Simulation of Residual Stress Around Nano-Perforations in Elastic Media: Insights for Porous Material Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Geometric generalization: The semi-analytical framework is extended from purely polygonal pairs to mixed polygonal–elliptical combinations. The triangular and square approximations represent faceted nano-voids, while the elliptical perforation represents a generic smooth defect, encompassing circular pores and crack-like voids (via its aspect ratio). Such combinations are more representative of realistic pore networks in nanoporous metals and complex composites.

- (2)

- Unified competition mechanism: Through systematic numerical investigations of triangular–elliptical and square–elliptical pairs, the residual stress fields are analyzed with respect to inter-perforation distance and size ratios. It is shown that the stress state can be described by a competition between intrinsic surface tension effects and extrinsic elastic interactions, with a critical distance controlling the transition between a surface-tension-dominated regime and an interaction-dominated regime. This competition mechanism is demonstrated to be robust across different shape combinations, thereby upgrading earlier, shape-specific observations to a general principle.

- (3)

- Design-oriented insights: The numerical results are synthesized into quantitative guidelines for the microstructural design of nanoporous materials. In particular, it is demonstrated that (i) closely spaced perforations lead to severe stress intensification near adjacent vertices, defining likely sites for crack initiation and failure, and (ii) increasing the size of one perforation can, under appropriate configurations, effectively shield a neighboring perforation and reduce the overall stress level. These findings enable a shift from trial-and-error approaches to physics-based, bottom-up design of porous architectures.

2. Theoretical Framework and Solution Method

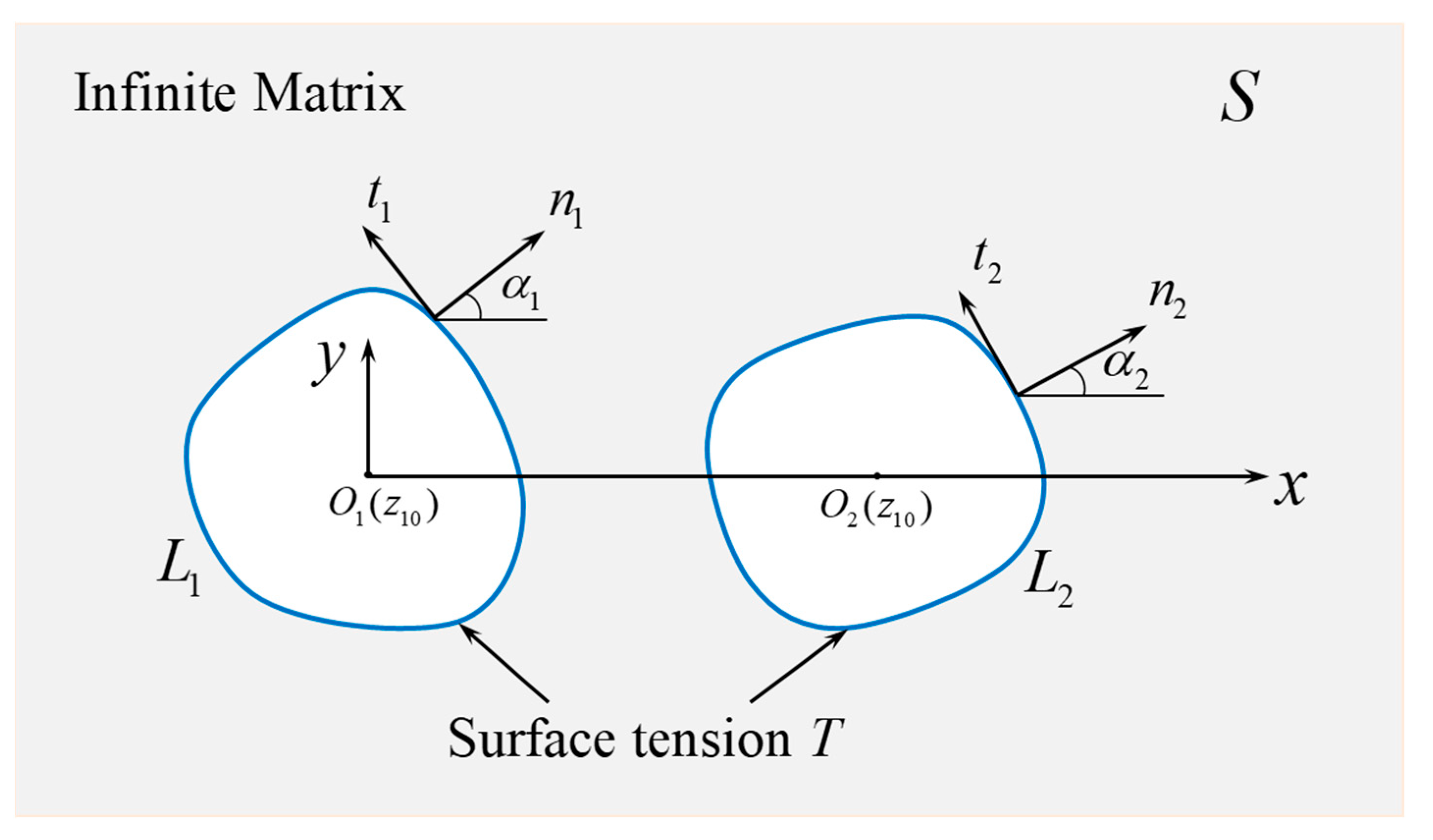

2.1. Problem Statement and Governing Equations

2.2. Conformal Mapping and Solution Procedure

3. Numerical Results

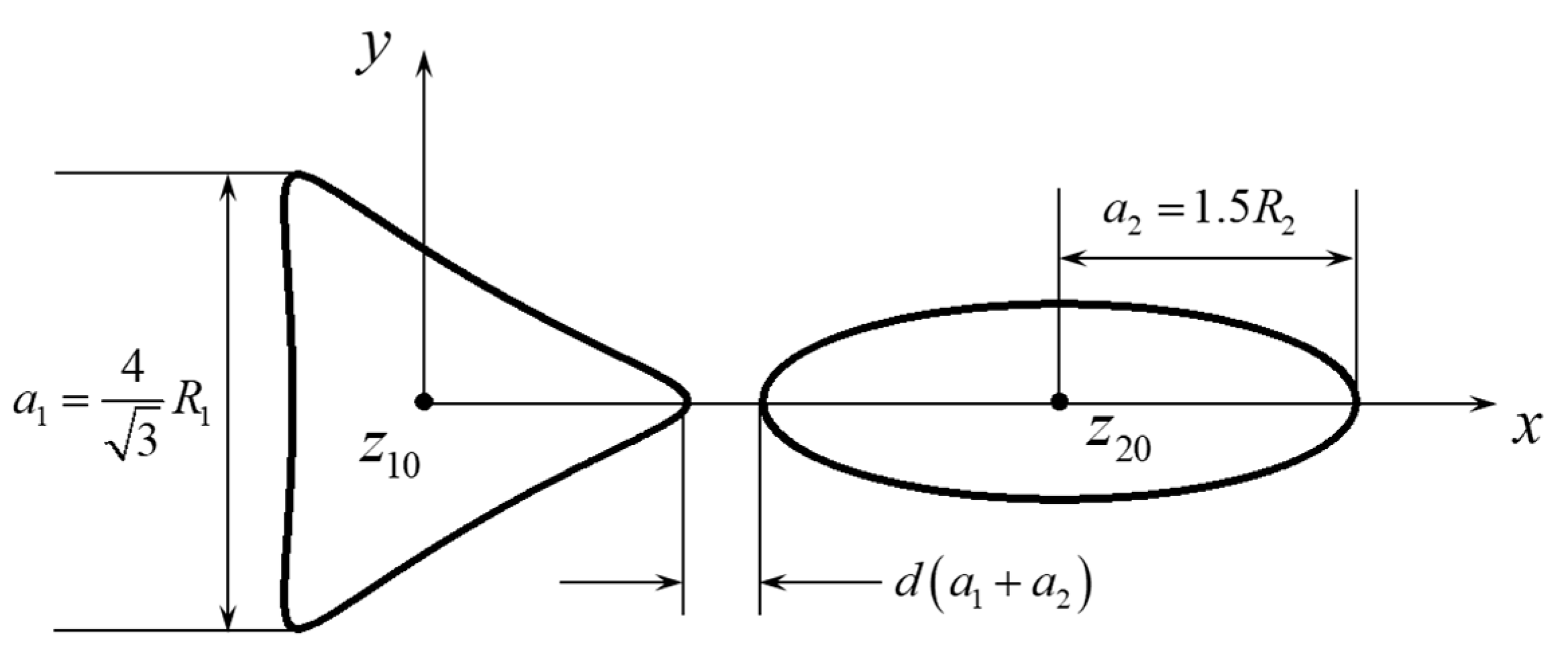

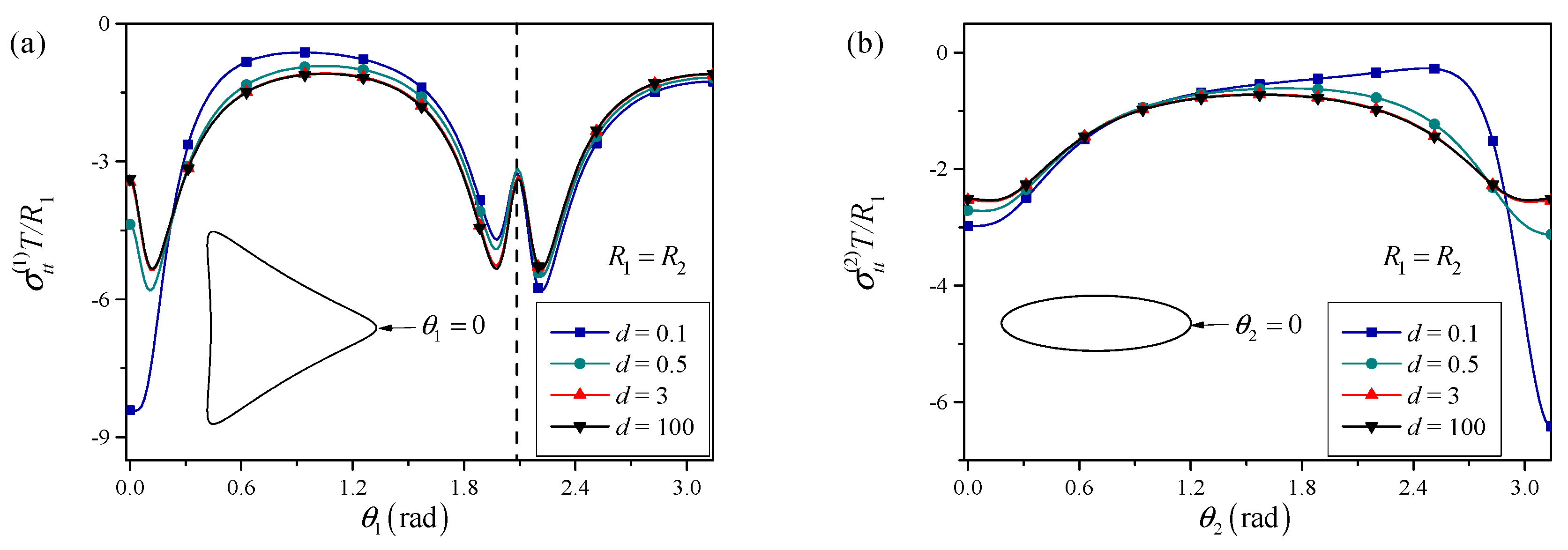

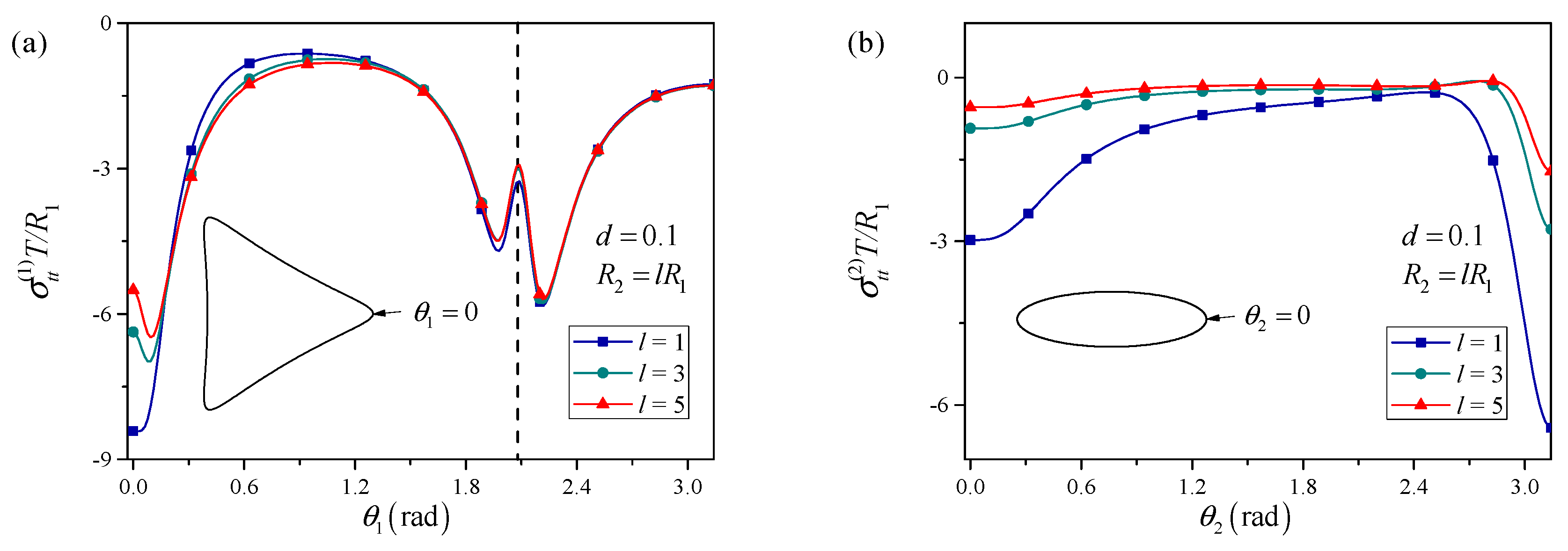

3.1. Interaction Between a Triangular and an Elliptical Perforation

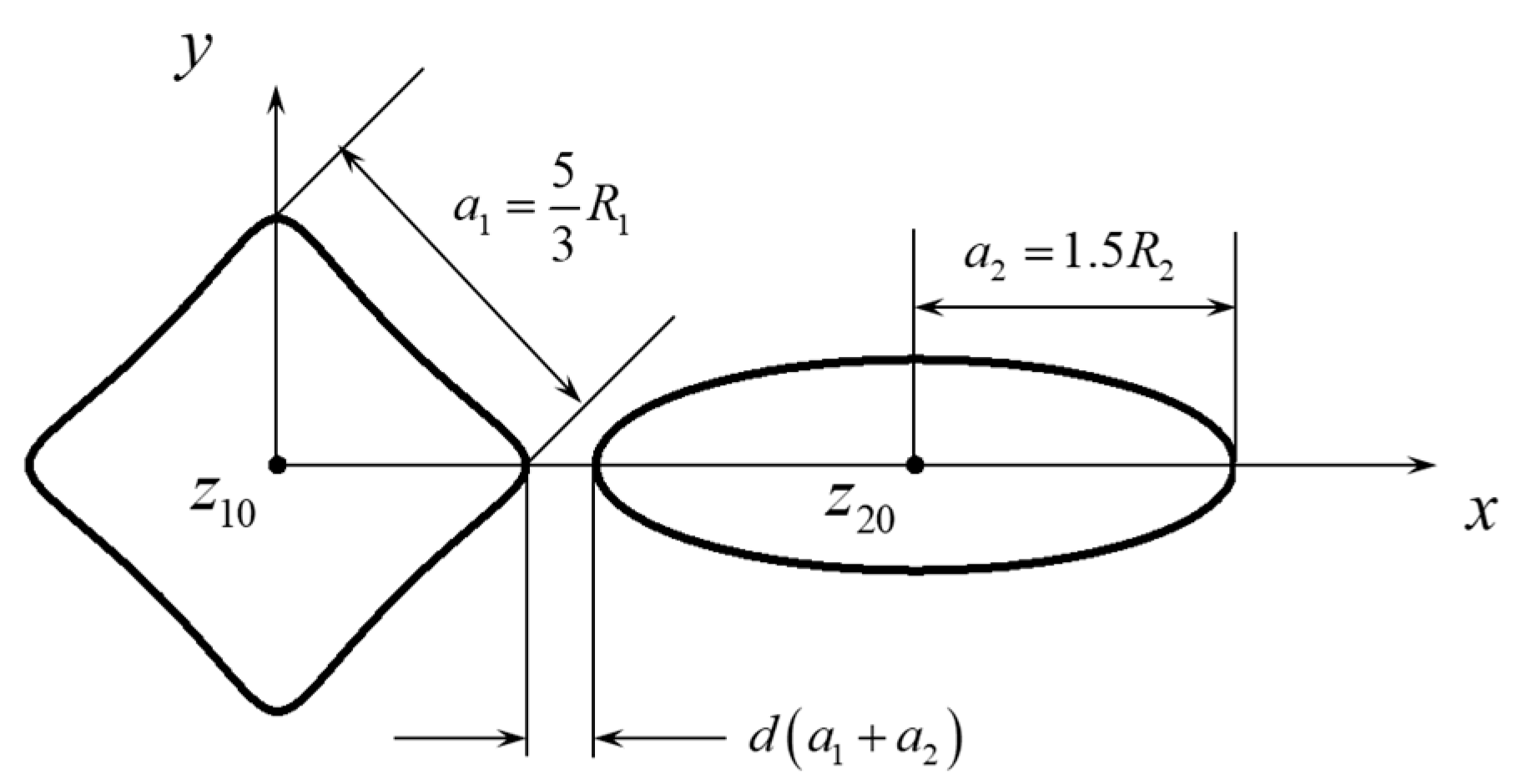

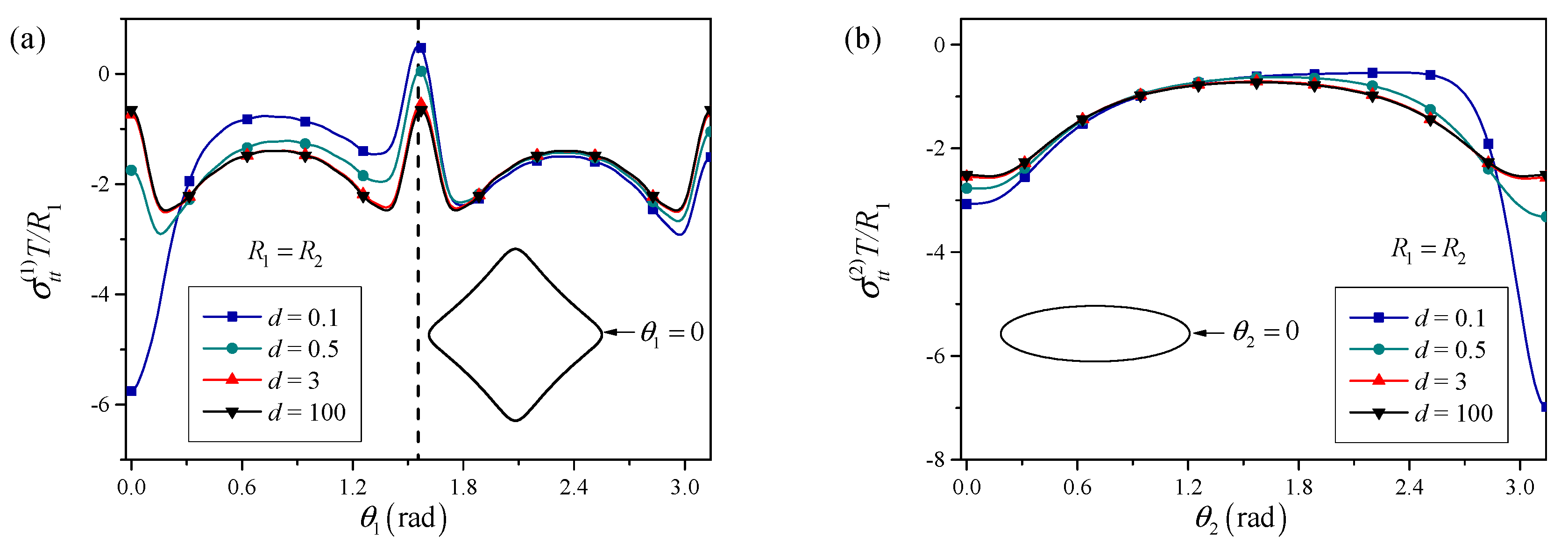

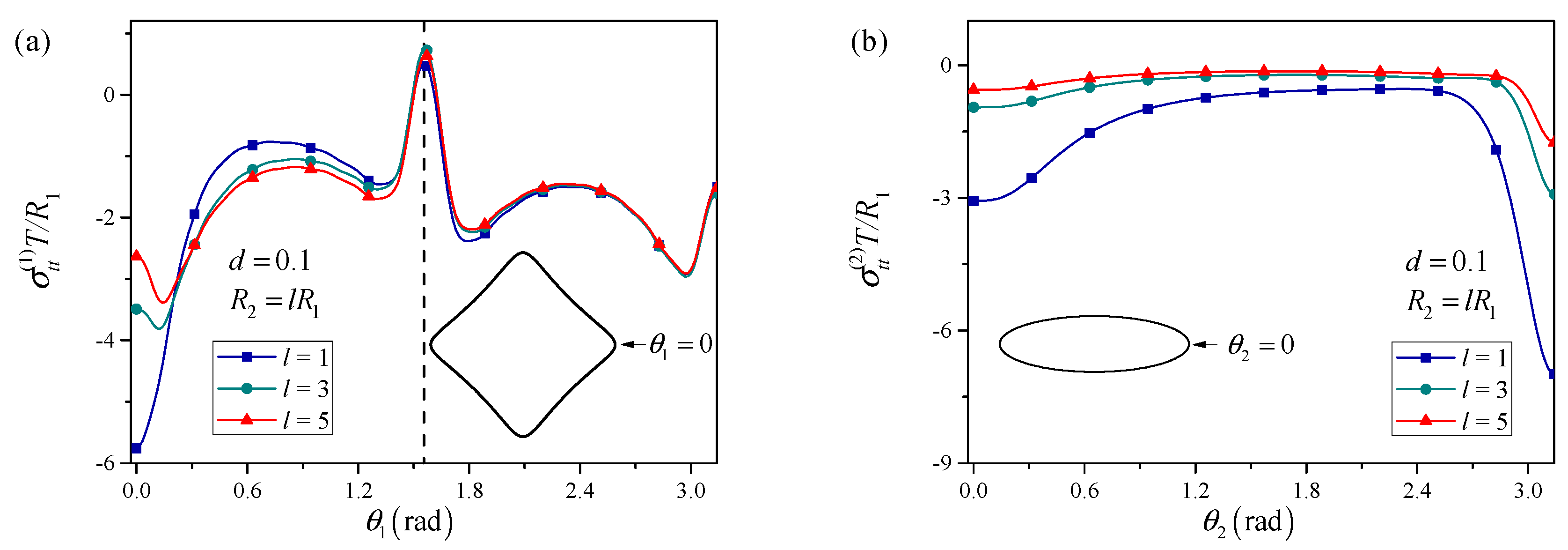

3.2. Interaction Between a Square and an Elliptical Perforation

4. Discussions

4.1. Method Validation and Relation to Previous Works

4.2. Governing Competition Mechanism

- Intrinsic Factor (Surface Tension): This effect scales with the local curvature and is a property of the individual perforation. It dictates the stress distribution when perforations are widely spaced.

- Extrinsic Factor (Perforation Interaction): This effect scales with the inverse of the distance between perforation boundaries and depends on their relative orientation and size. It dictates the stress redistribution when perforations are in close proximity.

4.3. Geometric Motivation and Design Implications

5. Conclusions and Implications for Material Design

- (a)

- Governing competition mechanism: The residual stress field is governed by a competition between intrinsic surface tension effects and extrinsic elastic interactions between perforations. The normalized inter-perforation distance d serves as the control parameter, with a critical threshold of marking the transition from a surface-tension-dominated regime to an interaction-dominated regime.

- (b)

- Geometric proximity is critical and synergistic: The distance between perforations is a primary factor controlling stress concentration. Densely packed perforated structures are prone to severe stress intensification at regions where perforations are in close proximity, defining likely sites for crack initiation and mechanical failure. Our analysis reveals that this is due to a synergistic superposition of stress fields in the inter-perforation ligament, establishing the perforation pair as the critical failure unit.

- (c)

- Size distribution as a design tool and the “shielding effect”: The relative size of adjacent perforations can be leveraged to manage stress. A larger perforation can shield a smaller, adjacent perforation by reducing the stress concentration at the nearby vertex. This is mechanistically explained as the larger perforation’s stress field dominating and beneficially influencing the inter-perforation region.

- (d)

- Universality: The fundamental phenomena of stress intensification with proximity and shielding with size disparity are robust across different shape combinations (triangular/elliptical, square/elliptical). This universality makes these findings widely applicable for the design of various nanoscale porous and perforated materials.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wright, A.M.; Kapelewski, M.T.; Marx, S.; Farha, O.K.; Morris, W. Transitioning metal–organic frameworks from the laboratory to market through applied research. Nat. Mater. 2025, 24, 78–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.H.; Mou, C.Y.; Lin, H.P. Synthesis of mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 3862–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, B.; Tan, F.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, Z. Formation and microstructures of nanoporous gold films with tunable compositions/porosities/sizes through chemical dealloying of dilute solid solution Cu-Au alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, N.; Neuenschwander, M.; Adams, J.D.; Andany, S.H.; Peric, O.; Winhold, M.; Giordano, M.G.; Bhat, V.S.; Penedo, M.; Grundler, D.; et al. A polymer–semiconductor–ceramic cantilever for high-sensitivity fluid-compatible microelectromechanical systems. Nat. Electron. 2024, 7, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, S.; Wang, W.; Lee, H.; Liu, L.; Umrao, S.; Liu, W.; Bacon, A.; Tibbs, J.; Khemtonglang, K.; Tan, A.; et al. Photonic crystal grating resonance and interfaces for health diagnostic technologies. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 6435–6540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Bastos, L.V.; Das, D.; Ambekar, R.S.; Woellner, C.; Pugno, N.M.; Tiwary, C.S. Composite strengthening via stress-concentration regions softening: The proof of concept with Schwarzites and Schwarzynes inspired multi-material additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 90, 104336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, K.H.; Pyo, J.B.; Song, H.; Kim, T.S. Evaluation of stress distribution in carbon-based nanoporous electrode by three-dimensional nanostructural reconstruction. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 41, e01112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtin, M.E.; Murdoch, A.I. A continuum theory of elastic material surfaces. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 1975, 57, 291–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtin, M.E.; Murdoch, A.I. Surface stress in solids. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1978, 14, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtin, M.E.; Weissmuller, J.; Larche, F. A general theory of curved deformable interfaces in solids at equilibrium. Philos. Mag. A 1998, 78, 1093–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dai, M.; Ru, C.Q.; Gao, C.F. Stress field around an arbitrarily shaped nanosized hole with surface tension. Acta Mech. 2014, 225, 3453–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, V.B. Size-dependent rigidities of nanosized torsional elements. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2002, 39, 4039–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Ganti, S. Size-dependent Eshelby’s tensor for embedded nano-inclusions incorporating surface/interface energies. ASME J. Appl. Mech. 2004, 71, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.L.; Wang, J.; Huang, Z.P.; Karihaloo, B.L. Size-dependent effective elastic constants of solids containing nanoinhomogeneities with interface stress. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2005, 53, 1574–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.F.; Wang, T.J. Deformation around a nanosized elliptical hole with surface effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 161901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Wheeler, L.T. Size-dependent elastic state of ellipsoidal nano-inclusions incorporating surface/interface tension. ASME J. Appl. Mech. 2007, 74, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Rajapakse, R.K.N.D. Analytical solution for size-dependent elastic field of a nanoscale circular inhomogeneity. ASME J. Appl. Mech. 2007, 74, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Rajapakse, R.K.N.D. Elastic field of an isotropic matrix with a nanoscale elliptical inhomogeneity. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2007, 44, 7988–8005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Gao, C.F.; Ru, C.Q. Surface tension-induced stress concentration around a nanosized hole of arbitrary shape in an elastic half-plane. Meccanica 2014, 49, 2847–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogilevskaya, S.G.; Crouch, S.L.; Stolarski, H.K. Multiple interacting circular nano-inhomogeneities with surface/interface effects. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2008, 56, 2298–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gao, C.F.; Chen, Z.T. Interaction between two nanoscale elliptical holes with surface tension. Math. Mech. Solids 2019, 24, 1556–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, H.; Gao, C.; Chen, Z. In-plane stress analysis of two nanoscale holes under surface tension. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2020, 90, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskhelishvili, N.I. Some Basic Problems of the Mathematical Theory of Elasticity, 1st ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Huang, C.; Wang, S.; Cai, D. A modified Laurent series for hole/inclusion problems in plane elasticity. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 2021, 72, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Jia, X.; Song, K.; Yang, H.; Xing, S.; Li, H.; Cheng, M. Simulation of Residual Stress Around Nano-Perforations in Elastic Media: Insights for Porous Material Design. Materials 2025, 18, 5388. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235388

Wang S, Jia X, Song K, Yang H, Xing S, Li H, Cheng M. Simulation of Residual Stress Around Nano-Perforations in Elastic Media: Insights for Porous Material Design. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5388. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235388

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shuang, Xin Jia, Kun Song, Haibing Yang, Shichao Xing, Hongyuan Li, and Ming Cheng. 2025. "Simulation of Residual Stress Around Nano-Perforations in Elastic Media: Insights for Porous Material Design" Materials 18, no. 23: 5388. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235388

APA StyleWang, S., Jia, X., Song, K., Yang, H., Xing, S., Li, H., & Cheng, M. (2025). Simulation of Residual Stress Around Nano-Perforations in Elastic Media: Insights for Porous Material Design. Materials, 18(23), 5388. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235388