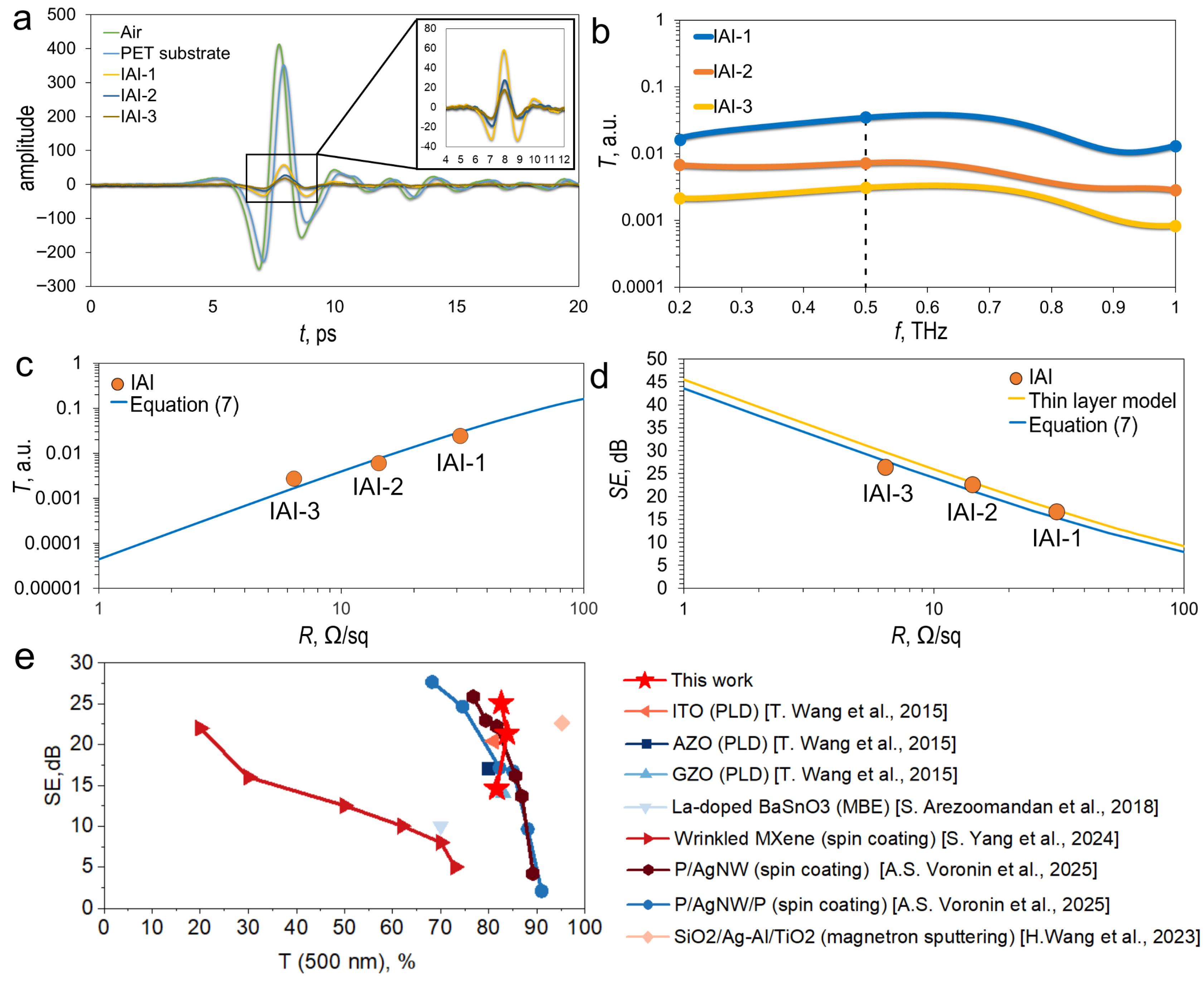

3.4. THz-TDS of IAI Structures

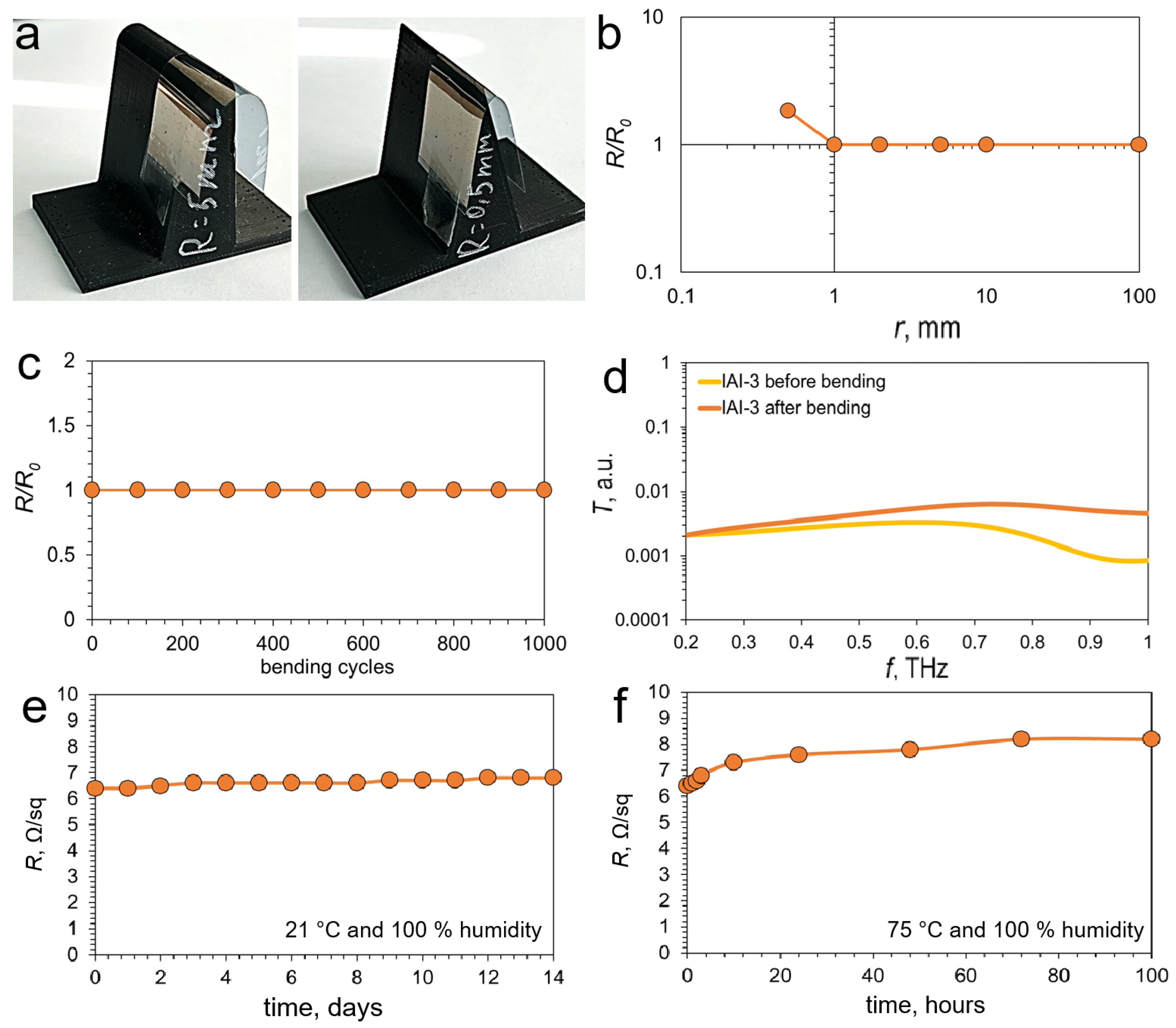

3.5. Mechanical, Chemical and Thermal Stability of IAI Structures

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OMO | Oxide/metal/oxide |

| IAI | In2O3/Ag/In2O3 |

| TCO | Transparent conductive oxide |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| THz-TDS | THz- time domain spectroscopy |

| rGO | Reduced Graphene Oxide |

| PEDOT:PSS | poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene): polystyrene sulfonate |

| VHF | Very High Frequency |

| EHF | Extremely High Frequency |

| ITO | Indium tin oxide |

| AZO | Aluminum zinc oxide |

| GZO | Gallium zinc oxide |

References

- Tan, D.; Jiang, C.; Li, Q.; Bi, S.; Wang, X.; Song, J. Development and current situation of flexible and transparent EM shielding materials. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 25603–25630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osipkov, A.; Makeev, M.; Konopleva, E.; Kudrina, N.; Gorobinskiy, L.; Mikhalev, P.; Ryzhenko, D.; Yurkov, G. Optically transparent and highly conductive electrodes for acousto-optical devices. Materials 2021, 14, 7178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronin, A.S.; Fadeev, Y.V.; Govorun, I.V.; Voloshin, A.S.; Tambasov, I.A.; Simunin, M.M.; Khartov, S.V. A transparent radio frequency shielding coating obtained using a self-organized template. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2021, 47, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.; Sarto, M.S.; Tamburrano, A. Shielding performances of ITO transparent windows: Theoretical and experimental characterization. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility—EMC Europe, Hamburg, Germany, 8–12 September 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Hyeong, S.-K.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S.-K.; Lee, J.-H.; Yu, H.K. Transparent and Flexible Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Film Using ITO Nanobranches by Internal Scattering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 61413–61421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Gao, J.; Dong, Y.; Li, K.; Shan, G.; Yang, S.; Li, R.K.-Y. Flexible transparent PES/silver nanowires/PET sandwich-structured film for high-efficiency electromagnetic interference shielding. Langmuir 2012, 28, 7101–7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Lee, H.; Ha, I.; Cho, H.; Kim, K.K.; Kwon, J.; Won, P.; Hong, S.; Ko, S.H. Highly stretchable and transparent electromagnetic interference shielding film based on silver nanowire percolation network for wearable electronics applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 44609–44616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronin, A.S.; Bril, I.I.; Fadeev, Y.V.; Pavlikov, A.Y.; Simunin, M.M.; Volochaev, M.N.; Govorun, I.V.; Podshivalov, I.V.; Makeev, M.O.; Mikhalev, P.A.; et al. Optical, electrical and EMI shielding properties of AgNW thin films. Tech. Phys. 2025, 95, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontorovich, M.I.; Astrakhan, M.I.; Akimov, V.P.; Fersman, G.A. Electrodynamics of Mesh Structures; Izdatel Radio Sviaz: Moscow, Russia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, C.; Wu, K.; Chong, H.; Ye, H. Transparent Conductive Oxides and Their Applications in Near Infrared Plasmonics. Phys. Status Solidi A 2019, 216, 1700794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menamparambath, M.M.; Yang, K.; Kim, H.H.; Bae, O.S.; Jeong, M.S.; Choi, J.-Y.; Baik, S. Reduced haze of transparent conductive films by smaller diameter silver nanowires. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 465706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deignan, G.; Goldthorpe, I.A. The dependence of silver nanowire stability on network composition and processing parameters. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 35590–35597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Ji, G. Multifunctional Integrated Transparent Film for Efficient Electromagnetic Protection. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Yan, Z.; Fan, J.; Cai, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, X. Highly Uniform and Stable Transparent Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Film Based on Silver Nanowire–PEDOT:PSS Composite for High Power Microwave Shielding. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2021, 306, 2000607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Su, M.; Yang, D.; Han, G.; Feng, Y.; Wang, B.; Ma, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, C.; Shen, C. Flexible MXene/Silver Nanowire-Based Transparent Conductive Film with Electromagnetic Interference Shielding and Electro-Photo-Thermal Performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 40859–40869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ji, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Z.; Tan, J.; Guo, L.J. Highly Transparent and Broadband Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Based on Ultrathin Doped Ag and Conducting Oxides Hybrid Film Structures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 11782–11791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Yang, Z.; Xu, J.; Dong, J. Research on optical transmittance and electromagnetic shielding effectiveness of TiO2/Cu/TiO2 multilayer film. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2025, 36, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, S.; Li, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J. Transparent and hard TiO2/Au electromagnetic shielding antireflection coatings on aircraft canopy PMMA organic glass. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 658, 159830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, C.-F.; Huang, S.; Sun, T.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Z. A new method for fabricating ultrathin metal films as scratch-resistant flexible transparent electrodes. J. Mater. 2015, 1, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gao, P.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Huang, F.; Ye, J. Optimizing ultrathin Ag films for high performance oxide-metal-oxide flexible transparent electrodes through surface energy modulation and template-stripping procedures. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, W.; Bae, T.-S.; Lee, S.-G.; Mun, C.W.; Lee, S.; Yu, H.; Lee, G.-H.; Song, M.; Yun, J. Stable ultrathin partially oxidized copper film electrode for highly efficient flexible solar cells. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Park, J.H.; Choi, D.H.; Jang, H.S.; Lee, J.H.; Park, H.J.; Choi, J.I.; Ju, D.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, D. ITO/Au/ITO multilayer thin films for transparent conducting electrode applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 254, 1524–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Rose, A.; Kwon, S.J.; Jeon, Y.; Cho, E.-S. Rapid photonic curing effects of xenon flash lamp on ITO–Ag–ITO multilayer electrodes for high throughput transparent electronics. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.; He, Z.; Zhu, K. Improved performance of AZO/Ag/AZO transparent conductive films by inserting an ultrathin Ti layer. Mater. Lett. 2024, 356, 135615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmedov, A.K.; Abduev, A.K.; Kanevsky, V.M.; Muslimov, A.E.; Asvarov, A.S. Low-Temperature Fabrication of High-Performance and Stable GZO/Ag/GZO Multilayer Structures for Transparent Electrode Applications. Coatings 2020, 10, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansåker, P.C.; Backholm, J.; Niklasson, G.A.; Granqvist, C.G. TiO2/Au/TiO2 multilayer thin films: Novel metal-based transparent conductors for electrochromic devices. Thin Solid Film. 2009, 518, 1225–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Han, L.; Cao, Z.; Lu, Z.; Tan, J. High-Performance Transparent Ultrabroadband Electromagnetic Radiation Shielding from Microwave toward Terahertz. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 49487–49499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, C.; Zhang, C.; Lu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Yuan, J.; Tan, J.; Guo, L.J. High-Performance Transparent Broadband Microwave Absorbers. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2101714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, L.; Ji, C.; Ye, Z.; Alsaab, N.; Yang, M.; Hu, Y.; Chen, P.-Y.; Guo, L.J. Functional plastic films: Nano-engineered composite based flexible microwave antennas with near-unity relative visible transmittance. Light Adv. Manuf. 2024, 5, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1003-21; Standard Test Method for Haze and Luminous Transmittance of Transparent Plastics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Maniyara, R.; Mkhitaryan, V.; Chen, T.; Chen, T.L.; Ghosh, D.S.; Pruneri, V. An antireflection transparent conductor with ultralow optical loss (<2%) and electrical resistance (<6 Ωsq−1). Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Qu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q. Effects of Al-doping concentration on the structure and electromagnetic shielding properties of transparent Ag thin films. Opt. Mater. 2023, 135, 113353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Su, W.; Wang, R.; Xu, X.; Zhang, F. Properties of thin silver films with different thickness. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2009, 41, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pana, I.; Parau, A.C.; Dinu, M.; Kiss, A.E.; Constantin, L.R.; Vitelaru, C. Optical Properties and Stability of Copper Thin Films for Transparent Thermal Heat Reflectors. Metals 2022, 12, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, J.S.; Gstrein, F.; O’Brien, K.P.; Clarke, J.S.; Gall, D. Electron scattering at surfaces and grain boundaries in Cu thin films and wires. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 235423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Islam, M.M.; Meitzner, R.; Schubert, U.S.; Hoppe, H. Introduction of a Novel Figure of Merit for the Assessment of Transparent Conductive Electrodes in Photovoltaics: Exact and Approximate Form. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2100875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronin, A.S.; Fadeev, Y.V.; Ivanchenko, F.S.; Dobrosmyslov, S.S.; Simunin, M.M.; Govorun, I.V.; Podshivalov, I.V.; Mikhalev, P.A.; Makeev, M.O.; Damaratskiy, I.A.; et al. Waste-free self-organized process manufacturing transparent conductive mesh and microflakes in closed cycle for broadband electromagnetic shielding and heater application. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2025, 36, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Su, J.; Liang, H.; Hu, K. Effect of different superimposed structures on the transparent electromagnetic interference shielding performance of graphene. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128, 185102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Oh, J.-S.; Kim, M.-G.; Jang, W.; Wang, M.; Kim, Y.; Seo, H.W.; Kim, Y.C.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, Y.; et al. Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) Transparent Shielding of Reduced Graphene Oxide (RGO) Interleaved Structure Fabricated by Electrophoretic Deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 17647–17653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, S.W. Ultra-bendable and durable Graphene–Urethane composite/silver nanowire film for flexible transparent electrodes and electromagnetic-interference shielding. Compos. Part B 2019, 177, 107406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.G.; Choi, J.H.; Choi, D.-K.; Kim, S.W. Highly Bendable and Durable Transparent Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Film Prepared by Wet Sintering of Silver Nanowires. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 29730–29740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.-H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.-W. Transparent and flexible film for shielding electromagnetic interference. Mater. Des. 2016, 89, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronin, A.S.; Fadeev, Y.V.; Makeev, M.O.; Mikhalev, P.A.; Osipkov, A.S.; Provatorov, A.S.; Ryzhenko, D.S.; Yurkov, G.Y.; Simunin, M.M.; Karpova, D.V.; et al. Low Cost Embedded Copper Mesh Based on Cracked Template for Highly Durability Transparent EMI Shielding Films. Materials 2022, 15, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voronin, A.S.; Fadeev, Y.V.; Ivanchenko, F.S.; Dobrosmyslov, S.S.; Makeev, M.O.; Mikhalev, P.A.; Osipkov, A.S.; Damaratsky, I.A.; Ryzhenko, D.S.; Yurkov, G.Y.; et al. Original concept of cracked template with controlled peeling of the cells perimeter for high performance transparent EMI shielding films. Surf. Interfaces 2023, 38, 102793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.V.; Nguyen, D.D.; Nguyen, A.T.; Hofmann, M.; Hsieh, Y.-P.; Kan, H.-C.; Hsu, C.C. Electromagnetic Interference Shielding by Transparent Graphene/Nickel Mesh Films. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 7474–7481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, D.; Hama, Y.; Miyachi, K.; Kishiyama, Y. Research of Transparent RIS Technology toward 5G evolution & 6G. NTT Tech. Rev. 2021, 19, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.A. Simple Formulas for Estimating the Microwave Shielding Effectiveness of Ec-Coated Optical Windows. In Proceedings of the SPIE 1989 Technical Symposium on Aerospace Sensing, Orlando, FL, USA, 17–31 March 1989; pp. 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, D.; He, C.; Liu, C.; Shen, C. Flexible hydrophobic 2D Ti3C2Tx-based transparent conductive film with multifunctional self-cleaning, electromagnetic interference shielding and joule heating capacities. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 201, 108531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wanga, Z.; Song, R.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhang, B.; Lv, H.; Wua, Z.; He, D. Flexible and transparent graphene/silver-nanowires composite film for high electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness. Sci. Bull. 2019, 64, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhong, H.; Liu, N.; Liu, Y.; Lin, J.; Jin, P. In Situ Surface Oxidized Copper Mesh Electrodes for High-Performance Transparent Electrical Heating and Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2018, 4, 1800156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Yoon, H.G.; Kim, S.W. Extremely Robust and Reliable Transparent Silver Nanowire-Mesh Electrode with Multifunctional Optoelectronic Performance through Selective Laser Nanowelding for Flexible Smart Devices. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2021, 23, 2001310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Lin, J.; Liu, Y.; Fu, H.; Ma, Y.; Jin, P.; Tan, J. Crackle template based metallic mesh with highly homogeneous light transmission for high performance transparent EMI shielding. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronin, A.S.; Fadeev, Y.V.; Govorun, I.V.; Podshivalov, I.V.; Simunin, M.M.; Tambasov, I.A.; Karpova, D.V.; Smolyarova, T.E.; Lukyanenko, A.V.; Karacharov, A.A.; et al. Cu–Ag and Ni–Ag meshes based on cracked template as efficient transparent electromagnetic shielding coating with excellent mechanical performance. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 14741–14762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassarab, V.V.; Shalygin, V.A.; Shakhmin, A.A.; Kropotov, G.I. Spectroscopy of ITO Films in Optical and Terahertz Spectral Ranges. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zalkovskij, M.; Iwaszczuk, K.; Lavrinenko, A.V.; Naik, G.V.; Kim, J.; Boltasseva, A.; Jepsen, P.U. Ultrabroadband terahertz conductivity of highly doped ZnO and ITO. Opt. Mater. Express 2015, 5, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arezoomandan, S.; Prakash, A.; Chanana, A.; Yue, J.; Mao, J.; Blair, S.; Nahata, A.; Jalan, B.; Sensale-Rodriguez, B. THz characterization and demonstration of visible-transparent/terahertz-functional electromagnetic structures in ultra-conductive La-doped BaSnO3 Films. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Liang, Y.; Wen, K.; Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, P.; Huang, X. Demonstration of Tunable Shielding Effectiveness in GHz and THz Bands for Flexible Graphene/Ion Gel/Graphene Film. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lin, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Yang, R.; Chen, Z.; Jia, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Cao, Z.; Zhu, H.; et al. Stretchable, Transparent, and Ultra-Broadband Terahertz Shielding Thin Films Based on Wrinkled MXene Architectures. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Xie, P.; Wan, H.; Ding, T.; Liu, M.; Xie, J.; Li, E.; Chen, X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Ultrathin MXene assemblies approach the intrinsic absorption limit in the 0.5–10 THz band. Nat. Photon 2023, 17, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronin, A.; Bril’, I.; Pavlikov, A.; Makeev, M.; Mikhalev, P.; Parshin, B.; Fadeev, Y.; Khodzitsky, M.; Simunin, M.; Khartov, S. THz Shielding Properties of Optically Transparent PEDOT:PSS/AgNW Composite Films and Their Sandwich Structures. Polymers 2025, 17, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przewłoka, A.; Smirnov, S.; Nefedova, I.; Krajewska, A.; Nefedov, I.S.; Demchenko, P.S.; Zykov, D.V.; Chebotarev, V.S.; But, D.B.; Stelmaszczyk, K.; et al. Characterization of Silver Nanowire Layers in the Terahertz Frequency Range. Materials 2021, 14, 7399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, M.; Cooke, D.G.; Sherstan, C.; Hajar, M.; Freeman, M.R.; Hegmann, F.A. Terahertz conductivity of thin gold films at the metal-insulator percolation transition. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 125408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.-P.; Lu, H.-I.; Lin, C.-K. Conductive Characteristics of Indium Tin Oxide Thin Film on Polymeric Substrate under Long-Term Static Deformation. Coatings 2018, 8, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Xua, J.; Huang, J.; Yang, Y.; Tan, R.; Chen, G.; Fang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Song, W. Robust ultrathin and transparent AZO/Ag-SnOx/AZO on polyimide substrate for flexible thin film heater with temperature over 400 °C. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 48, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| OMO Type | Rs, Ω/sq | TIAI+PET (500 nm), % | TIAI (500 nm), % | Haze, % | FoM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAI-1 | 31.4 ± 2.5 | 71.46 | 81.65 | 0.83 | 56.1 |

| IAI-2 | 14.3 ± 1.5 | 73.35 | 83.81 | 0.87 | 143.8 |

| IAI-3 | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 72.28 | 82.59 | 1.04 | 293.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Voronin, A.S.; Nedelin, S.V.; Zolotovsky, N.A.; Tambasov, I.A.; Makeev, M.O.; Mikhalev, P.A.; Parshin, B.A.; Buryanskaya, E.L.; Simunin, M.M.; Govorun, I.V.; et al. Broadband EMI Shielding Performance in Optically Transparent Flexible In2O3/Ag/In2O3 Thin Film Structures. Materials 2025, 18, 5393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235393

Voronin AS, Nedelin SV, Zolotovsky NA, Tambasov IA, Makeev MO, Mikhalev PA, Parshin BA, Buryanskaya EL, Simunin MM, Govorun IV, et al. Broadband EMI Shielding Performance in Optically Transparent Flexible In2O3/Ag/In2O3 Thin Film Structures. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235393

Chicago/Turabian StyleVoronin, Anton S., Sergey V. Nedelin, Nikita A. Zolotovsky, Igor A. Tambasov, Mstislav O. Makeev, Pavel A. Mikhalev, Bogdan A. Parshin, Evgenia L. Buryanskaya, Mikhail M. Simunin, Ilya V. Govorun, and et al. 2025. "Broadband EMI Shielding Performance in Optically Transparent Flexible In2O3/Ag/In2O3 Thin Film Structures" Materials 18, no. 23: 5393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235393

APA StyleVoronin, A. S., Nedelin, S. V., Zolotovsky, N. A., Tambasov, I. A., Makeev, M. O., Mikhalev, P. A., Parshin, B. A., Buryanskaya, E. L., Simunin, M. M., Govorun, I. V., Podshivalov, I. V., Bril`, I. I., Khodzitskiy, M. K., & Khartov, S. V. (2025). Broadband EMI Shielding Performance in Optically Transparent Flexible In2O3/Ag/In2O3 Thin Film Structures. Materials, 18(23), 5393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235393