Laser Powder Bed Fusion of 25CrMo4 Steel: Effect of Process Parameters on Metallurgical and Mechanical Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

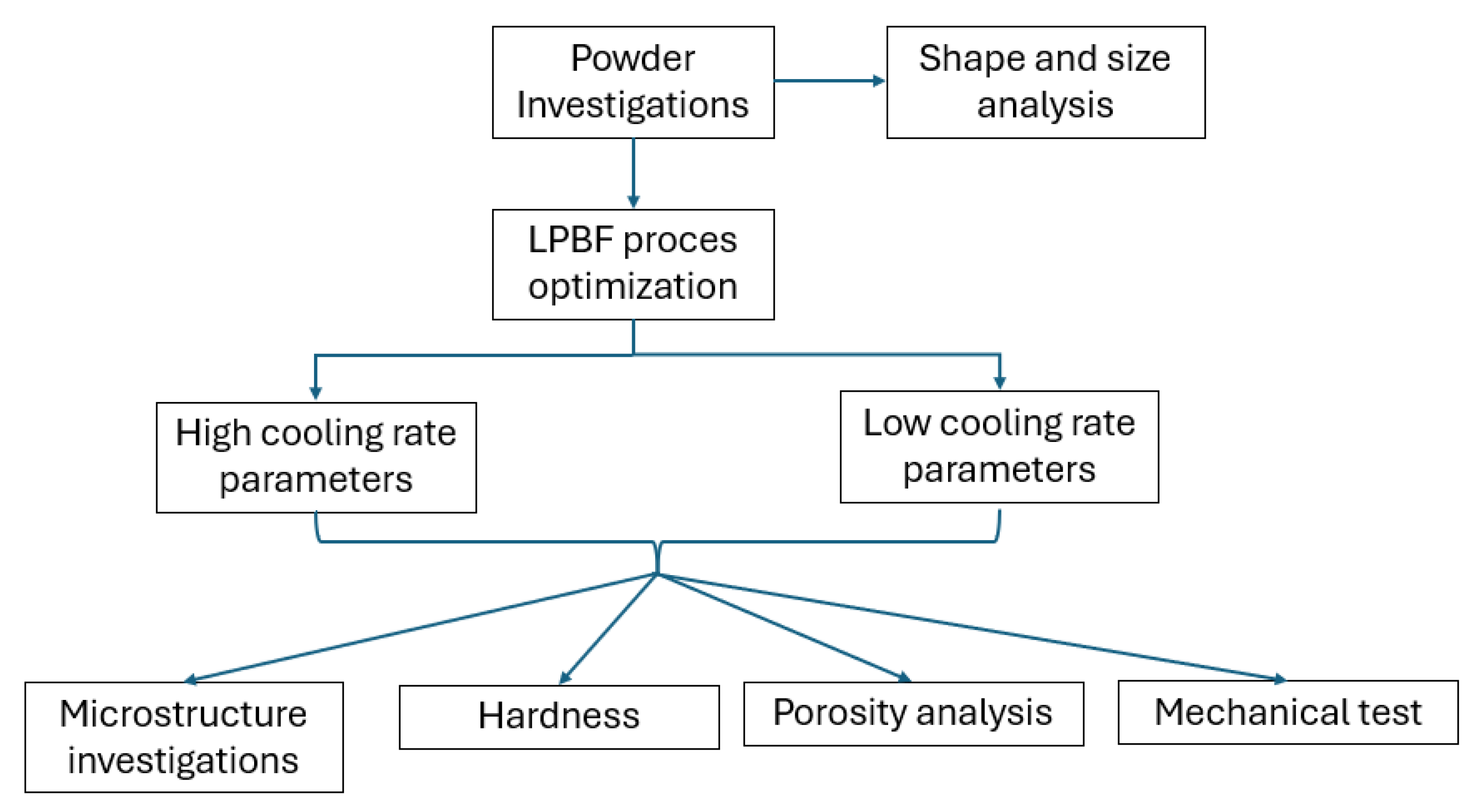

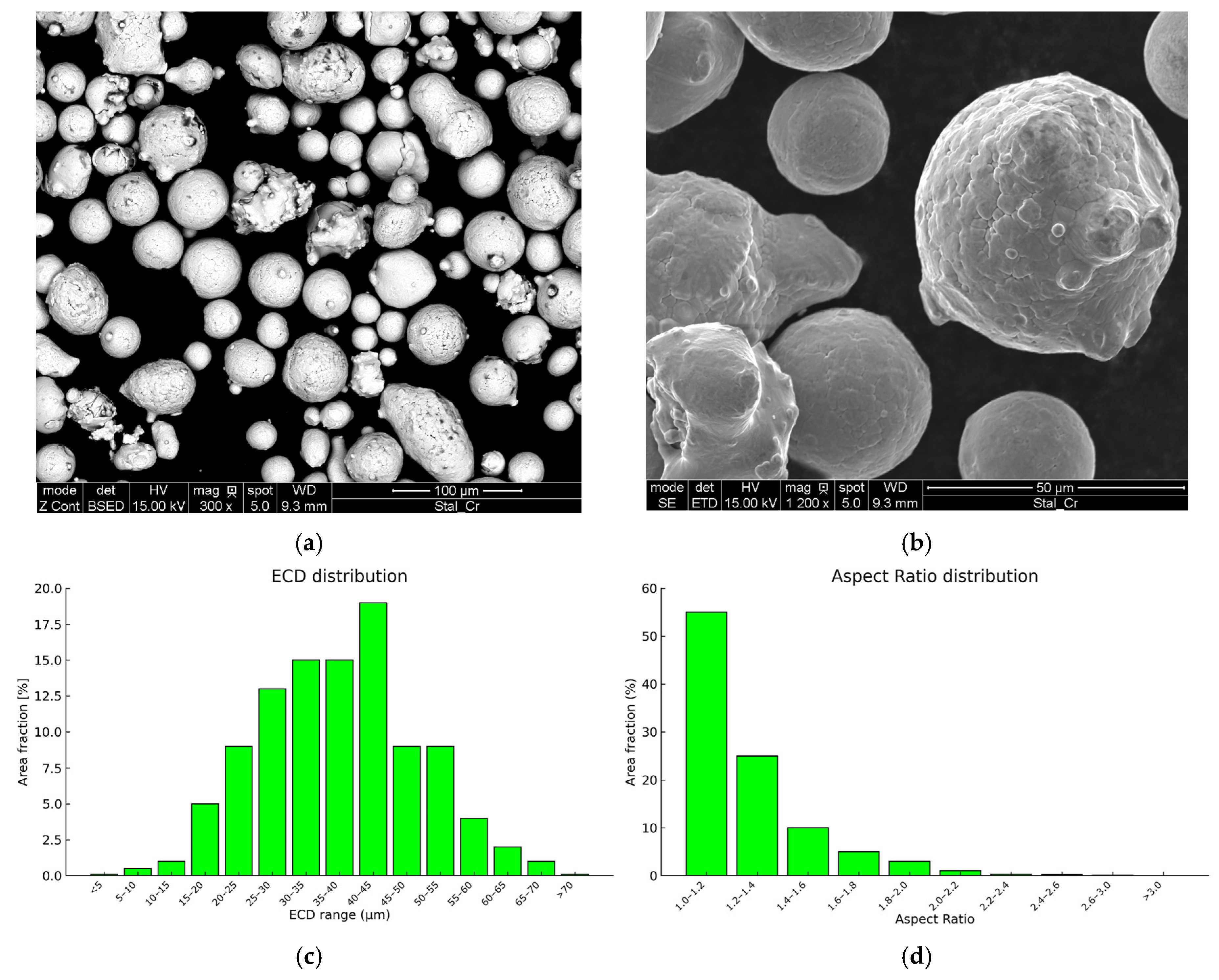

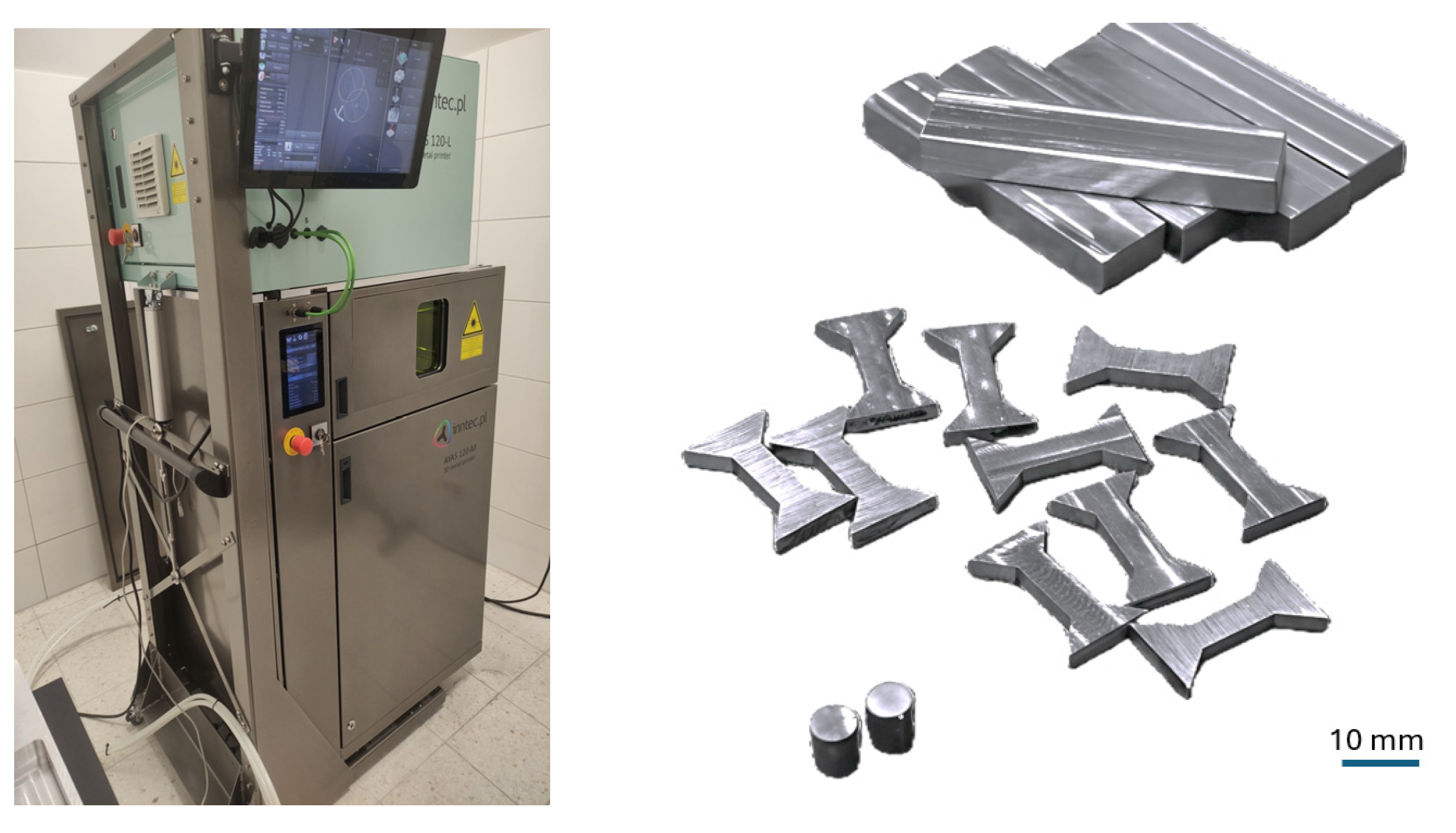

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tested Material

2.2. LPBF Printing Procedure

- —laser power [W];

- —scanning speed [mm/s];

- —layer thickness [mm];

- —scanning track width [mm].

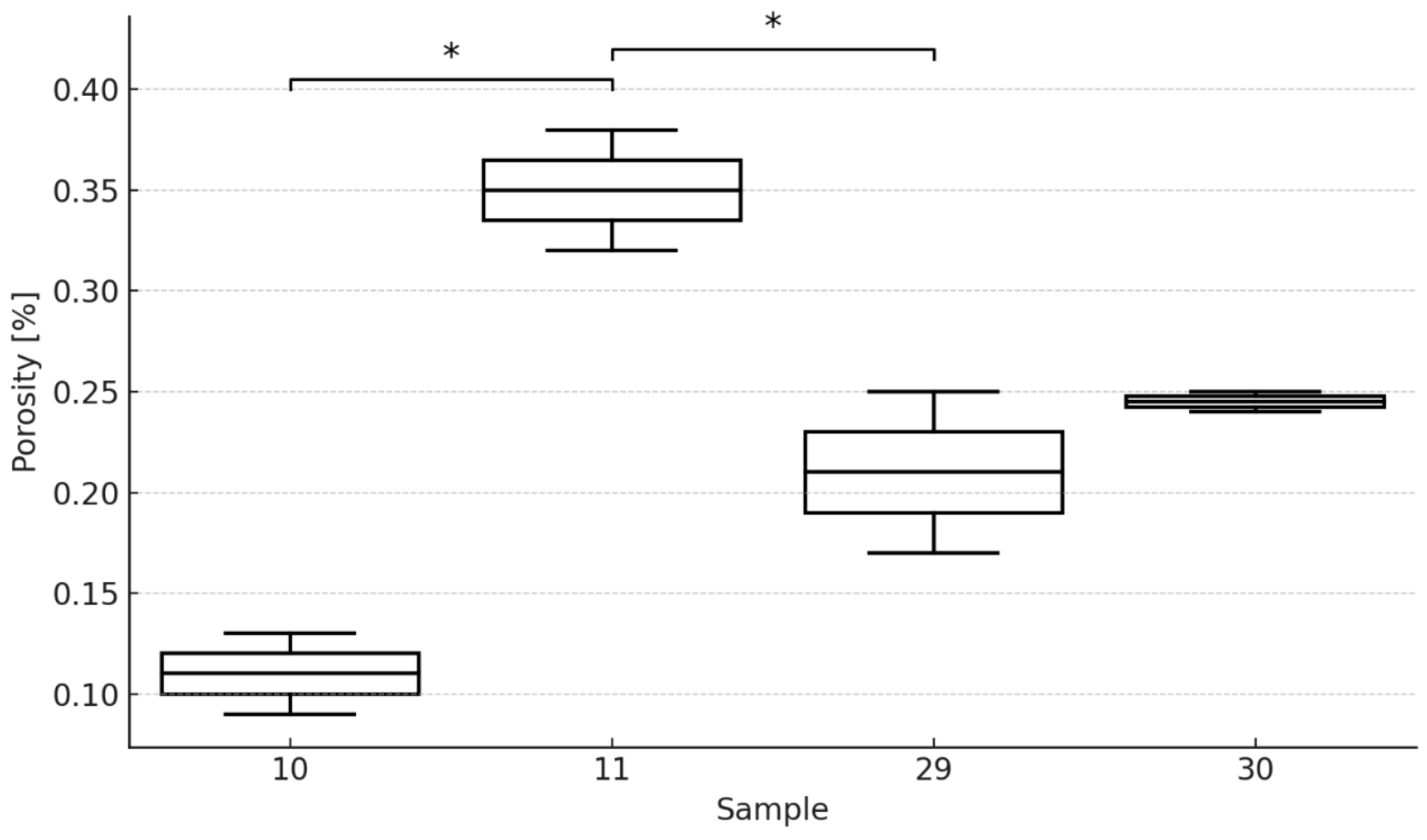

2.3. Quality and Porosity Type

2.4. Hardness Test Procedure

2.5. Tensile Tests Procedure

2.6. Metallographic Tests Procedure

2.7. Strain Test Procedure

2.8. Fracture Strength Test Procedure

- —applied bending force [N];

- —support span [mm];

- —specimen width [mm];

- —specimen height [mm];

- —specimen deflection at the midpoint [mm].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. LPBF Process

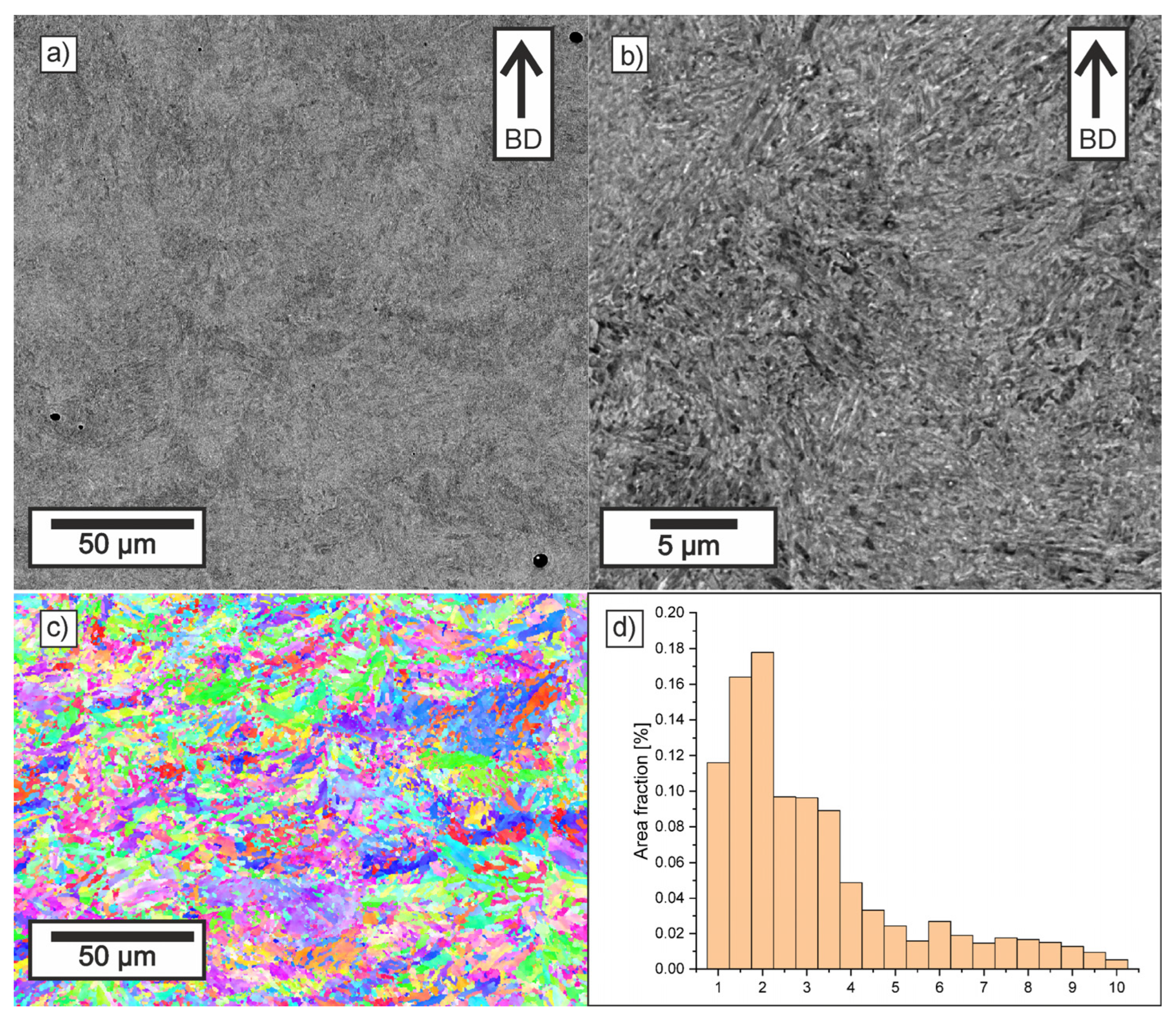

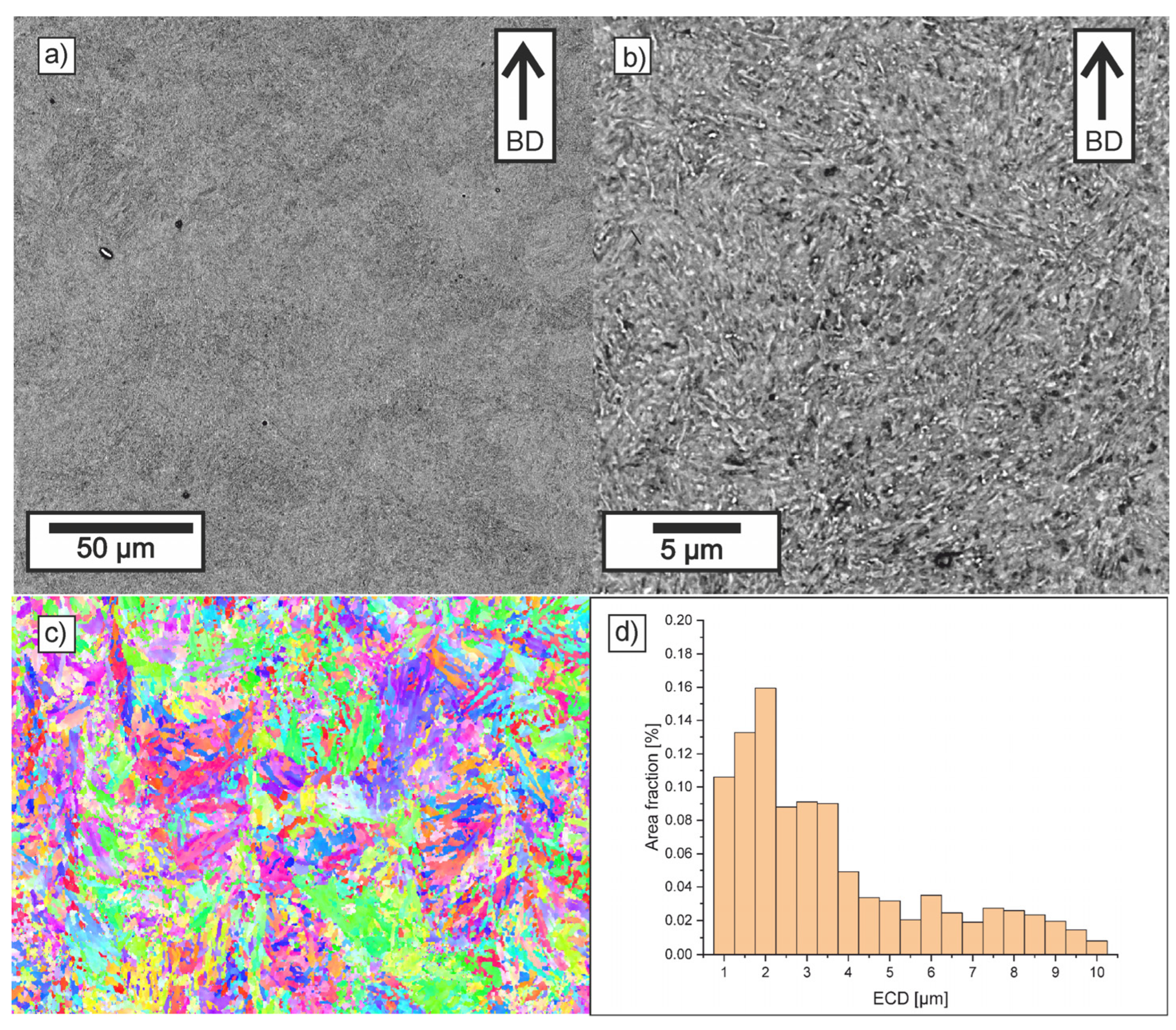

3.2. Microstructure Investigations

3.3. Impact of VED and Printing Orientation on Bending Strength of 3D-Printed 25CrMo4 Steel

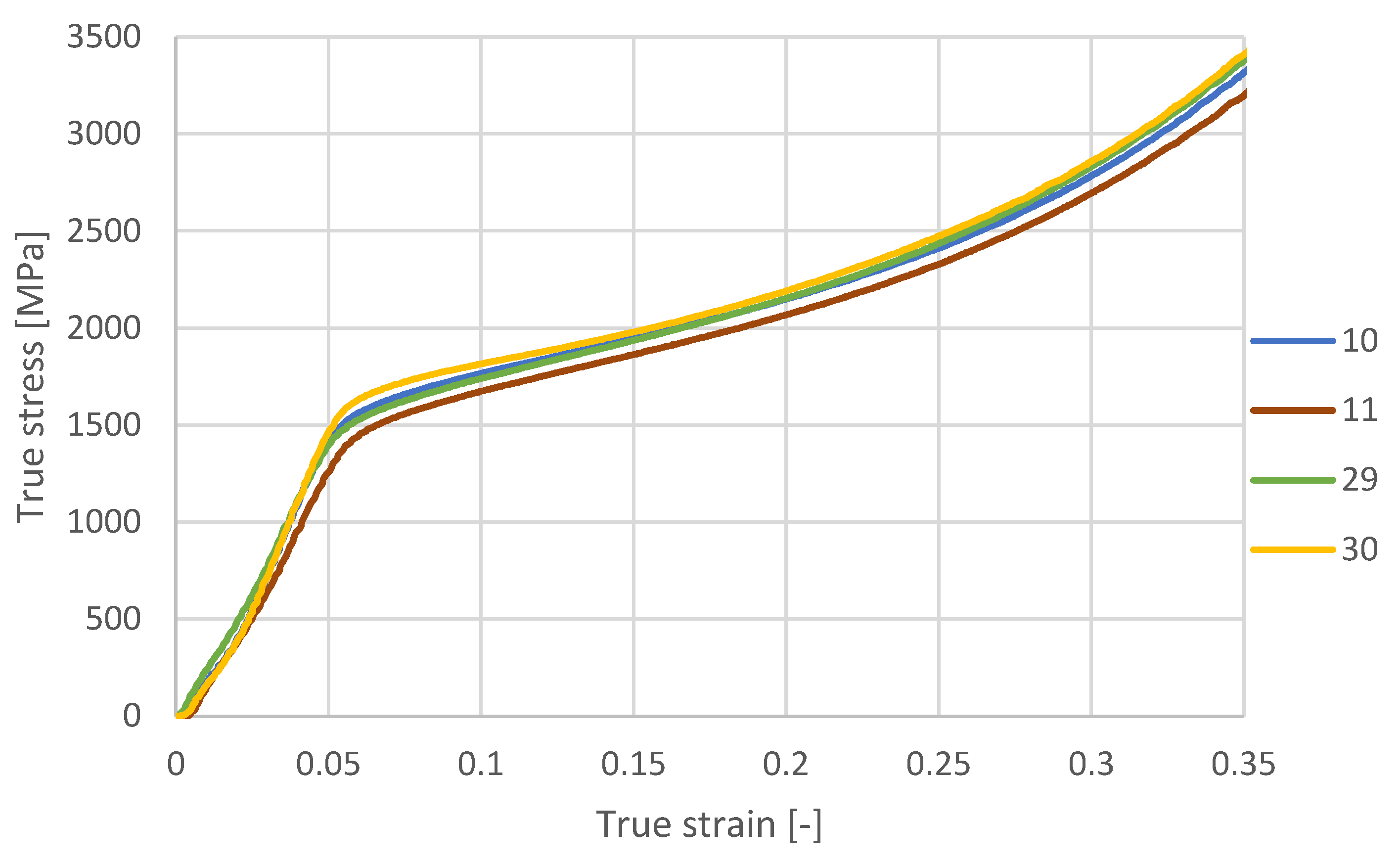

3.4. Mechanical Response of Compressed Samples at Different VED Values

3.5. Hardness Measurements

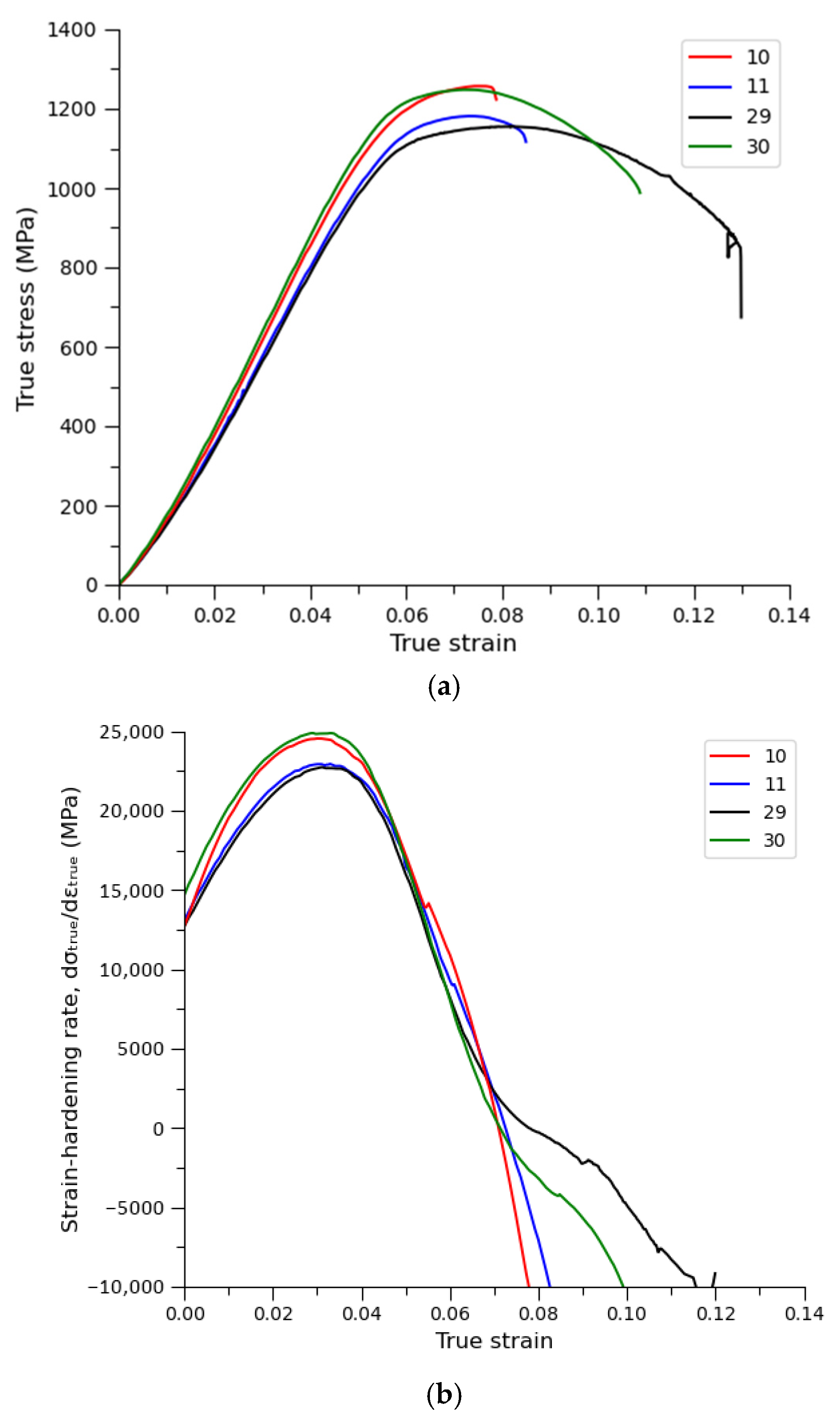

3.6. Stress–Strain Test

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tran, T.Q.; Chinnappan, A.; Lee, J.K.Y.; Loc, N.H.; Tran, L.T.; Wang, G.; Kumar, V.V.; Jayathilaka, W.A.D.M.; Ji, D.; Doddamani, M.; et al. 3D Printing of Highly Pure Copper. Metals 2019, 9, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanke, F.; Hastings, W. Additive Manufacturing Disrupts Automotive Industry. Available online: https://www.automationworld.com/home/blog/13320015/additive-manufacturing-disrupts-automotive-industry (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Sacco, E.; Moon, S.K. Additive Manufacturing for Space: Status and Promises. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 105, 4123–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneck, M.; Horn, M.; Schindler, M.; Seidel, C. Capability of Multi-Material Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion—Development and Analysis of a Prototype Large Bore Engine Component. Metals 2021, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegl, T.; Franke, M.; Raza, A.; Hryha, E.; Körner, C. Effect of AlSi10Mg0.4 Long-Term Reused Powder in PBF-LB/M on the Mechanical Properties. Mater. Des. 2021, 212, 110176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroqueiro, B.; Andrade-Campos, A.; Valente, R.A.F.; Neto, V. Metal Additive Manufacturing Cycle in Aerospace Industry: A Comprehensive Review. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2019, 3, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahazi, M. The Influence of Thermomechanical Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Aisi 4130 Steel. Met. Mater. 1998, 4, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins Freitas, B.J.; Yuuki Koga, G.; Arneitz, S.; Bolfarini, C.; De Traglia Amancio-Filho, S. Optimizing LPBF-Parameters by Box-Behnken Design for Printing Crack-Free and Dense High-Boron Alloyed Stainless Steel Parts. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 2024, 9, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, F.; Rasch, M.; Schmidt, M. Laser Powder Bed Fusion (PBF-LB/M) Process Strategies for In-Situ Alloy Formation with High-Melting Elements. Metals 2021, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhu, Z.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, G.; Lu, Y. Plastic Flow Behavior Based on Thermal Activation and Dynamic Constitutive Equation of 25CrMo4 Steel during Impact Compression. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 707, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.C.; Sheikh, A.A. 3D Printing in Aerospace and Its Long-Term Sustainability. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2015, 10, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasu, S. The Future of 3D Printing in Prototype Development: Minimizing Prototype Costs and Decreasing Validation Timelines. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2023, 5, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabacı, U. The Effects of Oil-Quenching and over-Tempering Heat Treatments on the Dry Sliding Wear Behaviours of 25CrMo4 Steel. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herng, T.S.; Willy, H.J.; Ong, C.Y.A.; Ding, J. Fabrication of 4130 Steel Powder for 3D Printing. In Proceedings of the COMSOL Conference; Department of Materials Science and Engineering, National University of Singapore, Singapore, 22 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Toenjes, A.; Schmidt, J.; Hesselmann, M. Processability of Water Atomized 410L Steel with Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 6343–6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daram, P.; Kusano, M.; Watanabe, M. Investigation of the Process Optimization for L-PBF Hastelloy X Alloy on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, W.; Steinlechner, R.; Hryha, E. Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion of Non-Weldable Low-Alloy Steels. Powder Metall. 2022, 65, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahed, M.; Bengtsson, S.; Boniardi, M.; Casaroli, A.; Casati, R.; Vedani, M. An Investigation on the Plane-Strain Fracture Toughness of a Water Atomized 4130 Low-Alloy Steel Processed by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 855, 143941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Karadge, M.; Rebak, R.B.; Gupta, V.K.; Prorok, B.C.; Lou, X. The Origin and Formation of Oxygen Inclusions in Austenitic Stainless Steels Manufactured by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 35, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridar, S.; Zhao, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, X.; Xiong, W. Post-Heat Treatment Design for High-Strength Low-Alloy Steels Processed by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 788, 139531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tan, Y.H.; Willy, H.J.; Wang, P.; Lu, W.; Cagirici, M.; Ong, C.Y.A.; Herng, T.S.; Wei, J.; Ding, J. Heterogeneously Tempered Martensitic High Strength Steel by Selective Laser Melting and Its Micro-Lattice: Processing, Microstructure, Superior Performance and Mechanisms. Mater. Des. 2019, 178, 107881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, W. Development of Structural Steels for Powder Bed Fusion—Laser Beam. Ph.D. Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fedina, T. Laser Beam–Material Interaction in Powder Bed Fusion. Ph.D. Thesis, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Lu, Z.; Cao, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Cao, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, X. Synergistic Enhancement of Mechanical Strength and Thermal Conductivity in a Novel Al-Mg-Si-Zr-Ce Alloy Fabricated by Powder Bed Fusion-Laser Beam. Mater. Des. 2025, 256, 114305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluczyński, J.; Śnieżek, L.; Grzelak, K.; Janiszewski, J.; Płatek, P.; Torzewski, J.; Szachogłuchowicz, I.; Gocman, K. Influence of Selective Laser Melting Technological Parameters on the Mechanical Properties of Additively Manufactured Elements Using 316L Austenitic Steel. Materials 2020, 13, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M.; Kujawa, M.; Dobrzanski, L.; Tomasz, T. Influence of Technological Parameters on Additive Manufacturing Steel Parts in Selective Laser Sintering. Arch. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 67, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- DebRoy, T.; Wei, H.L.; Zuback, J.S.; Mukherjee, T.; Elmer, J.W.; Milewski, J.O.; Beese, A.M.; Wilson-Heid, A.; De, A.; Zhang, W. Additive Manufacturing of Metallic Components—Process, Structure and Properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 92, 112–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, P.; Hariharan, A.; Kini, A.; Kürnsteiner, P.; Raabe, D.; Jägle, E.A. Steels in Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Their Microstructure and Properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 772, 138633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mu, M.; Yan, J.; Han, B.; Ye, R.; Guo, G. 3D Printing Materials and 3D Printed Surgical Devices in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery: Design, Workflow and Effectiveness. Regen. Biomater. 2024, 11, rbae066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, G.; Liu, Q.; Yao, B.; Liu, H. Review on Preparation Technology and Properties of Spherical Powders. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 1053–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, N.; Ioana, A.; Caloian, V.; Rucai, V.; Dobrescu, C.; Istrate, A.; Pasare, V. Experimental Research for the Establishment of the Optimal Forging and Heat Treatment Technical Parameters for Special Purpose Forged Semi-Finishes. Materials 2023, 16, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouf, S.; Raina, A.; Ul Haq, M.I.; Naveed, N.; Jeganmohan, S.; Kichloo, A. 3D Printed Parts and Mechanical Properties: Influencing Parameters, Sustainability Aspects, Global Market Scenario, Challenges and Applications. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2022, 5, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamhari, F.I.; Foudzi, F.M.; Buhairi, M.A.; Sulong, A.B.; Mohd Radzuan, N.A.; Muhamad, N.; Mohamed, I.F.; Jamadon, N.H.; Tan, K.S. Influence of Heat Treatment Parameters on Microstructure and Mechanical Performance of Titanium Alloy in LPBF: A Brief Review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 4091–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Obeidi, M.; Ahad, I.; Brabazon, D. Investigating the Melt-Pool Temperature Evolution in Laser-Powder Bed Fusion by Means of Infra-Red Light: A Review. Key Eng. Mater. 2022, 926, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhairi, M.; Foudzi, F.; Jamhari, F.; Bakar, A.; Mohd Radzuan, N.; Muhamad, N.; Mohamed, I.F.; Azman, A.H.; Wan Harun, W.S.; Al-Furjan, M. Review on Volumetric Energy Density: Influence on Morphology and Mechanical Properties of Ti6Al4V Manufactured via Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 8, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobel, A.; Hector, L.G.; Chelladurai, I.; Sachdev, A.K.; Brown, T.; Poling, W.A.; Kubic, R.; Gould, B.; Zhao, C.; Parab, N.; et al. In Situ Synchrotron X-Ray Imaging of 4140 Steel Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Materialia 2019, 6, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmueller, S.; Gerhold, L.; Fuchs, L.; Kaserer, L.; Leichtfried, G. Systematic Approach to Process Parameter Optimization for Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Low-Alloy Steel Based on Melting Modes. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 4385–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan Saghaian, S.; Nematollahi, M.; Toker, G.; Hinojos, A.; Shayesteh Moghaddam, N.; Saedi, S.; Lu, C.Y.; Javad Mahtabi, M.; Mills, M.J.; Elahinia, M.; et al. Effect of Hatch Spacing and Laser Power on Microstructure, Texture, and Thermomechanical Properties of Laser Powder Bed Fusion (L-PBF) Additively Manufactured NiTi. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 149, 107680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ning, J.; Liang, S.Y. Analytical Prediction of Balling, Lack-of-Fusion and Keyholing Thresholds in Powder Bed Fusion. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 12053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Chou, K. Formation of Keyhole and Lack of Fusion Pores during the Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process. Manuf. Lett. 2022, 32, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidinia, M.; Sadek, A.; Wang, W.; Kelly, S. Additive Manufacturing of Steel Alloys Using Laser Powder-Bed Fusion. AMP Tech. Artic. 2015, 173, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channa Reddy, S.K.R. Laser Powder Bed Fusion of H13 Tool Steel: Experiments, Process Optimization and Microstructural Characterization. Master’s Thesis, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Tian, T.; Zhang, J.; Niu, L.; Zhu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q. Hot Deformation Behavior of the 25CrMo4 Steel Using a Modified Arrhenius Model. Materials 2022, 15, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 6892-1:2019; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing. Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Wilkinson, A.J.; Britton, T.B. Strains, Planes, and EBSD in Materials Science. Mater. Today 2012, 15, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, D.J.; Barbosa, M.R.; Santos, A.D.; Amaral, R.L.; de Sa, J.C.; Fernandes, J.V. Recurrent Neural Networks and Three-Point Bending Test on the Identification of Material Hardening Parameters. Metals 2024, 14, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Hou, W.; Xing, J.; Sang, L. Numerical and Experimental Investigation of Flexural Properties and Damage Behavior of CFRTP/Al Laminates with Different Stacking Sequence. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatti, V.S.; Saiyathibrahim, A.; Murali Krishnan, R.; Jatti, A.V.; Suganya Priyadharshini, G.; Mohan, D.G. Investigating the Effect of Volumetric Energy Density on Tensile Characteristics of As-Built and Heat-Treated AlSi10Mg Alloy Fabricated by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27, 2401924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simson, T.; Koch, J.; Rosenthal, J.; Kepka, M.; Zetek, M.; Zetková, I.; Wolf, G.; Tomčík, P.; Kulhanek, J. Mechanical Properties of 18Ni-300 Maraging Steel Manufactured by LPBF. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2019, 17, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, A. Effects of Process Parameters on Porosity in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Revealed by X-Ray Tomography. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 30, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, D.; Ledwig, P.; Pasiowiec, H.; Cichocki, K.; Jasiołek, M.; Libura, M.; Pyzalski, M. The Role of Process Parameters in Shaping the Microstructure and Porosity of Metallic Components Manufactured by Additive Technology. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J.S.; Rosenthal, I. Understanding Anisotropic Tensile Properties of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Metals: A Detailed Review of Select Examples; NIST AMS 100-44; National Institute of Standards and Technology (U.S.): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2021; pp. 1–24.

- Cacace, S.; Pagani, L.; Colosimo, B.M.; Semeraro, Q. The Effect of Energy Density and Porosity Structure on Tensile Properties of 316L Stainless Steel Produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 7, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.E.; Barth, H.D.; Castillo, V.M.; Gallegos, G.F.; Gibbs, J.W.; Hahn, D.E.; Kamath, C.; Rubenchik, A.M. Observation of Keyhole-Mode Laser Melting in Laser Powder-Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2014, 214, 2915–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledwig, P.; Pasiowiec, H.; Truczka, B.; Falkus, J. Impact of Chemical Composition Changes during Ultrasound Atomization and Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Low Alloy Steel. Steel Res. Int. 2025, 96, 2400257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Zhao, M.; Luo, X. Study on Typical Defects and Cracking Characteristics of Tool Steel Fabricated by Laser 3D Printing. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 714, 032026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deirmina, F.; Matilainen, V.-P.; Lövquist, S. Hybrid Tool Holder by Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Dissimilar Steels: Towards Eliminating Post-Processing Heat Treatment. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narra, S.P.; Rollett, A.D.; Ngo, A.; Scannapieco, D.; Shahabi, M.; Reddy, T.; Pauza, J.; Taylor, H.; Gobert, C.; Diewald, E.; et al. Process Qualification of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Based on Processing-Defect Structure-Fatigue Properties in Ti-6Al-4V. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 311, 117775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Gibson, I.; Rashed, M.G. Challenges and Prospects of 3D Printing in Structural Engineering. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Steel, Space and Composite Structures, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 31 January–2 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ziętala, M.; Durejko, T.; Polański, M.; Kunce, I.; Płociński, T.; Zieliński, W.; Łazińska, M.; Stępniowski, W.; Czujko, T.; Kurzydłowski, K.J.; et al. The Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Corrosion Resistance of 316L Stainless Steel Fabricated Using Laser Engineered Net Shaping. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 677, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, D. Additive Manufacturing of AISI 316L Stainless Steel: A Review. Metals 2023, 13, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.W.; Guraya, T.; Singamneni, S.; Phan, M.A.L. Grain Growth During Keyhole Mode Pulsed Laser Powder Bed Fusion of IN738LC. JOM 2020, 72, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Zou, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Chen, Q.; Wen, W.; Zang, Y. Effects of Volumetric Energy Density on Melting Modes, Printability, Microstructures, and Mechanical Properties of Laser Powder Bed Fusion (L-PBF) Printed Pure Nickel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 909, 146871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrionuevo, G.O.; Ramos-Grez, J.A.; Sánchez-Sánchez, X.; Zapata-Hidalgo, D.; Mullo, J.L.; Puma-Araujo, S.D. Influence of the Processing Parameters on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of 316L Stainless Steel Fabricated by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, J.; Evans, A.; Mishurova, T.; Ulbricht, A.; Sprengel, M.; Serrano-Munoz, I.; Fritsch, T.; Kromm, A.; Kannengießer, T.; Bruno, G. Diffraction-Based Residual Stress Characterization in Laser Additive Manufacturing of Metals. Metals 2021, 11, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.C.; Shiomi, M.; Osakada, K.; Laoui, T. Rapid Manufacturing of Metal Components by Laser Forming. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2006, 46, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Tong, Y.; Liaw, P.K. Additive Manufacturing of High-Entropy Alloys: A Review. Entropy 2018, 20, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-K.; Kwon, M.-H.; De Cooman, B.C. On the Deformation Twinning Mechanisms in Twinning-Induced Plasticity Steel. Acta Mater. 2017, 141, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabi, M.; Keller, D.; Lüthi, C.; Bambach, M.; Wegener, K. Effect of Process Parameters on Melt Pool Geometry in Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Metals: A Numerical Investigation. Procedia CIRP 2022, 113, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadammal, N.; Cabeza, S.; Mishurova, T.; Thiede, T.; Kromm, A.; Seyfert, C.; Farahbod, L.; Haberland, C.; Schneider, J.A.; Portella, P.D.; et al. Effect of Hatch Length on the Development of Microstructure, Texture and Residual Stresses in Selective Laser Melted Superalloy Inconel 718. Mater. Des. 2017, 134, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Percentage Composition [%] |

|---|---|

| Cr | 0.70–1.20 |

| Mn | 0.30–0.70 |

| Mo | 0.10–0.40 |

| Si | 0.20–0.50 |

| C | 0.27–0.34 |

| P | ≤0.03 |

| S | ≤0.04 |

| Fe | Balance |

| No. | Laser Power [W] | Scanning Speed [mm/s] | Hatch Distance [mm] | Layer Thickness [mm] | LED [J/mm] | VED [J/mm3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 90 | 800 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.112 | 53.6 |

| 2 | 90 | 1000 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.090 | 42.9 |

| 3 | 90 | 1200 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.075 | 35.7 |

| 4 | 110 | 800 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.137 | 65.5 |

| 5 | 110 | 1000 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.110 | 52.4 |

| 6 | 110 | 1200 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.092 | 43.6 |

| 7 | 130 | 800 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.162 | 77.4 |

| 8 | 130 | 1000 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.130 | 61.9 |

| 9 | 130 | 1200 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.108 | 51.6 |

| 10 | 150 | 800 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.187 | 89.3 |

| 11 | 150 | 1000 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.150 | 71.4 |

| 12 | 150 | 1200 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 59.5 |

| 13 | 170 | 800 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.212 | 101.2 |

| 14 | 170 | 1000 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.170 | 80.9 |

| 15 | 170 | 1200 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.142 | 67.5 |

| 16 | 100 | 800 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 46.3 |

| 17 | 100 | 1000 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.100 | 37.0 |

| 18 | 100 | 1200 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.083 | 30.9 |

| 19 | 120 | 800 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.150 | 55.6 |

| 20 | 120 | 1000 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.120 | 44.4 |

| 21 | 120 | 1200 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.100 | 37.0 |

| 22 | 140 | 800 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.175 | 64.8 |

| 23 | 140 | 1000 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.140 | 51.8 |

| 24 | 140 | 1200 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.117 | 43.2 |

| 25 | 160 | 800 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.200 | 74.1 |

| 26 | 160 | 1000 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.160 | 59.3 |

| 27 | 160 | 1200 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.133 | 49.4 |

| 28 | 180 | 800 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.225 | 83.3 |

| 29 | 180 | 1000 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.180 | 66.7 |

| 30 | 180 | 1200 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.150 | 55.6 |

| Laser Power [W] | Laser Scanning Speed [mm/s] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 800 | 1000 | 1200 | |

| 90 | 1 (lack of fusion) | 2 (lack of fusion) | 3 (lack of fusion) |

| 110 | 4 (process window) | 5 (lack of fusion) | 6 (lack of fusion) |

| 130 | 7 (process window) | 8 (slight lack of fusion) | 9 (small lack of fusion) |

| 150 | 10 (small keyhole) | 11 (process window) | 12 (slight lack of fusion) |

| 170 | 13 (keyhole) | 14 (small keyhole) | 15 (process window) |

| Laser Power [W] | Laser Scanning Speed [mm/s] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 800 | 1000 | 1200 | |

| 100 | 16 (lack of fusion) | 17 (lack of fusion) | 18 (lack of fusion) |

| 120 | 19 (slight lack of fusion) | 20 (lack of fusion) | 21 (lack of fusion) |

| 140 | 22 (process window) | 23 (slight lack of fusion) | 24 (slight lack of fusion) |

| 160 | 25 (small keyhole) | 26 (process window) | 27 (slight lack of fusion) |

| 180 | 28 (small keyhole) | 29 (small keyhole) | 30 (process window) |

| Measurement | Sample 10 | Sample 11 | Sample 29 | Sample 30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average porosity, % | 0.11 | 0.35 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| Sample | Bending Strength [MPa] | LED [J/mm] | VED [J/mm3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 2587.8 | 0.18 | 89.3 |

| 11 | 2878.6 | 0.15 | 71.4 |

| 29 | 4004.6 | 0.18 | 66.7 |

| 30 | 3285.4 | 0.15 | 55.6 |

| Sample | Hardness Range [HV1] | Coefficient of Variation [CV] [%] | Average Hardness [HV1] | Standard Deviation [HV1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 456–476 | 1.7 | 467 | 8 |

| 11 | 427–464 | 3.6 | 442 | 16 |

| 29 | 430–474 | 3.3 | 447 | 15 |

| 30 | 408–506 | 6.4 | 466 | 30 |

| Sample | Yield Strength [MPa] | Necking [MPa] | Average UTS [MPa] | Standard Deviation of UTS [MPa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 993 | 1250 | 1342.7 | 27.8 |

| 11 | 928 | 1250 | 1297.7 | 30.3 |

| 29 | 911 | 1142 | 1248.2 | 33.9 |

| 30 | 967 | 1181 | 1324.9 | 38.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kublińska, A.; Dzienniak, D.; Sułowski, M.; Cieślik, J.; Ledwig, P.; Cichocki, K.; Lisiecka-Graca, P.; Bembenek, M. Laser Powder Bed Fusion of 25CrMo4 Steel: Effect of Process Parameters on Metallurgical and Mechanical Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 5390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235390

Kublińska A, Dzienniak D, Sułowski M, Cieślik J, Ledwig P, Cichocki K, Lisiecka-Graca P, Bembenek M. Laser Powder Bed Fusion of 25CrMo4 Steel: Effect of Process Parameters on Metallurgical and Mechanical Properties. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235390

Chicago/Turabian StyleKublińska, Agnieszka, Damian Dzienniak, Maciej Sułowski, Jacek Cieślik, Piotr Ledwig, Kamil Cichocki, Paulina Lisiecka-Graca, and Michał Bembenek. 2025. "Laser Powder Bed Fusion of 25CrMo4 Steel: Effect of Process Parameters on Metallurgical and Mechanical Properties" Materials 18, no. 23: 5390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235390

APA StyleKublińska, A., Dzienniak, D., Sułowski, M., Cieślik, J., Ledwig, P., Cichocki, K., Lisiecka-Graca, P., & Bembenek, M. (2025). Laser Powder Bed Fusion of 25CrMo4 Steel: Effect of Process Parameters on Metallurgical and Mechanical Properties. Materials, 18(23), 5390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235390